- Home

- Our Stories

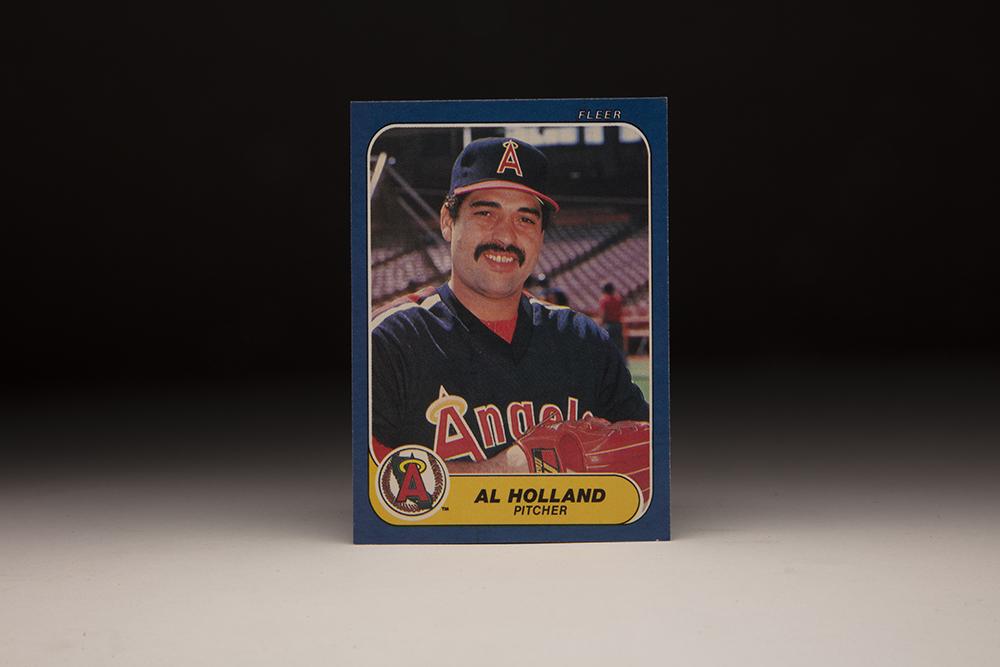

- #CardCorner: 1986 Fleer Al Holland

#CardCorner: 1986 Fleer Al Holland

There was nothing subtle about Al Holland.

For most of his 10 seasons in the big leagues, Holland’s approach was simple: Here’s the fastball, see if you can hit it.

The former running back at North Carolina A&T played baseball with a football mentality.

Alfred Willis Holland was born Aug. 16, 1952, in Roanoke, Va. One of four boys raised by a single mother, he earned a scholarship to play football at North Carolina A&T, a historically Black university located in Greensboro, N.C. Arriving on campus as a quarterback, Holland found success as a left-footed punter and saw action under center before moving to running back. He played four years for the Aggies from 1971-74, helping the team transition to the new Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference.

North Carolina A&T went 8-2 during the 1972 season and played for the MEAC title and a Pelican Bowl berth in the game’s final season, falling to North Carolina Central 9-7 on a last-minute field goal. The Aggies would not post a winning record in Holland’s final two seasons, but Holland remained a stalwart on the gridiron while earning All-American honors on the diamond as a hard-throwing pitcher.

Selected by the Rangers in the 30th round of the 1974 MLB Draft, Holland turned down a bonus offer of $2,000 and returned to school. The Padres took Holland in the fourth round of the 1975 January draft, but again Holland opted not to sign.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Then, following his graduation, Holland’s name was not called in the 1975 June MLB Draft. He attended a Pirates tryout camp in Charlotte, N.C., impressed Pittsburgh scout Branch Rickey III – grandson of the Hall of Fame executive – and signed on June 28, 1975.

The Pirates sent Holland to their Gulf Coast League affiliate, where he posted a 1.13 ERA in 40 innings. He then moved up to Niagara Falls of the New York-Penn League, where he was 4-2 with a 2.57 ERA over six starts.

In 1976, the Pirates converted Holland into a reliever. He went 4-2 with 13 saves and a 2.96 ERA in 39 games for Class A Salem, then blitzed through the Double-A and Triple-A levels a year later – going 10-5 with eight saves and a 2.88 ERA over 48 games for Shreveport and Columbus.

On Sept. 5, 1977, Holland made his big league debut, pitching a scoreless inning against the Phillies. He appeared in just one more game that year as the Pirates battled Philadelphia down the stretch, falling five games short of the NL East title.

“I pitched in two games for the Pirates in four years,” Holland told the Philadelphia Daily News. “I had good minor league years and great Spring Trainings, but they never gave me my shot.

“The Pirates were good to me in some ways, though. Larry Sherry was the minor league pitching coach. He converted me into a relief pitcher. And Grant Jackson taught me a lot every spring, how to conduct myself and how to approach pitching.”

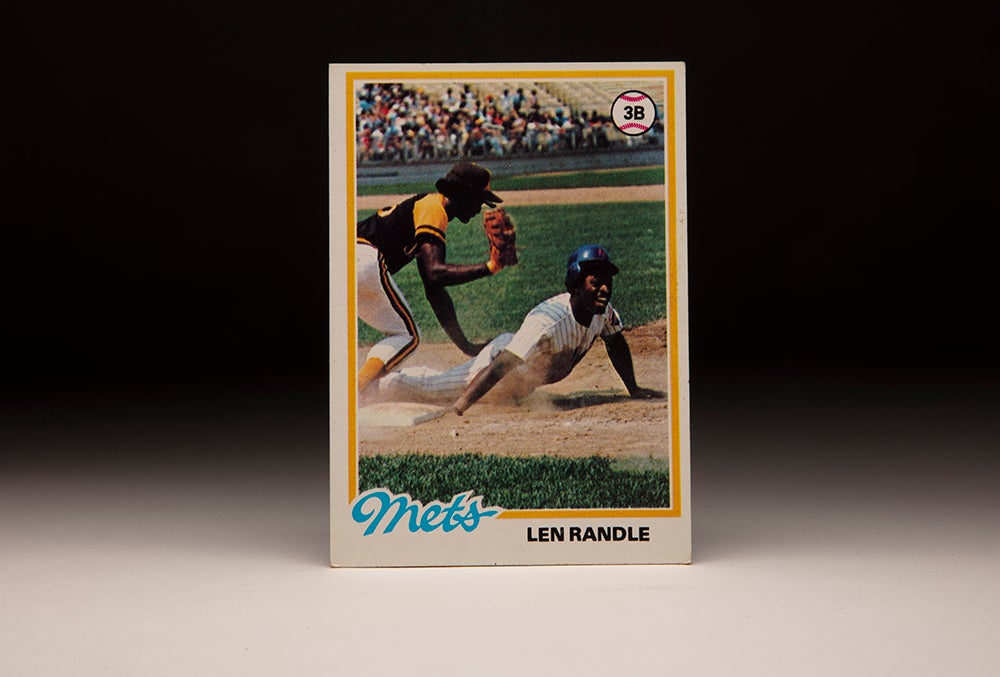

But most of Holland’s appearances for Triple-A Columbus in 1978 came as a starting pitcher, and he struggled to an 8-5 mark and 5.34 ERA. Then after going 4-6 with a 4.68 ERA in 16 games with Portland – where the Pirates had relocated their Triple-A team – in 1979, Holland was dealt to the Giants along with Fred Breining and Ed Whitson in exchange for Bill Madlock, Lenny Randle and Dave Roberts.

The deal came exactly four years to the day after Holland signed with Pittsburgh and was meant to bolster a Pirates team that was rounding into shape after a slow start to the season. Madlock and Roberts did indeed help the Pirates win the World Series that fall. But for Holland, it was a trade that ignited his career.

“I had mixed emotions,” Holland told the San Francisco Examiner of the trade. “I wanted to stay with the Pirates organization, but then I thought maybe there’s going to be a new life for me.”

Holland stayed in the Pacific Coast League after the trade, heading south to Phoenix. He pitched in 13 games there and then three more with the Giants in September, allowing no runs over seven innings while striking out seven.

That performance earned Holland an invitation to Spring Training with the Giants in 1980. Manager Dave Bristol was so impressed – Holland allowed just one earned run in seven Cactus League appearances – that he kept Holland as one of his five bullpen arms to start the season.

“It looks like Holland has a rubber arm that we could use every other day,” Bristol told United Press International.

Bristol deployed Holland in low-leverage situations at first, and Holland did not allow an earned run until May 7 – when Bristol used him in his third game in three days. Holland picked up his first big league win on May 16, appeared in 13 games in the month of July alone and was working on a 1.07 ERA as late as Aug. 31. He completed the season with a 5-3 record and seven saves to go with a 1.75 ERA in 54 appearances, striking out 65 batters in 82.1 innings.

“That’s because,” Bristol told the San Francisco Examiner of his frequent use of Holland, “he has a bellyful of guts.”

Holland finished seventh in the National League Rookie of the Year voting.

With his roster place now secure, Holland worked on the basics in Spring Training of 1981 as the Giants adjusted to their new manager, Frank Robinson – who would become the first Black skipper in National League history. Robinson called on Holland repeatedly early in the season but Holland could not duplicate his 1980 numbers. He had a 6.75 ERA through May 16 when he began toying with a slider taught to him by Giants bullpen coach John Van Ornum.

On May 17, Holland picked up the win with three hitless innings of relief against the Expos. He came back with four scoreless innings against the Mets two days later.

“Until now, I’ve been a one-dimensional pitcher,” Holland told the San Francisco Examiner. “I would throw fastballs, and then I would mix in a curve, and they might jump on the curve. But people don’t jump on the slider.

“You’ve got to have a lot of this (while pointing at his heart). I didn’t have to learn that from anybody. I’ve always had it.”

Holland continued to baffle hitters after the season resumed following the strike, allowing runs in just two of his 11 appearances in August. His final three appearances of the season came as a starter while subbing for the injured Vida Blue, and Holland worked a total of 21.2 innings with a 2.08 ERA. He finished the year with a 7-5 record and seven saves to go with a 2.41 ERA and 78 strikeouts over 100.2 innings.

Robinson kept Holland in the starting rotation at the beginning of the 1982 season, and he was 2-3 with a 3.76 ERA through seven starts when a hamstring injury suffered while running the bases sent him to the disabled list. When he returned in June, Robinson put Holland back in the bullpen.

“Every time we called the bullpen, Al would start warming up,” Frank Robinson told the Philadelphia Daily News. “Didn’t matter who we were calling for. A lot of times we had to say: ‘No, not you.’ But the point is, he wanted the ball.”

Holland went 7-3 with five saves and a 3.38 ERA in 1982. From Sept. 9 through Sept. 26, Holland pitched 17.2 hitless innings, facing 58 batters – three who reached on errors and two who walked. The other 53 were retired.

Then on Dec. 14, the Giants – who were a surprising 87-75 in 1982 – sent Holland and Joe Morgan to the Phillies in exchange for Mark Davis, Mike Krukow and minor leaguer C. L. Penigar.

“I liked it,” Holland told the Philadelphia Daily News of playing at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. “I liked it because nobody else liked it. I used it to my advantage, busted all those right-handed hitters in on the fists. Yeah, I’m gonna miss it. But not enough to make me feel bad about coming to the Phillies. I think it’s a great opportunity for me. I’m hoping the Phillies have enough confidence in me to let me do the job against everybody.”

Holland was expected to assume the closer’s role for the Phillies after signing a new three-year deal following the trade but battled shoulder soreness throughout Spring Training – an injury that delayed his regular season debut until May 1.

“I’ve never had anything like this in my shoulder before,” Holland told the Camden (N.J.) Courier-Post. “During the year, I’m going to pitch with pain. But sometimes you just have to say: ‘Wait a minute. I don’t want to take a chance on a permanent injury.’”

The Phillies began the season in a rut that cost manager Pat Corrales his job. But once Paul Owens took over in July, Philadelphia began playing better baseball. Holland was a big part of that resurgence, appearing in 29 games in August and September while posting 14 saves and a 2.25 ERA.

The Phillies won the NL East and advanced to the NLCS vs. the Dodgers, where Holland saved Game 1 and closed out Game 4 with 1.2 scoreless innings in a 7-2 win that gave Philadelphia the pennant.

When Holland struck out Bill Russell to end the game, the pitcher known as “Mr. T” leapt into the arms of teammate Mike Schmidt and thrust his fist in the air in celebration.

“Who would have thought we would end up this way?” Holland told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “Hell, maybe we should start the season in August from now on.”

Holland pitched two more games in the World Series against Baltimore, saving the Phillies’ win in Game 1. But in Game 3, Holland was unable to squelch a seventh-inning rally in relief of Steve Carlton as an Iván De Jesus error allowed the go-ahead run to score in what became a 3-2 Philadelphia loss. Holland closed the game with two perfect innings but did not appear in Games 4 or 5 as Baltimore captured the title.

Overall, Holland was 8-4 with 25 saves and a 2.26 ERA in 1983. He became just the seventh lefty in big league history with at least 100 strikeouts in a season where he did not start a single game, and his 91.2 innings worked were the fewest of any of the pitchers on that list. He won the 1983 NL Rolaids Relief Award, finished sixth in the NL Cy Young Award voting and ninth in the NL MVP race.

It would be the peak of a career that would see its share of challenges in the coming years.

In 1984, Holland was named to his first All-Star Game and was 5-6 with 25 saves and a 2.40 ERA in 55 games through Aug. 9. But the workload took its toll and Holland appeared in just four games in September, finishing the year with a 5-10 record, 29 saves and a 3.39 ERA.

After three appearances in 1985, the Phillies traded Holland and minor leaguer Frankie Griffin to the Pirates for Kent Tekulve in a deal that featured two veteran relievers.

“I play baseball and I have no control over what happens, but this was a total shock to me,” Holland told the Morning News of Wilmington, Del. “Now I’ve got the incentive and determination to prove to the Phillies that they made a mistake.”

Entering the final year of his contract, the 32-year-old Holland was clearly not in the Phillies’ future plans.

“Here’s a guy who’s on the last year of his contract and he reports (to Spring Training) at 242 pounds,” Phillies general manager Bill Giles told the Morning News. “He can’t be motivated too much.”

Holland joined a Pirates bullpen that featured John Candelaria as the closer and right-handers Cecilio Guante and Don Robinson in supporting roles. Holland appeared in 38 games, going 1-3 with four saves and a 3.38 ERA for a Pirates team that would eventually lose 104 times that season.

Holland wasn’t around for the final two months of losses because on Aug. 2, he was traded along with Candelaria and George Hendrick to the Angels for Mike Brown, Pat Clements and Bob Kipper.

In September, Holland was called to testify in a federal drug trial of a clubhouse caterer charged with distribution narcotics. After going 0-1 with a 1.48 ERA in 15 games for the Angels, Holland received a 60-day suspension from MLB commissioner Peter Ueberroth but was allowed to avoid the suspension by donating money to anti-drug campaigns and participating in community service.

He signed with the Yankees on Feb. 6, 1986, was released on April 4 and then re-signed by New York six days later before being released again in August. He posted a 1-0 record and 5.09 ERA over 25 appearances that season – shuttling back and forth between Triple-A before returning to the Yankees on a free agent deal on April 10, 1987. After once again pitching in Triple-A, Holland made three appearances in August – allowing 10 runs in 6.1 innings of work in the final big league games of his career. Holland pitched in the Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1989 and later served as a minor league pitching coach. In 10 big league seasons, he totaled 78 saves to go with a 34-30 record and 2.98 ERA over 384 games. For the former college football player who made it to the majors via the undrafted free agent route, it was a successful legacy based on a simple formula. “Just give me the ball and the chance to blow some dude away,” Holland said. “That’s why I play the game.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

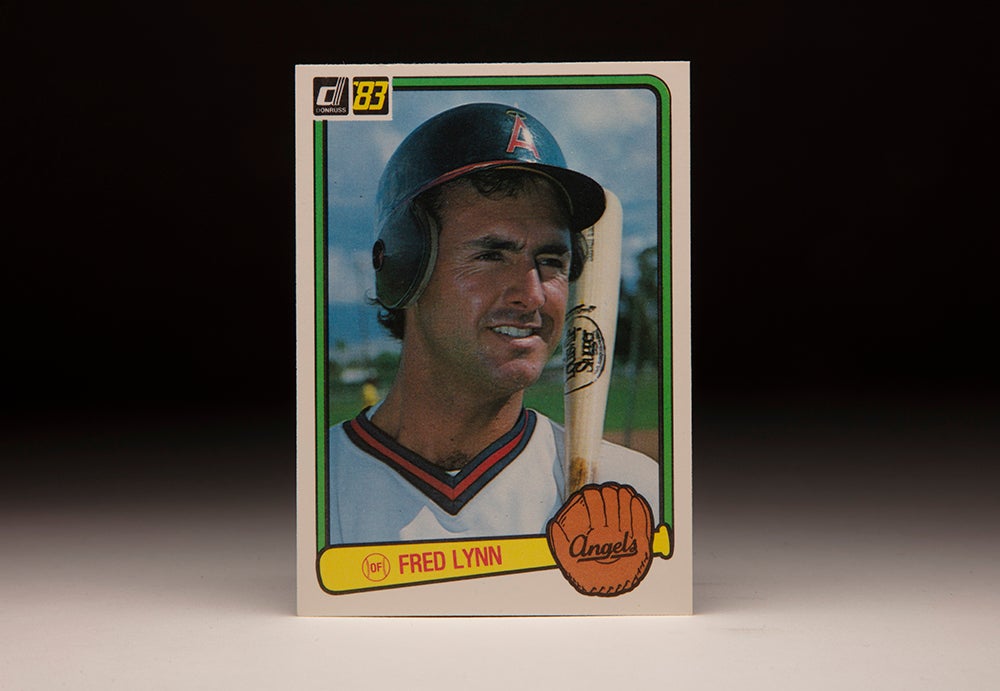

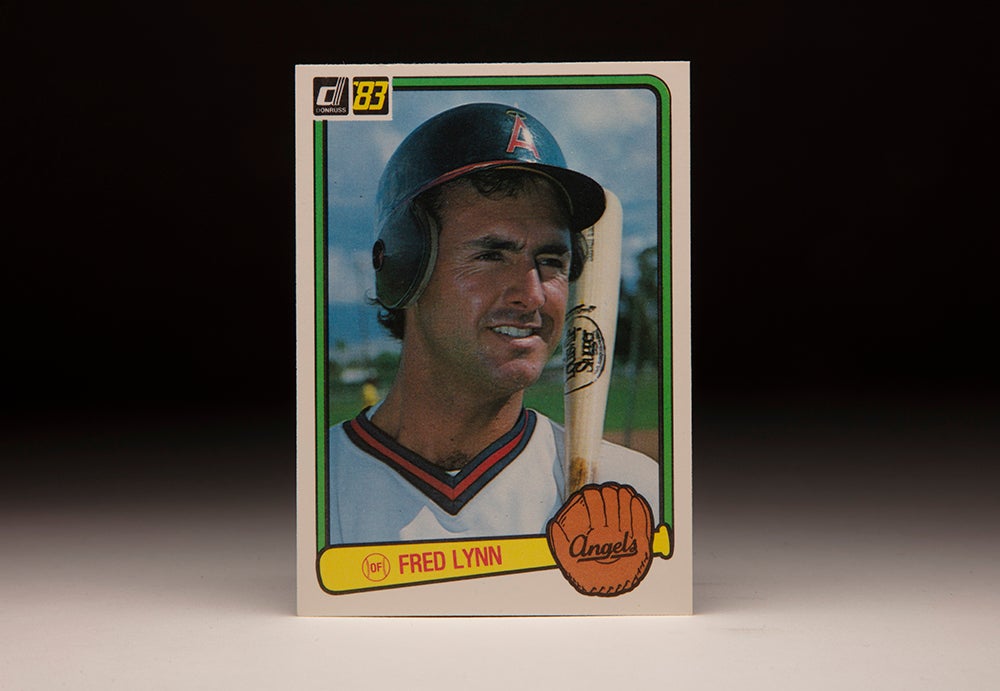

#CardCorner: 1983 Donruss Fred Lynn

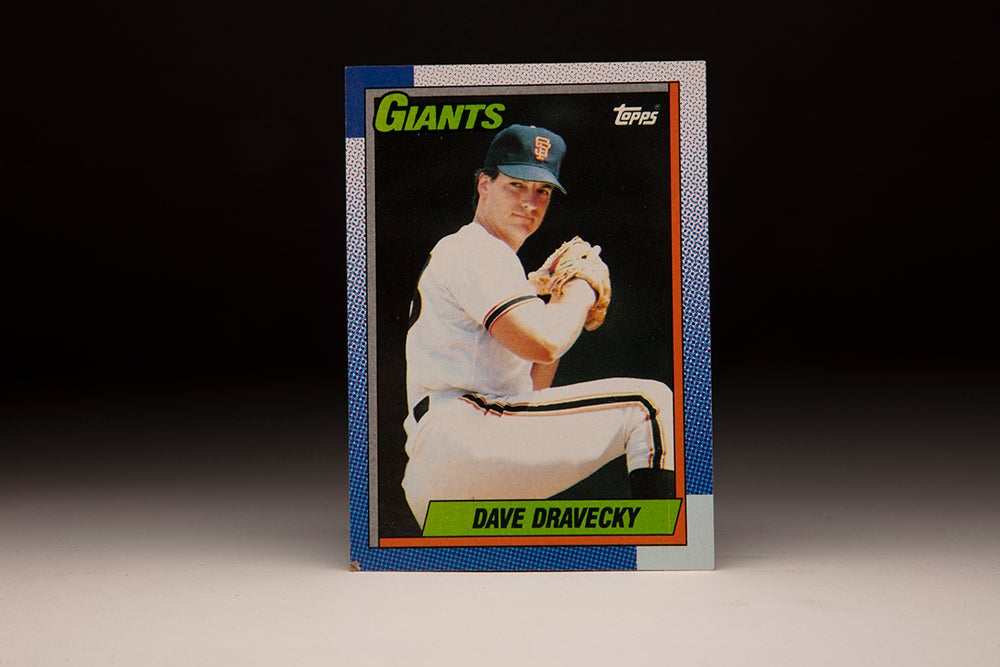

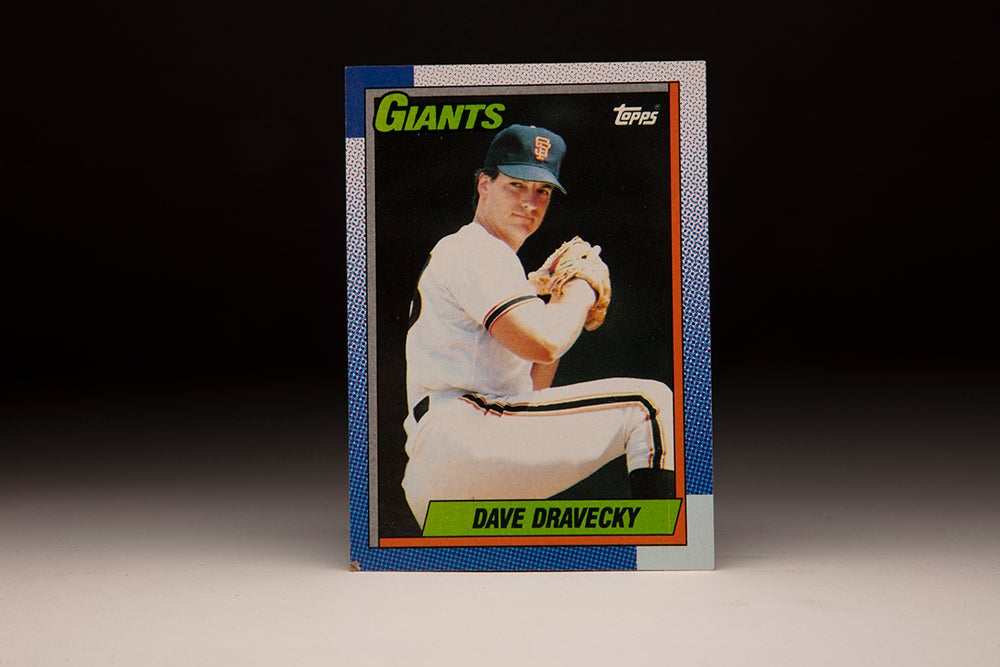

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Dave Dravecky

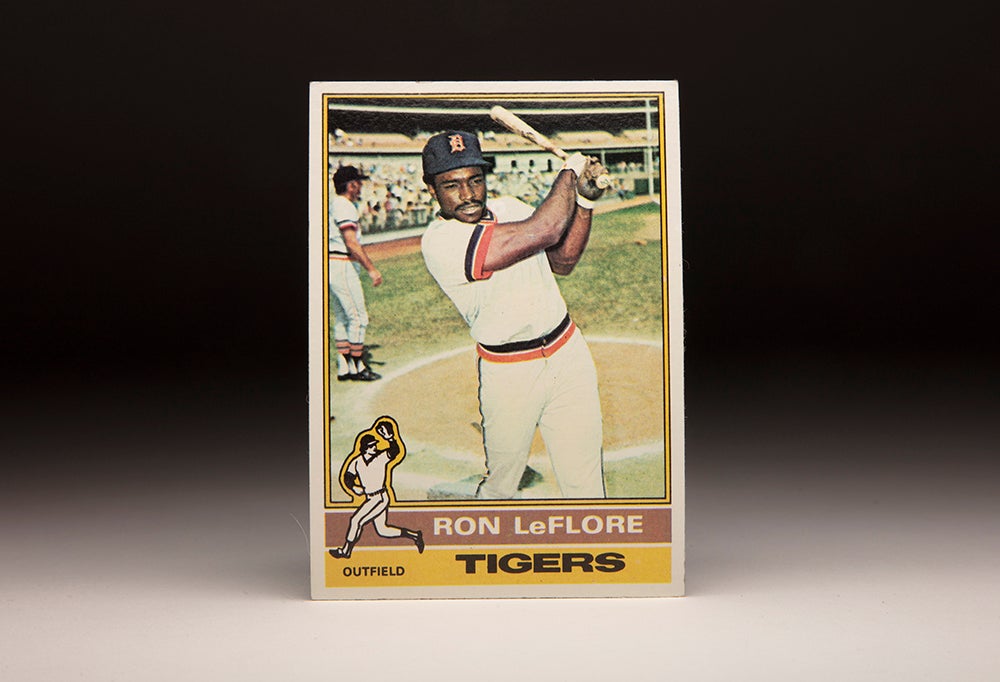

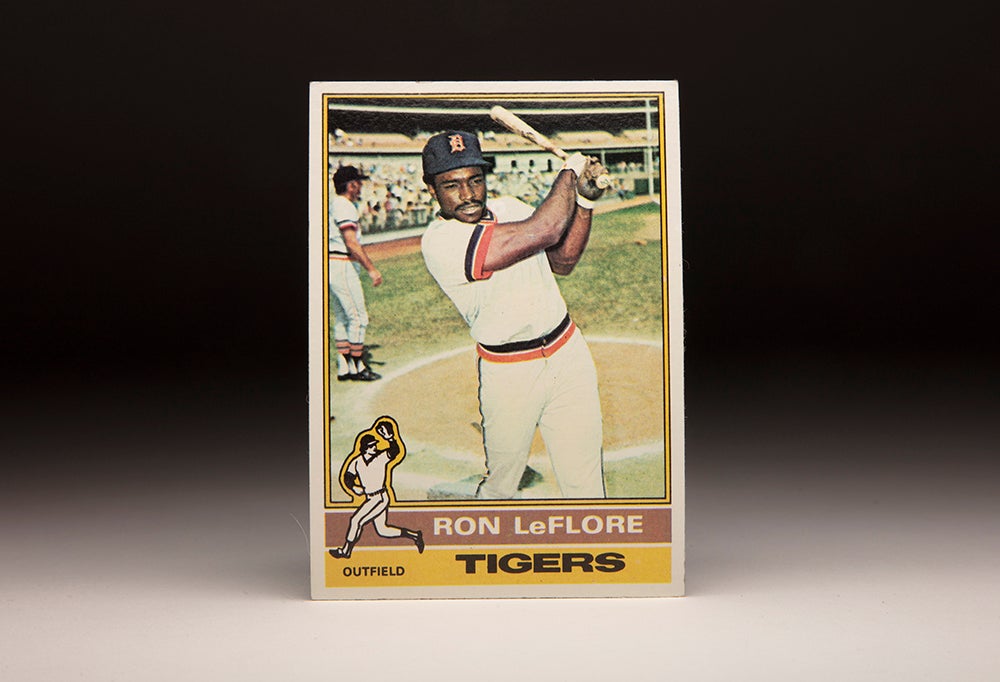

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Ron LeFlore

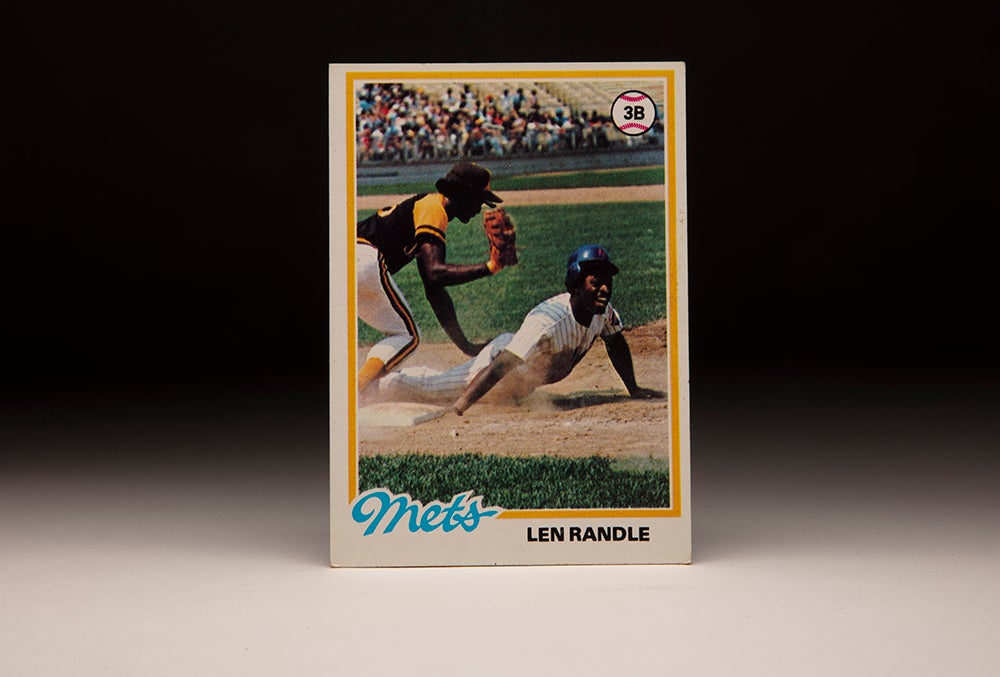

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Lenny Randle

#CardCorner: 1983 Donruss Fred Lynn

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Dave Dravecky

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Ron LeFlore