- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1958 Topps Wally Post

#CardCorner: 1958 Topps Wally Post

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

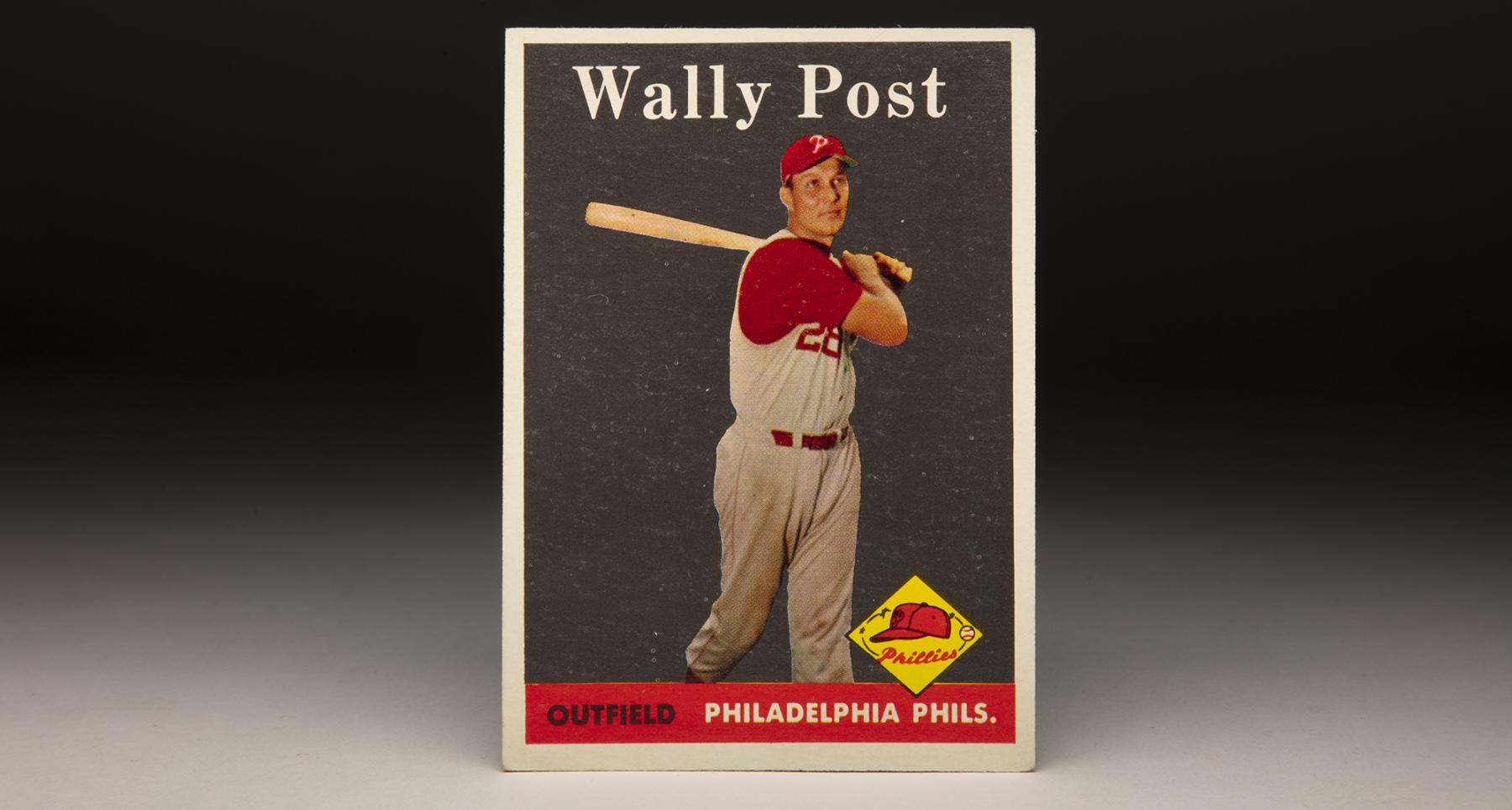

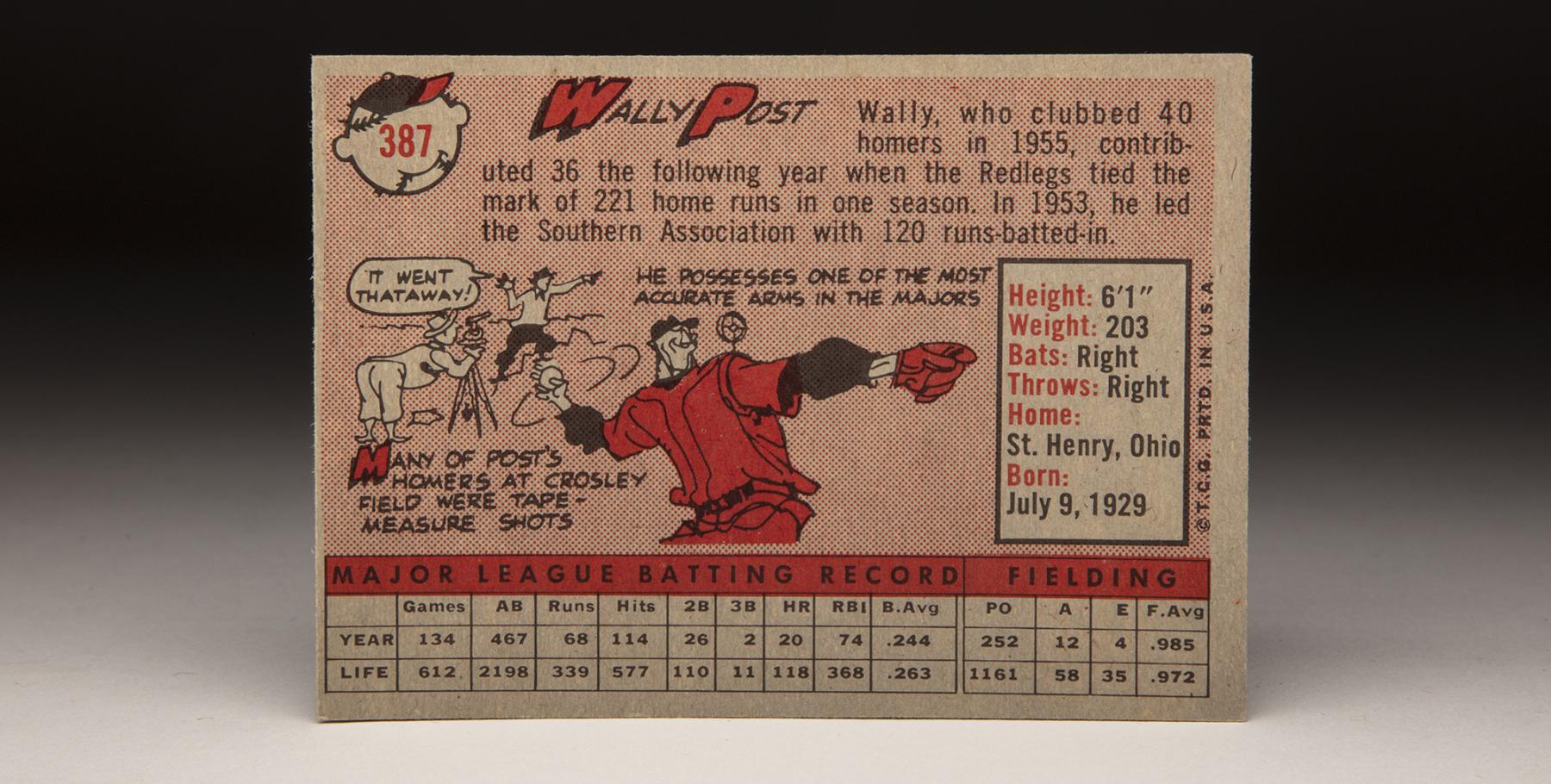

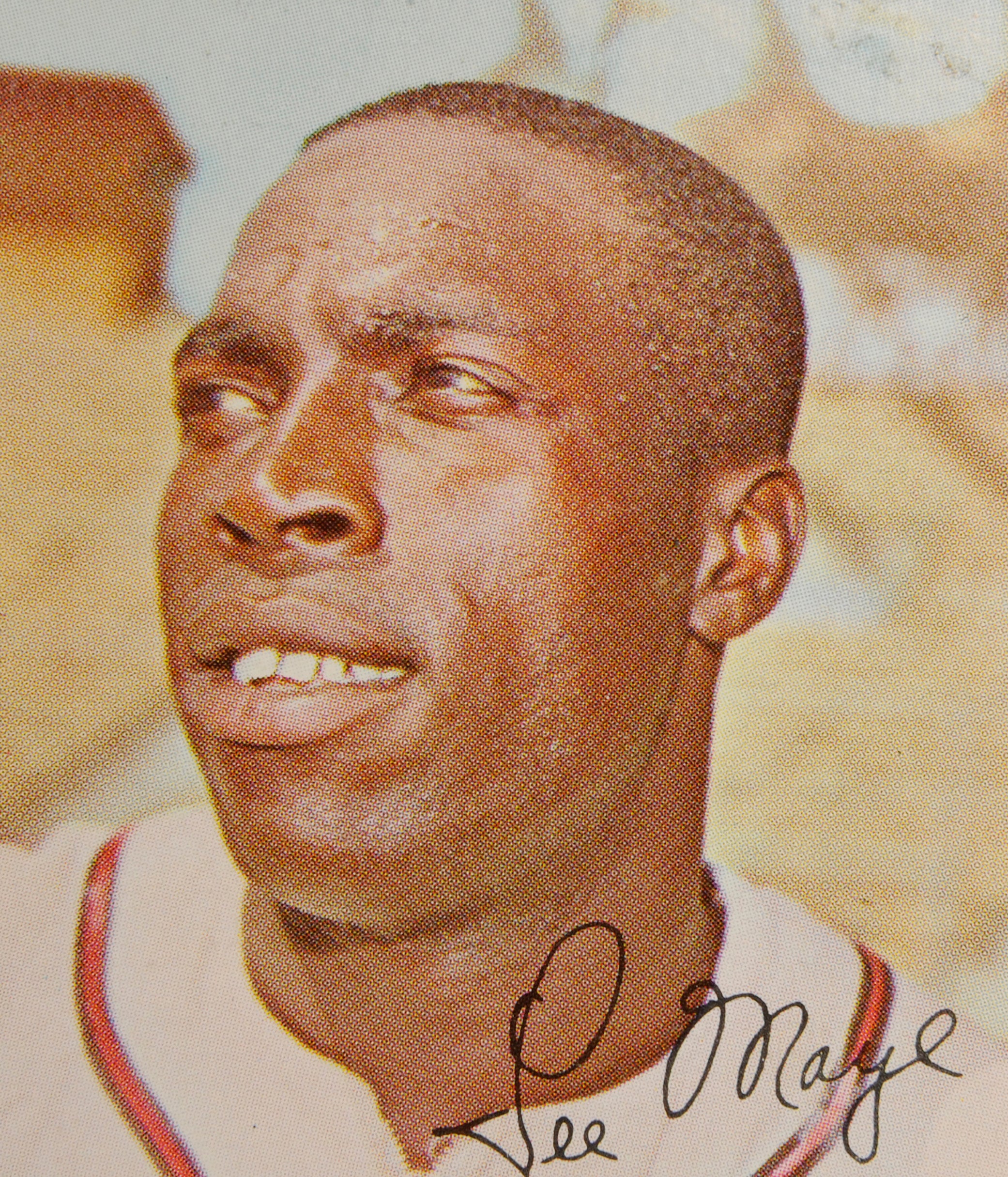

Something is a little off upon first review of Wally Post’s 1958 Topps card.

Yes, the maroon Philadelphia Phillies cap matches up with the team logo found in the bottom right-hand corner of the card. But the rest of the Phillies’ uniform doesn’t look quite right – and with good reason. The Phillies did not wear sleeveless uniforms during the late 1950s. Another team, the Cincinnati Reds, did wear such uniforms at the time.

In actuality, Post is wearing a Reds uniform on this card. That makes sense; he played the entire 1957 season with the Reds. Without an updated photograph for Post with his new team, Topps airbrushed a Phillies logo onto the cap and darkened the red of the Cincinnati sleeves to more closely match the Phillies’ maroon. And just like that, Topps created the illusion of a fully up-to-date card of a young slugger with his newest club.

All in all, this was pretty nifty artwork for Topps. The card also takes on a surreal look because of the black background. With most of its 1958 set, Topps applied a bright background color to each card – everything from blue to yellow to orange to green. For some reason, Topps chose the black backdrop for Post, giving us the impression that the photo had either been taken in the middle night or at the mouth of a very large and dark cave. Whatever the reason, Topps had produced one of its more intriguing and unusual entries for 1958.

In retrospect, it could be said that the manner in which Post made the major leagues was most unusual, too. Few players have taken his path.

Unlike most future major leaguers, Post did not play his first game until he was in high school, but he took to his new sport so well that he became an immediate star as both a pitcher and first baseman. It didn’t take long for him to draw interest from the major league team located closest to his hometown, the Reds, who viewed him first and foremost as a pitcher.

The Reds liked him so much that they signed him in 1946, during his junior year in high school. This would be illegal in today’s game, but the rules of the day permitted Post early entrance. Post, who was all of 16, reported to Middletown, a team in the Class D Ohio State League.

After a nondescript first year in the minor leagues, Post broke out in 1947 with the Muncie Reds, who replaced Middletown in the Ohio State League. He won 17 games, lost only seven, and posted an ERA of 3.33. Given such numbers, it seemed like Post had put himself on course as a pitching prospect.

He continued his pitching career with Columbia in the South Atlantic League, but also spent some time in the outfield. He pitched well, but batted only .178. Still, the Reds did not give up on him as an everyday player. In fact, they had him stop pitching in 1949 and fully concentrate on becoming an outfielder. As Post would later tell the Sporting News, the change made him happy. “I actually preferred the outfield from the start,” Post said. “But I could throw hard, so the Reds decided I should pitch [at the beginning of his career].”

Embracing his fulltime outfield role, Post started the season at Columbia, where he showed power and quickly moved up to a slightly better league, the Central League. He made six appearances for the Charleston franchise, and then without warning, he received the surprising news that he had been called up to Cincinnati.

In making his major league debut that September, Post bypassed Double-A and Triple-A ball completely. He played in six games for the Reds, picking up two hits in eight at-bats. He was all of 20, and while he did not look overmatched at the plate, he was not quite ready for fulltime duty in the big leagues.

The next summer, Post returned to the minor leagues, where he spent the entire year playing at Double-A Tulsa. Over the next three summers, Post experienced a series of fits and starts. He split each of the seasons between Cincinnati and various ports in both Double-A and Triple-A. For the most part, he put up big offensive numbers in the minor leagues, culminating with 33 home runs and a .927 OPS for Indianapolis of the American Association in 1953.

Post’s performance at Indianapolis convinced the Reds that he was ready for fulltime duty in the National League. In 1954, the Reds made him their regular right fielder. In 130 games, he batted .255 with 18 home runs, while slugging .435. While he showed promise, his lack of discipline at the plate also concerned the Reds. He drew only 26 walks against 70 strikeouts. In the outfield, Post’s play triggered no concerns. He played an impeccable right field, where he possessed a strong arm and managed to lead the league in outfield assists.

In 1955, Post made the necessary adjustments. He blossomed into stardom, hitting 40 home runs and batting .309. Post did not make the All-Star team that summer, but did receive some consideration in the MVP voting at the end of the season. He earned seven percent of the vote, good enough to place him 12th in the balloting.

Post also became known for hitting tape-measure home runs. As his manager, Birdie Tebbetts, explained in an interview, the husky slugger could hit fly balls farther than anybody in the game. “Post has a hand action that seems to give the ball an overspin,” Tebbetts told the Saturday Evening Post. “Once he gets it up in the air, it keeps on going. Whenever I see that ball start to rise, I always know it’s gone.”

On several occasions, Post hit home runs that cleared the dimensions of Crosley Field and struck a billboard located on top of a laundry across the street. The billboard read, “Hit Sign, Win Suit,” a special promotion run by the laundry that resulted in him acquiring several new suits that became part of his wardrobe. Some reporters described him as “the best dressed Red,” but Post never actually wore the suits, at least according to his son; the elder Post preferred to wear golf shirts without ties or jackets.

Post’s wardrobe reflected his reserved, modest personality. As a teammate, Post was quiet and soft spoken, but his pleasant nature made him well-liked in the clubhouse. Remarkably humble, Post never boasted about his playing skills or his status as a major leaguer.

Coming off his breakout season of 1955, Post did not play as well in ‘56, but he still belted 36 home runs and kept his OPS above .800. He drew some criticism for leading the league in strikeouts with 124, but his power numbers outstripped his tendency to strike out. Along with Frank Robinson, Ted Kluszewski, and Gus Bell, he helped formulate a powerful middle of the order in Cincinnati.

With his newfound fame, Post earned a spot on the TV show, What’s My Line?, in which he appeared as the “mystery guest” of the day. In 1957, Post turned 27, an age that often results in a player’s prime performance. For Post, his age 27 season resulted only in a falloff; he hit 20 home runs, 16 fewer than the previous season, while seeing his batting average fall to .244.

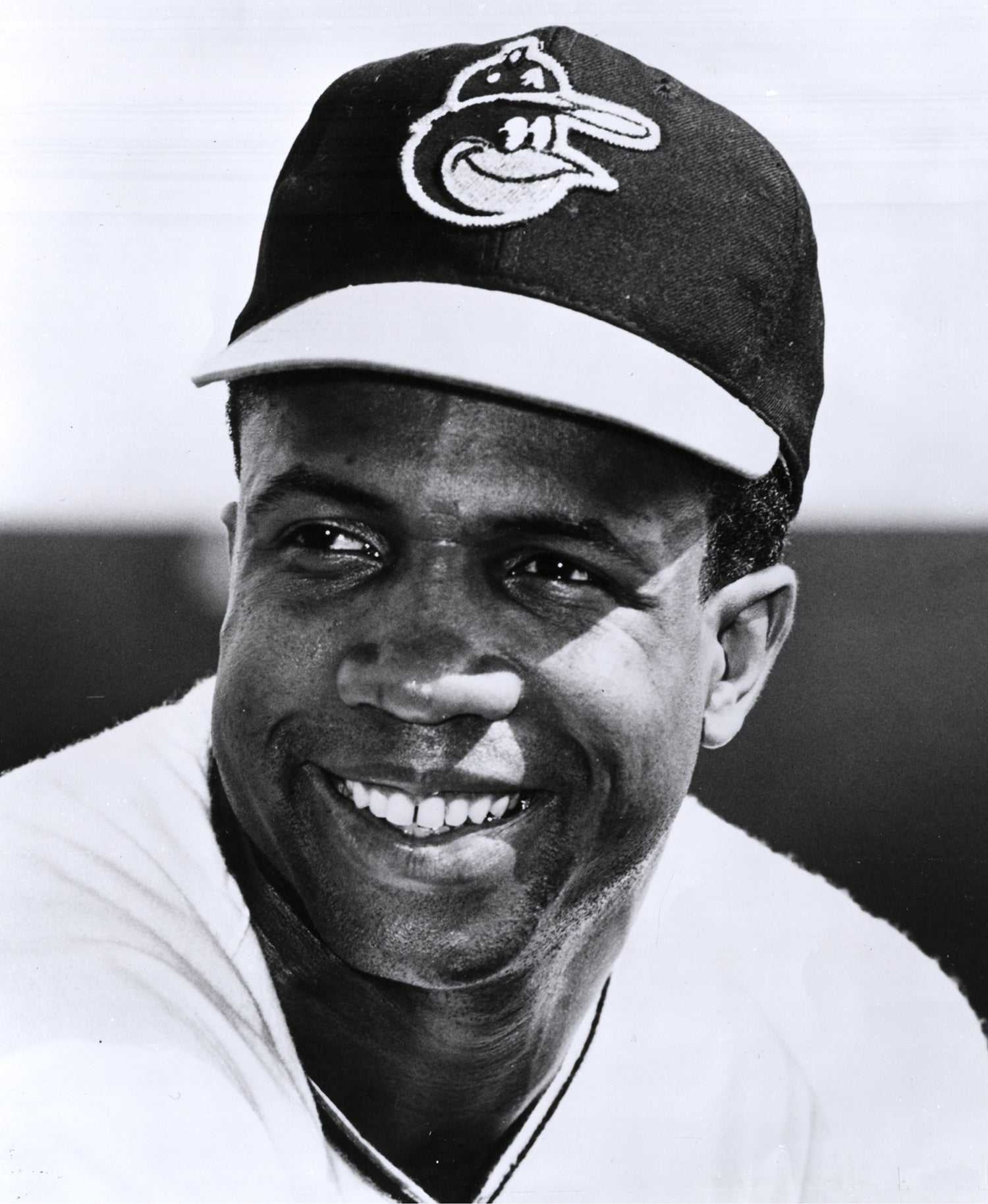

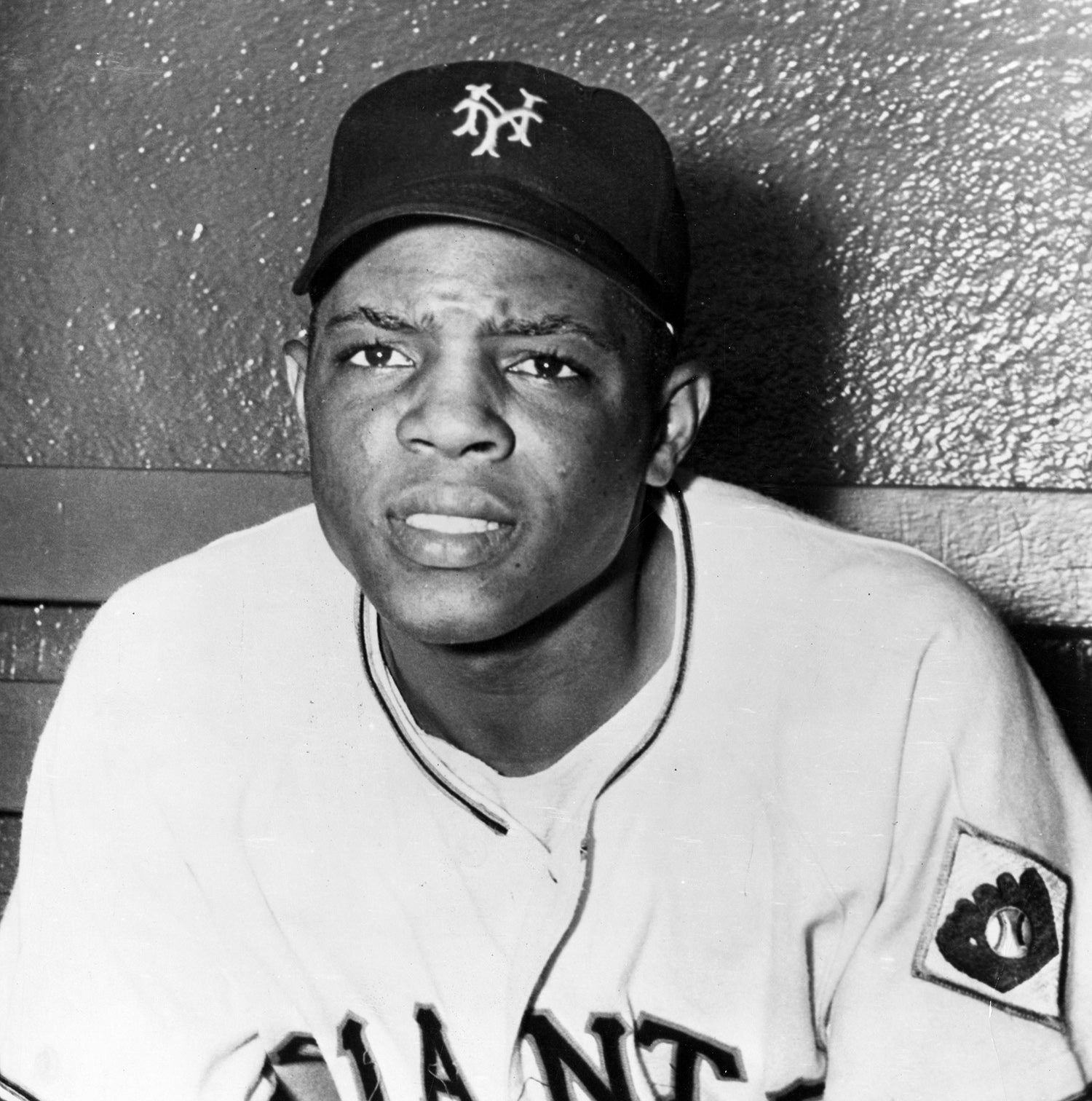

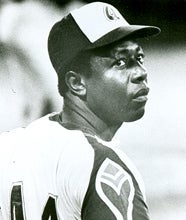

Post also became involved in an unwanted controversy, one in which he did nothing wrong. Despite Post’s drop-off in hitting, Reds fans stuffed the ballot boxes at Crosley Field, voting Post and seven other Reds onto the National League’s starting lineup for the All-Star Game. Believing that voting “irregularities” had taken place, Commissioner Ford Frick stepped in and removed three Reds from the All-Star lineup. The removals included Post and Bell, who gave up their starting spots in the outfield to a couple of players named Willie Mays and Hank Aaron.

As it turned out, Post would not have been able to play in the All-Star Game anyway because of an injury. Thanks to the bad timing, Post did not make it onto the All-Star Game roster at all. As it turned out, Post would never again earn selection to the Midsummer Classic.

In light of Post’s decline in 1956 and ‘57, the Reds made him available in trade talks over the winter. That December, the Reds struck a deal, sending Post to the Phillies for some needed pitching help, in the form of veteran left-hander Harvey Haddix.

The wintertime trade helped explain the reasons for the subterfuge behind Post’s 1958 Topps card. More importantly, Post’s first season in Philadelphia coincided with injury problems, which limited him to 110 games and only 12 home runs. But Post did improve his batting average, slugging percentage, and OPS with the Phillies, compared to his final season in Cincinnati.

In 1959, Post found better health and stayed in the lineup for 130 games, allowing him to hit 22 home runs and slug .457.

He returned to the Phillies in 1960, hitting well over the first quarter of the season. But when the June 15 trading deadline arrived, Post found himself leaving Philadelphia. The Phillies traded him, sending him back to the Reds, in exchange for a package of two younger outfielders, Tony Gonzalez and Lee Walls.

Post welcomed the trade from the Phillies, a non-contending team at the time. In rejoining the Reds, Post became the everyday left fielder and hit well over the balance of the season. In 77 games with Cincinnati, he batted .281 with 17 home runs and approached an OPS of .900.

The year of 1960 also brought Post some notoriety of a different kind. He appeared on the show, Home Run Derby, hosted by Mark Scott. In one of his appearances, Post squared off against Hank Aaron. Post won the one-on-one faceoff with Aaron, ending the Hall of Famer’s long run on the show.

Post remained productive in 1961, despite a series of injuries that limited him to 99 games. He made headlines during a game in St. Louis on April 14. Playing at the old Busch Stadium, Post hit a home run that caromed off the scoreboard located behind the left field bleachers. The ball struck am ornamental eagle located atop the scoreboard; Reds pitcher Jay Hook, a graduate of an engineering school, calculated that if the ball had not struck the eagle, it would have traveled 569 feet. Cardinals broadcaster Harry Caray described it as the longest home run he had ever seen.

For the season, Post hit 20 home runs and slugged .585, with those numbers becoming major factors in the Reds winning the National League pennant. Taking advantage of his first appearance in a World Series, Post played in all five games and batted .333 with a home run. Despite his hitting heroics, the Reds lost the Series to a powerhouse group of New York Yankees.

Post continued to hit well for the Reds in 1962, even though he appeared in only 109 games. Among the Reds, his .839 OPS ranked second only to Frank Robinson. That summer would turn out to be Post’s last hurrah. With the Reds boasting a talented and athletic outfield of Robinson, Vada Pinson and Tommy Harper, the aging Post became the odd man out in 1963. The Reds traded him early in the season; he finished out the year with the Minnesota Twins and then sipped a cup of coffee with the Cleveland Indians before being given his release.

He attempted a comeback with the minor league Syracuse Chiefs, but a lack of power and a sub-.200 batting average indicate that it was time to leave the game. At age 34, Post called it a career. Rather than remain in baseball in a coaching or front office capacity, Post went to work for a canning company owned by his father-in-law. It was not a glamorous job, but it was perfect for a modest, hard-working man like Post. He also maintained a slight connection to baseball by regularly attending winter baseball banquets in Cincinnati, where he usually spent time with former teammates like Gus Bell and Joe Nuxhall, among his closest friends on the Reds.

Sadly, Post was diagnosed with cancer in 1981, resulting in a series of hospital stays. The following January, he passed away at the home of one of his sons. Post was only 52. After his death, friends created the Wally Post Golf Open, a charity tournament that continues to be played in Mercer County, Ohio.

Perhaps Post’s early death explains why he has become a relatively forgotten Reds star from the 1950s and 60s, in the days that long preceded the franchise’s Big Red Machine. But he was an important part of some very good, power-packed lineups in Cincinnati. At a time when the Reds were respectable but not yet great, Wally Post was one of several bright spots – a good, humble teammate who was popular with the fervent fan base that filled Crosley Field.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

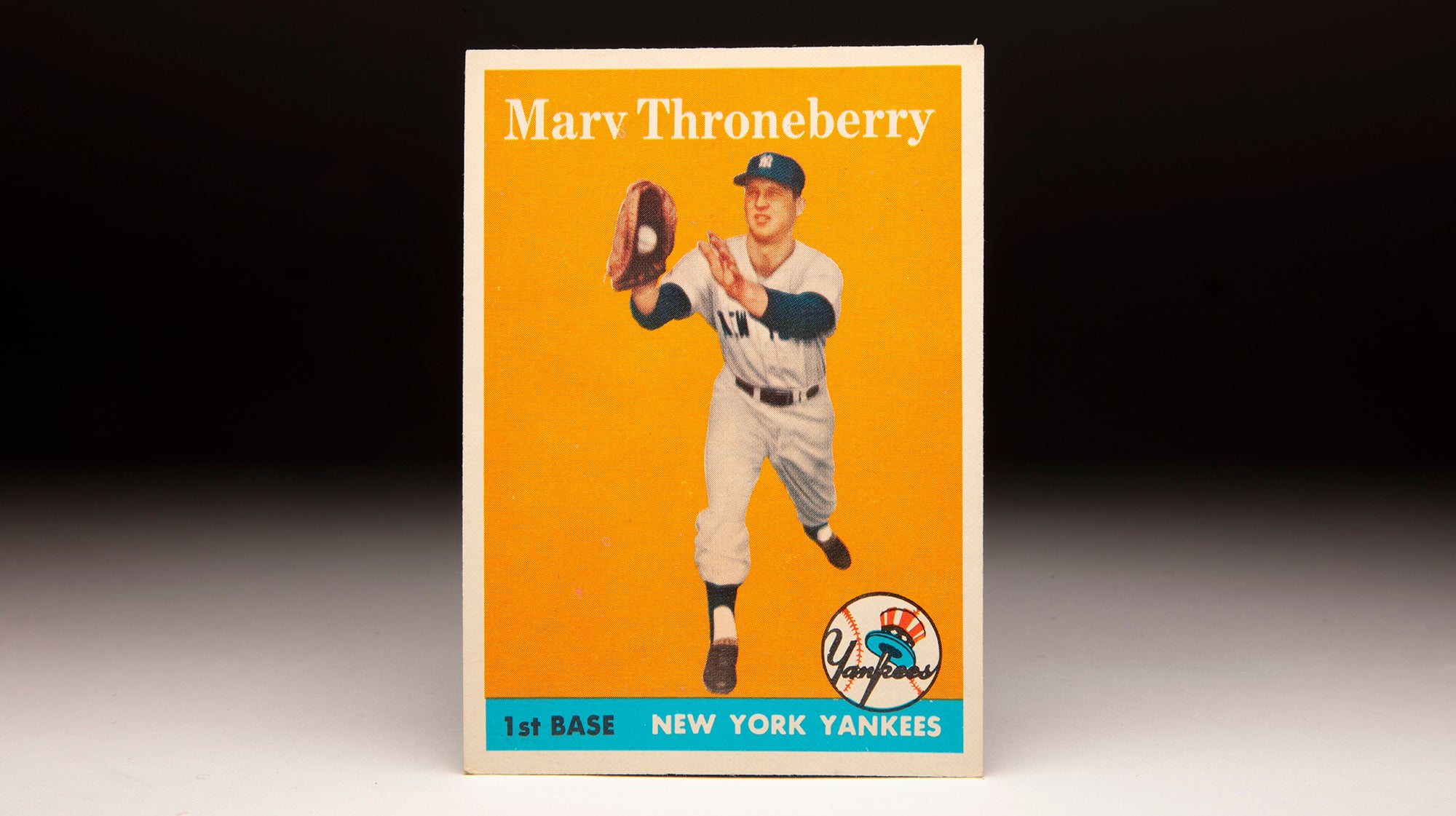

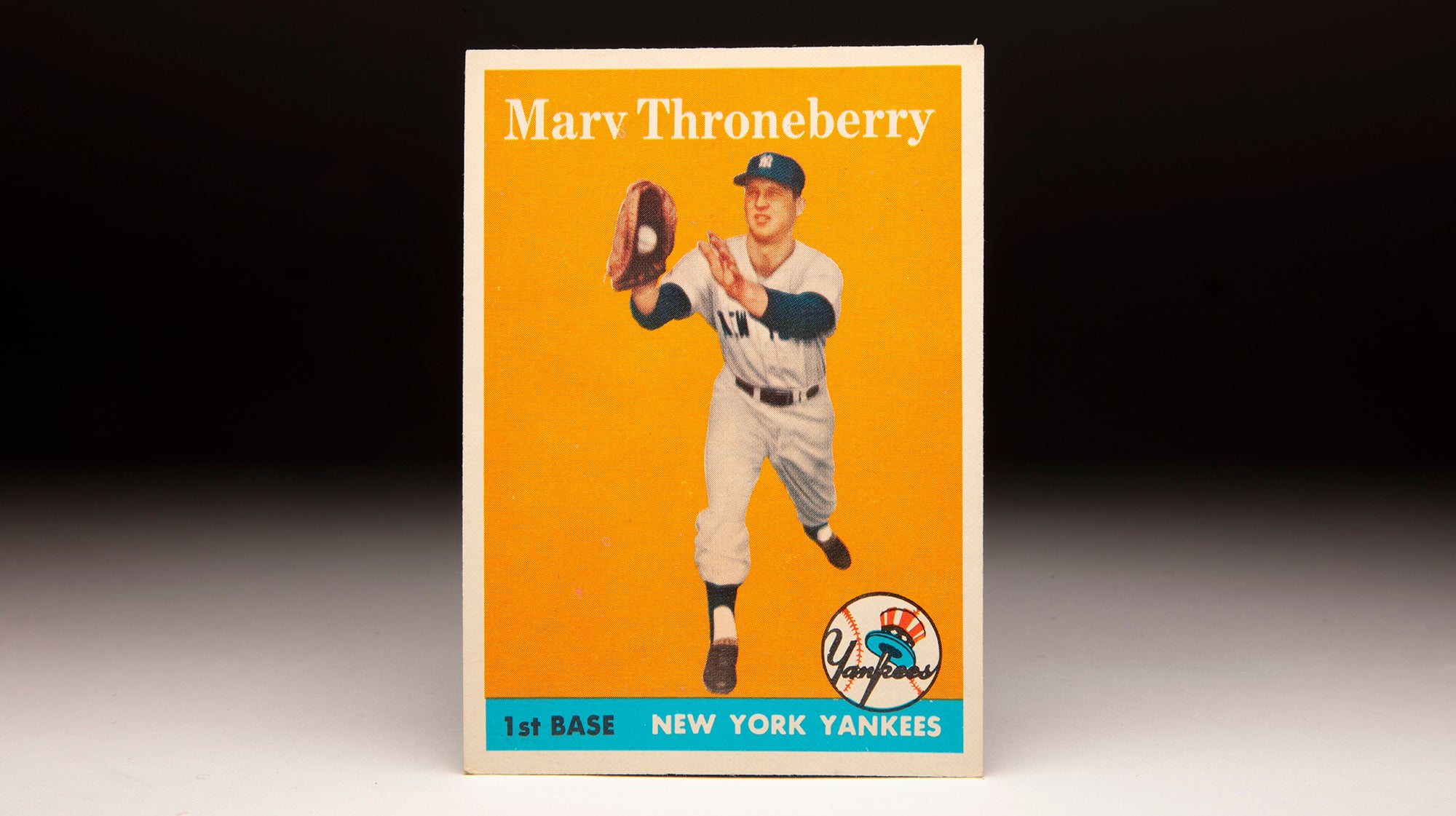

#CardCorner: 1958 Topps Marv Throneberry

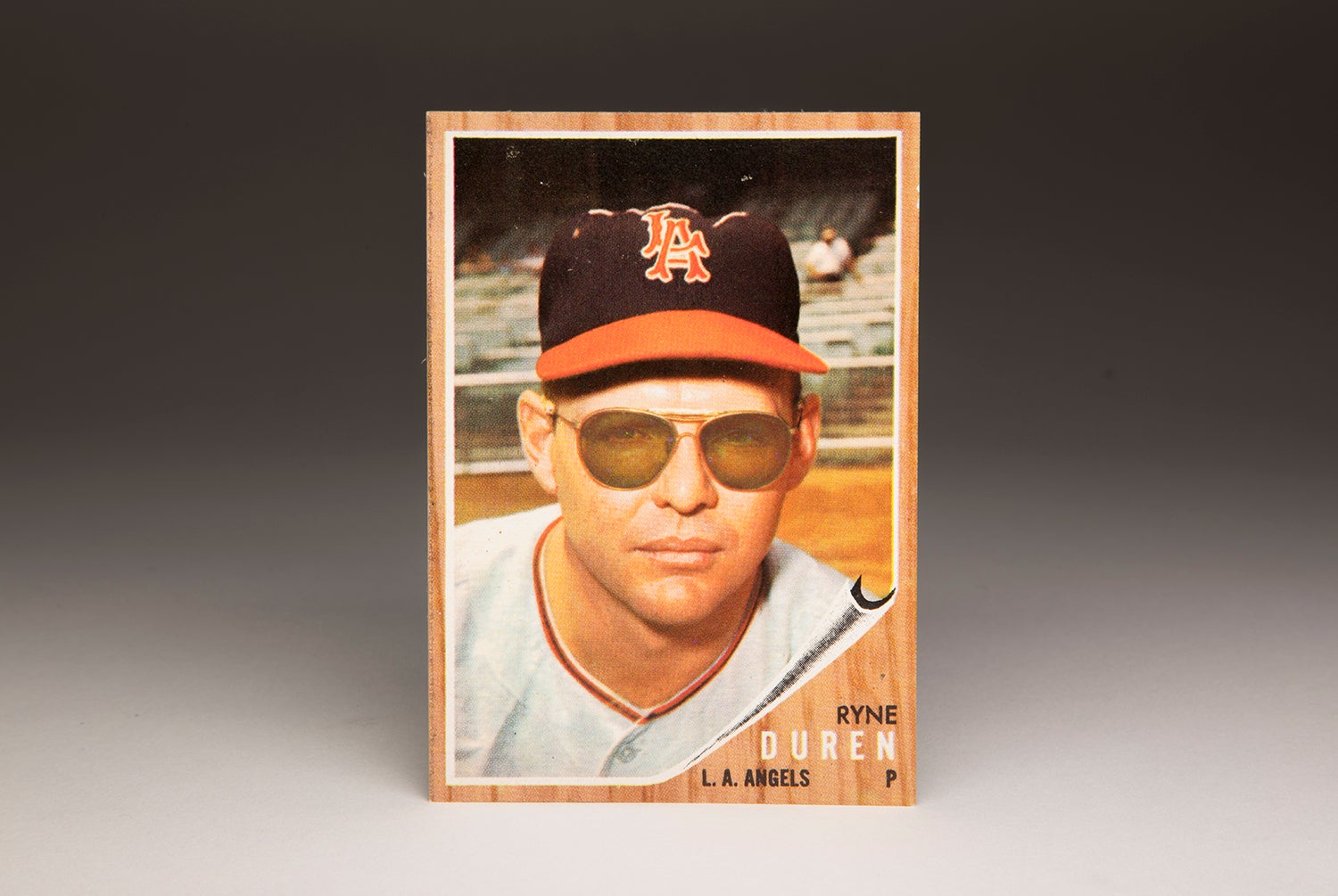

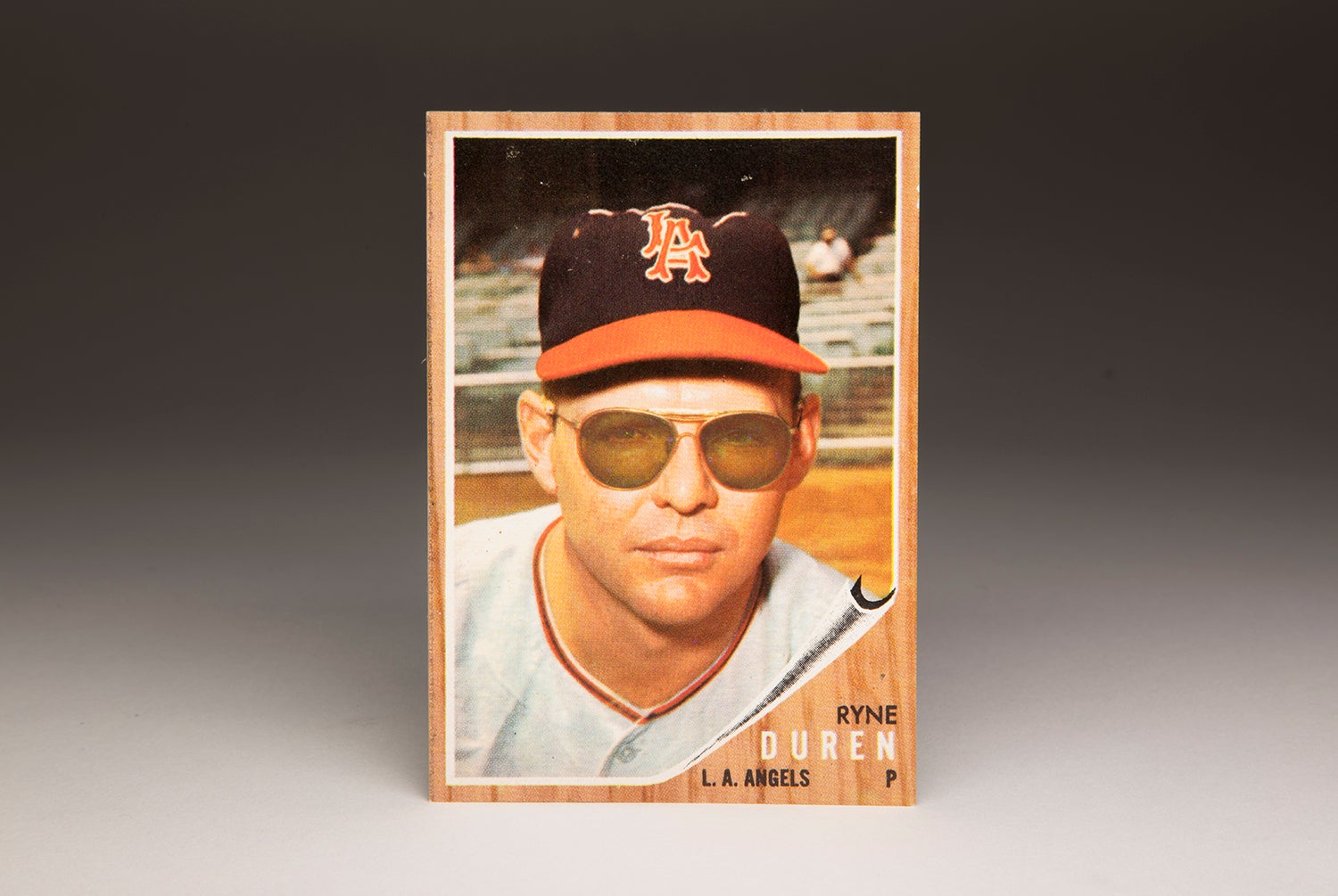

#CardCorner: 1962 Topps Ryne Duren

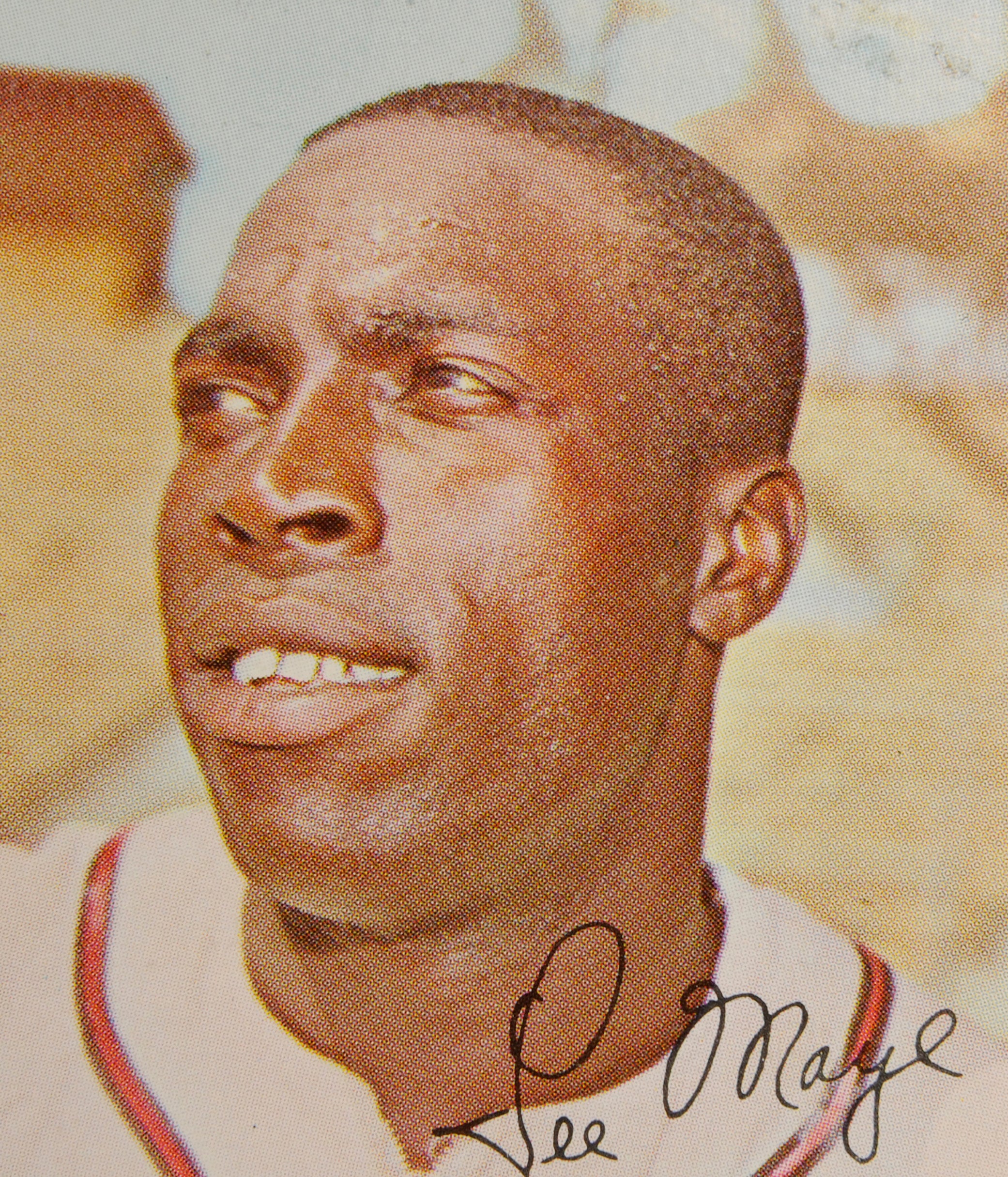

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

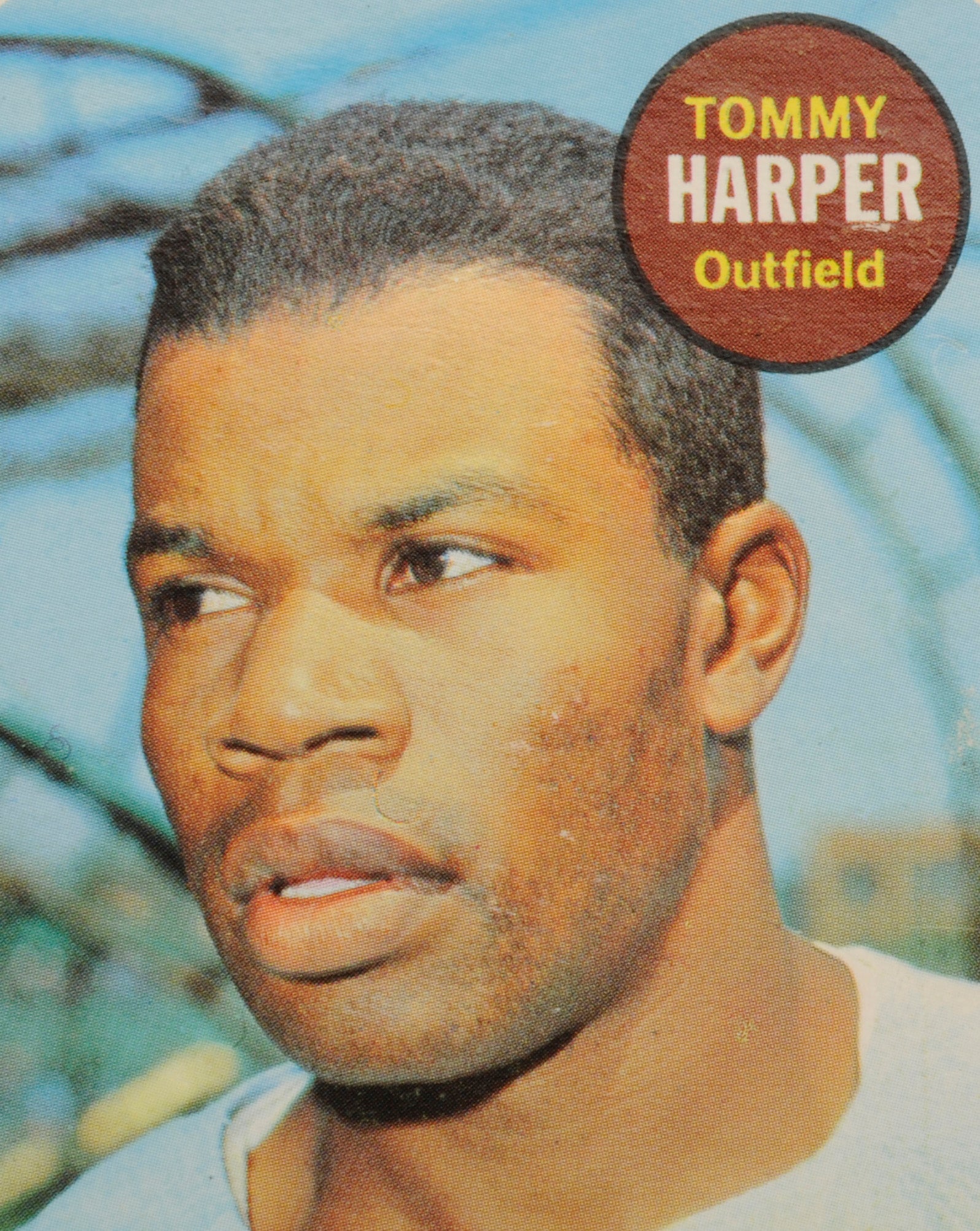

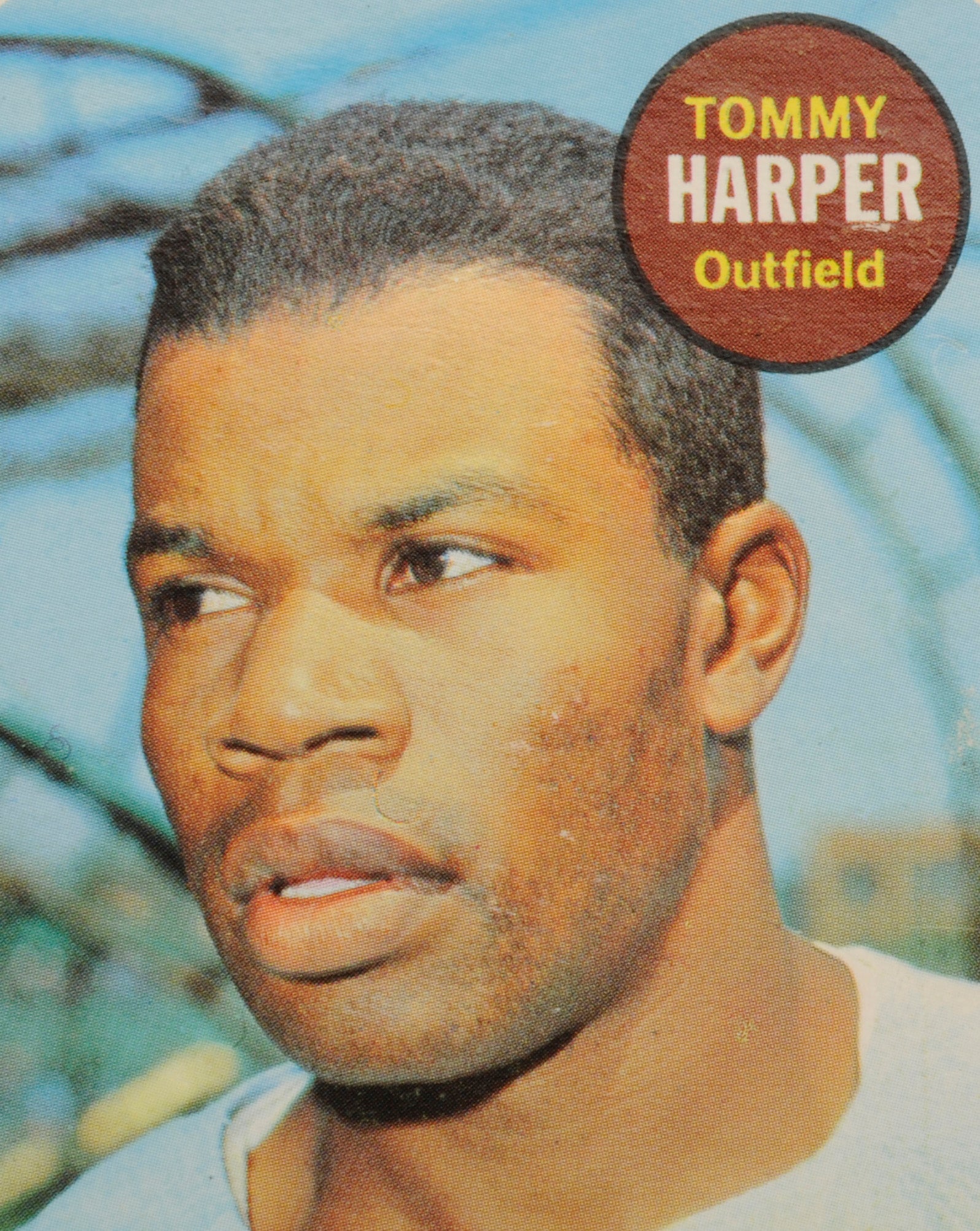

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Tommy Harper

#CardCorner: 1958 Topps Marv Throneberry

#CardCorner: 1962 Topps Ryne Duren

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye