- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1974 Topps Boog Powell

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Boog Powell

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

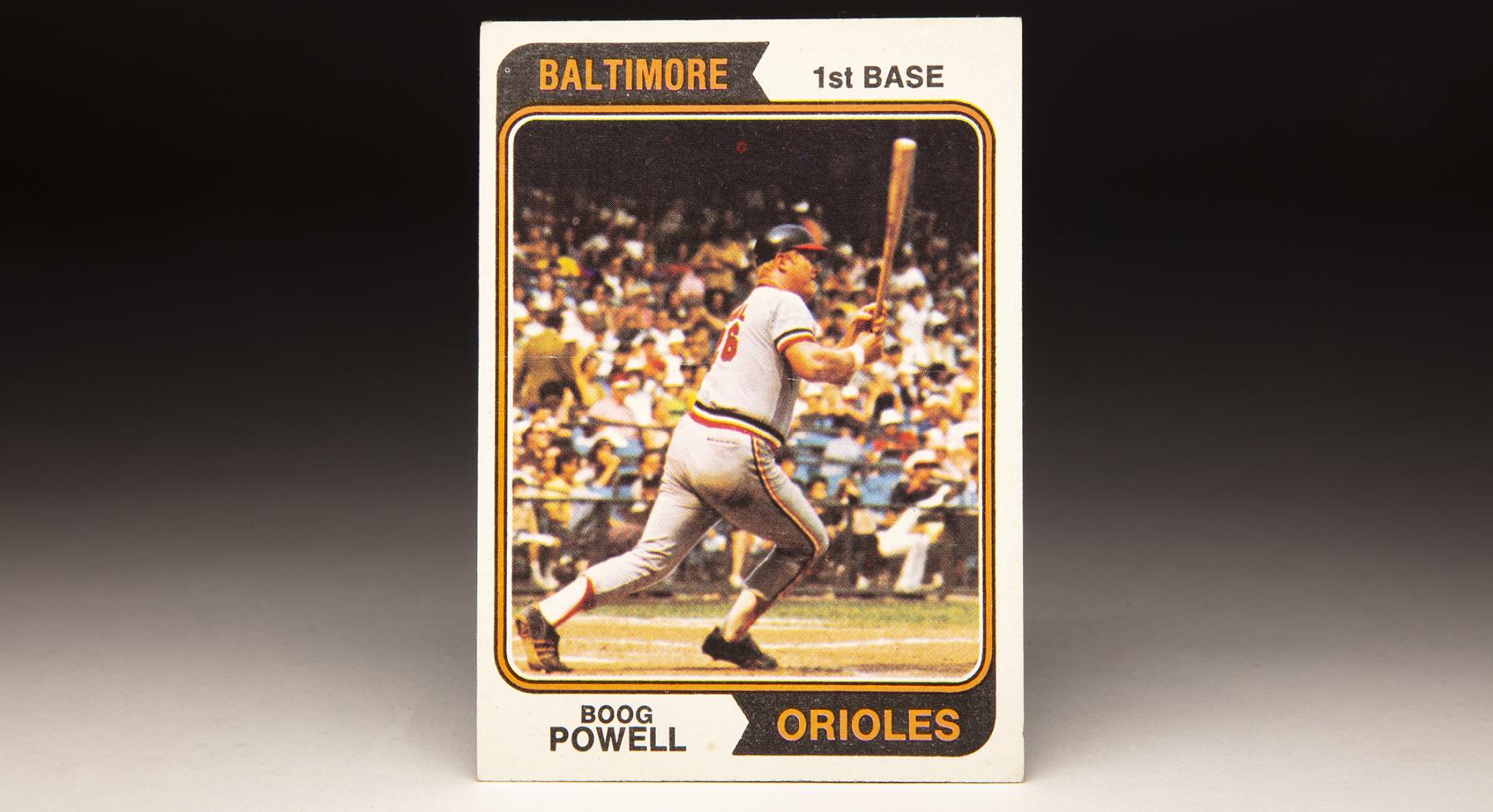

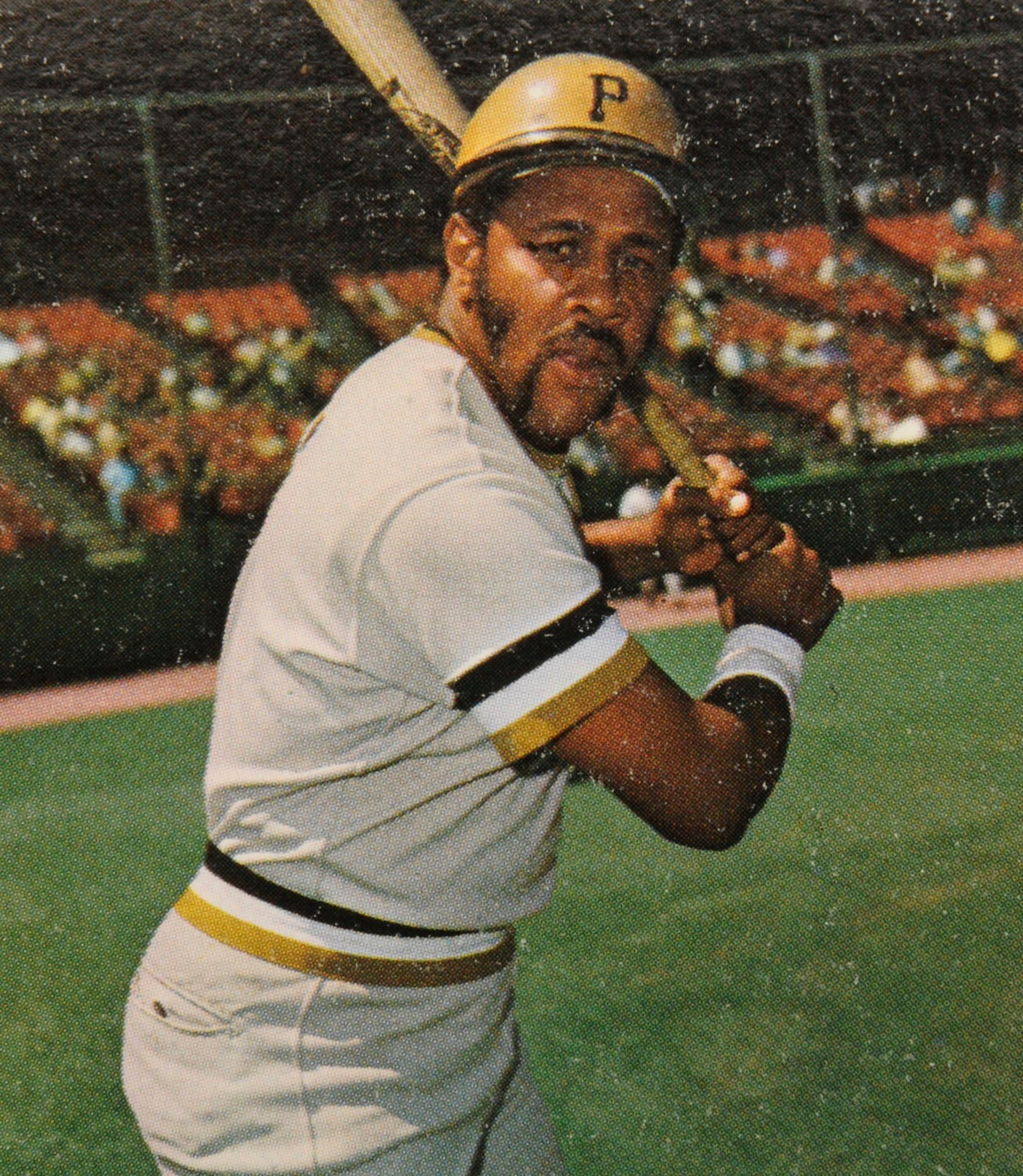

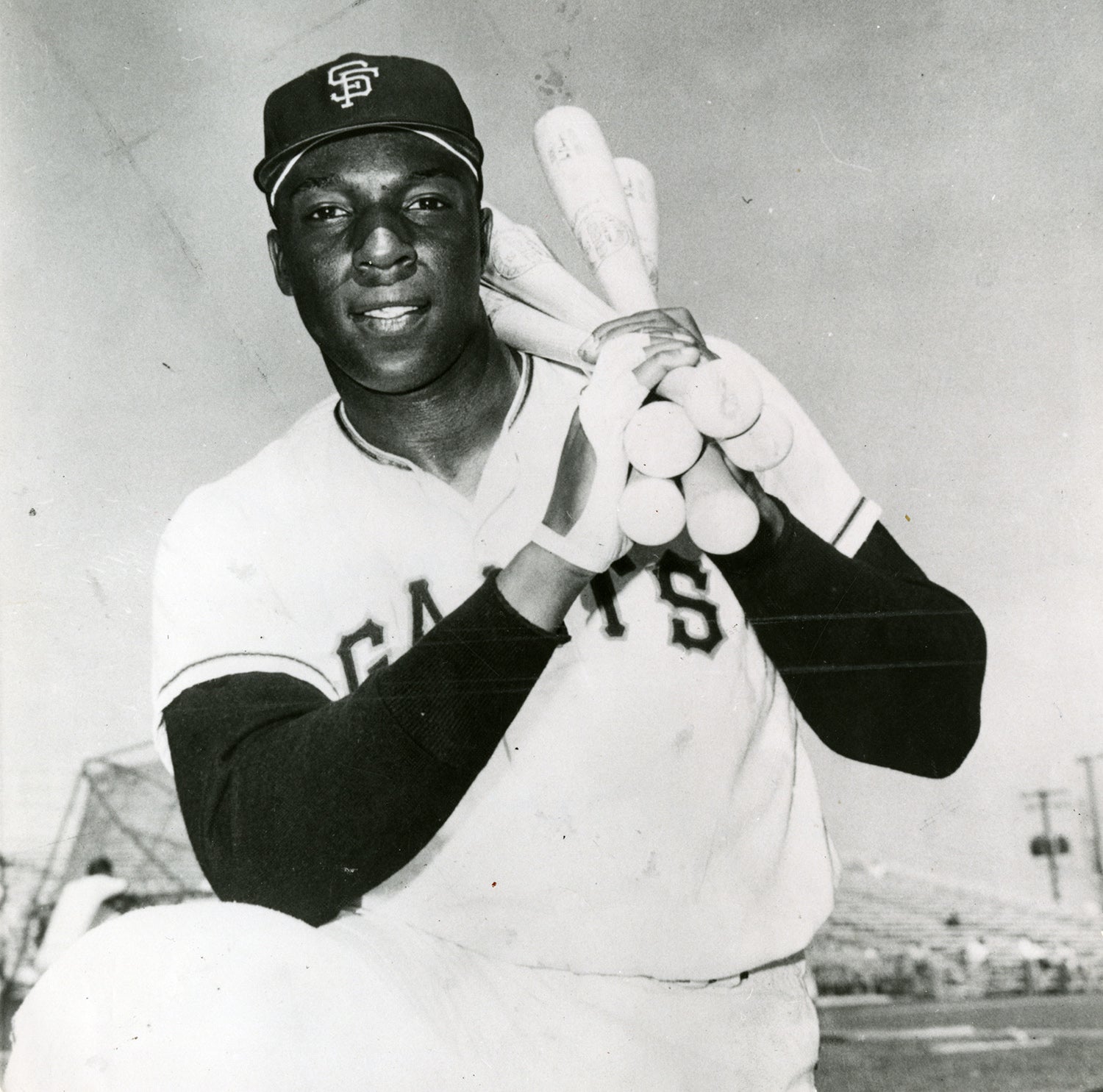

It is at the plate where Boog Powell is most remembered. That’s one of the reasons that his 1974 Topps card is one of my favorite depictions of Powell; it shows him near the end of one of his ferocious swings during a 1973 game at the original Yankee Stadium.

His massive body, with a good share of girth around the middle, is on full display on this card. We might also notice the subtle bending of his bat, something that is evident with hitters who generate a large degree of bat speed.

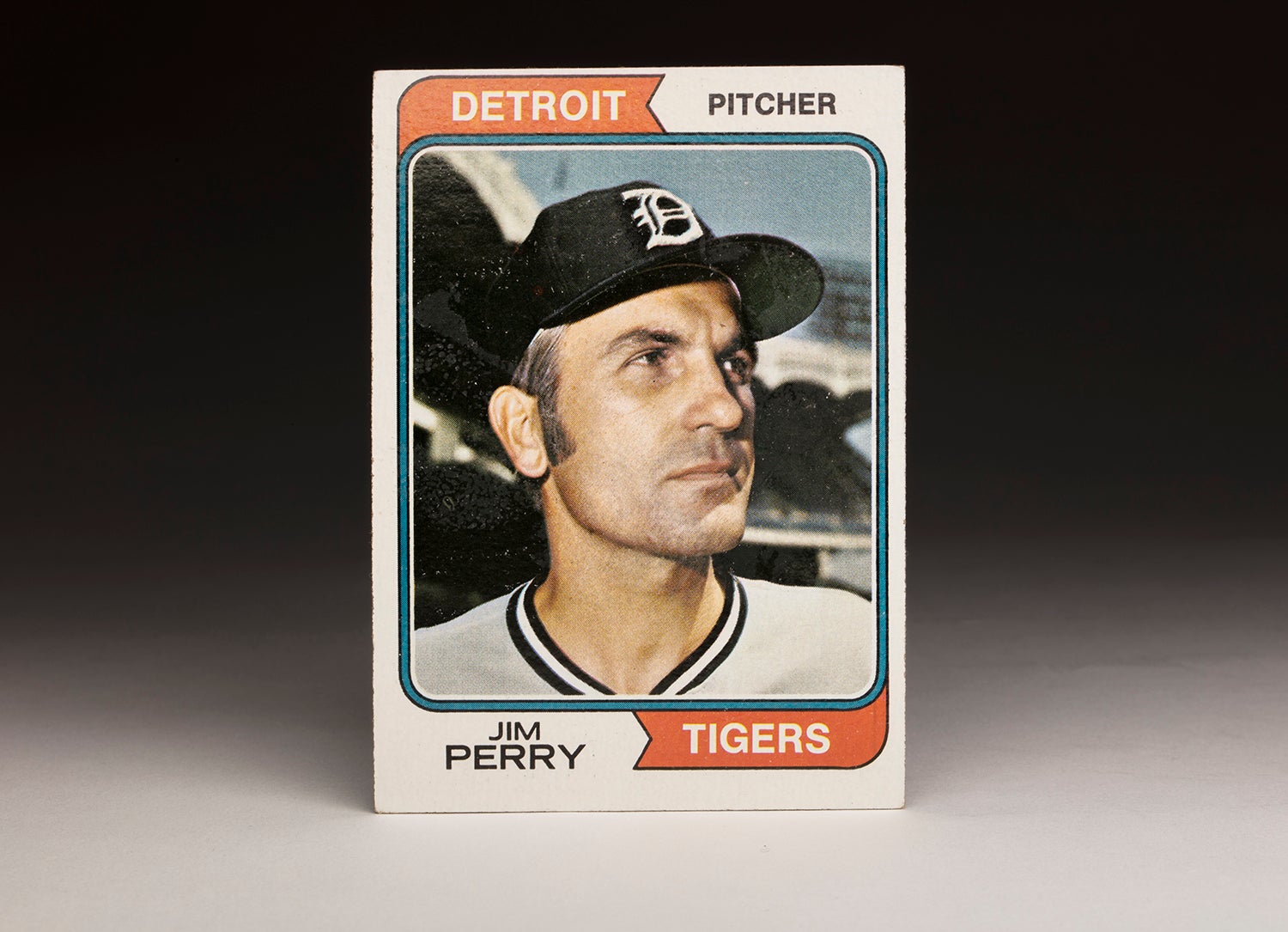

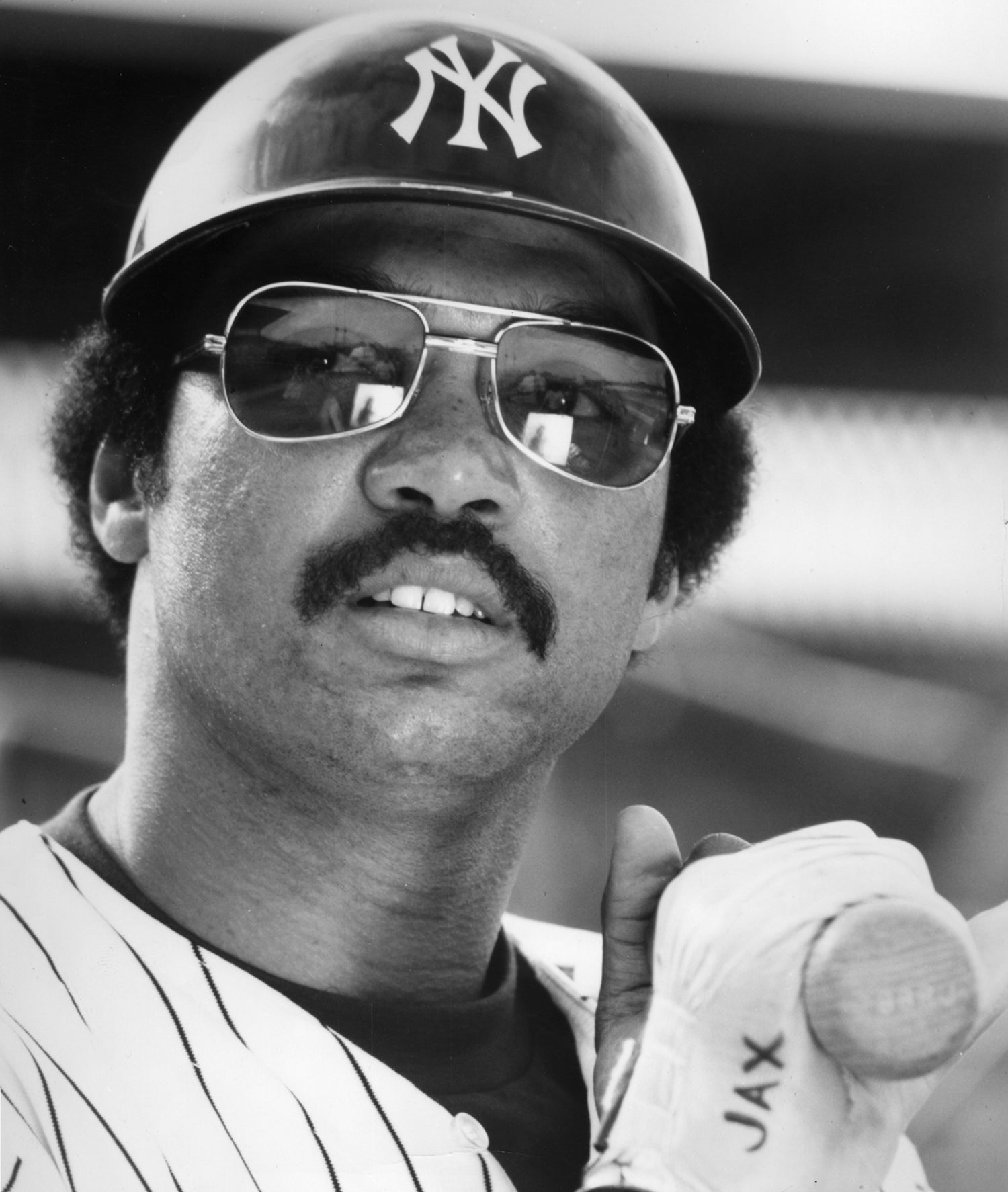

Other than Reggie Jackson, Willie McCovey and Willie Stargell, perhaps no left-handed hitter of that era was more feared than Powell. There were left-handed batters who were better all-around hitters than Powell, but few struck terror in the minds of pitchers (and first basemen and second basemen) the way that the hulking slugger did.

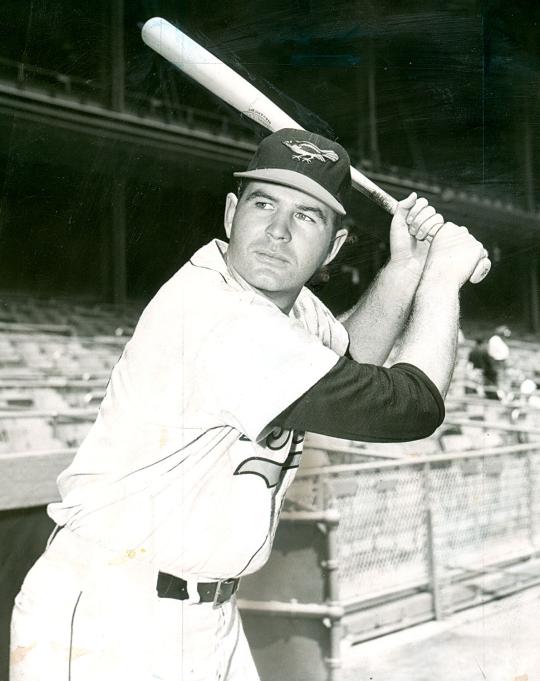

By conservative estimates, the 6-foot-4 Powell weighed 250 pounds, in an era when few players came close to approaching such dimensions. He swung hard, sometimes hitting pitches with so much force that it might have seemed possible the cover would fly off the ball. When it came to intimidating pitchers through immense size and sheer power, Powell stood near the top of the game.

Given his overgrown appearance, Powell looked like the kind of player who would have been clumsy and awkward in the field. But that was not the case, not at all. In actuality, Powell was graceful and sure-handed in fulfilling his fielding responsibilities at first base. While not a Gold Glover, he was a solid defender, one who nicely filled out a premier infield for the Baltimore Orioles.

Along with Dave Johnson (and then Bobby Grich) at second base, Mark Belanger at shortstop, and Hall of Famer Brooks Robinson (AKA “The Human Vacuum Cleaner”) at third base, the Orioles formed the kind of infield gauntlet that might have challenged even the likes of Clint Eastwood.

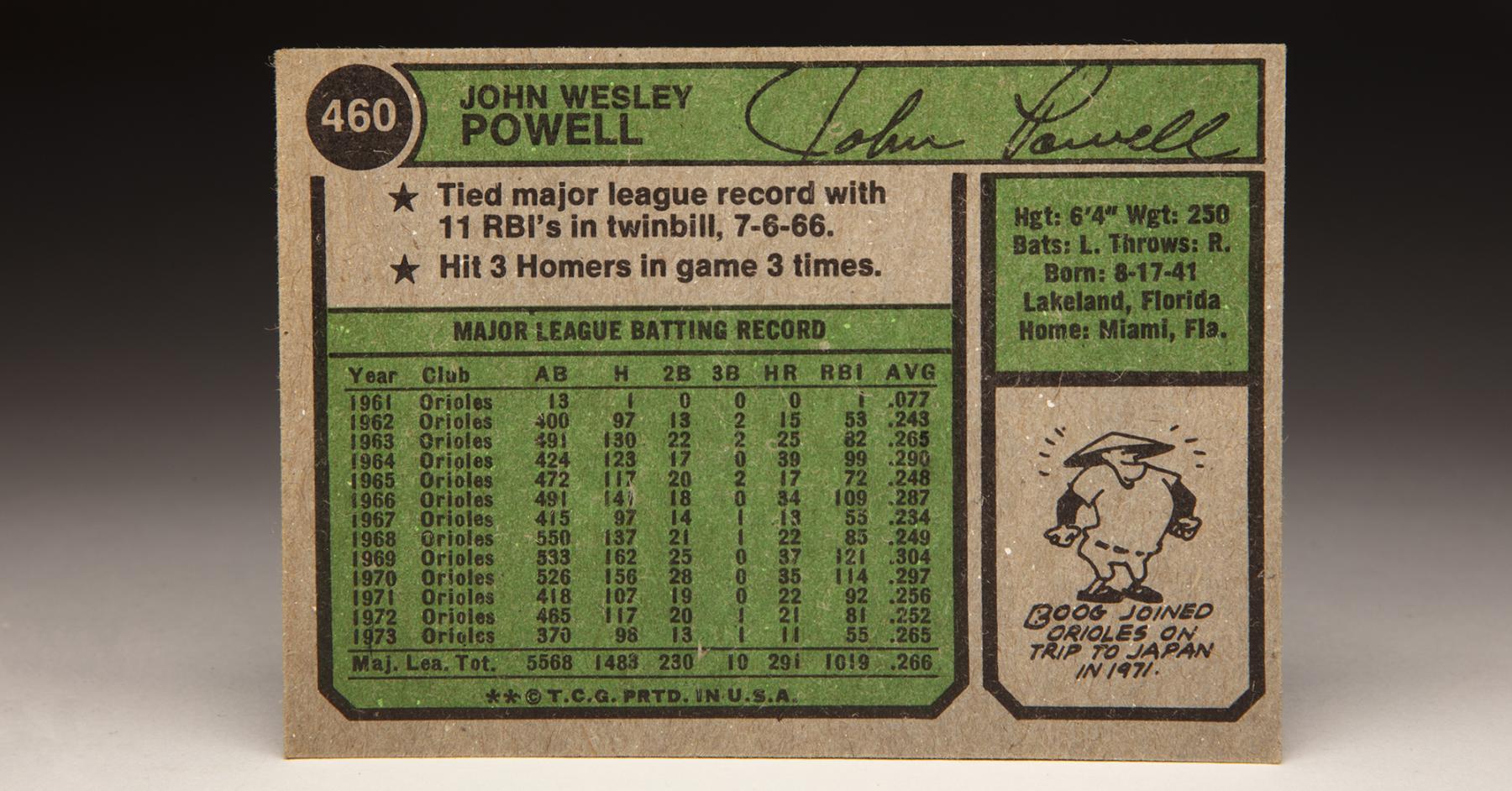

Other than his massive size, another noticeable feature of Powell’s Topps card is his name. Born John Wesley Powell, he was rarely listed as “John” on his Topps cards. Other than his 1962 rookie card, it was always “Boog.” That nickname came to him long before, at a very young age. As a child, the mischievous Powell sometimes misbehaved, leading his father to say, “What’s that little bugger up to now?” “Bugger” was eventually adapted and shortened to “Boog.” While a player with the name of John Powell might not be remembered so well, a slugger named Boog Powell becomes a completely different matter.

Powell’s venture into professional baseball began in 1959, when he bypassed a potential college career by signing with the Orioles out of high school. The organization assigned him to Bluefield of the Class D Appalachian League. Playing as an outfielder, Powell enjoyed his first taste of minor league pitching, hitting .351 with 14 home runs and an OPS of 1.018. The next summer, the Orioles moved him to first base and bumped him up to Class B, where he found similar success at the plate, hitting .312 with 13 home runs and 100 RBI.

Although Powell was only 19, the Orioles felt that he was ready to try Triple-A ball in 1961. Playing for the Rochester Red Wings, Powell continued to impress. A .321 batting average and 32 home runs convinced the organization to call him up to Baltimore at the end of the International League season.

Powell appeared in four late-season games for the Orioles and picked up only one hit in 13 at-bats, but that didn’t dissuade the organization from projecting him to be a key contributor in 1962. He not only made the Opening Day roster, but found himself in the starting lineup from Day One – batting third and playing left field.

With Jim Gentile firmly entrenched at first base, the O’s had no room for Powell to play regularly at that position. So they gave him plenty of playing time in left field, a plan that didn’t bother Powell in the slightest. “Jim Gentile would be a tough man to move,” Powell told the Sporting News. “I like to swing a bat, so it doesn’t matter where I play.”

Powell swung the bat respectably as a rookie, clubbing 15 home runs while compiling a .243 batting average. He might have done more offensive damage if not for a pair of injuries. A deep thigh bruise and a head injury caused by a beanball forced him to miss significant time, limiting him to 124 games.

An off-season spent in the Puerto Rican Winter League helped Powell immensely. He made adjustments by spreading out his feet more in the batter’s box and also being more patient, no longer prone to chasing as many pitches out of the strike zone. Those changes carried over to Spring Training of 1963. That spring, Powell’s hitting drew the highest of admiration from his manager, Billy Hitchcock. “He has a natural, firm, crisp stroke, a pleasure to watch,” Hitchcock told Doug Brown of the Sporting News. Team president Lee MacPhail also offered his praise.

“Powell has made more rapid progress in the minors than any player I’ve seen, except [Mickey] Mantle,” MacPhail informed Brown. Powell would continue the progress during the regular season, hitting .265 with 25 home runs and 49 walks.

In 1964, Powell’s offensive game exploded. Blasting 39 home runs, Powell led the American League with a remarkable .606 slugging percentage. He also finished 11th in the league in the MVP voting, but might have finished higher if not for a wrist injury that caused him to miss a full month of the season.

In 1965, O’s manager Hank Bauer moved Powell from left field, where he lacked speed and range, and switched him to first base. The move helped Powell defensively, but his hitting dipped unexpectedly. He batted only .248 and hit 17 home runs, fewer than half of his total from 1964. The Orioles believed that Powell’s conditioning was the culprit. At one point during the down season, Bauer fined Powell for being overweight.

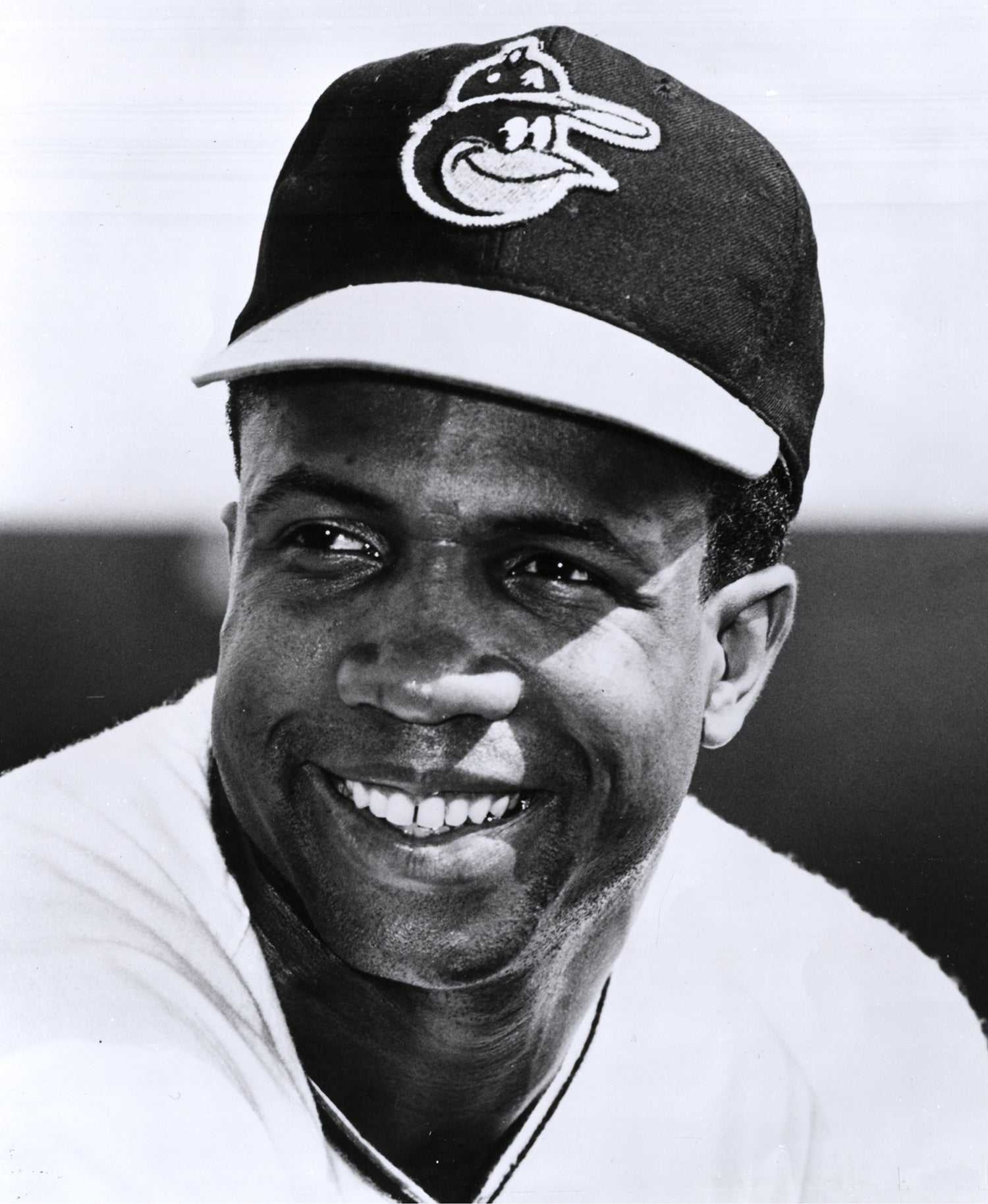

Then came the bounceback of 1966, a season that saw remarkable improvement for both Powell and the Orioles as a team. Powell hit .287, drew 67 walks, and belted 34 home runs. Thanks in part to a resurgent Powell and the vital trade acquisition of Frank Robinson, who would win the Triple Crown, the Orioles claimed the American League pennant. Powell and the O’s continued their rampage in the World Series. Boog batted .357 during Baltimore’s four-game sweep of the pitching-rich Los Angeles Dodgers.

Powell’s third-place finish in the American League MVP race also brought him some attention. With his large frame, blonde hair, and booming swing, Powell was becoming one of the more recognizable stars in the league. As much as the mammoth Powell looked like an intimidating behemoth swinging a large club, his personality ran in stark contrast to that physical image. He became known as the smiling giant, an affable player who was good-natured in the clubhouse and during games. At the ballpark, Powell liked to laugh and have fun. Similarly, he rarely argued with umpires and never seemed to lose his temper.

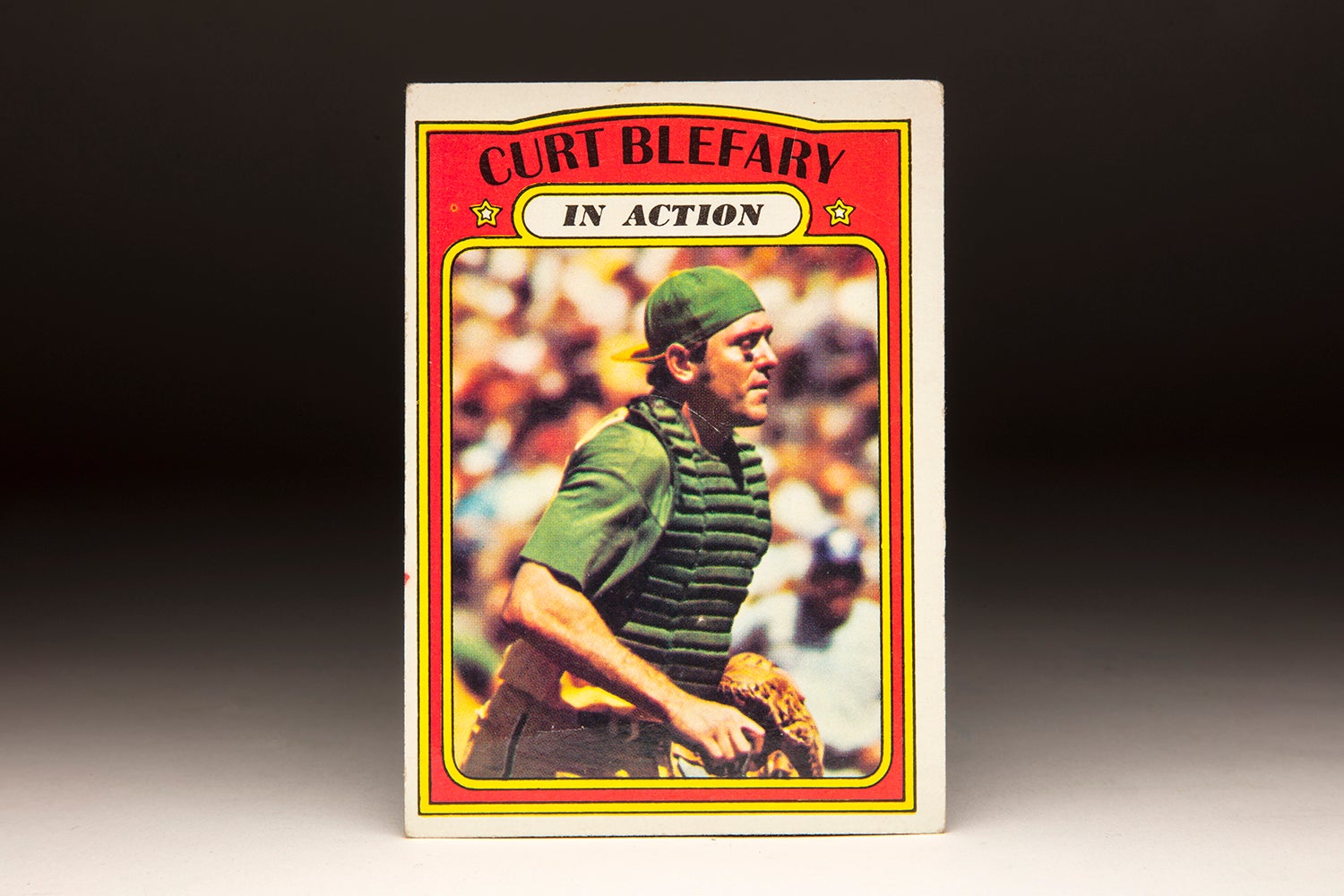

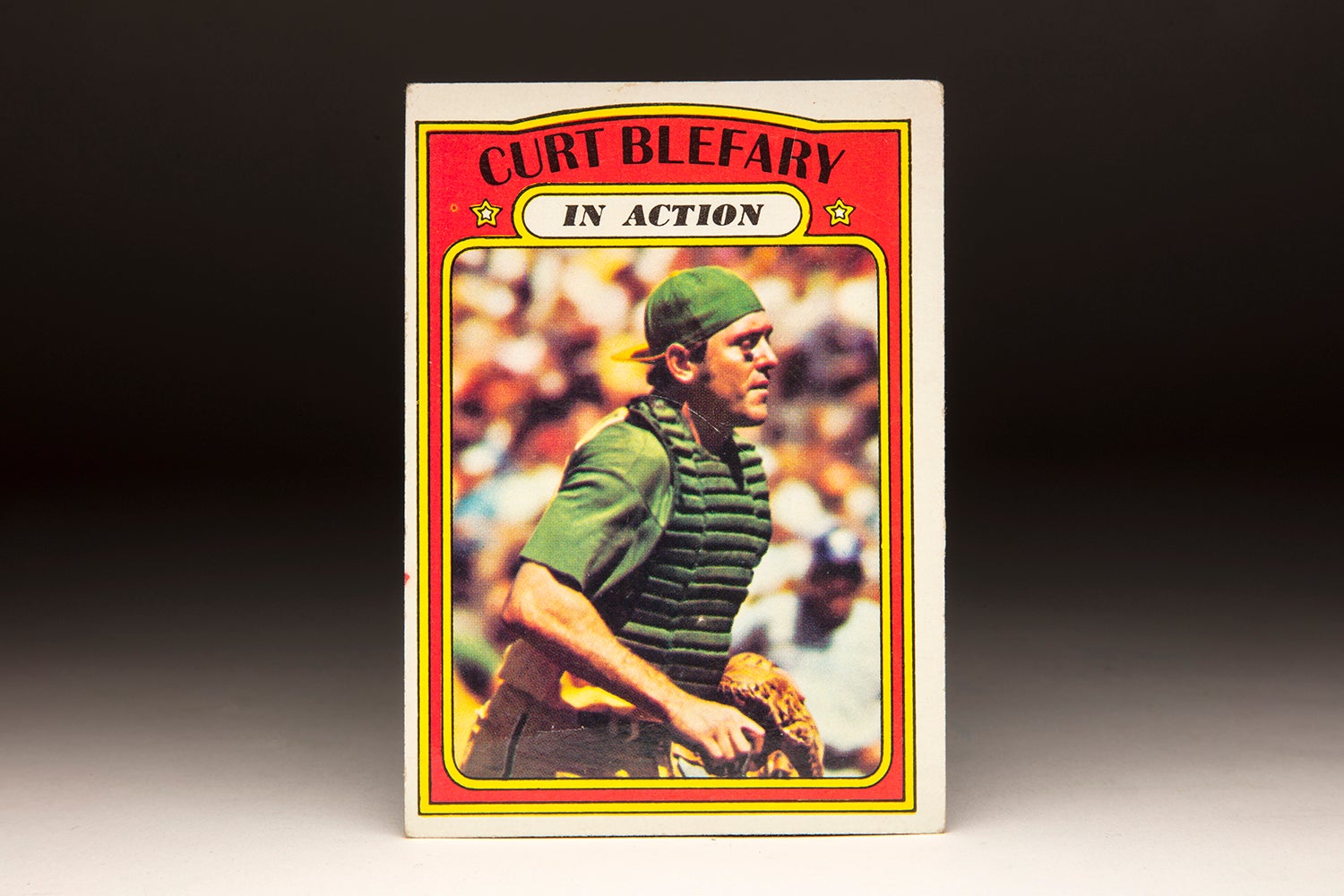

As well as Powell played in 1966, the following season fell to the other side of the spectrum. He slumped so badly that Bauer benched him for long stretches during the second half of the season, essentially replacing him with Curt Blefary. But in 1968, the season that became known as the “Year of the Pitcher,” Powell bounced back nicely. He made the All-Star team, while leading the Orioles in both home runs and RBI.

Powell performed even better in 1969. He batted .304, piled up 37 home runs, and earned a starting nod in the midseason All-Star Game. Along with Frank Robinson, Powell spearheaded the Orioles’ offense. The writers took notice, placing him second in the American League MVP race. Powell finished behind only Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew, who led the Minnesota Twins to the AL West title.

The one disappointment to the season occurred in the World Series. Powell batted .253 with no home runs, as the Orioles found themselves overwhelmed in five games by the upstart New York Mets.

Powell and the Orioles took their success a step further in 1970. The slugging first baseman enjoyed a career-best summer; he batted .297, drew 104 walks, powered 35 home runs, and compiled an OPS of .962. This time, he didn’t have to settle for second place in the MVP race. Powell won the award outright, finishing ahead of Tony Oliva, Killebrew and Carl Yastrzemski.

After sweeping the Twins in the ALCS, Powell and the Orioles completed the season with an epic effort in the World Series. Powell hit two home runs and compiled a 1.160 OPS against a very good Cincinnati Reds team. Taking the Series in five games, Powell and the Orioles captured their second title in the last five years.

The 1971 season proved more problematic for Powell. He began the season in a terrible slump, his average buried below .200 in mid-June. And then, just as he began to emerge from the hitting doldrums, he suffered a fracture of his right wrist. The injury forced him to miss two weeks.

Returning to action thereafter, he rebounded somewhat and finished the season with 22 home runs, but his overall numbers paled to those of 1970. The World Series brought more frustration. The Orioles blew a two games-to-none lead to Pittsburgh, as Powell struggled, managing only three singles in 27 at-bats.

In 1972, Powell again endured a poor start in April, May, and June. With his batting average floundering, he resorted to wearing glasses. They helped his vision, but not his hitting, so he stopped wearing the spectacles. He also tinkered with his batting stance and his position in the batter’s box. Powell hit better over the second half, with his final numbers looking very similar to his 1971 production.

Powell continued to play for the Orioles in 1973 and ’74, but he was now being platooned, his at-bats against southpaws severely decreased. The situation reached a valley late in 1974, when O’s manager Earl Weaver benched Powell in favor of the younger Enos Cabell. But Powell enjoyed one last hurrah for the Birds. Returning to the lineup in mid-September, Powell hit four home runs during the final two weeks of the season.

Trade rumors engulfed Powell that fall. At the 1974 Winter Meetings, the Orioles acquired slugging first baseman Lee May from the Houston Astros, a clear indication that Powell’s days in Baltimore were coming to an end. In February, the word became official: The Orioles traded Powell to the Cleveland Indians for catcher Dave Duncan and a minor league prospect.

The trade reunited Powell with Frank Robinson, his longtime teammate in Baltimore who had become the Indians’ manager. Robinson believed that Powell could still play and fill a void as the Indians’ everyday first baseman. While he admittedly looked odd wearing the Indians’ all-red uniforms – prompting Powell to say that he looked like “a giant blood clot” – he played well for Cleveland in 1975. He finished the season with a .297 batting average and 27 home runs, good enough to earn a few points in the American League MVP balloting.

Powell’s production made Robinson feel vindicated – and then some. “His batting average has been a pleasant surprise,” said Robinson in an interview that appeared in the Utica Observer-Dispatch. “We expected him to hit 20 to 25 home runs and knock in 70 to 80 runs, but the batting average has been an extra. We knew what he could do, and we knew he was better than those last two years in Baltimore.”

A good season in the books, Powell finally began to show his age (34) the following season. Injuries took a toll, more specifically a muscle tear in his right leg. Playing in only 95 games, he saw his batting average sink to .215 and his home run total fall to nine. Hoping that Powell could regain his health and his power, the Indians brought him back for Spring Training in 1977. But he continued to struggle, to the point that the Indians released him just before Opening Day.

Powell soon found work with the Los Angeles Dodgers. Yet, the team already had an All-Star first baseman in Steve Garvey, leaving Powell as a glorified pinch-hitter. He accrued only 53 plate appearances with the Dodgers before receiving his release on Aug. 31, thereby denying him another shot at the postseason. The Dodgers’ decision to cut him loose ended his major league career.

Powell’s jovial personality only helped him during his post-playing days. Along with other ex-ballplayers like Marv Throneberry and umpires like Jim Honochick, he became a staple of the popular Miller Lite television commercials.

In 1978, he and Honochick teamed up for the first in a series of memorable spots. In the first commercial, the two are seen facing a camera while standing in a crowded bar. When Honochick has trouble reading the label on his Miller Lite bottle, Powell lends him his glasses. Honochick, now wearing the new specs, looks up, finally realizing who he’s been talking to all along. “Hey, you’re Boog Powell!” the retired umpire says excitedly, prompting a laugh from the burly slugger. Honochick would re-use the line in later commercials, even when Powell was not present.

Continuing to do commercials and make promotional appearances for Miller Lite into the late-1980s, Powell also ran a marina in Key West, Fla., where he resided. In the 1990s, he opened up “Boog’s Barbeque,” a food stand located outside of Camden Yards in Baltimore. As Orioles fans can attest, the personable Powell regularly signs autographs and talks baseball with fans, especially the younger ones who never saw him play. They all learn about Boog.

A strange circumstance has led to even more recognition for Powell. In 2016, a young outfield prospect named Boog Powell broke into the big leagues with the Oakland Athletics. No relation to the former slugger Boog, the younger Powell’s presence has stirred up memories for older fans, while making younger fans aware of the original carrier of the name.

All these years later, Boog Powell remains an ambassador of the game. Even a late 1990s bout with cancer has done little to dampen Powell’s spirit. Now in his late 70s, Powell has retained his outgoing nature and charming demeanor, along with his sense of humor. He can’t bend a bat anymore, but when it comes to having fun at the ballpark, John Wesley Powell hasn’t lost a step.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

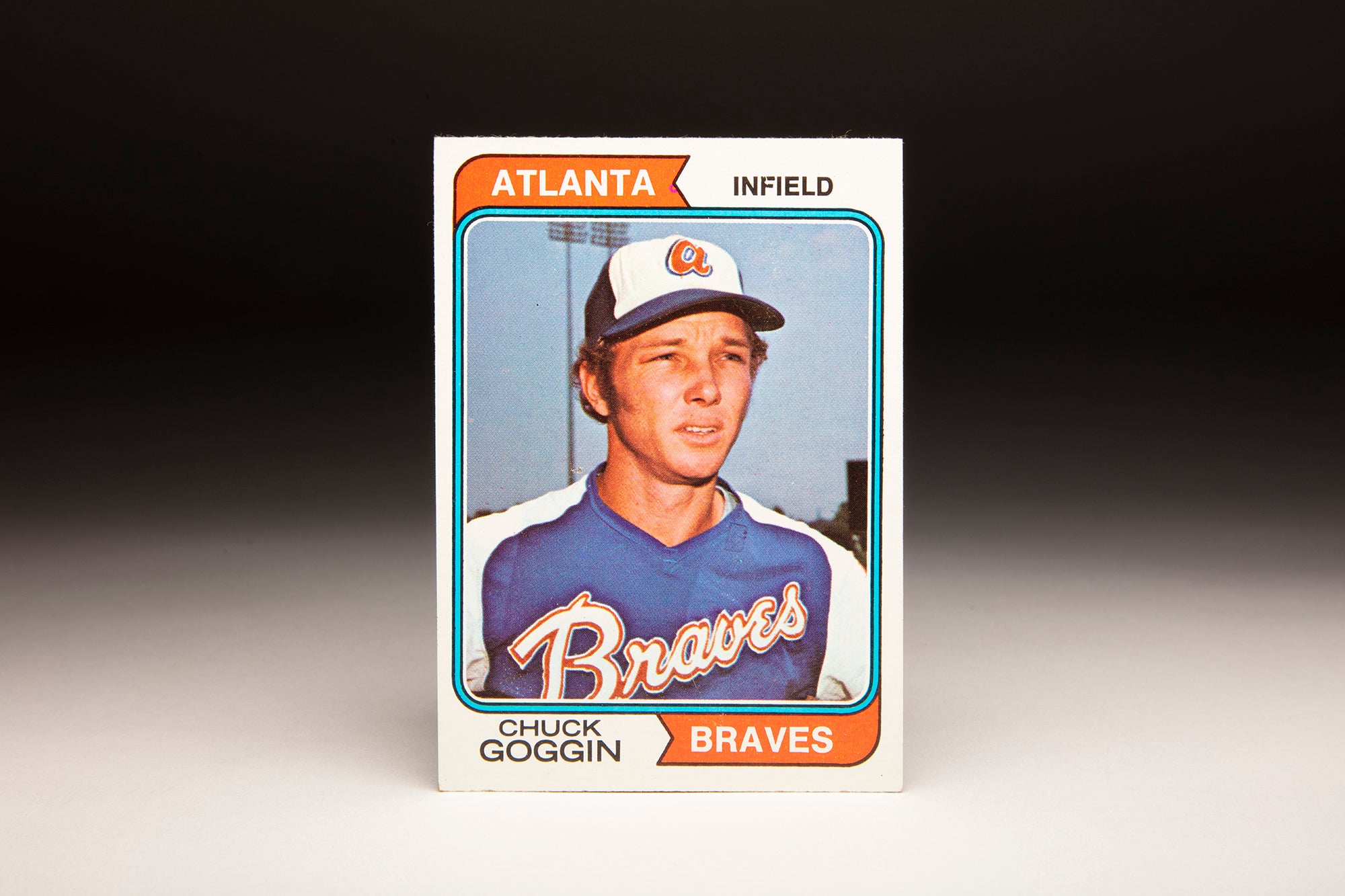

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Chuck Goggin

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Curt Blefary

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Chuck Goggin