- Home

- Our Stories

- Hall of Fame statue garden a gem hidden in plain sight

Hall of Fame statue garden a gem hidden in plain sight

The inspiration for one of the Hall of Fame’s most charming features comes from a college campus in Boston. You’ll find it tucked between Churchill Hall and the Barletta Natatorium, in a cozy courtyard ringed by oak trees at Northeastern University: A granite home plate, 60 feet 6 inches from a statue of the great Cy Young, marking the site of the first World Series game — between the Pittsburgh Pirates and Boston Americans — in 1903.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

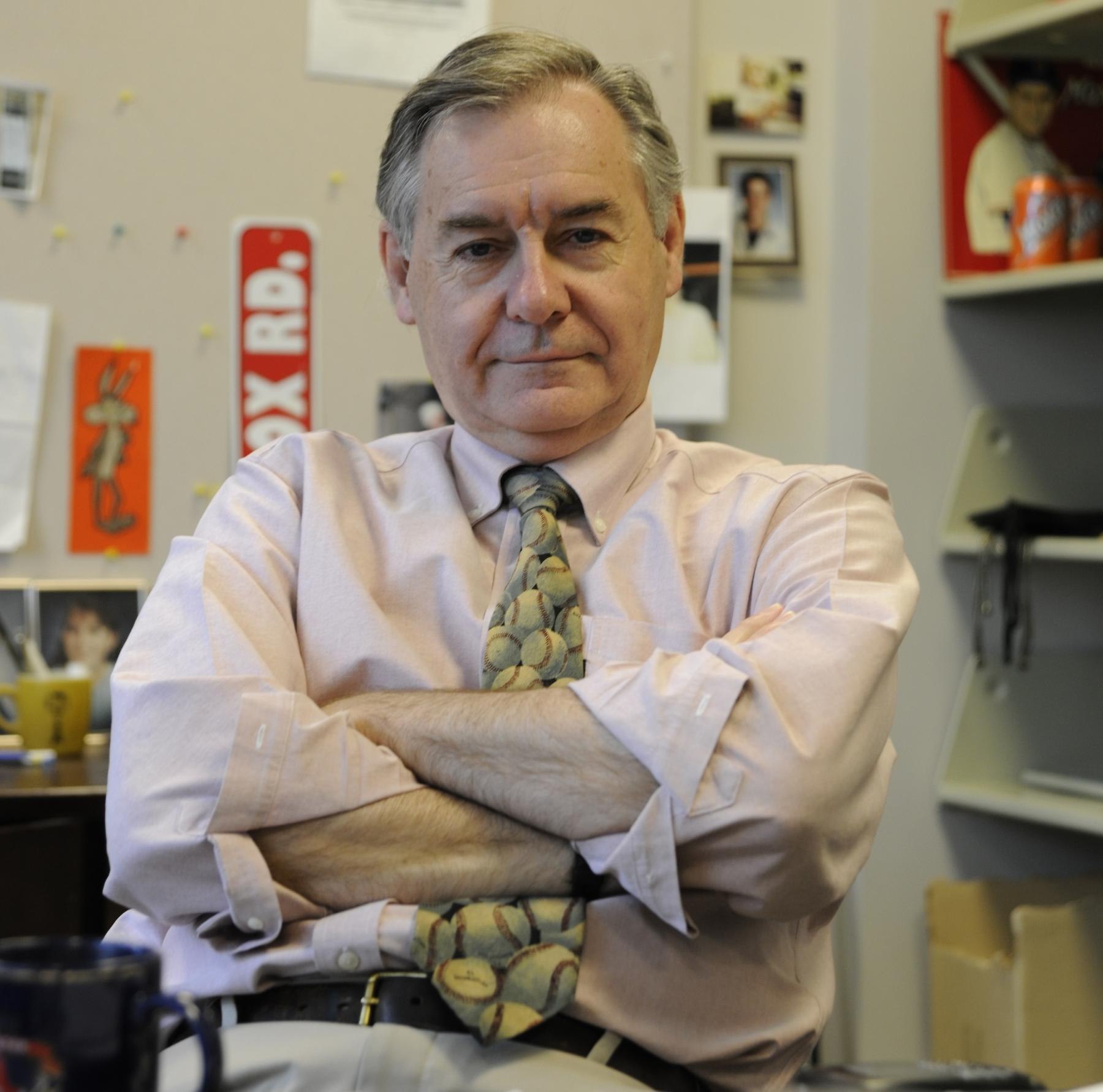

Ted Spencer, the former curator of the Hall of Fame, thought of this in 2001 when the Hall’s chairman, Jane Forbes Clark, told him of a new donation: A pair of statues depicting the winning battery from Game 7 of the 1955 World Series. Sheldon Fireman, a New York restaurateur, had given the statues of Johnny Podres and Roy Campanella that were intended for a diner he owned in Brooklyn.

Sculpted by Stanley Bleifeld, they were masterpieces, to be sure, perfect for the lawn between the Library and the Plaque Gallery — but not quite in the manner that Spencer initially envisioned.

“I first looked at it and said, ‘Gee, I wonder if I can make a diamond out of this space where they would be the focus of it, and the baselines would be a path and the four bases would be benches,’” said Spencer, who worked for the Hall from 1982 to 2009 and still lives in Cooperstown. “Well, that didn’t work out, because 90 feet is a heck of a lot bigger than I assumed.”

Then Spencer remembered the scaled-down setup at Northeastern — on the site of the old Huntington Avenue Grounds — and thought that could work in Cooperstown, too. And so it does, with a cobblestone pathway connecting Podres and Campanella from that magical distance of 60 feet 6 inches.

Spencer laughed as he recalled the installer asking him why it had to be so precise. He underestimated the fastidiousness of baseball fans.

“That was in the morning, and when I went out at lunchtime as he was cleaning up, the guy goes, ‘Everybody who came out here to see what I was doing said exactly that: ‘Is it 60 feet, six inches away?’” Spencer said. “I told him: ‘See, you’ve got to know your audience. It matters!’”

The presence of the statues made an impact inside the Hall, too. The ramp leading from the Plaque Gallery up into the atrium of the Library used to have a wooden wall, Spencer said, but once the sculptures were installed, Clark decided to have the wall redone. Now it is made of glass so visitors can admire the statues from inside or out.

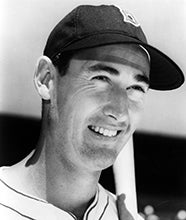

While Campanella, a three-time National League MVP, was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1969, Podres slipped off the ballot. Yet his 2-0 shutout in the 1955 finale has historical resonance as the only World Series clincher in the history of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“It meant a lot to a lot of people,” Podres said in an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2005, three years before he died at age 75. “Sometimes when I’m home doing nothing, I put the video in. I get the feeling that I’m young again. What a time that was.”

Podres had a stellar career, with 148 victories and three more championships with the Dodgers after the franchise moved to Los Angeles in 1958. But highlighting his statue-worthy moment helps underscore the mission of the Hall of Fame: It’s about much more than the folks who have the plaques.

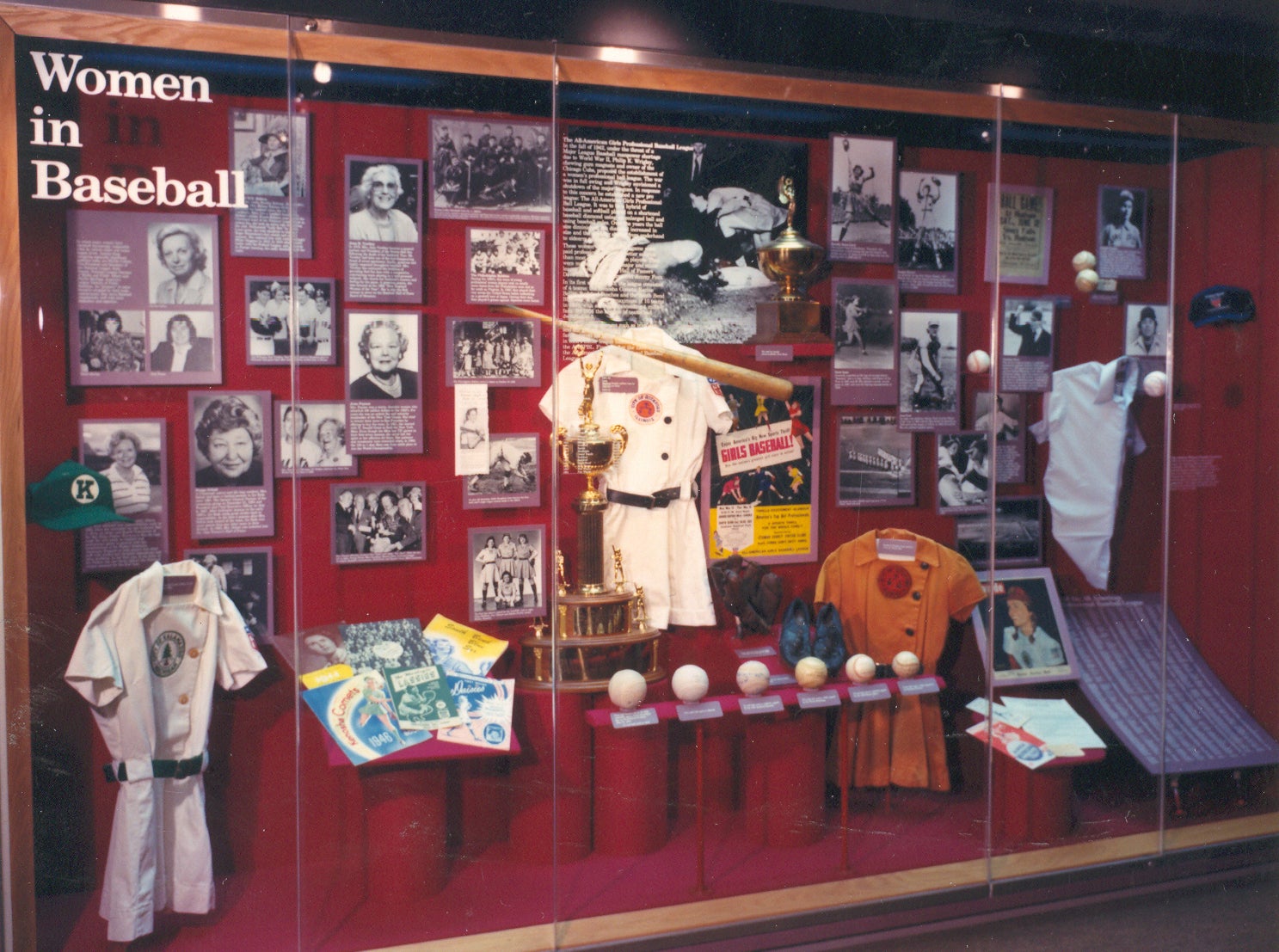

The Museum’s statue garden, located between the Plaque Gallery and the Library adjacent to Cooper Park, features artwork of Johnny Podres and Roy Campanella, Satchel Paige and an All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

“We are a legitimate American history museum, like the Smithsonian of baseball,” Spencer said. “Whenever I give a tour, it’s the first thing out of my mouth: ‘I know we’ve just walked through the (Plaque Gallery), and I know you know all about those guys, but that’s not what we do. We conserve and then we tell the story of an incredible part of America’s history of culture as it relates to baseball.’”

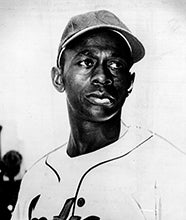

In 2006, the Museum added two more statues to the garden that serve to emphasize the depth of that cultural impact. One depicts Satchel Paige in his Kansas City Monarchs uniform, his left leg thrust skyward as he leans back to deliver a pitch. The other, “Woman At Bat,” shows a right-handed hitter from the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League following through on a swing.

“It was part and parcel with trying to send a more inclusive message,” Spencer said. “Including those two sculptures out there just helps to flesh out our mission.”

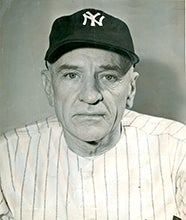

Before the Induction Ceremony was moved to the Clark Sports Center in 1992, they were often held on the steps of the Library in Cooper Park. But Spencer believes — based on photos from the time — that the adjacent statue-garden site was the spot for the 1966 Induction Ceremony for Ted Williams and Casey Stengel, which featured one of the most impactful speeches in the history of the event.

Williams used the occasion to push for the inclusion of Paige and Josh Gibson in the Hall “as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here only because they were not given a chance.” Paige would be inducted in 1971, and Gibson the following year — opening the door for dozens of Negro Leagues legends.

All four statues were created by Bleifeld (1924-2011), whose statues of Lou Gehrig, Roberto Clemente and Jackie Robinson represent character and courage and greet visitors in the Hall’s main lobby, right by the ticket booths. A Brooklyn native, Bleifeld’s most famous works outside of Cooperstown are “The Lone Sailor” and “The Homecoming” at the U.S. Navy Memorial in Washington, D.C.

“I remember visiting Washington, D.C., sometime after we had installed the two Brooklyn sculptures,” said Spencer, who served in the Navy during the Vietnam era. “I was outside the Navy building and there was this marvelous sculpture called ‘The Lone Sailor,’ and I was quite moved by it. I thought it was awesome, having identified with the uniform, and then I realized when I read the label that Stanley had done that as well. It was a real thrill.”

And the thrill of a lifetime for Brooklyn fans has a permanent place in Cooperstown.

Tyler Kepner has covered baseball for more than 30 years. He is the author of the best-selling “K: A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches” (2019) and “The Grandest Stage: A History of the World Series” (2022), both published by Doubleday.

Related Stories

#Shortstops: Atlanta Mystery Solved in Cooperstown

30 years ago, the AAGPBL came to Cooperstown

Oral history provides rare look into Cy Young’s life after baseball

Red Sox trade Cy Young to Cleveland

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Hall of Fame statue garden a gem hidden in plain sight

Judy Johnson elected to the Hall of Fame

Hall of Fame Staff Members Answer Pro Football Hall of Fame #ALSIceBucketChallenge

Hall of Fame statue garden a gem hidden in plain sight

The Return of Hank Greenberg

Play It Again: The Two All-Star Game Era

When Baseball Stepped to the Plate for Finns

Joe DiMaggio makes his big league debut, recording three hits in the Yankees’ win

Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines, Iván Rodríguez Elected to Hall of Fame by Baseball Writers’ Association of America

01.01.2023