- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1962 Topps Ryne Duren

#CardCorner: 1962 Topps Ryne Duren

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

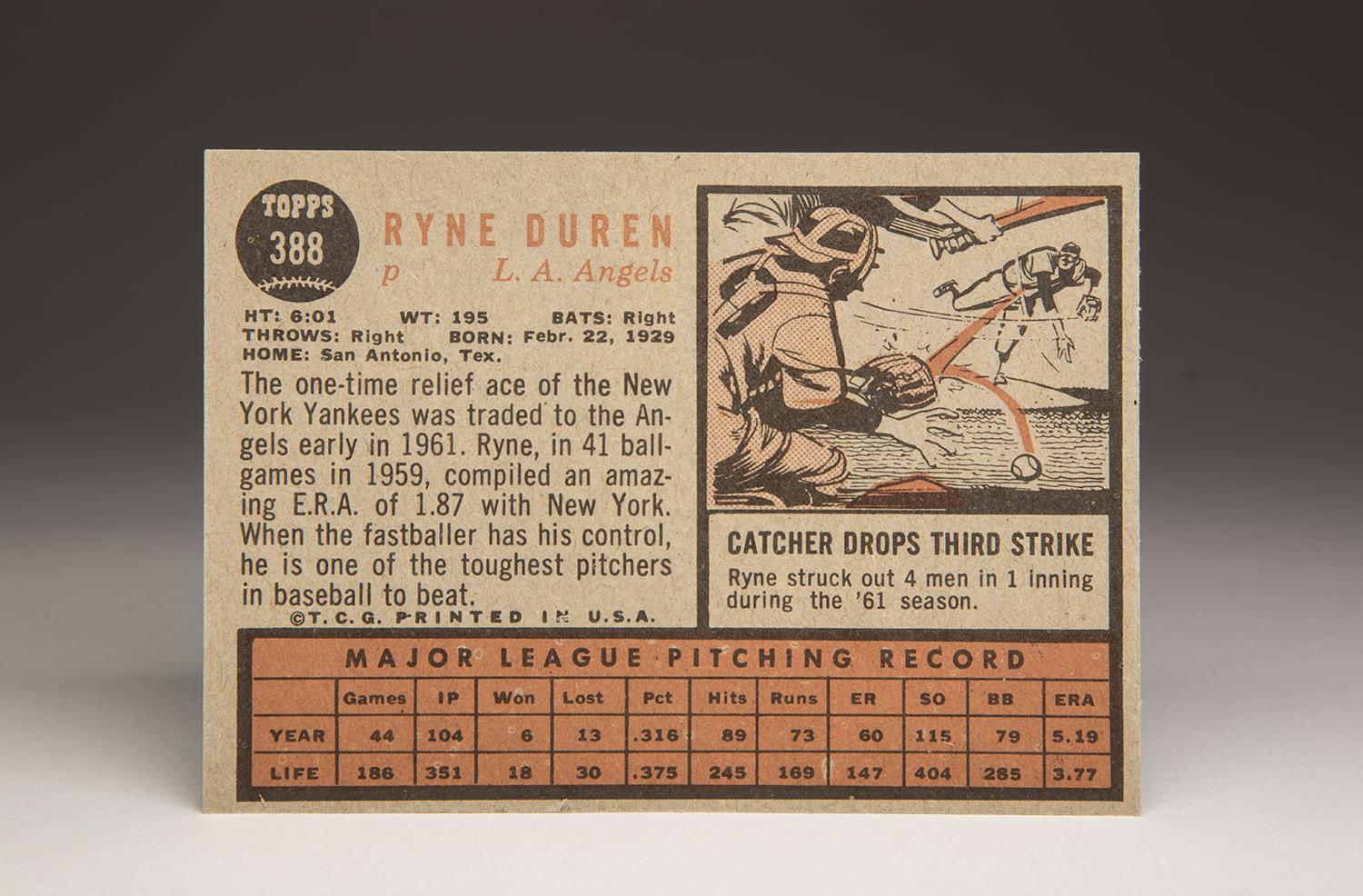

One look at Ryne Duren’s 1962 Topps card gives you the feeling that you’ve just been pulled over on a California highway by a stern-looking trooper wearing dark glasses, a hardened man in no mood to hear your justification for going 10 miles above the speed limit. I imagine that this is exactly how many American League batters felt when they had to step in against Duren during the late innings.

The Duren card takes hold of you, from the murkiness of his glasses to the unflinching expression of his face as he glares into the Topps camera. That it’s a cloudy, gray day only adds to the feeling of intimidation that comes with a look at Duren’s face. The card is also well-executed in its presentation and production. The colors on Duren’s Los Angeles Angels cap are striking, with the two-tone shades of dark blue and red richly presented on this Topps canvas. It’s a clear photo, too, very easy to make out the details of the interlocking “LA” on the crown of the cap, along with an indication of the lined halo that made those Angels caps so distinctive.

In so many ways, this is a visually appealing card, made stronger by its inclusion in the iconic 1962 Topps set. For Topps, this set represented a departure from the traditional white borders of the cards that the company had almost always used. With this set, Topps introduced its famed wood borders, which became a huge hit with collectors in the 1960s. Topps not only featured a thin, wood-grained border that stretched the length of the card, but also expertly peeled back the photo in the lower right-hand corner, so as to allow more of the wood background to show through while also providing space for the name of the player and his team. Thanks to the brilliant design, the 1962 set registered with every kind of collector, from children to adults.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In some ways, Duren’s career was as fascinating as his card. He pitched in high school, but was so wild that no professional scouts took interest in him. He began working in a factory, but maintained a connection to baseball by playing weekends in a local sandlot league. It was there that he was spotted by a bird dog scout for the St. Louis Browns, a man named Ernie Randolf. Based on the recommendation or Randolf, who took note of Duren’s powerful right arm, the Browns signed him in 1949, giving him a bonus of $500.

Duren could throw as hard as anyone in the Browns’ system, but a lack of control prevented him from climbing the minor league ladder quickly. Pitching in Dayton one year, he walked 194 batters in 198 innings. Duren’s difficulty in throwing strikes were exacerbated by his poor eyesight, which had been caused by a childhood bout with rheumatic fever. The terrible lighting in many minor league ballparks only exacerbated the problem. Both interlocking factors made it difficult for him to see the catcher’s signs or his target at home plate.

The Browns arranged for Duren to see an eye doctor, who actually suggested that the young right-hander give up the game. That seemed like an extreme reaction to Duren, who wanted to continue pitching. Instead of retiring, Duren was fitted with extremely thick glasses, so thick that they were likened to the glass on bottles of Coca Cola. Later on, Duren turned to tinted glasses, the kind that we see in full bloom on his 1962 Topps card.

By the time he finally reached the major leagues in 1954, the Browns no longer existed; they had moved to Baltimore and become the Orioles. Duren made his debut on Sept. 25, in what turned out to be a less-than-stellar performance. He gave up three hits and two runs in two innings, giving him an ERA of 9.00 for the outing – and the season.

Duren went back to the minor leagues for the next two summers. In the spring of 1955, Orioles manager Paul Richards, in a desperate attempt to improve Duren’s control, instructed his young right-hander to become a breaking ball pitcher, and emphasize throwing his curveball and slider. That dubious plan resulted in a sore arm, limiting Duren to 90 innings of minor league work. Returning to health in 1956, he greatly improved his control – the result of working with his minor league manager, Lefty O’Doul. Pitching in the Pacific Coast League, Duren walked 87 batters in 205 innings. His ERA also rose above 4.00, but that was partly attributable to the hitter-friendly conditions of the PCL.

Although Duren exhibited progress with his control, the Orioles decided that he would not be a part of their future. In late September, they sent him to the Kanas City Athletics as the player to be named later from an earlier transaction. The trade allowed him to join an organization that needed pitching in the worst way.

The A’s looked at Duren as both a starter and reliever, but his control remained a problem. He appeared in 14 games, with his ERA rising to 5.27. At the June 15th trading deadline, the A’s gave up on the 28-year-old right-hander. They sent him, Harry “Suitcase” Simpson and Jim Pisoni to the New York Yankees for a package that included infielders Woodie Held and Billy Martin and right-hander Ralph Terry.

The Yankees sent Duren right to Triple-A Denver. In his very first game for Denver, Duren pitched in one of the games of a doubleheader and fired a seven-inning no-hitter. He would continue to pitch well at Denver over the balance of the season, even though his longstanding problem with alcohol abuse persisted. Duren had been drinking for years, but he was now beginning to act more erratically and rowdily. At one point in 1957, Denver manager Ralph Houk had to bail Duren out of prison after he became involved in a barroom fight, resulting in charges of disorderly conduct and resisting arrest.

Even though Duren was 29 when he reported to Spring Training in 1958, he was still technically regarded as a rookie, given his lack of service time during previous stints with the Orioles and A’s. Upon the suggestion of Houk, who had just been promoted to the major league coaching staff, the Yankees converted Duren from a starter to a fulltime reliever. Houk realized that Duren’s slider and curve ball were merely average pitches. As a reliever, Duren could concentrate efforts on throwing his fastball, far and away his best pitch.

Houk’s suggestion turned out to be brilliant. Avoiding any kind of alcohol-related incidents that spring, Duren not only made the Yankees’ Opening Day roster, but he soon became the most trusted reliever of manager Casey Stengel. Over the first two months of the season, Duren picked up seven saves and completely dominated American League hitters.

During the 1958 season, Duren’s high-powered fastball took on added respect. While warming up in between innings one day, he accidentally unleashed a fastball that sailed over his catcher’s head. The fans and attending media took notice, as did batters on the opposing team. So Duren decided to add an intentional wild throw to his warm-up arsenal, as a way of intimidating hitters. Duren didn’t do it every time, but every once in a while he fired a warmup pitch over his catcher’s head and into the backstop screen behind home plate. It was a not-so-subtle way of warning hitters not to dig in during their at-bats against Duren. Those wild warm-up tosses, along with his constant squinting at the catcher’s signals, drove hitters into nervous distraction.

Duren’s dominant relief pitching helped the Yankees win the pennant in 1958, but the season did not come and go without controversy. In mid-September, after the Yankees clinched the American League title, Duren partied a bit too intensely. He became involved in an altercation with Houk, in which he shoved Houk’s cigar into his face. Houk responded by swinging his hand at Duren, cutting him with his World Series ring. The incident, witnessed by New York sportswriter Leonard Schechter, became a national story, while offering a hint at Duren’s ongoing problems with alcohol.

While the story proved to be a distraction, it did not prevent the Yankees from winning the World Series that fall. Duren pitched beautifully in three Series games, capping off a season in which he finished second in the Rookie of the Year balloting and earned some consideration for American League MVP. Just like that, with a league-leading 19 saves and a sterling ERA of 2.02, the well-traveled Duren had become a full-fledged star.

In 1959, Duren managed to pitch even better for the Yankees. He lowered his ERA to 1.88 and struck out 96 batters in 76 innings. For the second straight summer, Duren made the All-Star team. He pitched well through late September, when he fell and broke a bone in his wrist, ending his season a bit prematurely.

With two peak seasons in his pocket, Duren seemed primed for a third. But in the spring of 1960, he was bothered by pain in his right knee. Despite the soreness, he pitched well in his first five appearances, but then started to lose his control of the strike zone. Beset by increasing wildness, Duren lost his fireman role by June. Becoming depressed over his poor pitching, Duren began to drink more. His behavior became more erratic, a concern to both teammates and the front office.

In spite of his poor season, the Yankees reached the World Series in 1960. Duren appeared in two World Series games, but was completely bypassed by Stengel in Game 7 – a heartbreaking loss suffered at the hands of Bill Mazeroski and the Pittsburgh Pirates.

After the Series, the Yankees fired Stengel and replaced him with Houk. Nicknamed “The Major” because of his military background, Houk expressed a desire to instill discipline in the clubhouse. He also told the media that Duren’s drinking needed to be monitored. During Spring Training, Duren ran afoul of Houk, incurring a fine for “detrimental behavior.” Not surprisingly, Houk soon replaced Duren as the Yankee fireman with Bill Stafford.

In April and May, Duren made five appearances in middle relief. On May 8, Duren’s Yankee career came to an end; the front office dealt him to the expansion Angels as part of a five-man trade that brought outfielder Bob Cerv to the Bronx.

At first, the Angels used Duren out of the bullpen, but manager Bill Rigney, desperate for pitching of any kind, soon began to experiment with Duren as a starter. At times, Duren dominated the opposition, once striking out 12 batters in a game. But there were too many games where Duren struggled, his ERA eventually rising above 5.00.

Tragedy also struck the Duren family. During the All-Star break, Duren’s infant son, Craig, died at only two weeks old. Depressed over the loss of his son, Duren began to drink more. By season’s end, he was so physically exhausted that he was forced to check himself into a hospital. The Angels announced that he had been diagnosed with pneumonia, but in reality, Duren was in the throes of alcoholism, his body damaged by the effects of long-term drinking.

In 1962, returned to the Angels, but this time in the role of a relief pitcher. He pitched better for the Angels, but his ERA remained high (at 4.42) and his problems with control persisted. The following spring, the Angels traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies. Pitching for Gene Mauch, Duren made an adjustment by throwing more breaking pitches, as a way of setting up his fastball. The strategy worked; Duren lowered his ERA to 3.30 while splitting his time between the bullpen and the starting rotation.

After struggling in his first two appearances of 1964, Duren suddenly found himself on the move again. The Phillies sold him to the Cincinnati Reds, where he joined a team known for its wild group of personalities. It was not the kind of clubhouse atmosphere that Duren needed. He pitched well, but also became involved in a couple of alcohol-related incidents. Not pleased by the recurrence of his hard-drinking ways, the Reds released Duren in the spring of ’65. He then re-signed with Philadelphia before being released again. Duren signed with the Washington Senators, where he struggled, with his career coming to an end in August.

As tumultuous as Duren’s life had been, it only became more chaotic without baseball. Fed up with his drinking, Duren’s wife filed for divorce. Without a regular income from baseball and no savings to rely upon, Duren had to work a series of odd jobs. His financial situation became so dire that he ended up living in a flophouse before being committed to the Texas State Mental Hospital. Later released, Duren moved to Wisconsin, but his life remained so unhappy that he attempted suicide.

Finally, in the late 1960s, Duren reached a turning point. He checked himself into Milwaukee’s DePaul Hospital, where he underwent 22 months of treatment and rehabilitation. The time at DePaul saved Duren; he stopped drinking completely, overcoming his alcoholism and eventually becoming an addiction counselor. For the rest of his life, he offered advice and counsel to alcoholics, while working closely with numerous hospitals and agencies. He even returned to baseball’s good graces, becoming a regular on the old-timers’ circuit and a frequent participant in reunions. On occasion, he was asked to provide advice to ballplayers with ongoing drinking problems, something he did willingly.

Duren remained sober to the end. When he died in 2011 at the age of 81, he left behind a legacy of successful rehabilitation and assistance to countless others.

In looking back at Duren’s 1962 Topps card, we might be tempted to say that those tinted glasses and that intimidating countenance covered up the torment that he felt inside. By the end of his life, Duren still needed those glasses, but only to see. The torment had long since departed.

Ryne Duren entered the St. Louis Browns' farm system in 1949. But by the time he got to the big leagues in 1954, the Browns had moved to Baltimore and become the Orioles. He would make one outing before returning to the minor leagues for the next two summers. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

At the 1957 June 15th trading deadline, the Kansas City Athletics sent Ryne Duren, Harry “Suitcase” Simpson and Jim Pisoni to the New York Yankees for a package that included infielders Woodie Held, Billy Martin and right-hander Ralph Terry. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

In 1959, Ryne Duren lowered his ERA to 1.88 and struck out 96 batters in 76 innings.He pitched well through late September, but fell and broke a bone in his wrist, ending his season. Pictured above on Sept. 20, 1959, Duren watches on as the Yankees defeat the Red Sox 7-4 at Yankee Stadium. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

In 1963, Phillies manager Gene Mauch taught Ryne Duren to throw more breaking pitches, as a way of setting up his fastball. The strategy worked, as Duren lowered his ERA to 3.30 while splitting his time between the bullpen and the starting rotation. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Ryne Duren appeared in two 1960 World Series games, but was not called on by Yankees manager Casey Stengel in Game 7. Duren watched his team lose the title at the hands of Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski (pictured above) and the Pittsburgh Pirates. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman