- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1976 Topps Juan Beníquez

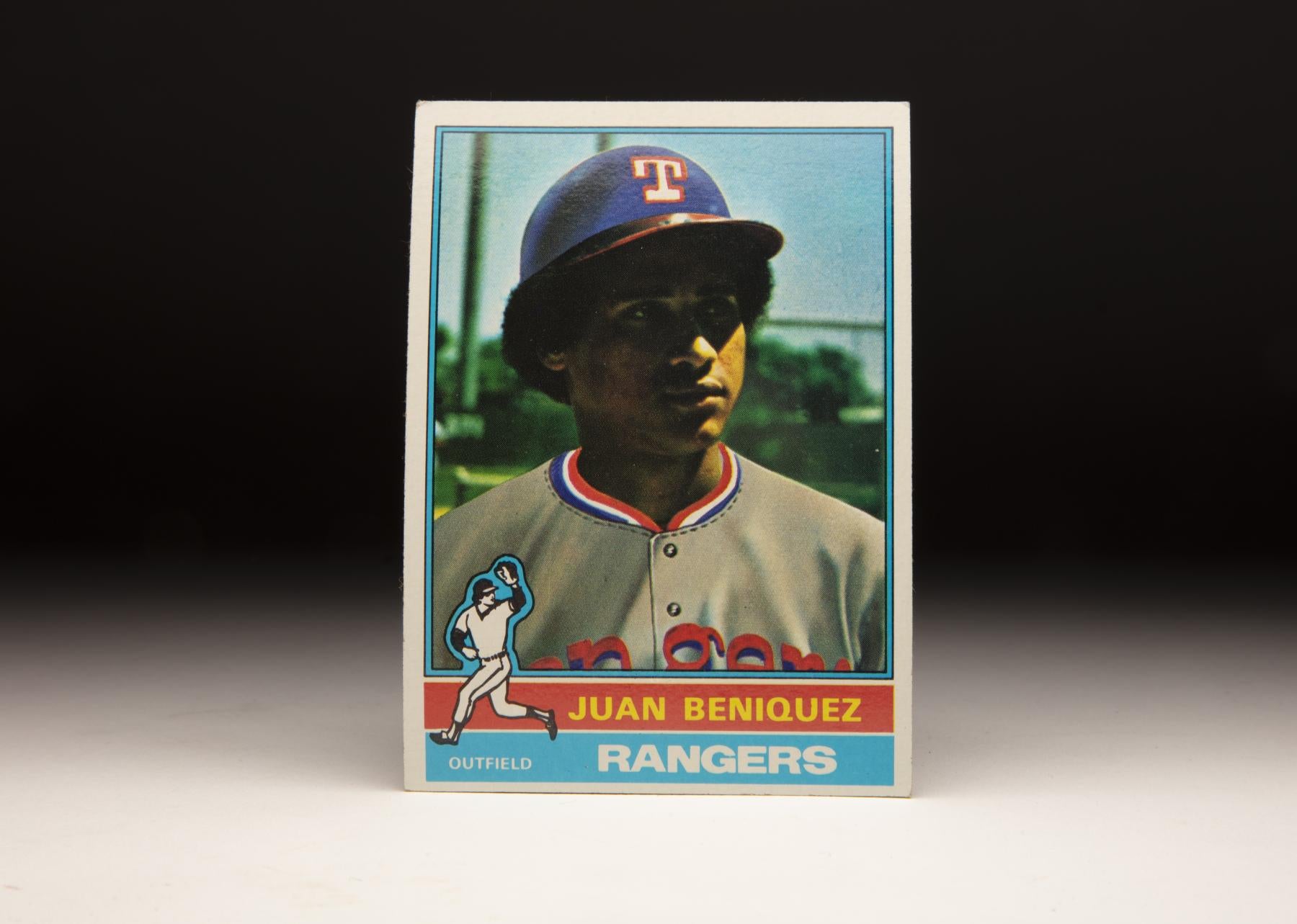

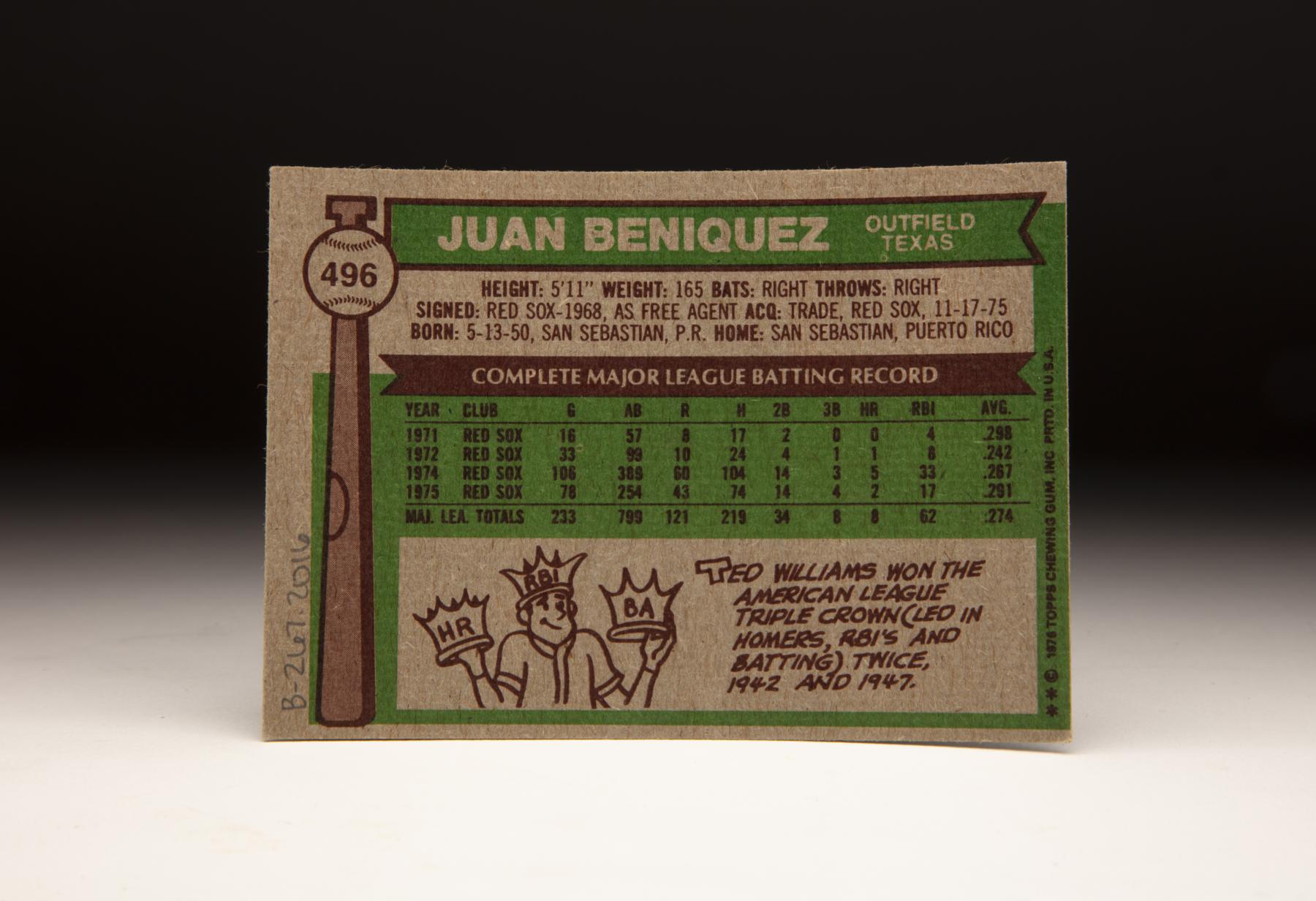

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Juan Beníquez

In the first decade of MLB free agency, Juan Beníquez set a record for playing with eight different American League teams – a total that seems rather small by today’s standards.

But for Beníquez, it represented a career that saw him transition from defensively-challenged shortstop to a field-first outfielder and then a quality bench bat while he visited the majority of the AL outposts.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Born May 13, 1950, in San Sebastian, Puerto Rico, Beníquez started in youth baseball at age 10 as a pitcher. By his mid-teens, Beníquez had become an infielder and was drawing notice in the Puerto Rican amateur leagues.

On Oct. 1, 1968, Beníquez was signed to the Red Sox by scout Pedro Vazquez. He reported to Winter Haven of the Florida State League in 1969, where he hit .261 with 59 RBI, 16 steals and 78 walks while committing 49 errors over 603 chances at shortstop.

Beníquez was promoted to Winston-Salem of the Class A Carolina League late in the 1969 season, and he returned to Winston-Salem in 1970.

“Beníquez will be the next shortstop at Boston,” Winston-Salem manager Bill Slack told the Winston-Salem Journal. “He has all the tools to do the job.”

Beníquez hit .272 with 30 stolen bases in 92 games for Winston-Salem in 1970 before moving up to Double-A Pawtucket. He finished the season batting .262 with 13 homers and 43 steals – but also had 64 errors in 755 chances at short for a fielding percentage of .915.

“I figure it will take me about two years to get to the major leagues,” Beníquez told the Winston-Salem Journal in 1970.

Beníquez proved to be quicker than he expected. He played most of the season with Triple-A Louisville, hitting .279 with 16 triples and 30 stolen bases while cutting his errors to 55. On Sept. 4, 1971, Beníquez made his big league debut, replacing Luis Aparicio at shortstop for the Red Sox in the eighth inning of a game against Cleveland at Fenway Park. Beníquez hit .298 in 16 games for the Red Sox that September, then returned to Louisville to start the 1972 season. After another strong performance at the plate in Triple-A, Beníquez was brought up to Boston in June when Aparicio went on the disabled list with a broken finger.

But while Beníquez was able to adjust to big league pitching, his fielding woes continued. He set an unwanted American League record with six errors over two games July 13-14. His playing time decreased when Aparicio returned in August and finished the year with a .242 batting average and 14 errors over 33 games with Boston.

The Red Sox brought Aparicio back for the 1973 season and sent Beníquez to Triple-A Pawtucket, where he transitioned to the outfield while leading the International League with a .298 batting average. He won the job as the Red Sox Opening Day center fielder in 1974 and appeared poised for a promising career in Boston.

“The kid is a natural hitter,” Red Sox manager Darrell Johnson told the Associated Press in the spring of 1974. “He makes solid contact with the ball consistently. He can go and catch the ball. He just has to get fundamentals down pat.”

But Beníquez soon was caught in a talent squeeze as the Red Sox were churning out prospects at a phenomenal pace. Beníquez began splitting time in center field with Rick Miller, a superior defender but a lesser hitter. With young Dwight Evans in right field and future stars Fred Lynn and Jim Rice burning up the minors, Beníquez’s future in Boston was cloudy.

“I don’t care where I play – center, right, left, third, just as long as I play,” Beníquez told the AP. “That’s the only thing that matters.”

Beníquez appeared in 106 games for Boston in 1974, hitting .267 with 19 stolen bases. But in 1975, Lynn took over the center field job with a season for the ages, and Rice started the majority of the team’s games in left. With veteran Rico Petrocelli at third base and Evans in right field, Beníquez appeared in only 78 games – hitting .291 off the bench to help the Red Sox win the American League East.

But with Rice sidelined with a broken hand suffered in September, Beníquez was tabbed by Johnson as the team’s designated hitter during the ALCS vs. Oakland. Beníquez responded with three hits in 12 at-bats for a .250 average, including a 2-for-4 performance in Game 1 that saw him single home a run and also score in a five-run seventh inning that turned a 2-0 Boston lead into a 7-0 advantage.

The Red Sox swept the Athletics to advance to the World Series. But by rule, the 1975 Fall Classic did not feature a designated hitter in any game (the World Series employed alternating years with the DH from 1976 until 1986, when the DH began being used every year in games hosted by the AL pennant winner), leaving Beníquez without much playing time.

He started Game 4 and Game 5 in left field and entered Game 7 as a pinch hitter in the bottom of the ninth, going 1-for-8 overall as the Reds defeated the Red Sox in seven games.

On Nov. 17, 1975, the Red Sox traded Beníquez, Steve Barr and Craig Skok to the Rangers in exchange for future Hall of Famer Fergie Jenkins.

On the first day of Spring Training in 1976, Rangers manager Frank Lucchesi told Beníquez that he would be his regular center fielder.

“Never before has anyone told me anything like that,” Beníquez said that spring. “It makes me feel comfortable. This is a big chance for me.”

True to his word, Lucchesi started Beníquez in center field on Opening Day and kept him in the lineup all season. Beníquez did not hit for power – slugging just .301 in 145 games – but stolen 17 bases and hit a respectable .255. He also led all AL outfielders in putouts (410) and assists (18).

Beníquez was the Rangers’ center fielder again in 1977, and with the pitching pool watered down due to the debut of expansion teams in Toronto and Seattle, offense was up throughout baseball that year. Beníquez was hitting .289 in late July when a hamstring pull sidelined him, and he ran afoul of Rangers manager Billy Hunter Aug. 31 when he was caught stealing in the ninth inning of a one-run game.

“Juan Beníquez probably has as much ability as any player on this club,” Hunter told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “But he hasn’t played that much in the major leagues. He needs direction, and this is what I want to give him. If Juan Beníquez will accept this direction, he can be my center fielder. If he can’t, someone else will be.”

Beníquez finished the season with a .269 batting average, 10 homers, 50 RBI and 26 steals in 123 games. He also won a Gold Glove Award – likely a result of his superior 1976 season defensively as his numbers in 1977 were not as strong.

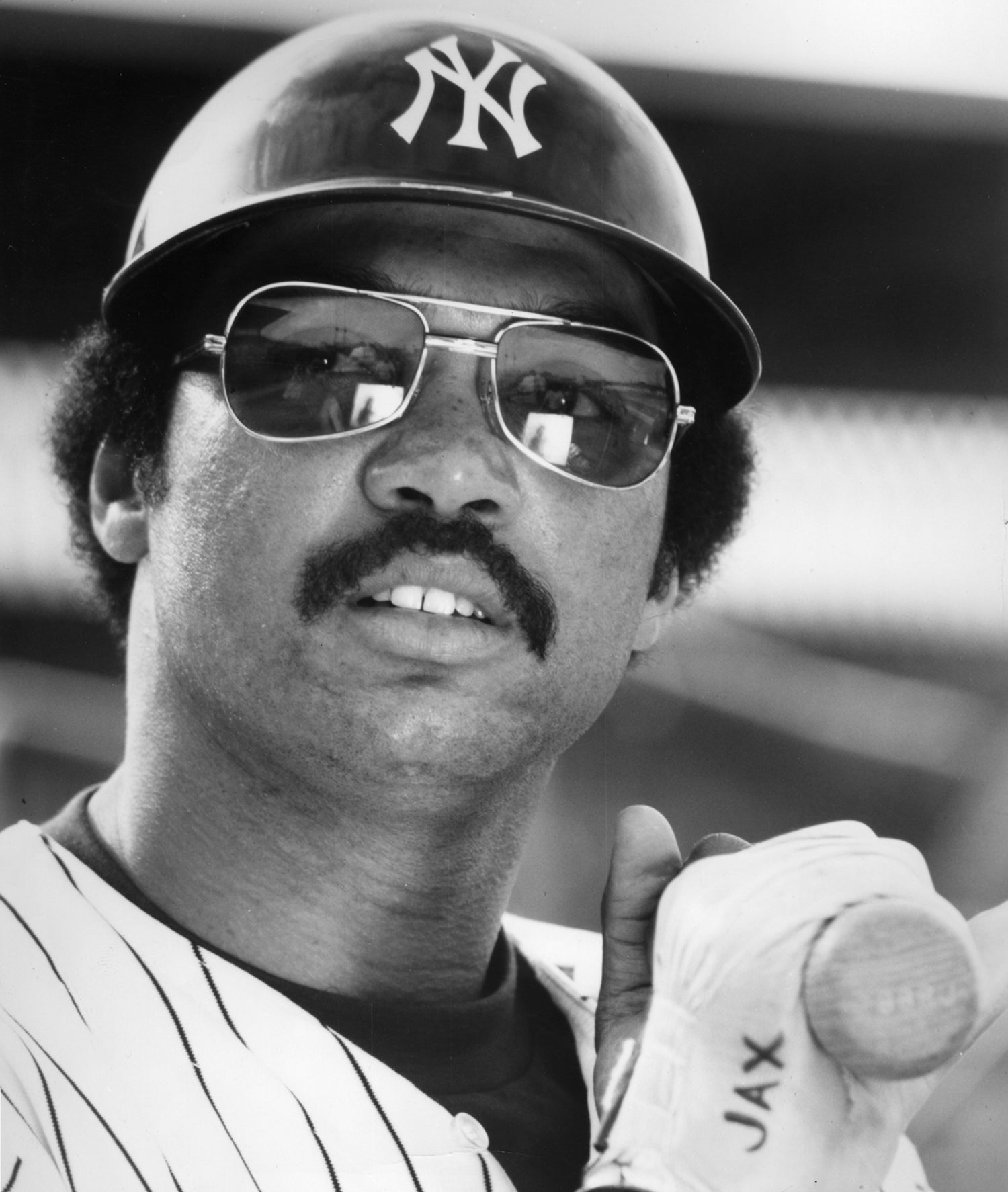

Beníquez posted similar numbers in 1978, hitting .260 with 11 homers and 50 RBI in 127 games as Texas’ everyday center fielder. But with the club coming off a 94-win campaign and expected to contend for the pennant, the Rangers battled internal issues and finished second in the AL West with 87 victories. Management decided changes were in order and executed several large trades following the season, including a deal that sent Beníquez and four others – including prospect Dave Righetti – to the Yankees in exchange for a package that brought Sparky Lyle to Texas.

But Beníquez’s 1979 season was beset by injury as he broke a finger in his first at-bat of the exhibition season, missed time with a sprained thumb and then had to be carted off the field with a groin injury suffered running the bases on July 31. He appeared in just 62 games, hitting .254 before being traded to the Mariners on Nov. 1 in another multi-player deal that brought Ruppert Jones to New York.

For the second straight season, however, Beníquez suffered an injury during an exhibition game – this time dislocating his right shoulder after a fall running the bases March 25 against the Athletics in Scottsdale, Ariz. The injury kept him sidelined until June, and he also missed time with a hamstring injury.

After his return, Beníquez was suspended on Sept. 1 following an incident in that night’s game against Baltimore when Mariners manager Maury Wills said Beníquez refused his request to pinch hit in the ninth inning.

“I have talked to him like a brother, like a father, like a friend,” Wills told the AP. “I can’t do any more. I can’t go further with him or I’ll lose the rest of the club.”

Wills indicated he wanted Beníquez suspended for the rest of the season but Beníquez returned to the team a week later. He finished the season batting .228 in 70 games – but that didn’t dampen his value on the open market, as demonstrated when he became a free agent and the Angels signed him to a three-year deal on Dec. 29, 1980.

“I always thought Beníquez was one of the better center fielders in the American League,” Angels general manager Buzzie Bavasi told United Press International. “We’re trying to strengthen our defense up the middle and…we feel we’ve made excellent progress.”

Later that offseason, however, Beníquez found himself in a familiar situation as Fred Lynn once again took his job. The Angels traded for Lynn after the Red Sox got into a contract dispute with their All-Star center fielder, and Beníquez was once again relegated to bench duty.

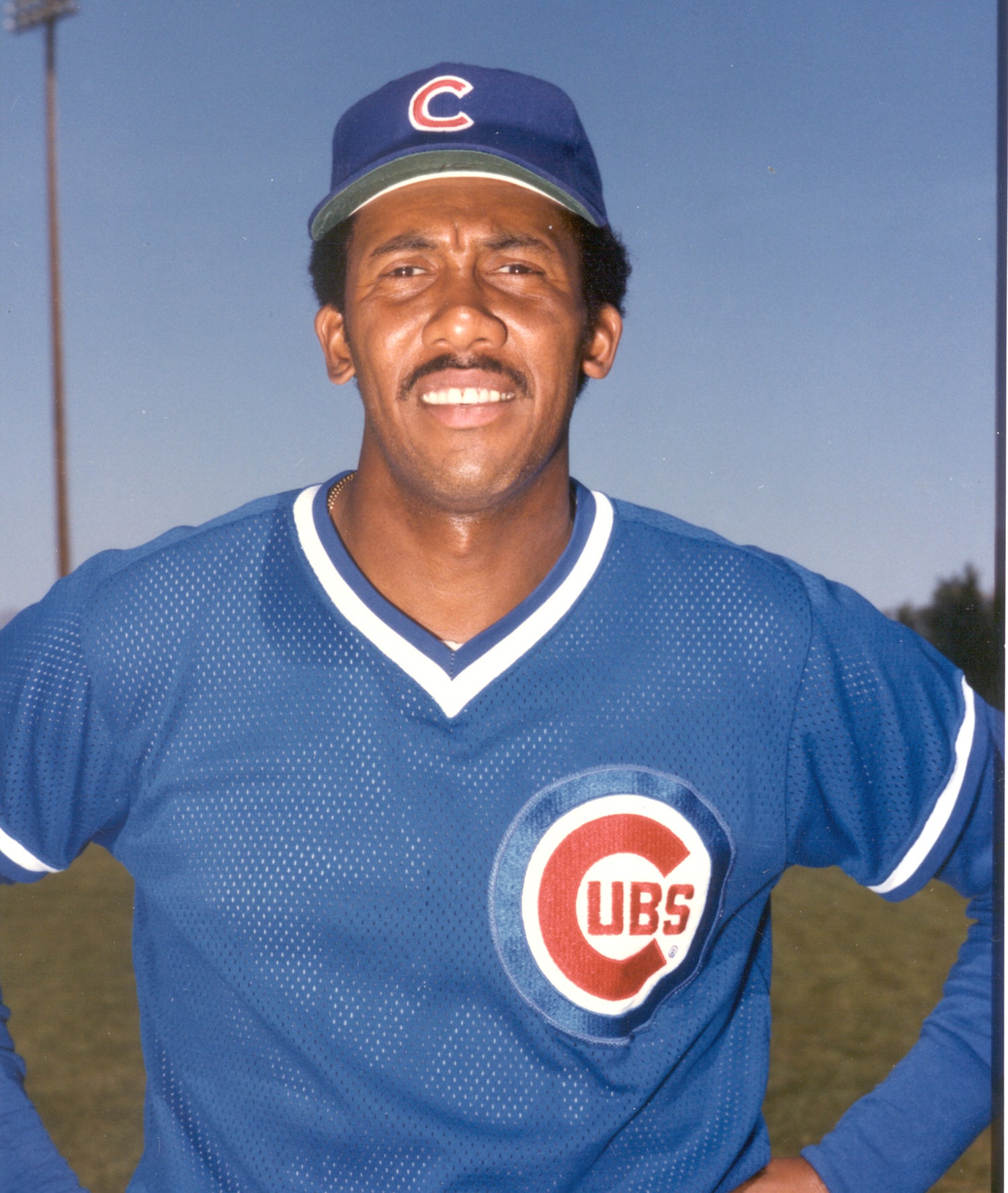

Serving as California’s fourth outfielder, Beníquez hit .181 in 58 games. But starting in 1982, Beníquez – now in his age-32 season – became one of the best backup outfielders in the game. He helped the Angels win the AL West in ’82, hitting .265 in a reserve role while serving as a regular late-inning defensive replacement for Reggie Jackson and Brian Downing. Then in 1983, Beníquez hit .300 for the first time, batting .305 over 92 games.

“When I first came up with Boston, I did not like not being an everyday player,” Beníquez told the AP. “But now, I can take it.”

The Angels extended Beníquez’s contract by two years after that season, and Beníquez was even better in 1984, hitting .336 and even drawing some support in the AL Most Valuable Player voting. He hit .304 in 132 games in 1985, seeing substantial time at first base as the Angels worked to get his bat into the lineup.

A free agent once again, Beníquez turned down a one-year, $500,000 offer from the Angels. But the best he could find elsewhere was a one-year, $450,000 deal from the Orioles.

“I think Juan is the kind of player who is more valuable to a contender,” Orioles manager Earl Weaver told the Fort Lauderdale News. “He could be the one man to put us over the top.”

Beníquez didn’t lead the Orioles to the postseason but did hit .300 in 113 games, his fourth straight year reaching the .300 mark. Baltimore traded him to the Royals for two minor leaguers following the 1986 season, and Beníquez hit .236 before being dealt to Toronto on July 14. With the Blue Jays, Beníquez hit .284 for a team that led the AL East for virtually the entire season before the Tigers swept Toronto in the final series of the year to capture the division title. Beníquez was the DH in two of those three games, going hitless as Toronto lost each game by one run.

Beníquez was hitting .293 off the bench in 1988 when the Blue Jays released him on May 31.

“I did exactly what they were asking,” a disappointed Beníquez told the Canadian Press after his release. “I did exactly what I was doing for them last year.”

Beníquez would not play in the big leagues again, though he did appear in games with the Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1989. He finished his big league career with a .274 batting average, 1,274 hits and 104 steals in 1,500 games. At the time of his retirement, only five Puerto Rican-born players had appeared in more big league games.

“All my career people have ignored me,” Beníquez said toward the end of his playing days. “No matter what I’ve done, I’ve always had to worry about making the team during the spring.

“It’s taken me a long time to learn to hit. Early in my career, I was a dumb kid who always went up to the plate looking to knock it out of the park. Now, I do what the situation calls for. That comes with age.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1983 Donruss Fred Lynn

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bob Stanley

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Bob Boone

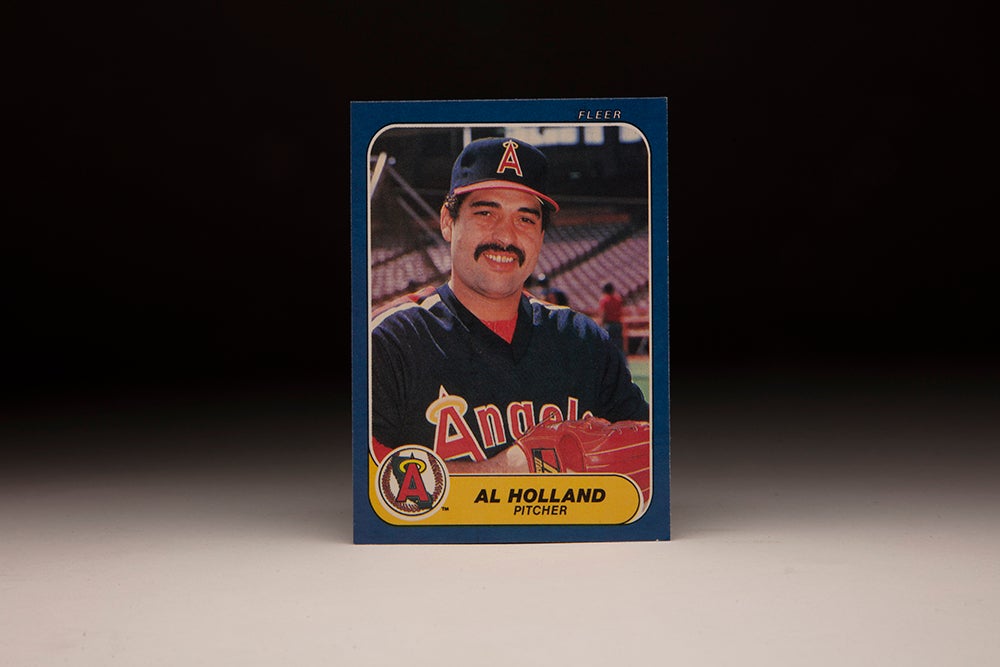

#CardCorner: 1986 Fleer Al Holland

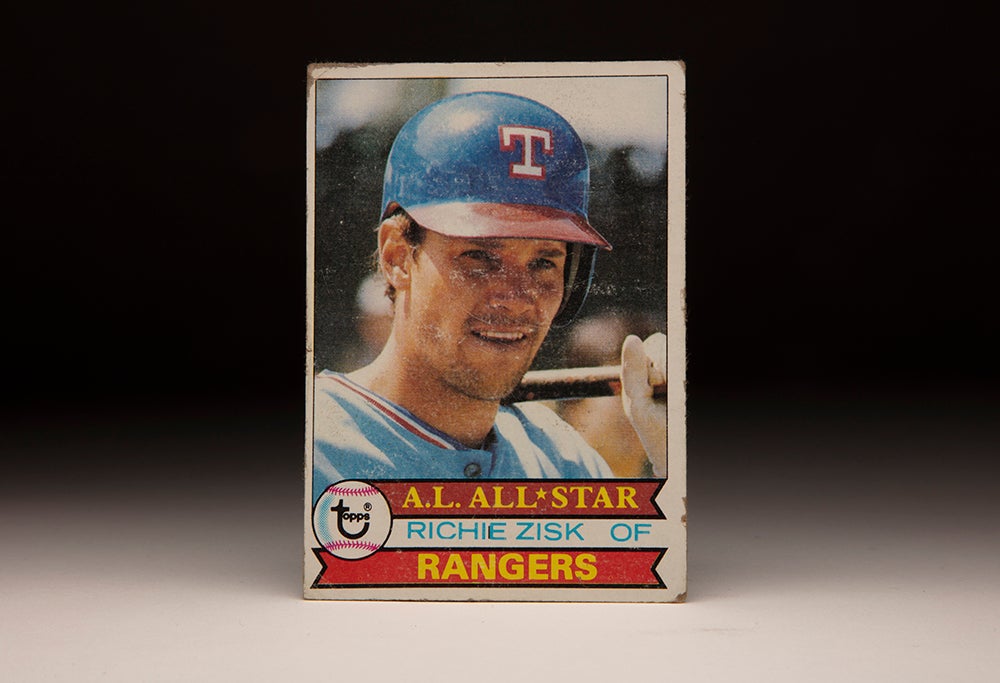

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Richie Zisk

Related Stories

High and Low Draft Roads Lead to Cooperstown

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Juan Beníquez

1975 Hall of Fame Game

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers Returns to Cooperstown to Host Otesaga Hotel Seniors Open Pro-Am Sept. 6

Induction Eve Thrills Fans, Hall of Famers in Cooperstown

Draft Records in Cooperstown

1975 Hall of Fame Game

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Juan Beníquez

Museum Partners with Artist Bill Purdom for 75th Anniversary Artwork

01.01.2023