- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Glenn Hubbard

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Glenn Hubbard

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

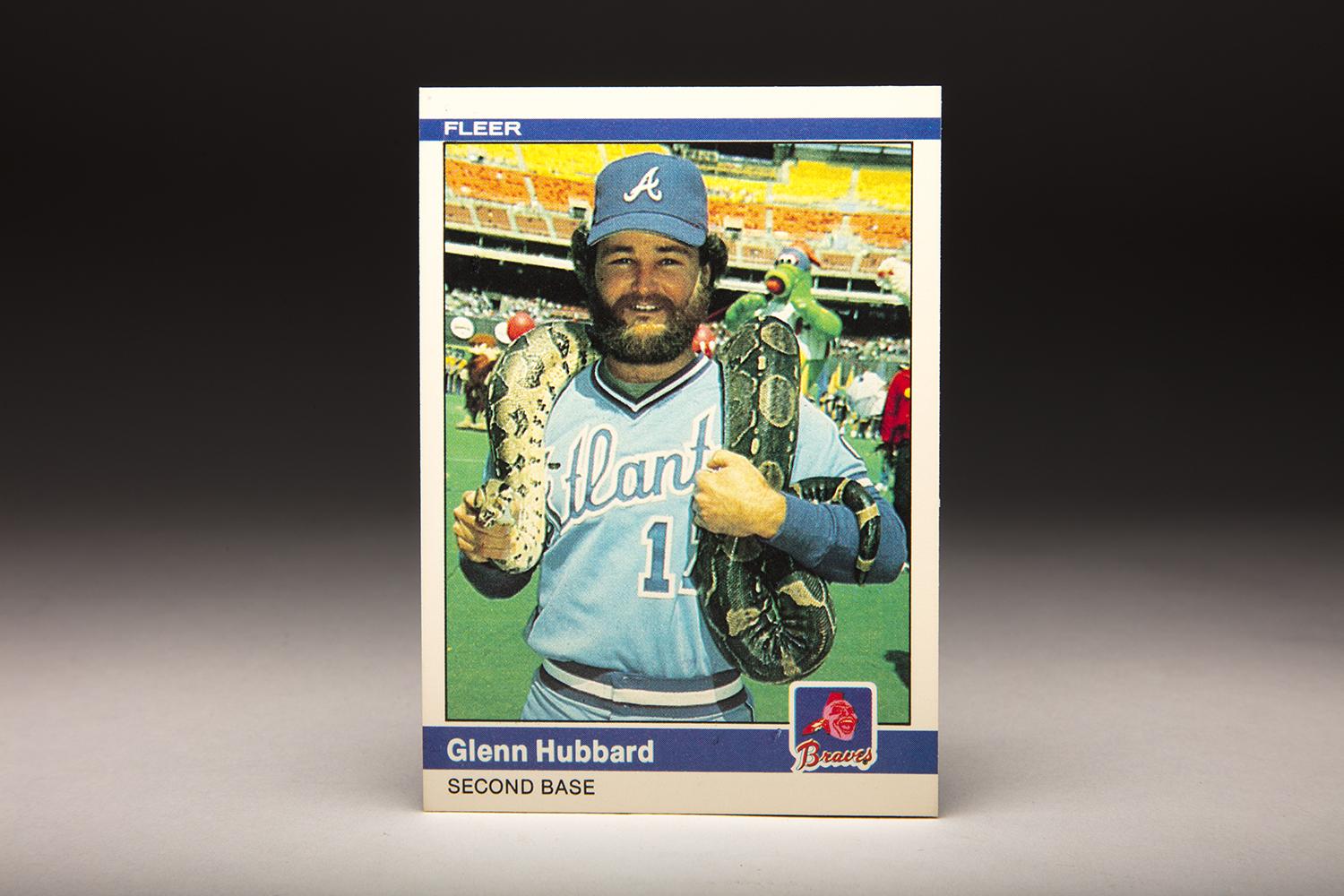

As much as I like to call myself a fan of horror films, I do not have much love for snakes – or films in which snakes are the stars. Films like Anaconda and Snakes on a Plane give me the chills – and not the good kind. In some of these movies, the snakes are so large, or so plentiful, that I become tempted to grab the clicker (or the remote, in more formal parlance) and find the closest sitcom available on our cable system. Beyond that, the slithering motion of the snakes practically brings me to a point of hyperventilation. When it comes to a snakes on a baseball card, I have a different reaction. Perhaps it’s because the snakes are motionless on a still photograph. They also appear much smaller on a two-by-three card than they do on a giant television screen. But their appearance on a card is still just as weird. Why in the world would a snake ever appear on a player’s card? Leave it to the Fleer Company to fill this strange void in card collecting. As the great Rod Serling might have said, “submitted for your approval” is this 1984 Fleer card showcasing Atlanta Braves second baseman Glenn Hubbard. Based on the powder blue road uniform that Hubbard is wearing, we know that this photograph was not taken at Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium. No, it must have been snapped at one of the National League’s other ballparks.

The artificial turf in the background narrows it to Cincinnati, Montreal, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh or St. Louis. A closer look narrows it down far more precisely; the presence of the “Phillie Phanatic” in the background tells us this must be Veterans Stadium, then the home of the Phillies. In addition to the Phillie Phanatic, we have a Barney Rubble mascot (from Flintstones fame), a squadron of colorful balloons, and oh yes, that gigantic snake wrapped around the shoulders of Mr. Hubbard. This was some kind of pre-game promotion that the Phillies staged back in the middle of the 1983 season! Over the years, I’ve become curious as to the kind of snake that Hubbard is holding. I confess to knowing almost nothing about snakes, other than the fact that I don’t like them, and certain members of my family are absolutely terrified by them. I have always assumed that the snake in question is not poisonous, but it is no less frightening to me and small children. After initially writing about this card seven years ago, a faithful reader informed me that the snake in question was indeed a boa constrictor, a large snake with a thick body. The reader assured me that this kind of snake was not poisonous. That’s good to know, but it only slightly lessens my fear of serpents. I later discovered that this particular boa constrictor spanned eight feet in length. That, of course, is disturbing to the say the least. For what it’s worth, the Phillie Phanatic looks particularly alarmed by the presence of the large snake on Hubbard’s shoulders. In contrast, Hubbard looks completely unconcerned. He’s content, almost proud of his serpentine friend. So here’s the relevant question. Why? For years, I tried to research the back story to this card, but came up empty in my searches. Why is Hubbard holding a snake, which has been draped over his shoulders? Why is he holding such a large snake, one that appears capable of strangling him, even though it’s not? And taken a step further, is Hubbard out of his mind? Thankfully, we now have some answers, with credit going to a recent interview that the Carolina Sports Network conducted with Hubbard. No, Hubbard was not out of his mind, even if he did something that many of us would have avoid. Here’s what actually happened. On that day in 1983, when the photograph was taken, the Phillie Phanatic was having a birthday party on the field at Veterans Stadium. To celebrate the madcap affair, the Phillies invited all sorts of costumed characters and strange animals onto the field, which helps explain the presence of the Barney Rubble lookalike and the aforementioned boa constrictor.

“They had a guy with a snake,” Hubbard remembered in his interview with the Carolina Sports Network. “I grabbed the guy and I grabbed the photographer and said, ‘Can I get my picture taken with the snake?’

“So he takes the picture and sends it to me in the mail; it was a big picture, an eight-by-10. The next Spring Training, a kid comes up to me and says, ‘Can you sign this for me?’ It (the photo) had ended up on a baseball card. Well, unbeknownst to me, the photographer was a freelance photographer for Fleer, a (recent) start-up company (with cards), and they just wanted some unique cards. That’s how it came about.”

In retrospect, some 35 years after the fact, Hubbard questions why he did what he did. “When I look at it now, (I say to myself) ‘What was I thinking?’

For a number of years, the snake card became a sore point with Hubbard.

“I used to not sign that thing,” Hubbard said, referring to the card, and not the snake. “I was mad that it ended up on a baseball card. I didn’t realize back then that any photo they take of you on a baseball field can end up the property of Major League Baseball. People would send me that card in the mail, but I would mail them back another card (signed for them). Nowadays, I don’t care. Now I do (sign the snake card).”

In 2016, the Fleer snake card gained new life when Hubbard’s minor league team, the Lexington Legends, produced a bobblehead doll showing Hubbard with the snake wrapped around his shoulders. For Hubbard, a longtime baseball man now serving as the team’s bench coach, the unique promotion seemed like a natural. For his part, Hubbard now has both the card and the bobblehead doll in his personal collection.

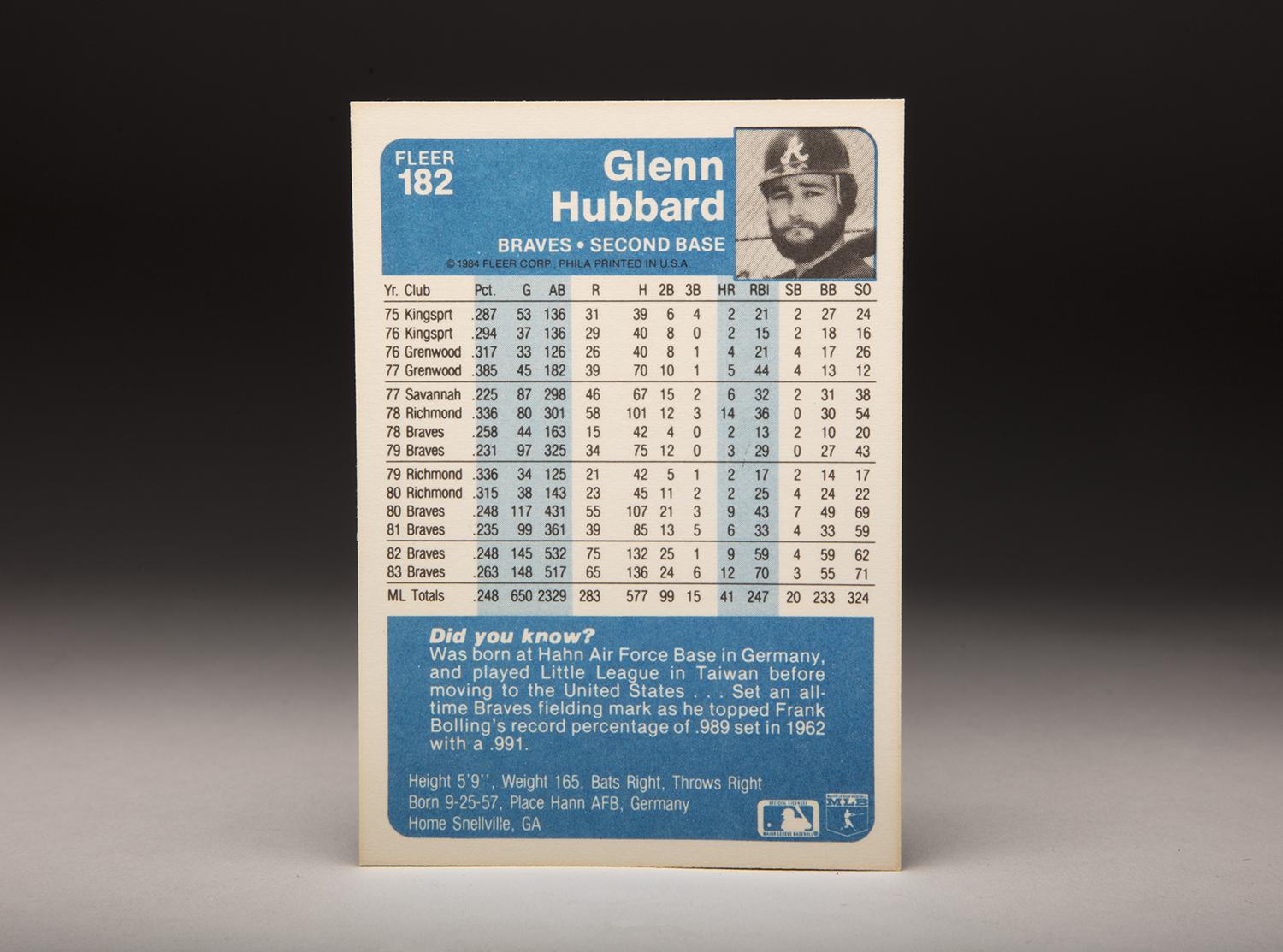

While the Fleer card is what some fans best remember Hubbard for, his professional career actually began eight years earlier, when he was drafted in the 20th round by the Braves. At all of 17 years of age in 1975, Hubbard began his career in the Appalachian League. Only three years later, he debuted for the Braves as a 20-year-old, hitting a respectable .258 in 44 games. The following year, the Braves made him their regular second baseman.

Hubbard established a reputation as a light-hitting but strong-fielding second baseman. He gained a bit of notoriety in 1982 when he led the National League with 20 sacrifice hits, a testament to his superior bunting skills. He gained far more notoriety when ESPN’s Chris Berman began to refer to him as Glenn “Mother” Hubbard on SportsCenter broadcasts. By far Hubbard’s best year occurred in 1983, the same year that he posed with the snake. That season, Hubbard hit .263 with 12 home runs and 55 walks, qualifying for the All-Star team for the first and only time in his career. The snake charm wore off somewhat in 1984, but Hubbard remained the Braves’ second baseman through the 1987 season. Becoming a free agent that winter, he signed with the Oakland A’s, who were on the verge of dominating the American League. Hubbard became Oakland’s starting second baseman in 1988 before being demoted to a utility role in 1989. He played in the 1988 World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers, but was released in midsummer of ’89, denying him a chance to play for an A’s team that would go on to win the world championship. Although Hubbard was still only 31 years old, he didn’t find any takers. Given his intelligence and work ethic, Hubbard made the natural move into coaching. For the next 22 years, he served the Braves’ organization, first as a minor league coach and then as first base coach in Atlanta. When Bobby Cox retired as manager in 2010, the Braves let Hubbard go, but he didn’t remain out of work for long. In fact, that very day the Kansas City Royals called him with a job offer. He’s been with the Royals ever since, continuing his work as a coach with minor league Lexington. Remarkably, Hubbard has worked in baseball – as a player and coach – for 42 consecutive seasons. It has been a remarkable career for this baseball lifer, even if too many people want to ask him about that 1984 Fleer card and the eight-foot snake. But Hubbard handles the snake questions with grace and patience, just like he handled the snake itself with such deftness so many years ago.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital & outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

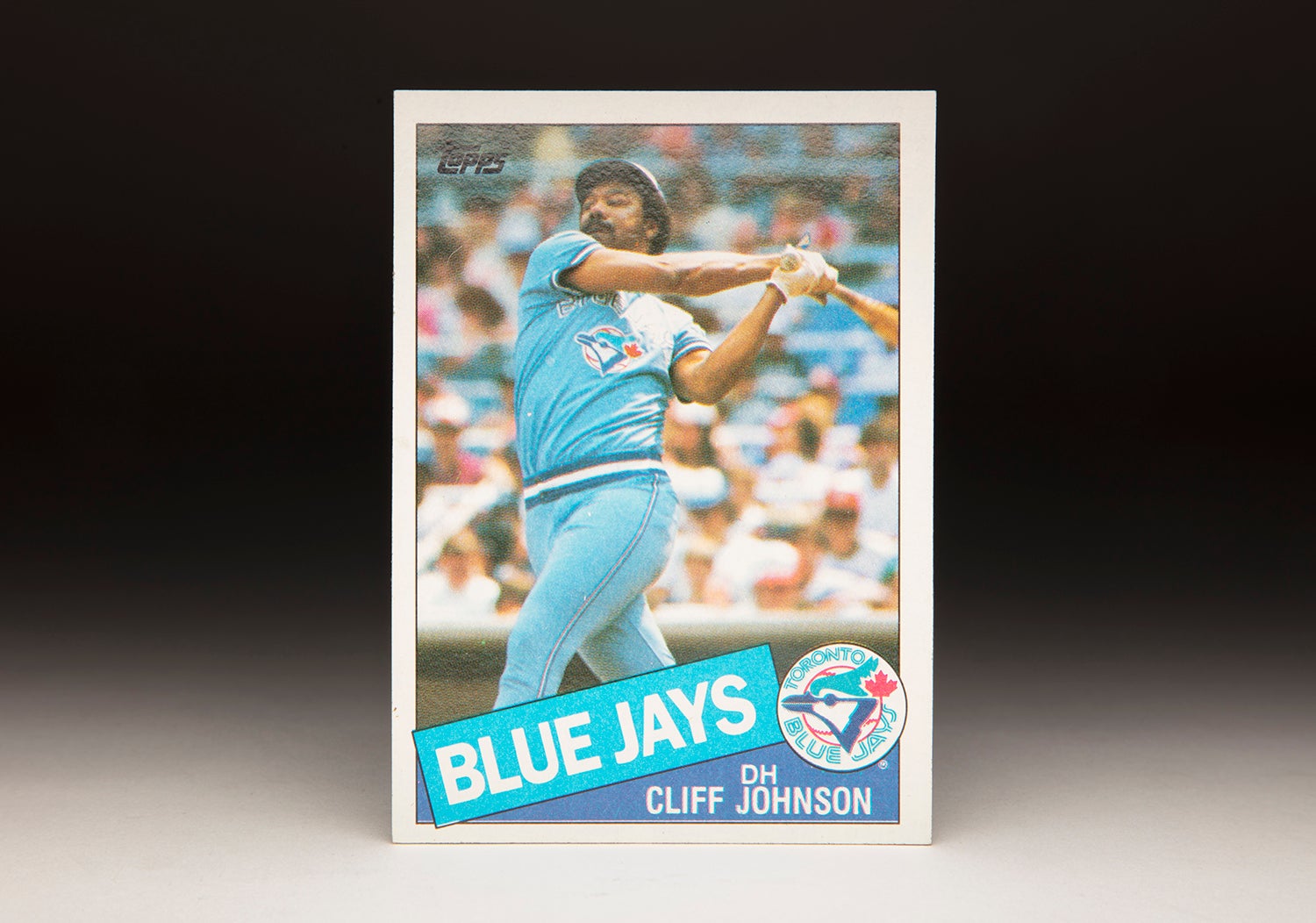

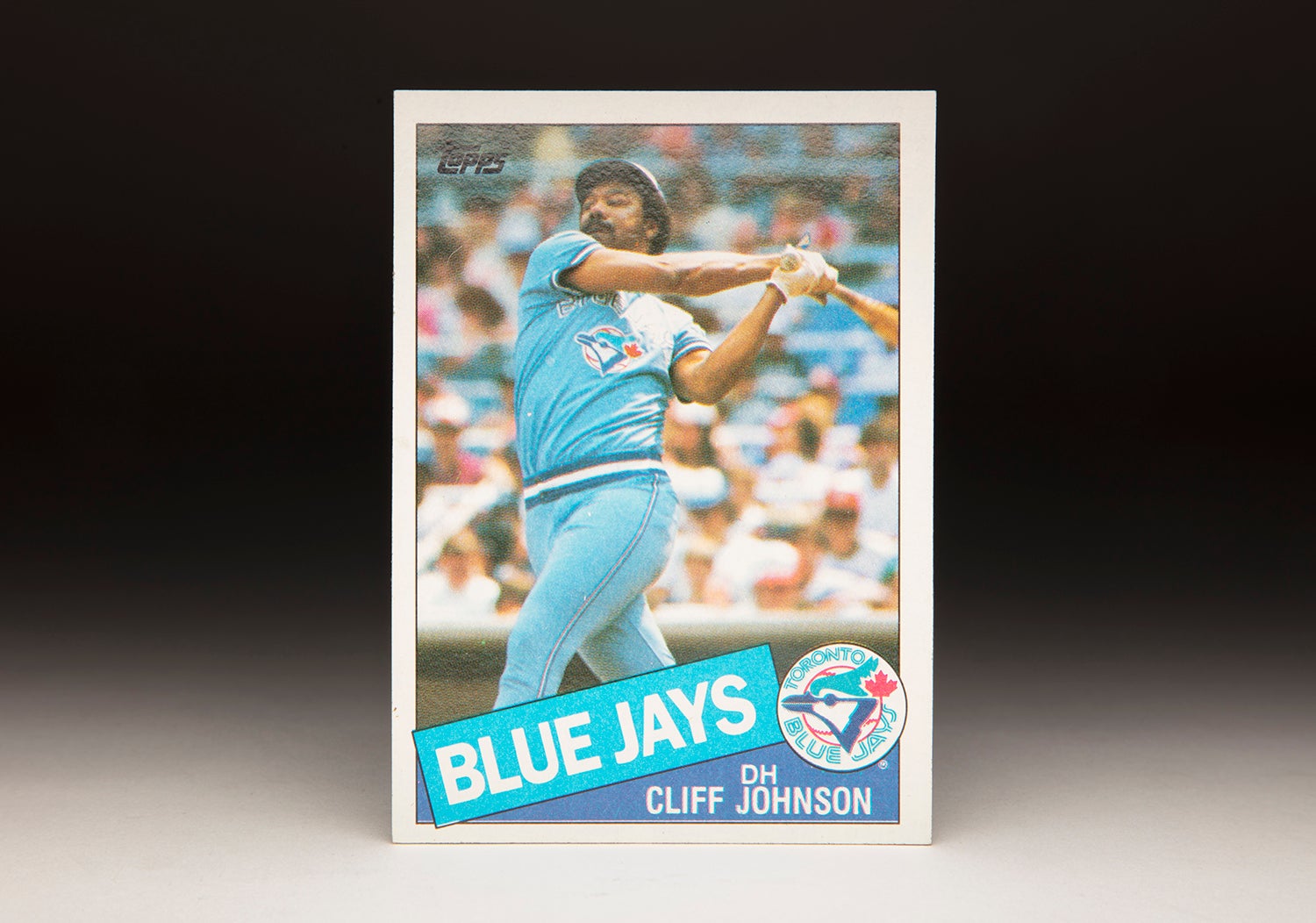

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Cliff Johnson

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah