- Home

- Our Stories

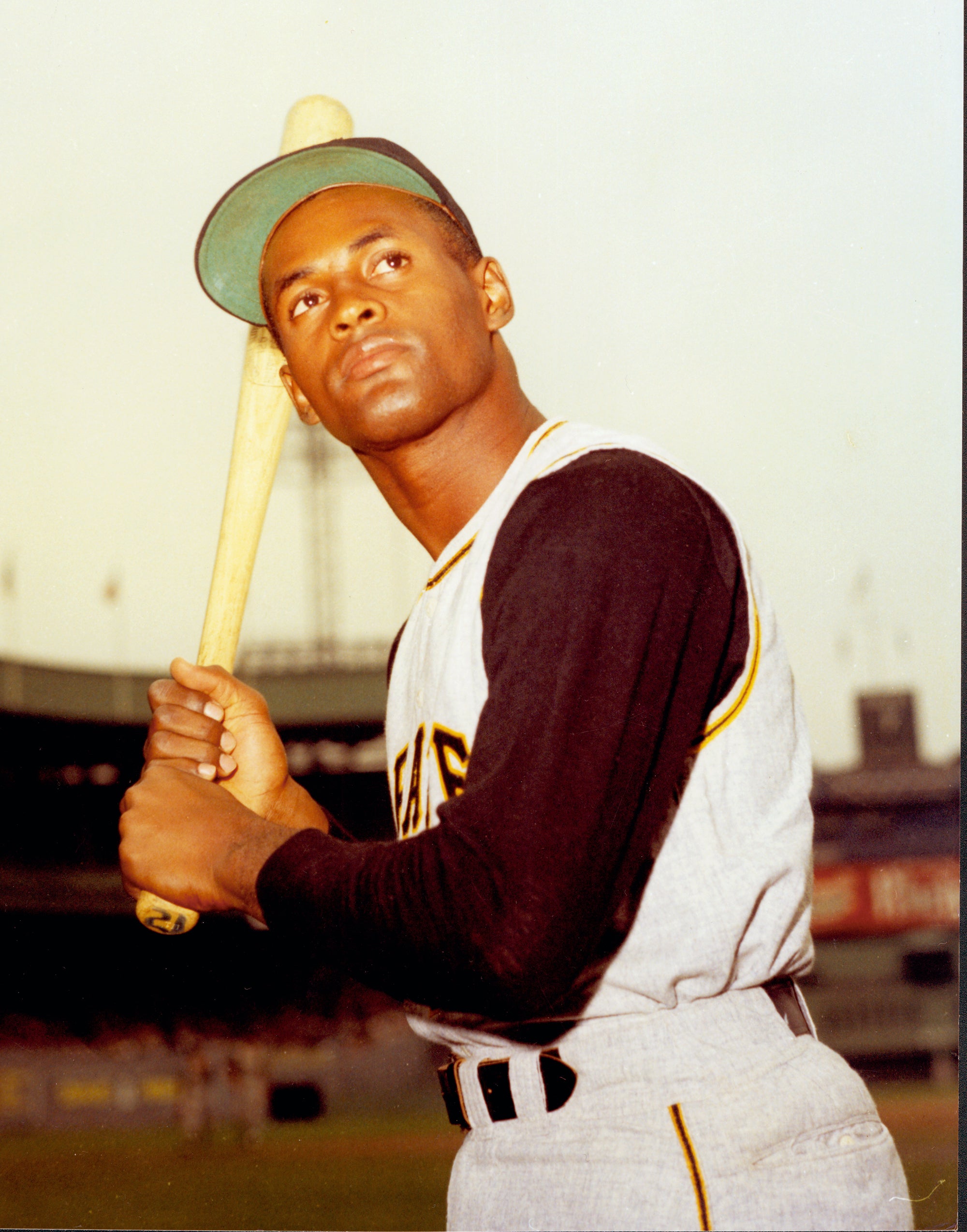

- Clemente’s teamwork helped make historic Pirates 1971 lineup a reality

Clemente’s teamwork helped make historic Pirates 1971 lineup a reality

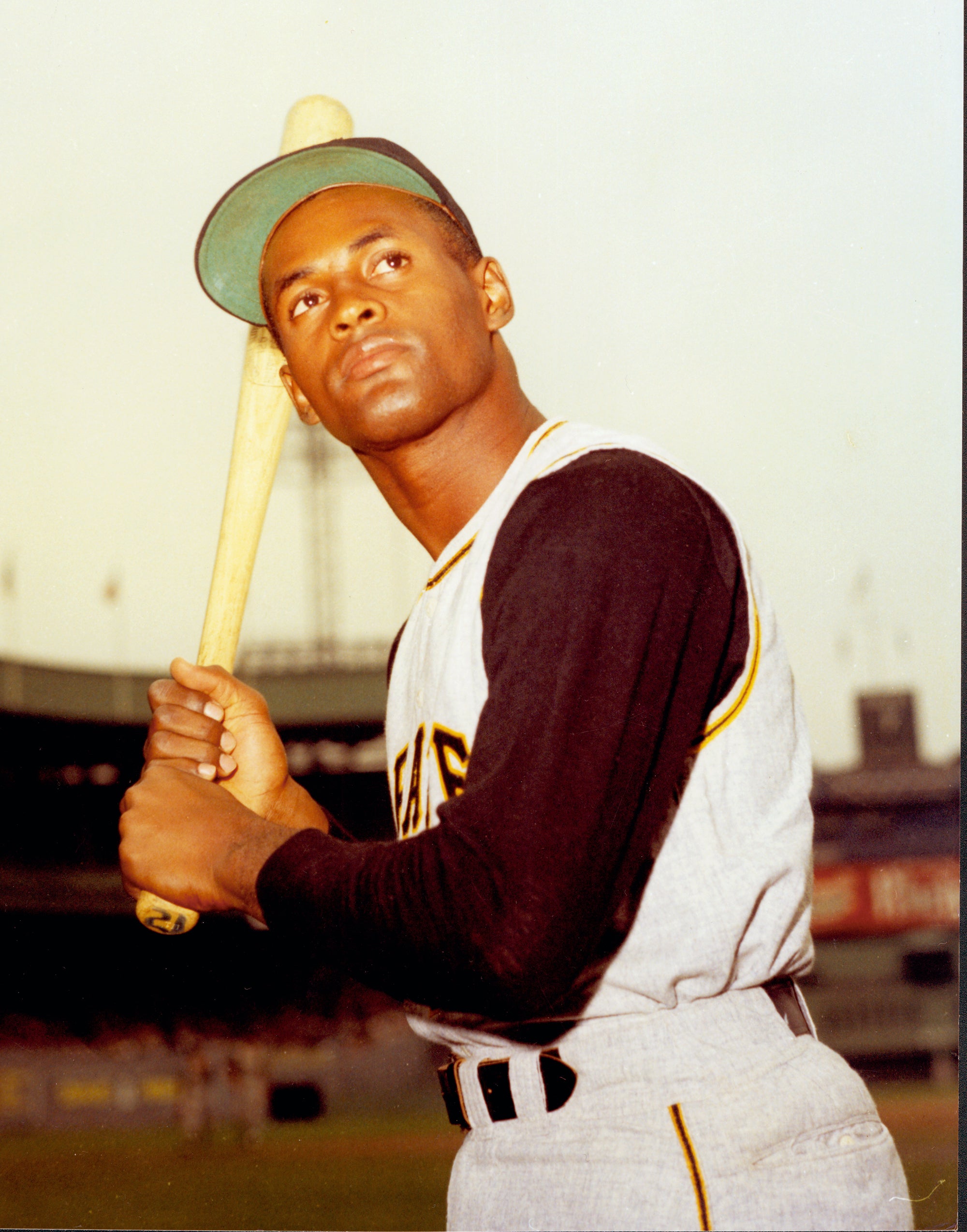

Roberto Clemente was not the first Latino to play in the major leagues. Nor was he the first Latino who happened to be dark-skinned. Those honors belonged to other players.

While being the first in those categories might have brought him even more recognition, they don’t diminish Clemente’s status as a crucial component to the game’s racial and ethnic history.

Those aforementioned milestones also involved accomplishments by a singular player. But another milestone, one that is perhaps even more significant, did not escape Clemente. It was a team milestone, something accomplished by the Pittsburgh Pirates 50 years ago. On Sept. 1, 1971, the Pirates became the first AL or NL team to field an all-black, or all-minority lineup. Clemente was part of the lineup that day, a fitting inclusion for a player who willingly spoke up about issues affecting Latino players of his era.

Earlier in 1971, Clemente had spoken at length about race in a lengthy interview with Milton Richman, the longtime baseball writer for United Press International. For much of the 1950s and 60s, few players – Black, Latino, or white – spoke openly about the unjust treatment of players who were regarded as minorities. Clemente, however, was one of the exceptions. As he stated clearly in his talk with Richman: “Anytime I feel something is wrong, I’m gonna say something. Baseball has changed in many ways since I first came up to the big leagues [in 1955]. Players feel they can speak up much more now than they did then. I spoke up even then.”

In the decade and a half that followed Clemente’s arrival in the major leagues, he had succeeded in improving perceptions about minorities, both Latino and Black. “My greatest satisfaction comes from helping to erase the old opinion about Latin American and black ballplayers,” Clemente told Richman. “People had the wrong opinion [about us]. They never questioned our ability, but they considered us inferior in our station of life. Simply because many of us were poor, we were thought to be low class. Even our integrity was questioned. I don’t blame the fans for that. I blame the writers. They made it look like we were something different from the white players. We’re not. We’re the same.”

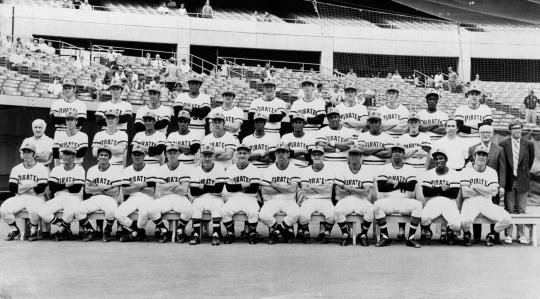

With some teams, the negative sentiments expressed about minority players sometimes spilled over into relationships among teammates. In some clubhouses, tension between Black and white players existed, even if it did not manifest itself in the form of open arguments or fights. With the Pirates of 1971 featuring such remarkable diversity – approximately half of the team consisted of Black and Latino players and the other half consisted of white players – the atmosphere might have seemed susceptible to racial tension. Yet, with the Pirates, such problems rarely occurred.

Players like Clemente, Gene Clines, Steve Blass, and Dave Giusti, and a respected coach named Dave Ricketts, helped create a clubhouse where players got along across racial and ethnic lines. Pirates players regularly instigated bouts of ribbing and joking, with much of the humor centered on race. Clemente and Giusti, an Italian American, needled each other to the point of bringing the entire clubhouse to laughter.

“The by-play between [Clemente] and Giusti became almost a ritual for us,” wrote Blass in an article for Sport Magazine that ran two years later. “Robby was our player representative before Dave, and when something would come up, he’d say, ‘When I was the player rep, we never had these kinds of problems. But you give an Italian a little responsibility and look what happens.’ ”

Giusti took no offense, because he knew that Clemente was kidding. And Clemente reacted similarly whenever Giusti made a racially-tinged humorous remark in return.

On other teams, such joking might have gotten out of hand and resulted in outright warfare in the clubhouse. For the Pirates, there was no such difficulty. Giusti says that two players deserved credit for keeping the team unified and close-knit.

“The reason why we did get along so well is because of the leadership that we had with a Clemente and a [Willie] Stargell – mainly,” Giusti told this writer during a visit to Cooperstown in the late 1990s. “It was just understood that there was instant respect for those two, and also respect for anyone else.

“You know, Clemente was outstanding in that area. I can recall a number of times when people were having problems, and he would sit people down, including myself, and just go over things. [He’d say] that baseball is not everything, it’s your family and how you get along with people that are more important.”

With strong relationships between Pirate teammates, and with an unprecedented level of diversity on the roster, the Pirates usually featured lineups that had anywhere from five to seven Black and Latino players. But none of their managers had ever written out a lineup featuring nine players from minority backgrounds. The Pirates had come close in 1967, when manager Harry “The Hat” Walker filled out a lineup card that had eight players who were either Latino or African American. But there was one exception. The pitcher that day was Dennis Ribant, a young white right-handed pitcher from Detroit.

That all changed on the first day in September of 1971.

That afternoon, while sitting in his office at Three Rivers Stadium, Bucs manager Danny Murtaugh made out the following lineup card against the Philadelphia Phillies and veteran left-hander Woodie Fryman.

Rennie Stennett 2B

Gene Clines CF

Roberto Clemente RF

Willie Stargell LF

Manny Sanguillén C

Dave Cash 3B

Al Oliver 1B

Jackie Hernández SS

Dock Ellis P

Ordinarily, against a left-handed pitcher, Bob Robertson would have played first base. But for reasons that remain unknown to this day, Murtaugh benched Robertson in favor of Oliver. At third base, Richie Hebner would have been the usual choice to play, but he was hurt that day, forcing Murtaugh to move Cash from second to third, and creating space for Stennett, a Panamanian, at second base.

Over the first three innings, the Pirates’ all-black lineup pounded the Phillies for nine runs. That onslaught bailed out starting pitcher Dock Ellis, an All-Star having a rare bad day in 1971. Ellis was knocked out in the second inning and gave way to Bob Moose and then Bob Veale. Luke Walker, a white pitcher from Texas, then came in to pitch six brilliant innings of relief and earn a 10-7 victory for the Pirates.

After fielding the first all-black lineup in the AL or NL on Sept. 1, 1971, Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh (pictured above) downplayed his role in the event, stating that he simply put the best nine athletes in the lineup for the game that day. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Not surprisingly, Clemente played a big part in the Pirates’ win. He collected two hits in four at-bats, scored two runs, and drove in two. The two-hit day lifted Clemente’s season average to .341, an especially impressive mark for a player who had just turned 37.

After the game, a reporter asked Murtaugh about the significance of having fielded the first all-black lineup. As Steve Blass recalls, Murtaugh tried to downplay both the significance of the situation and his own role in writing out the lineup.

“The thing I remember about it, when he was interviewed afterwards, Murtaugh said, ‘I put the nine best athletes out there. The best nine I put out there tonight happened to be black. No big deal. Next question.’ ” In subsequent years, most Pirate players interviewed on the subject have expressed the belief that Murtaugh, from the beginning, was fully aware that all nine Pirates were black, but did not want to bring more attention to himself. In their opinion, Murtaugh did not intentionally include nine black players and was not trying to make any kind of social statement; rather, the manager was simply putting out the lineup that he felt was best suited to win that day. Unfortunately, there are no published comments from Clemente about the all-black lineup. The lack of a Clemente reaction is likely attributable to the newspaper strike going on in the city of Pittsburgh at the time. There was no local newspaper coverage of the game, only radio and TV reporting. If someone had asked Clemente about the all-black lineup, what might he have said? Perhaps he would have given that all-knowing look of his and curtly told reporters, “It’s about time.” It’s also likely Clemente would have expressed pride over the situation, knowing the incredibly important role the Black and Latino members of the Pirates were playing on a first-place team. Six weeks later, Clemente would have much more to say, as the Pirates took on the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. That’s when essentially this same group of Pirates, albeit without an actual all-black starting lineup, but with a team featuring an unprecedented level of integration in 1971, would make another meaningful statement.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Clemente’s remarkable life explored throughout ’21

Clemente overcame societal barriers en route to superstardom

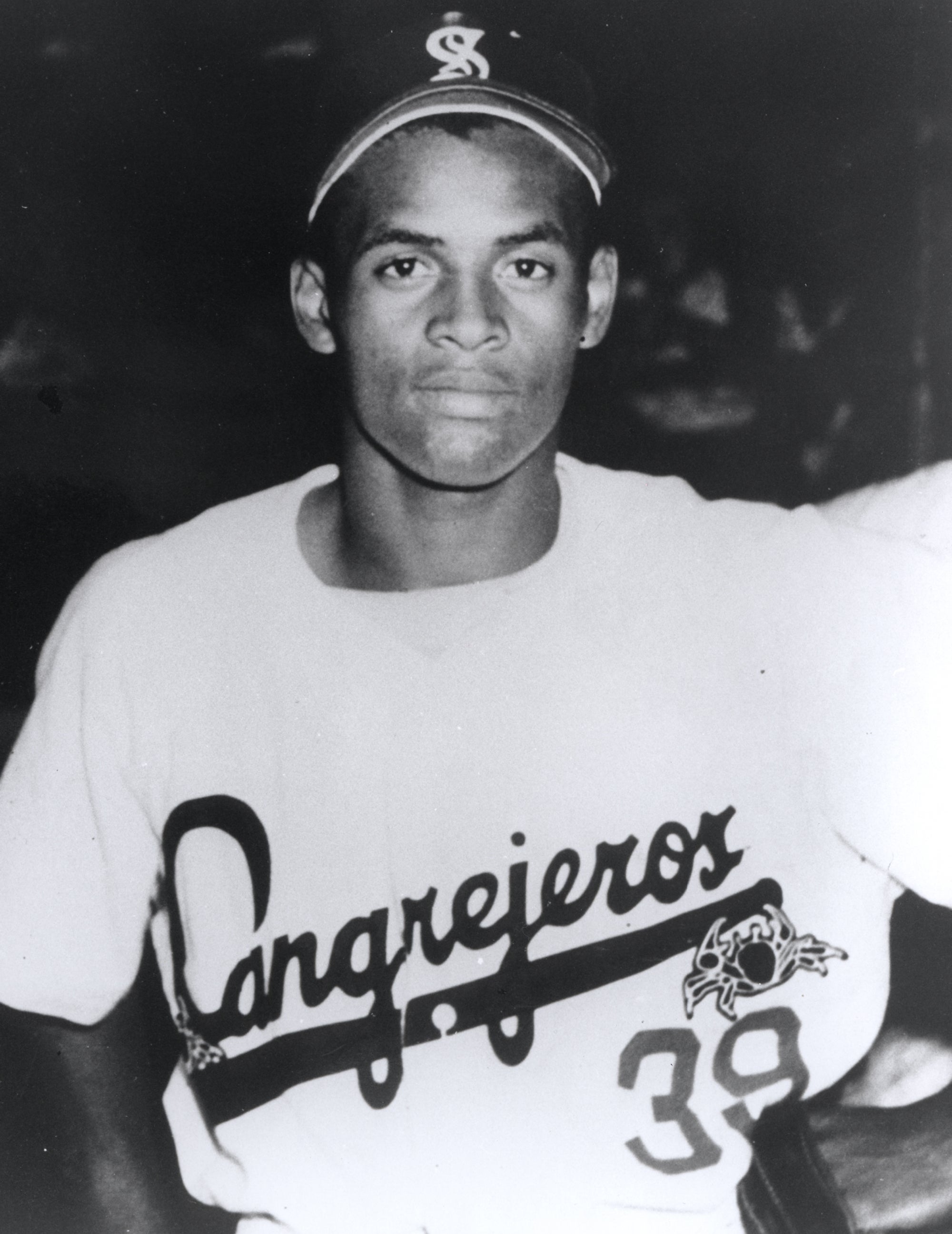

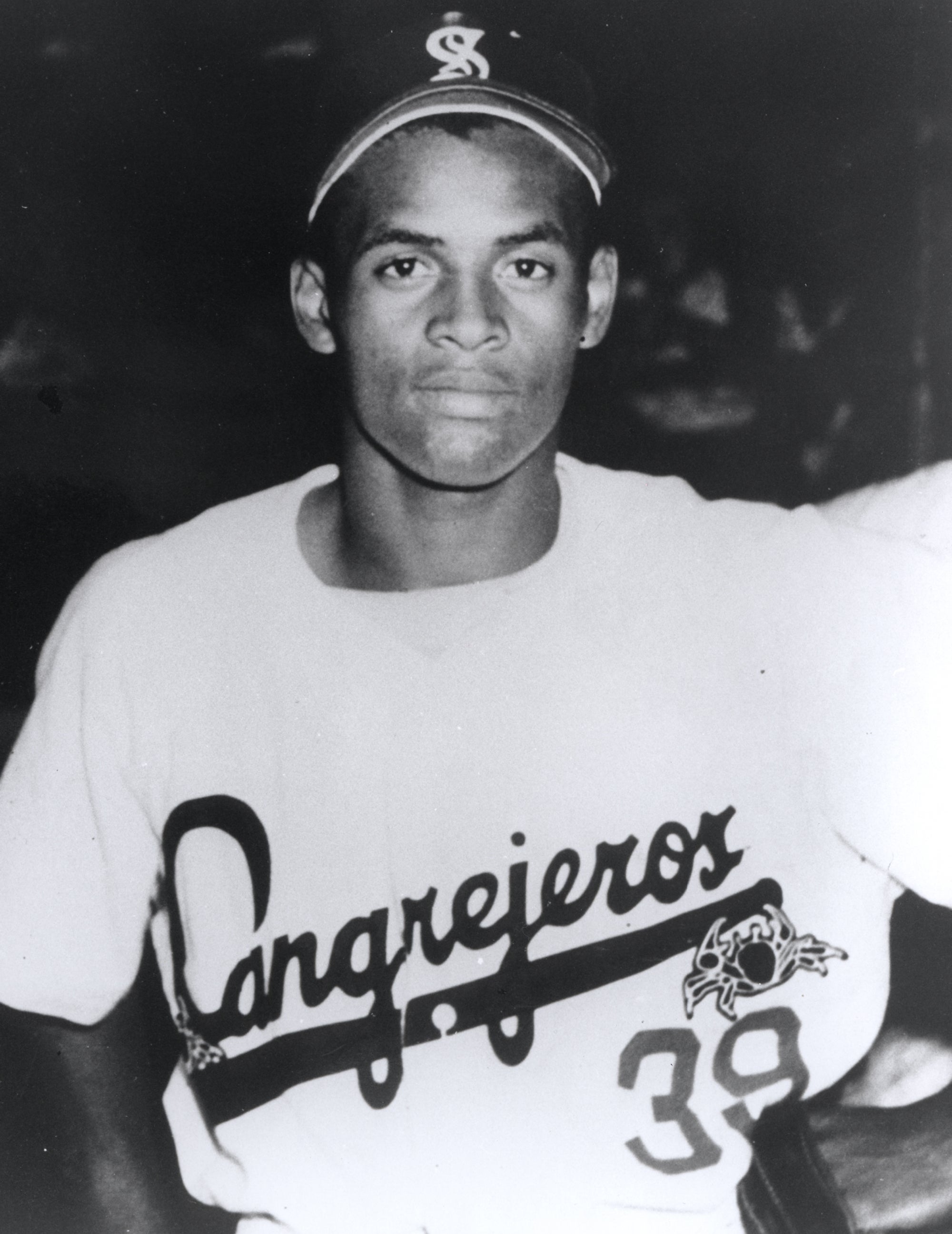

Clemente’s lone minor league season put him on a path to Pittsburgh

Roberto Clemente’s destiny was shaped as a youngster in Puerto Rico

Clemente’s remarkable life explored throughout ’21

Clemente overcame societal barriers en route to superstardom

Clemente’s lone minor league season put him on a path to Pittsburgh