- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1971 Topps Dave May

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Dave May

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

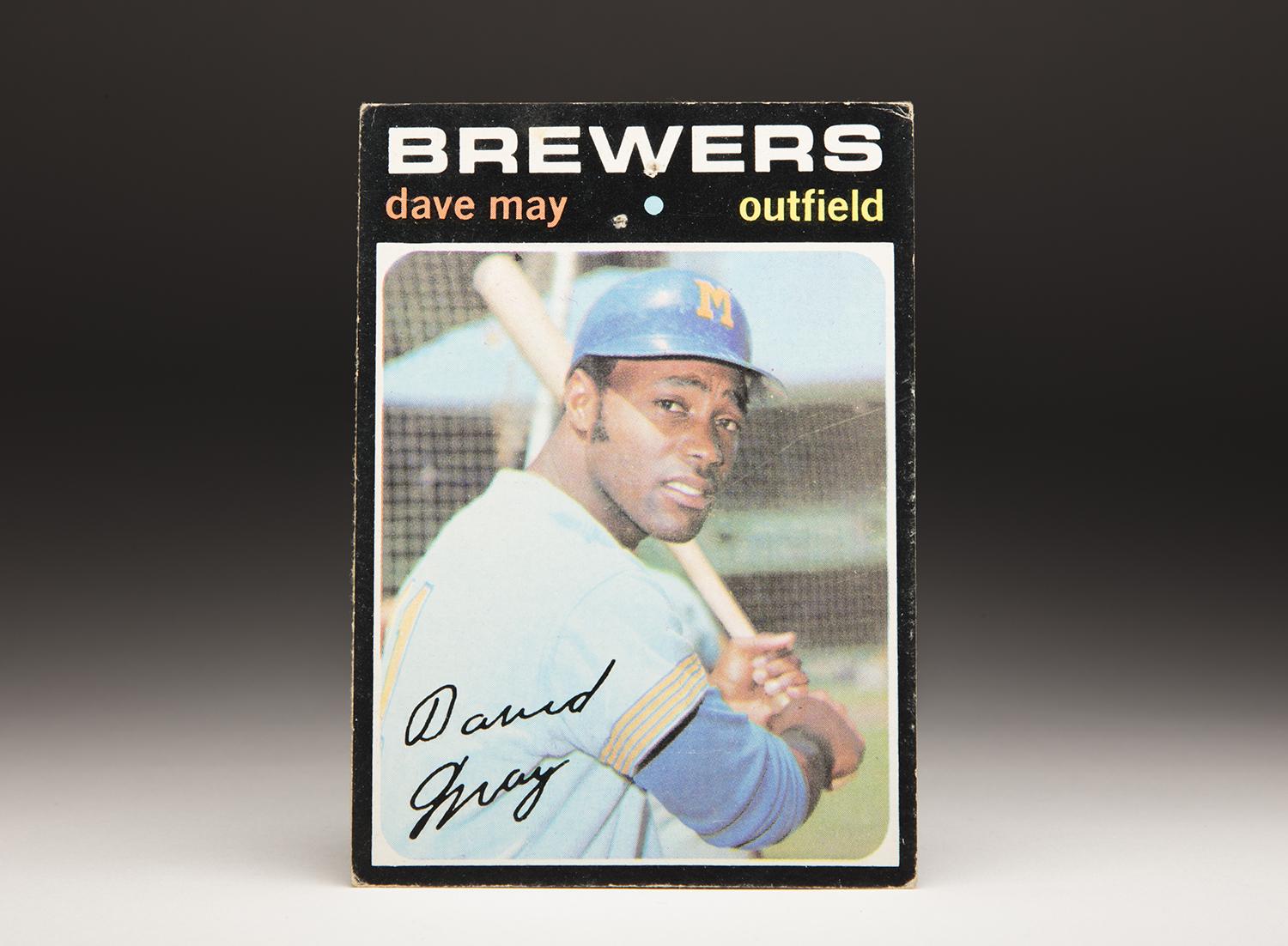

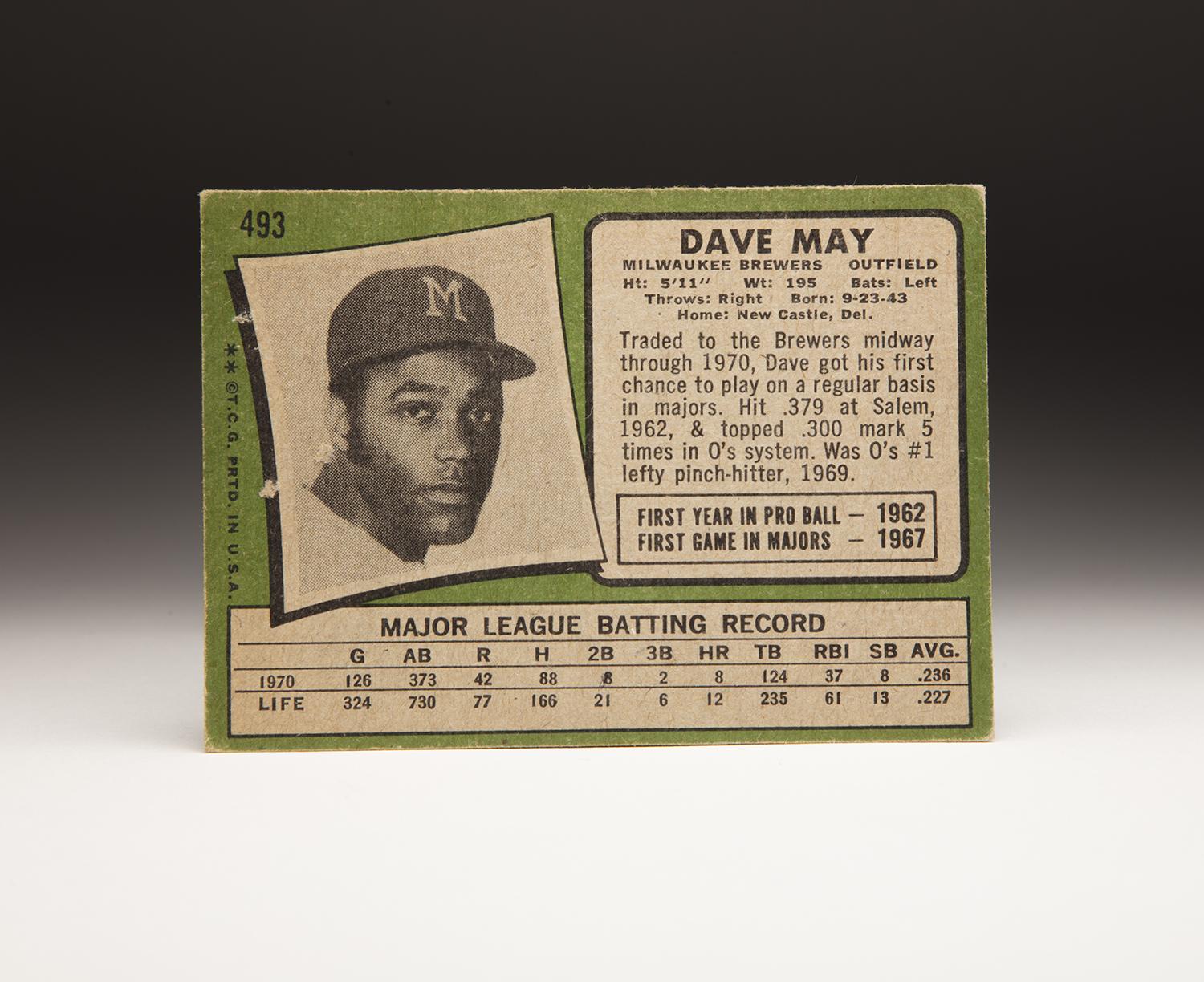

It’s no wonder that the 1971 Topps set has become a favorite among collectors of vintage cards. With those distinctive black borders, the solid photography, the introduction of action shots and that peculiar but eye-catching lower case font, the cards of 1971 always stand out – even when mixed with cards from other sets.

