- Home

- Our Stories

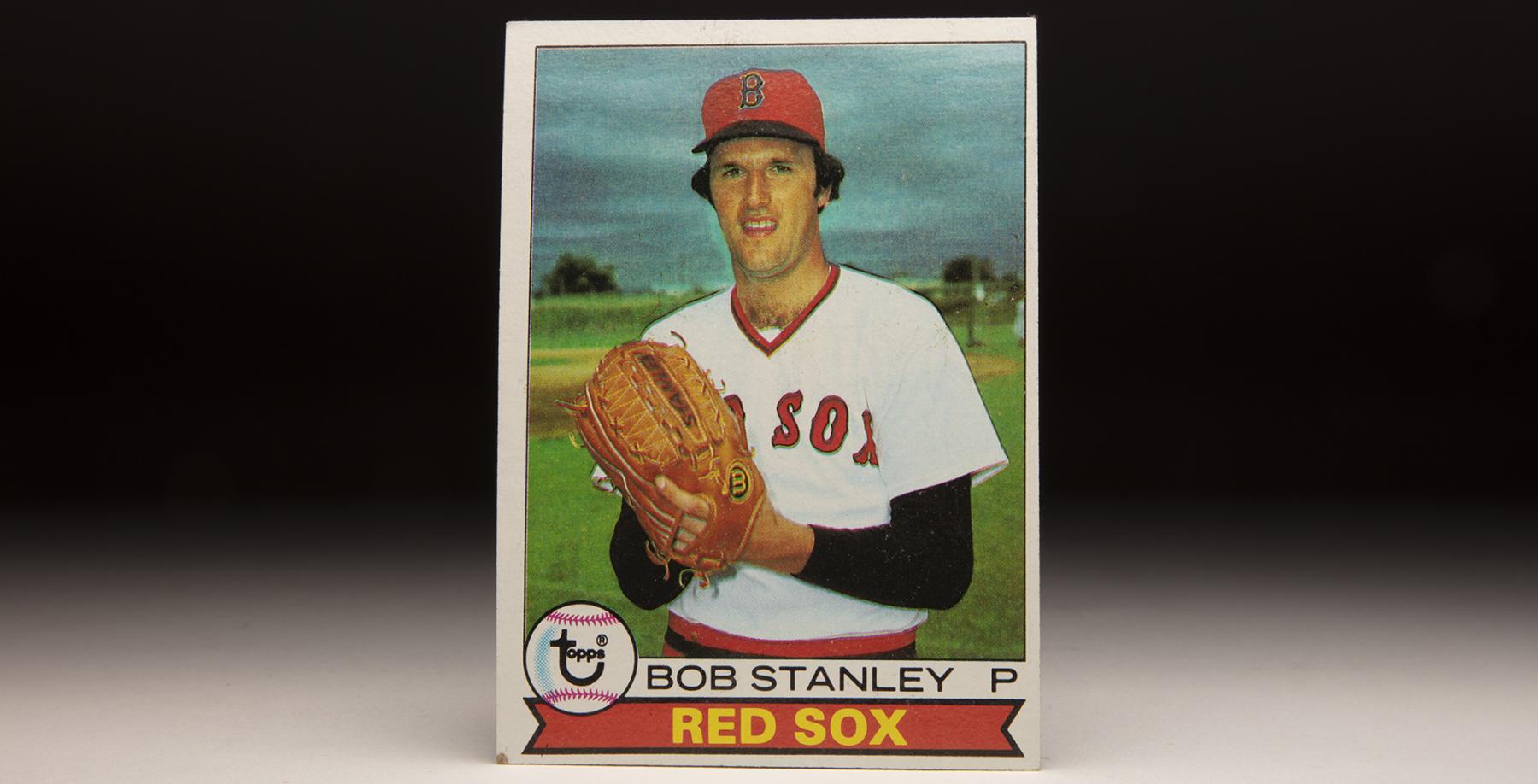

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bob Stanley

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bob Stanley

He delivered two of the most famous pitches in World Series history, and he will be forever remembered for being on the mound when the Mets rallied past the Red Sox in Game 6 of the 1986 Fall Classic.

But Bob Stanley also stands at the top of the Red Sox all-time games pitched list and once held the single-season and career team records for saves. Over his 13 years in the big leagues, few pitchers were more durable or versatile than the winningest pitcher ever to be born in the state of Maine.

Robert William Stanley was born Nov. 14, 1954, in Portland. His family moved to New Jersey when Stanley was 2 but the Maine connections – via family – remained strong.

“My uncle is still a Maine lobsterman,” Stanley told the Boston Globe in 1977.

Growing up in the Newark suburb of Kearny, N.J., Stanley often credited his pro pitching career to repeating second grade. Graduating high school a year later than his initial class, Stanley had the opportunity to switch from the infield to the mound when a crop of talented pitchers a year ahead of him finished school.

Stanley impressed scouts as a senior with his sinking fastball, and the Dodgers took Stanley in the ninth round of the 1973 June Draft. But Stanley turned down their offer of a $9,000 signing bonus and enrolled at Newark State College (now Kean University). Eligible for the January 1974 MLB Draft after leaving college, Stanley was selected by the Red Sox in the first round and agreed to a contract with Boston.

“The night the Dodgers sent one of their scouts around with a contract, I pitched a no-hitter,” Stanley told the Christian Science Publishing Society. “But with the kind of money the Dodgers offered, you’d have thought I was knocked out of the box. There was just no way we were going to reach an agreement.”

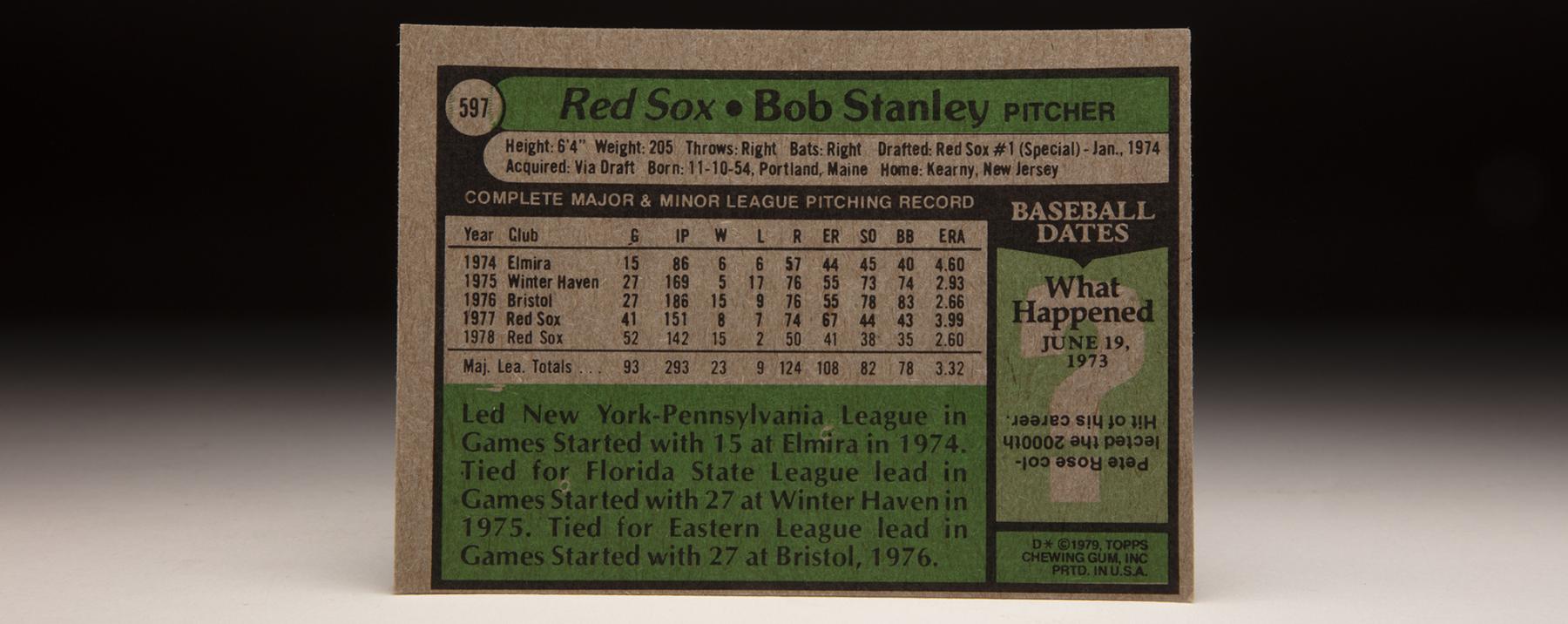

Stanley made his pro debut with Elmira of the New York-Penn League in 1974, going 6-6 with a 4.60 ERA over 86 innings in that short-season loop. In 1975, Stanley was promoted to Winter Haven of the Class A Florida State League, where he went 5-17 but posted a 2.93 ERA for a team that scored just 400 runs over 127 games.

“Winter Haven got me one run in my first eight starts, so most of the time I felt I was out there on my own,” Stanley said. “We were just a bad ballclub that was 30 games out of first place most of the time. I learned a lot about pitching that year.”

The Red Sox, however, overlooked Stanley’s record and sent him to Double-A Bristol of the Eastern League in 1976. There, Stanley was 15-9 with a 2.66 ERA over 27 starts – earning an invitation to Red Sox Spring Training in 1977.

Boston manager Don Zimmer, who had taken over midway through the 1976 campaign, was so impressed with Stanley that he made room for him in his Opening Day bullpen.

“I had good reports on Stanley before we ever decided to take him to Spring Training,” Zimmer told the Christian Science Publishing Society. “But that’s nothing new. Kids who throw exceptionally hard always get talked about. Only this kid was different. He really did throw bullets and his maturity – well, he acted like he’s been pitching for 20 years.”

Zimmer compared Stanley to his former teammate Don Drysdale, and others saw the resemblance as well.

“Stanley reminds me of a young Don Drysdale,” teammate Fergie Jenkins told the Globe in the spring of 1977. “But not as mean.”

Drysdale agreed – and saw a bright future for Stanley.

“Basically, Stanley is about as close to me as any young pitcher I’ve seen,” Drysdale, who was broadcasting games for the California Angels, said in 1977. “If I had anything to do with the Red Sox, I might think a hundred times before I’d change this kid. I got away with throwing a sinking fastball for more than 10 years in the big leagues and I wouldn’t be surprised if Stanley could too.”

Stanley made his big league debut in the fifth game of the 1977 season, allowing one earned run over four innings in relief of Luis Tiant and picking up the save as Boston beat Cleveland 8-4. Stanley notched his first win three days later on April 19, starting and working eight innings in an 11-3 win over Detroit. All six of Stanley’s appearances in May came as a starter – including a shutout win over the Angels on May 7 – but most of his games the rest of the year were out of the bullpen. Stanley finished the season with a record of 8-7 and three saves, working to a 3.99 ERA over 151 innings.

But those numbers did not guarantee Stanley a job in 1978, and – with minor league options remaining – the decision on his fate went down to the wire. Ultimately, Zimmer liked what he saw from Stanley’s final few outings during the exhibition slate and kept Stanley on the roster.

“He still needs to work on a slider,” Zimmer told the Associated Press, “and when he perfects that he’s going to be one helluva pitcher. I feel he can pitch any way I want to use him: Starting, long relief or short relief.”

By the end of April, Zimmer was using Stanley as his closer. He tallied three wins and three saves in May and five more saves in June. Then in August, Stanley recorded six wins despite only starting one game. He notched his 10th save of the season Sept. 27, then started on Sept. 29 on one day of rest against the Blue Jays – allowing just two hits over seven shutout innings in Boston’s 11-0 win. The victory improved Stanley’s record to 15-2.

Two days later, the Red Sox pulled into a tie for first place with the Yankees by beating Toronto 5-0 while New York fell to Cleveland 9-2 – setting up a winner-take-all game for the AL East title on Oct. 2 at Fenway Park. Stanley entered that game in the seventh inning after Mike Torrez gave up a three-run homer to Bucky Dent and walked Mickey Rivers. Thurman Munson then doubled off Stanley to score Rivers and give New York a 4-2 lead.

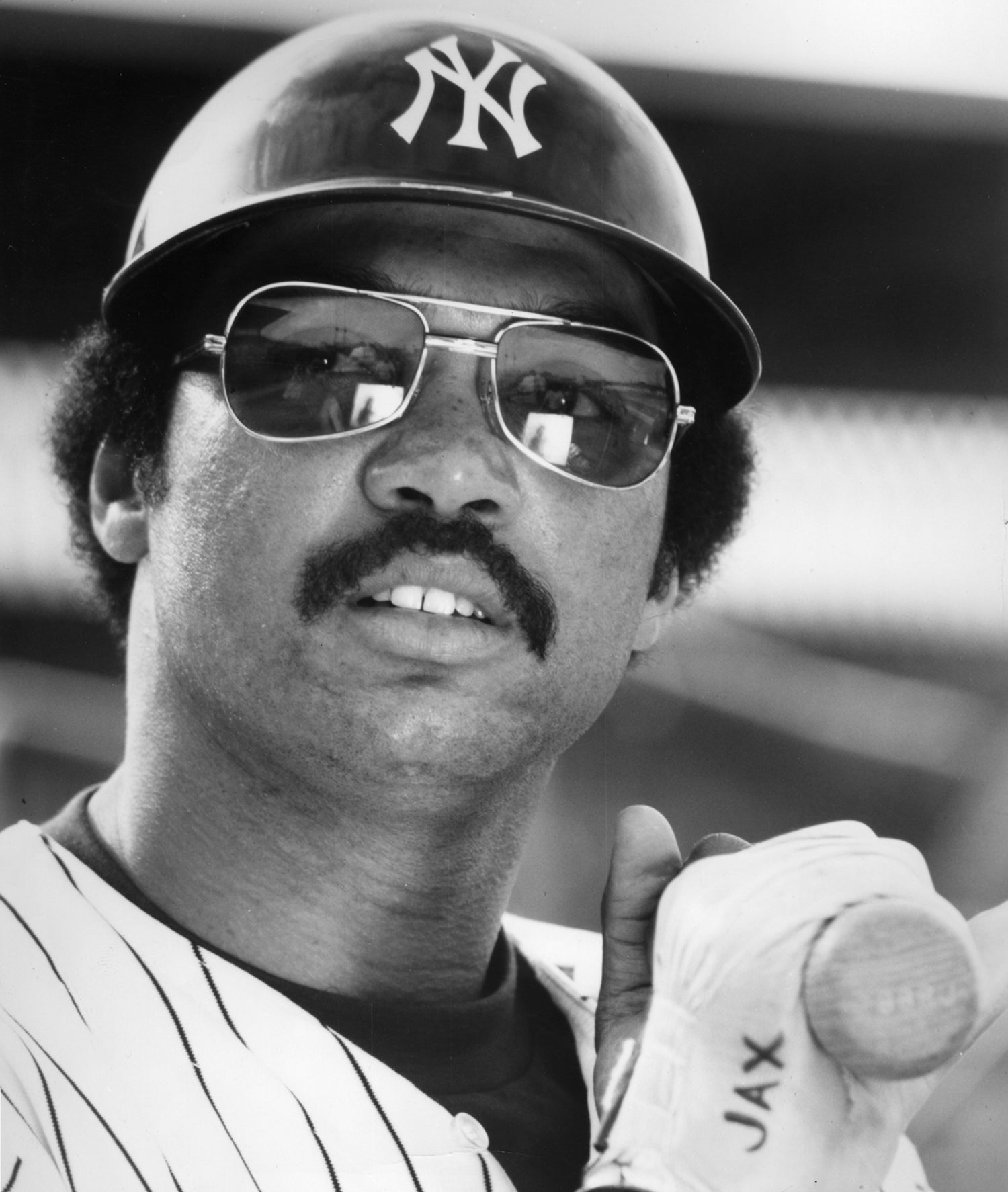

When Reggie Jackson led off the eighth with a homer off Stanley, Zimmer brought on Andy Hassler in relief. The Yankees would win the game 5-4.

“I knew it was out as soon as I hit it,” Jackson told the Associated Press about the home run.

The Yankees, who rallied from a double-digit games-back deficit during the season, went on to win the World Series.

Stanley, meanwhile, signed a three-year deal worth a reported $225,000 in February of 1979 and was penciled into the Red Sox’s rotation behind Dennis Eckersley and Torrez after finishing seventh in the 1978 AL Cy Young Award voting and 25th in the Most Valuable Player Award race. He threw two complete games in April, including a six-hit shutout of Seattle on April 26, and stayed in the rotation almost the entire year – finishing with a 16-12 record and 3.99 ERA over 40 appearances, including 30 starts. His 216.2 innings would be a career-high, and Stanley was named to the All-Star Game that summer – allowing one run over two innings in relief of starter Nolan Ryan.

But Zimmer preferred to use Stanley in a swingman role, and in 1980 the manager deployed his versatile right-hander 52 times, starting 17 games while going 10-8 with 14 saves over 175 innings.

“If I’m back as a manager (in 1981), there’s no question in my mind which way I’m going (with Stanley),” Zimmer told the Boston Globe late in 1980 season. “Stanley stays in the bullpen. Or if he doesn’t work for a stretch of a few days, he can spot start. But the guy’s great in the bullpen.”

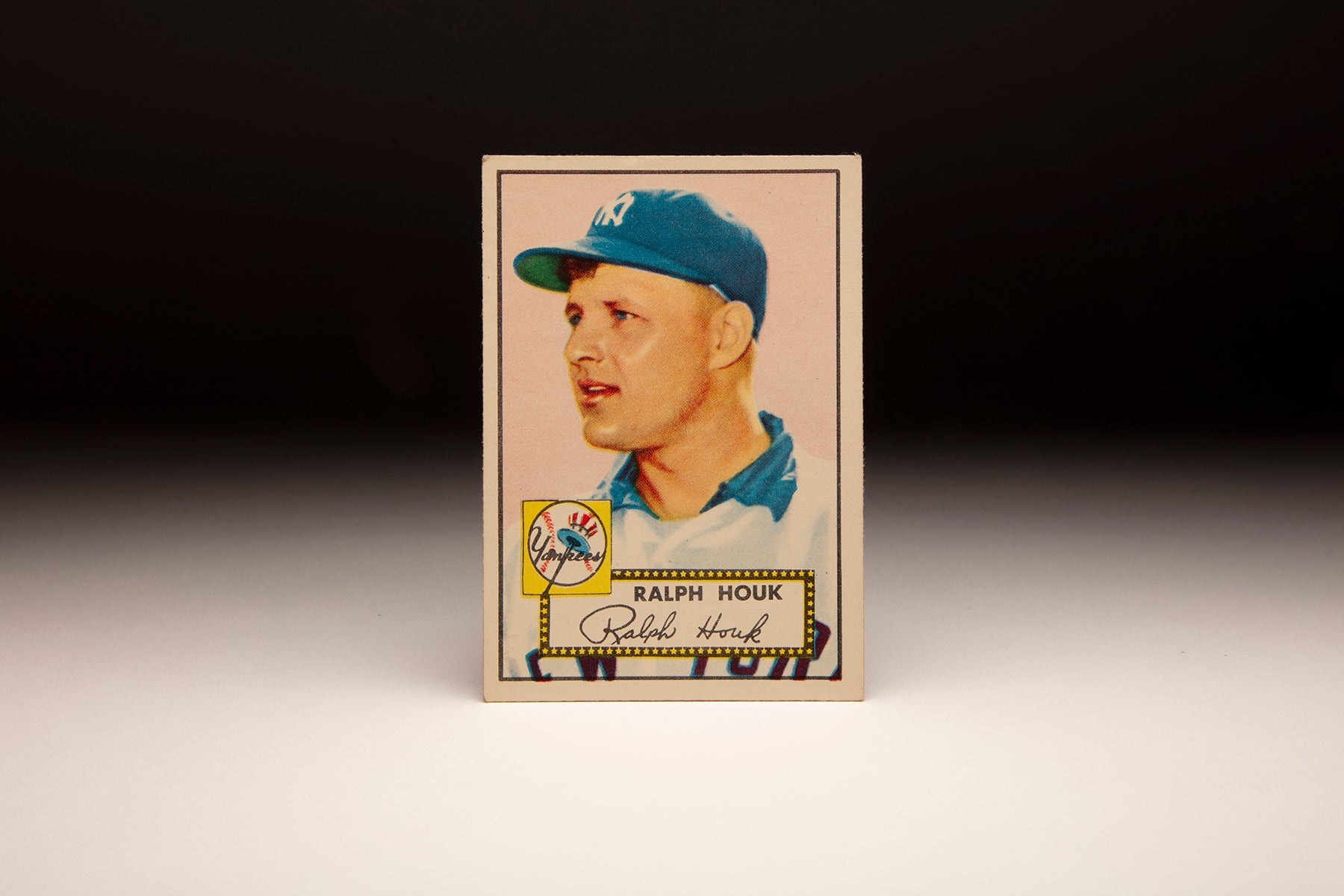

But Zimmer didn’t get the chance to use Stanley in 1981 because he was replaced late in the 1980 season. New manager Ralph Houk employed Stanley in long relief in 1981, and Stanley went 10-8 with a 3.83 ERA in 35 games. He started only once in that strike-shortened season but still tied Torrez for the team lead in victories.

“I like it out there,” Stanley told the Boston Globe of his time in the bullpen, “and realize the job I can do.”

Stanley also began tinkering with a spitball around this time, adding another option to his sinker/slider mix – or at least making hitters think the option was there.

“I really don’t need it because of my sinker,” Stanley told the AP. “But it does give me a psychological edge on the hitters.”

In 1982, Houk once again used Stanley in long relief – and the pitcher set a new AL record with 168.1 relief innings, appearing in 48 games with no games started for the first time in his career. Stanley was 12-7 with 14 saves and a 3.10 ERA – and matched his 1978 awards record by finishing seventh in the AL Cy Young vote and 25th in the MVP race. Boston won 14 of the 18 games in which he threw at least four innings.

“As far as I’m concerned, he’s one of the best all-around throwers I’ve ever managed,” Houk – who managed Hall of Famers Whitey Ford and Jack Morris among other stars – told the Tampa Tribune in the spring of 1983. “If we get ahead early in a ballgame and our starter is having trouble, Stanley is just like a fresh starter coming in there who can last four or five innings or more.”

Houk continued to use Stanley in a multiple-inning role in 1983 but generally limited Stanley’s outings to when the Red Sox had a lead. The result was a team-record 33 saves to go along with an 8-10 record (Stanley’s first losing mark of his career) and a 2.85 ERA over 145.1 innings. Stanley made 64 appearances but not one start and was named to his second All-Star Game.

Stanley continued in the closer’s role in 1984, saving 22 games while going 9-10 with a 3.54 ERA in 57 appearances. On Feb. 13, 1985, Stanley and the Red Sox agreed to a new four-year extension that would pay him a little more than $1 million a year.

“I never thought I would earn that kind of money throwing a baseball,” Stanley told the Daily Hampshire Gazette. “I am really lucky. If I weren’t playing baseball, I’d be out working in construction in this cold weather. Thank God for giving me a sinkerball.”

But in 1985, Stanley suffered the first major injury of his career when he missed all of September after having a growth on his right index finger removed. He pitched effectively in 48 games, going 6-6 with 10 saves and a 2.87 ERA.

Then in 1986, the Red Sox rode a 24-4 season by Roger Clemens all the way to the World Series. Stanley closed games for the first half of the season but was moved to a lower-leverage role late in the year by manager John McNamara, who turned to Calvin Schiraldi in short relief starting in August.

However, McNamara welcomed Stanley’s veteran presence in the ALCS vs. the Angels, and in the memorable Game 5 Stanley pitched 2.1 innings, allowing three runs but keeping the game close before the Red Sox rallied to win the game in the 11th and stave off elimination. Stanley pitched in Game 6 as well, allowing only one earned run while working the final two frames of Boston’s 10-4 victory.

The next day, the Red Sox won Game 7 to advance to the Fall Classic. Within days, Stanley would become a household name.

He saved Game 2 by working three scoreless innings in relief of Clemens and winner Steve Crawford, worked two more scoreless frames in Game 3 and another in Game 4. Then in Game 6, the Red Sox held a 5-3 lead going into the bottom of the 10th and needed just three outs for their first World Series title since 1918.

Schiraldi, in the game since the start of the bottom of the eighth, got the first two outs before allowing singles to Gary Carter, Kevin Mitchell and Ray Knight to make the score 5-4. McNamara then turned to Stanley to face Mookie Wilson.

With the count 2-and-2, Stanley needed one strike to give Boston its title. But Wilson fouled off two pitches at that point – and Stanley’s seventh pitch of the at-bat sailed past catcher Rich Gedman for wild pitch, allowing Mitchell to score from third to tie the game.

Wilson fouled off two straight 3-and-2 offerings before hitting one of the most famous grounders in history – a slow roller that went through Bill Buckner’s legs at first base, bringing home Knight to win the game.

Two days later – after rain wiped out the first attempt at Game 7 – Stanley got the final out of the seventh inning, a frame that saw the Mets score three times to take a 6-3 lead. He would be relieved by Al Nipper to start the eighth, after Boston rallied to cut New York’s lead to 6-5. Nipper would allow two runs in a game the Mets would ultimately win 8-5.

“I’ve watched the films a lot – until I get sick,” Stanley would say that winter about Game 6. “It just wasn’t meant to be. There’s nothing that will change things. Baseball’s not like golf – there’s no mulligan.”

In 1987, the Red Sox moved Stanley back into the rotation – and he started on Opening Day, taking the loss in a 5-1 defeat to Milwaukee.

“It will be like starting over again,” Stanley told the AP of his move into the rotation.

But by May, Stanley was 3-8 with a 4.92 ERA when he was returned to the bullpen. He finished the season with a 4-15 record and 5.01 ERA, drawing regular choruses of boos from the Fenway Park faithful.

The Red Sox moved Stanley back to the bullpen in 1988, and he helped Boston win another AL East title by going 6-4 with five saves and a 3.19 ERA in 57 games while serving as a set-up man for newly acquired closer Lee Smith. Stanley appeared in two games in the Athletics’ sweep of the Red Sox in the ALCS, allowing one run over one inning of work.

In 1989, however, Stanley criticized manager Joe Morgan’s handling of the team and appeared in just 43 games, going 5-2 with four saves and a 4.88 ERA. With his contract expiring, Stanley announced on Sept. 25 that he would retire at the end of the season.

“I’m going home to my kids,” Stanley told the AP. “I won’t even think of trying to come back. The time has come.”

Stanley retired as the Red Sox’s all-time leader in games pitched (637) and saves (132) while posting a 115-97 record and 3.64 ERA. Since the save became an official statistic in 1969, Stanley is one of only two pitchers – along with Hall of Famer John Smoltz – to have at least 100 wins, 100 saves and a winning percentage of at least .540.

For a pitcher that relied mostly on one pitch, it was a career that exceeded all expectations.

“I didn’t have the amount of pitches needed to be a starter,” Stanley told the Tampa Tribune in the spring of 1983. “You have to trick people a lot and throw harder than I do.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

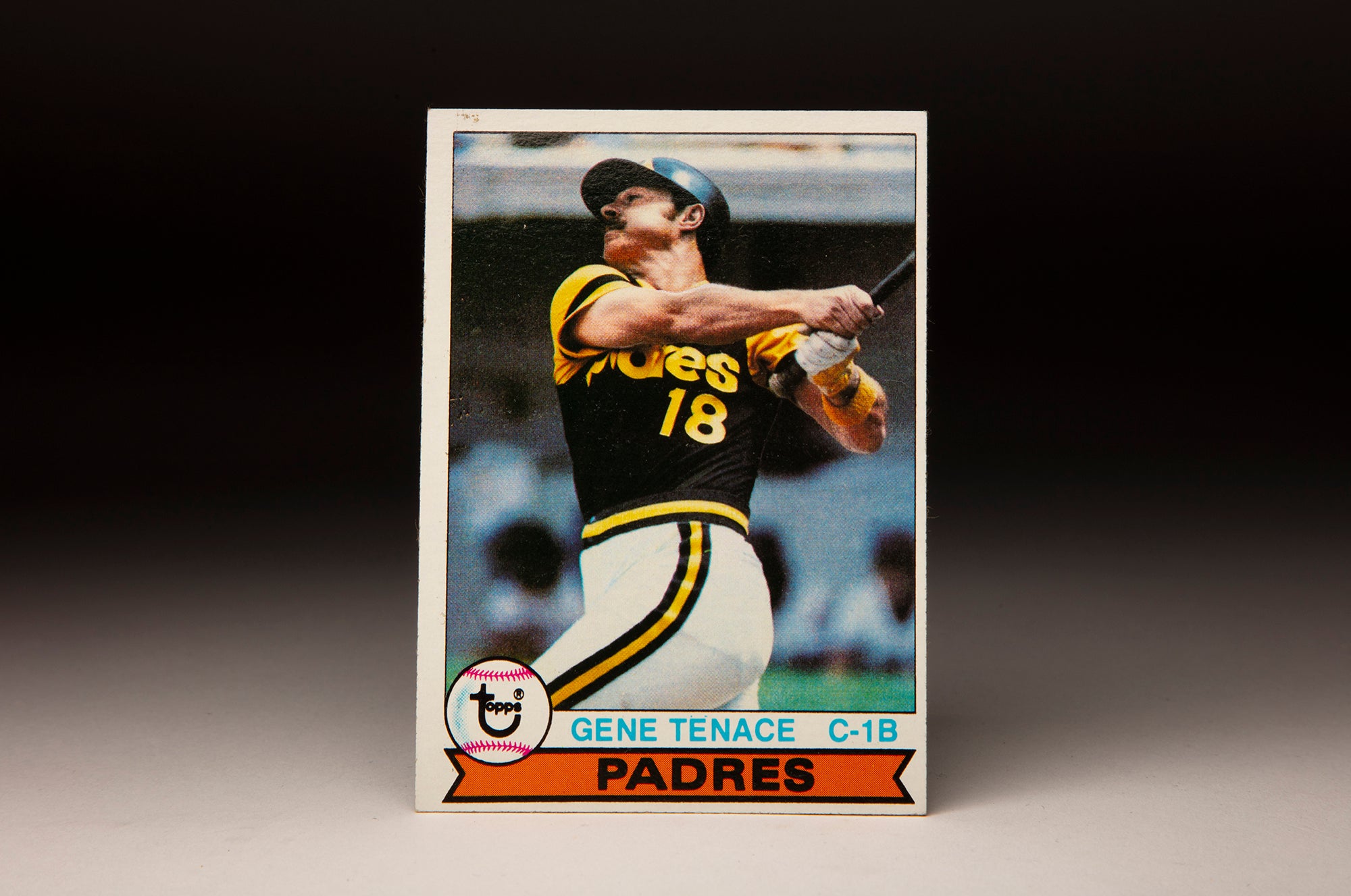

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Gene Tenace

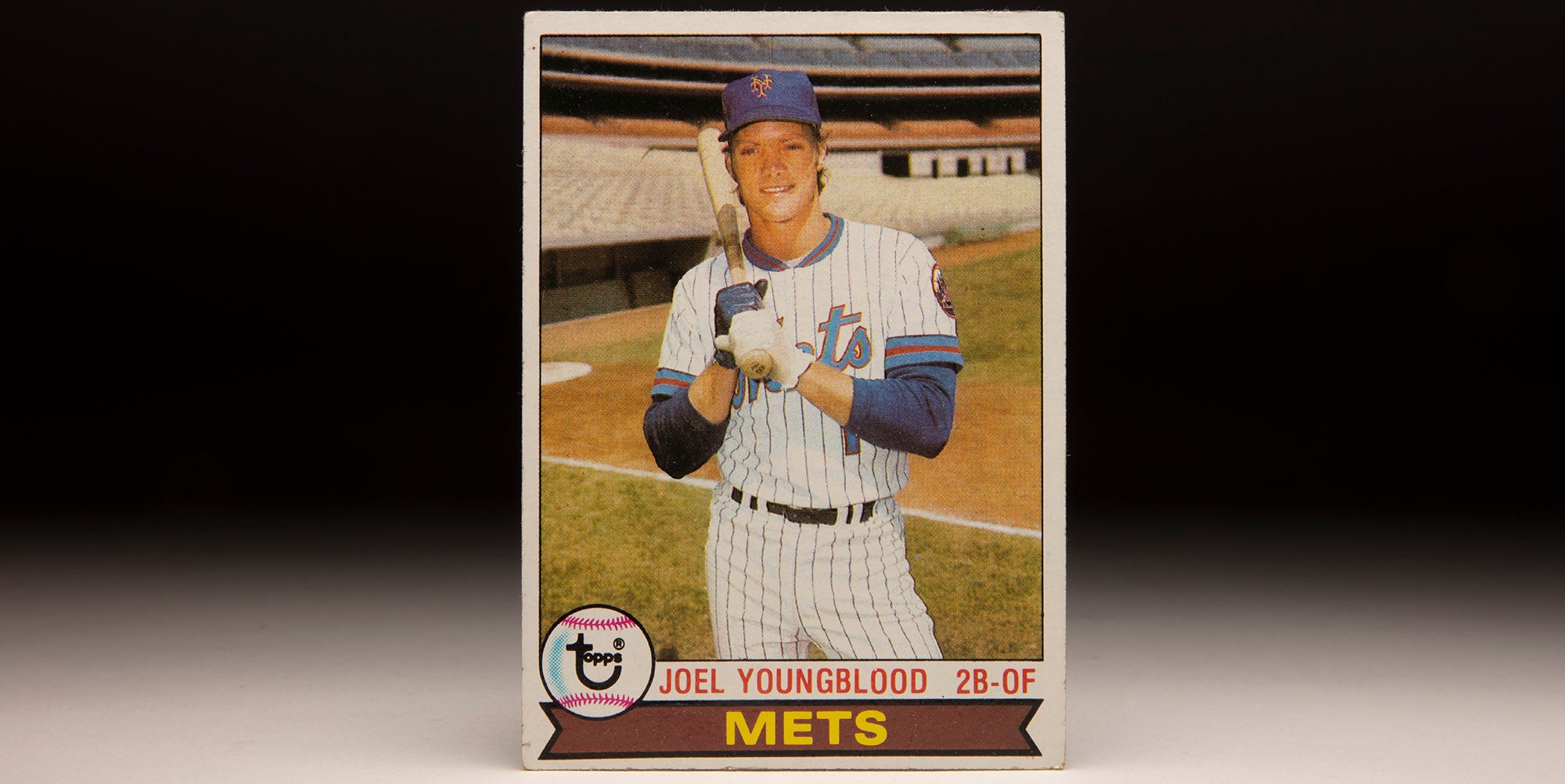

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Joel Youngblood

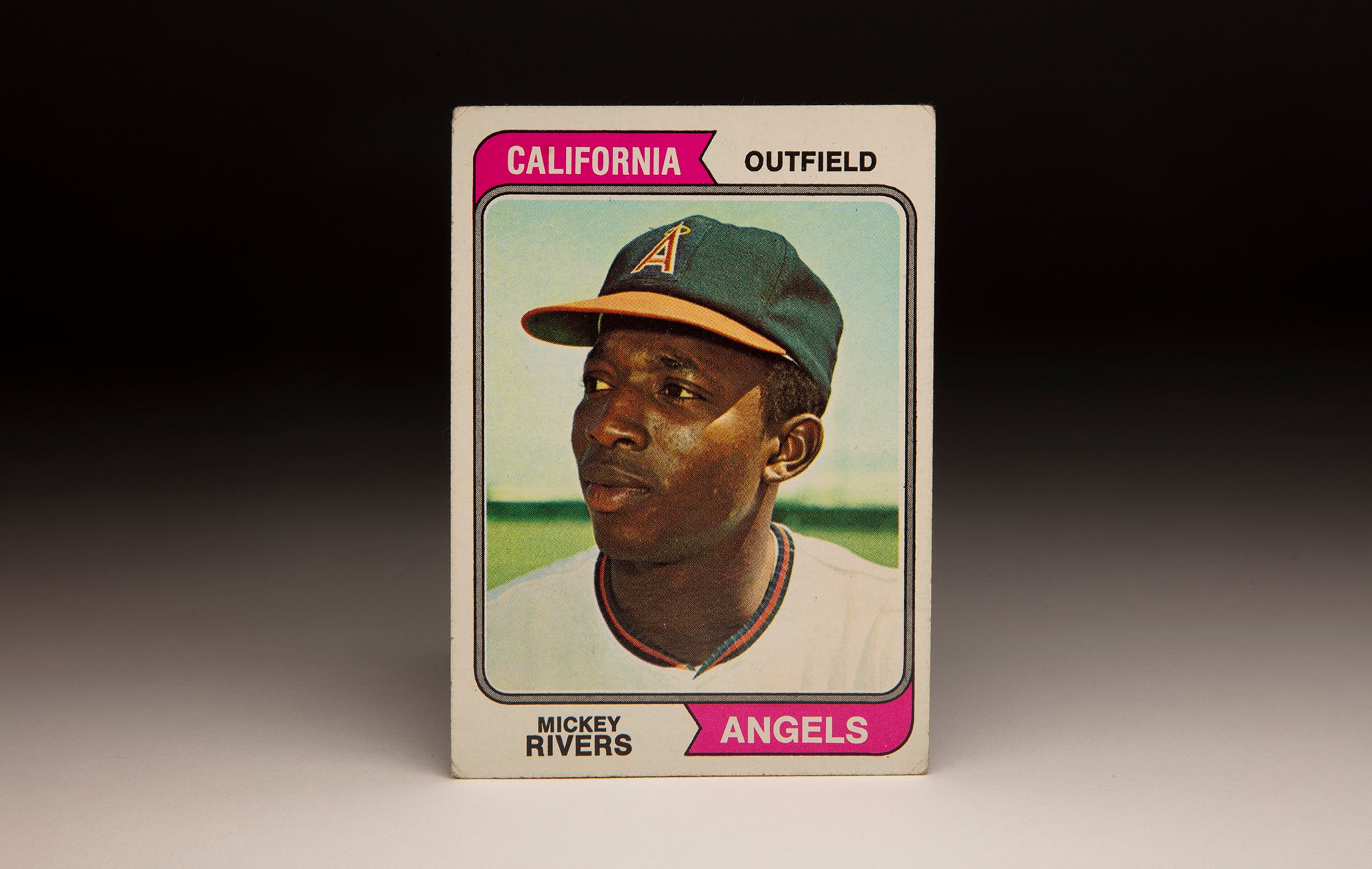

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Mickey Rivers

#CardCorner: 1952 Topps Ralph Houk