- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Curt Blefary

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Curt Blefary

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

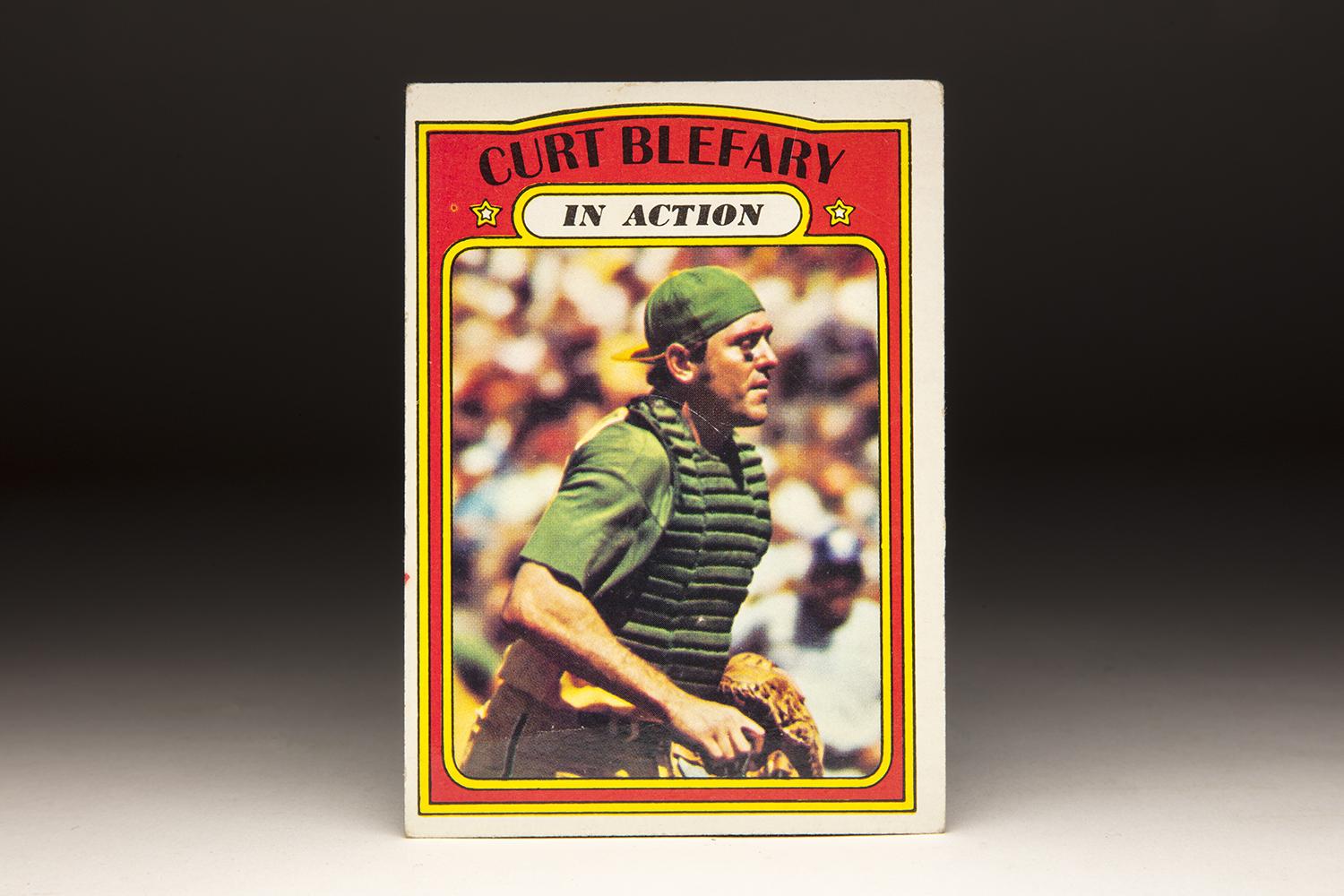

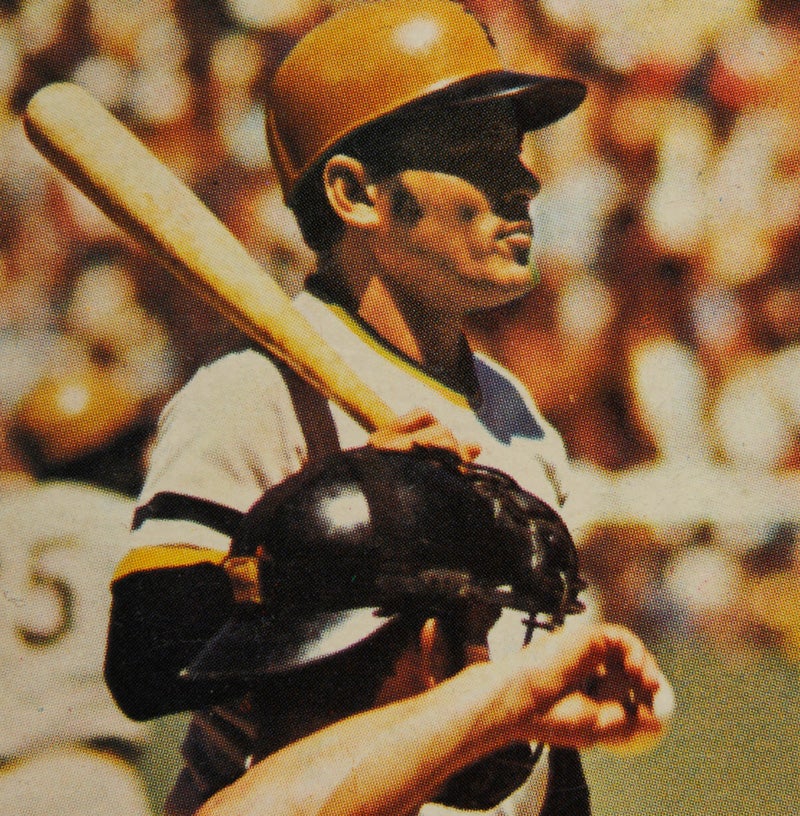

There is a strange irony to those baseball cards that showcase photographs of poor hitters holding bats in their hands. Similarly, it seems incongruous when a player with a reputation for below average fielding is shown wearing a glove or a mitt. That feeling comes to mind whenever I see Curt Blefary’s 1972 “In Action” card.

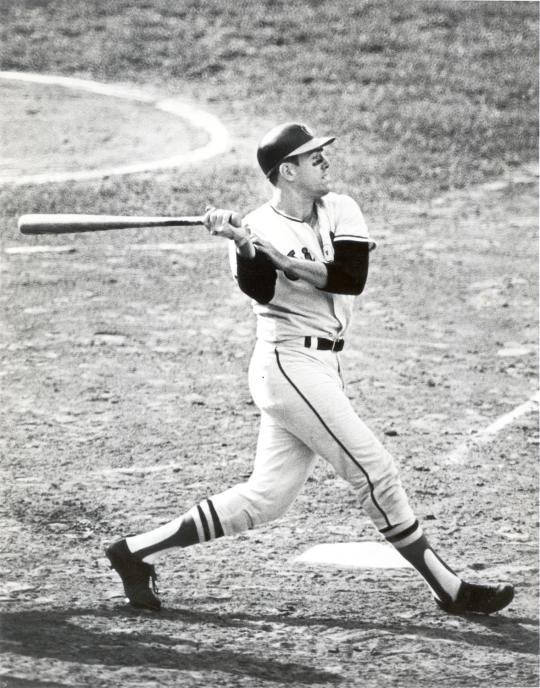

The card is one of the final two cards that Topps produced of Blefary, whose career came to an abrupt end in 1972. The photograph shows him wearing a mitt and the so-called catcher’s “armor,” most notably the bright green chest protector used by the Oakland A’s of that era. By the time this card came out, Blefary had long since earned a reputation as a clunky defender. After all, he was nicknamed “Clank,” which represented the imaginary sound that a ball would make as it clanged off of Blefary’s mitt. Blefary wasn’t just known for subpar catching, but also for his struggles at other positions, including first base, third base, and the outfield.

That is not to say that Blefary was a bad player, not at all. The man could hit; he had legitimate power from the left side of the plate and a knack for drawing walks. He also played hard. Blefary might not have been a skilled defender, but he brought enthusiasm and determination to the job. Blefary played wherever his managers asked him, and always put forth a strong effort, but he just didn’t have the skills to prevent him from being a defensive liability everywhere he played.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

I like the Blefary card not only because of the irony that it presents, but also because it epitomizes the tenacious and resolute role of the catcher. There’s just something cool about a catcher in his full gear on his baseball card. With his mitt on his left hand, the ball in his right hand, his cap turned backwards, and old-style lampblack visible under his right eye, Blefary looks very much the part of a gritty receiver who is ready for action and prepared to get a little dirty over the next nine innings.

