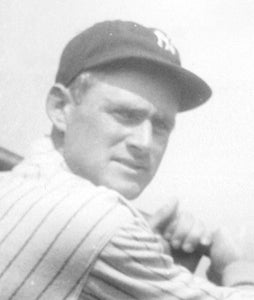

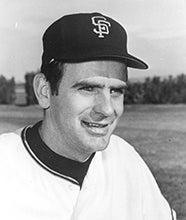

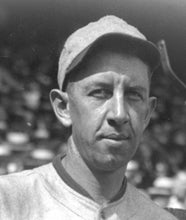

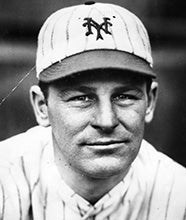

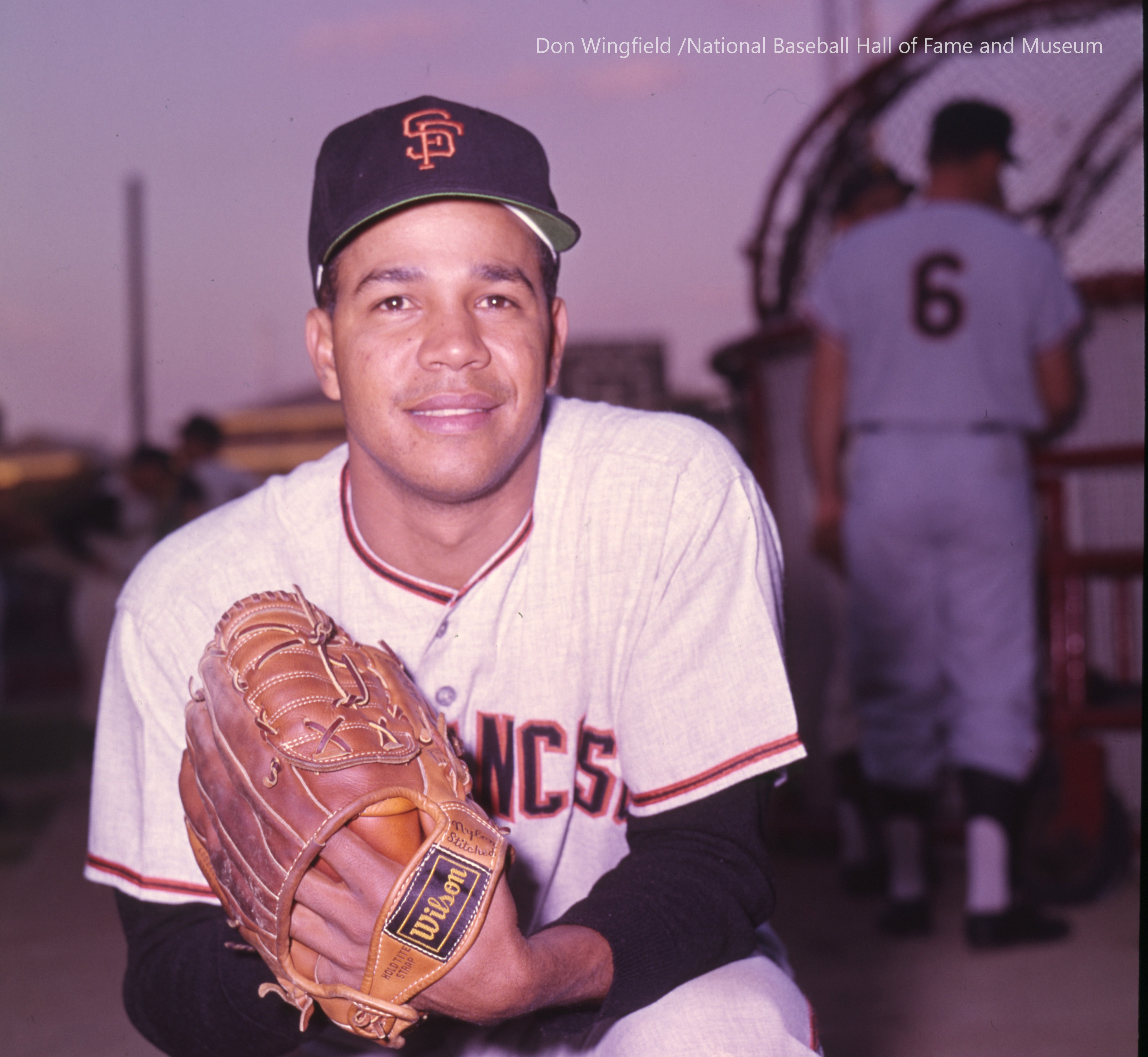

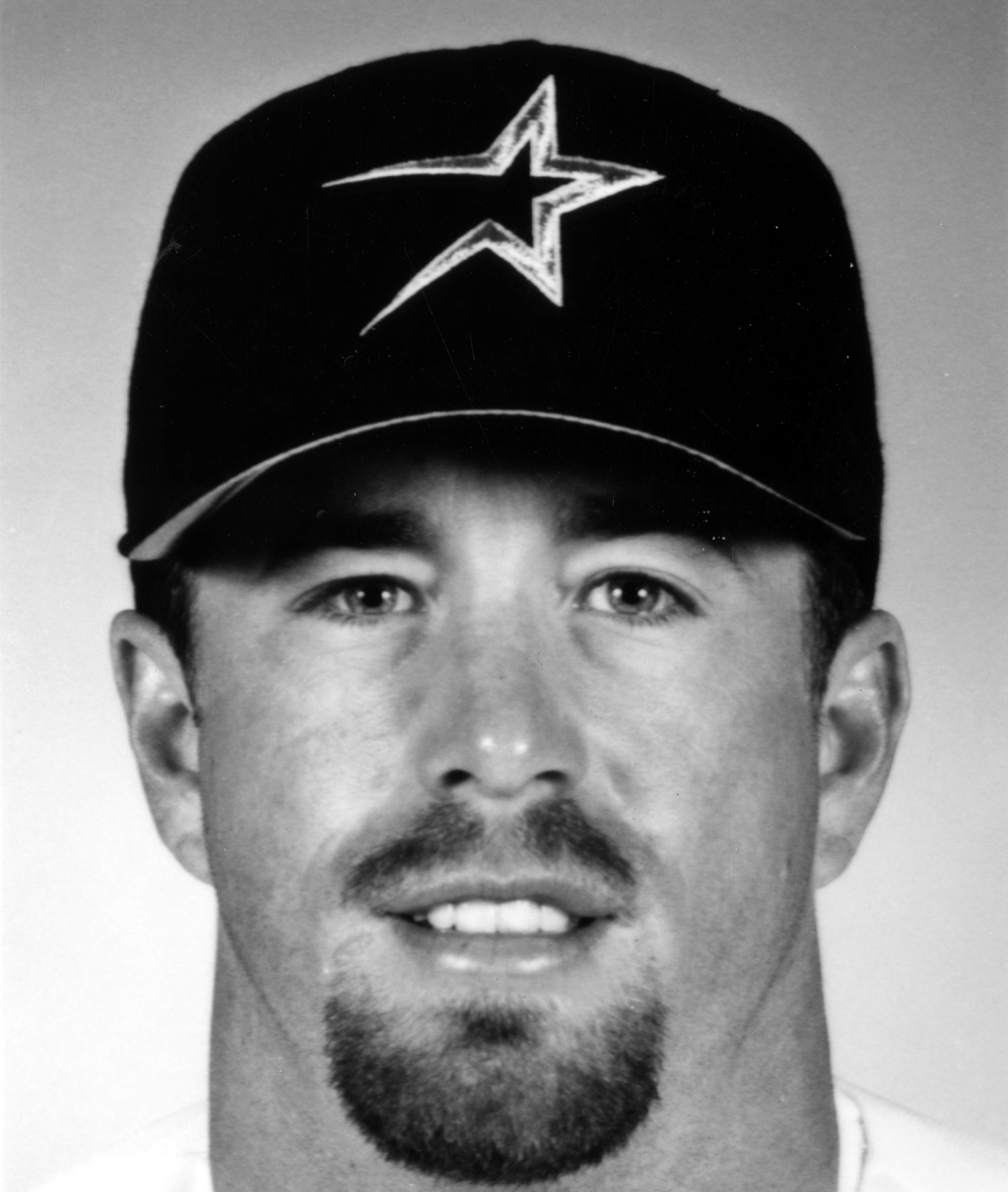

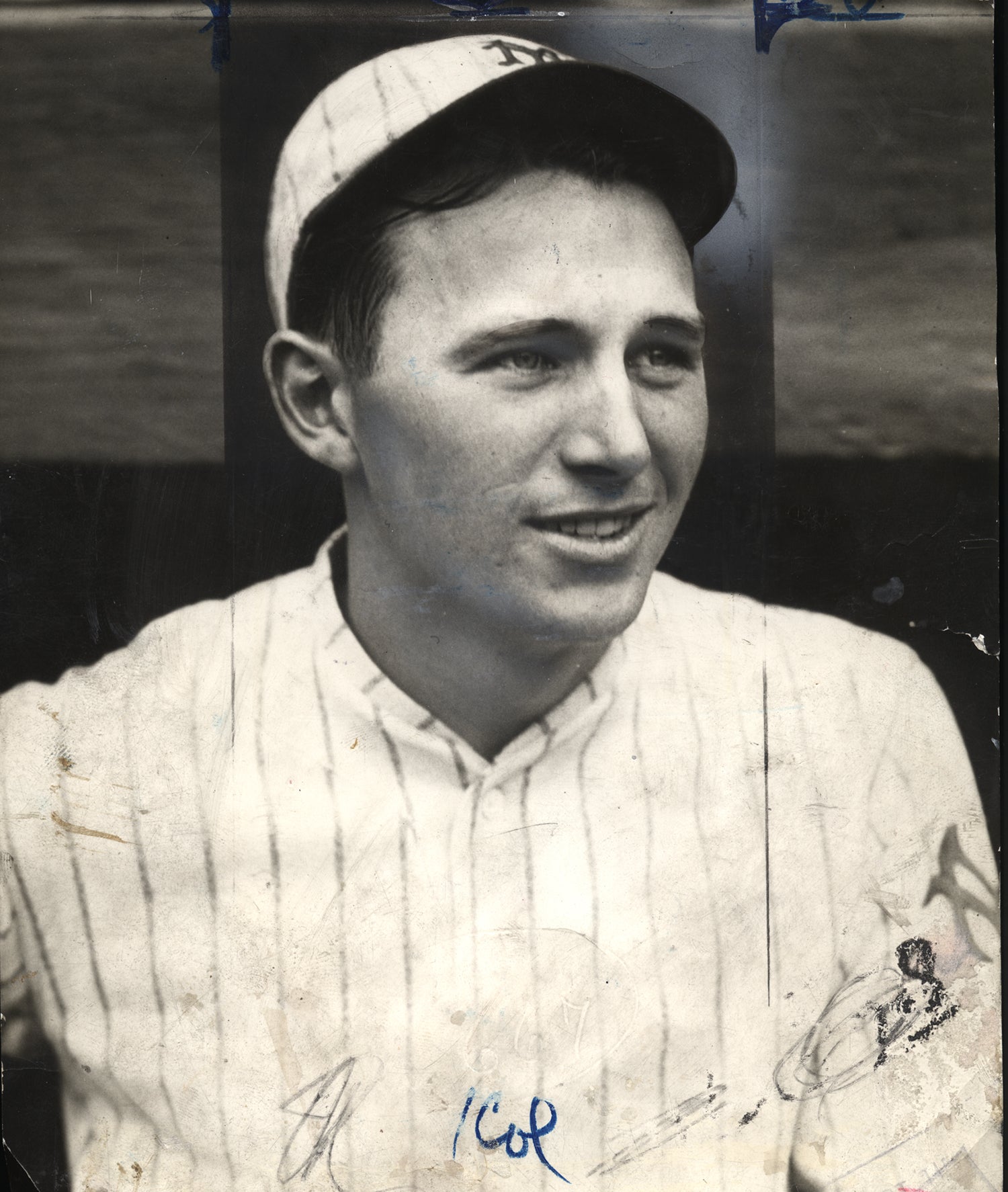

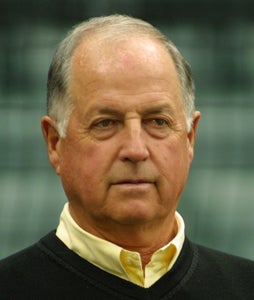

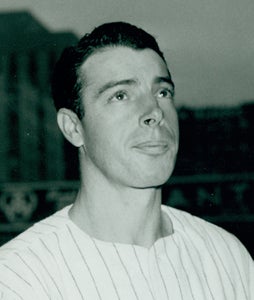

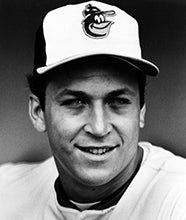

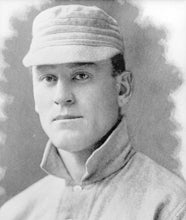

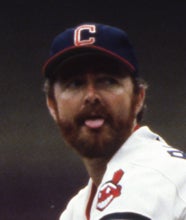

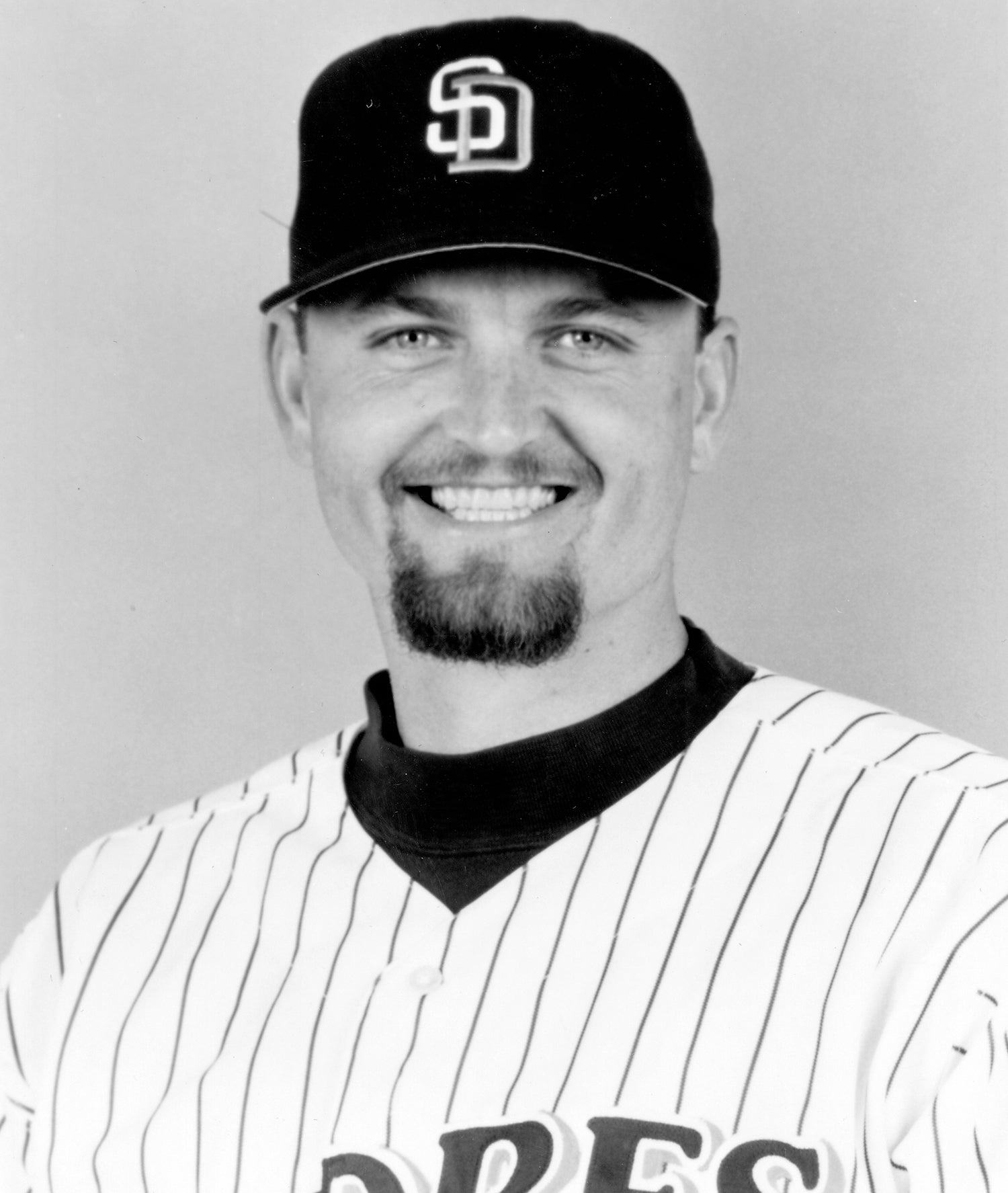

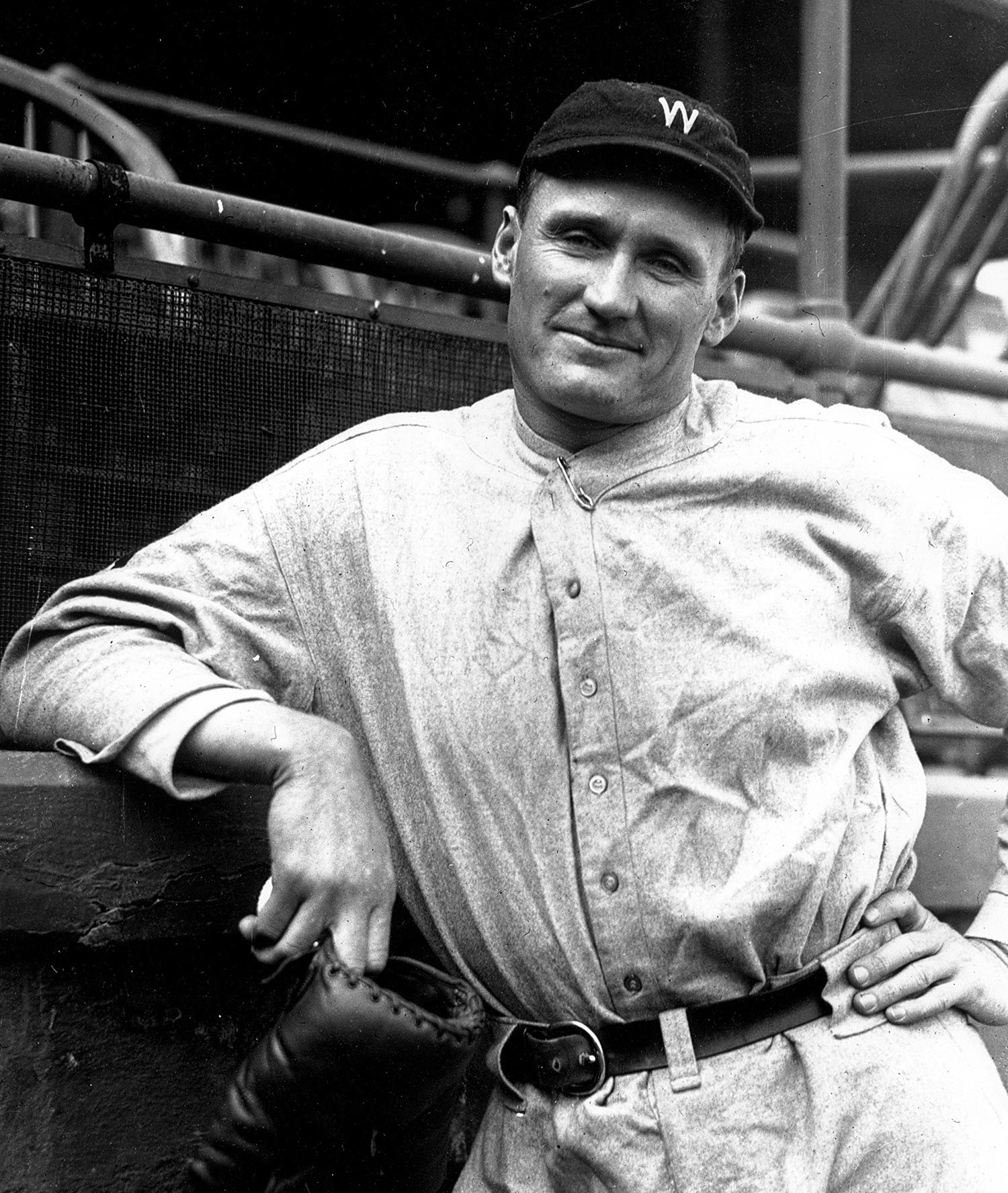

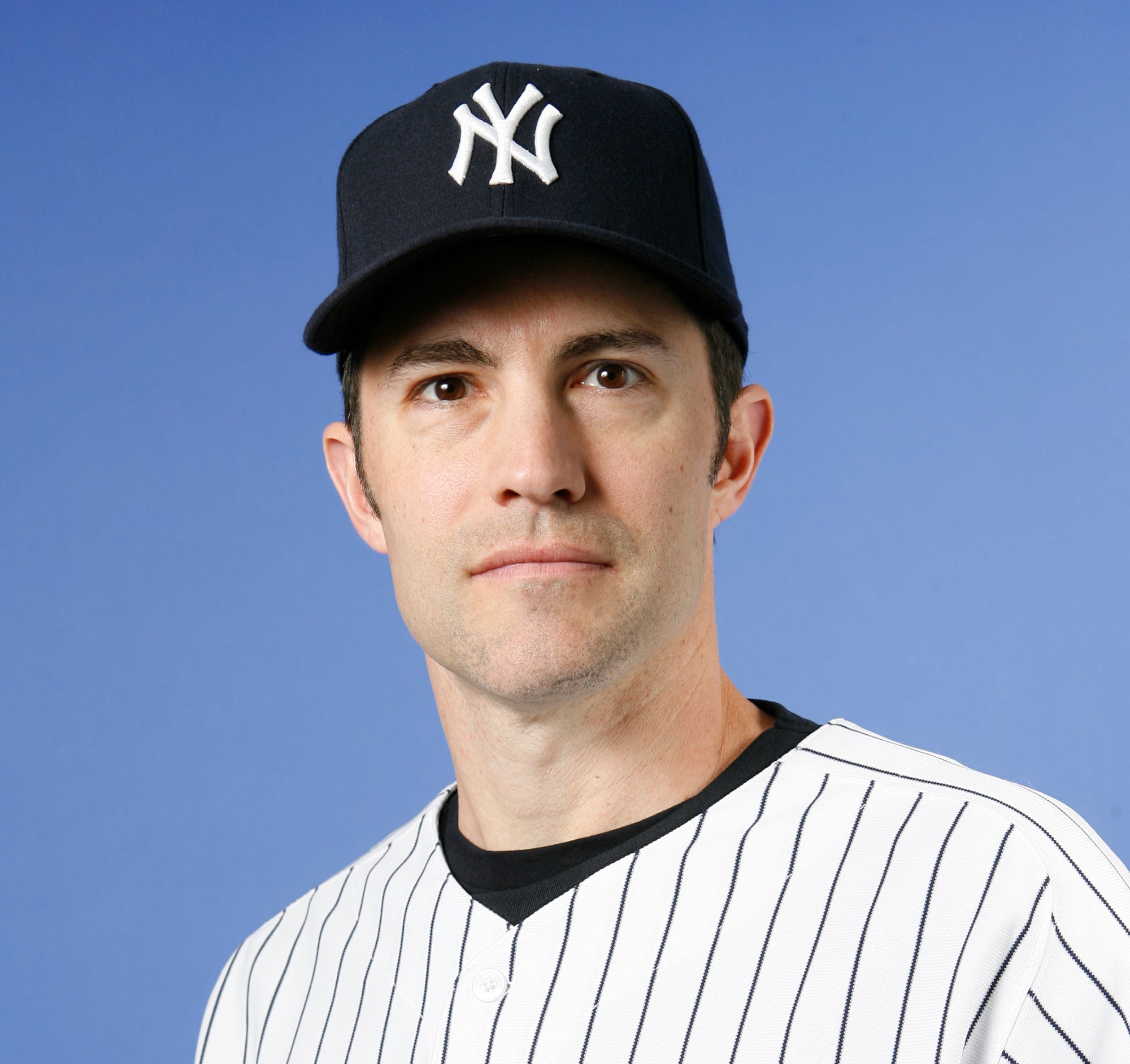

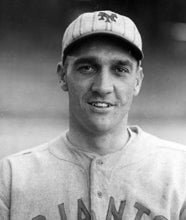

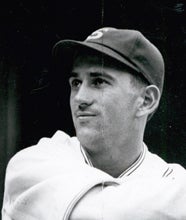

Roy Halladay went from near the top of the baseball world to the minors and back again during his pro career.

He will never leave its peak, however, now that he belongs to Cooperstown.

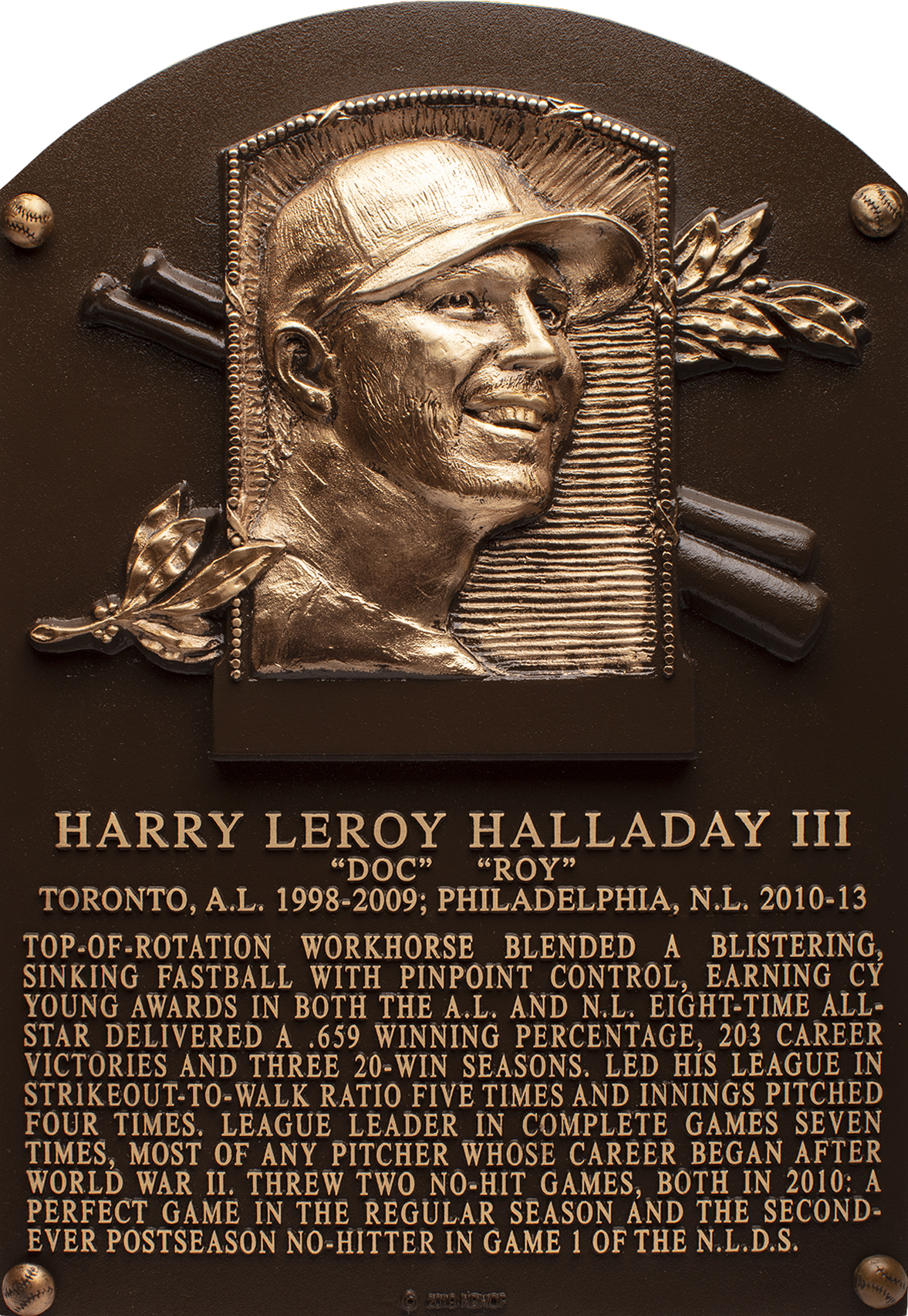

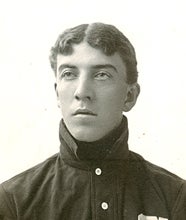

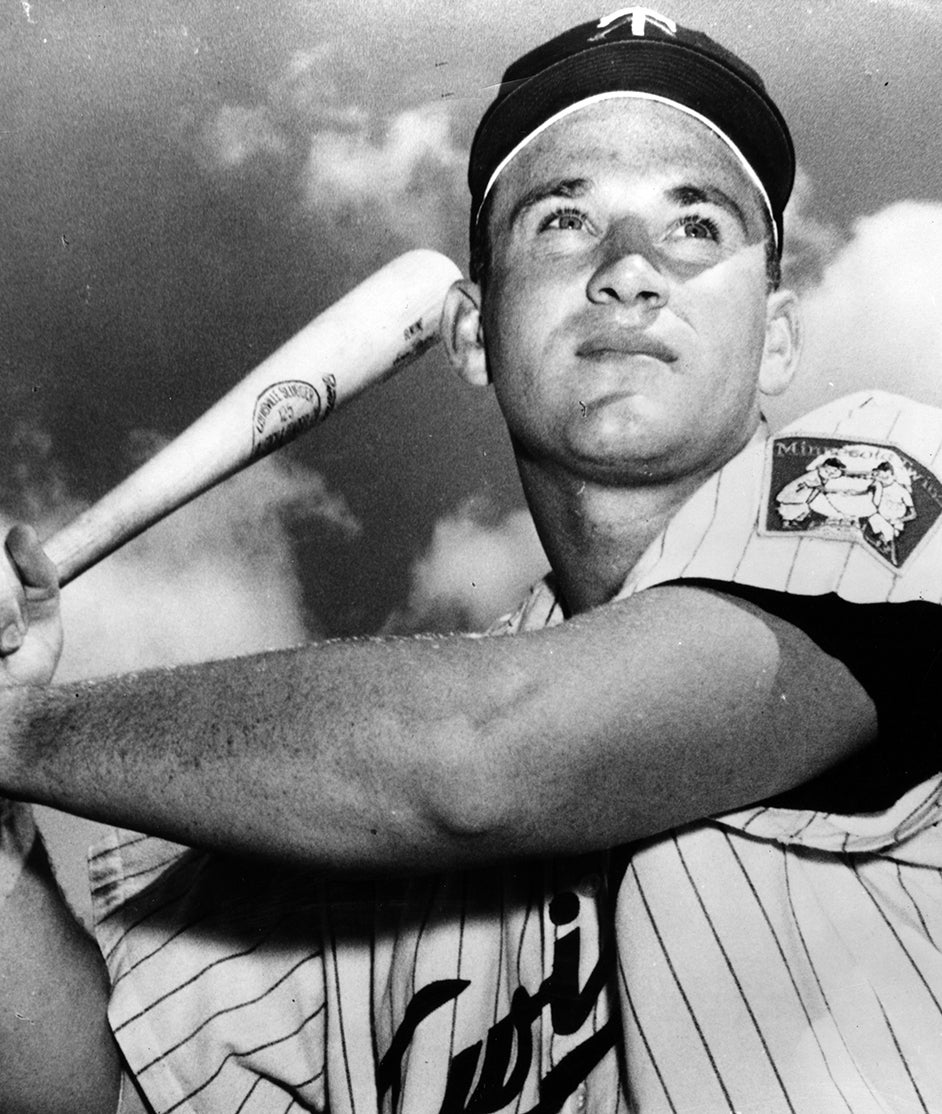

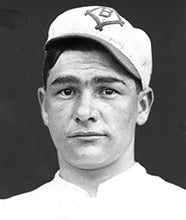

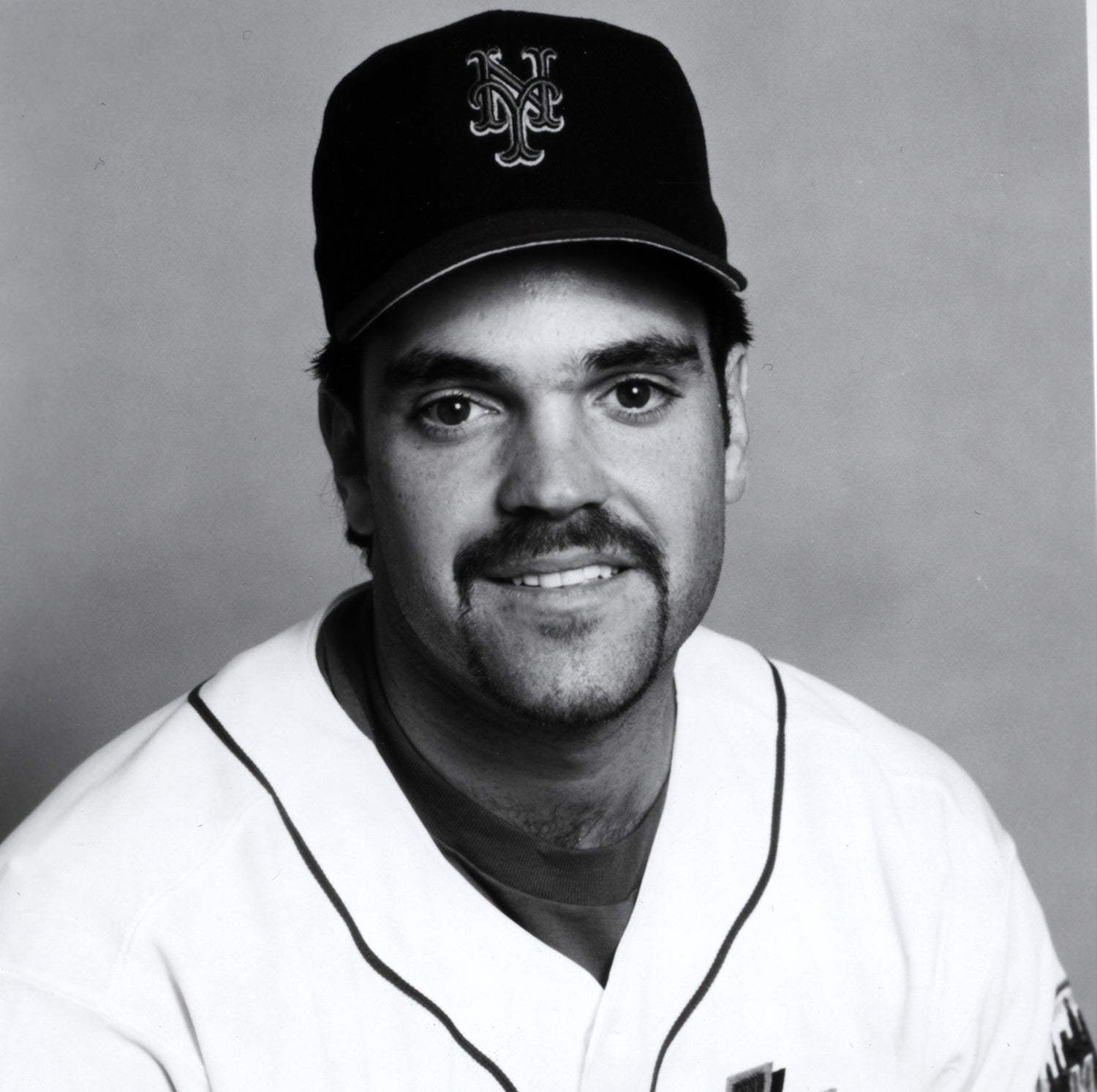

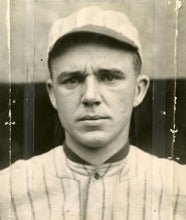

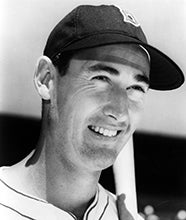

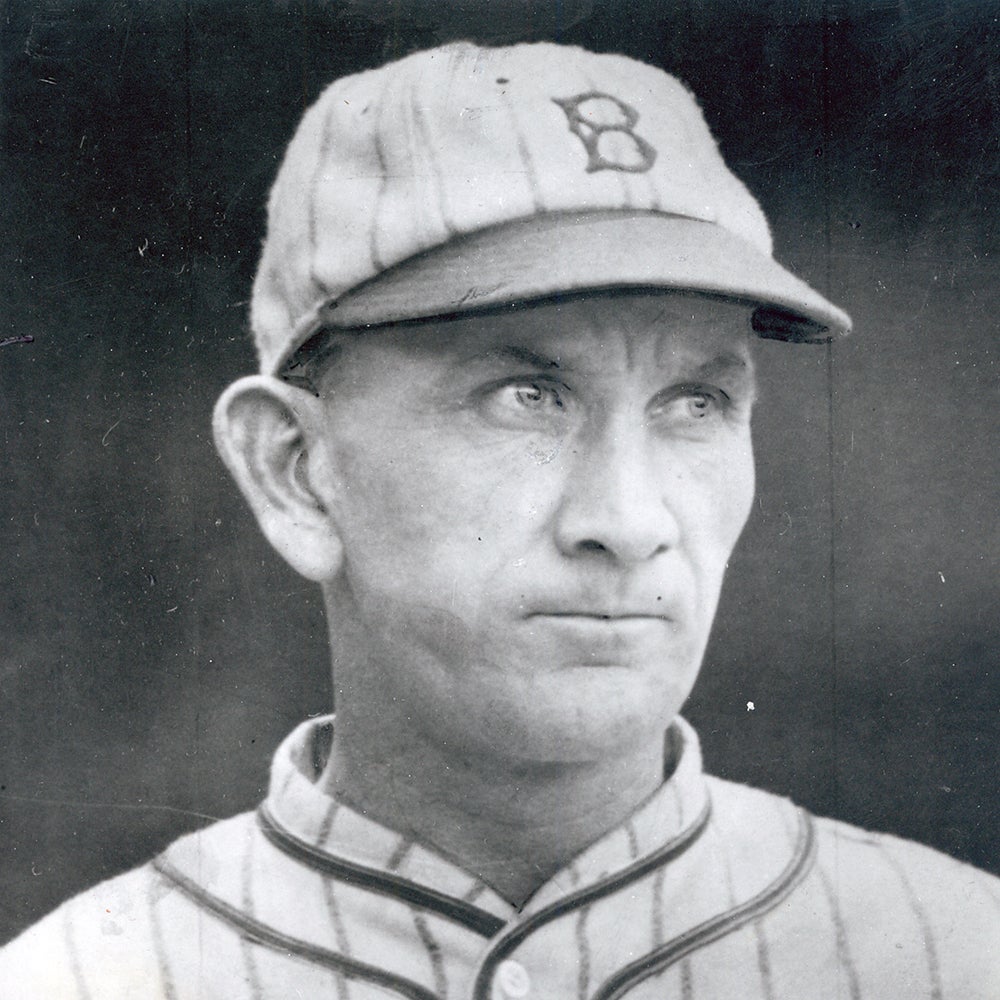

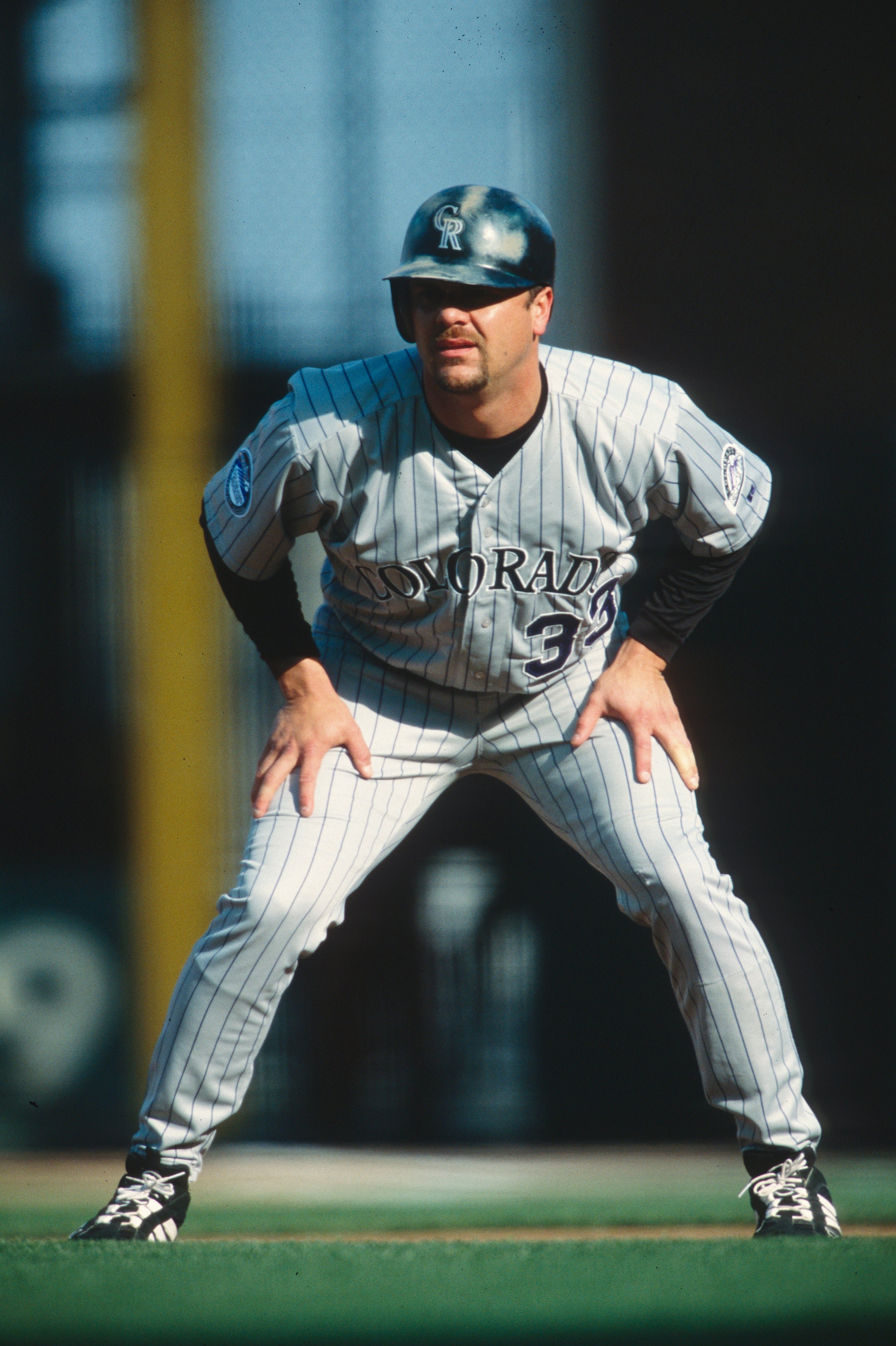

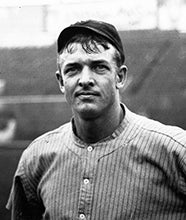

Halladay was born Harry Leroy Halladay on May 14, 1977, in Denver. He grew into a 6-foot-6, 225-pound frame perfectly suited for delivering a baseball at more than 90 miles per hour. Accordingly, the Toronto Blue Jays took Halladay – fresh off his senior season at Arvada West (Colo.) High School with the 17th overall pick in the 1995 MLB Draft.

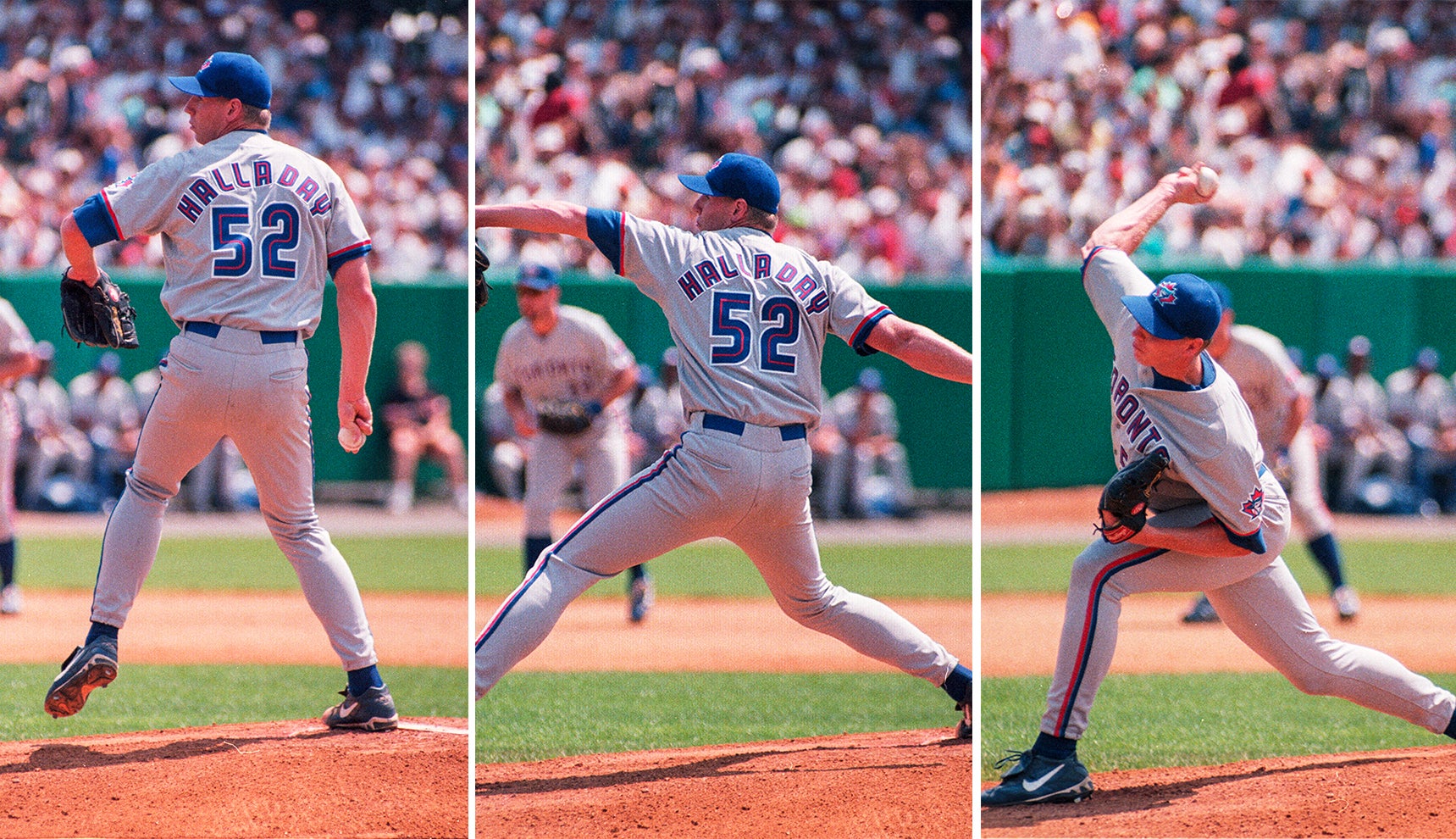

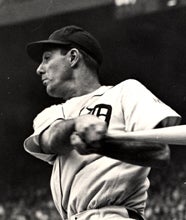

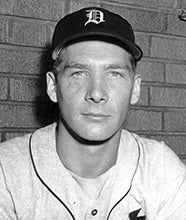

Halladay quickly advanced in the minor leagues, finding himself with Triple-A Syracuse by the end of the 1997 season. The next year, Halladay debuted with the Blue Jays as a late-season call-up. In his second start, on Sept. 27, Halladay was within one out of a no-hitter when the Tigers’ Bobby Higginson smacked a home run with two gone in the ninth.

“In some ways, it was almost an unfortunate thing that happened,” Blue Jays general manager Gord Ash told the Syracuse Post-Standard in Spring Training of 1999. “It was great to watch it and see it unfold, but at the same time, you don’t want a young pitcher like that pegged, every time he goes out there, as the guy who almost threw the no-hitter.”

Halladay was penciled into the Blue Jays rotation in 1999 but started slowly in Spring Training and began the year in the bullpen, eventually posting an 8-7 record with a 3.92 ERA. The next season, Halladay struggled to a 4-7 record with a 10.64 ERA in 19 appearances.

In late Spring Training of 2001, with Halladay still trying to find his groove, the Blue Jays sent him to the minors. Not just Triple-A, but all the way to Class A Dunedin.

“It was like a nightmare, the worst thing that could possibly happen,” Halladay told the Toronto Star in 2003. “There’s nothing you can do to feel better.”

“I told him,” Ash said, “’We need to start all over again.’”

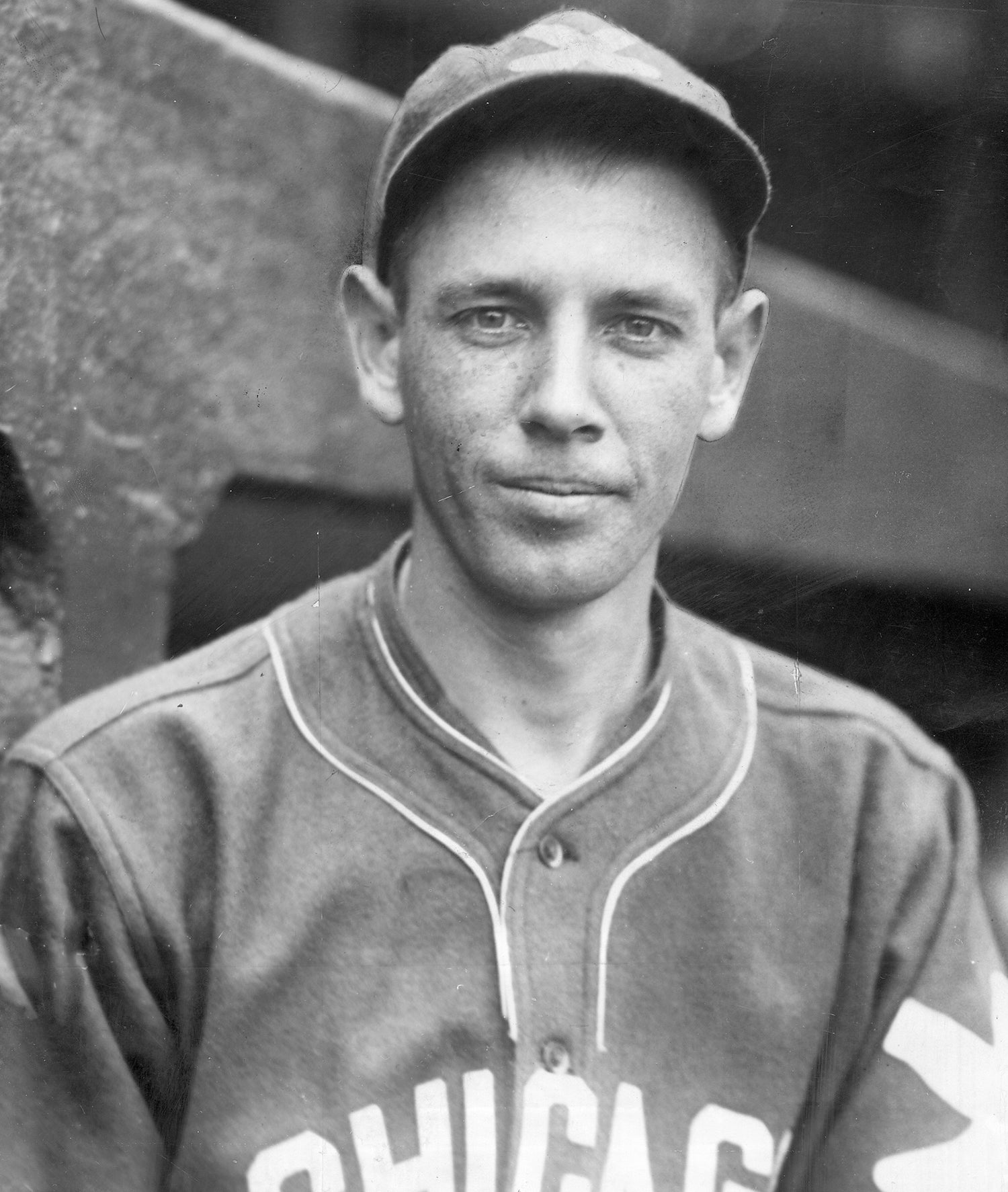

At first, Halladay struggled in Class A ball. But with help from former Blue Jays pitching coach Mel Queen, Halladay rebuilt his confidence along with his delivery. When he returned to the Blue Jays later that year, Halladay had fashioned a release point that created a darting, nearly unhittable fastball.

By the end of the 2002 season, Halladay – now committed to a grueling workout routine and incessantly studying videotape of hitters – was 19-7 with a 2.93 ERA in a league-best 239.1 innings.

In 2003, he was the AL Cy Young Award winner following a 22-7 campaign that featured 204 strikeouts against only 36 walks.

“There aren’t many pitchers that could do what he did,” Queen told the Toronto Star. “But Doc was able to do it because of the special type of individual he is.”

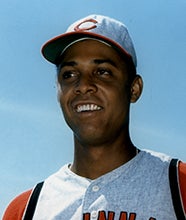

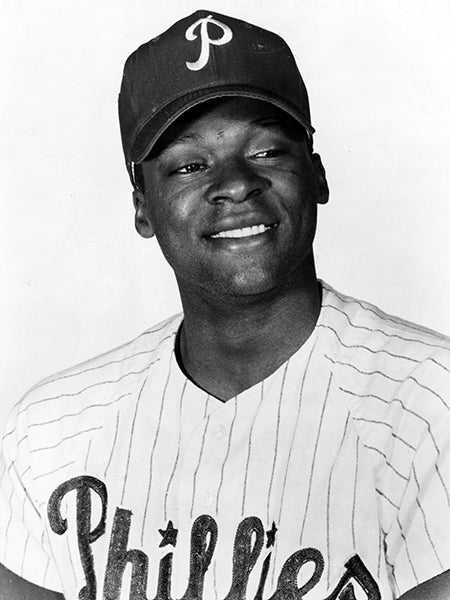

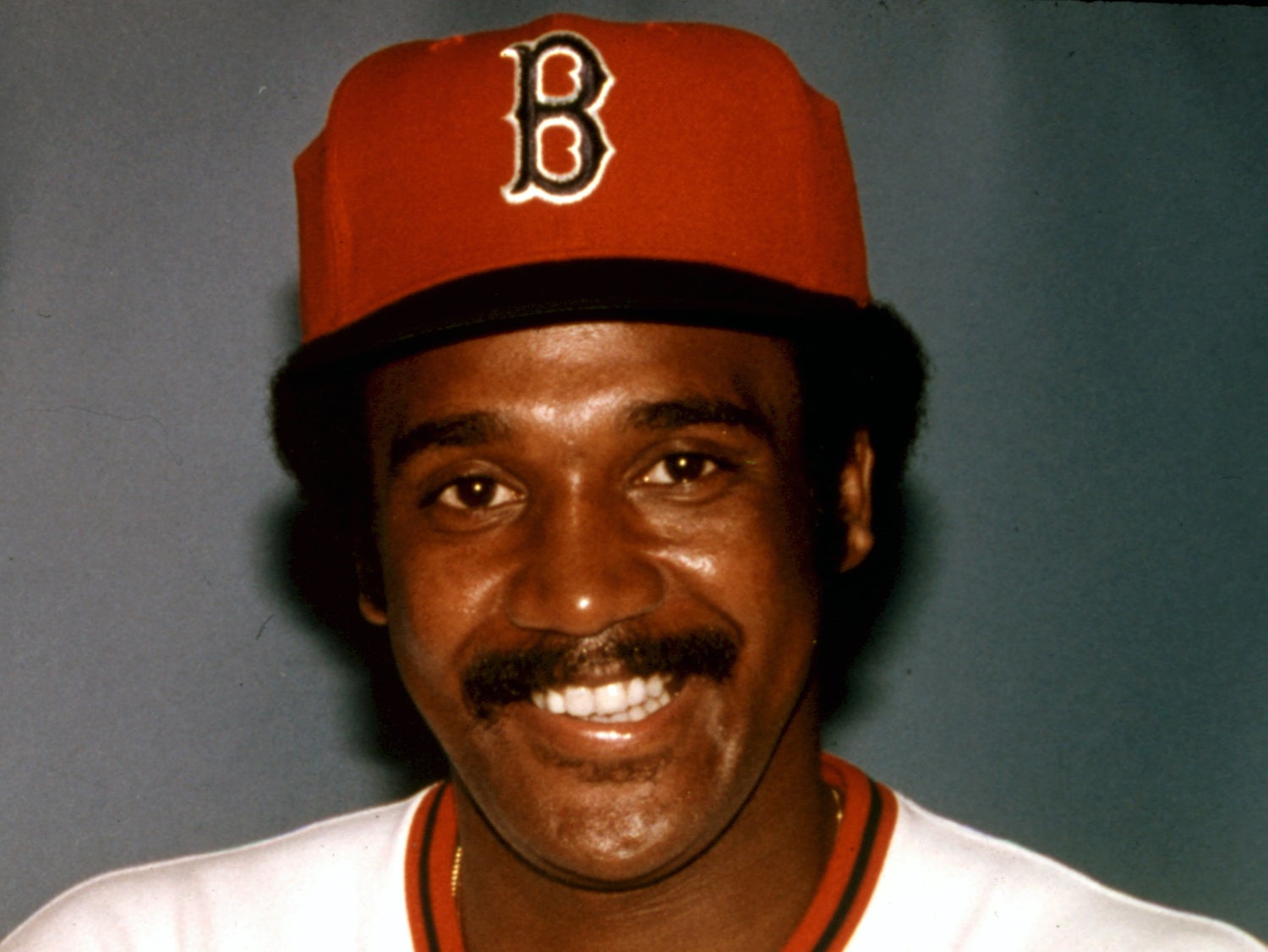

Aside from a truncated 2004 season due to shoulder problems, Halladay was at the top of his game from 2002-12. The Blue Jays traded him to the Phillies following the 2009 season, and in 2010 he posted a 21-10 record and a 2.44 ERA, throwing a perfect game on May 29 against the Marlins and then a no-hitter in Game 1 of the NLDS against the Reds on Oct. 6 – just the second no-hitter in postseason history. He won his second Cy Young Award after the season.

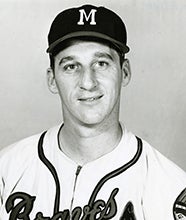

In 2011, he finished second the Cy Young Award voting after going 19-6 with a 2.35 ERA. But shoulder problems plagued him again in 2012, and after 13 starts, a 4-5 record and a 6.82 ERA in 2013, Halladay called it a career.

His final numbers: A record of 203-105, with a 3.38 ERA, 67 complete games and 2,117 strikeouts in 2749.1 innings. He led his league in complete games seven times, the most of any pitcher whose career began after World War II.

Halladay, who began flying as a teenager and whose father was a longtime commercial pilot, passed away when the private plane he was operating crashed into the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of nearby Tampa, Fla., on Nov. 7, 2017. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2019.