- Home

- Our Stories

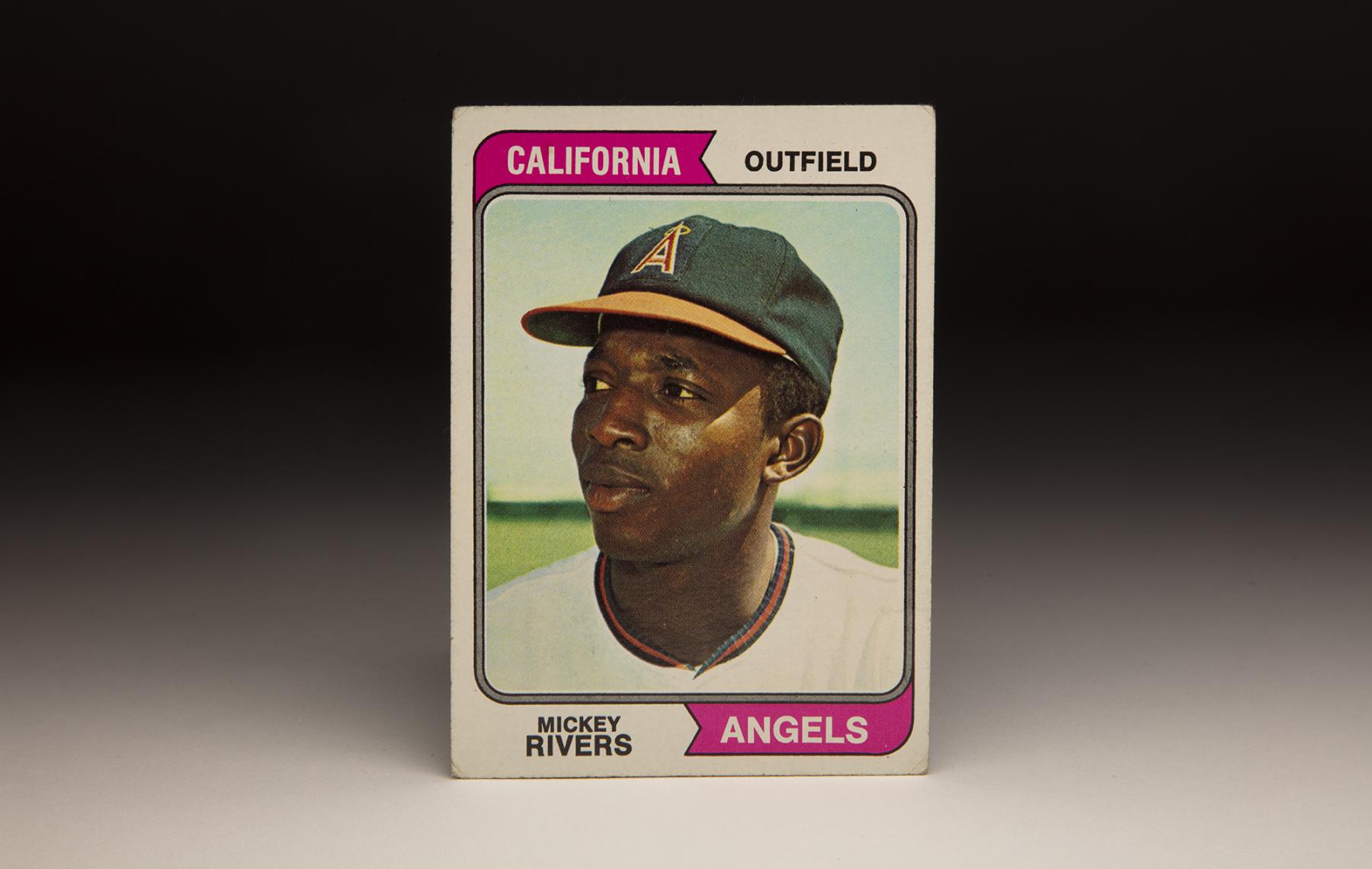

- #CardCorner: 1974 Topps Mickey Rivers

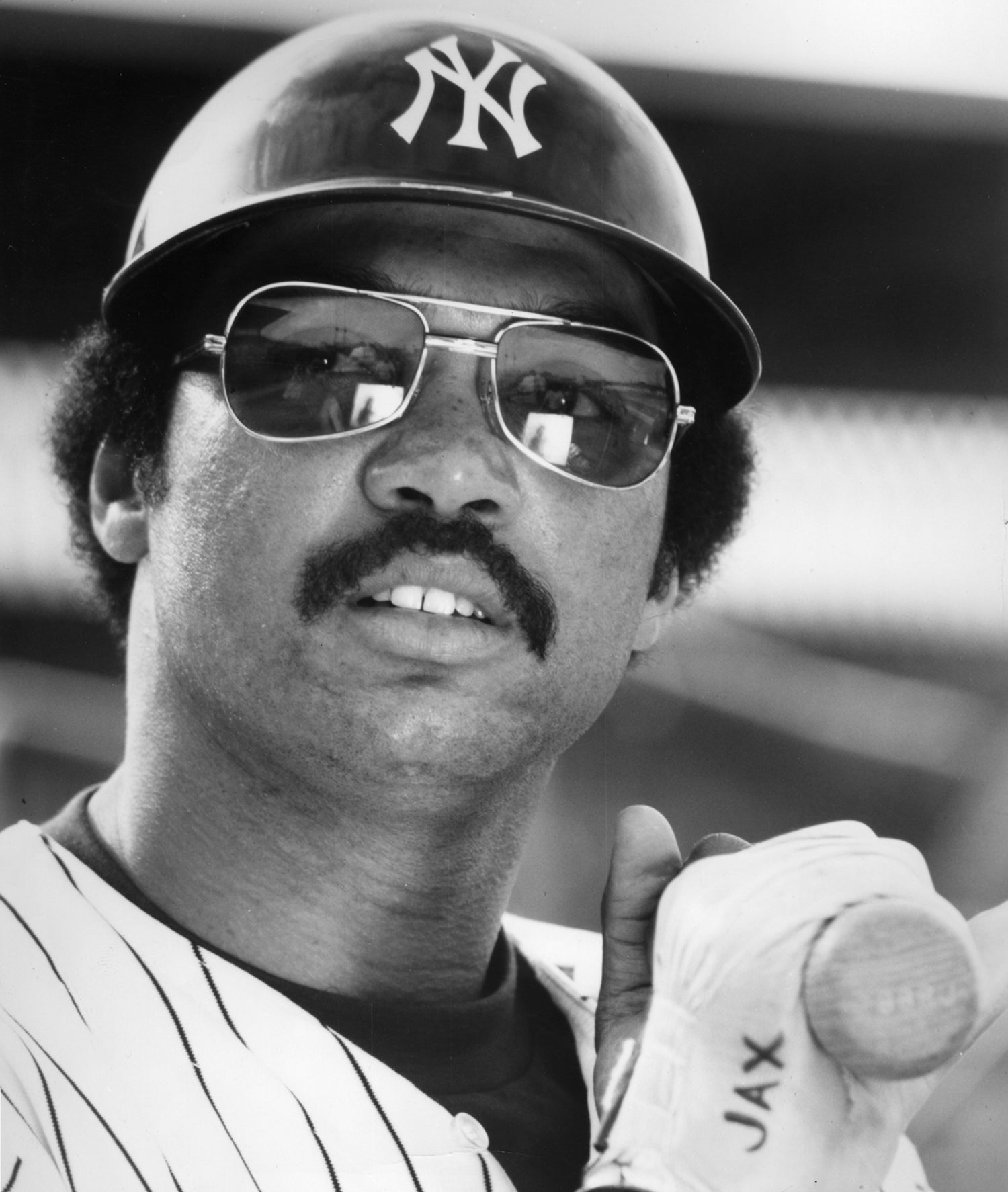

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Mickey Rivers

Mickey Rivers was on top of the baseball world by the end of the 1978 season as the center fielder of the back-to-back World Series champion Yankees and a quotable, easy-going source for the media.

Ten years earlier, all that would have seemed impossible for a man who grew up in tough surroundings in South Florida.

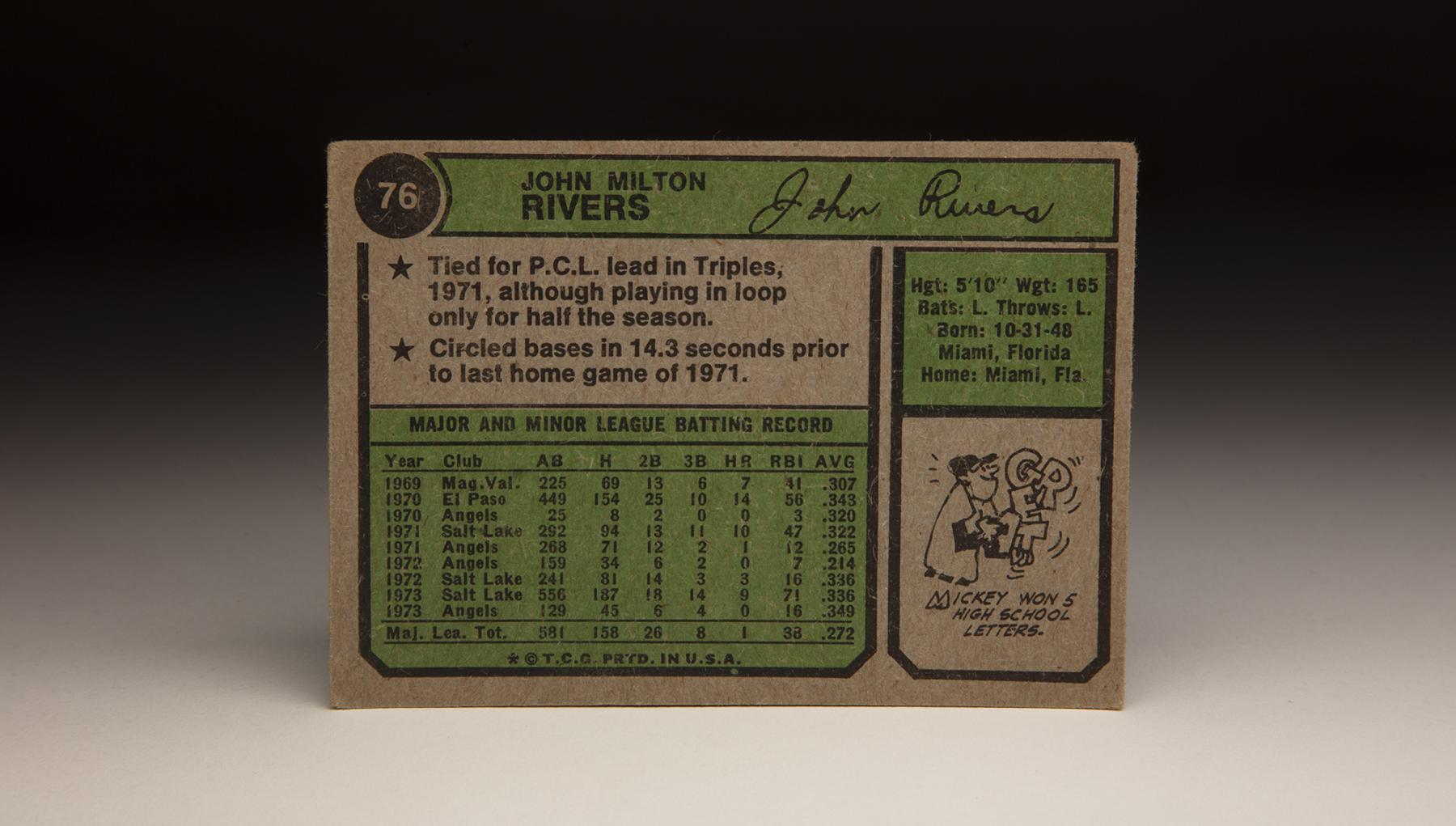

John Milton Rivers was born Oct. 30, 1948, in Miami. He moved in with his grandmother, Flora Fambro, before he turned 10.

“My father wouldn’t let me play ball,” Rivers told the Miami News in 1977. “My grandmother would.”

Baseball, however, couldn’t shield Rivers from his surroundings.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

“I used to get in some fights when I was growing up… serious fights,” said Rivers, who came of age in Miami’s Brownsville neighborhood. “It was rough. In the parks, a couple of guys used to carry around guns. Those are the guys I’d play baseball with.

“There was nothing on the streets but trouble.”

But with his grandmother’s encouragement, Rivers – using his natural speed and spurred on by a desire to excel – honed his skills in youth leagues and at Miami’s Northwestern High School, where he earned two letters in baseball and also played basketball, football and track. He found his way onto the baseball team at Miami-Dade Junior College-North, where coach Demie Mainieri took him under his wing.

“He used to hit off his front foot and he didn’t throw well from the outfield,” Mainieri told the Miami News. “But he could run like hell.”

Rivers’ adjustment to college life was not without challenges, but his speed quickly put him on the radar of big league scouts. He was selected in the first round by the White Sox in the January 1968 MLB Draft prior to his junior season, but returned to school before being taken in the eighth round by the Mets in the secondary phase of the June 1968 draft. Returning to school once again, Rivers was taken No. 8 overall in the secondary phase of the January 1969 draft by the Senators – and again went back to school.

Finally, in June of 1969, the Braves took Rivers in the second round of the secondary phase of that draft after he hit .365 with 27 steals that season. Rivers reported to the Magic Valley Cowboys of Twin Falls, Idaho, that summer, and hit .307 with 31 steals and a .464 on-base percentage against Pioneer League pitching.

Just after the season ended, however, the Braves sent Rivers and Clint Compton to the Angels for Hoyt Wilhelm and Bob Priddy. The Angels then assigned Rivers to Double-A El Paso, where he hit a Texas League-best .343 in 1970 with 99 runs scored and 30 steals in 114 games. It was in El Paso that Johnny Rivers became Mickey Rivers – thanks to his Sun Kings teammates, who bestowed the nickname on him.

On Aug. 3, the Angels brought Rivers to California for a stint while outfielder Alex Johnson – who would go on to win the AL batting crown that year – served his summer commitment in the National Guard. Rivers made his big league debut on Aug. 4 as a pinch-hitter, appeared in three games before returning to El Paso to finish the minor league season and then returned as a September call-up.

“Frankly, he’s our best young outfielder,” Angels general manager Dick Walsh told the Miami Herald. “In two years, Mickey should be playing in Anaheim.”

Rivers spent most of that offseason with his National Guard unit, then was assigned to Triple-A Salt Lake City to start the 1971 campaign. After hitting .322 with 54 runs scored and 47 RBI in 72 games, Rivers was recalled to the Angels at the end of June – just days after Johnson was suspended for “failure to give his best” in one of the most hotly-covered stories of the season. He played nearly every day for the Angels for the rest of the season, hitting .265 with 13 steals in 79 games. He then hit .349 in the Dominican League that winter.

Angels management believed that 1972 would be Rivers’ breakout season.

“Mickey Rivers is going to be one of the most exciting players in the American League,” new Angels general manager Harry Dalton told the Press-Telegram in Long Beach, Calif. “There’s no telling how good he’s going to get.”

But after earning the job as California’s starting center fielder, Rivers found himself in a nagging slump. His batting average hovered around the .220 mark for most of the spring before the Angels sent him back to Salt Lake City for the rest of the summer. Rivers hit .336 in 59 games in Triple-A before being recalled in September, finishing the year with a .214 batting average in 58 games for California.

“One day he can remind you of a superstar,” said Angels manager Del Rice, who skippered Rivers multiple times throughout the minors. “And the next he makes easy plays look difficult. But he has a flair for the game.”

Rivers was sent to Triple-A again to start the 1973 season, and he hit .336 with a Pacific Coast League-best 47 steals and 113 runs scored for Salt Lake City. He was again recalled in September, and this time Rivers hit .349 with eight steals in 30 games.

“I fully expect to be here next year,” Rivers told The Independent of Long Beach, Calif., “doing something for the club.”

For the second time in three seasons, Rivers won the starting center field job in Spring Training. But in 1974, Rivers hit consistently from Day 1, finishing at .285 with 30 steals and an AL-best 11 triples in 118 games before a broken right hand sidelined him for the rest of the season starting in late August.

Dick Williams had taken over the Angels during the 1974 campaign, and in 1975 Williams decided to let his young Angels – who lacked veteran power hitters – run wild on the base paths.

“When it comes to stolen bases,” Williams quoted Rivers as saying in his 1990 biography “No More Mr. Nice Guy”, “this year I’m going to double my limit.”

Rivers was as good as his word, leading the AL with 70 steals in 1975 and again pacing the league in triples, this time with 13. He appeared in a career-high 155 games and hit.284, solidifying himself as one of the best young hitters in the game.

Following the season, however, the Angels parted with Rivers – sending him and pitcher Ed Figueroa to the Yankees in exchange for Bobby Bonds. It was a trade meant to inject power into the California lineup. Instead, it added two important pieces to a Yankees team set for a championship run.

“My favorite players (as a youngster) were Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris,” Rivers told the Miami Herald on the day of the trade. “I’ve always wanted to be up there someday and try to do better than those guys.”

Rivers quickly entrenched himself as the Yankees center fielder. And though he lacked the pure power that Mantle demonstrated at the position, Rivers proved to be the spark the Yankees lacked. He hit .312 in 1976 with 95 runs scored, 67 RBI and 43 steals, helping New York win its first pennant since 1964. But after hitting .348 in the ALCS to help the Yankees defeat Kansas City, Rivers – and the rest of the team – struggled to hit against the Reds in the World Series, where Cincinnati swept New York.

Coming off a season where he was named to his first All-Star Game and where he finished third in the American League Most Valuable Player voting, Rivers signed a three-year contract worth $400,000.

“Rivers can do just about anything,” said Mickey Mantle prior to the 1977 season.

The Yankees brought Reggie Jackson aboard after the 1976 season, setting the stage for a tumultuous year that would nearly tear the clubhouse apart. But Rivers continued to produce, hitting .326 with 79 runs, 12 homers, 69 RBI and 22 steals. The Yankees again defeated the Royals in the ALCS – with Rivers driving in the tying run in the top of the ninth of Game 5 and scoring the team’s fifth run in what became a 5-3 victory.

In the World Series, Rivers had six hits as the Yankees – behind Jackson’s five home runs – defeated the Dodgers in six games.

“Mickey Rivers is the offensive catalyst of our team,” Reggie Jackson told the Miami News in Spring Training of 1977. “You couldn’t pay him any higher compliment than that.”

Rivers’ production tailed off in 1978, another season that saw the Yankees battle among themselves as they chased the pennant. Rivers hit .265 with 25 steals and 78 runs – scoring the fourth run of the seventh inning, following Bucky Dent’s go-head three-run home run, of the Yankees’ 5-4 win over Boston in the one-game AL East tiebreaker on Oct. 2 at Fenway Park.

Rivers proceeded to hit .455 in the ALCS and .333 in the World Series as the Yankees repeated as champions.

The fragile forces that kept the Yankees together from 1976-78, however, was torn apart in 1979. Rivers was traded to the Texas Rangers on July 30 in an eight-player trade that was essentially Rivers for Oscar Gamble, though the deal took days to finalize because the Commissioner’s Office objected to “certain provisions of the deal.”

Three days after the trade was first announced, Yankees captain Thurman Munson perished in a plane crash.

Rivers finished the 1979 season with a .293 batting average, 72 runs scored and 50 RBI in 132 games for the Rangers and the Yankees. Reports of his missing team flights and leaving the team for other short spurts surfaced at the time of the trade.

“It goes a lot deeper than it shows,” the Associated Press quoted Yankees manager Billy Martin, who returned to the team in 1979 after being dismissed midway through the 1978 season. “I’m sorry to see (Rivers) go.”

Rivers battled financial problems throughout his Yankees days – including incurring debts from horse racing and dog racing – and brought them to Texas, but it never affected his game. In 1980, Rivers had his best season – hitting .333 (the best single-season average in franchise history to that point) with 210 hits, 96 runs scored, 32 doubles and 60 RBI – garnering MVP votes for the fourth time in five seasons.

“I’ve learned what I’ve got to do and what I can’t do,” Rivers told the Miami News. “I think the younger guys on the team know what kind of ballplayer I am. And I think they respect me.”

Rivers signed a three-year contract extension following the season worth a reported $370,000 per year. He was headed for a virtual repeat of his 1980 season in 1981 when the strike wiped out most of June and July. He finished with a .286 batting average and 62 runs scored in 99 games, but at 32 Rivers was beginning to show signs of wear.

In 1982, a knee injury limited him to just one game prior to mid-July, and he did not appear in the field in any of his 19 games that season – either DH’ing or pinch hitting every time.

Rivers recovered enough to hit .285 in 96 games in 1983 and then hit .300 in 102 games in 1984, serving as a DH in most of those games.

On April 4, 1985, the Rangers released Rivers – ending his big league career.

“Ain’t no sense in worrying about things you can’t control, because if you can’t control them it doesn’t do any good to worry,” Rivers said in a piece of advice attributed to him many times during his career. “And ain’t no sense in worrying about things you can control, because if you can you just control it and don’t worry about it.”

Rivers had one more stop in pro ball: Playing for Williams with the West Palm Beach Tropics of the short-lived Senior Professional Baseball Association 1989. Until leg injuries caught up with him, Rivers led the league in hitting.

Rivers retired with a .295 batting average over 15 big league seasons, with 1,660 hits, 267 stolen bases and two World Series rings.

“I don’t know where I’d be today if it wasn’t for my grandmother,” Rivers said in 1977. “I promised that I’d make it just for her. Without her pushing me, I just don’t know what would’ve happened to me.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

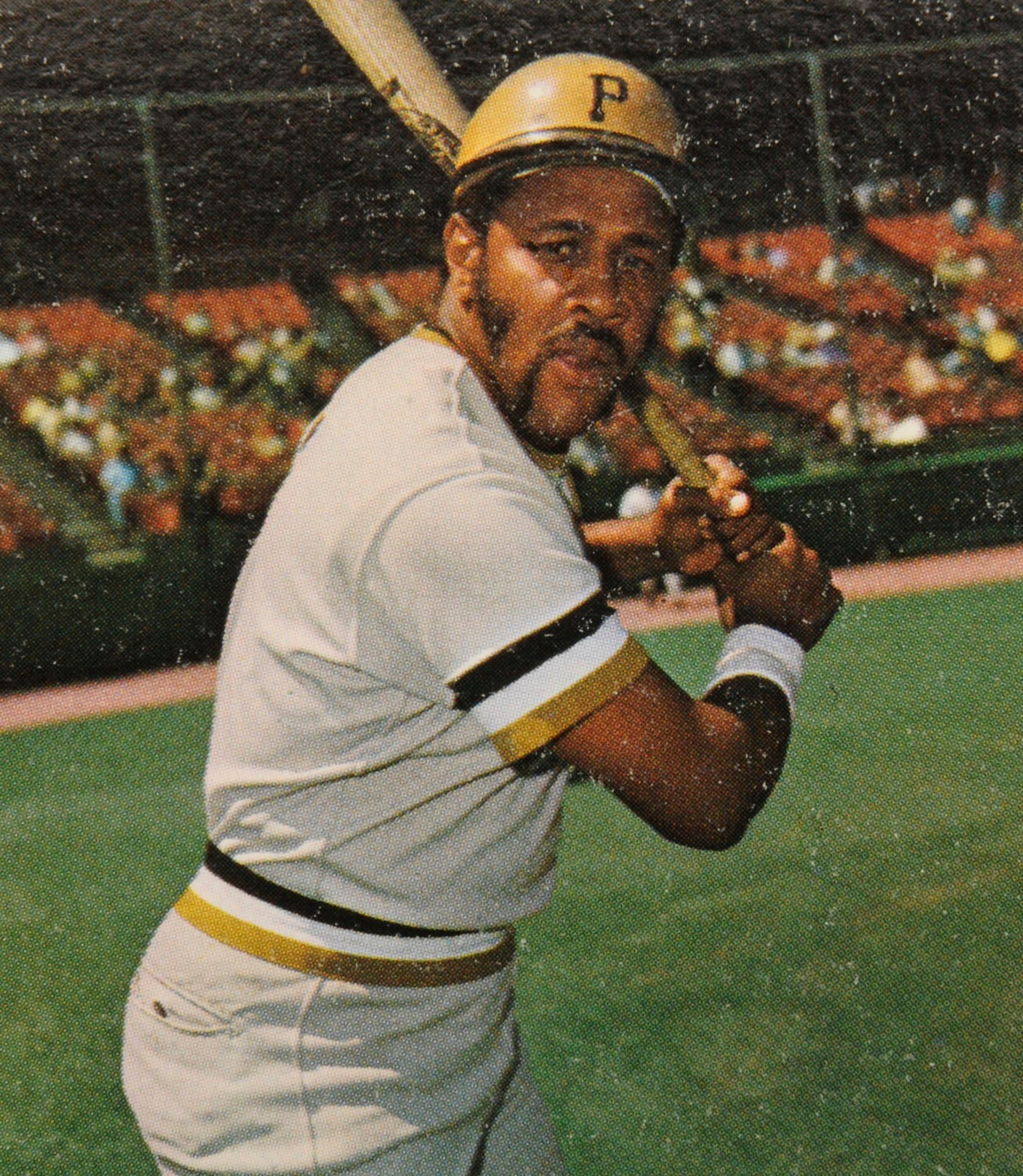

Related Stories

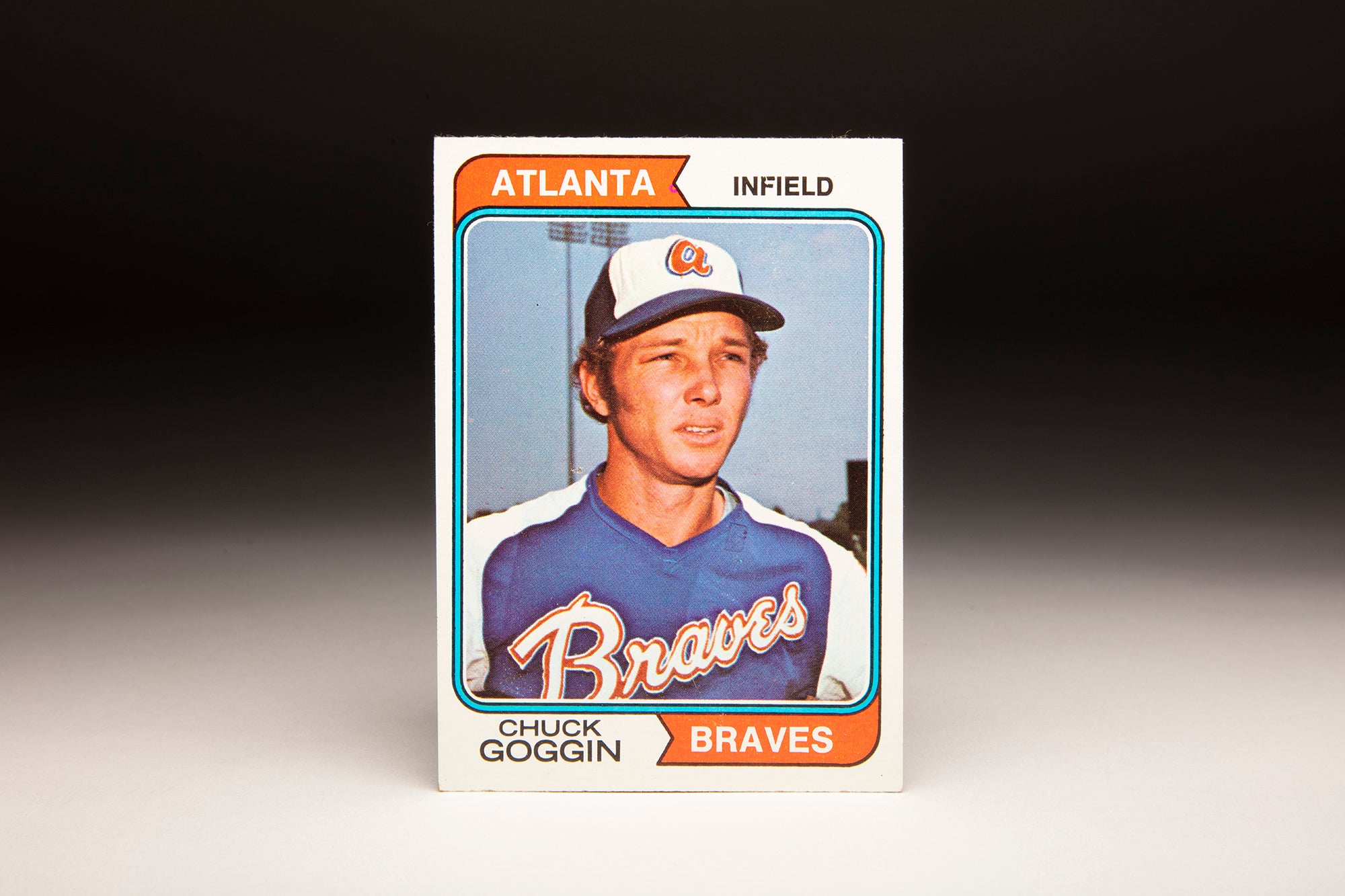

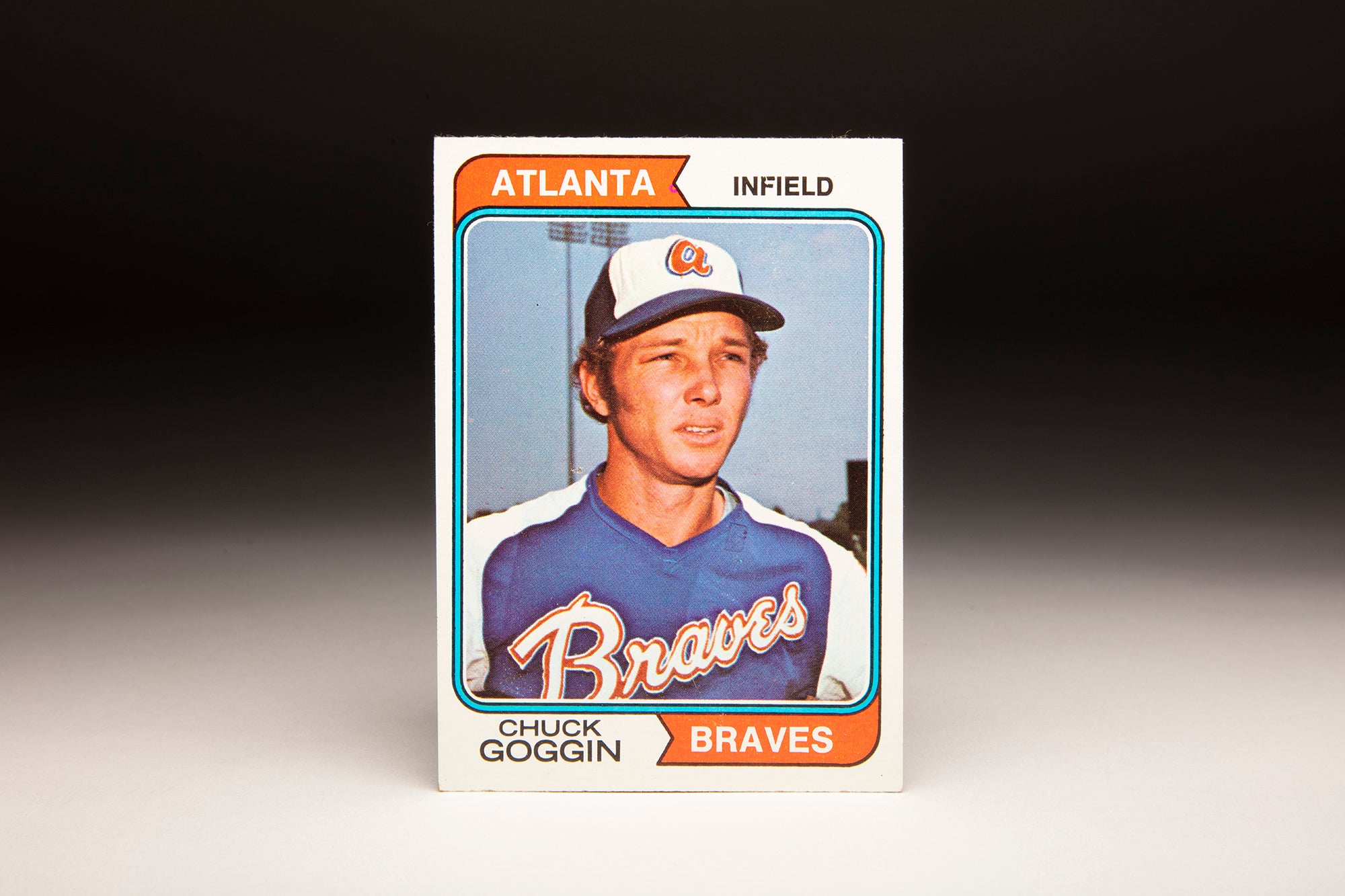

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Chuck Goggin

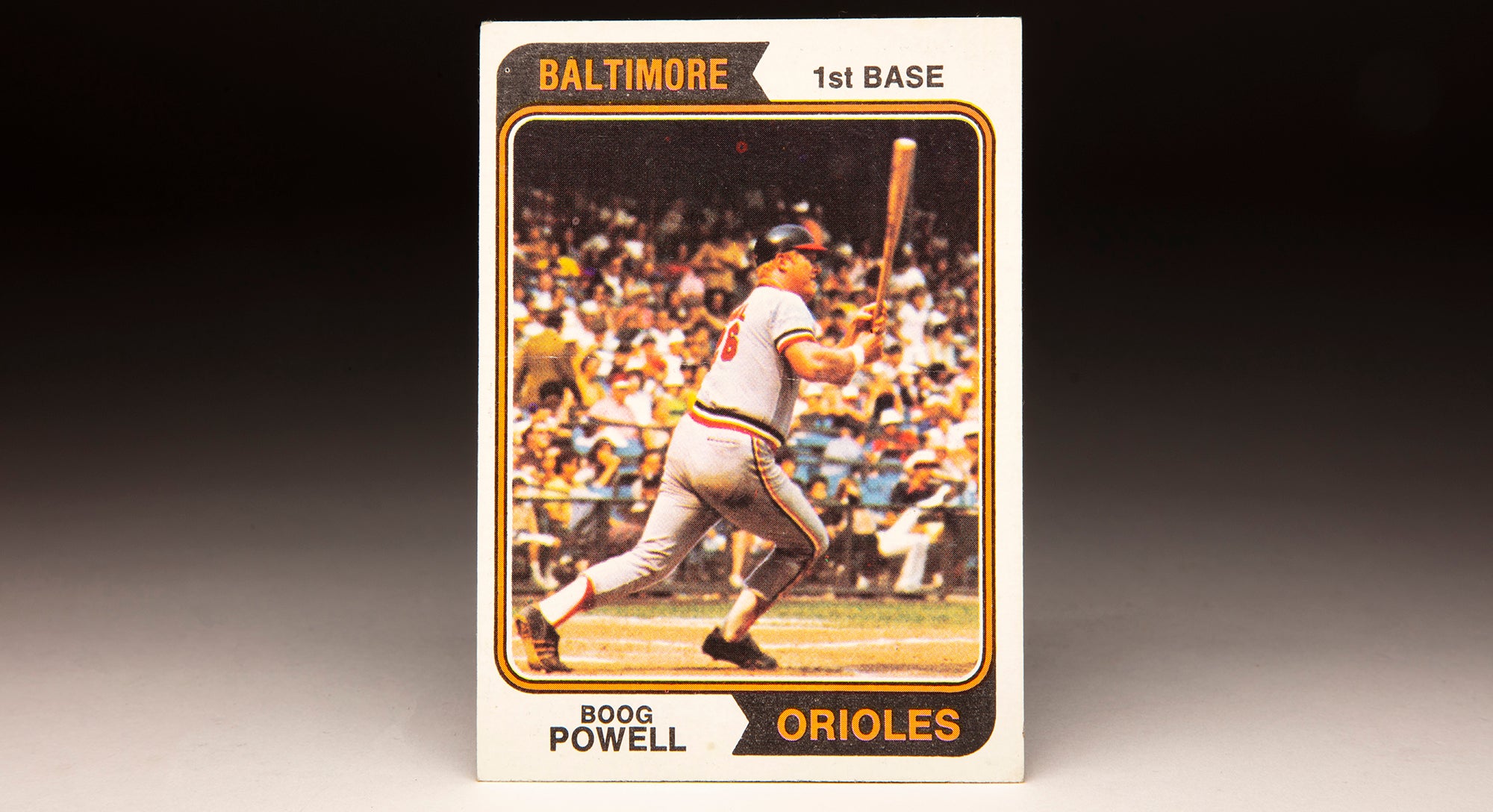

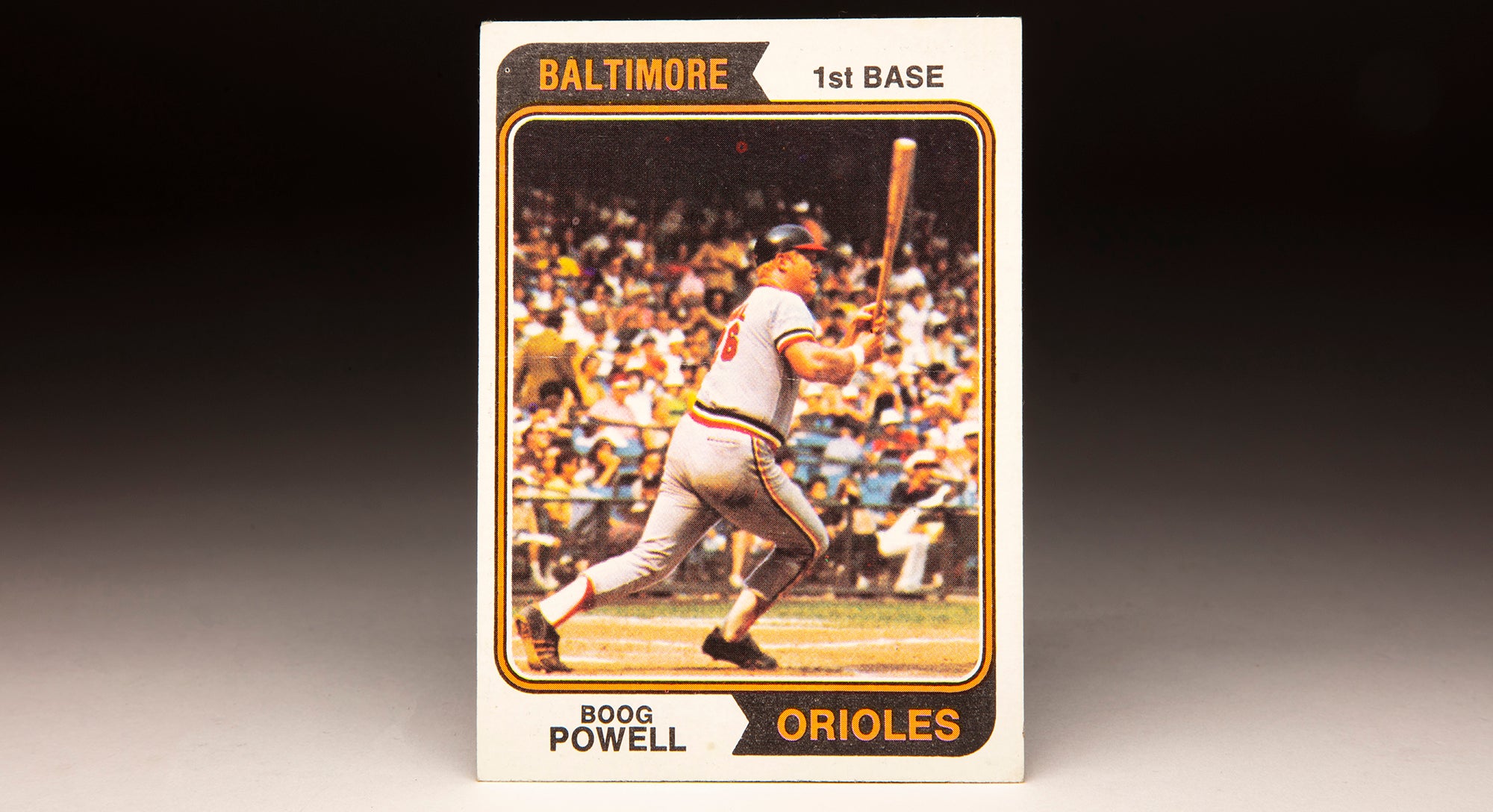

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Boog Powell

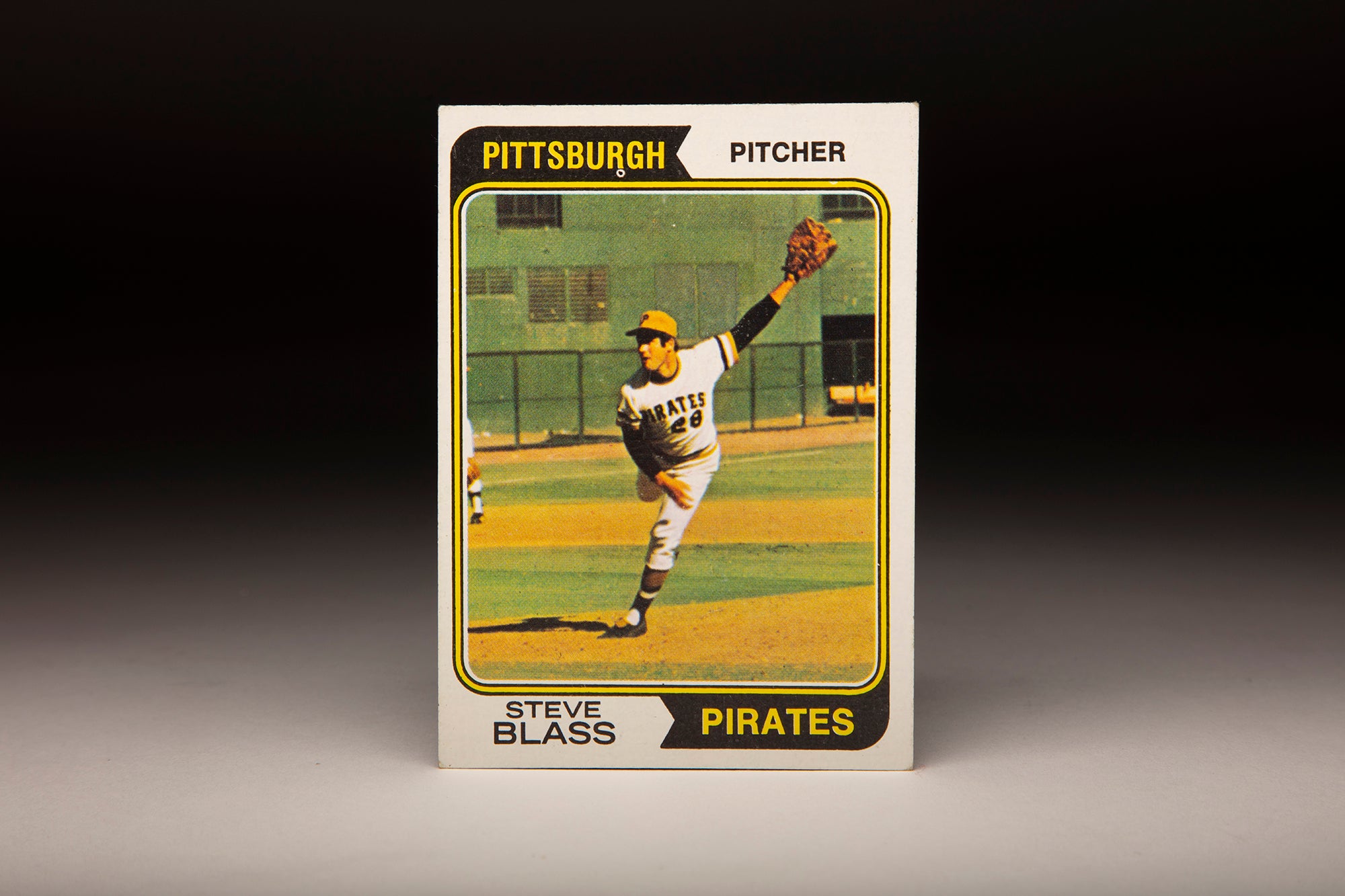

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Steve Blass

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Chuck Goggin

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Boog Powell