It was largely because of Blefary’s action card that I became interested in learning more about him. Research into Blefary’s career and life have proved fascinating, presenting us the story of an outspoken player who struggled with alcoholism, but eventually found a way to overcome his personal demons. And then, he was gone – taken from us at too young an age.

Blefary’s career began in 1962, when the New York Yankees signed the Brooklyn-born youngster as an amateur free agent. Blefary spent a season and a half in the Yankees’ minor league system, but a technical error on the part of the Yankees’ front office exposed him to waivers, allowing the Baltimore Orioles to put in a claim. Thrilled to have a top prospect for the meager cost of the waiver fee, the Orioles assigned Blefary to Elmira of the Eastern League and converted him from outfield to first base. They also counseled Blefary about his temper, which had become a concern during his days in the Yankee farm system. Blefary didn’t hit much for Double-A Elmira, but the Orioles still promoted him to Triple-A Rochester in 1964.

Splitting his time between first base and the outfield, Blefary exploded as a hitter with the Red Wings. He belted 31 home runs, drew 102 walks and assembled an OPS of .924. Hoping to make the Orioles’ roster, Blefary reported to Spring Training in 1965, but began to complain that manager Hank Bauer wasn’t giving him enough playing time in exhibition games. “Sometimes my mouth would get into gear before my brain was engaged,” Blefary explained to the Baltimore Sun. “I did not get to the big leagues being shy. I got the attitude from my father.”

In spite of his verbal complaints, Blefary made the Orioles’ Opening Day roster and emerged as the regular right fielder against right-handed pitching. Blefary hit 22 home runs and coaxed 88 walks to earn American League Rookie of the Year honors. He also impressed Bauer with his hustle and work ethic. His colorful personality, which showed itself through his patented “Cadillac Trot” on home runs, made him popular with Baltimore fans.