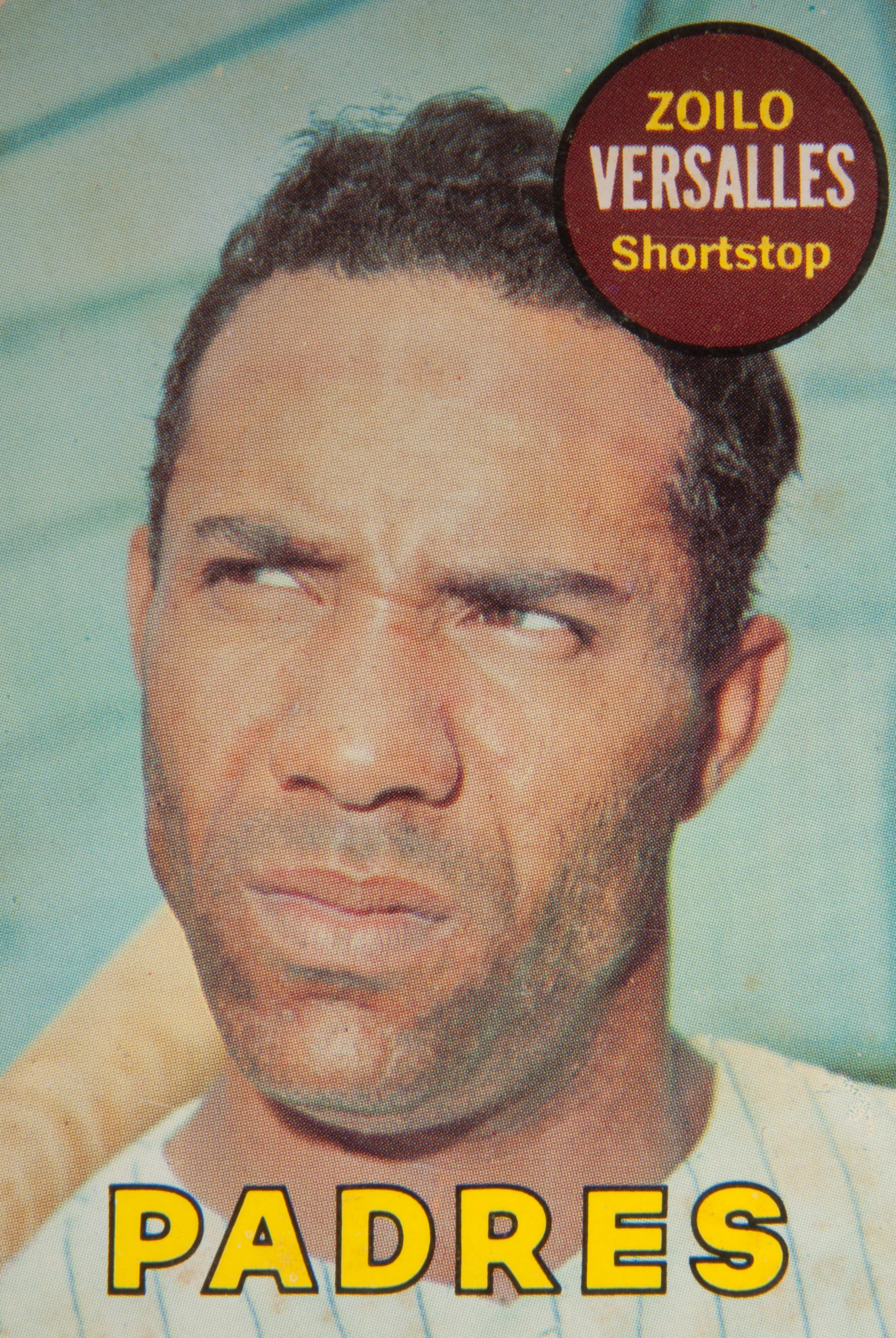

One of the best cards to be found in ’71 Topps is Dave May’s card, the first one to show him playing for the Milwaukee Brewers. It’s a posed shot, but one that gives us a good view of May, who always had that muscular, brawny build. Few players wore a uniform any better than May. I’m a particular fan of the Brewers’ early road uniforms, which essentially borrowed the style left behind the old Seattle Pilots. Those uniforms had an attractive light blue finish, which contrasted nicely with the succession of gold stripes near the sleeve. The slightly darker blue used for the undershirt and the helmet completed the picture nicely.

The 1971 card carries a special meaning for one of May’s sons, David Jr. “I think for me it was just the first time that I actually noticed my father was famous,” the younger May told me through Facebook. “Kids in kindergarten showed me this card the following year and asked if this was my dad. Until then, what he did – never really stood out.”

May’s career stood out for a number of reasons. For many years now, he has been remembered foremost as the man who was traded for Hank Aaron. It’s understandable that such a fact would stick with baseball fans, but there is a lot more to the Dave May story than just that.

On a personal level, I’ll always remember him as Davey May, not Dave May or David May, which is probably what he preferred, based on the way that he signed his 1971 Topps card. Davey May sounded more lyrical, more hip. For us fans growing up in the early 1970s, at least the guys that I hung around with, it was always Davey May. That was cool.

Davey May was also a good ballplayer. At 5-foot-10 and 185 pounds, he could hit, he flashed power, he ran well, and played a good outfield – whether it was in center field or right field. He was also an example of perseverance, a player who was blocked at so many turns in his early career, and easily could have given up the quest, but did not. Instead, he earned the reward of a big league job, resulting in a long career and a number of friends along the way.

In tracing May back to the early days of his career, he originally signed with the San Francisco Giants in 1961. Assigned to the low minors, he would never make it to San Francisco. At the time, the Giants had a collection of good young outfielders in their system, making it a less than ideal place for him to be. After the 1961 season, he became eligible for a draft called the first-year draft, which no longer exists. Minor league players with one year of experience could be selected, though the drafting team had to give up some money in the process. The Baltimore Orioles decided that May was worth the investment.

The Orioles’ decision to draft May was both good and bad for the young outfielder. On the one hand, the Orioles taught their minor leaguers the right way to play the game, instilling the fundamentals of defense, base running and bunting from the ground up. If you made the major leagues by going through the Baltimore farm system, you generally arrived as a fairly finished product, one who understood how to play the game.

There was a down side, too. Like the Giants, the Orioles had a deep farm system, one that was full of talented outfielders. Given their depth, they could offer no guarantee to May of a place on the major league roster.

Through no fault of his own, May remained in the minor leagues for five full seasons. He compiled some gaudy batting averages along the way, including .368, .335, and .317. Finally, the Orioles called on him in July of 1967. The Orioles’ manager and coaches immediately took note of his positive attitude, his upbeat nature, and his willingness to laugh and have fun.

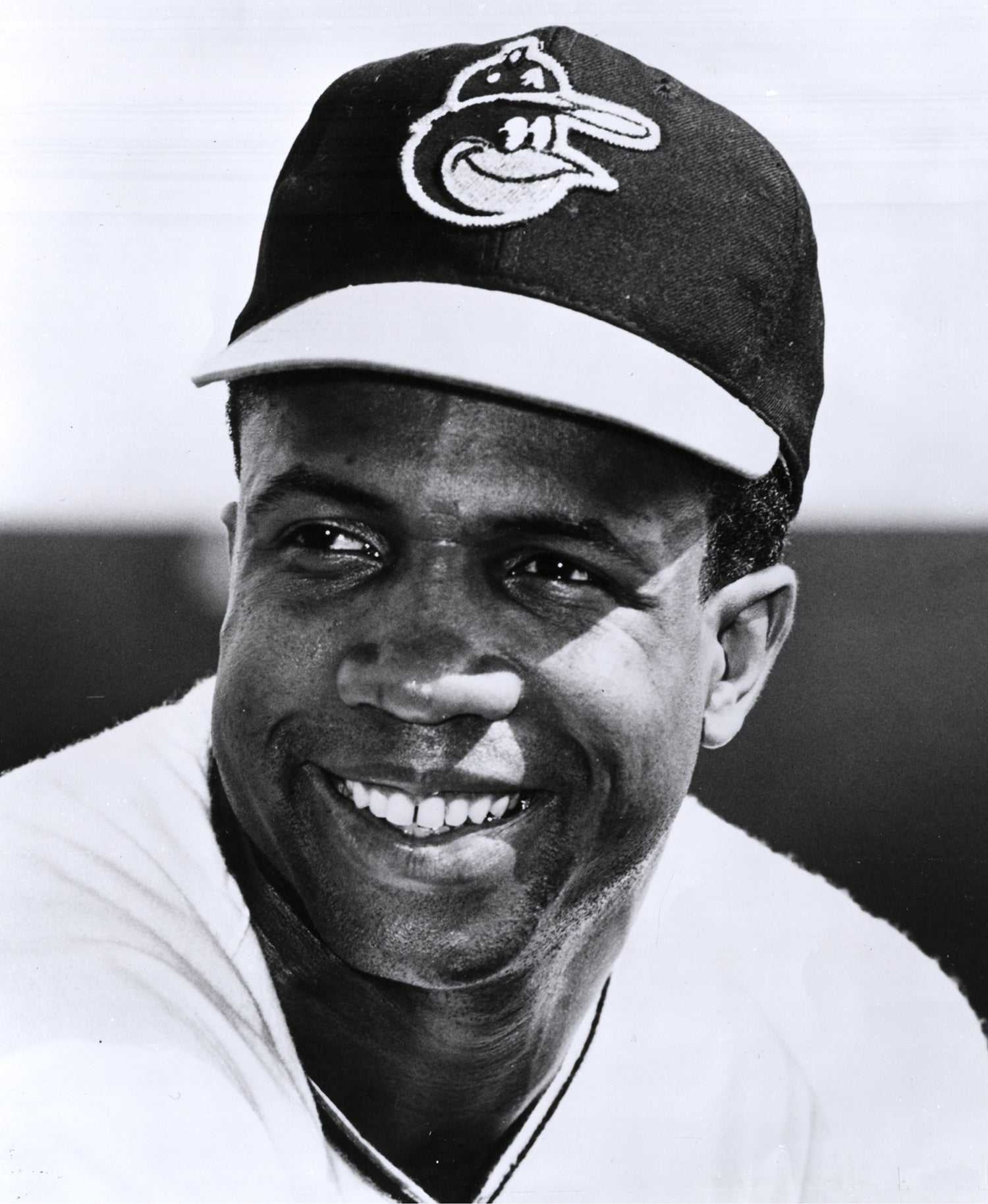

As a backup outfielder, May struggled to gain traction with the Orioles. In his first three seasons, he failed to hit higher than .242 and showed little power, making it difficult to earn a regular job on a team that had so many talented outfielders With established stars like Frank Robinson, Paul Blair and Don Buford, and young hopefuls like Curt Motton and Merv Rettenmund, there was little breathing room for May. Given such a blockade of talent, it became nearly impossible for May to find his timing and rhythm as a hitter.

The Orioles ran out of patience with May in the middle of the 1970 season. Struggling with a .194 batting average, he became trade bait. The O’s sent him to Milwaukee for pitchers Dick Baney and Buzz Stephen, denying him a chance at a World Series ring that October. But before leaving Baltimore, May traded his glove to teammate Brooks Robinson in exchange for five pairs of spikes and two other gloves. Preferring May’s glove, Robinson would use that one in stifling the Cincinnati Reds during the World Series and would later donate the glove to the Hall of Fame.

The trade to Milwaukee finally gave May the chance to play. The Brewers, playing their first season in Milwaukee after a failed debut as the Seattle Pilots, were thrilled to add a young talent like May, who was still only 26. In need of outfielders, the Brewers made May their starting center fielder and watched him play 100 games.

To their chagrin, May continued to struggle at the plate, hitting only .240 with a mere seven home runs. But his defensive play was something to behold, so good that it drew praise from manager Dave Bristol. “You don’t have to worry about balls hit in his direction. He’ll get anything that gets up into the air,” Bristol told the Sporting News. “I’m not looking for a center fielder anymore.”

May’s offense caught up to his fielding in 1971. A sturdily built left-handed hitter, May began to show the kind of power/speed combination the Orioles had forecast for him in the mid-1960s. He hit 16 home runs, stole 15 bases and reached base 34 percent of the time.

In 1972, American League pitchers seemed to figure out May’s weaknesses. His OPS fell off to a subpar .643. He ran the bases inefficiently, stealing 11 bases while being caught 13 times. He also had to deal with illness, which sidelined him for a while. Away from the playing field, May mourned the death of his father, making a bad season even more difficult.

Continuing his pattern of good season after bad one, May bounced back with a remarkable 1973, by far the best performance of his career. He clubbed 25 home runs, nine better than his next-best total, and batted .303, the only time in his career he bettered .300. He also tied for the American League lead with 295 total bases. May not only made the All-Star team, but he also placed eighth in the league’s MVP voting, especially impressive given that the Brewers were out of contention for most of the summer.

The Brewers hoped that May’s breakthrough would trigger stardom, but he returned to a pattern of inconsistency in 1974. Enduring a bout with the flu during Spring Training, May found himself sapped of much of his energy. And then, only one week into the regular season, Bristol switched May from center field to right field.

That move did not sit well with May. Perhaps distracted by his switch in positions, May struggled so much that his OPS dipped below .600. After the season, the Brewers saw a chance to move May in exchange for a brand name player. They sent May and minor league left-hander Roger Alexander to the Atlanta Braves for Hall of Famer and newly crowned home run king Hank Aaron. Aaron hoped to extend his career as a DH in the American League, and also sought the comfort of playing in Milwaukee, where he had starred for so many years. As for the Braves, they realized that May was still only 31 and might benefit from playing at Fulton County Stadium, known as “The Launching Pad” because of the number of home runs hit there.

May welcomed the news of a change in venue. “I didn’t ask to be traded,” he told the Chicago Defender. “[Still], I felt a trade was necessary and would help me out. Of course, there was an extra thrill involved in being traded for Hank Aaron.”

The Braves used May as a platoon player in right field, severely limiting his at-bats against left-handed pitching. He also suffered through a string of injuries that curtailed his playing time. By season’s end, May played in only 82 games and accumulated a mere 230 plate appearances. But when he did play, hit very well. At season’s end, he posted an on-base percentage of .361 and a slugging percentage of close to .500.

Then came another off season in 1976, sustaining the pattern of inconsistency. That winter, the Braves made May part of a blockbuster trade with the Texas Rangers. The Braves sent May, fellow outfielder Ken Henderson, and pitchers Roger Moret, Carl Morton and Adrian Devine to the Rangers for star right fielder Jeff Burroughs, who had been named American League MVP only two years earlier.

As a platoon right fielder with the Rangers, May struggled, hitting .241 with only seven home runs. Then came the 1978 season, which found May caught in a difficult situation. The Rangers included him on their Opening Day roster, but a crowded outfield resulted in no playing time to start the season. He then suffered a shoulder injury, which mandated a trip to the disabled list. After being reactivated in mid-May, and without having appeared in a single game for the Rangers that spring, they sold him to the Brewers in a straight cash deal. Playing in a utility outfield role, May didn’t hit at all, prompting the Brewers to sell his contract to the Pittsburgh Pirates in September. He appeared in five games for the Pirates and then drew his release that winter, preventing him from becoming a part of the Bucs’ world championship team in 1979.

Rather than retire, May accepted a Spring Training invite from the Philadelphia Phillies. He reported to their spring camp, but failed to make the Opening Day roster. Still wanting to play, May sought employment in the minor leagues. He signed on with the fledgling Inter-American League, an independent Triple-A league that featured teams in the United States and throughout Latin America. May played for the Santo Domingo Azucareros (or Sugarmakers), who were managed by former major league pitcher Mike Kekich. May played respectably in 44 games, but endured a whirlwind of consternation as the league struggled through bad weather, horrid playing conditions and financial hardships. In midseason, the bankrupt Inter-America League folded up shop, leaving a disgusted May without a job and signaling the end of his long career in professional baseball.

With his playing career over, May returned to Delaware, where he played semipro ball and sold furniture. In 1983, he returned to Organized Baseball as a hitting instructor with the Braves, but soon returned to furniture and home appliance selling. He later became the director of a recreational sports site.

Sadly, May’s health took a turn for the worse in 2003, when he was diagnosed with diabetes and doctors determined that his right leg needed to be amputated. For the remainder of his life, he struggled with his health. In October of 2012, he passed away at the age of 68.

Although Dave May was essentially a journeyman outfielder, he had a huge impact on the game, even after his playing days. His daughter, Denae, became a standout softball player in high school. Two of his sons found success in baseball. One of them, Derrick May, played for the Chicago Cubs and a few other teams in the 1990s. Appropriately, Derrick finished his playing days with the Orioles, the same organization where Dave began his major league career. His other son, the aforementioned David Jr., has enjoyed a substantial career as a big league scout with Toronto and Seattle. Thankfully, the wonders of Facebook have allowed me to get to know both of the sons a bit better, even though I have never met them.

Once described by the Dallas Morning News as “one of the friendliest players in the sport,” Dave May made countless friends during his stops in Baltimore, Milwaukee, Atlanta, Texas and Pittsburgh. Just consider what Derrick said in describing the number of phone calls his father received while living out his final days in New Castle, Del. “I never realized how many people he’s impacted, not only around here but people in baseball,” Derrick told Delaware Online. “Dusty Baker called, and Cito Gaston, Willie Horton, Ralph Garr, and all these people called just to help him out. He and Johnny Briggs [his teammate in Milwaukee] were best friends for 40 years.”

Yes, he was once traded for Hank Aaron, but that happenstance ranks well behind his many accomplishments within the game. In helping his teams win, making friends, and leaving behind a good family, the late Dave May forged the strongest of legacies.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

