- Home

- Our Stories

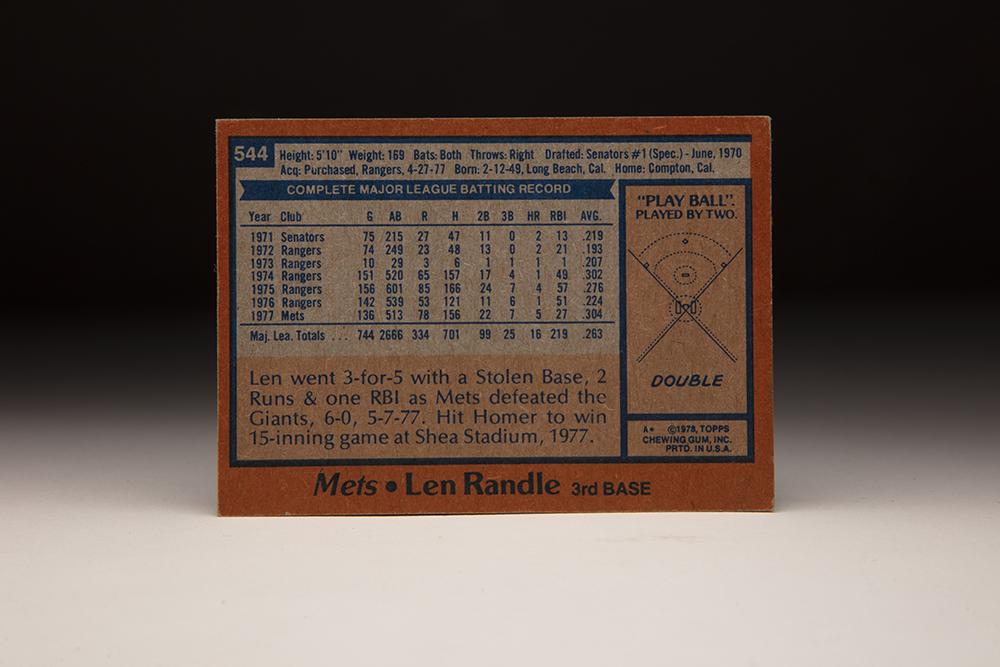

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Lenny Randle

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Lenny Randle

Lenny Randle appeared in 12 big league seasons, coming to the plate at least 500 times in half of those campaigns.

He never made an All-Star team, never led the league in any major category and never appeared in the postseason.

But Lenny Randle may have seen more memorable moments than any other player of his era.

Born Feb. 12, 1949, in Long Beach, Calif., Randle grew up in Compton in South Central Los Angeles as one of eight children. His father, Isaac, was a boilermaker who donated one of his kidneys to help save one of the younger Randle children, Herman.

“My father was an amazing man; my brother showed me courage I had never seen before,” Randle told the Associated Press. “I decided that they would be examples of my drive and sacrifice.”

Starring in both baseball and football at Centennial High School, Randle was selected in the 10th round of the 1967 MLB Draft by the Cardinals but chose to enroll at Arizona State. He played both baseball and football for the Sun Devils, moving into the starting lineup on Bobby Winkles’ team as a freshman in 1968 and helping ASU win its third national title in five years in 1969.

That same year, Randle excelled for the football team – scoring twice in one game against San Jose State, including a 76-yard punt return for a touchdown. He eventually earned a degree in political science from ASU.

Following the 1970 baseball season, Randle was selected 10th overall in the MLB Draft by the Senators. He immediately reported to Triple-A Denver, where he hit. 208 in 46 games.

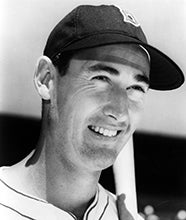

In 1971, Randle returned to Denver and was hitting .288 through 48 games when the Senators called him up in June. He quickly became a favorite of manager Ted Williams but struggled at the plate, hitting .219 in regular action at second base.

In 1972, the Senators relocated to Dallas/Fort Worth to become the Texas Rangers. In the Rangers’ first-ever game on April 15 against the Angels, Randle became the first batter in team history when he led off and struck out against Andy Messersmith.

Randle – along with virtually every other Rangers batter – struggled mightily in 1972. He was sent back to Denver in July after hitting .193 over 74 games. He finished the season with the Bears, hitting .261 in 41 games.

Then in 1973, Randle spent almost the entire season with Triple-A Spokane, hitting .283 with 118 runs scored, 81 walks and 39 stolen bases in 140 games. He appeared in 10 games in September with the Rangers before playing winter ball in the Dominican Republic.

In 1974, a relaxed Randle reported to Spring Training with a new outlook on life.

“I try to use the power of the subconscious mind and apply it to my total awareness,” Randle told the Fort Lauderdale News, ascribing his growth in part to listening to songs by ex-Beatles guitarist George Harrison. “I’m much more relaxed than I’ve ever been. There’s no need for any tension. The mind is capable of overcoming that.”

Meanwhile, new Rangers manager Billy Martin liked what he saw out of his unique infielder.

“He’s an exciting ballplayer,” Martin said. “He makes things happen.”

Randle started the season as utility player but moved into the lineup as the third baseman in mid-April and played either second or third for most of the rest of the season. He finished with a .302 batting average and 26 steals over 151 games, finishing 21st in the American League Most Valuable Player voting as the Rangers – who lost 105 times in 1973 – won 84 games.

One of those wins came on a forfeit against the Indians on June 4 – a game forever remembered as Ten-Cent Beer Night at Cleveland Stadium. Randle went 0-for-4 with a walk and made the second out of the top of the ninth, flying to left field against Cleveland’s Milt Wilcox. In the bottom of the ninth, with Texas leading 5-3, the Indians tied the game on a John Lowenstein sacrifice fly – and fans quickly got out of control. The umpires declared a forfeit in favor of the Rangers.

In 1975, Randle reprised his utility role and hit .276 with 85 runs scored and 57 RBI in 156 games, spending most of his time at second base or center field. But Martin was fired in July and replaced by Frank Lucchesi as Texas fell to 79-83. It would be a managerial choice that would impact Randle’s career in ways he could not have anticipated.

Playing mostly at second base in 1976, Randle slumped to a .224 batting average but still drove in 51 runs and stole 30 bases. But in Spring Training of 1977, Randle’s career took an unexpected turn when Lucchesi informed him on March 28, prior to an exhibition game against the Twins in Orlando, Fla., that rookie Bump Wills would be the team’s starting second baseman.

Words were exchanged, and Randle punched Lucchesi in the face multiple times – breaking his jaw. Lucchesi spent five days in the hospital. Randle was suspended for 30 days, fined $10,000 and then traded to the Mets on April 26 in exchange for Rick Auerbach. Randle later pleaded no contest to battery charges and paid a $1,000 fine. Lucchesi sued Randle in September and asked a civil court for $200,000 in damages. Randle and Lucchesi eventually settled out of court.

“I pray for the man, and I bless him,” Randle told the Arizona Republic about Lucchesi in 1980. “We’ve both suffered. I hope he can understand that.”

Amidst all this turmoil, Randle had an exceptional season on the field. He appeared in 136 games for the Mets, hitting .304 with 78 runs scored, 65 walks and 33 steals. The Mets awarded Randle a reported $8,000 raise in his contract during the 1977 season – but Randle felt the Mets had promised him more and “retired” at the start of Spring Training in 1978, only to return to the team 48 hours later.

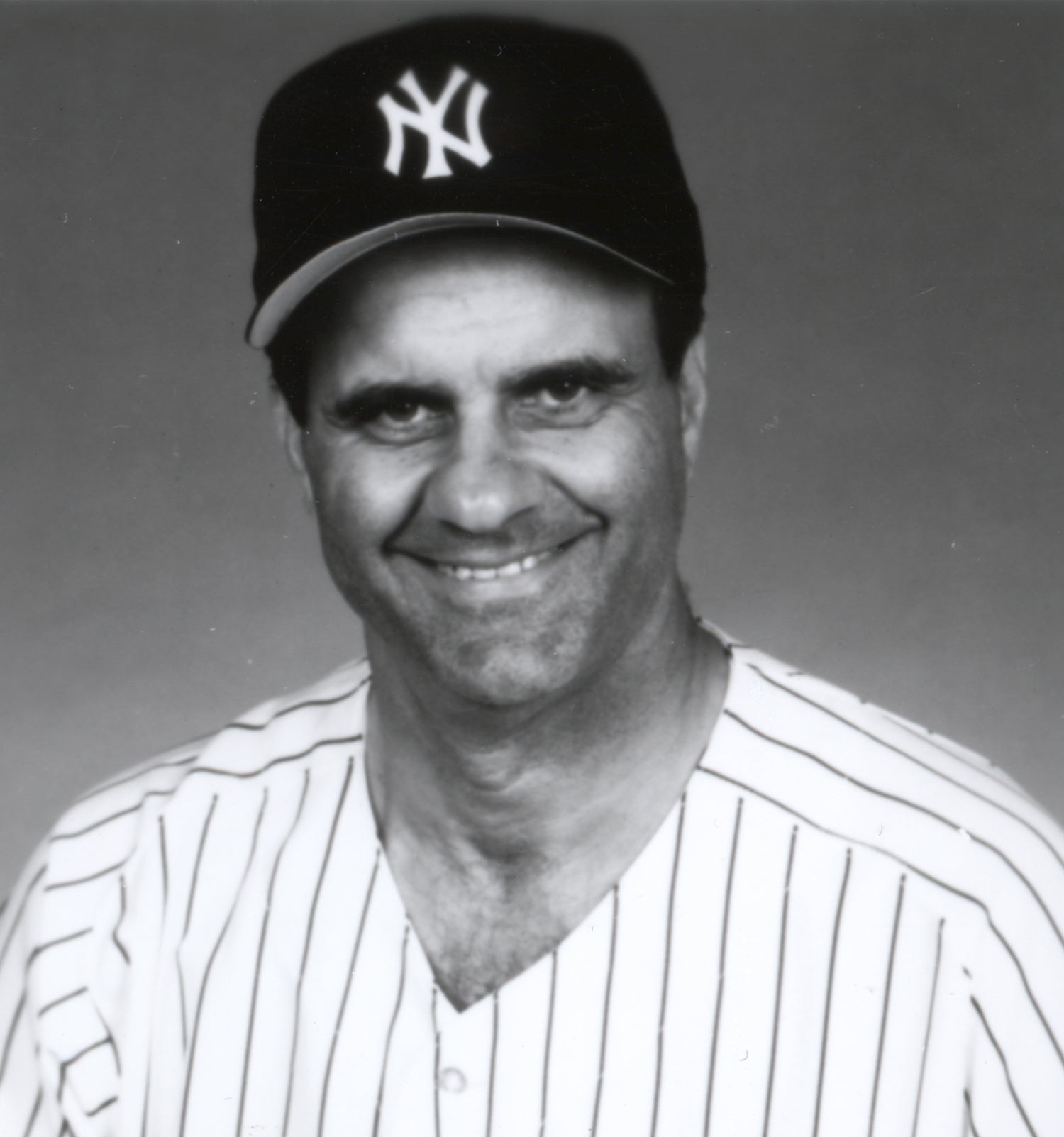

“Certain promises were made to me when I signed,” Randle told the New York Daily News. “Those promises were not kept. I came back for the fans and for (Mets manager) Joe Torre. That doesn’t put bread on my table but it does give me peace of mind.”

Randle was unable to recapture his 1977 form, however. As the Mets’ everyday third baseman again in 1978, Randle hit .233 over 132 games and stole just 14 bases.

On March 29, 1979, the Mets released Randle, who had three years remaining on a contract that paid him $100,000 per season but that was mostly unguaranteed. By waiving Randle, the Mets were only on the hook for one-sixth of his 1979 salary and no money afterward.

“He was stunned, really shocked,” Mets manager Joe Torre told the Daily News of Randle’s reaction. “It really hit him hard because it never entered his mind he might be cut.”

Thus started a saga that saw Randle become a member of the eventual 1979 World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates, even though he never played a game for Pittsburgh. On May 16, he signed with the San Francisco Giants, who sent him to Triple-A Phoenix. After 42 games in the Pacific Coast League, Randle was traded to Pittsburgh along with Bill Madlock and Dave Roberts in exchange for Fred Breining, Al Holland and Ed Whitson on June 28. The Pirates quickly assigned him to their PCL outpost in Portland, then sold his contract to the Yankees on Aug. 3.

Randle debuted in New York a day later and played 20 games for the Yankees that year, hitting .179 off the bench. Following the season, Randle became a free agent. He signed with the Mariners as a non-roster player in February of 1980 but was sold to the Cubs on April 1.

Nine days later, Randle was playing second base and batting leadoff for Chicago on Opening Day. He hit .276 that season, scoring 67 runs in 130 games while spending most of his time at third base. He became a free agent once again following the season – and once again he signed with the Mariners.

Reprising his role as a utility player – appearing at third base, second base, shortstop and all three outfield spots at various times throughout the shortened 1981 season – Randle already had his eyes set on his next career.

“I want to be a stand-up comedian,” Randle told the Associated Press. “I like seeing people smile. Humor is something that’s free.”

Days after that interview appeared in papers throughout the country, Randle made baseball fans around the world grin. On May 27 in the Kingdome, the Royals’ Amos Otis chopped a ball down the third base line. Neither Randle, playing third, nor Seattle pitcher Larry Andersen would have had a chance to throw Otis out. So Randle dropped to the turf and blew the ball – now rolling toward the bag in fair territory – foul.

Andersen scooped up the ball in foul territory, and home plate umpire Larry McCoy initially ruled the ball was foul. But after a discussion, Otis was awarded a base hit. The video of Randle steering the ball into foul territory with his breath became one of the most replayed moments of the season – and will live forever on blooper reels.

“I yelled at (the ball),” Randle told the News Tribune of Tacoma, Wash. “I said: ‘Please go foul! Please go foul!’ I was yelling at it, and it worked.”

But the umpires had the last word.

“None of us had ever seen anything like it,” said crew chief Dave Phillips. “We had to talk about it for a minute. I think Lenny did it to be funny, and it was funny. But you can’t alter the course of the ball.”

Randle would appear in 82 games with the Mariners that season, hitting .231. After playing in 30 games in 1982 – mostly as a pinch-runner – Seattle released Randle, ending his big league career.

But Randle wasn’t through. In 1983, he went to Italy to participate in that country’s pro baseball league – hitting. 477 over the 50-game season to win the batting title. In October of 1983, he was featured on the highly-rated CBS show “60 Minutes” for his work with Italian baseball.

Fluent in four languages (English, French, Spanish and Italian) and filled with an entrepreneurial spirit, Randle dabbled in promotions, music, comedy, athletic shoes, agent’s work and charity benefits.

“I was getting bored with baseball (in the United States),” Randle told the Boston Globe of his decision to play in Italy. “It wasn’t something I had to do.”

Over 12 years in the big leagues, Randle stayed busy to the tune of a .257 batting average, 1,016 hits, 488 runs scored and 156 stolen bases.

Few players of his time were at the center of attention as frequently as Lenny Randle.

“I like to have something going to keep me busy,” Brown told the Globe. “It’s not an ego thing. It’s just fun.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

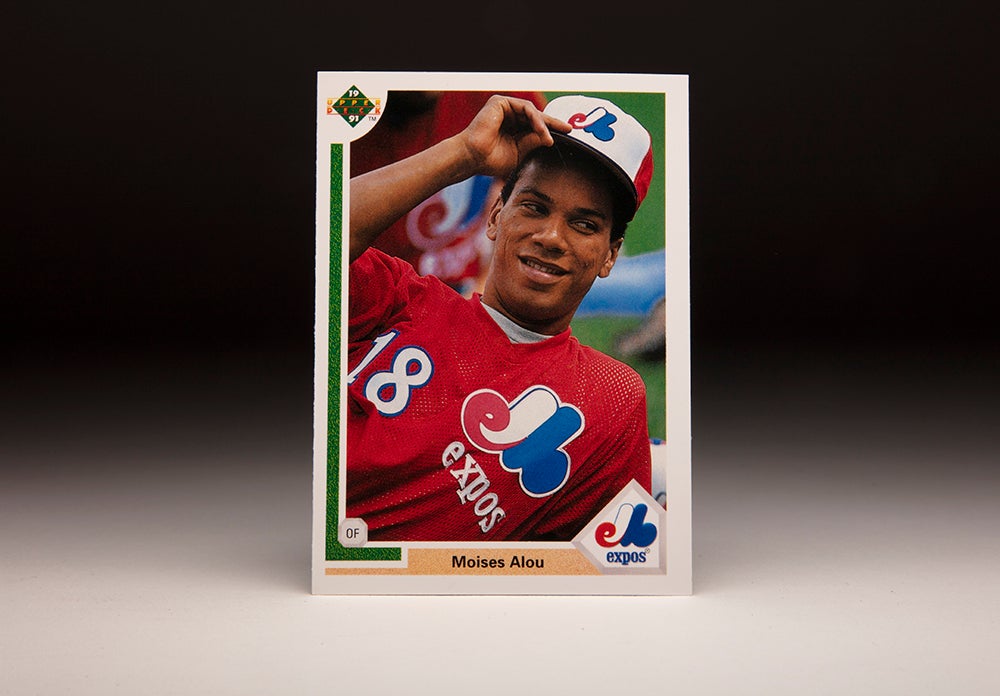

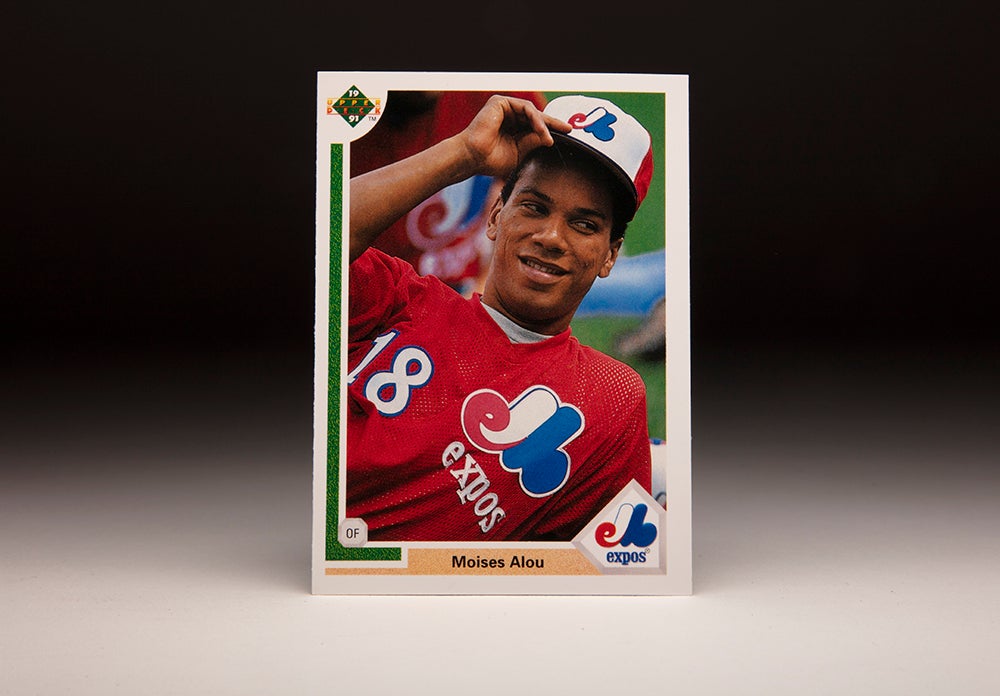

#CardCorner: 1991 Upper Deck Moises Alou

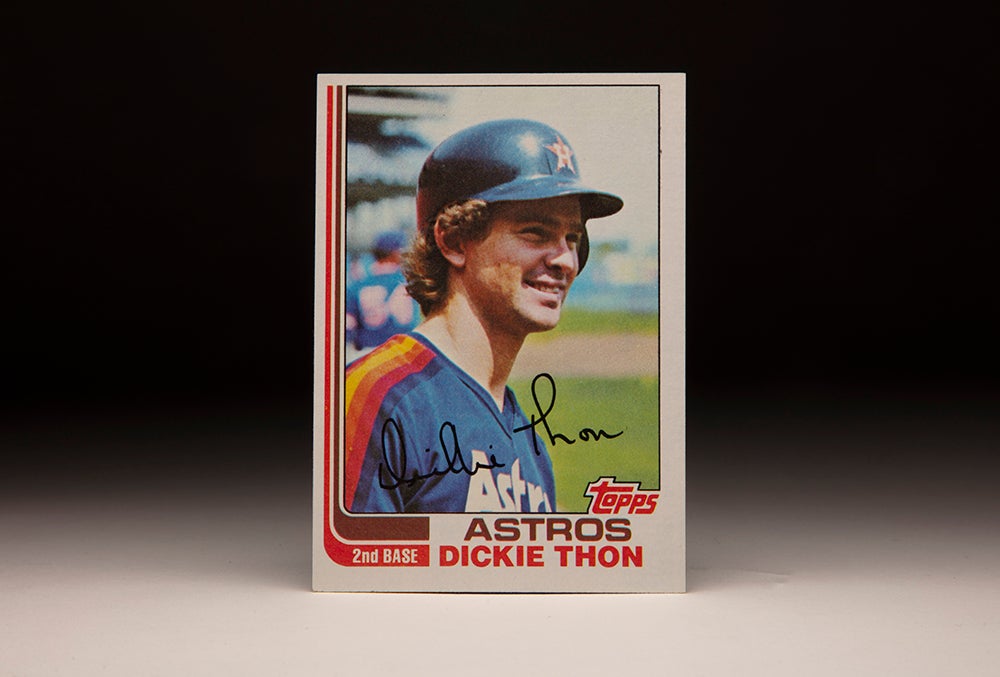

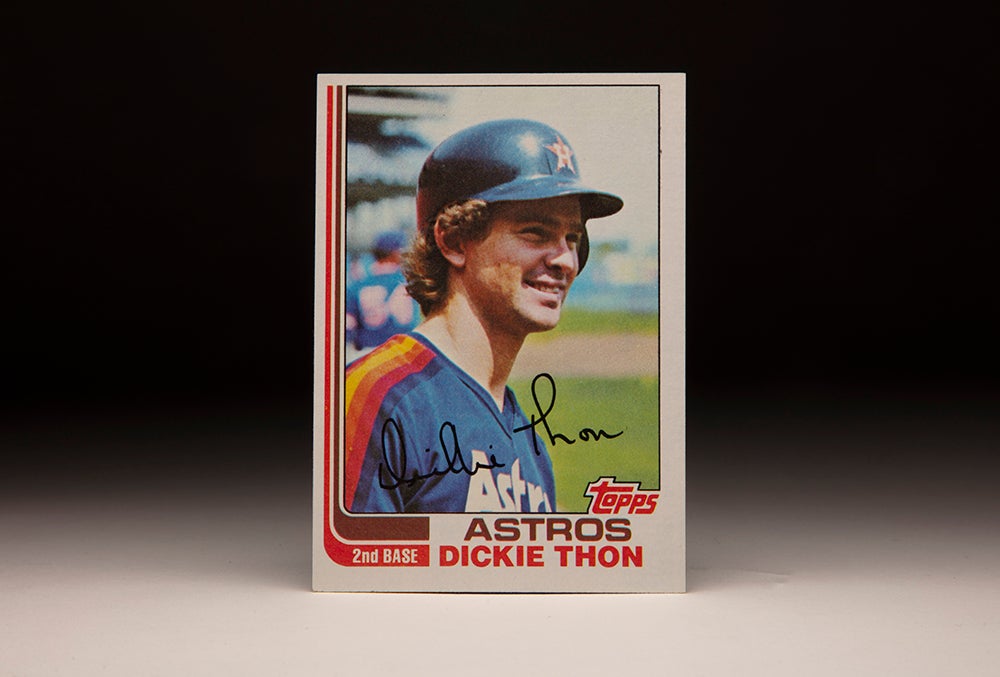

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Dickie Thon

#CardCorner: 1990 Fleer Mark Langston

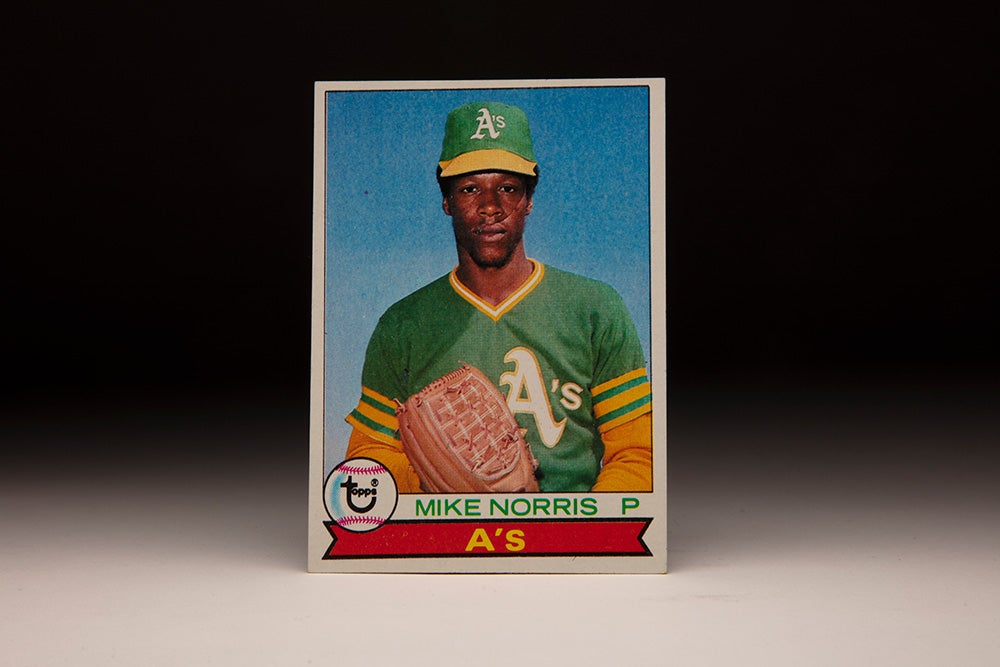

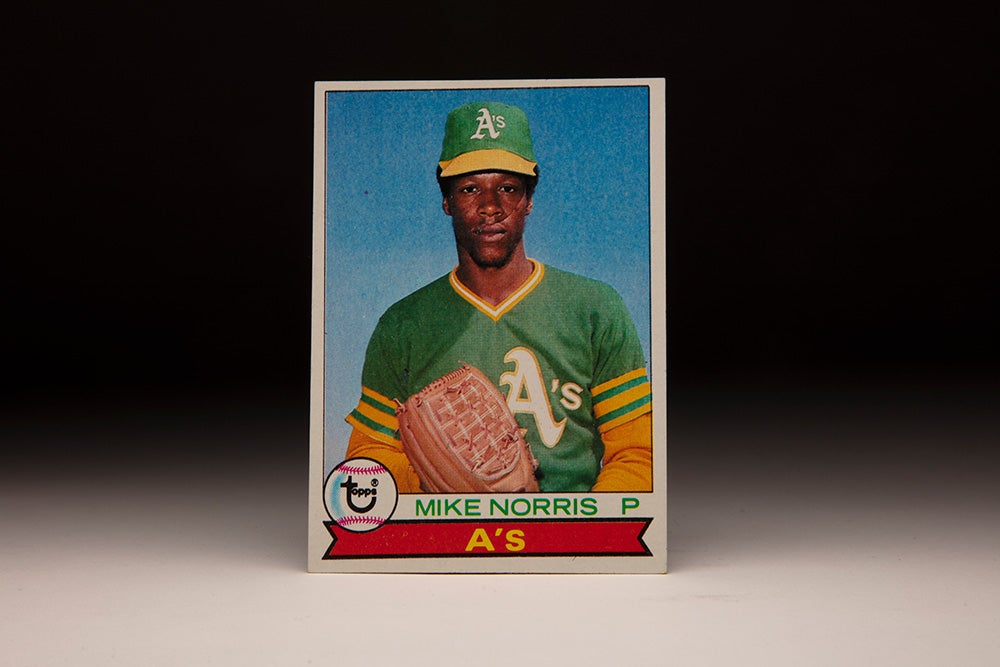

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Norris

#CardCorner: 1991 Upper Deck Moises Alou

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Dickie Thon

#CardCorner: 1990 Fleer Mark Langston