- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1974 Topps Chuck Goggin

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Chuck Goggin

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

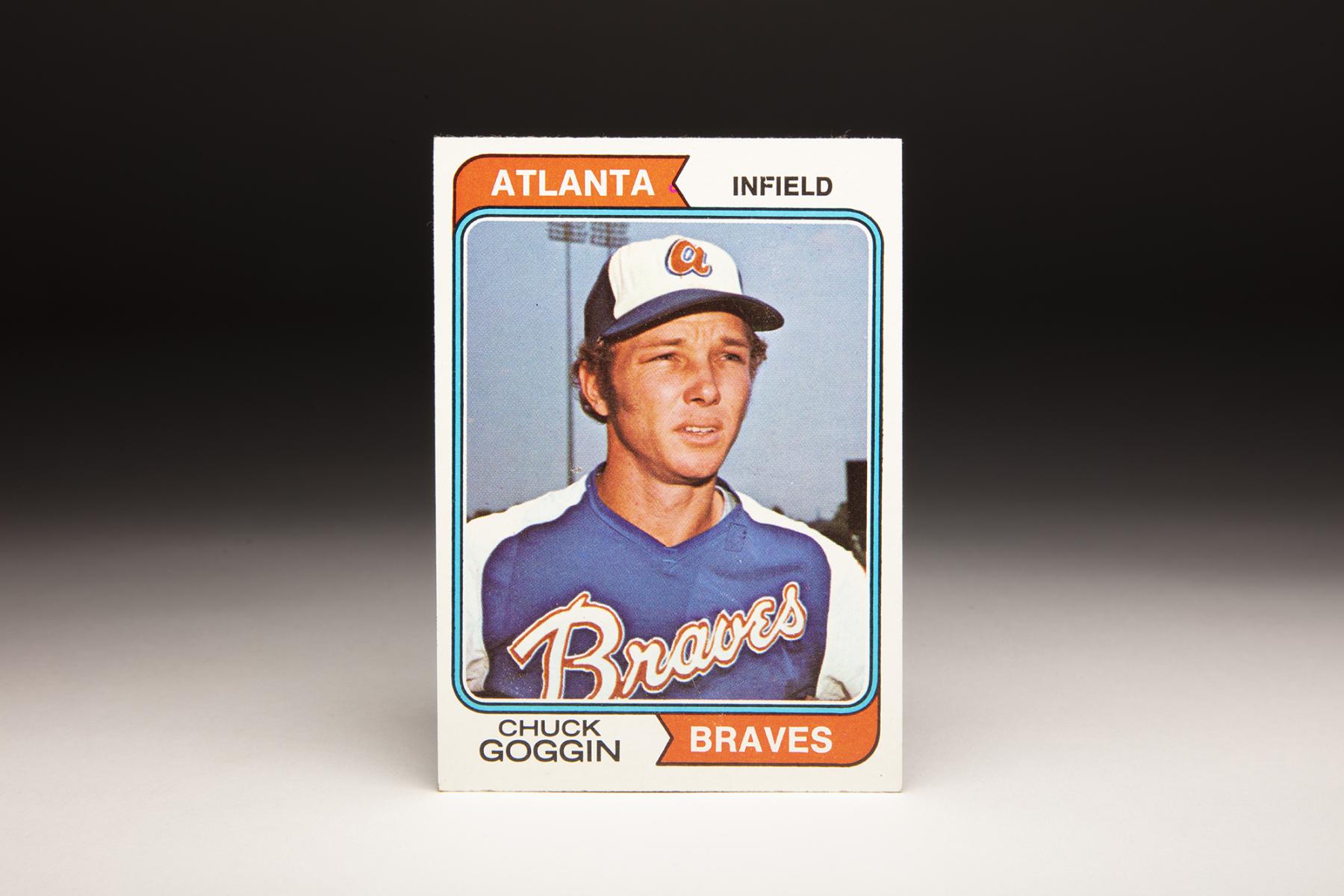

The one time that Topps featured Chuck Goggin on a baseball card, the photographer captured him wearing the two-toned blue and white polyester uniforms of the Atlanta Braves. The Braves had only recently switched to those colors, after wearing a more traditional pinstriped look in the preceding years.

On this 1974 Topps card, Goggin is modeling the Braves’ road uniform, which featured blue jerseys with white on the sleeves and shoulders, and “Braves” written out in large white script across the chest. The caps displayed the reverse color scheme – white in the front and blue on the sides with a large red “A” in the middle. Those uniforms fit right into the gaudy era of 1970s polyester, a trend that was making its way through both major leagues.

At the time, young know-it-all fans like me and my friends poked fun at those threads for being too loud and flashy, but in retrospect, those Braves colors have achieved some cult popularity. In fact, the Braves have brought those caps back in recent years for “throwback” days and nights at their ballpark. Those caps, identified with the era in which Hank Aaron broke the career home run record, have become favorites for both old and young alike.

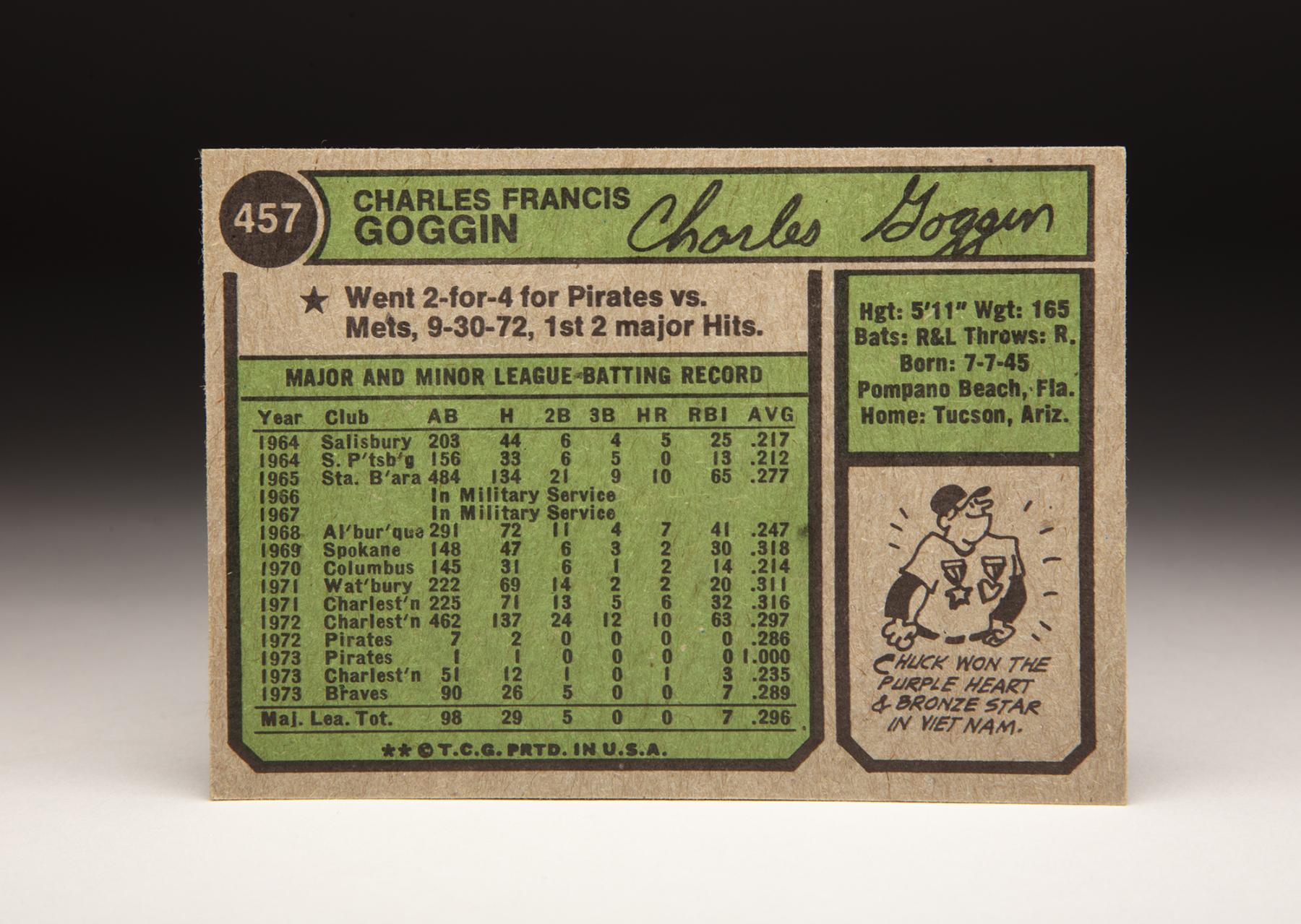

Those caps and uniforms were vastly different from the uniform that Goggin wore several years earlier. Prior to making the major leagues, he served in the U.S. Marines during the Vietnam War. That part of the story is headlined on the back of the ’74 Topps card, which features a small cartoon of Goggin wearing medals on his chest. Under the cartoon, the following words appear: “Chuck won the Purple Heart and Bronze Star in Viet Nam.”

Like a number of other ballplayers from the 1960s and 70s, Goggin lost part of his major league career to Vietnam, doing so without complaint or much recognition. Goggin spent two years in the military during the war, even though he wasn’t even supposed to have been drafted.

Along with some other minor leaguers in the Los Angeles Dodgers’ system, he had initially attempted to enlist in the Army Reserves, but an Army official told him that wasn’t necessary because he would never be drafted. Why? The official noticed a large scar on his knee, the result of a recent surgery. Goggin had torn cartilage in the knee while playing minor league ball. Due to the ensuing surgery, the Army classified him as 4-F, disqualifying him from service in the military.

That would all come to a sudden reversal at the end of the 1965 season. Without any explanation, the U.S. Military crossed out Goggin’s 4-F classification, changed his status to 1-A, and sent him his official draft notice, with orders to report to Marine boot camp in February of 1966. So Goggin traveled to Parris Island and then underwent infantry training at Camp Lejeune, full knowing that he would be assigned to duty in Vietnam. In July, he received his orders to report to Southeast Asia.

Now a full-fledged member of the Marine Corps, Goggin served as an infantry rifleman. “The fact that I was a baseball player impressed nobody,” Goggin told Steve Wulf of ESPN.com. “They hadn’t heard of me.” Goggin later transitioned to radio operator, one of the most dangerous jobs anyone could have during the Vietnam War. Goggin had to carry a large radio that weighed 30 pounds and featured a large antenna, which made him an easy target for the enemy.

On March, 2 1967, Goggin was traveling with Lima Company’s 3rd battalion when it engaged a North Vietnamese regiment in battle. Goggin was part of a band of soldiers nicknamed “Ripley’s Raiders,” a reference to its leader, Captain John Ripley, a legendary figure in Vietnam history. Within the first few minutes of a horrific battle, Lima’s platoon commander, platoon sergeant and first squad leader were all killed. Given those casualties, Captain Ripley made Goggin the platoon commander. It was a responsibility that was usually reserved for commissioned officers and not for draftees.

That didn’t seem to affect Goggin, who ably led the troops through the rest of the battle. At the start of the encounter, Ripley’s Raiders had numbered 250. By the end of the day, only 15 men were left standing; the rest had been injured or killed. Despite the low numbers of able-bodied men, Ripley’s Raiders won the battle. Goggin’s leadership during the crisis so impressed Ripley that the captain decided to keep him in his new position as platoon commander.

During his time in Vietnam, Goggin was wounded several times. The last time occurred later in 1967, when he unknowingly stepped onto a landmine. “I heard this thing explode and could feel the shock hit me,” Goggin told the Sporting News. “It lifted me up in the air eight to ten feet. The first thing I could remember thinking was, ‘Damn, I’ve stepped on a landmine.’ I wasn’t too worried because I could tell immediately it didn’t hit me any place where it could kill me. It was one of those quick things when everything rushes through your mind at once.”

Goggin’s description minimizes the severity of what happened. His body was thrown roughly eight to 10 feet into the air; his back and legs were covered with a total of 14 shrapnel wounds. Thankfully, the wounds were not life-threatening, but they were serious enough to put him out of action, forcing him to recover for several weeks aboard a floating hospital. For his bravery and service, Goggin earned both a Purple Heart and the Bronze Star.

Once Goggin healed from his wounds, he returned to his unit and continued to command his platoon. On Aug. 20, 1967, his 13-month tour of duty came to an end. Still a member of the Dodgers’ organization, he reported to Spring Training in February of 1968. Fully recovered from his encounter with the landmine, Goggin played well in Grapefruit League exhibition games, convincing the Dodgers to assign him to their affiliate at Double-A Albuquerque. There he hit .247 while hitting seven home runs and stealing 14 bases. While those seemed like modest numbers, they were somewhat remarkable given the trauma that his body had endured in Vietnam.

After the season, the versatile infielder reported to the Instructional League, where he learned to switch-hit under the encouragement of his manager, who happened to be Tommy Lasorda.

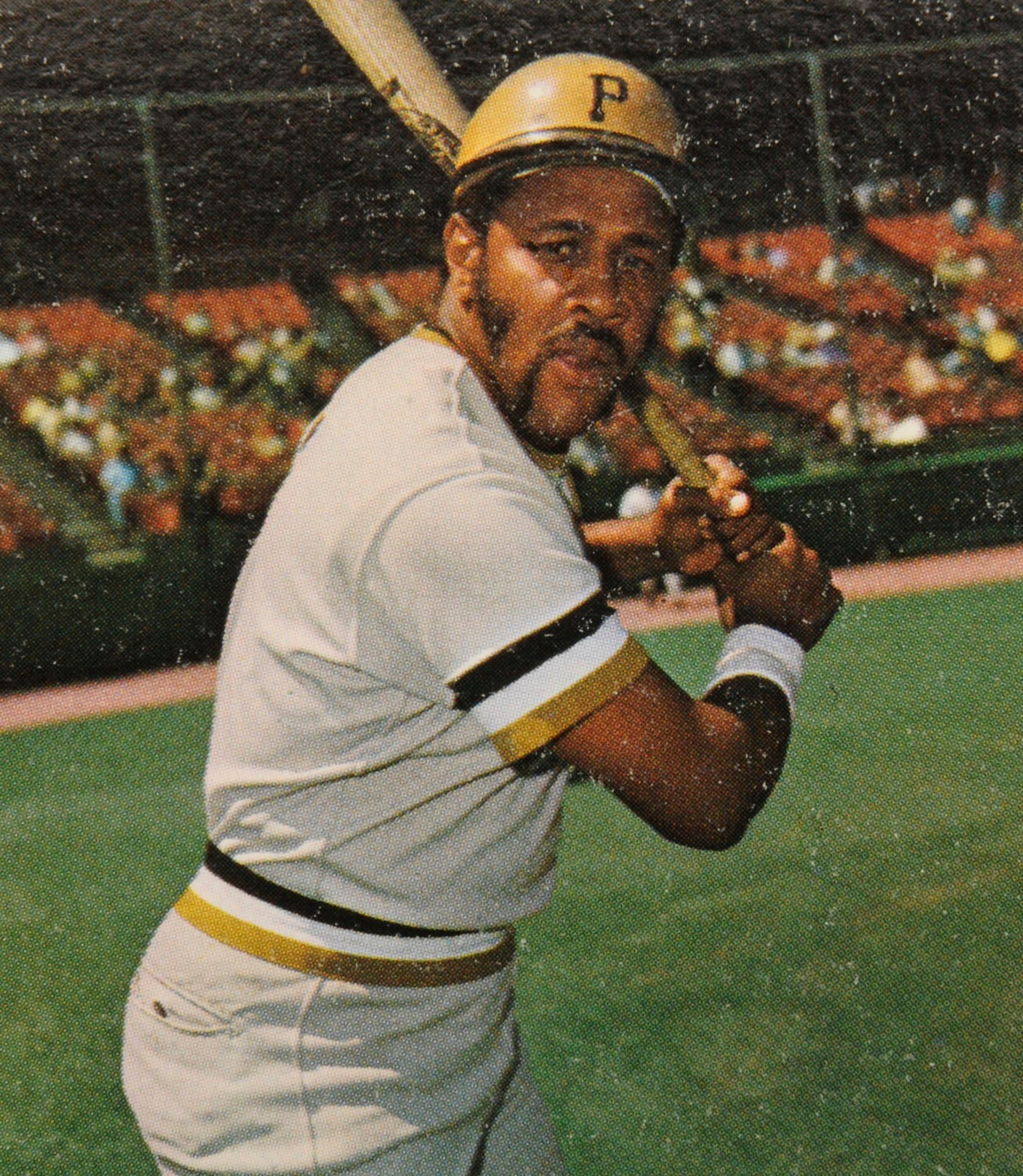

Following a 13-month tour of duty in Vietnam, Chuck Goggin traveled to Dodgers' Spring Training in February of 1968. After that season Goggin reported to the Instructional League, where he learned to switch hit with the instruction of manager Tommy Lasorda. (Rich Pilling/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Previously a right-handed hitter, Goggin took well to the switch-hitting experiment, raising his average to .336, but then came another setback: A broken ankle suffered while trying to steal second base. It was an extreme fracture, with his ankle bent 180 degrees from its usual position. The doctor who operated on Goggin predicted that he would never play again.

Given the latest obstacle, no one could have blamed Goggin for quitting and giving up his dream of making a major league roster. But the war veteran took the latest injury in stride. He slowly rehabilitated the ankle and returned to action by the middle of the 1969 season.

Shortly after coming back, the Dodgers traded Goggin, sending him and another minor leaguer to the Pittsburgh Pirates for future Hall of Fame right-hander Jim Bunning.

The Pirates liked Goggin, but felt that he was suited to be a utility player and little more. Prior to the 1971 season, Goggin challenged Bucs farm director Harding “Pete” Peterson to make him an everyday catcher at Double-A as a way of expediting his ascent to Pittsburgh. Peterson liked the idea, but had to agree to a condition from Goggin: The Pirates needed to buy him two catcher’s mitts.

Goggin took well to the catching experiment. He also hit .311 at Double-A Waterbury and made the Eastern League All-Star team. The Pirates then rewarded Goggin with a promotion to Triple-A Charleston, where he lifted his average to .316.

Goggin returned to Charleston in 1972 and continued to excel, hitting .297 with an OPS of .853 and finishing second in the International League MVP Award balloting (behind future big league star Dwight Evans). After the Triple-A season came to an end, the Pirate gave Goggin the news he wanted to hear: A call-up to Pittsburgh. On Sept. 8, he made his major league debut. Summoned as a pinch-hitter for relief pitcher Dave Giusti, Goggin worked out a walk in his first big league plate appearance.

Over the balance of the season, Goggin played sparingly, but did reach base three times in eight plate appearances. He then reported to Spring Training in 1973 and made the Pirates’ Opening Day roster as a backup catcher and utility infielder. But the Pirates, a deep and talented team, struggled to find playing time for Goggin. Over the first month of the season, he appeared in only one game. Not knowing what to do with Goggin, the Pirates decided to move on, selling the utility man to the Atlanta Braves.

While with the Braves, Goggin received more playing time. He became an important part of the Braves’ bench brigade, which received some notoriety in 1973. The Braves’ bench included such veterans as Dick Dietz, an aging catcher/first baseman who had once started for the San Francisco Giants; and Frank Tepedino, a former first base prospect with the New York Yankees.

Dietz, Tepedino and Goggin all played brilliantly in limited playing time for the Braves. Collectively, this group of castoffs became known as “F-Troop,” a reference to the popular 1960s television show that centered on a military unit of misfits at the mythical Fort Courage.

Goggin filled in at five positions (including the most demanding positions of catcher and shortstop) while compiling an on-base percentage of .350. One of the highlights to his season came on Aug. 5, when he a made a fine play on a line drive at second base, helping to preserve Phil Niekro’s no-hitter against the San Diego Padres.

Based on his versatility and productivity, Goggin seemed like a cinch to make Atlanta’s roster in 1974, but the Braves felt they needed a fulltime, defensive-minded catcher more than a jack-of-all-trades. During Spring Training, the Braves traded Goggin to the Boston Red Sox for Vic Correll, a catcher with strong receiving skills.

In so doing, the Braves made Goggin’s 1974 Topps card outdated practically from its first day of issue. Goggin would not make the Red Sox’ Opening Day roster. He hurt his back while warming up in the outfield one day, started the season on the disabled list, and then received a demotion to Triple-A. The back injury affected Goggin’s play at Pawtucket, but the Red Sox called him up in September, along with two other players named Fred Lynn and Jim Rice.

While Lynn and Rice would eventually become stars, Goggin would appear in only two games for the Sox. Goggin’s two-game cameo in Boston marked the end of his career as a player. Despite his versatility and ability to reach base, Goggin could not find work with another team.

Still, he remained in baseball, becoming a minor league manager for the Braves and Cincinnati Reds. He later found work as a skipper in the Mexican Pacific League, leading Navojoa to the Pacific Coast League title. His players in Mexico included a young outfielder named Rickey Henderson.

When his time in Mexico ended, Goggin left baseball and pursued a completely different line of work. He went into local politics in his hometown of Nashville, Tenn. His political associations in Nashville brought him in contact with President Ronald Reagan, who appointed him a U.S marshal for the Middle District of Tennessee, a position that he held from 1983 to 1995.

After his retirement, Goggin concentrated his efforts on building a memorial to the members of Ripley’s Raiders who died in combat. Dedicated in March of 2012, the memorial is housed at the Marine Corps Museum in Triangle, Va., and honors the men from Lima Company who died in 1967.

While Goggin appeared in only 73 games over the span of three seasons, he has accrued a list of accomplishments and experiences rarely associated with a major league player. Along with Roy Gleason, he is one of only two players who was wounded in combat during Vietnam. And he is one of only a few players to become a U.S. marshal after his playing days. There is little doubt that Chuck Goggin deserves to be called an American hero.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

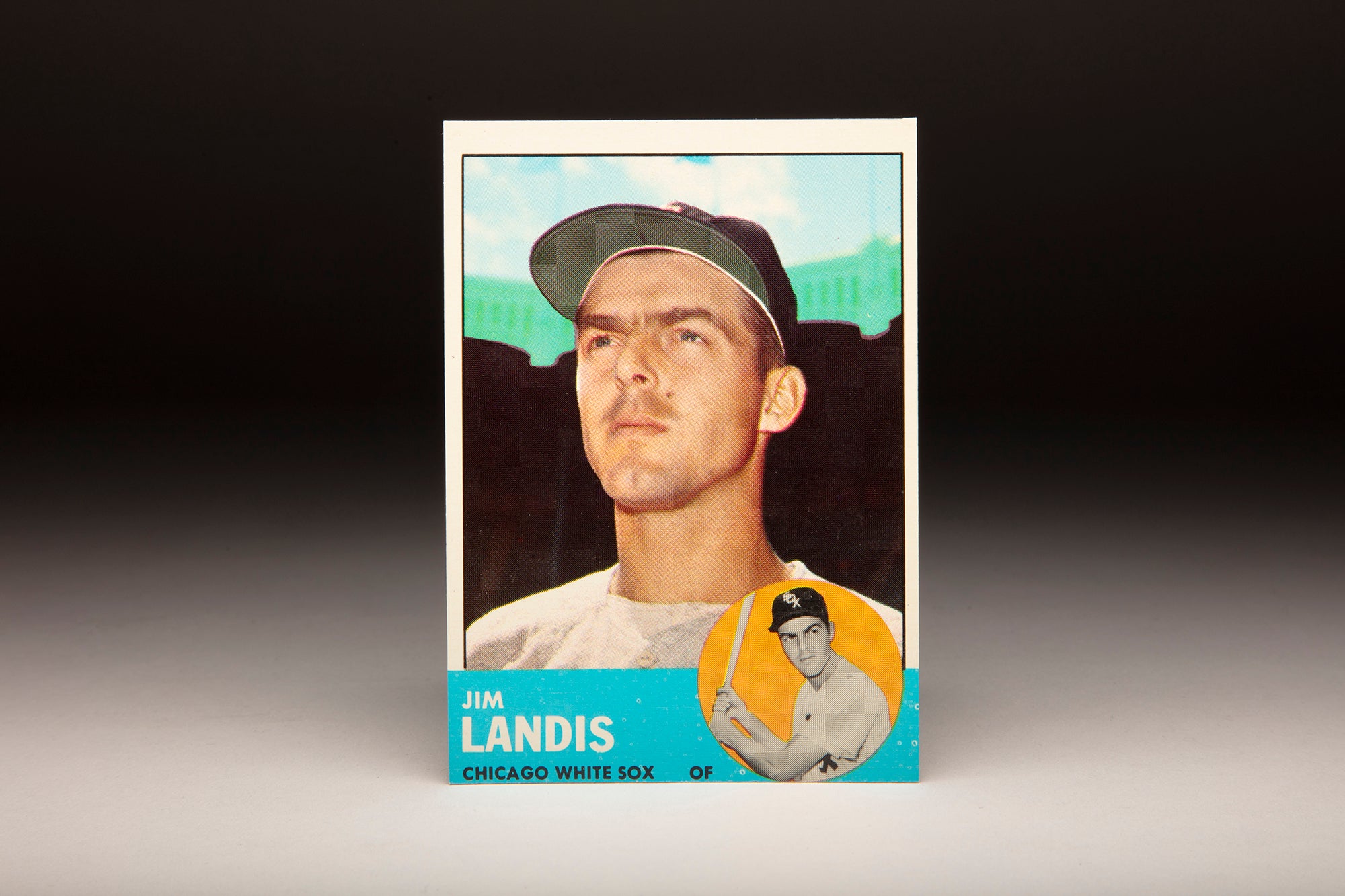

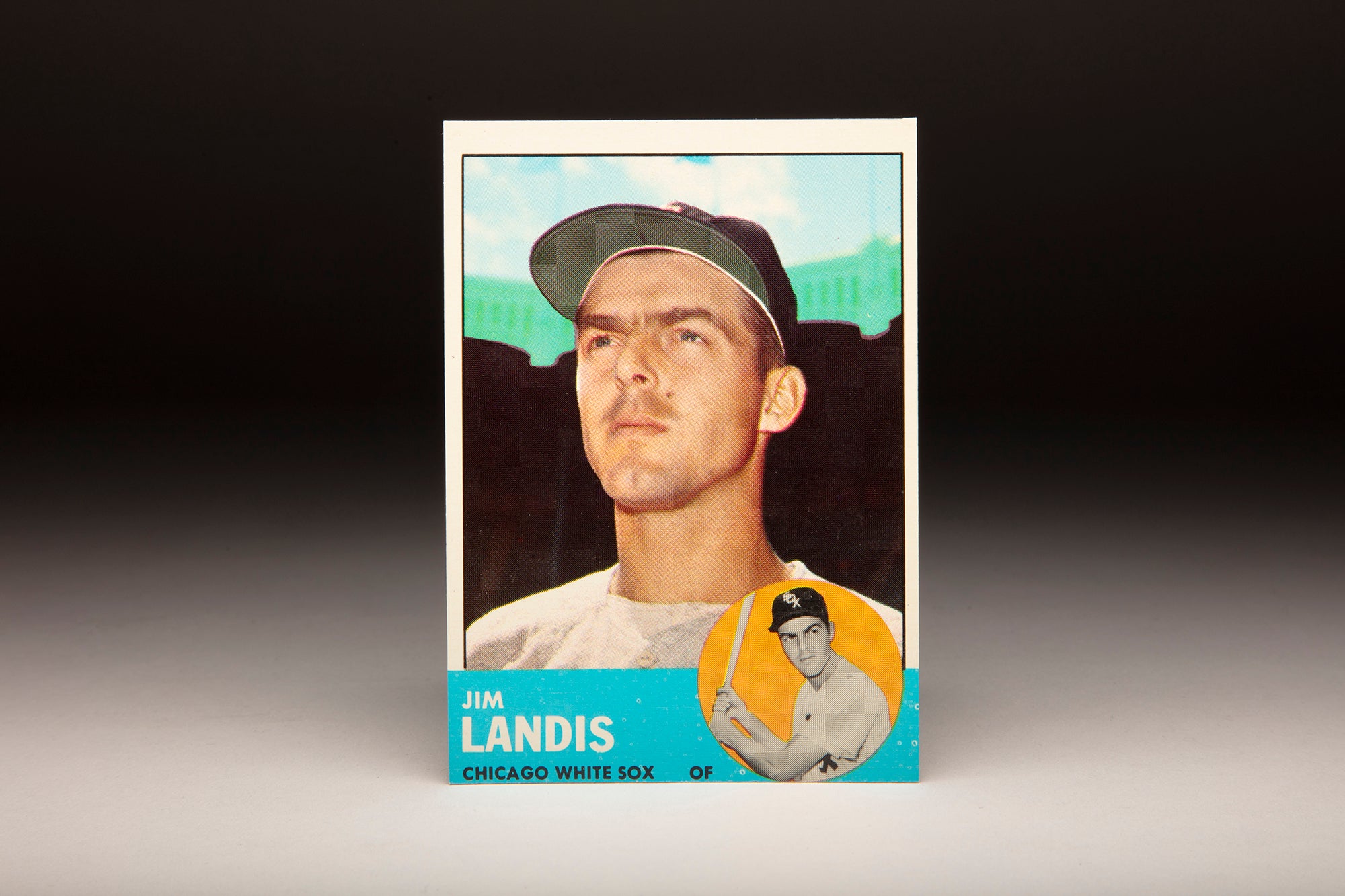

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Jim Landis

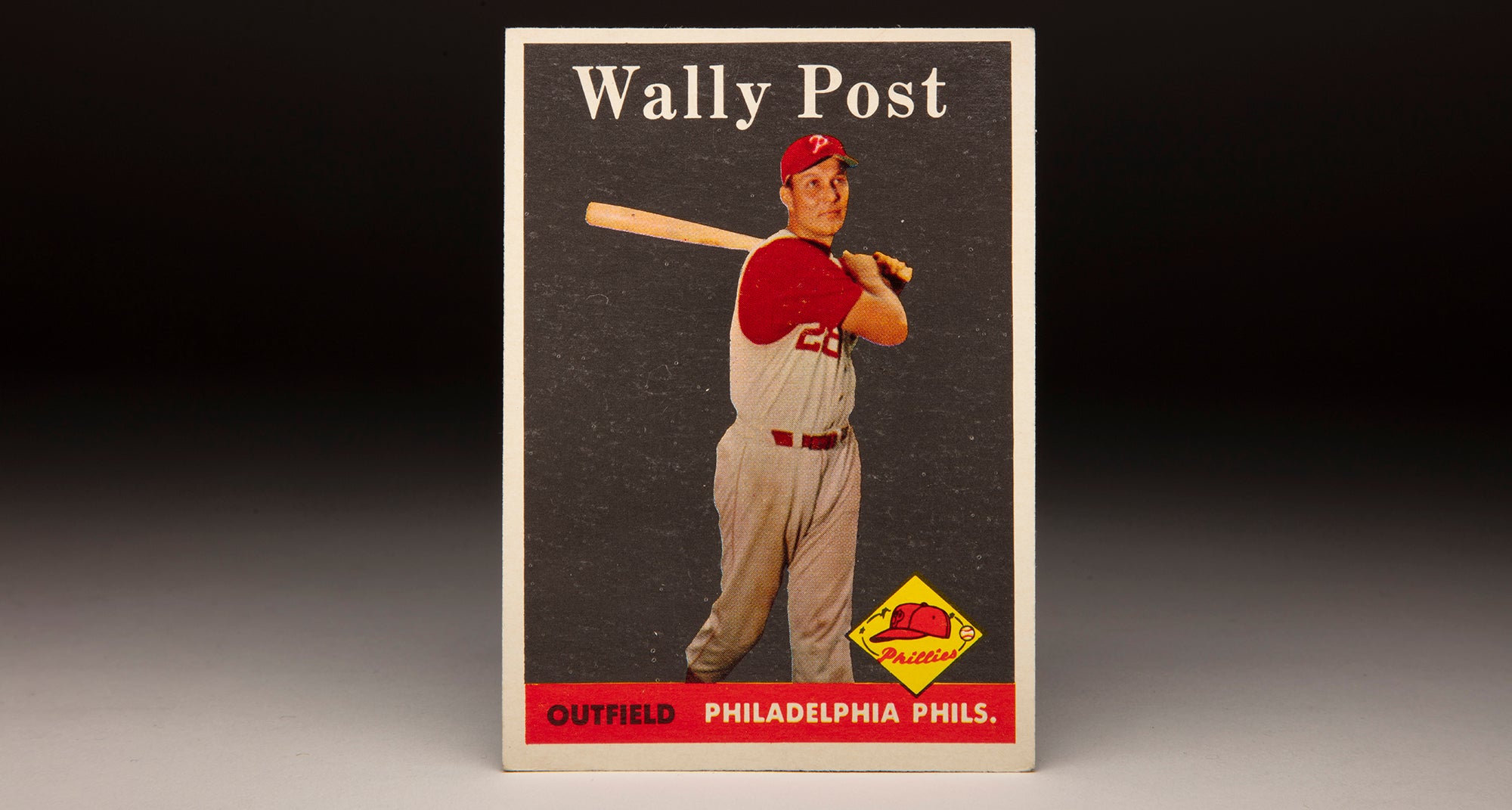

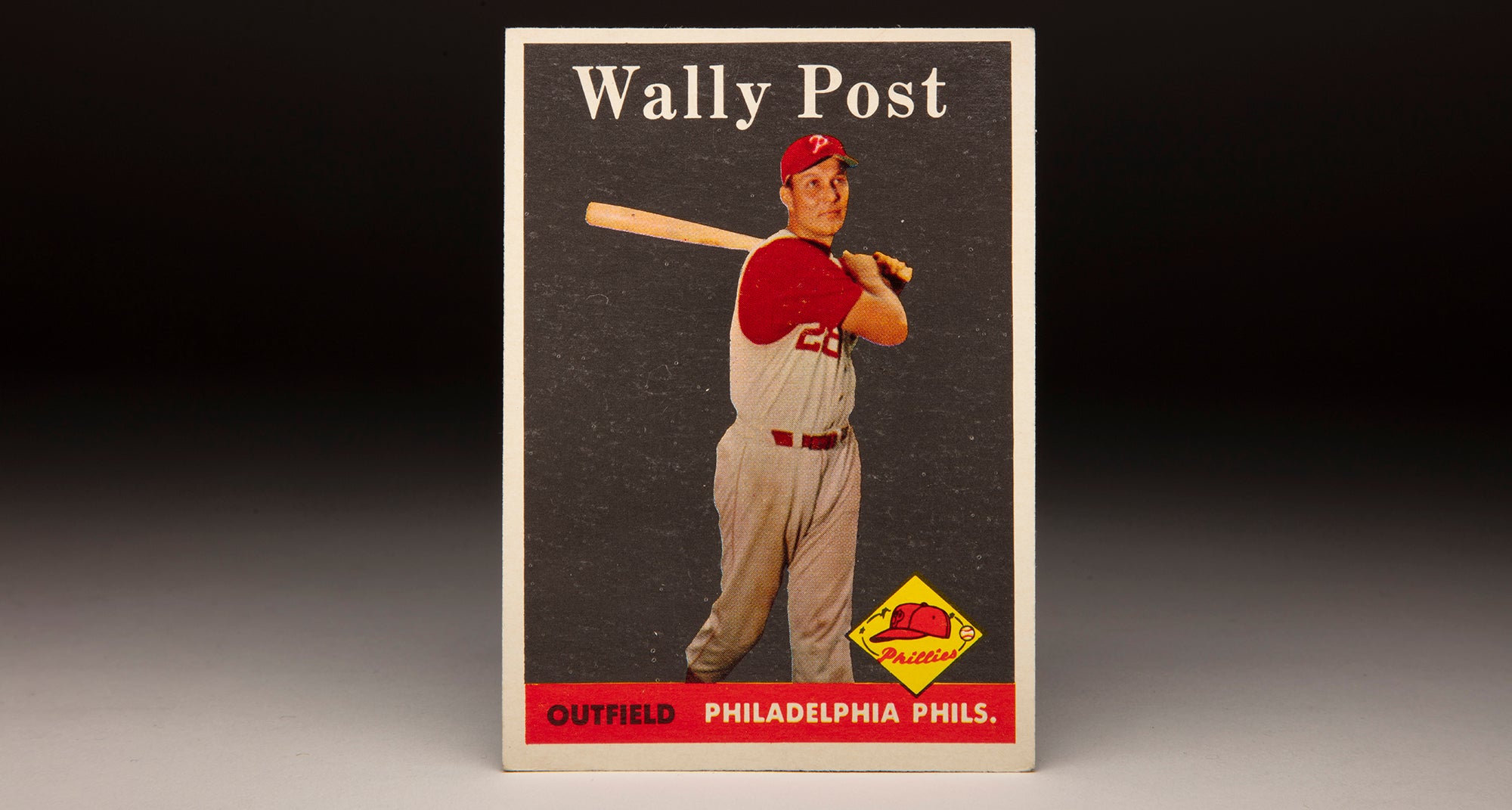

#CardCorner: 1958 Topps Wally Post

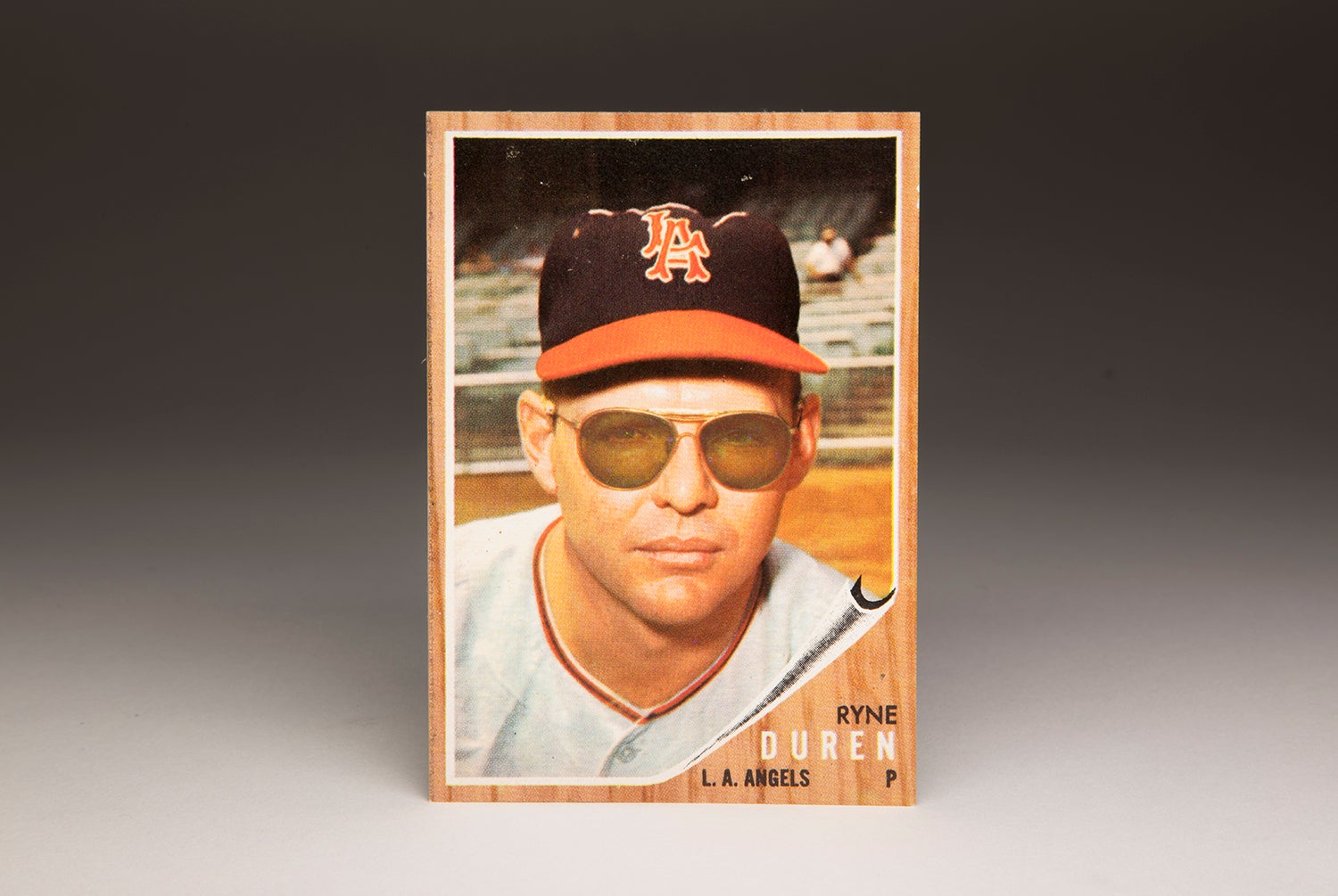

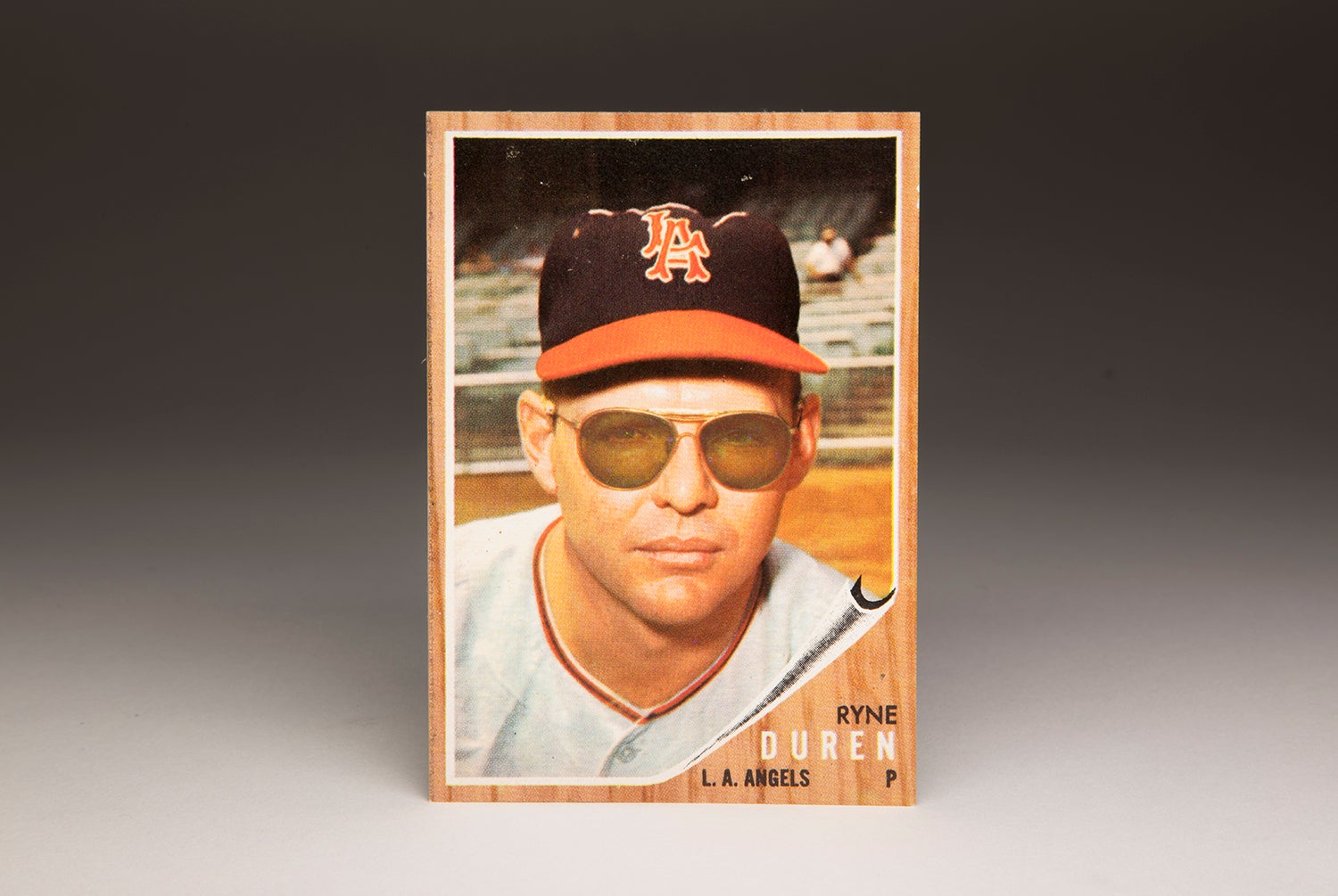

#CardCorner: 1962 Topps Ryne Duren

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Jim Landis

#CardCorner: 1958 Topps Wally Post