- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1991 Upper Deck Moises Alou

#CardCorner: 1991 Upper Deck Moises Alou

He is one of only 10 players in history with the following combination of career statistics: 300 homers, a .300 batting average and 100 stolen bases.

But Moises Alou is completely unique in comparison to the other nine players on that list. For unlike Hank Aaron, George Brett, Lou Gehrig, Vladimir Guerrero, Rogers Hornsby, Chipper Jones, Willie Mays, Babe Ruth and Larry Walker, Alou is not a Hall of Famer.

Alou is, however, baseball royalty in the Dominican Republic – and was one of the most successful players of his era.

Born July 3, 1966, in Atlanta, Ga., Alou is the son of Felipe Alou – a Dominican hero who was playing for the Braves when Moises was born. The younger Alou grew up a basketball fan – his high school in Santo Domingo did not have a baseball team – but began to concentrate on baseball as he grew into his 6-foot-3, 185-pound frame.

“I wasn’t going to make the NBA,” Alou told the Palm Beach Post.

Alou’s mother and father were divorced when he was three, and Alou spent much of his childhood with his mother in the Dominican Republic.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

But with baseball roots that ran deep – his uncles Matty and Jesús also played in the big leagues – Moises had little trouble transitioning to the diamond. Felipe joined the Expos’ coaching staff after his 17-year MLB playing career and became a respected minor league manager, giving Moises a chance to learn pro baseball at an early age.

“I realized he could play (baseball) for real when I was managing (Triple-A) Indianapolis in 1985,” Felipe Alou told the Palm Beach Post. “He was going to school in California and came for summer vacation. I let him take some (batting practice) with the team, and he worked out on the field. He had a stronger arm than the guys we had there. I could see he loved the game.”

After high school, Moises played for Cañada College in Redwood City, Calif., working with Jesús Alou on learning the game. The Pirates took notice and grabbed Alou with the second overall pick in the January 1986 MLB Draft, which was then used mostly as a vehicle to the pros for junior college players.

“He didn’t want me to sign,” Alou told the York (Pa.) Dispatch about his father’s advice after he was drafted. “But he said: ‘It’s up to you.’ I got a pretty good offer, so I signed.”

Alou struggled in his first two seasons in the minors before hitting .313 with 24 steals for Class A Augusta in 1988. Prior to that season, Alou played winter ball in the Dominican Republic for the first time.

“It was the toughest year for me,” Alou told the Palm Beach Post. “It was the first time I had played in an organized league down there, and people expected me to do so well. They expected me to be as good as my dad.”

But with that experience came seasoning that transformed Alou. He played the 1989 campaign for both Class A Salem and Double-A Harrisburg, hitting .299 with 17 homers, 72 RBI and 20 steals in 140 games.

Then in 1990, Alou began the season in Harrisburg before earning a promotion to Triple-A Buffalo. On July 26, the Pirates brought the right-handed hitting Alou to the majors, sending down switch-hitting Orlando Merced – who was much better as a lefty hitter – as they embarked on a stretch where they would face several left-handed starters.

“Bill Virdon likes (Alou), and I respect Bill’s opinion,” Pirates manager Jim Leyland told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “He’s a good outfielder, and he’s got some pop.”

Alou debuted as a mid-game replacement for Barry Bonds on July 26, going 0-for-2 in a 12-4 Pittsburgh loss. Two nights later, Alou started in left field and led off, singling in the third inning off Bruce Ruffin for his first big league hit.

Alou was soon returned to Buffalo. Then on Aug. 8, the Pirates – in the midst of their first pennant race in almost a decade and with starting pitcher Bob Walk recently put on the disabled list – acquired pitcher Zane Smith from the Expos in exchange for Willie Greene, Scott Ruskin and a player to be named later.

That player to be named later turned out to be Alou.

Smith would go 6-2 with a 1.30 ERA down the stretch, helping the Pirates win the division and pitching effectively through the 1994 season. Alou, however, would turn into a six-time All-Star.

The Expos sent Alou to Triple-A Indianapolis, and he finished the minor league season with a .273 batting average, eight homers, 59 RBI and 20 steals in 126 games. Montreal called him up to the big leagues in September, and he totaled three hits in 15 at-bats. But while diving back to second base on a pickoff attempt, Alou tore the labrum in his right shoulder. The injury went undiagnosed until Spring Training, when the Expos announced that Alou would undergo corrective surgery by Dr. Frank Jobe.

“It’s not a career-threatening injury, but he’s very disappointed and so are we,” Expos general manager Dave Dombrowski told the Palm Beach Post. “He was swinging the bat very well.”

After missing the entire 1991 season, Alou returned to the Expos in 1992, first as a reserve before settling in as the team’s left fielder. He hit .282 with nine homers 56 RBI and 16 steals in 115 games, finishing second to the Dodgers’ Eric Karros in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting. And during the season, Felipe Alou became the Expos manager – replacing Tom Runnells and leading Montreal to 70 wins in its final 125 games.

“I’ve never heard anyone say a bad word about my dad,” Alou told the Palm Beach Post in 1992. “I don’t feel like I have to be the same as him, but I have to take care of what I do. I just want to get a chance to show what (I) can do.”

In 1993, the Expos made a push for the NL East title. Alou established himself as a star and was hitting .285 with 18 homers and 85 RBI when he tried to stretch a single into a double in the seventh inning against the Cardinals at Busch Stadium. But after rounding first, Alou retreated to the bag, caught his foot on the turf and buckled his left ankle. The resulting fracture left him sidelined for the remainder of the season – and Montreal finished three games behind the Phillies in second place with a record of 94-68.

“I heard it pop,” Cardinals first baseman Gregg Jefferies told the Philadelphia Daily News. “I never heard anything pop like that. It was awful.”

For Felipe Alou, watching his son in agony was almost too much to bear.

“I thought about when my other boy died,” said Alou, whose older son died in 1976 in a pool accident. “That’s the first thought I had. You give this game everything you have. And then (Moises) hurts himself, busting his (butt).”

But Alou returned to the Expos’ starting lineup on Opening Day of 1994 and received a huge ovation from the Olympic Stadium crowd when Montreal played its first home game of the season on April 8.

He had played in only six games during Spring Training while completing his rehabilitation.

“All I want is to stay healthy,” Alou told the Burlington (Vt.) Free Press, “and the rest will take care of itself.”

Alou and the Expos were the talk of baseball in 1994, with Montreal winning 74 of its first 114 games and Alou batting .339 with 22 homers, 31 doubles and 78 RBI. But when the strike ended the season, the Expos and Alou lost the chance to play in the postseason.

When baseball resumed, the team began trading some of its best talent – though Alou remained. But a biceps tear in his right arm limited him to just 93 games, including only one appearance after Aug. 18. And his family was struck by tragedy on July 28 when his father-in-law and brother-in-law were murdered in Brooklyn during an attempted robbery.

“It’s getting so every day I’m expecting something to go wrong,” Alou told the Montreal Gazette. “What’s next?”

Alou entered the 1996 season with free agency on the horizon, as the Expos were unable to sign him to a long-term extension. He hit .281 with 21 homers and 96 RBI that year, earning NL MVP votes for the second time following his third-place finish in 1994.

On Dec. 12, 1996, Alou signed a five-year, $25 million deal with the Marlins as part of a $89 million spending spree from owner Wayne Huizenga that also included signing Bobby Bonilla and Alex Fernandez.

“With the team we have right now,” Alou told the Miami Herald, “there’s no way we don’t at least go to the playoffs.”

Alou made sure he was correct when he had a banner season, hitting .292 with 23 homers, 88 runs scored and a team-leading 115 RBI. The Marlins won the NL Wild Card and swept the Giants in the NLDS before beating the Braves in six games in the NLCS. Alou had three hits in three games in his first Postseason action in the NLDS. He was just 1-for-15 in the NLCS, but that one hit was a three-run, first-inning double in Game 1 that set the tone for the series for the Marlins.

Then in the World Series against the Indians, Alou hit .321 with three homers, six runs scored and nine RBI. His three-run homer off Orel Hershiser in the sixth inning of Game 5 turned a 4-2 Marlins deficit into a 5-4 lead in a game Florida won 8-7. Many observers believed Alou – who battled the flu throughout a series that alternated between freezing cold temperatures in Cleveland and a Miami heatwave – should have been named the World Series MVP. But the award went to Liván Hernández, who won two games (albeit with a 5.27 ERA) in the Marlins’ seven-game victory.

Within a month after the World Series, Huizenga ordered the dismantling of his team. On Nov. 11, 1997, Alou was traded to the Astros in exchange for Manuel Barrios, Óscar Henriquez and Mark Johnson. Those three players combined to appear in 63 big league games for their careers.

“Moises Alou obviously is one of the premier players in the game today,” Astros general manager Gerry Hunsicker told the Associated Press. “It’s unusual that anybody can acquire a player of this magnitude.”

Alou did not disappoint Hunsicker and the Astros as he batted .312 with 38 homers and 124 RBI in 1998, earning his third All-Star Game selection and winning a Silver Slugger Award while finishing third in the NL MVP race. The Astros were heavily favored to make a deep postseason run after winning the NL Central title with 102 victories, but Houston lost to San Diego in the NLDS.

Then in February of 1999, Alou injured his left knee while training on a treadmill in the Dominican Republic. After initially thinking the injury would keep him out for a month or so, Alou learned that he had torn his anterior cruciate ligament – and that he would miss the entire season.

Returning in 2000, Alou – who would soon turn 34 – was better than ever at the plate, hitting .355 with 30 homers and 114 RBI in 126 games. He followed that up with a .331 batting average, 27 homers and 108 RBI in 2001 to lead the Astros to the NL Central title. But Houston was swept in the NLDS by the Braves. A free agent once again, Alou signed a three-year, $27 million deal with the Cubs on Dec. 19, 2001. Sammy Sosa, a native of San Pedro de Macoris in the Dominican Republic, spent several hours on the phone with Alou, convincing him to come to Chicago. “Everyone in the Dominican Republic is really excited about me being a Chicago Cub and me playing with Sammy,” Alou told the Associated Press. Alou hit .275 with 15 homers and 61 RBI in 2002 – battling rib cage, calf and back injuries – then helped power the Cubs to the NL Central title in 2003 by hitting .280 with 22 homers and 91 RBI. Alou had 10 hits in 20 at-bats to help the Cubs defeat the Braves in the NLDS. In the NLCS vs. the Marlins, the Cubs were leading the series 3-games-to-2 in Game 6 – and held a 3-0 advantage in the top of the eighth inning. With one on and one out, the Marlins’ Luis Castillo lifted a fly ball down the left field line. Alou appeared to be under the ball in the narrow foul territory at Wrigley Field, but a fan – later identified as Steve Bartman – reached over the railing and deflected the ball, causing Alou to angrily slam his glove against his body in frustration. Castillo ended up drawing a walk – opening the floodgates as the Marlins scored eight runs. Florida won Game 7 the next night to deny the Cubs trip to the World Series. “Poor guy,” Alou later said of Bartman. “Come to the park and all he wanted was a souvenir.” Alou had his best season with the Cubs in 2004, hitting .293 with a career-high 39 homers and 106 RBI. But Chicago finished in third in the NL Central and allowed Alou to leave as a free agent. On Jan. 5, 2005, Alou and the Giants finalized a two-year deal worth $13.25 million, reuniting Alou with his father, who was then the Giants’ manager. Alou hit .321 with 19 homers and 63 RBI in 123 games in 2005, earning his sixth-and-final All-Star Game selection. He hit .301 with 22 homers and 74 RBI in a reserve role in 2006, then signed a one-year deal with an option year with the Mets – turning down a guaranteed two-year contract with the Indians for the chance to play with his close friend Pedro Martínez. “I’ve never seen a better fastball hitter than Moises Alou,” Martínez told the New York Daily News. “I’ve seen (Gary) Sheffield. I’ve seen a lot of players. Anybody that throws a hard fastball can throw it at Moises and I’ll take my chances.” Alou slashed .341/.392/.524 in 87 games in 2007, putting together a 30-game hitting streak from Aug. 23-Sept. 26. He returned to the Mets in 2008 but appeared in only 15 games – hitting .347 – due to a torn left hamstring. After captaining the Dominican Republic in the 2009 World Baseball Classic, Alou retired to his horse farm in the Dominican. In 2010, he was the general manager of the Escogido team that won the Caribbean World Series. Alou finished his 17-year big league career – which included two seasons where he played a total of 31 games and does not include two full seasons he missed due to injury – with a .303 batting average, 332 home runs, 1,109 runs scored, 1,287 RBI, 106 steals and a .516 slugging percentage. “When I was first in the big leagues, I had all the talent but I was pretty much going through the motions blah, blah, blah,” Alou told Newsday after his retirement. “I decided I wanted to be a baseball player and I wanted to be a good one. And I played for a long time. You pretty much have to take control of yourself.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

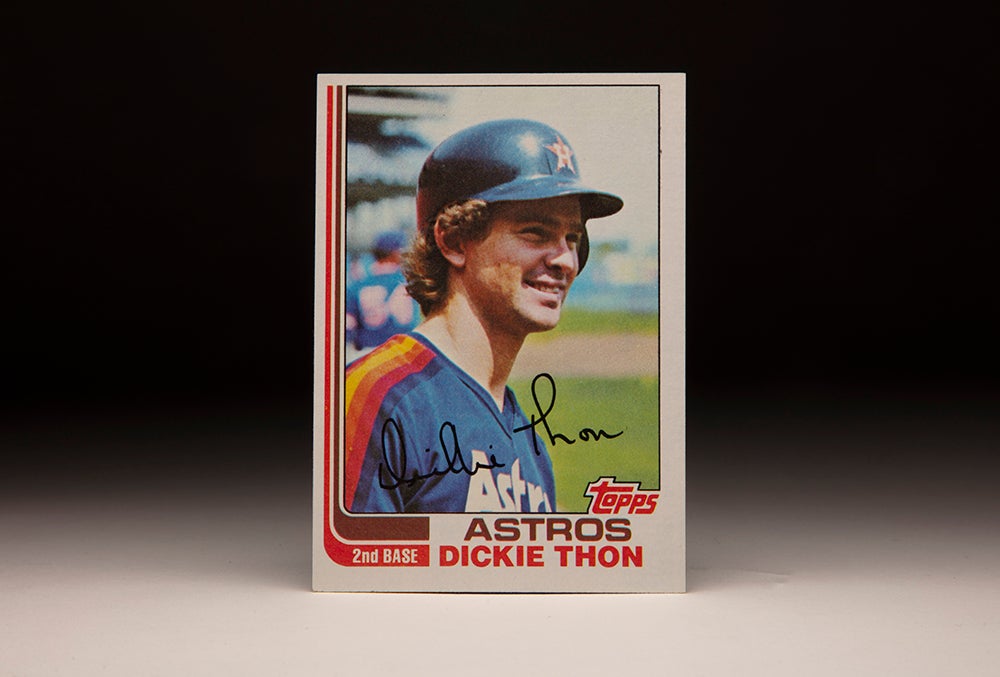

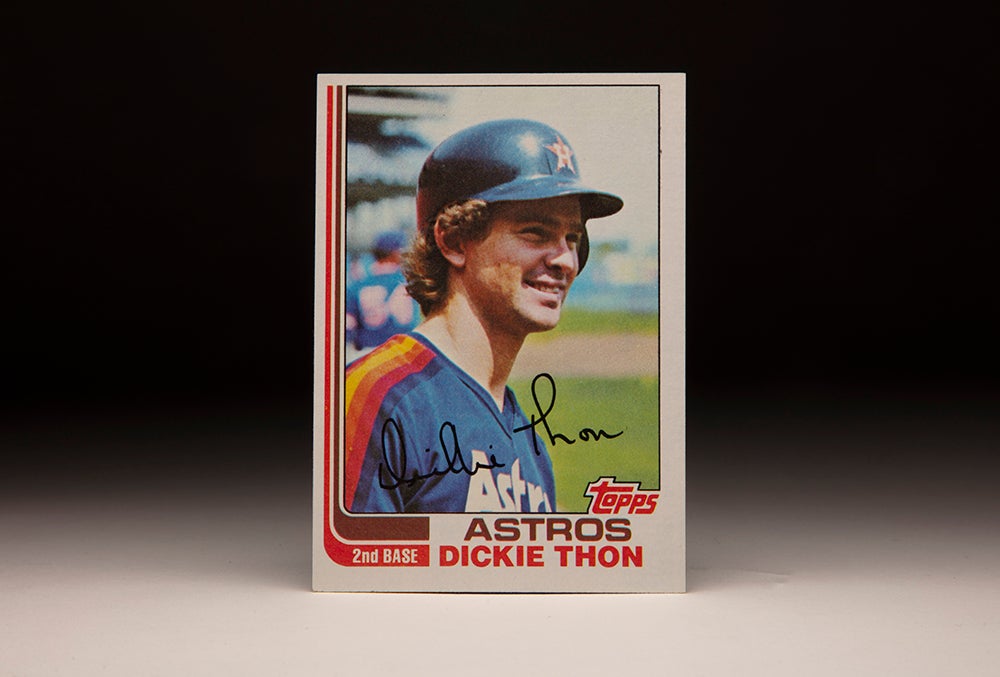

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Dickie Thon

#CardCorner: 1990 Fleer Mark Langston

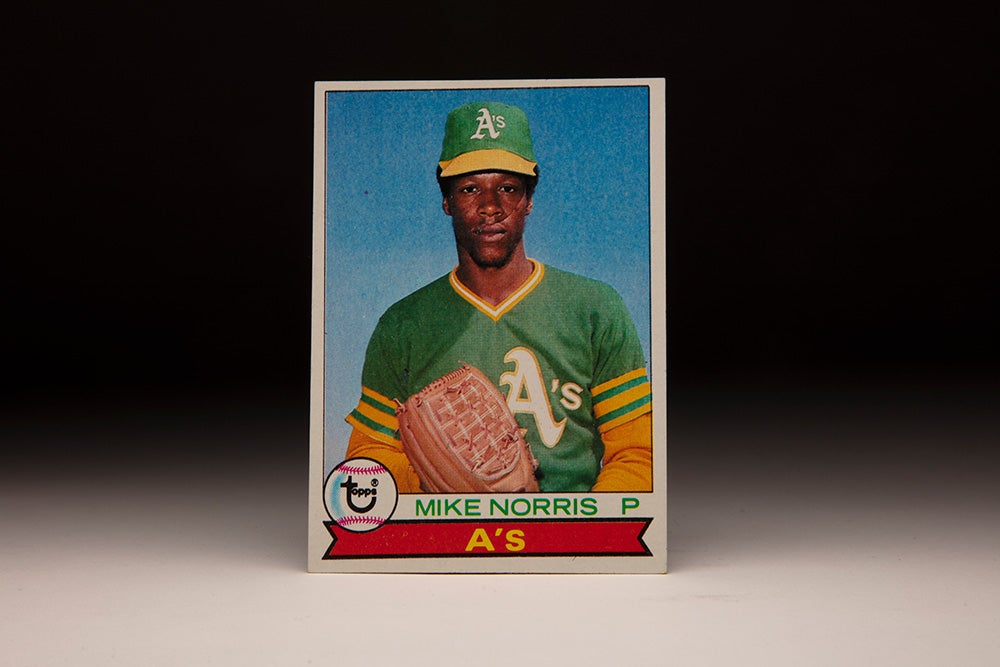

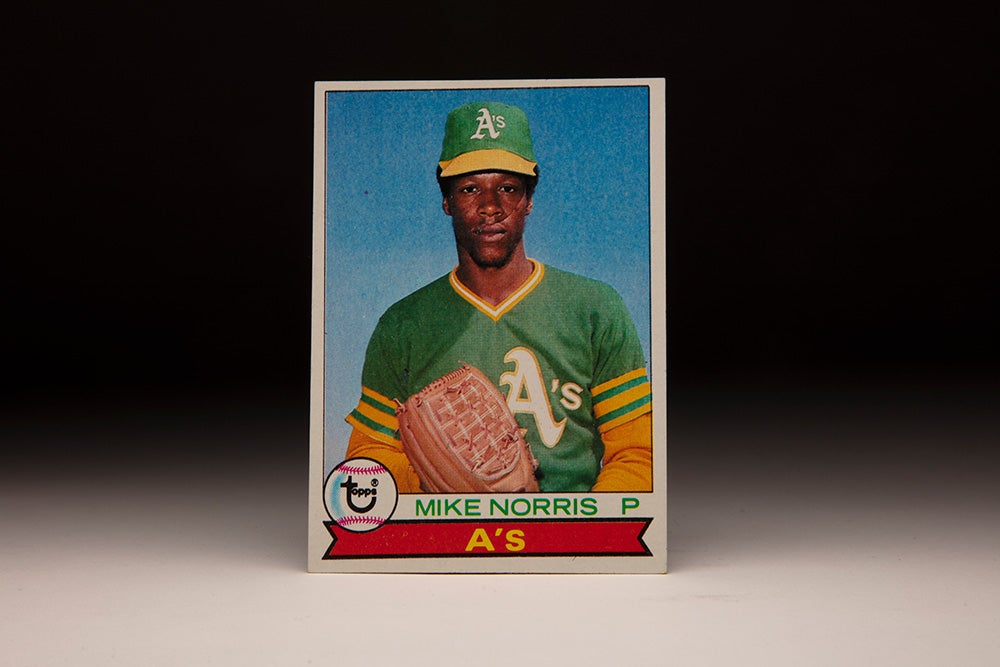

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Norris

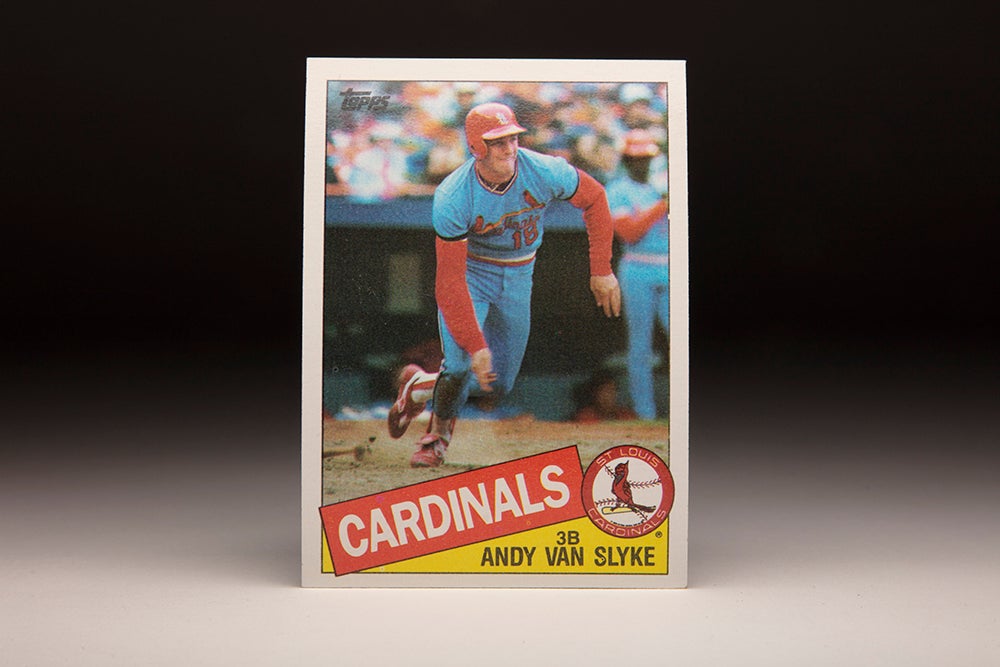

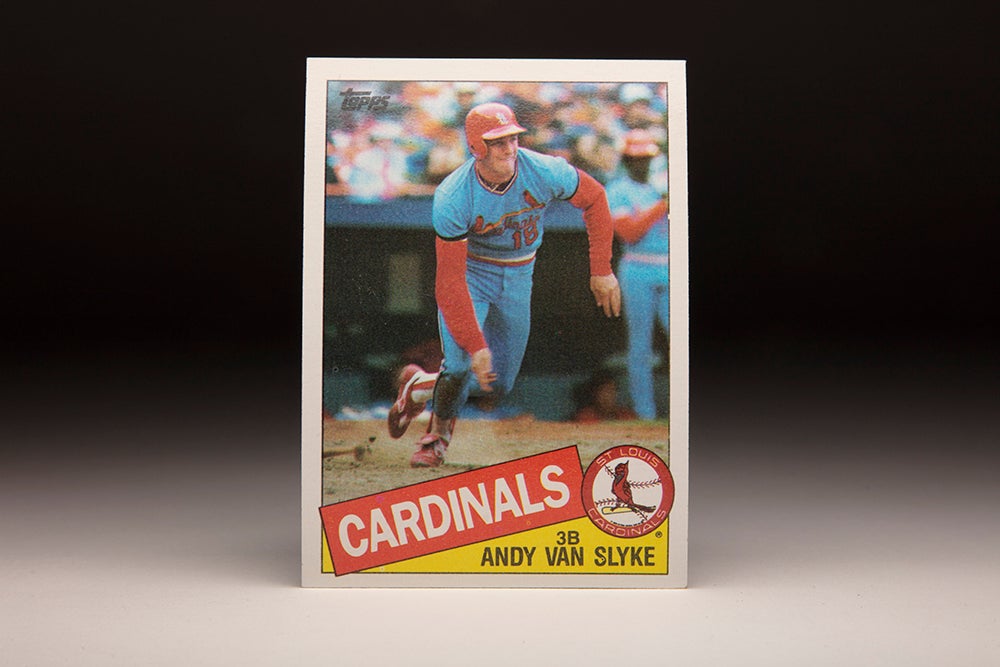

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Andy Van Slyke

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Dickie Thon

#CardCorner: 1990 Fleer Mark Langston

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Norris