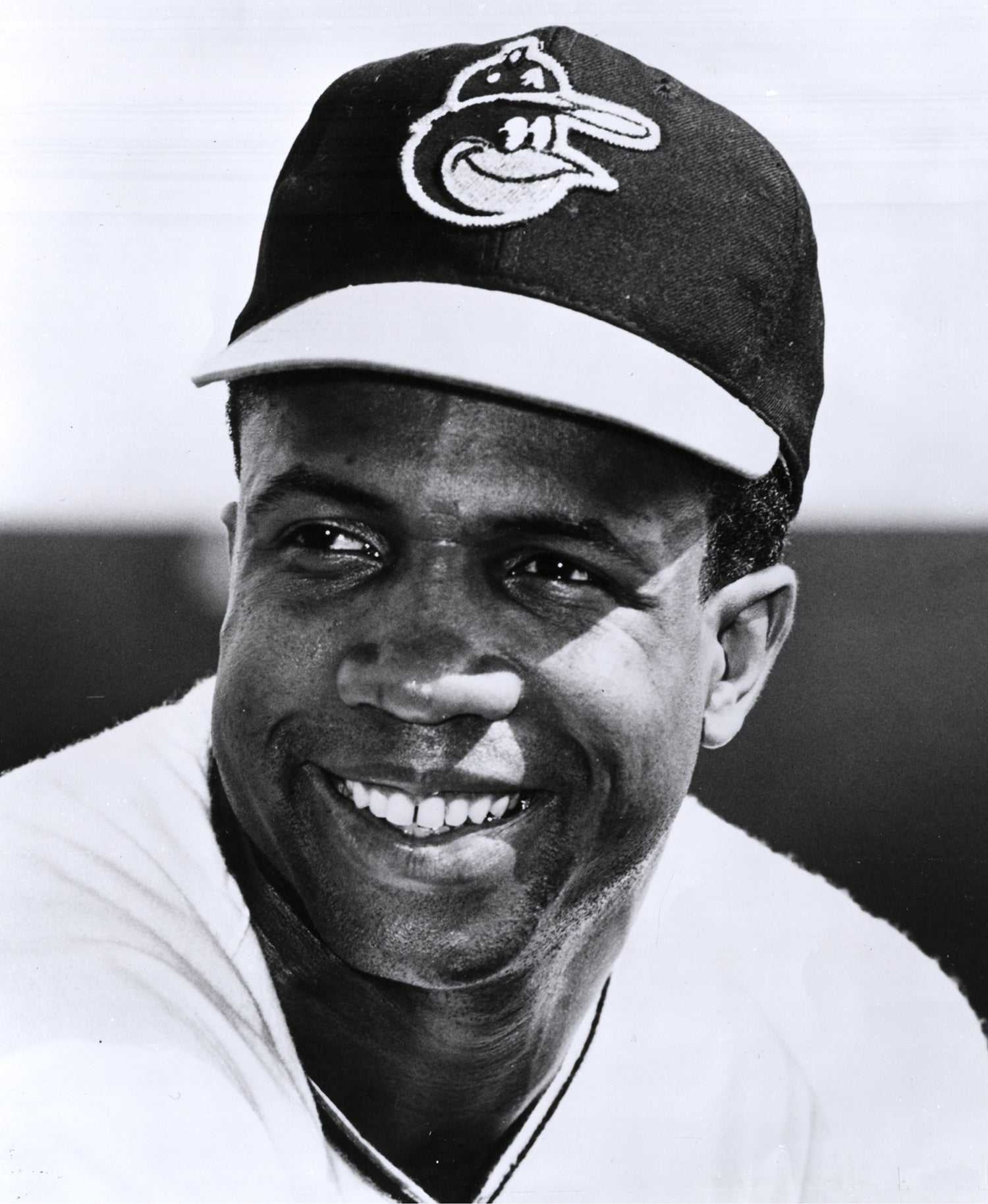

Over the next two seasons, including Baltimore’s world championship season of 1966, Blefary remained a force in the Orioles’ lineup. His batting average dipped, but he continued to hit home runs and draw walks, while playing the corner outfield positions and first base. Blefary’s defensive shortcomings also started to become the stuff of legend. One day, Orioles star Frank Robinson dubbed Blefary as “Clank”. According to an oft-repeated story, the team bus drove by a pile of scrap iron one day, prompting Robinson to yell toward Blefary, “Go get yourself another glove.” The Orioles’ players erupted in laughter.

Thanks to his power production, Blefary looked to be solidly entrenched in Baltimore, but then came the stumbling block of 1968. It was the Year of the Pitcher, with conditions including an expanded strike zone and increasing ballpark dimensions conspiring to make life difficult for many hitters. The Orioles also experimented with Blefary as a catcher, while still using him as a first baseman and outfielder. The constant switching of positions seemed to affect Blefary, who saw his batting average fall all the way to .200. His power also dropped, as he hit only 15 home runs in 137 games.

Blefary’s struggles, combined with a tendency to lose his temper and some sparring with new manager Earl Weaver, convinced the organization to shop the young slugger that winter. One rumor had Blefary headed to the Chicago Cubs, but ultimately the Orioles settled on a different trading partner. They sent Blefary to the Houston Astros for left-handed pitcher Mike Cuellar and infielder Enzo Hernandez. Rather than use him in the outfield, the Astros made Blefary their starting first baseman. On the surface, his Astro numbers – a .253 batting average and 12 home runs – looked modest, but a deeper examination revealed something else. Blefary drew 77 walks and reached base at a clip of nearly 50 percent. His offensive numbers also looked better in the context of the extreme pitching conditions of the Houston Astrodome, a stadium what was not exactly tailored to a power hitter like Blefary.

Off the field, Blefary made news because of his friendship with African-American pitcher Don Wilson (also profiled in a recent edition of Card Corner). In 1969, Blefary and Wilson became roommates on the road. In so doing, they made history as the first interracial roommates in the history of the National League. The arrangement drew praise from the media, but it angered some racist fans. Blefary received hate mail berating him for daring to room with a player of color.

Blefary also drew praise from some of his teammates in Houston. In his iconic book, Ball Four, Jim Bouton lauded Blefary as an ideal teammate, the kind of guy you wanted to have in “a foxhole.” Bouton also credited Blefary for the off-season work that he did with children of special needs.

All things considered, Blefary did decently for Houston, but he clashed with manager Harry Walker, who tried to force the slugger to cut down his swing and use the entire field. Bristling at such a suggestion, Blefary preferred a pull-hitting approach and eventually asked for a trade. After the season, the Astros accommodated him, sending him back to his original organization: the Yankees. In exchange, the Astros acquired the ever-colorful Joe Pepitone.

After the trade, Blefary received sharp criticism from the Houston media. Longtime sportswriter John Wilson offered this assessment in the Sporting News. “Blefary has failed to see eye-to-eye with his last two managers, Harry Walker at Houston and Earl Weaver at Baltimore. He showed a lack of restraint in expressing displeasure with the way he was being handled and asked to be traded from both teams.”

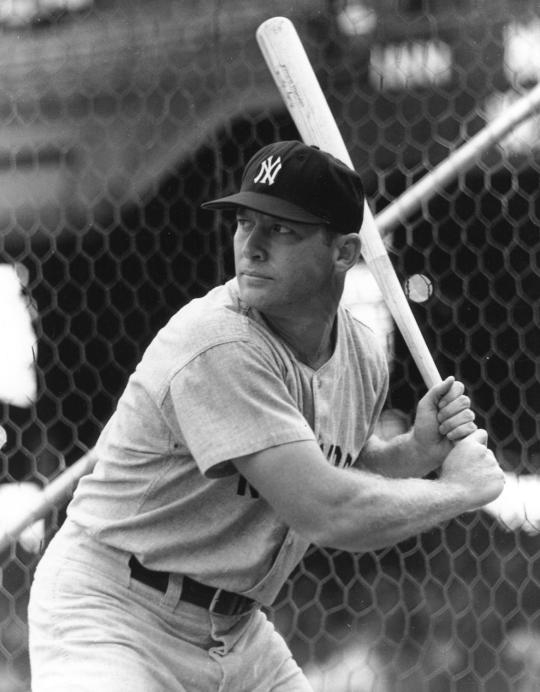

For his part, Blefary was thrilled with the trade to the Bronx. “I’m a local guy and I wanted to play in New York,” Blefary told the Newark Star-Ledger. “Mickey [Mantle] was my idol, and I always wanted to play with him.” Mantle was already retired, but the Yankees still offered him a chance to take aim at the short porch in right field. They certainly had no intention of tinkering with Blefary’s swing; they wanted him to pull the ball. With his left-handed power stroke, the team viewed Blefary as a natural for the Stadium, where he had always hit well as a visiting player.

The situation seemed perfect for all concerned, but Blefary started his first season in the Bronx with a thud. He didn’t hit his first home run of the season until June 2. Unable to get untracked, Blefary put up bad numbers: A .212 batting average and only nine home runs. Unfortunately, the short porch at Yankee Stadium lulled Blefary into the bad habit of trying to pull everything. Blefary became obsessed with trying to hit home runs into the right field stands. In so doing, he fell into one of the worst batting slumps of his career.

Blefary also bristled at manager Ralph Houk’s decision to platoon him, rather than use him against both left-handed and right-handed pitching. Blefary felt that he needed to play every day in order to hit and came to resent Houk, a manager who was generally liked by his players.

Determined to make a comeback, Blefary lost 20 pounds during the winter, but it didn’t help. Early in 1971, he lost his right field job to Ron Blomberg, another young left-handed hitter with power. Reduced to a pinch-hitting role, Blefary lasted until late May, when the Yankees traded him to the A’s for pitchers Rob Gardner and Darrell Osteen. Just like that, Blefary’s Yankee days had ended.

A’s manager Dick Williams made Blefary a utility player, using him at catcher, around the infield and in the outfield. In 1972, Blefary began Spring Training as the No. 2 catcher behind starter Dave Duncan. Blefary hit a robust .360 in Grapefruit League play, but somehow fell to fourth-string status behind Duncan, Gene Tenace and Larry Haney. As the No. 4 catcher, Blefary didn’t figure to play much for the A’s.

Prior to the season, Blefary expressed his dissatisfaction. He gave the A’s a play-me-or-trade-me edict. One day later, Blefary apologized to Williams for putting his skipper on the spot right before Opening Day.

To his credit, Blefary kept himself ready to play. In his first 11 at-bats of the season, he collected five hits. But ultimately, his status on the depth chart, coupled with his trade demand, motivated owner/general manager Charlie Finley to make a move. In May, Finley traded Blefary to the San Diego Padres as part of a package for veteran outfielder Downtown Ollie Brown (also the subject of a previous Card Corner).

Somewhat surprisingly, Blefary did not embrace the trade with open arms. At first, Blefary told the Padres that he wanted to renegotiate his contract. Otherwise, Blefary planned to retire and become a policeman.

A couple of days later, Blefary changed his mind and reported to San Diego. Blefary played sparingly with the Padres and didn’t hit much as a backup catcher and outfielder. In January of 1973, the Padres released Blefary.

Still believing that he could contribute, Blefary received an offer of a Spring Training invite from the Atlanta Braves. Blefary reported to camp, but couldn’t crack the team’s Opening Day roster. The Braves sent him to Triple-A Richmond, where he appeared in seven games before deciding to retire. At the age of 29, Blefary was done.

The timing for Blefary could not have been worse. The American League had just adopted the designated hitter role – a rule that was made for a player like Blefary. But no AL team showed interest in signing him, forcing Blefary to step aside.

Blefary was ill prepared for life after his playing days. He took on a variety of jobs, from serving as a bartender to working as a fast food cook to putting in time with a sheriff’s office, but he longed for a job in baseball. He contacted several teams about working as a coach or instructor, but no one would hire him. Most teams did not even respond to his inquiries.

In a 1995 interview, Blefary admitted that his outspoken nature and his longstanding problem with alcohol abuse had discouraged teams from bringing him on.

“I was a drinker for 33 years,” Blefary told The New York Times. “I started when I was 18. By Triple-A, I was drinking hard liquor.” Blefary felt that he had been blackballed by baseball, but now he understood why. “In the big leagues, I was out of control.”

Just before those admissions, Blefary enrolled in the alcohol rehabilitation program prescribed by former major leaguer Sam McDowell, also an alcoholic. Prior to rehab, Blefary was consuming roughly a quart of whiskey a day.

Blefary completed the program successfully, but damage had already been done to his body. He suffered from pancreatitis, a disease brought upon by heavy use of alcohol.

On Jan. 28, 2001, Blefary died from the effects of pancreatitis. He was only 57 years old. When I heard the news, it hit me hard. Blefary had just come to Cooperstown for an autograph signing the year before. I had wanted to meet him, but for some reason, I didn’t make it to the signing. I thought to myself, “I’ll get him next year.” Next year would never come.

I regret never talking to Blefary about his fascinating and often difficult career. I missed out on hearing from the man who had roomed with Don Wilson, visited terminally ill children in the hospital, battled the effects of alcoholism and worked with the mentally challenged.

All that’s left for me is Curt Blefary’s baseball card – and the important memories that come with it. I guess that will have to do.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

