- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Shane Rawley

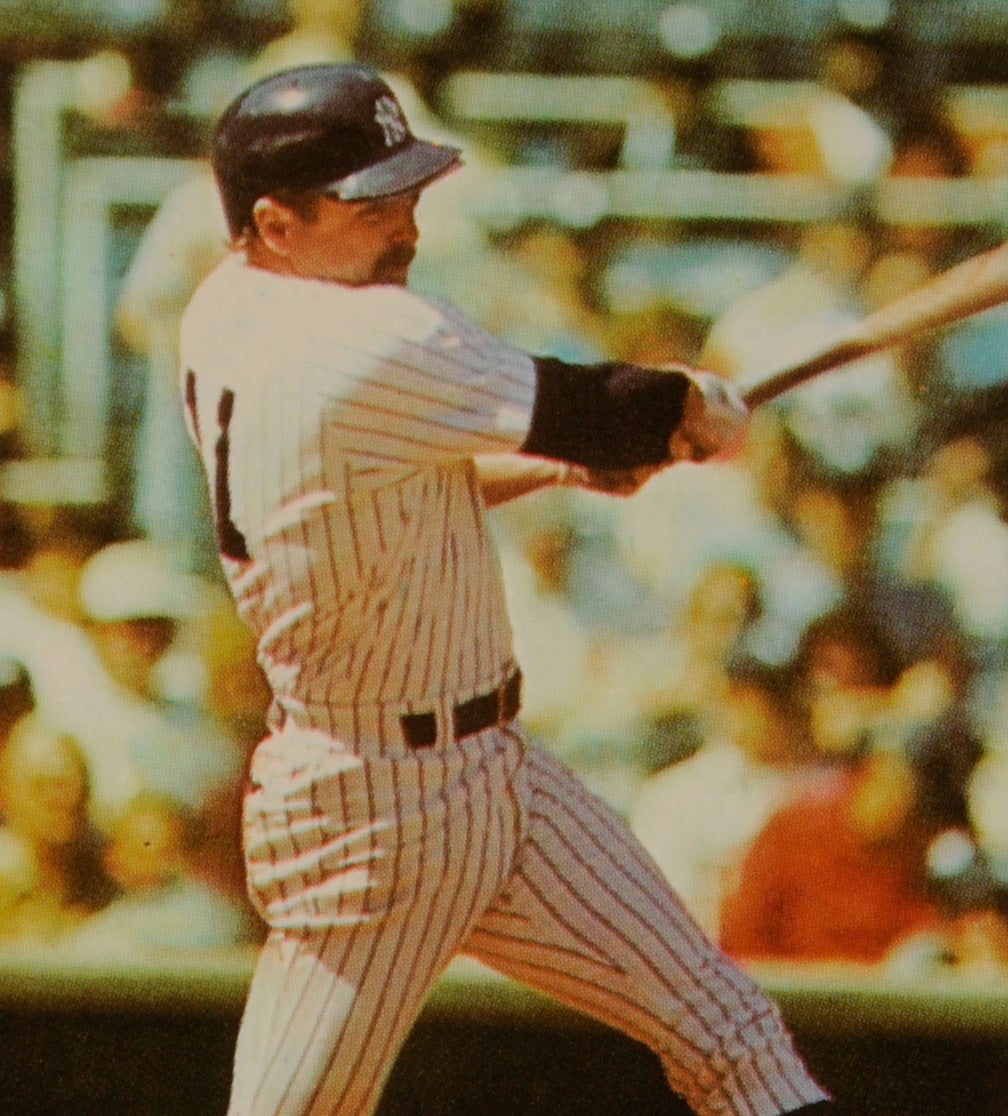

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Shane Rawley

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

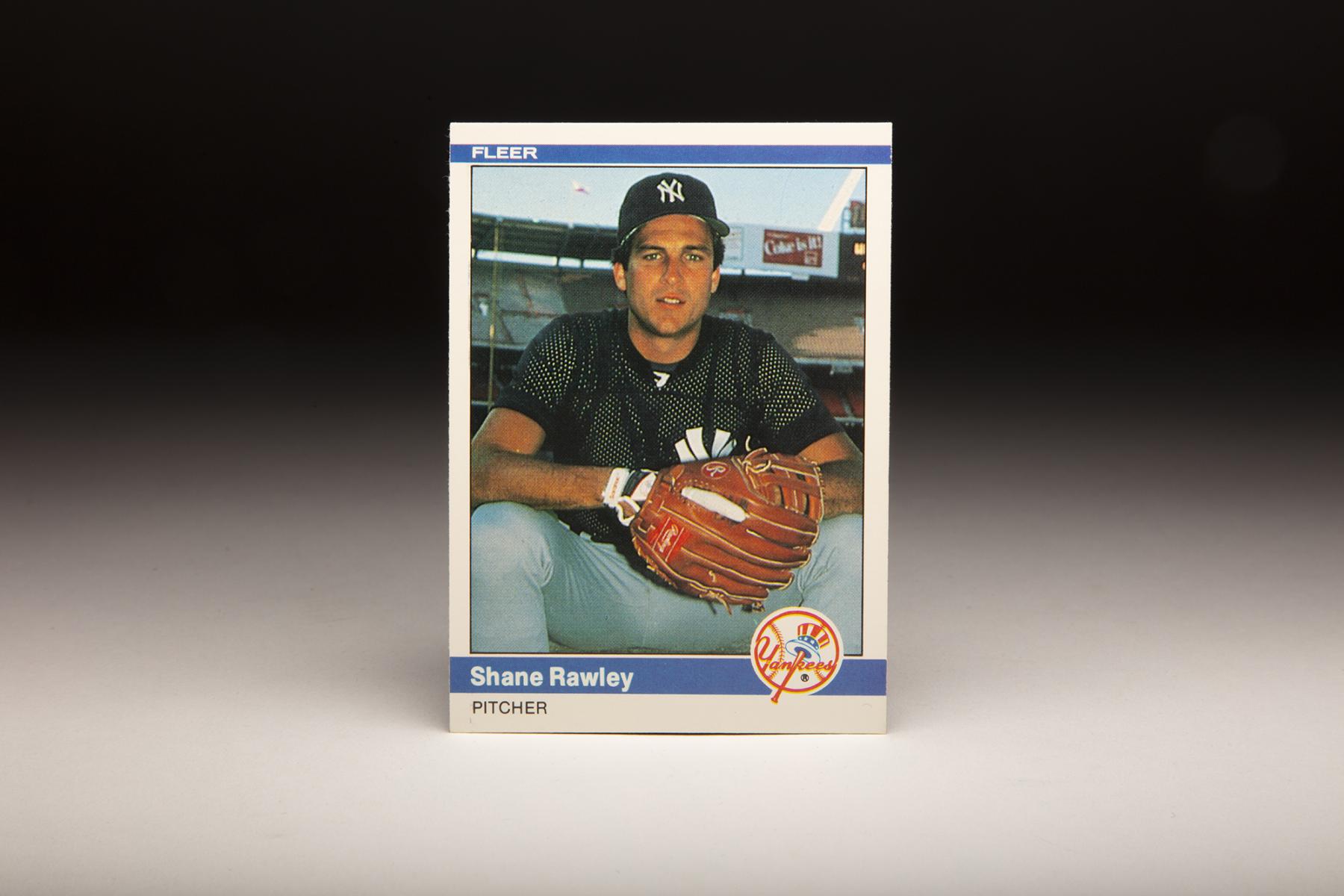

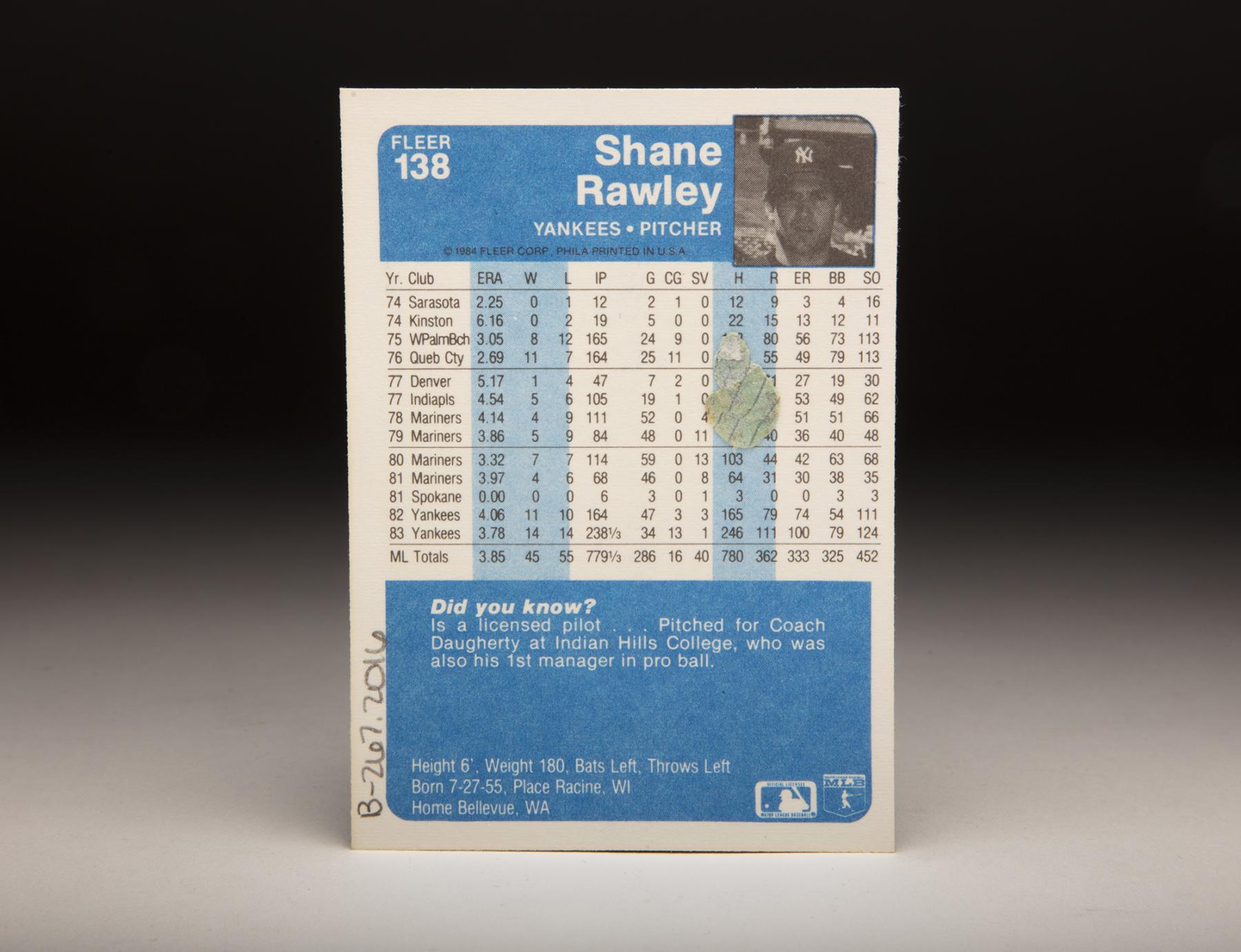

At first glance, Shane Rawley’s 1984 Fleer card looks like standard fare for 1980s cardboard, with nothing unusual or striking about it.

But if we take a closer look, we might see a few miscellaneous items worthy of note. If we focus in on Rawley’s fielding glove, we notice that he’s wearing a batting glove under the leather. This is something I’ve seen position players do from time to time, but never a pitcher. Besides, why would Rawley, an American League pitcher playing in a league with a DH, even have a batting glove at all?

Unless Rawley was out on the golf course earlier in the day, a batting glove (acting as a golf glove) just doesn’t make sense.

Let’s also take note of the jersey that Rawley is wearing. It is a mesh jersey, with a light-colored undershirt visible below. While mesh jerseys seem to have gone by the wayside in today’s game, they were used occasionally back in the 1980s. I remember the Oakland A’s wearing mesh practice jerseys, too. My guess is that some teams felt the mesh jerseys were more comfortable and breathable, but I don’t remember them ever being used in actual regular season or postseason games.

Then there is the angle of the photograph. The upper deck of the stands can be seen in the background, and while there’s nothing unusual about that, players are usually seen standing for those photos. This one is different; Rawley is clearly sitting down. There’s no chair evident, so it must be that Rawley is sitting on the top step of the dugout, with the cameraman having his back to the dugout wall. I don’t remember a card photographer ever taking a shot of a player from this angle. I’m sure that it’s been done – after all, how many millions of cards are out there? – but I just can’t remember another one.

Rawley’s arms also look unusually thin in this Fleer photograph, at least in comparison with pitchers of today. That’s understandable; weightlifting had only recently been introduced to baseball by the early 1980s, with a few players like Brian Downing leading the charge for the new manner of conditioning.

None of these characteristics seen on the card are particularly bold or glaring. They’re all fairly subtle observations. And I guess that’s appropriate for a player like Rawley, who rarely made huge headlines during his career and has become somewhat of an afterthought in baseball history.

That’s not really fair to Rawley, a good pitcher who at one time was a top notch prospect with the Seattle Mariners. Rawley took a circuitous route to Seattle; he signed with the Montreal Expos in 1974, after having been selected in the second round of the June draft. From there, he went to Cincinnati in a deal for right-hander Santo Alcala. And then at the 1977 Winter Meetings, the Reds traded him to the Mariners straight-up for speedy outfielder Dave Collins.

As a hard-throwing left-hander, Rawley put up good minor league numbers, making it odd that he would be traded twice before even making a major league roster. But the move to Seattle was a favorable stroke; as a recent expansion team, the Mariners needed help, especially in the pitching department. They included Rawley on their Opening Day roster and used him mostly as a relief pitcher, where he struggled with his control but flashed potential. Pitching in long relief, Rawley threw 111 innings and picked up four saves along the way.

In 1979, Rawley shared the closer’s role with right-hander Byron McLaughlin. He pitched well over the first half of the season, but a freakish non-baseball related injury curtailed his season. At his own birthday party, Rawley’s children were confronted by some youths outside of an establishment. Rawley, running to the defense of his children, was hit from behind, which caused him to fall and land awkwardly on his left hand. He suffered two broken bones, forcing the Mariners to place him on the disabled list.

The injury left the Mariners in panic mode. “We’re in trouble,” outfielder Bruce Bochte told Mariners beat writer Hy Zimmerman. “He’s the guy we could least afford to lose.”

Rawley would miss all of July and most of August before returning. Without Rawley, the M’s won only 11 games in July and only 12 games in August. Rawley pitched respectably down the stretch, to finish with an ERA of 3.84 and 11 saves, but the loss of seven weeks of activity dampened what could have been a far better season.

For Rawley, a breakthrough would have to wait until 1980. He walked 63 batters, but that number was inflated by 16 intentional passes. He filled the role of workhorse for the M’s, totaling 113 innings while sporting an ERA of 3.33, a very good mark given that he pitched half of the time in Seattle’s Kingdome, a favorable park to hitters.

Still only 25 years of age, Rawley seemed headed for stardom as one of the game’s elite left-handed relievers. But then came the setback of 1981. With his arm dragging from the heavy workload of 1980, Rawley saw his ERA climb to near 4.00. He walked more batters than he struck out. He saved a mere eight games. The strike of ’81 did not help matters, either. As a pitcher who was used to regular work, the interrupted season played havoc with Rawley’s routine.

As much as Rawley floundered in 1981, his left arm remained a desirable commodity around the game. Several teams expressed interest in trading for the hard-throwing closer, who featured a good fastball and an effective slider.

One of those teams was the New York Yankees.

On April 1, 1982, just before Opening Day, Mariners manager Rene Lachemann called Rawley into the office and informed him that he had been traded. This was no April Fool’s joke. The Mariners had indeed dealt Rawley to the Yankees for right-handers Gene Nelson and Bill Caudill, and a player to be named later (who turned out to be outfielder Bobby Brown).

The deal puzzled some Yankee fans. After all, the team already had Ron Davis and Goose Gossage to nail down the final three innings of close games. As soon as Rawley arrived, speculation began that the Yankees might make another trade, this one involving Davis. Ten days later, that’s exactly what happened. The Yankees traded Davis to the Minnesota Twins for hard-hitting shortstop Roy Smalley.

Davis had pitched brilliantly in a set-up role in 1981, so that put Rawley in the unenvious position of replacing an effective and popular pitcher. At first, Rawley struggled in succeeding Davis as the Yankees’ primary set-up reliever. The Yankees also noticed a disturbing trait with their new left-hander. Unlike most relievers, Rawley needed an unusually long period of time to warm up before being ready to enter a game. If a situation developed where the Yankees suddenly needed a reliever during a late-inning jam, they couldn’t always count on Rawley being fully prepared to enter the fray.

The Yankees also realized that Rawley did not rely on just his fastball and slider, but possessed a full arsenal of pitches. In July, Yankee manager Gene Michael decided to make a bold move, sliding Rawley from the bullpen to the starting rotation. Rawley took well to the change.

While his ERA as a starter was an unimpressive 4.22, his control improved considerably. Consistently giving the Yankees six to seven innings an outing, he won seven of 12 decisions, showing enough ability that the Yankees projected him to be a fulltime starter in 1983.

Rawley would deliver his best season for the Yankees in ’83. Making 33 starts, he logged a career-best 238 innings, won 14 games, and posted a solid ERA of 3.78.

Still only 27 years old, Rawley appeared ready to become a mainstay in the Yankee rotation.

Given his success in 1983, the events of the 1984 season could not have been anticipated. Plagued by shoulder trouble and sore ribs, Rawley made only 10 starts in April, May and June, and pitched so poorly that his ERA rose above 6.00. His velocity dropped significantly, to the point that Yankee catcher Butch Wynegar had difficulty distinguishing between Rawley’s fastball and his change-up.

Trade rumors began to envelop Rawley. One rumor had him going to the Philadelphia Phillies for Gold Glove center fielder Garry Maddox. For his part, Rawley did not want to leave the Yankees. “I like it here,” the left-hander told the Sporting News. “I enjoy being a Yankee. And I think I can win a lot of games for them.”

In June, the unwanted trade became reality. The Yankees dispatched with Rawley, sending him to the Phillies, but not in a deal for Maddox. Instead, the Yankees settled on injury-plagued right-hander Marty Bystrom and minor league outfielder Keith Hughes. Just like that, Rawley was an ex-Yankee, and his 1984 Fleer card was now out of date.

The change of teams and leagues did wonders for Rawley. Immediately inserted into the Phillies’ rotation, he won 10 of 16 decisions and lowered his ERA to 3.81. The following year, he pitched even better, as evidenced by his career best 3.31 ERA. He would remain effective over the next two seasons, winning a combined 28 games and earning an All-Star Game selection in 1986.

That same summer, Phils pitching coach Claude Osteen raved about Rawley. “Shane’s genuinely interested in being the best pitcher on our staff, and I think he has become that,” Osteen told the Albany Times Union. “He likes the idea of being the man we look to when we need to stop a losing streak or win a big game… [Lefty] Steve Carlton always responded to a challenge, and Shane does, too.”

Unfortunately, Rawley’s season hit a major setback in late July, when he suffered a fractured bone below his shoulder while delivering a pitch. Rawley heard a “crack” as he released the ball and immediately felt pain in the back of his shoulder. At the height of his success, Rawley’s season had come to an end.

In 1987, Rawley made a strong comeback and accumulated a career high total of 123 strikeouts. The following year, a lack of run support contributed to an 8-16 record. After the season, the Phillies traded their onetime ace to the Minnesota Twins for a three-player package that included veteran second baseman Tom Herr and catcher Tom Nieto.

The 1989 campaign would turn out to be Rawley’s final major league season. His ERA soared to 5.21, while his strikeout rate dropped precipitously. After the season, Rawley moved on to free agency, but in this case, free agency simply translated into a difficult job search. He settled for a non-guaranteed contract with the Boston Red Sox, who brought him to Spring Training. But Rawley failed to make the Red Sox’ roster, his career coming to an end at the age of 33.

Rawley’s association with baseball also ended with his retirement as a player. Toward the latter stages of his career, he had decided to dabble in screenwriting. More specifically, he wrote a script for a baseball-themed episode of Miami Vice, the hit show on NBC. “I did it on a whim and sent it in,” Rawley told USA Today. “They sent it back, said it had some merit, and [said] thanks, but no thanks.”

Rawley also tinkered with a novel, but it did not reach the publishing stage. The novel centered on the theme of flying, another one of his interests. A licensed pilot, Rawley once owned a Cessna 182 before deciding to sell the aircraft.

Settling in Sarasota, Fla., Rawley turned to the restaurant business. He now owns “Shaner’s,” an establishment that specializes in thin-crust pizza. Rawley is known to socialize with many of his dining patrons, often performing card tricks for younger family members in attendance.

It has been a long, winding road for Rawley. While he never quite became the star that the Yankees and Mariners had anticipated, he did become a very good pitcher in Philadelphia. And while Miami Vice rejected his attempt at television glory, Rawley has found success pitching pizzas instead of fastballs.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

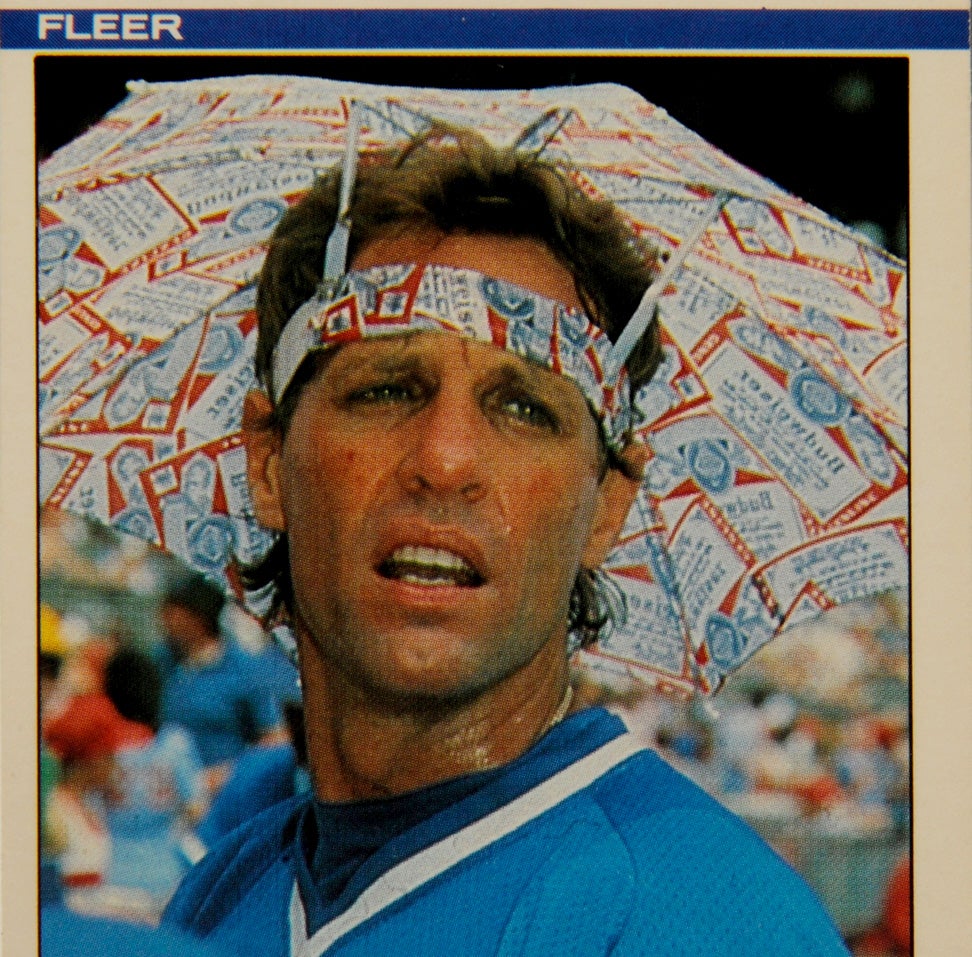

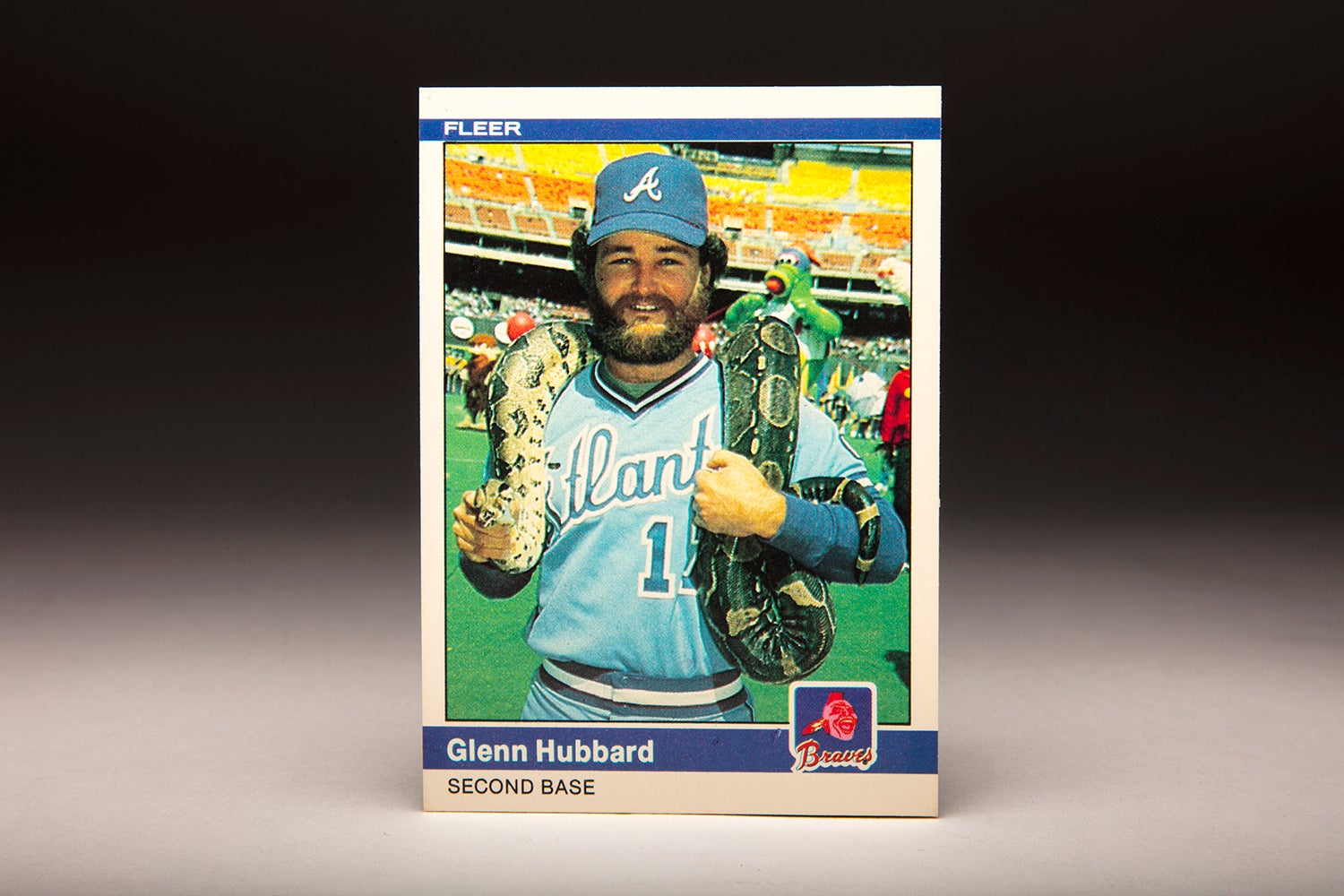

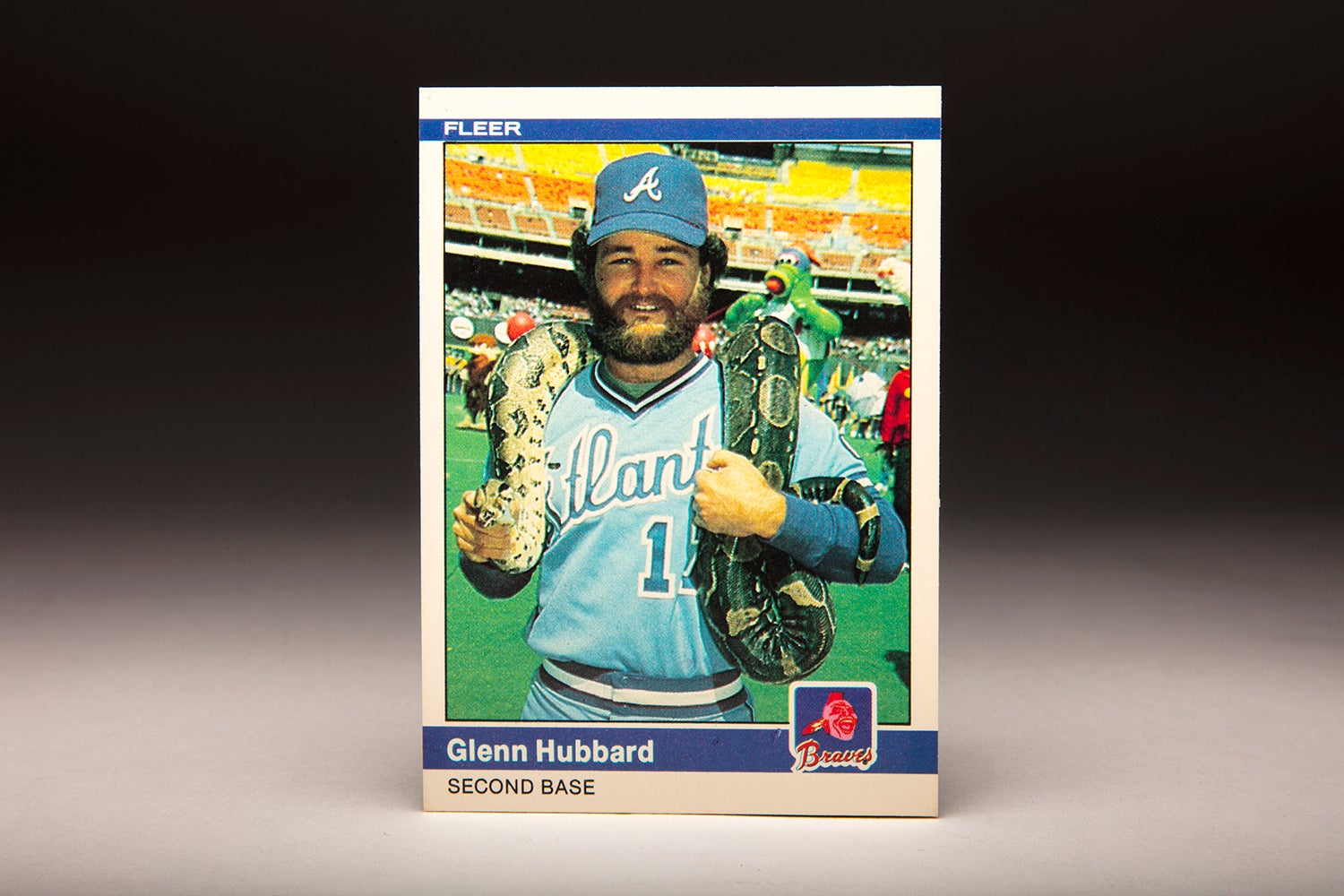

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Glenn Hubbard

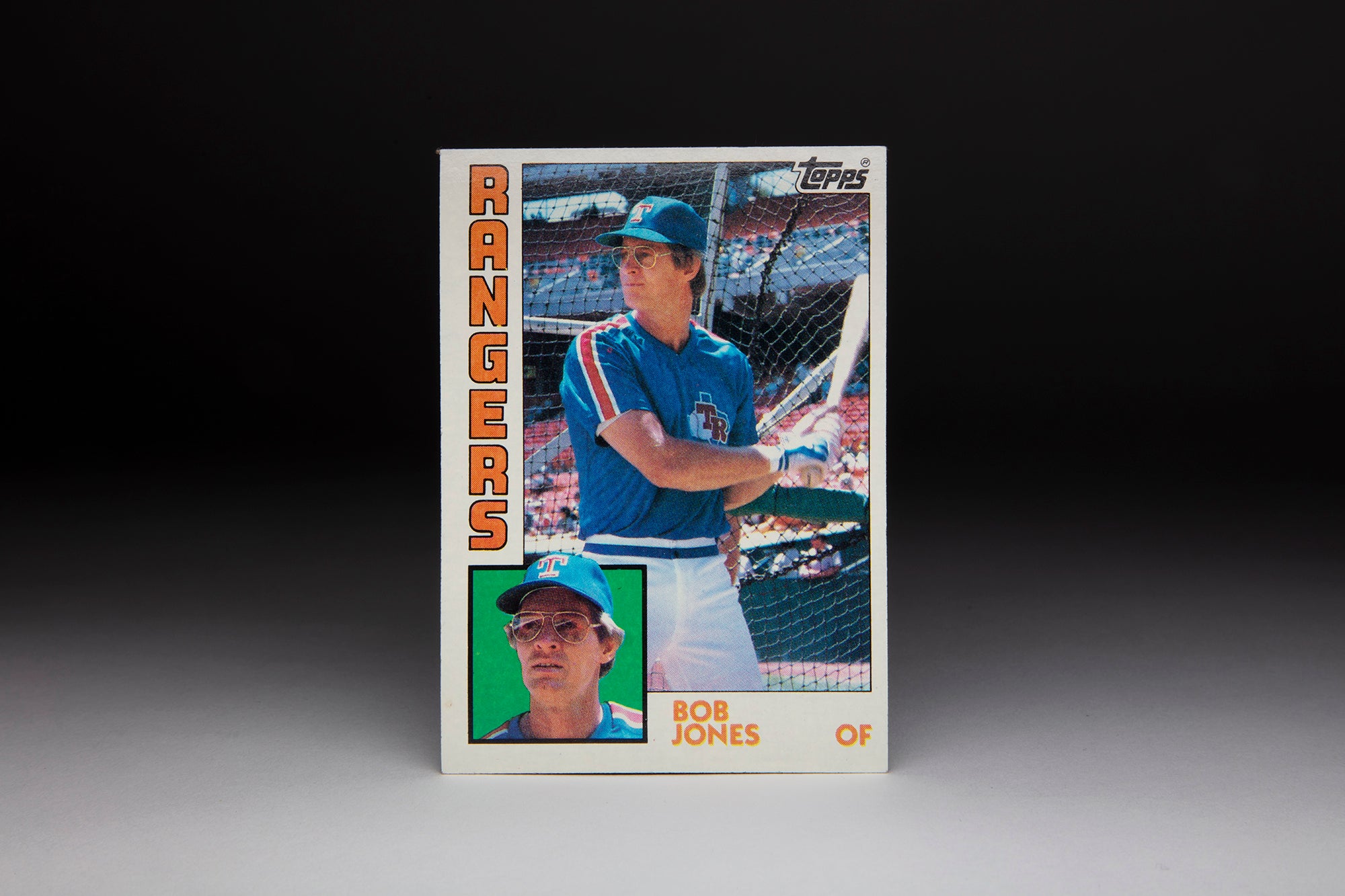

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Bob Jones

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1984 Fleer Glenn Hubbard