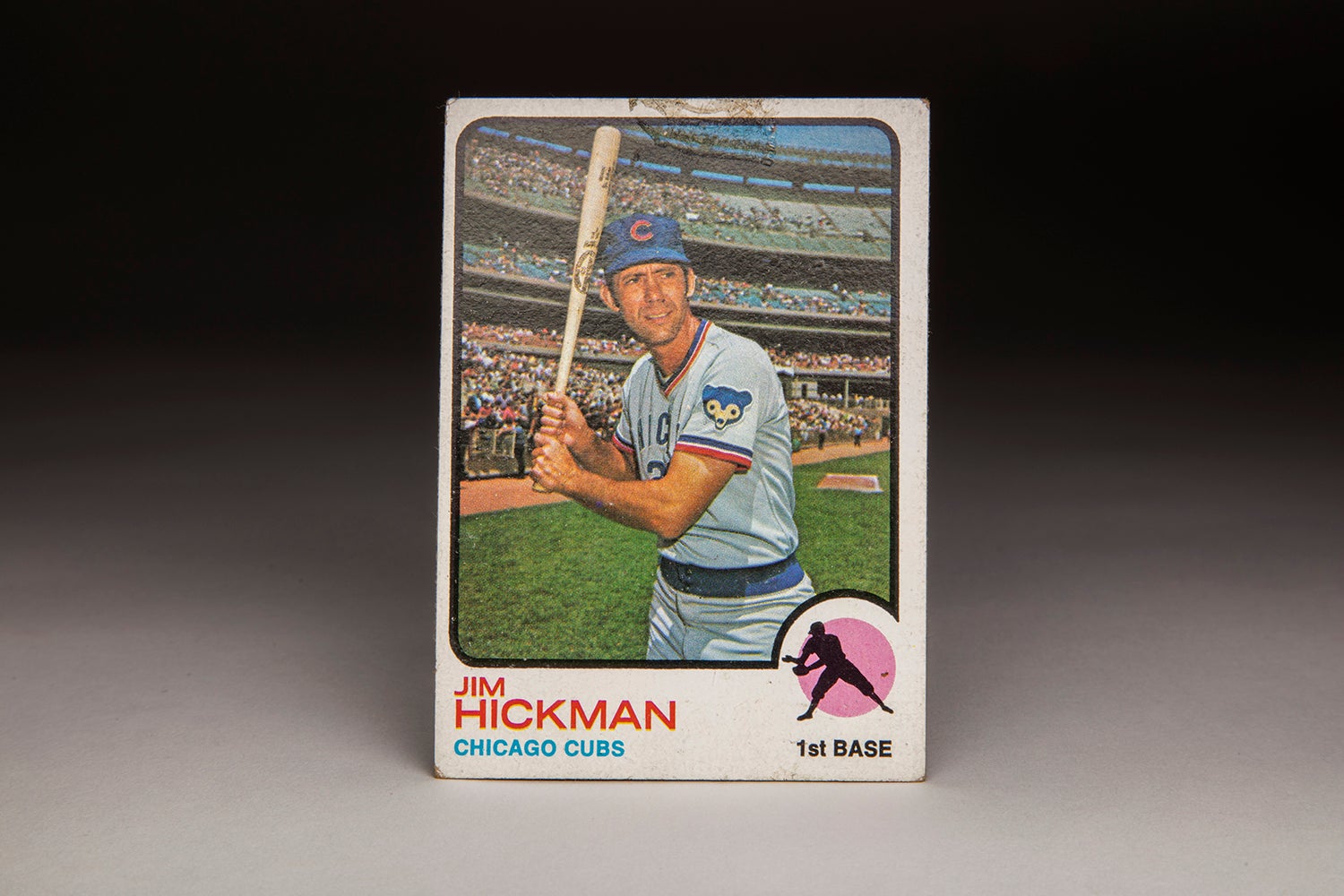

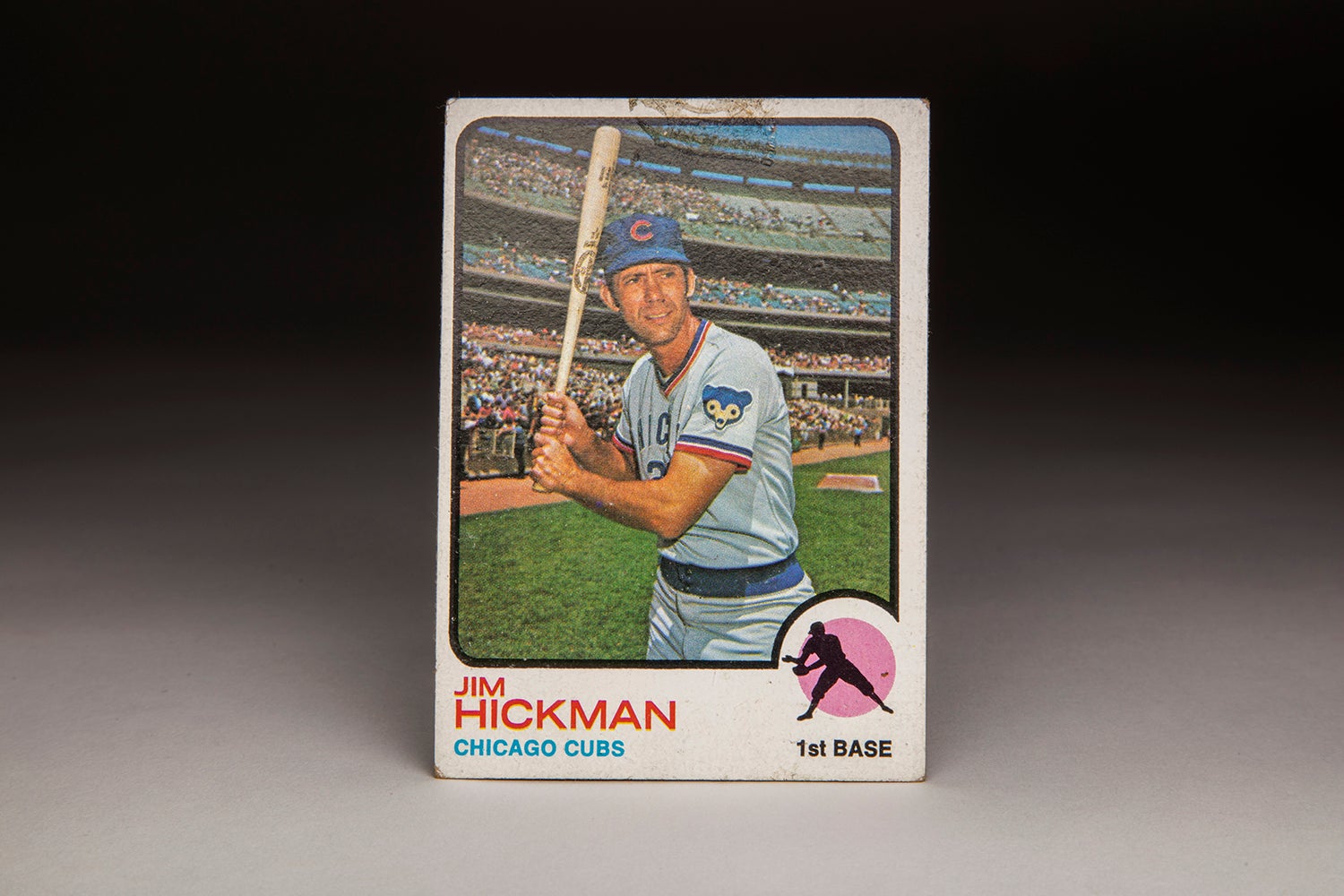

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

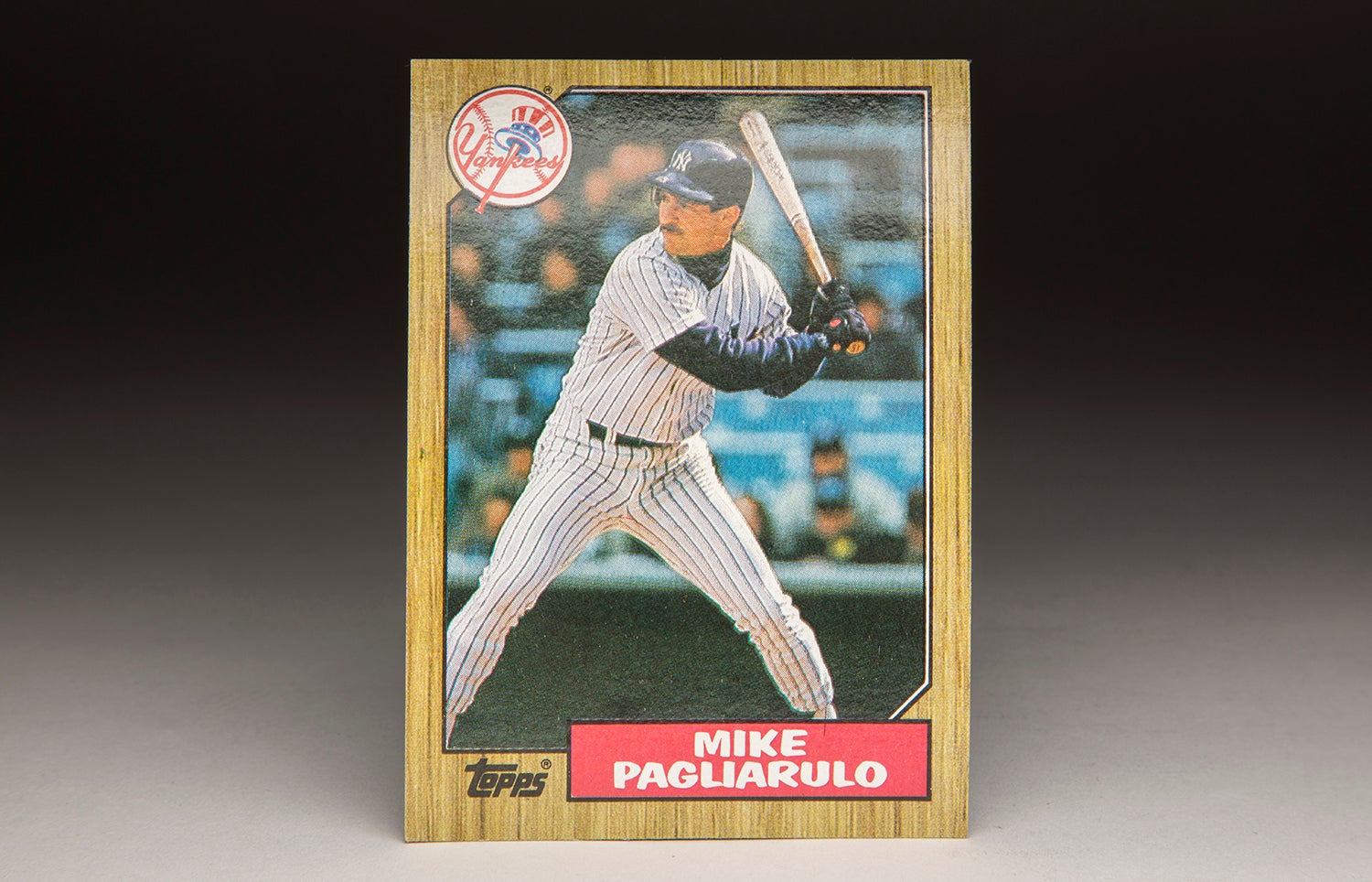

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Pagliarulo

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman