- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1976 Topps Ron LeFlore

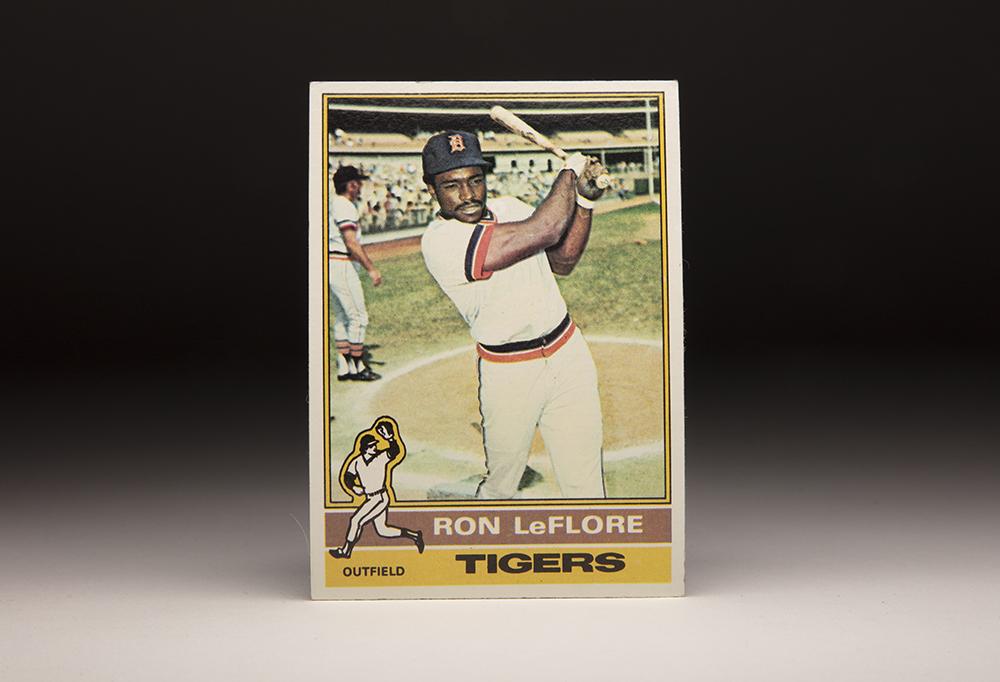

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Ron LeFlore

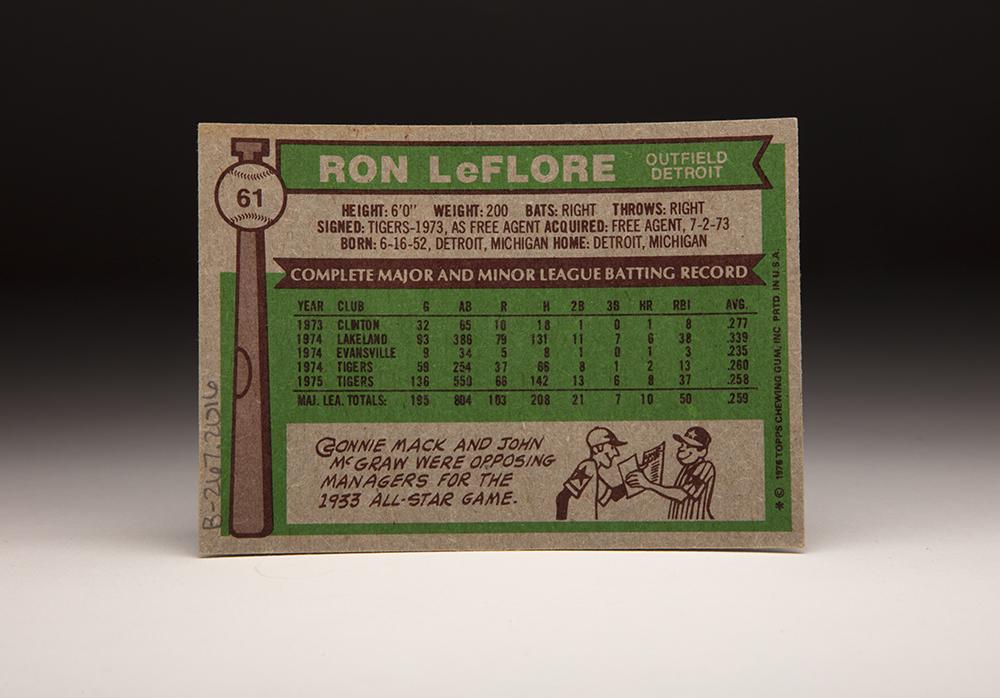

Ron LeFlore’s 1976 Topps card lists him as playing much of the 1975 season at just 22 years of age – a remarkable achievement for any player, let alone someone who had never participated in youth baseball.

It was an untruth in a career that even without misinformation became one of the most startling stories in the history of the game.

LeFlore’s real birthdate was June 16, 1948 – meaning he was 27 years old for most of the 1975 season. Growing up in Detroit, LeFlore began committing petty crimes at a young age.

“I just had the devil in me,” LeFlore told author Peter Golenbock for “The Forever Boys”, a book on the Senior Professional Baseball Association.

“For instance, my parents would go to sleep, and I’d jump out a second-story window and go out and rob with my friends. My parents never knew what I was doing – until I got caught.”

LeFlore told Golenbock that he soon became addicted to heroin. In December of 1966, in an attempt to score money to buy drugs, LeFlore and his friends robbed a bar that was known to have cash on hand at all times. They were quickly arrested and LeFlore, then 18, was convicted and sentenced to 5-to-15 years at the State Prison of Southern Michigan in Jackson.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

“I wouldn’t wish prison on anyone, because it’s the most injurious thing in the world for you to be locked up in a cell,” LeFlore told Golenbock. “But you get a chance to get into yourself and find out who you really are and what you want to do in life.”

What LeFlore found was that his athletic ability was better than almost all of his peers. He quickly made a name for himself in prison intramural sports, refurbishing the talents that first surfaced at East Detroit High School – where he was a teammate of future NFL running back John “Frenchy” Fuqua.

While in prison, LeFlore wrote a letter to Detroit Tigers general manager Jim Campbell, asking for a tryout. Campbell declined the offer but LeFlore persisted, eventually connecting through a friend with Tigers manager Billy Martin. On June 15, 1973 – before a game against the Minnesota Twins – Martin agreed to watch LeFlore work out at Tiger Stadium after LeFlore had arranged for a prison furlough.

While in prison, Ron LeFlore wrote a letter to Detroit Tigers general manager Jim Campbell, asking for a tryout. Campbell declined the offer but LeFlore persisted, eventually connecting through a friend with Tigers manager Billy Martin. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

LeFlore impressed Martin enough that the Tigers invited him back for another look the following week. The Tigers agreed to sign LeFlore if he was released from prison, and the state granted LeFlore probation after six-and-a-half years of his sentence. On July 2, the Tigers gave LeFlore a $10,000 bonus and sent him and his parole officer to Clinton of the Midwest League.

LeFlore hit .277 in 32 games that summer for the Clinton Pilots, where his manager was future Tigers skipper Jim Leyland. LeFlore started the 1974 season with Class A Lakeland, and he tore up the Florida State League by hitting .339 with 42 stolen bases and 79 runs scored in 93 games. That earned him a promotion to Triple-A Evansville.

On July 30, Tigers center fielder Mickey Stanley was hit on the right hand by a pitch from Boston’s Reggie Cleveland. The resulting broken bone sidelined Stanley until late September.

“We haven’t been getting many breaks this season,” new Tigers manager Ralph Houk told the Associated Press after Stanley’s injury.

But Houk, who was impressed by LeFlore in Spring Training, was about to have luck on his side. On Aug. 1, the Tigers brought LeFlore to the majors after he had played just nine games at Evansville. After a slow start, LeFlore finished the season hitting .260 with 37 runs scored and 23 steals in 59 games. He had multiple hits in each of his last six games of the year.

In Spring Training of 1975, Houk moved Stanley to a bench role and inserted LeFlore into the starting lineup as the team’s center fielder.

“(Freedom) is the most precious thing in the world,” LeFlore told United Press International that spring in a story about his life that ran in hundreds of papers across the country. The article listed the 26-year-old LeFlore as 22.

LeFlore started the season on a hot streak and was hitting .289 as late as July 17 when his lack of experience – he had fewer than 550 minor league plate appearances when he debuted in the big leagues – caught up with him. He hit just .204 the rest of the way but still finished the year with a .258 batting average, 28 stolen bases and 66 runs scored in 136 games.

In the spring of 1976, the Associated Press reported LeFlore’s true birthdate of 1948. But regardless of his age, LeFlore was on track to become a star.

“Frankly, it’s of no concern to me,” Campbell told the AP. “I could care less…the only concern I have is that he can play ball.”

LeFlore showed that was no problem, amassing a 30-game hit streak from April 17 – his first start of the year – through May 27 despite dealing with personal tragedy: His brother, Gerald, was shot and killed during a struggle over a rifle on April 23.

But LeFlore remained focused for the entire season, earning an All-Star Game selection and finishing with a .316 batting average, 93 runs scored and 58 stolen bases in just 139 games. A ruptured tendon in his right knee ended his season on Sept. 12 but LeFlore had shown he was one of baseball’s best young players.

The injury, which put LeFlore in a cast, slowed him in early 1977 – with his batting average stuck in the .230s into June. But LeFlore hit .360 after the All-Star Game and finished the year with a .325 batting average, 212 hits, 100 runs scored, 16 homers and 39 steals. He was arguably better in 1978, leading the majors with 126 runs scored and pacing the AL with 68 steals while hitting .297 with 12 homers and 62 RBI. He amassed a 27-game hitting streak in August and September, becoming just the 10th player in history with at least two hitting streaks of 27-or-more games. No one has done it since.

That year, a television movie based on LeFlore’s life aired on CBS. Titled “One in a Million: The Ron LeFlore Story” the film starred LeVar Burton and elevated LeFlore’s profile beyond the baseball world.

But following the 1978 season, Houk – who had supported LeFlore throughout his career – resigned. Les Moss took over for the 1979 campaign but was dismissed on June 12 and immediately replaced by Sparky Anderson. One of Anderson’s first moves was – as had been the policy in Cincinnati – to ban facial hair.

“I guess he thought I was being rebellious,” LeFlore told Peter Golenbock about his refusal to shave his mustache.

LeFlore hit .300 in 1979, stealing 78 bases and scoring 110 runs. But after the season, the Tigers traded LeFlore to the Expos in a one-for-one deal for left-handed pitcher Dan Schatzeder.

“I was upset,” LeFlore told Golenbock. “But what could I do about it? Nothing.”

What LeFlore did, however, was post one of the most prolific base-stealing seasons in baseball history.

The Expos, coming off a season where they finished just two games behind the NL East-leading Pittsburgh Pirates, believed LeFlore would be the difference in 1980. Manager Dick Williams was known for being a disciplinarian, but Williams – who had a mustache of his own – got along with LeFlore and gave him the green light on the base paths.

LeFlore stole an NL-best 97 bases, battling Pittsburgh’s Omar Moreno for the title throughout the season. Moreno stole his 96th base on Oct. 1, giving him a two-steal lead over LeFlore. But Moreno was shut out in the Pirates’ final three games of the year while LeFlore stole one base in the season’s penultimate game – a contest where the Phillies beat Montreal to wrap up the NL East title – and two more in the season’s final game to take the crown.

Moreno’s 96 steals were the most ever by a player who did not lead his league. LeFlore, meanwhile, became just the fourth player in the modern era (post 1900) with at least 97 steals, joining Lou Brock (118 in 1974), Maury Wills (104 in 1962) and Rickey Henderson (100 in 1980).

LeFlore and his wife, Sara, welcomed a baby boy in August. But the family would not stay in Montreal long: Following the season, LeFlore became a free agent and signed a three-year, $2.425 million contract with the White Sox.

Soon after the deal was announced, reports surfaced that the Expos had no desire to retain LeFlore. A hand injury – suffered after running into the left field wall at Olympic Stadium – limited LeFlore to pinch running appearances in the final three weeks of the season – and LeFlore reportedly showed up for key games less than an hour before first pitch.

“I won’t go into details,” Expos general manager John McHale told the San Francisco Examiner. “But people wouldn’t believe all the problems he caused during the season, and not just peccadillos – major problems.”

LeFlore played left field for the White Sox nearly every day in 1981, hitting .246 with 36 steals in 82 games in a season shortened by the strike. He began the 1982 season as Chicago’s center fielder and was hitting .300 deep into May when he began to feel the effects of covering the vast center field acreage at Comiskey Park. Manager Tony La Russa began to platoon the right-handed hitting LeFlore with lefty Rudy Law despite his misgivings that LeFlore might not respond to such a set up.

“Rudy Law’s been sparking our club offensively and defensively,” La Russa told the Chicago Tribune. “I know Ronnie’s been raring to go. That job is out there to be won, and the guy who plays the best gets the most playing time.”

That turned out to be Law, who ensconced himself in center as LeFlore rode the bench. LeFlore was suspended for three days in July for showing up late for a game, appeared in just one game in the month of September and was arrested by Chicago police on Sept. 30 and charged with two counts of illegal possession of a controlled substance and weapons charges. Despite those obstacles, he still hit .287 with 28 steals and 58 runs scored in 91 games.

On April 2, 1983 – two days before the start of a season that would see the White Sox win the AL West title – Chicago released LeFlore. “I guess that’s the way of really putting you down,” LeFlore told Golenbock of his release on the eve of the 1983 season. LeFlore played in the Puerto Rican Winter League following the 1983 season with the hope of returning in 1984, but an injury to his hip derailed those plans. At 35, his career was over. LeFlore suffered through depression and substance abuse issues after his career ended but made a brief comeback in the Senior Professional Baseball Association in the winter of 1989-90, playing for the St. Petersburg Pelicans and Bradenton Explorers. After the league folded, LeFlore continued to play in amateur leagues around the Tampa area. He would later coach and manage in the independent Frontier League and run a baseball school in his adopted hometown of St. Petersburg, Fla. Over nine big league seasons, LeFlore hit .288 with 731 runs scored, 1,283 hits and 455 stolen bases. He is the only player in big league history with more than 400 steals and fewer than nine seasons played. “I don’t go to church every day, but I do believe there is someone behind me,” LeFlore told Golenbock. “If not, I don’t think I would be alive today.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

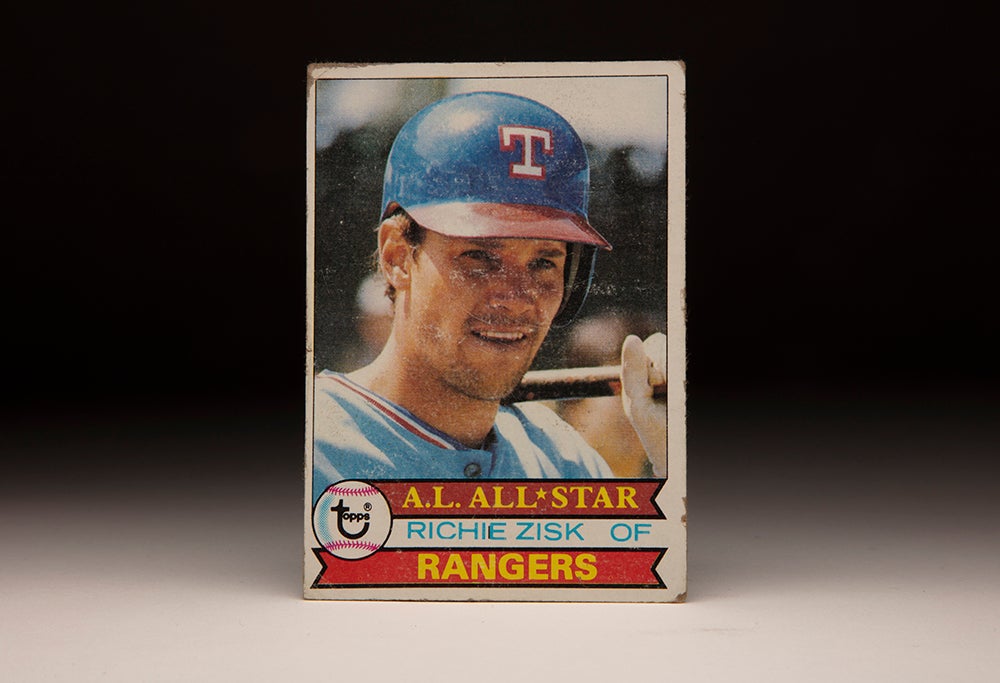

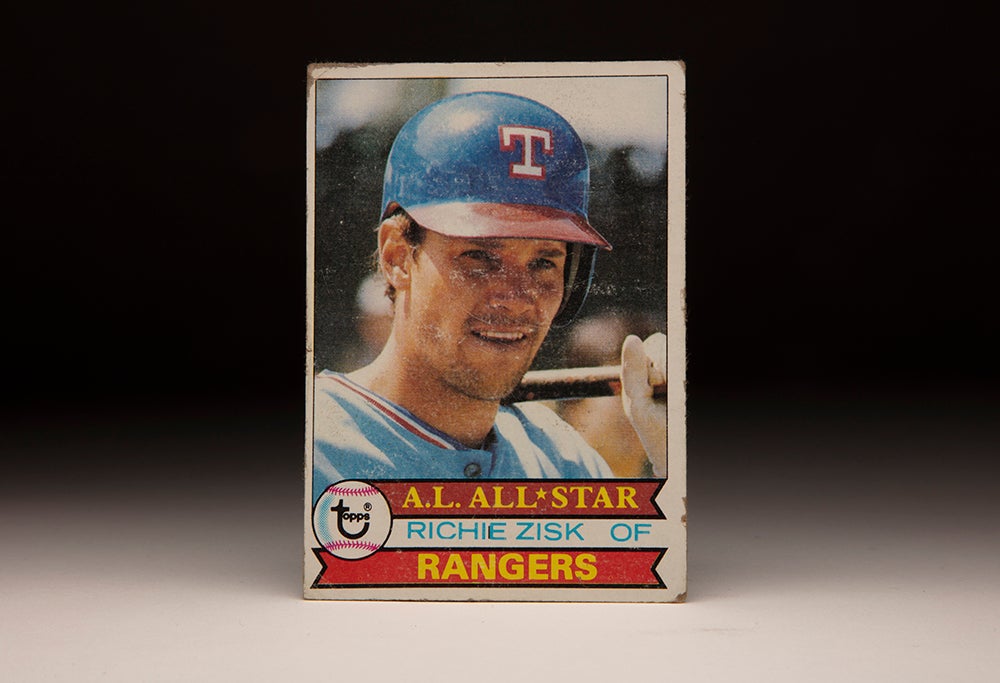

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Richie Zisk

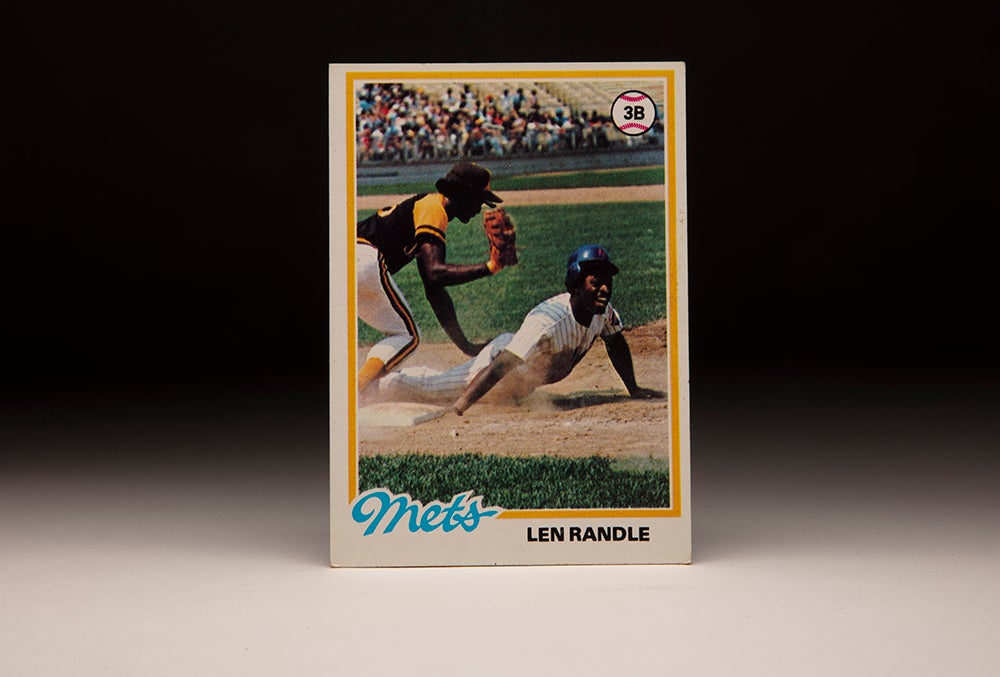

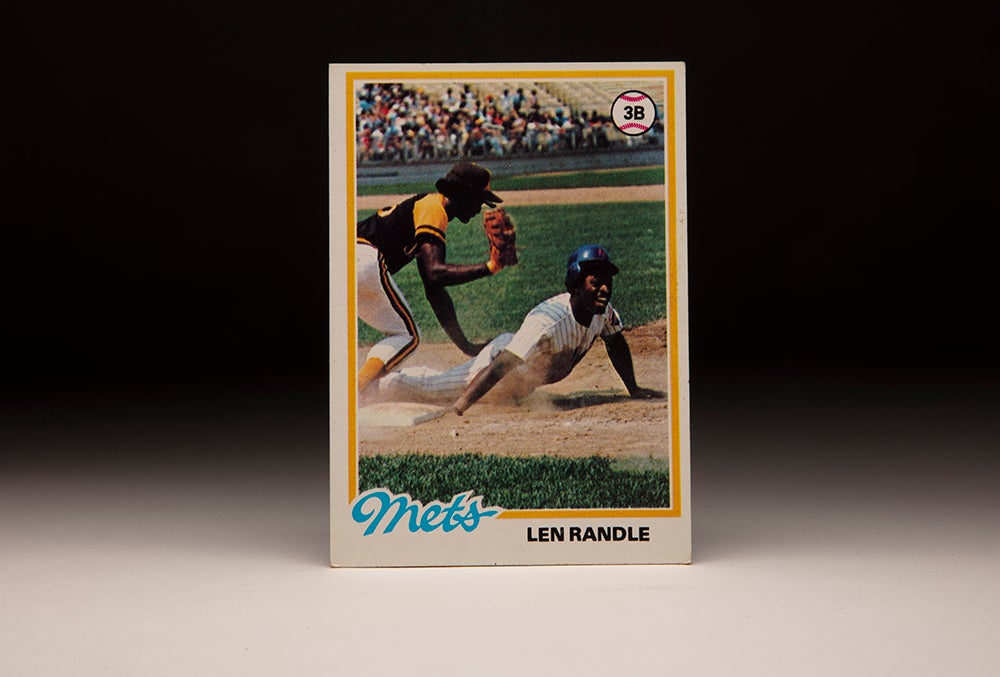

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Lenny Randle

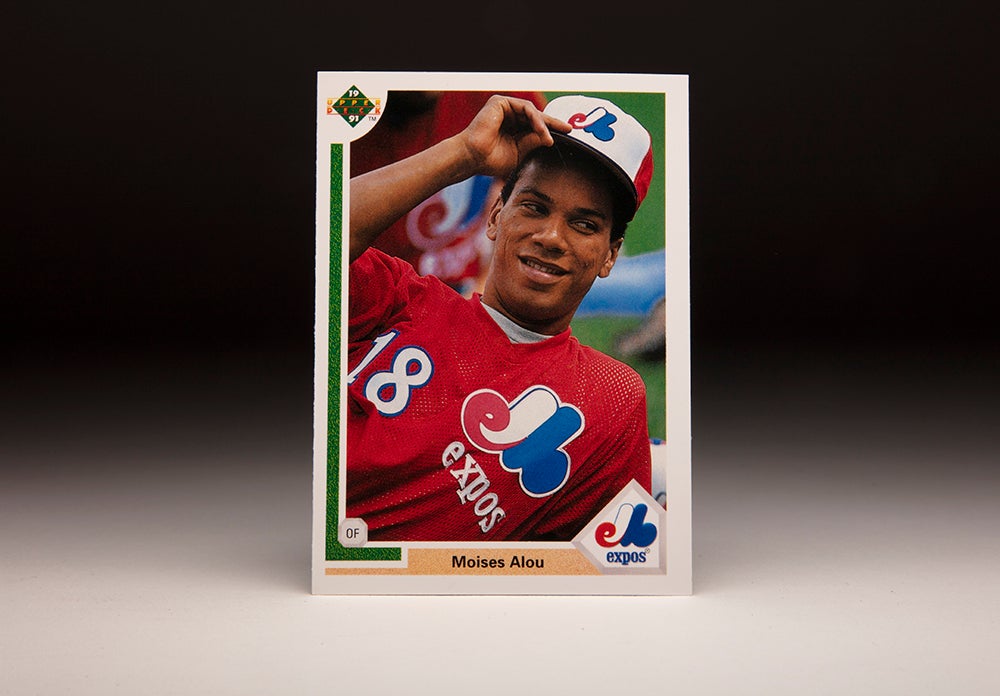

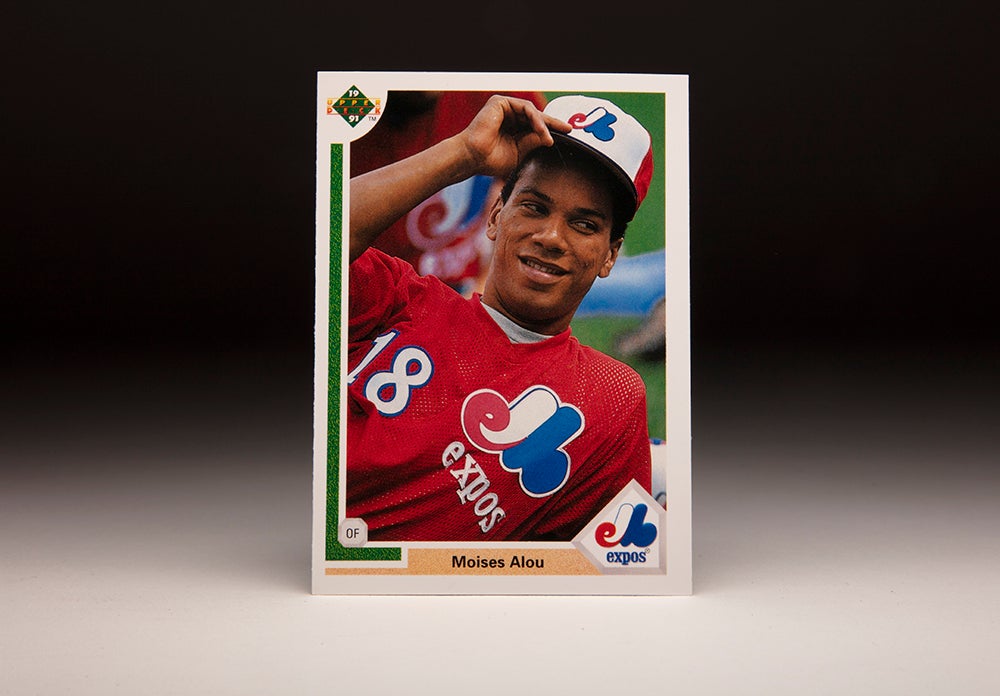

#CardCorner: 1991 Upper Deck Moises Alou

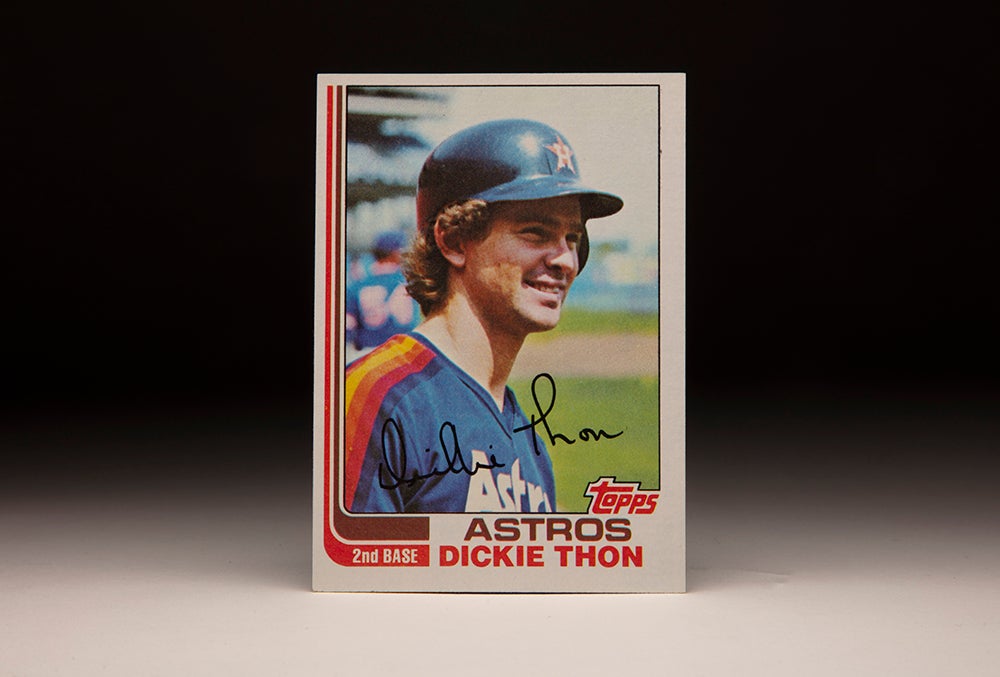

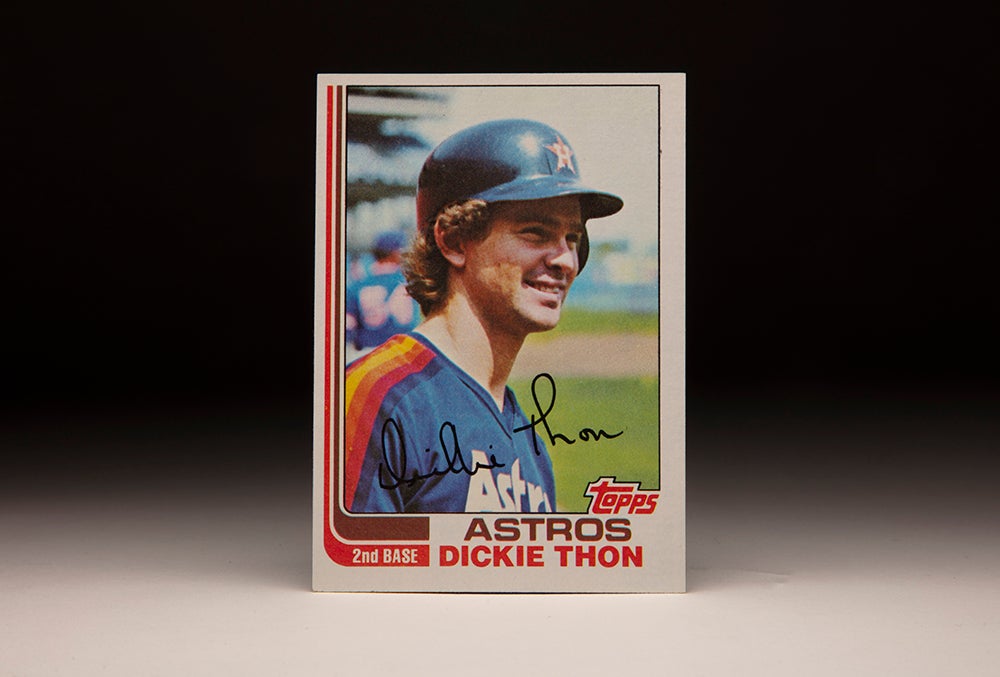

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Dickie Thon

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Richie Zisk

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Lenny Randle

#CardCorner: 1991 Upper Deck Moises Alou