- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Tommy Harper

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Tommy Harper

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

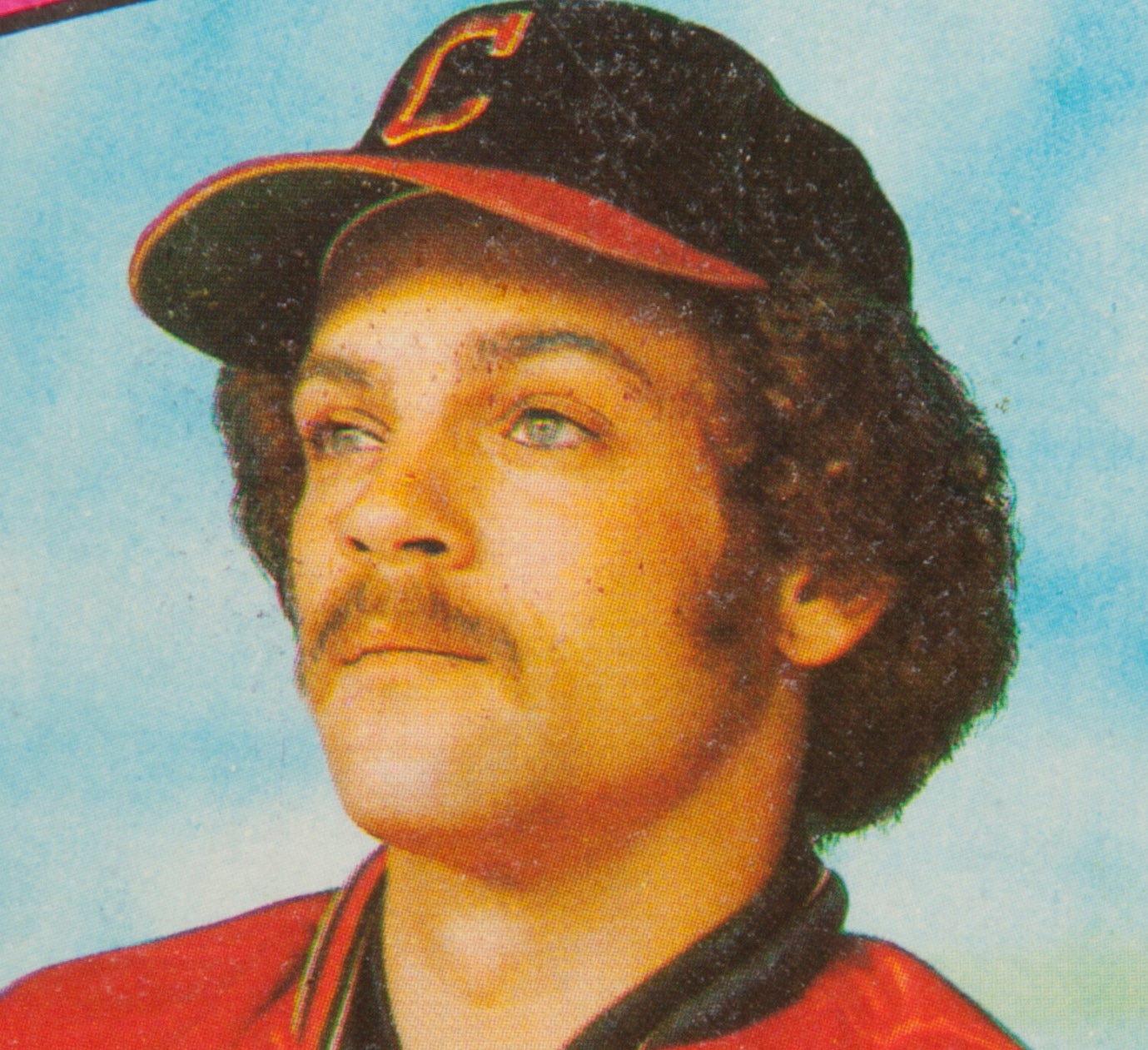

If you were collecting cards in 1969 and looking for a player wearing an actual Seattle Pilots uniform, you had to wait until the later series of Topps cards were issued that summer. Topps relied heavily on taking photographs from the previous season’s spring training, but in the case of the Pilots, there was no previous spring. As one of four new expansion teams, the Pilots did not start to congregate until February and March of 1969, making it impossible for Topps to feature Pilots uniforms on their early series of cards. That’s why the Pilots uniforms did not begin to show up until the fifth, sixth, and seventh series issued by Topps.

Late in the summer, we would see players like Jim Gosger, John Kennedy, and Bob Locker, all high-numbered cards, wearing Pilots uniforms. But for a player like Tommy Harper, who was card No. 42 and featured in Topps’ first series, he had to settle for the generic look. We see him wearing a plain, gray jersey, and without a cap. Given that look, he could have been playing for just about anyone in 1969.

Even without the Pilots’ blue and gold colors and without that wonderful cap they used to wear—including the so-called “scrambled eggs” featured on the bill—this is a pretty good photograph of Harper. We see him in close-up, with what appears to be a little bit of razor stubble on the left side of his face. We also see that he is wearing the short haircut that every player wore in the late 1960s. In 1969, it was still the military look, in contrast to the so-called hippies who were changing the hair and fashion choices in American popular culture.

For an expansion club like the Pilots, who basically relied on the players left over by the 20 established teams, Harper was available only because he had gone through a stretch of two atypically poor seasons in 1967 and ’68, when he hit .225 and .217, respectively. A fractured wrist, suffered during the first half of the 1967 season, didn’t help matters. Some scouts wondered if Harper had permanently lost his batting stroke. Some speculated that he was no more than a utility player.

When the Cleveland Indians left Harper unprotected in the expansion draft, the Pilots pounced. They believed in Harper’s talent; he had speed, and power, and the versatility to play both the infield and the outfield. And he was still young, only 27 years old and still in his physical prime.

It didn’t take long for Harper to become the best player on the team managed by Joe Schultz. Hegan and slugging first baseman Don Mincher would both earn selection to the American League All-Star team, but it was Harper who brought arguably the most value of any Pilot player. Splitting his season evenly between second base and third base—he played 59 games at each position—Harper drew 95 walks, led the league with 73 stolen bases, and scored 78 runs. His batting average, which was only .235, masked an on-base percentage of nearly .350. In addition to playing second and third base, Harper also filled in at all three outfield positions.

The sportswriters took notice of Harper and his understated value. Although the Pilots finished last in the American League West, Harper still received some back-of-the-ballot support in the league MVP voting. He finished 29th in the balloting, making him the only Pilot to receive votes of any kind for MVP. He also became popular with Pilots fans, who enjoyed his slash-and-dash style of play.

The Pilots lasted just the one season—they would become the Milwaukee Brewers just days before the start of the 1970 season—but the franchise became unforgettable through the pages of Jim Bouton’s Ball Four. Bouton wrote several passages about Harper, portraying him as having a good sense of humor. But Harper, like all other players of the day, had restrictions placed on what he could do. At one point, Harper told Bouton about conforming to baseball’s conservative standards. “[As] Tommy Harper once said: ‘In the winter, I have a beard, a mustache, and wear my hair long and natural. But before I come to spring training I have to shave off my beard and mustache and cut my hair. I feel like I’m going to boot camp.’ ”

Like many African-American players of the era, Harper had to deal with racism and negative stereotypes. When he first reported to spring training for the Cincinnati Reds in 1961, he arrived at the Tampa airport. He tried to place himself on line for a taxi, but a dispatcher told him, “Boy, this line is for white people only.”

Harper only became a better player after the franchise moved to Milwaukee, as the Brewers made him their regular third baseman and watched him sprout into stardom as a 30/30 player. Harper hit 31 home runs, stole 38 bases, and batted .296. He made the All-Star team and finished sixth in the MVP balloting.

Some scouts believed that Harper would become a perennial star, but “Tailwind Tommy,” as he came to be known in Milwaukee, couldn’t sustain that level of production. After an off year in 1971, the Brewers included him in a blockbuster trade for Boston’s George Scott. The Red Sox shifted Harper to a full-time outfield position, first in center field and then in right field. Over the next three seasons, he stole a total of 107 bases, giving the Red Sox their first dose of bigtime speed in years.

A downturn in 1974 resulted in a trade; the Red Sox sent Harper to the California Angels for utility infielder Bob Heise. No longer an everyday player, the aging Harper finished out his career as a versatile speedster for the Angels, Oakland A’s, and Baltimore Orioles, before calling it quits prior to the 1977 season.

Noted for his intelligence and even-keeled approach, Harper turned to coaching. He became a minor league instructor with the New York Yankees, before the Red Sox brought him back to town as a major league coach in 1980.

Harper later joined the Montreal Expos as a coach. There he became friends with a young right-handed pitcher named Pedro Martinez, who cited Harper for his influence and his advice.

Harper would later return to the Red Sox. He worked as a coach and now serves as a front office adviser for the Sox. He continues to be valued for his smarts and for his experience, which has included those bouts with Jim Crow segregation, that topsy turvy season with the Pilots, the breakout year with the Brewers, and his civil rights efforts.

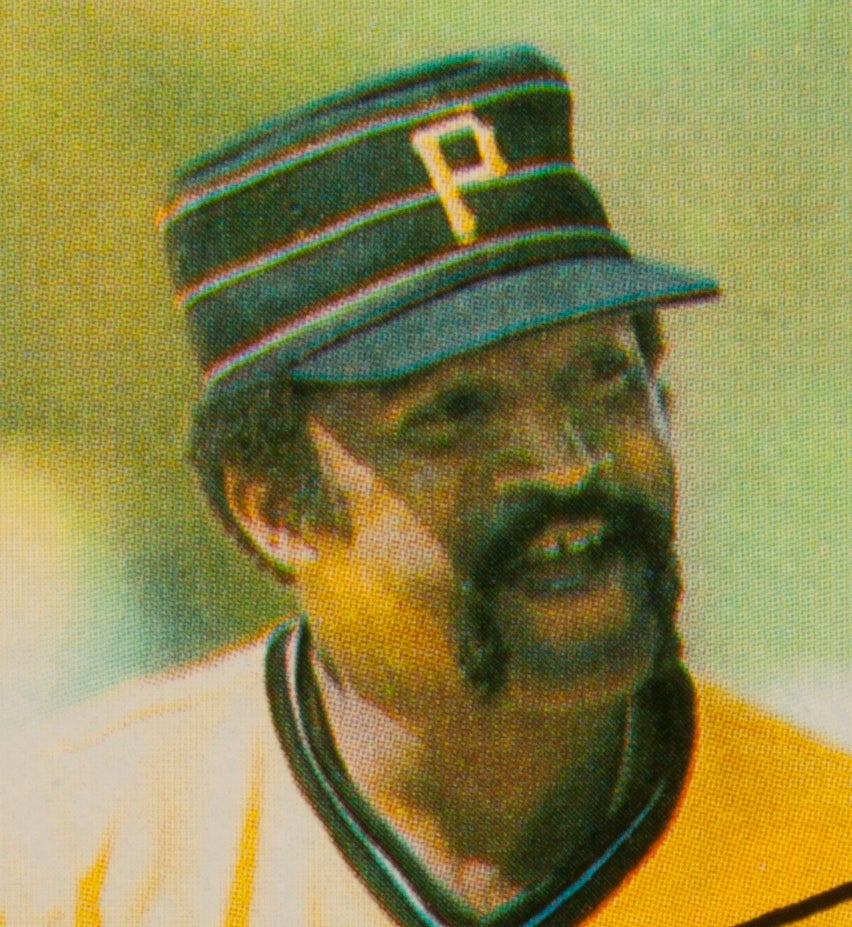

Harper is no stranger to Cooperstown, either. Back in 2004, he came to the Hall of Fame and participated in a public program in the Bullpen Theater, where he impressed visitors with his openness and his sense of humor. I asked him about his interest in baseball cards; he revealed that he had proudly collected all 14 of his Topps cards, including his 1969 card with the Pilots, and kept them as prized possessions in his home. He also talked about playing high school ball with Hall of Famer Willie Stargell and future Baltimore Orioles supersub Curt Motton in the Bay Area; what a team that must have been.

After his visit in ’04, we didn’t hear from Harper for a while. And then, this past summer, Pedro Martinez asked him to be one of his guests for Hall of Fame Weekend. After a layoff of 11 years, he came back to Cooperstown, where he heard his name mentioned by Martinez during a memorable induction speech.

Ever persevering, Harper keeps coming back. He has come back as a player, as a coach, and as a defender of civil rights. Tommy Harper just doesn’t give up.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde

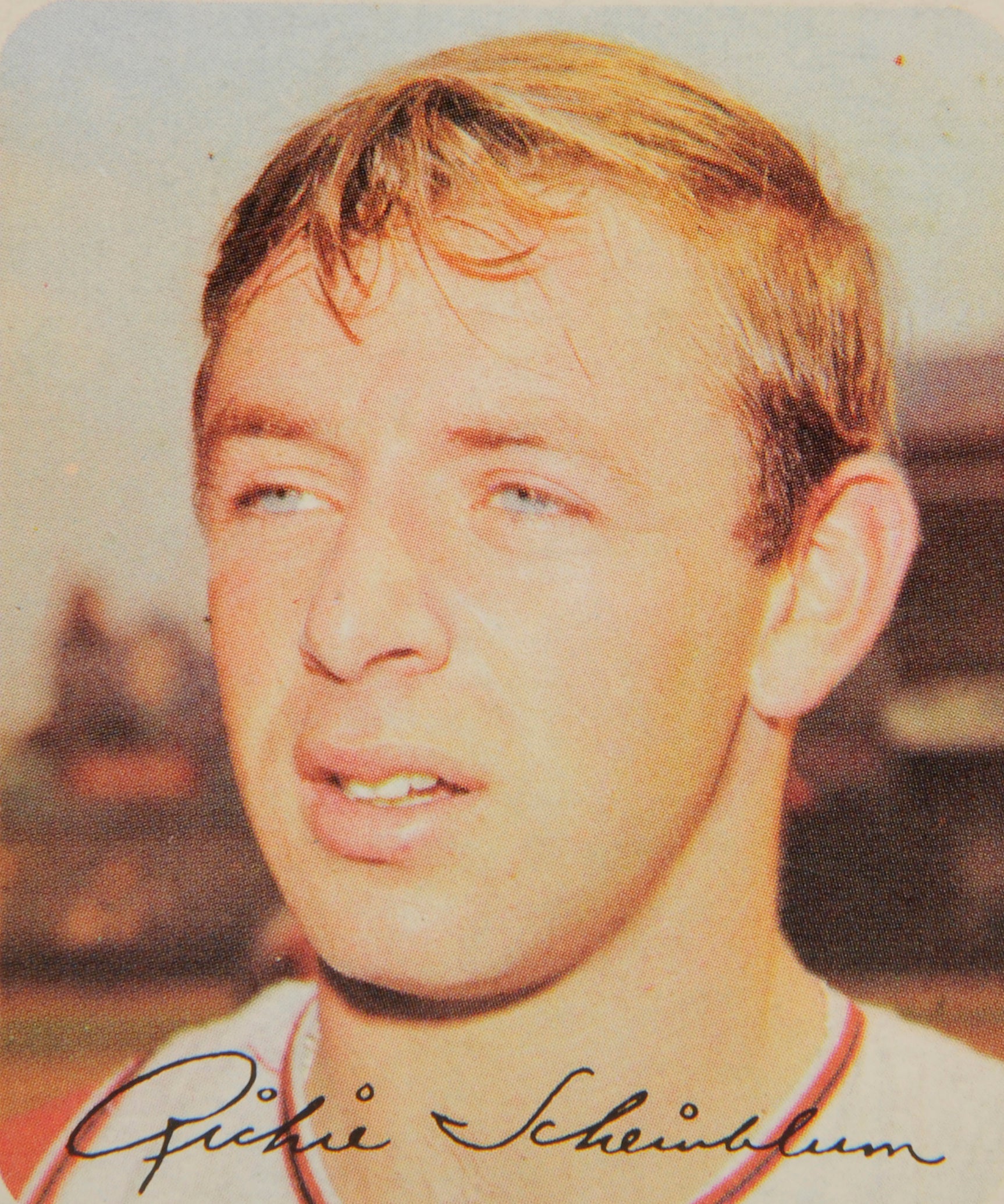

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

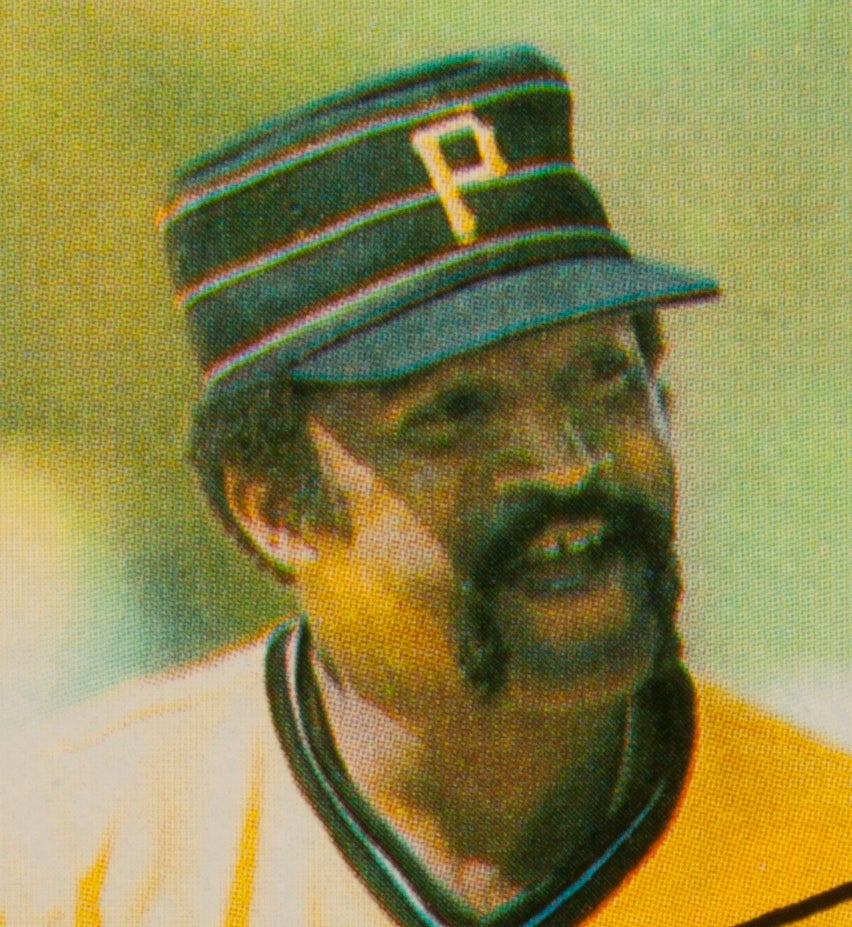

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

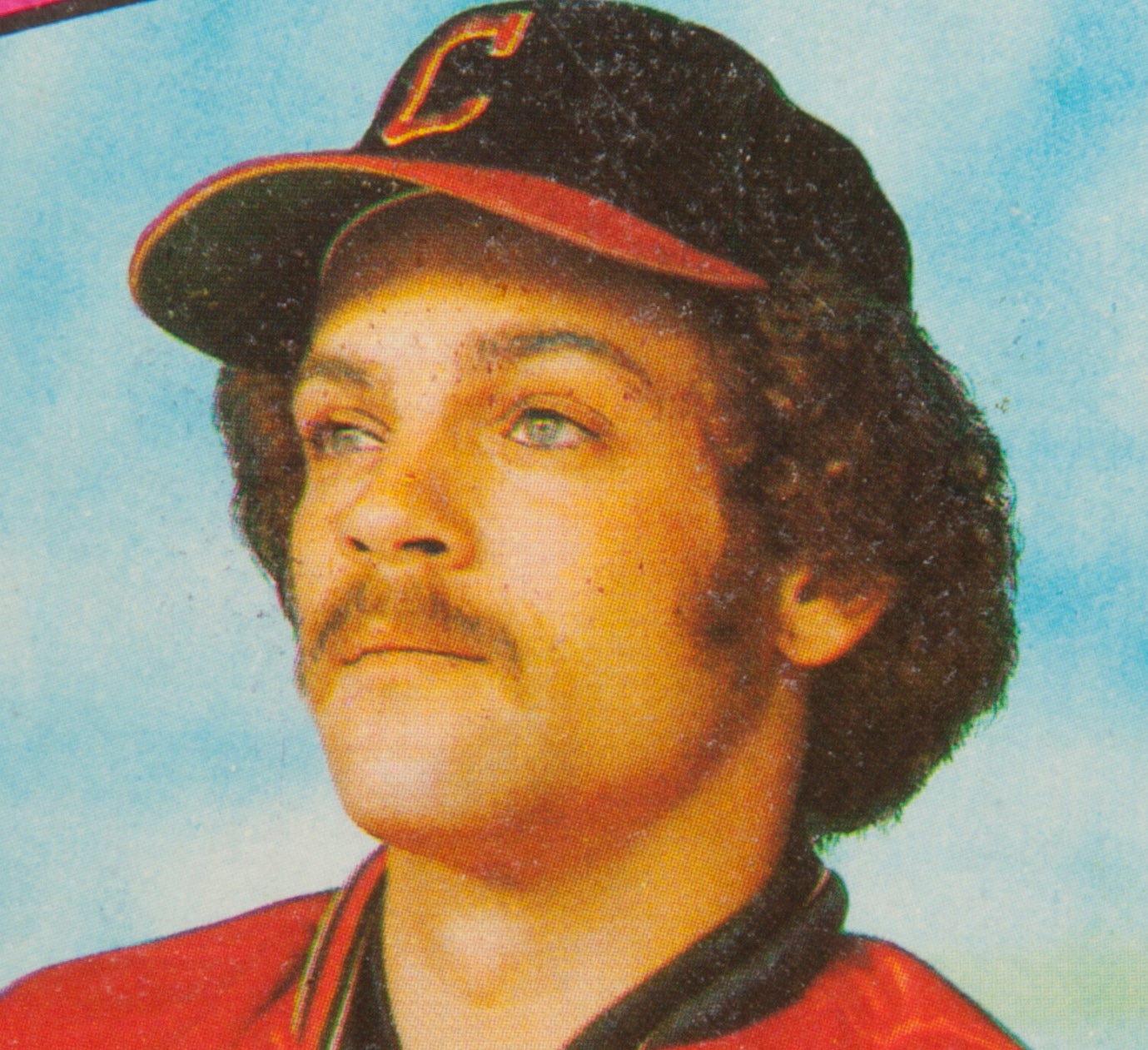

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde