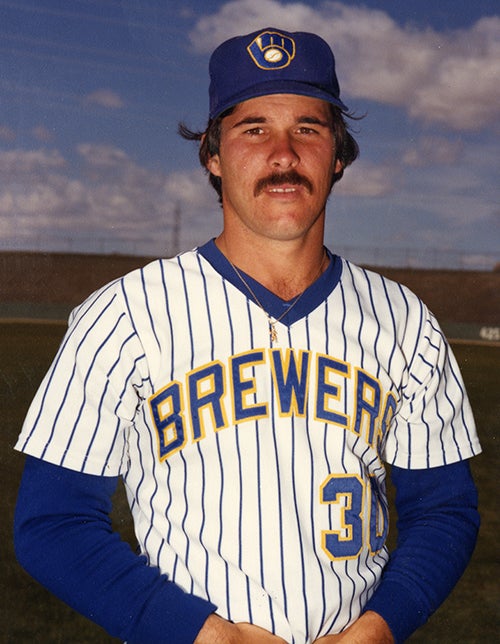

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Moose Haas

His nickname belied his stature and girth, as Moose Haas was an averaged sized big league pitcher for 12 seasons with the Brewers and the Athletics.

But Bryan Edmund Haas often found himself in the game’s biggest moments of his era.

Born April 22, 1956, in Baltimore, Haas was given his nickname right after he was born by his father.

“I wasn’t that big, but he thought I was going to grow up to be real big,” Haas told the Journal Times of Racine, Wis. “That’s why he called me Moose. It wasn’t because I was a big Bullwinkle fan or anything.”

Haas pitched for much of his career at 6-foot and 170 pounds. But from the time he was in high school, Haas performed at a level that was bigger than his size. He lost just once as a sophomore at Franklin High School in Reisterstown, Md. (located in the northwest suburbs of Baltimore) and once more as a junior, going 6-1 with 78 strikeouts in 42 innings in the latter year.

Haas continued to dominate as a senior – going 7-0 with 95 strikeouts in 49 innings – and was widely regarded as the best pitcher in the Baltimore area. He made it known that he preferred to pitch in the pros immediately rather than going to college, though he committed to Clemson University just in case he didn’t get the offer he wanted from an MLB team.

“I want to get an education, study criminology and law and work for the FBI eventually,” Haas told the Baltimore Evening Sun as a high school senior. “But I’d like play pro ball first.”

The Brewers took Haas in the second round with the 30th overall pick in the June 1974 MLB Draft, and he quickly signed and was sent to Newark of the New York-Penn League, where he went 5-5 with a 3.19 ERA in 13 starts. In 1975, Haas pitched for Burlington of the Class A Midwest League, where he went 11-8 with a 2.05 ERA in 171 innings.

Haas skipped Double-A and went to Triple-A Spokane in 1976 as manager Frank Howard raved about Haas’ ability to throw strikes.

“His fundamental skills are far beyond that of an (Class) A pitcher,” Howard told the Spokane Chronicle during Spring Training.

Haas proved Howard correct, going 13-9 – albeit with a 5.55 ERA – in the hitter-friendly Pacific Coast League in 1976. The Brewers brought Haas to the majors at the tail end of that season, and Haas debuted against the Yankees on Sept. 8, allowing just one run over three innings against the eventual American League champions. Haas made his first start on Sept. 21 against Boston and finished the big league campaign with an 0-1 record and 3.94 ERA in five appearances.

The Brewers gave Haas a chance to make their starting rotation in the spring of 1977, and Haas sparkled during exhibition play with a 5-0 record and 1.13 ERA.

“Moose just had a great spring,” Brewers manager Alex Grammas told the Associated Press. “We gave him the opportunity and he made the most of it. He can be an outstanding pitcher.

“The thing about him is, he doesn’t say much but he is a real tough competitor. Competition to him is as natural as getting out of bed in the morning.”

Haas started the Brewers’ third game of the 1977 season and allowed just one run over 7.2 innings en route to his first big league win in a 2-1 victory over the Yankees. He tossed the first of his six complete games that year May 13 against the Tigers and finished the season with a 10-12 record and 4.33 ERA over 32 starts. Haas was named the Brewers’ Rookie of the Year.

Haas began the 1978 season with a flourish, throwing a complete game in Milwaukee’s second contest of the year – a 16-3 win over the Orioles – and setting a team record for strikeouts in one game four days later with 14 Ks against the Yankees.

“That was pitching, fellas,” Milwaukee manager George Bamberger told reporters after Haas’ record-setting game. “I said before (Haas) could win 18 games this year, and if he can win 18, he can win 20.”

But the back-to-back complete games may have put a strain on Haas, who was tagged for six earned runs over 5.1 innings by the Orioles in his next start. Then on April 20, Haas tore a muscle in his elbow during a start against the Red Sox and left the game in the second inning. He was sidelined until June when he made two more ineffective starts, then was out of action until making a three-inning relief appearance in the Brewers’ final game of the season.

“I heard (the arm) pop and Butch Hobson, the (Red Sox) runner on third, heard it, too,” Haas told the Wisconsin State Journal in the spring of 1979. “I was scared. I admit it. Here I was, 21 years old, and I thought my career might be over.”

Haas pitched in just seven games in 1978 and was 2-3 with a 6.16 ERA. But the outing in Milwaukee’s final game of the season convinced him that he was on the mend, and Bamberger took advantage of several early-season off days in 1979 to ease Haas back into the rotation. He threw his first career shutout against Cleveland on July 21 and regularly made his scheduled starts, going 11-11 with a 4.78 ERA in 184.2 innings.

Then in 1980, Haas – still only 24 years old – became the Brewers ace by leading the team in victories (16), complete games (14), innings pitched (252.1) and strikeouts (146) while posting a 3.10 ERA. Milwaukee posted its third straight winning season and then added future Hall of Famers Rollie Fingers and Ted Simmons in an offseason trade with St. Louis, creating championship expectations for 1981.

Haas and the Brewers did not start quickly in ’81. Haas was 5-4 with a 4.56 ERA when the strike interrupted the season in June, and Milwaukee was in third place in the AL East at that point. But when the season resumed in August, the Brewers had a clean slate with the advent of the split-season concept. Haas won three of his first four starts and finished the season with a record of 11-7, helping Milwaukee win the second-half division title. In his final regular season start of the year, Haas pitched a complete game against Detroit, allowing only two runs in an 8-2 win that put the Brewers one victory away from their first postseason appearance.

The next day, the Brewers defeated the second-place Tigers again to clinch the second-half division title.

“Haas rose to the occasion,” Brewers manager Buck Rodgers told the Chicago Tribune after Haas’ complete game.

Haas called it “the most important game of my life.”

In the ALDS vs. the Yankees, Haas started Game 1 and allowed four runs over 3.1 innings in a 5-3 Milwaukee loss. The series went to the deciding fifth game, where Haas started again and allowed three runs over 3.1 innings in a 7-3 defeat that eliminated the Brewers.

But despite the loss, Milwaukee appeared to be on the verge of a championship run. And in 1982, it all came together after Harvey Kuenn replaced Rodgers as manager on June 2.

In Kuenn’s first game as manager, Haas allowed just three hits and one run over six innings as the Brewers beat Oakland 10-1. Haas then won four of his five decisions in July as the Brewers got hot. But with the acquisition of Don Sutton on Aug. 30, Haas lost his spot in the rotation.

“I hadn’t been throwing the ball that well,” Haas told the Chicago Sun-Times. “I didn’t look at going to the bullpen as a demotion because Don Sutton is going to start wherever he goes.”

In the season’s next-to-last game, Haas allowed just one unearned run in four innings in relief of starter Doc Medich in Baltimore’s 11-3 victory that left the teams with identical 94-67 records heading into the final game. The in the finale, Milwaukee won 10-2 behind Sutton to clinch the AL East title.

In the ALCS vs. the Angels, Milwaukee lost the first two games but returned home to win Game 3. In Game 4, Haas blanked California through five innings – and no-hit the Angels through 5.2 innings – as the Brewers put up six runs. It was 7-1 Milwaukee through seven when Haas allowed a grand slam to Don Baylor that cut the lead to two runs. But Jim Slaton retired all five batters he faced in relief of Haas – and Milwaukee scored twice in the eighth to win 9-5.

“I didn’t really expect to start one of these games,” Haas told the Sun-Times. “I hadn’t started for a month.”

When the Brewers completed their series comeback by winning Game 5, Haas found himself in the World Series against the Cardinals. There, Kuenn once again turned to Haas in Game 4, and Haas pitched 5.1 innings, allowing four earned runs in a game Milwaukee won 7-5. Haas faced former Milwaukee prospect Dave LaPoint in that game, and LaPoint and Haas had become good friends while both were with the Brewers.

“We did a lot of things together,” Haas told the AP of LaPoint. “We both had the same minor league pitching instructor (Al Widmar).”

Haas would appear in one more game in the World Series, relieving Bob McClure in the sixth inning of Game 7 and extinguishing a Cardinals rally that saw St. Louis take a 4-3 lead. Haas pitched a perfect seventh inning but ran into trouble in the eighth. Mike Caldwell relieved Haas with two on and two outs and allowed singles to Darrell Porter and Steve Braun that increased the Cardinals lead to 6-3.

Bruce Sutter retired the Brewers in order in the ninth to wrap up the title.

In 1983, Haas found himself back in the Brewers’ rotation and won eight straight decisions in July and August, including back-to-back shutouts of the Blue Jays and Royals. He also signed a three-year extension reported to be worth slightly more than $2 million during the year.

But he made only one start in September due to what was called a “tired arm” and finished the year with a 13-3 record – good for an .813 winning percentage that led the AL – and 3.27 ERA in 179 innings pitched.

Still only 27 years old on Opening Day of 1984, Haas went 9-11 that season with a 3.99 ERA as the Brewers suffered their first losing season since 1977. Then in 1985, Haas made his first Opening Day start allowing only one earned run over eight innings but taking the loss in a 4-2 White Sox victory. Haas was 7-3 with a 2.38 ERA through June 29 after pitching a one-hitter against New York at Yankee Stadium – denied history only by a seventh-inning double by Don Mattingly.

But Haas struggled in the second half of the season and finished 8-8 with a 3.84 ERA. It would be his final season taking a regular turn as a starting pitcher.

On March 30, 1986, the Brewers traded Haas to the Athletics for Steve Kiefer, Charlie O’Brien and two minor leaguers as Milwaukee committed to a youth movement.

“When (the Brewers) told me they were trading me, they asked me where I wanted to play,” Haas told the Press Democrat of Santa Rosa, Calif. “Since I was building a home in Scottsdale (Ariz.), I told them I’d go to any team that trained around there.”

As a 10-and-5 player, Haas could have rejected any trade but welcomed the chance for a new start with the A’s.

“I’m happy to be wanted,” Haas told the Press Democrat. “There wasn’t that feeling any longer in Milwaukee.”

Haas started the season 6-0 and was 7-1 with a 2.54 ERA when he left his May 21 start vs. the Yankees after only two innings due to a sore shoulder that was later diagnosed as bursitis. He made only three appearances the rest of the year, finishing with a 7-2 mark and 2.74 ERA in 12 starts.

The A’s brought Haas back in 1987 but after one start in Spring Training he was sidelined with a pulled muscle in his shoulder. He worked his way back into the rotation in May and made nine starts before sitting out the rest of the season with a sore elbow that required surgery.

Haas looked for work in 1988 and the Giants gave him a tryout before turning to other options. Haas did not appear in a big league game after the 1987 season and finished his career with a record of 100-83 and a 4.01 ERA, having never pitched a game at an age older than 31.

When he wrapped up his Brewers career prior to the 1986 season, he was third in innings pitched (1,542) and wins (91) and second in strikeouts (800).

“I’m really not looking to be known as a Cy Young candidate or one of the better right-handers in the league,” Haas told the Wisconsin State Journal prior to the 1984 season. “I’m just looking to do the best I can for this team and try to stay above .500 as much as I can.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum