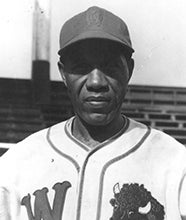

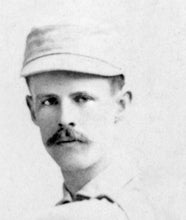

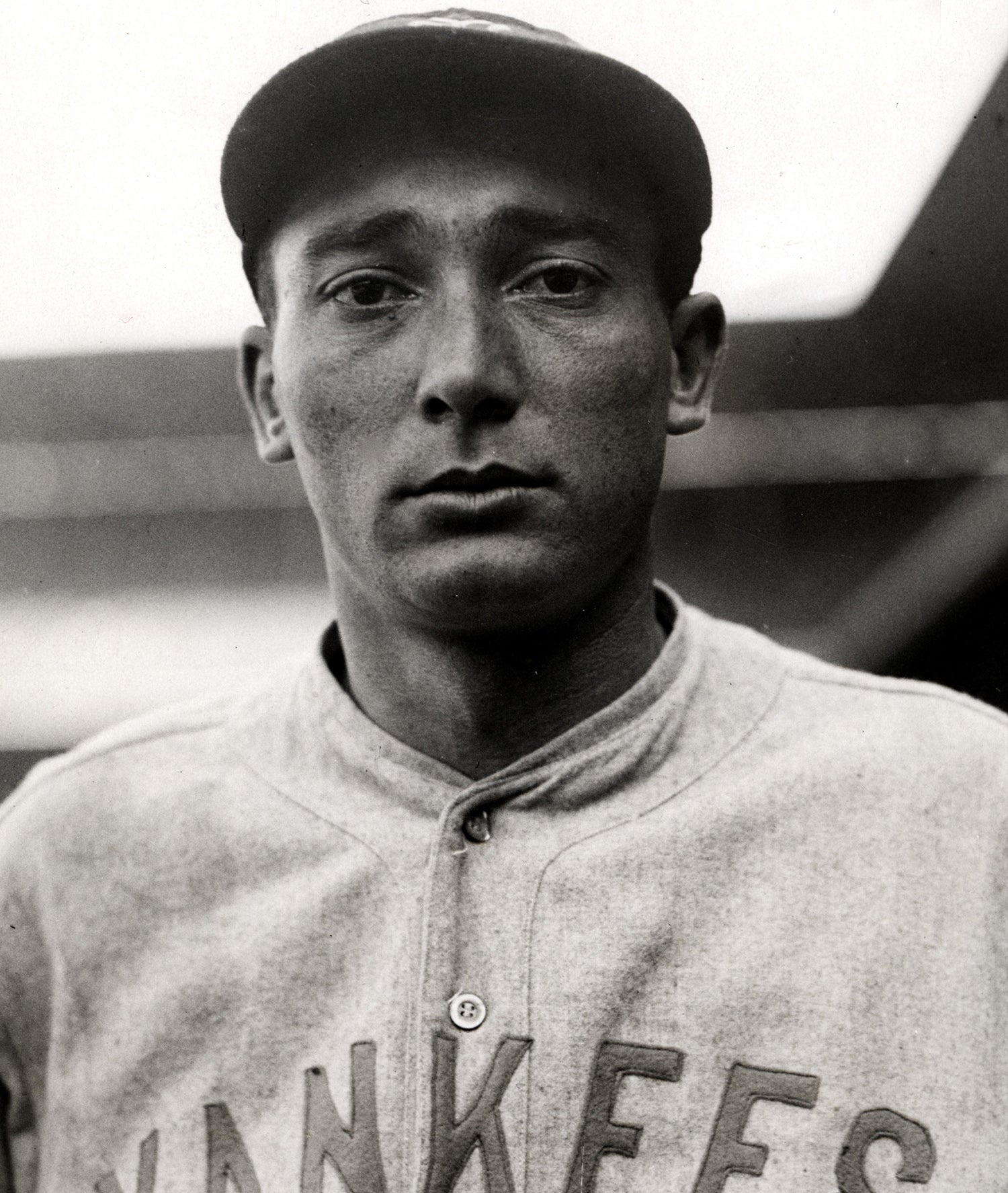

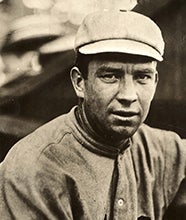

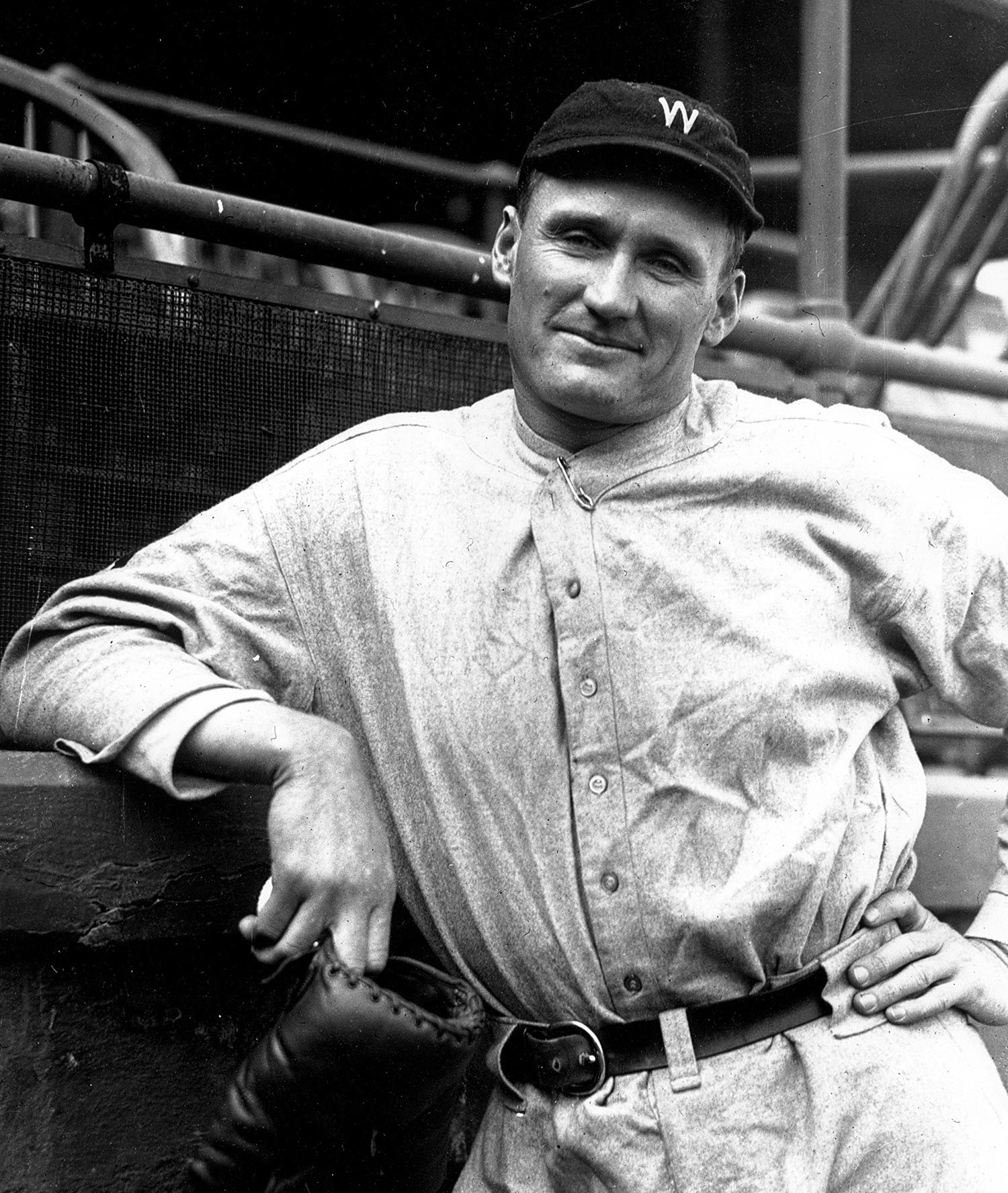

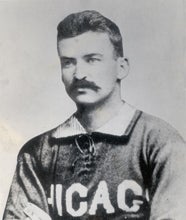

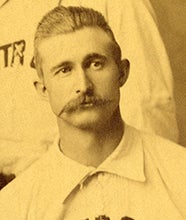

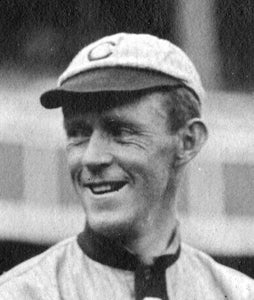

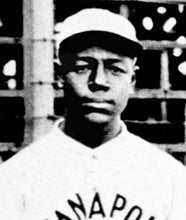

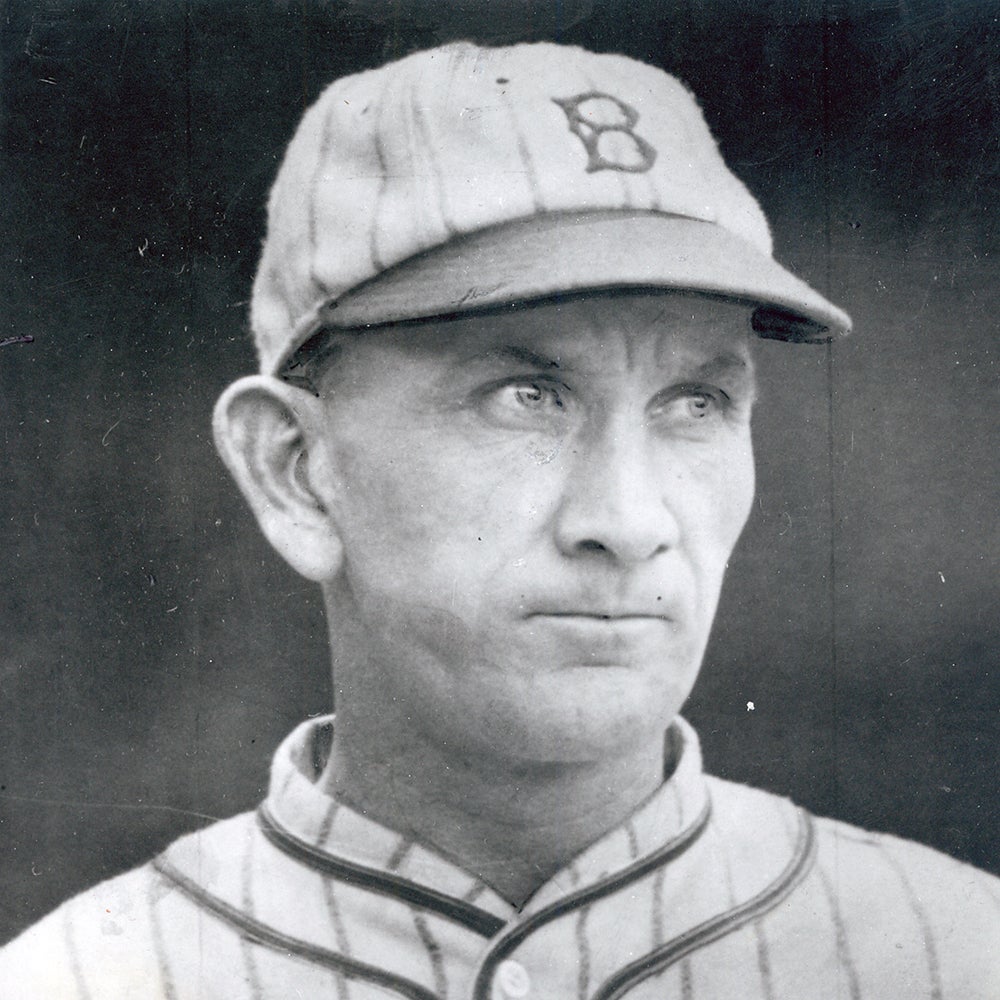

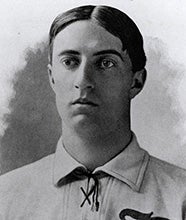

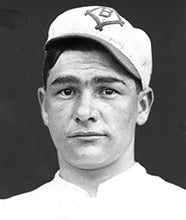

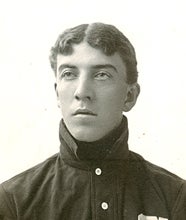

In the early years of Veterans Committee selections, electors were charged with identifying 19th century players worthy of Hall of Fame induction.

In 1939, the Museum’s inaugural year, the committee (then called the Centennial Commission) was comprised of just three men – Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, National League President Ford Frick and American League President Will Harridge.

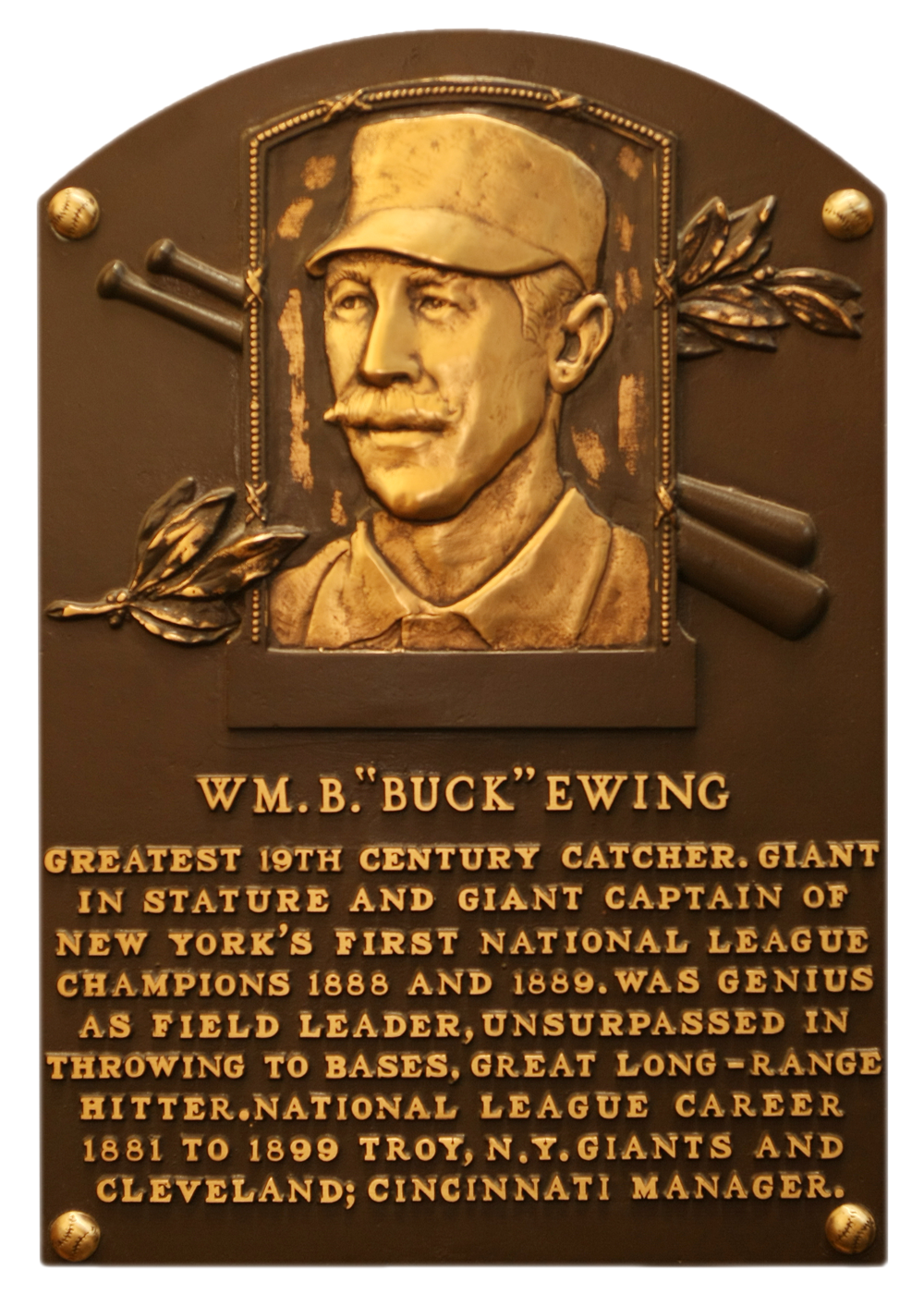

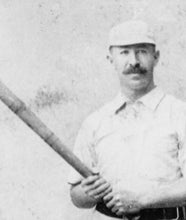

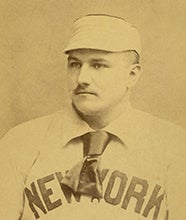

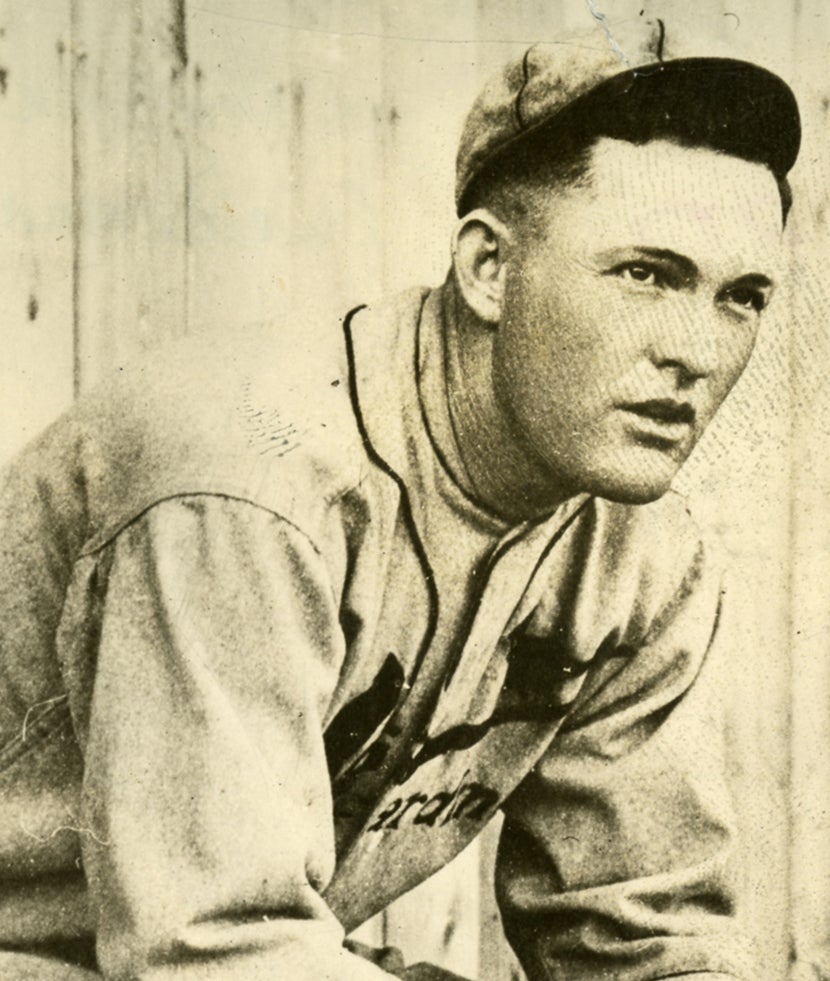

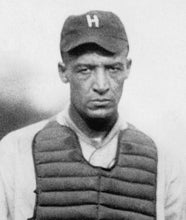

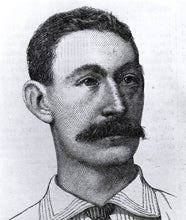

The men selected six to add to the Hall of Fame: Albert Spalding, Cap Anson, Charles Comiskey, Old Hoss Radbourn, Candy Cummings and the premier catcher of his time, Buck Ewing.

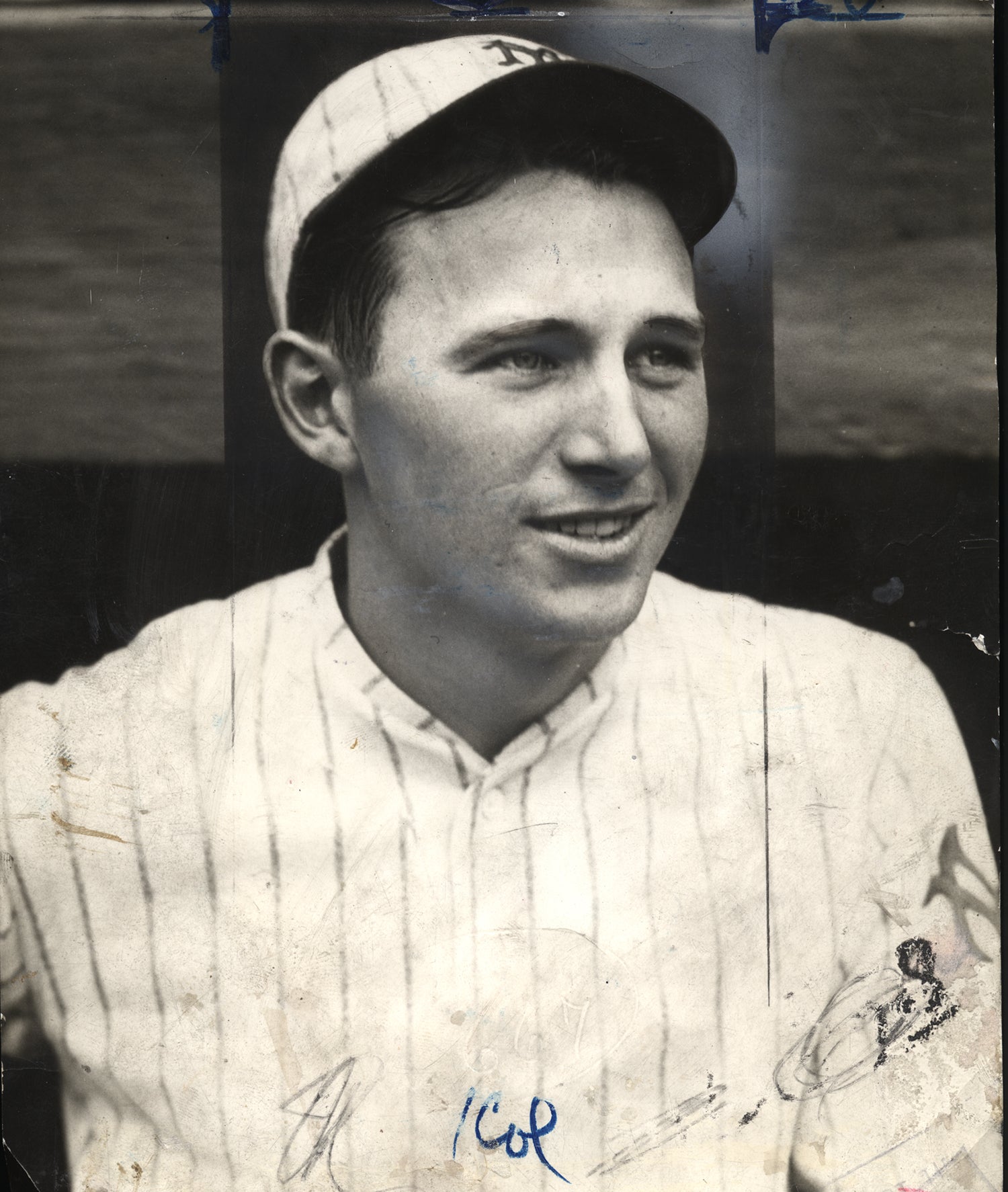

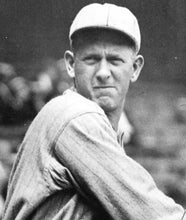

Today, Ewing’s reputation is sometimes obscured by the outstanding catchers who succeeded him. But witness the esteem in which he was held in ‘39, from the 1940 Official Baseball Guide:

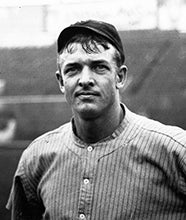

“William (Buck) Ewing is considered by many to have been the greatest all-around player who ever lived. Some go even further and rate Buck… the best ballplayer of all time. He could run, bat – and how he could throw! When he was catching, he would squat down behind the plate and seemingly hand the ball to whoever was playing second base.”

Connie Mack considered him the greatest catcher of all-time and was happy to tell anyone about it at the 1939 Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony.

In the 1919 Reach Guide, when he was less a distant memory, editor Francis Richter wrote of Ewing: “We have always been inclined to consider Ewing in his prime as the greatest player of the game from the standpoint of supreme excellence in all departments: Batting, catching, fielding, base-running, throwing, baseball brains – a player without a weakness of any kind, physical, mental or temperamental.”

Today, the honor of best catcher of “modern baseball” is an unsettled debate. But for the 19th century honor – before catchers were fully outfitted in protective equipment – there was no debate. Ewing was the acknowledged premier performer before “the tools of ignorance” as we know them were developed.

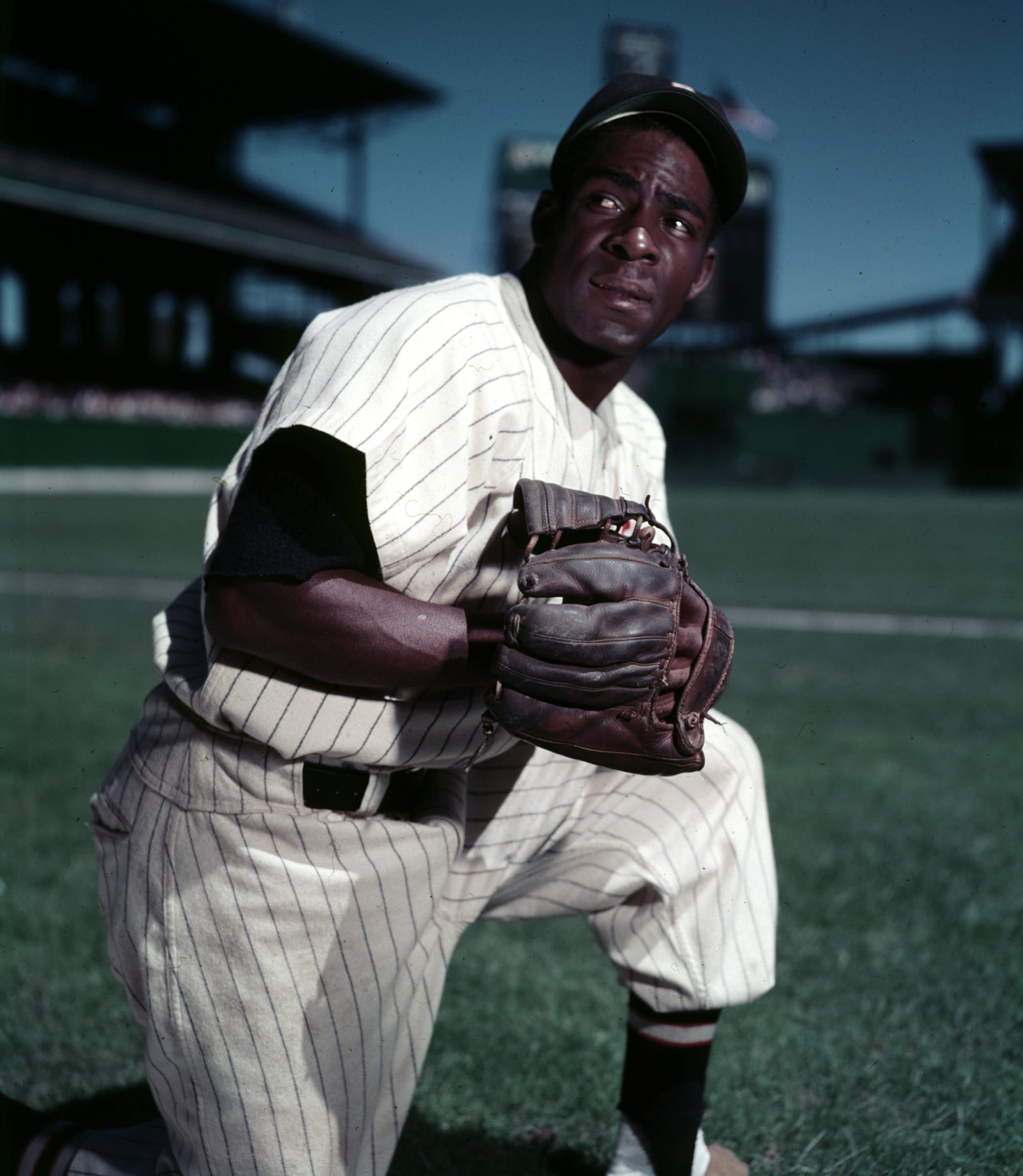

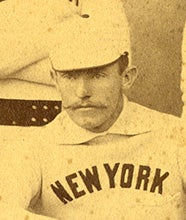

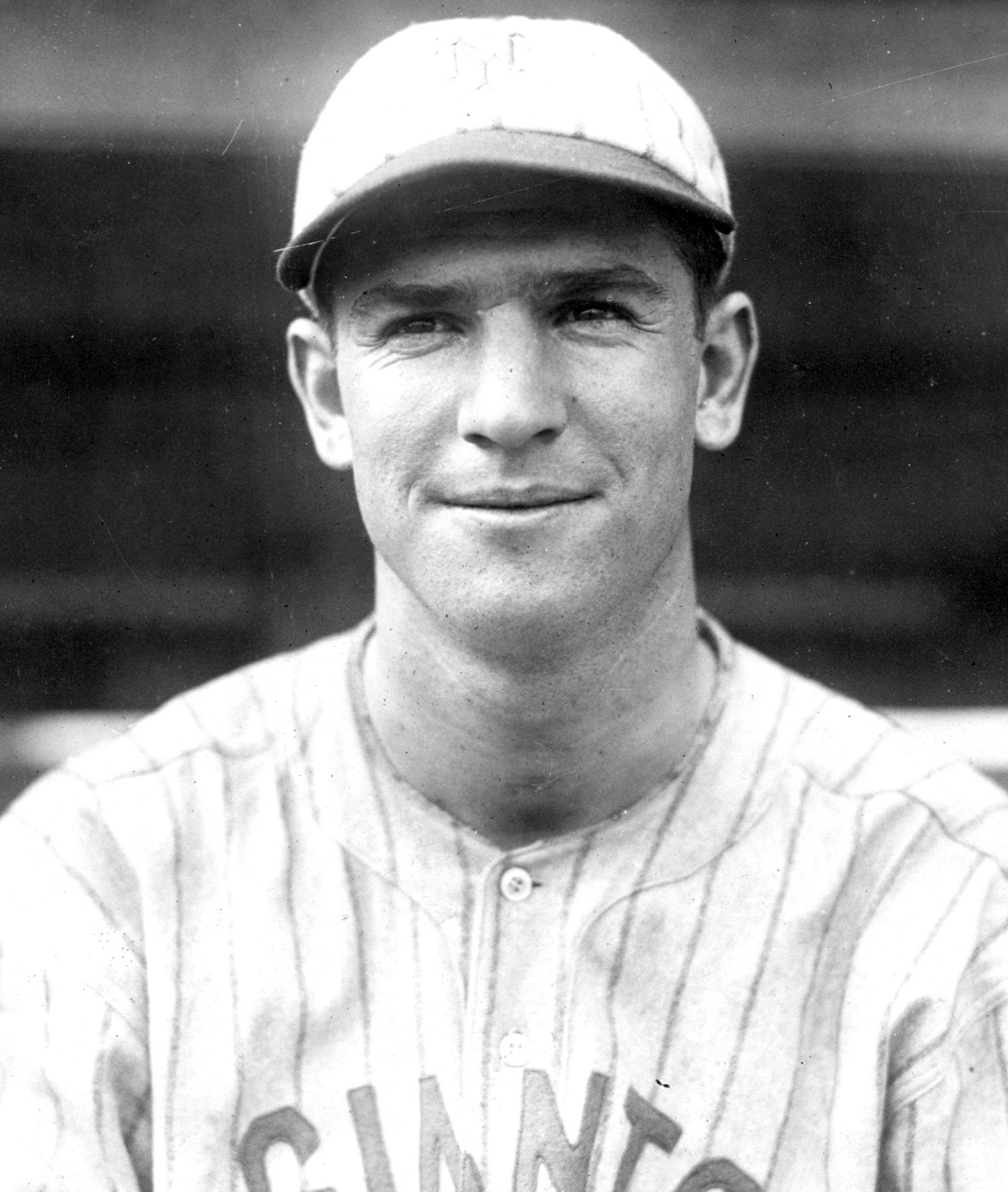

Ewing played 1,315 games between 1880 and 1897, with 636 of them coming behind the plate. The most games he ever caught in a season were a healthy 97 of the 126 scheduled games for the 1889 New York Giants. Without a chest protector, a sturdy mask or shin guards, it was a challenging position to say the least. Ewing may have worn early versions of a mask, and was said to be among the first to use a larger glove with added padding. And while the game was much different in those days, there was no reason to expect there were fewer foul tips careening off assorted body parts.

Undeterred by the hazards of the position, he was one of the first to crouch behind the plate, standing closer to the batter than most of his contemporaries and throwing runners out at second from a crouching position to save valuable seconds.

Ewing was born on Oct. 17, 1859, in Hoagland, Ohio, and moved as a baby with his family about 60 miles west to Cincinnati. There, he grew up in the very shadows of the birth of professional baseball.

As he began to appear in local amateur and semi-pro leagues, a playful sportswriter, Ren Mulford, Jr., called him “William Buckingham Ewing,” totally inventing the middle name, perhaps to acknowledge his classic Anglo bearing. From that he became Buck. At 20, he was signed by Rochester of the four-team National Association, a minor-league circuit. He played in only a handful of games before he signed with Troy of the National League, embarking on his 18-season major league career (including four as a player-manager, and then three as just a manager, taking him up to 1900).

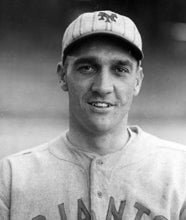

After Troy lost their big league club, a number of its players, Ewing included, were transferred to New York. Along with future Hall of Famers Tim Keefe, Mickey Welch, Roger Connor and John Montgomery Ward, Buck became a stalwart on a popular and talented Giants team. In 1883, Ewing led the league with 10 home runs. To put the figure in perspective, his teammate, Connor, hit just one. Connor’s 138 home runs would become the major league lifetime record until Babe Ruth came along.

In 1888, he succeeded Ward as team captain (much closer to “manager” than today’s captains), and helped lead the Giants to their first championships in’88 and ’89.

Ewing joined Ward in jumping to the Players League in 1890 and had his first experience as a manager, guiding the New York franchise to a third-place finish, before rejoining the Giants in 1891 when the new league folded.

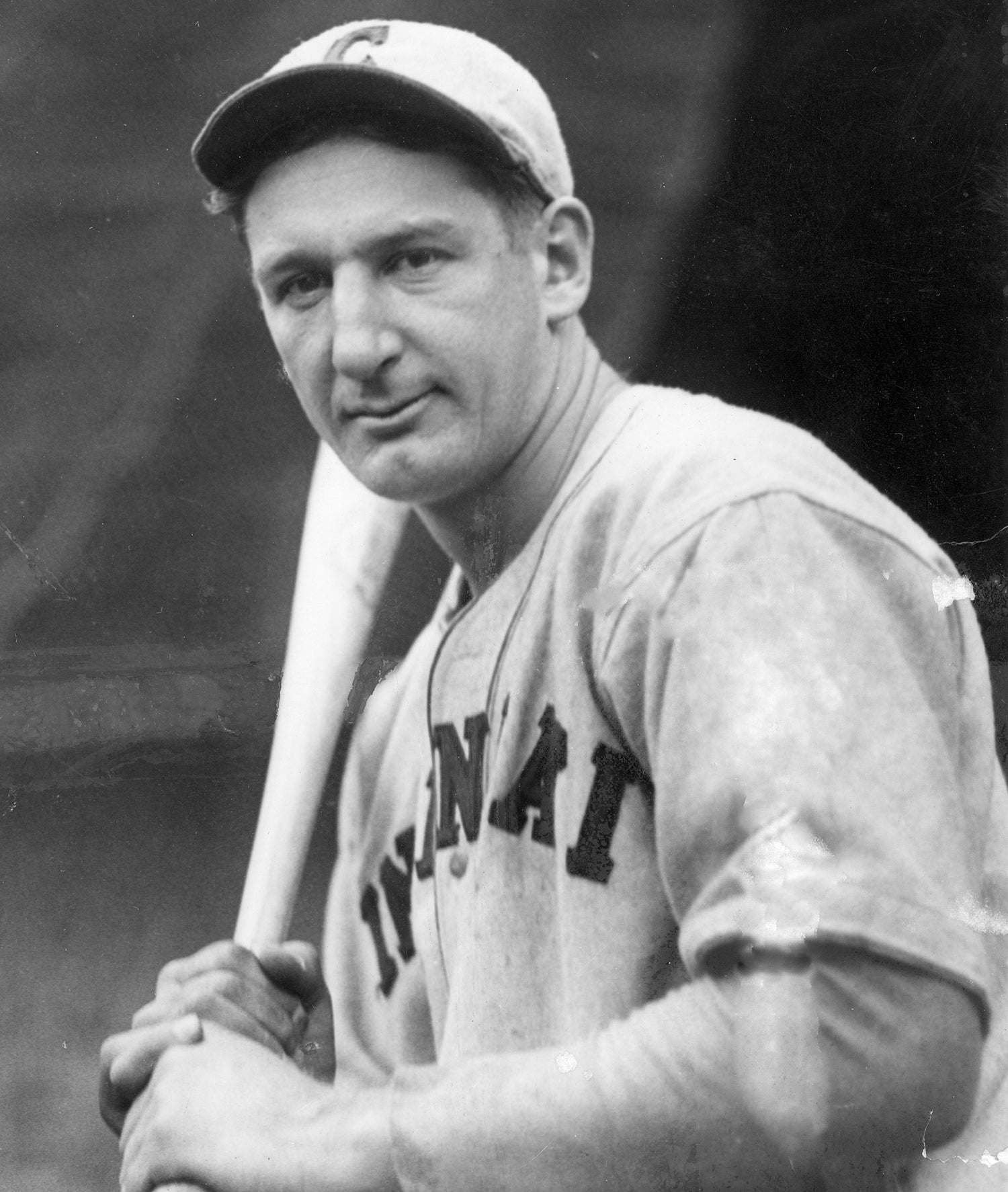

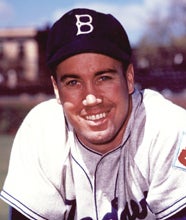

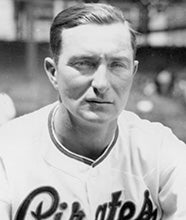

After two final years with the Giants, he played for Cleveland and hometown Cincinnati, managing those clubs and never finishing under .500. An injury to his throwing arm, suffered during a cold exhibition game in Connecticut in 1892, effectively ended his catching career and forced him to finish his playing career as first baseman. In 1900 he returned to the Giants as manager. In mid-season he was replaced by George Davis, marking the end of his pro baseball career.

Buck finished with a .303 lifetime batting average and the respect of most observers of the time as one of the elite all-around players in the game.

He retired to Cincinnati, coached a prep team, and was considered a wealthy man from real estate investments in the western U.S. But he suffered from diabetes and Bright’s Disease and passed away on Oct. 20, 1906. In his obituary, The New York Times called him “the greatest catcher in the country.”