- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Color of Diversity

#Shortstops: Color of Diversity

History was made at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium in 1971.

Nearly 50 years later, Jim Shearer found the perfect time to illustrate it.

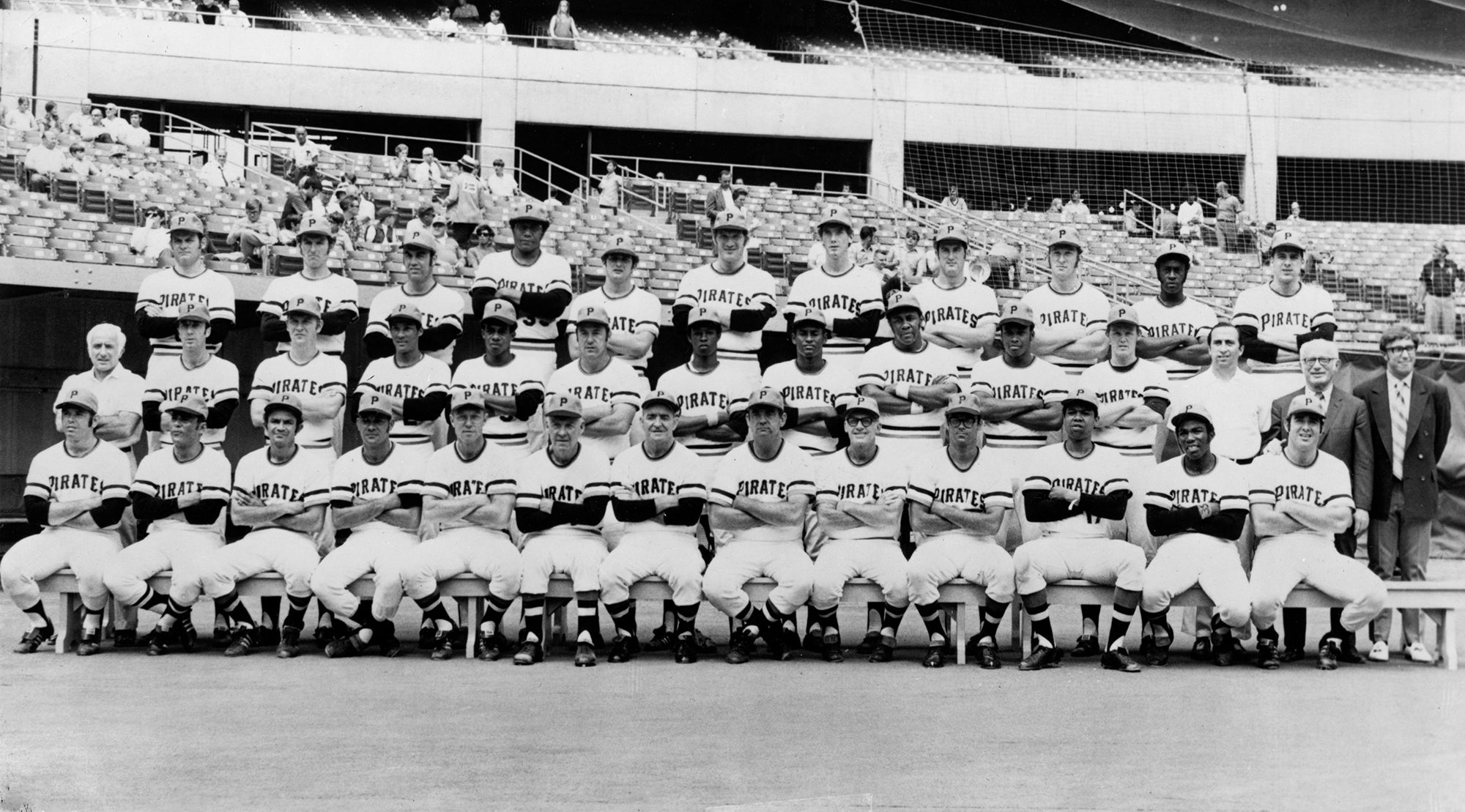

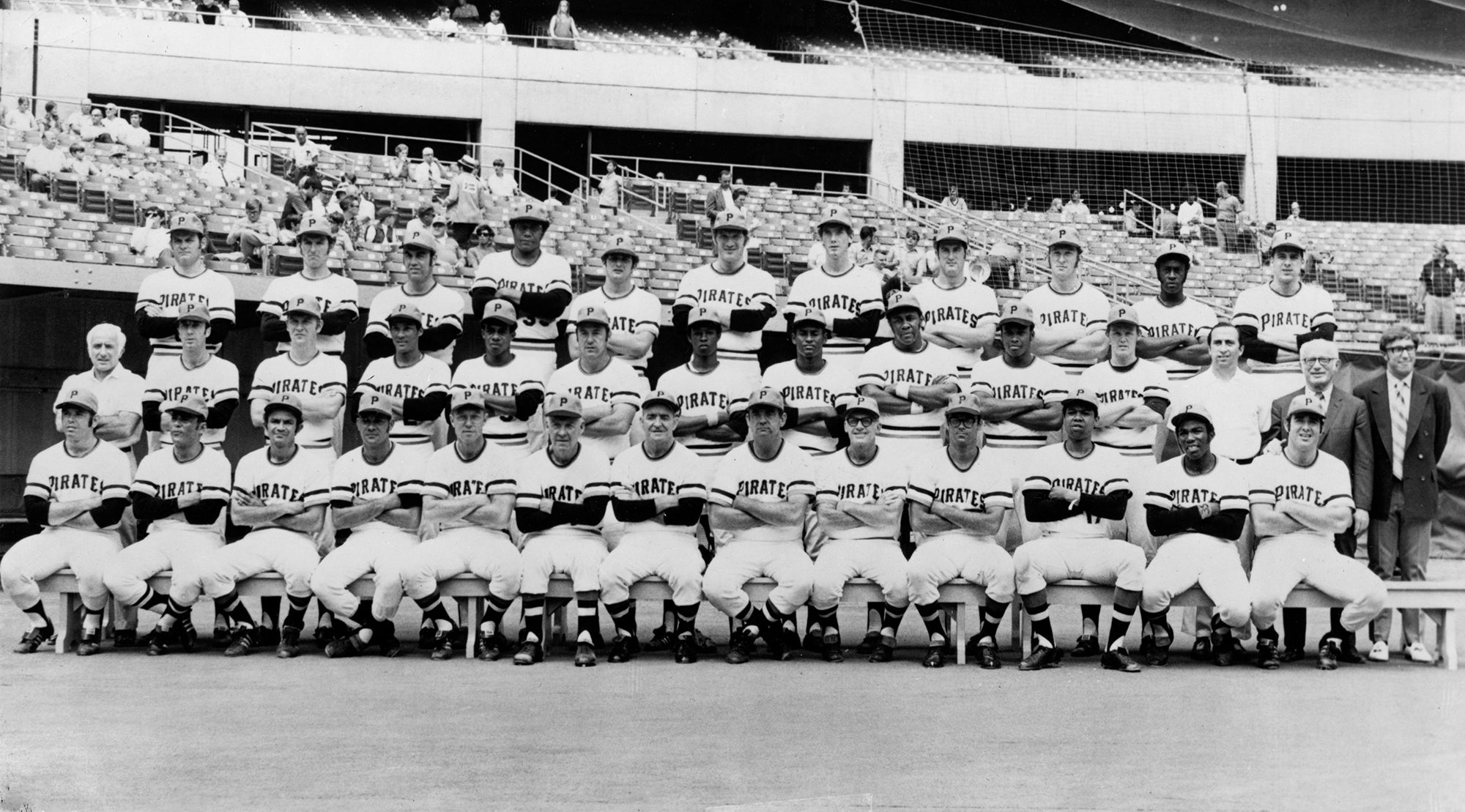

Shearer’s artwork, which is now part of the Hall of Fame’s collection, depicts the Pittsburgh Pirates lineup from Sept. 1, 1971. At first glance, it seems like it was just another regular season matchup against the Phillies. But the Pittsburgh lineup that played in that game held great historical significance: it marked the first time an AL or NL team had fielded an all-Black and Latino starting lineup.

Second baseman Rennie Stennett led off for Pittsburgh, while center fielder Gene Clines batted second, future Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell batted third and fourth, catcher Manny Sanguillén batted fifth, third baseman Dave Cash batted sixth, first baseman Al Oliver batted seventh, shortstop Jackie Hernández hit eighth and pitcher Dock Ellis batted in the nine hole.

Due to a newspaper strike happening in the city of Pittsburgh at the time, there was no local newspaper coverage of the game. At first, many people didn’t even realize the history that had just been made.

“The cool thing about it is, for an inning and a half or two innings, no one even knew it,” Shearer said. “It was almost like a little brief utopia, where you could have these nine Black and Latino players on the field, and no one really thought twice about it.”

In Shearer’s illustration, all nine players are depicted standing side by side, with Clemente in the center. Below the players, a short caption explains the significance of the moment, noting that 24 years prior to 1971, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in the NL. It also adds that two successful Negro League franchises, the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords, once played in Pittsburgh.

The Pirates won the game against the Phillies that day, 10-7, thanks to multi-hit efforts from six members of the starting lineup. Pittsburgh would go on to win the World Series that year as well, defeating the Baltimore Orioles in seven games.

Shearer, who works as a host on Sirius XM VOLUME, is a Pittsburgh native who now lives in New York City. He was inspired by the work of artist Bruce Stark at an early age, and began drawing sports and music-related cartoons when he was in grade school.

Amid the racial justice movements of 2020, Shearer felt it was the right time to use his talent to document such a significant moment in baseball and American history.

“Pittsburgh loves sports, so that breaks down our barriers,” Shearer said. “You can talk about sports, and then you can sort of dive into other things. So that was just sort of my entrée into talking about race with people who didn’t want to talk about it.”

When he completes a new drawing, Shearer often prints out a few hundred copies for his father, who will pass them out to any sports fans he encounters.

“He’s the type of guy that will randomly strike up a conversation with a stranger, and say, ‘Hey, do you like the Penguins? Well, here’s a poster from my son.’ So I knew that if I printed him off a giant stack of those, he would eventually go out and about and sort of hand them off to people,” Shearer said. “He’s had these little minor breakthroughs about having conversations about race that probably wouldn’t have happened otherwise.”

Shearer’s uncle, an avid baseball fan, visited the Hall of Fame in 2020 and brought several copies of Shearer’s piece along with him. He approached a Hall of Fame staff member about donating a copy to the collection and was given a business card to pass along to his nephew.

“I thought, oh, I’ll email the Hall of Fame just to humor him and then I’ll say, ‘Hey Uncle Jack, I emailed them. I never heard back, but just so you know, I emailed them,’” Shearer said. “But amazingly, someone did get back to me.”

The piece was ultimately accepted, and is now preserved within the Hall of Fame’s archives.

It’s an honor for Shearer to have a piece of his artwork preserved in the Hall of Fame’s collection – but it’s not exactly what he dreamed of when creating the piece. His goal for his piece was simple: Start important conversations.

“Whether you show it on your website, or whether it does get hung on a wall someday – if we could have those conversations and break down this uncomfortableness and awkwardness to ever talk about race; if we could actually have those conversations, then that’s a small win for me,” Shearer said.

Janey Murray was the digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Clemente’s teamwork helped make historic Pirates 1971 lineup a reality

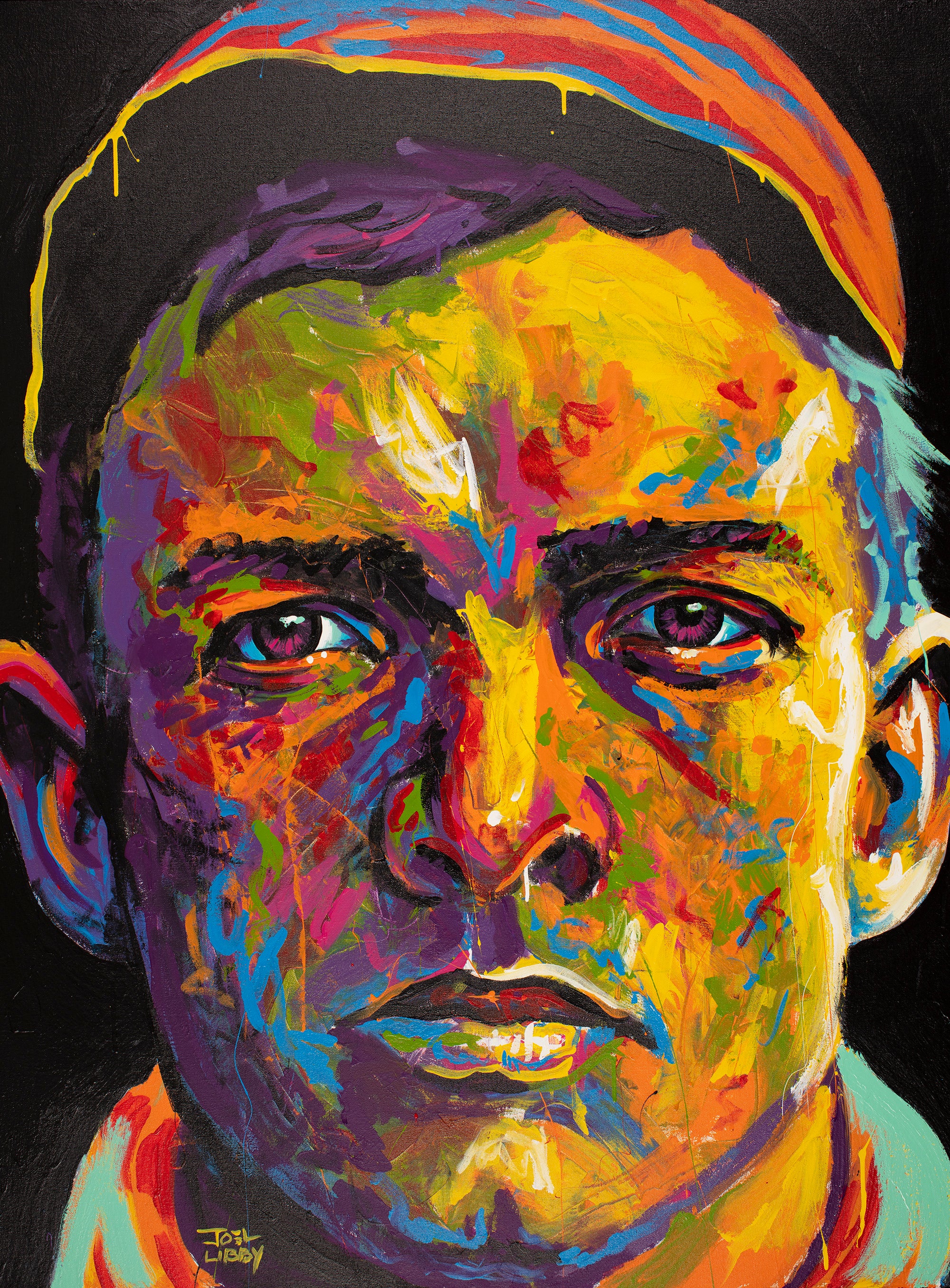

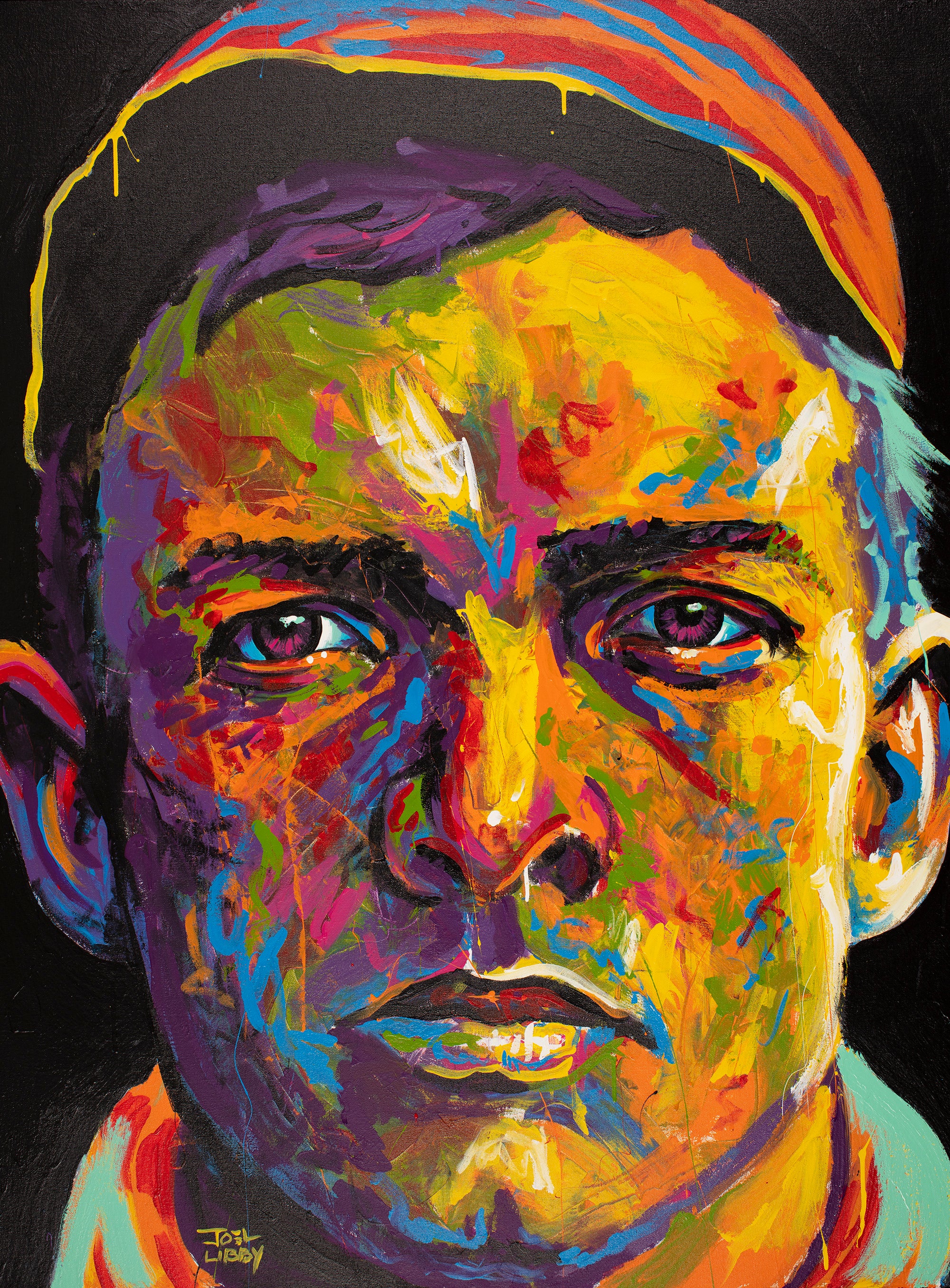

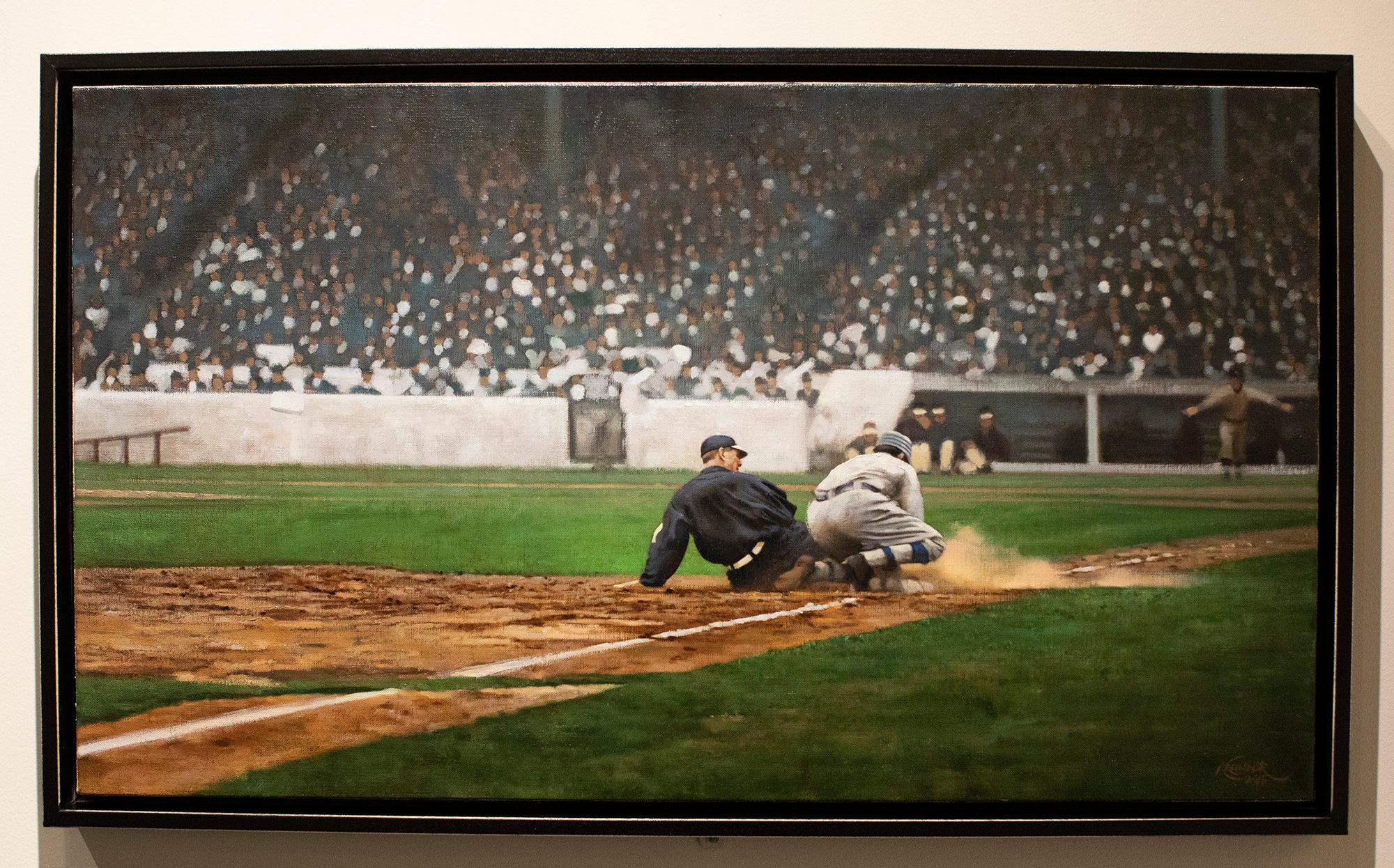

#Shortstops: Painting America’s Pastime

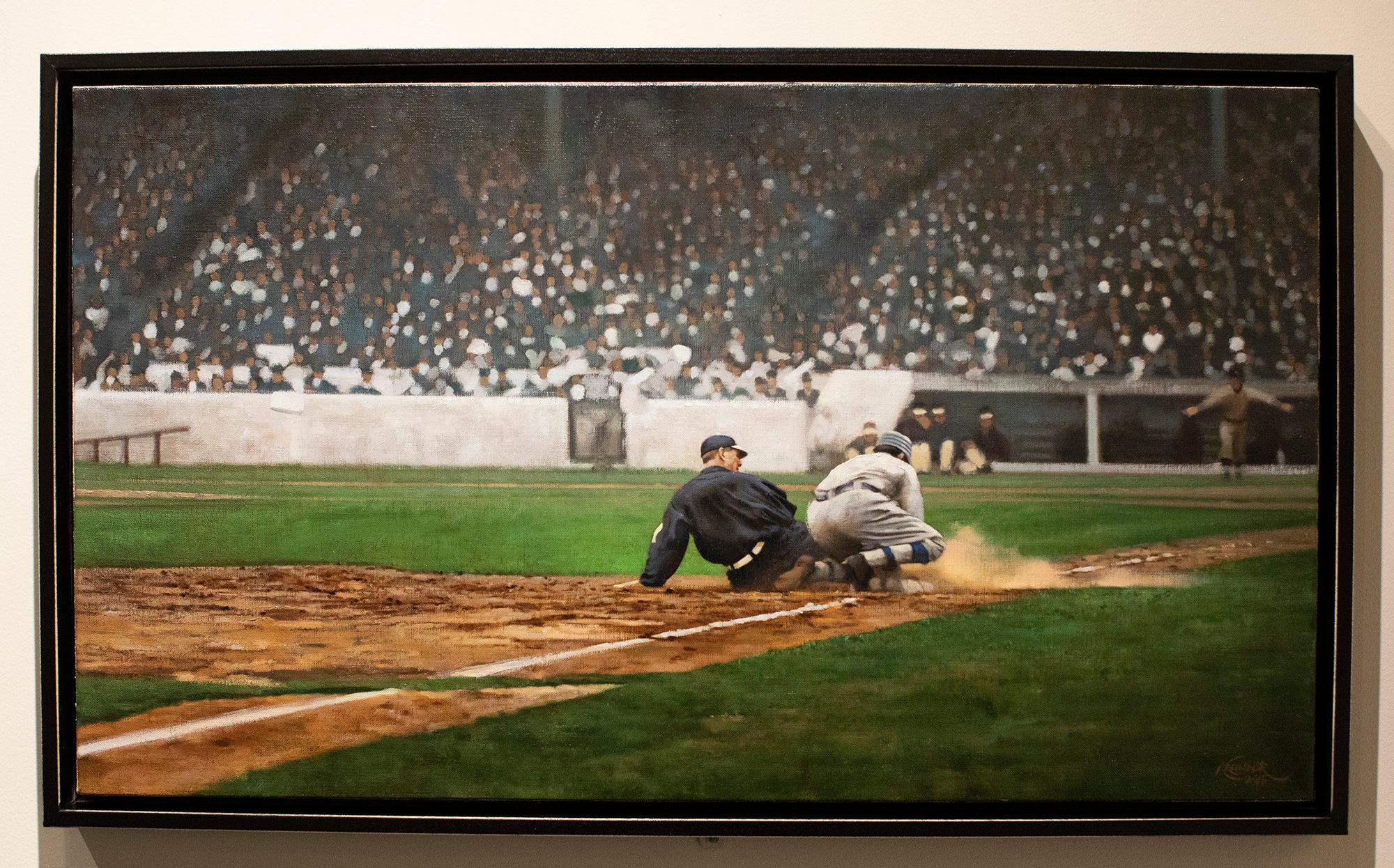

#Shortstops: Striking Mathewson

Clemente overcame societal barriers en route to superstardom

Clemente’s teamwork helped make historic Pirates 1971 lineup a reality

#Shortstops: Painting America’s Pastime