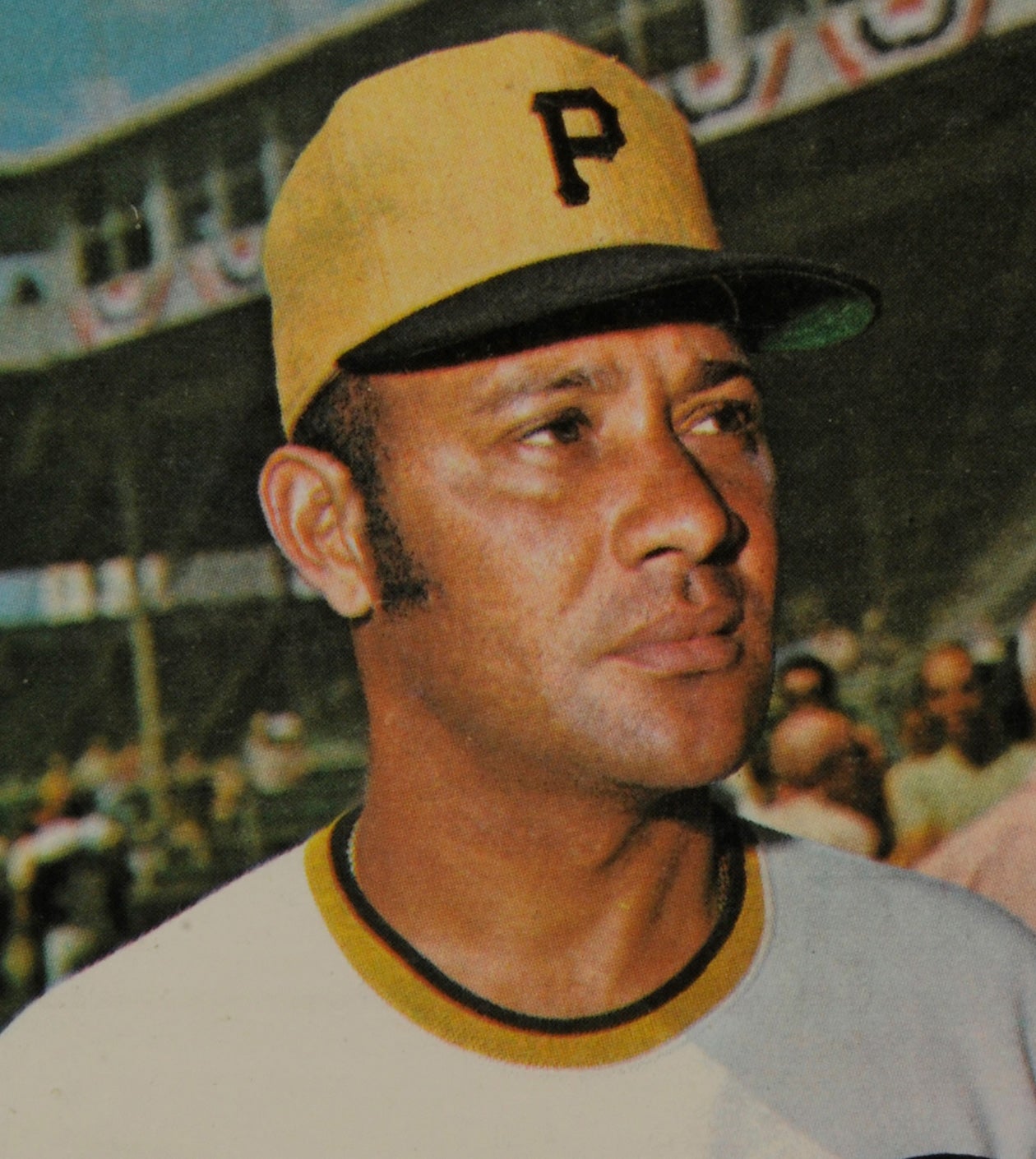

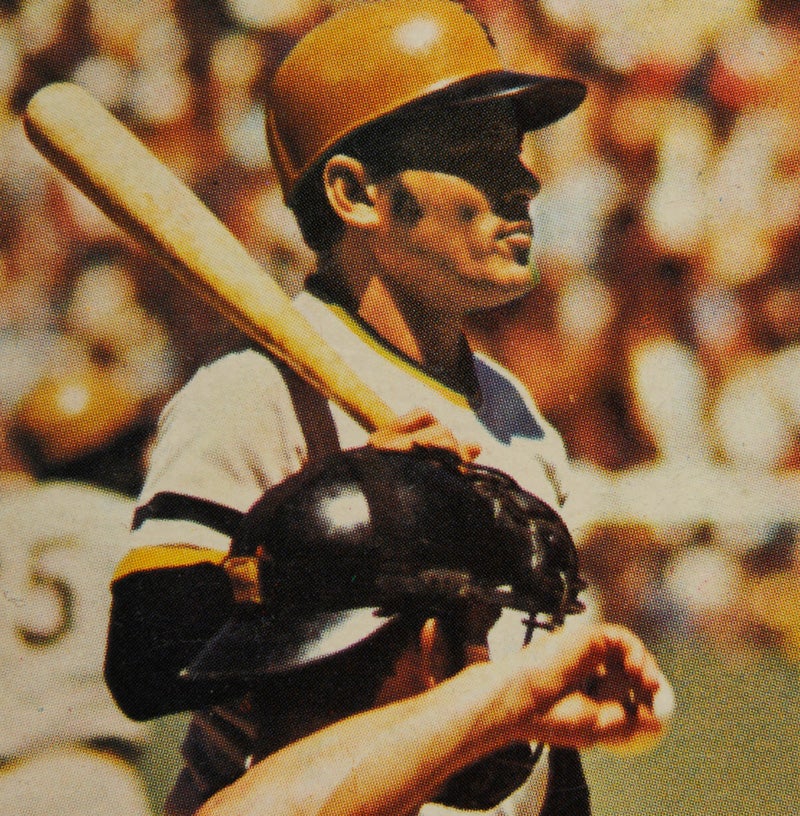

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

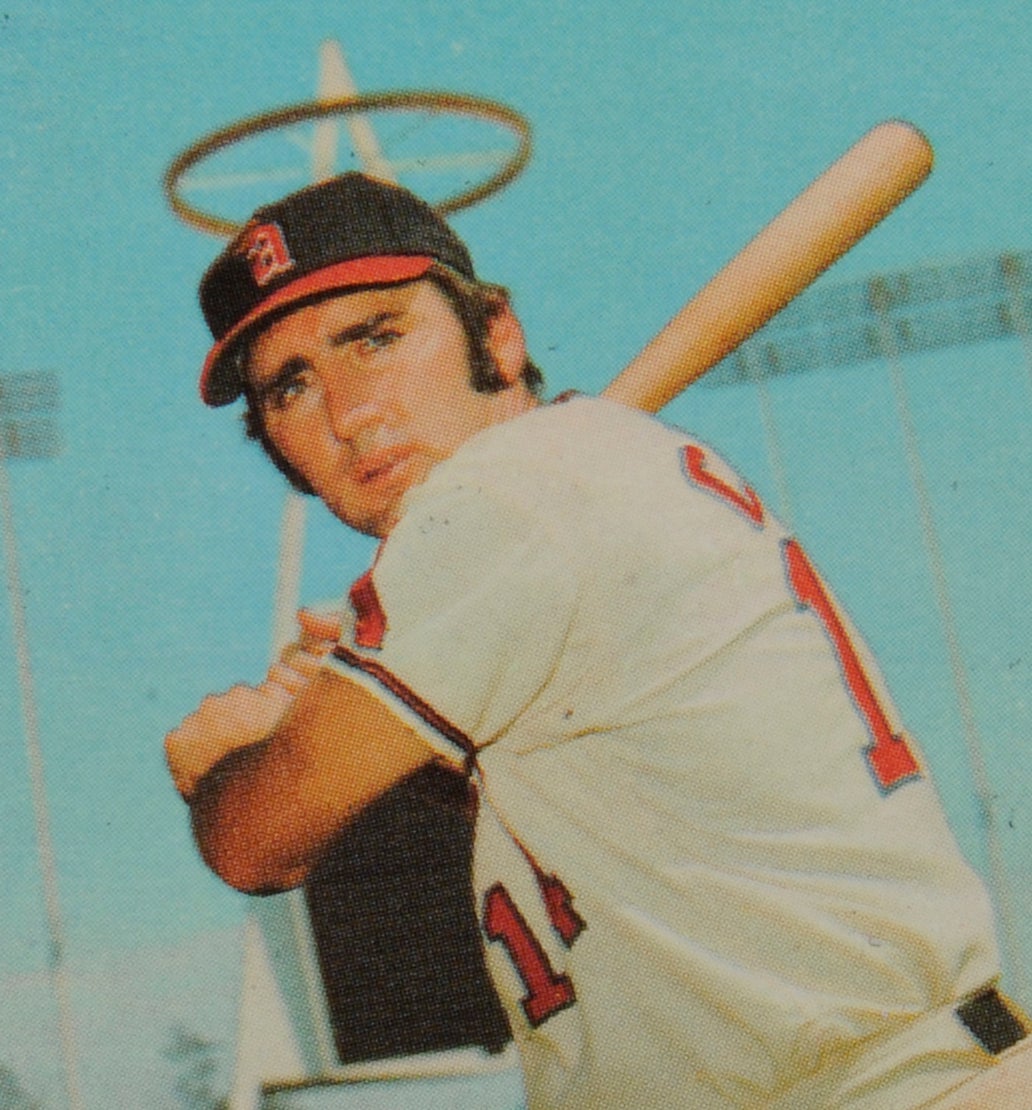

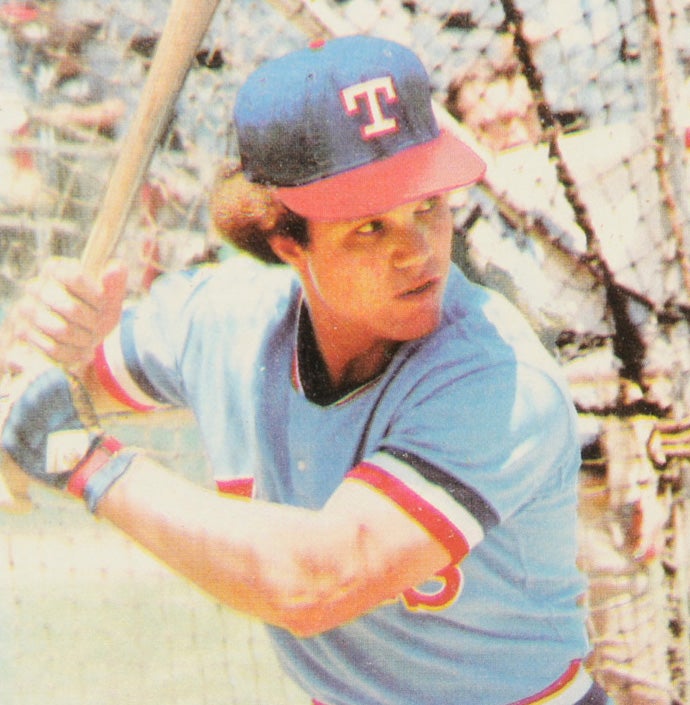

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan