- Home

- Our Stories

- Clemente overcame societal barriers en route to superstardom

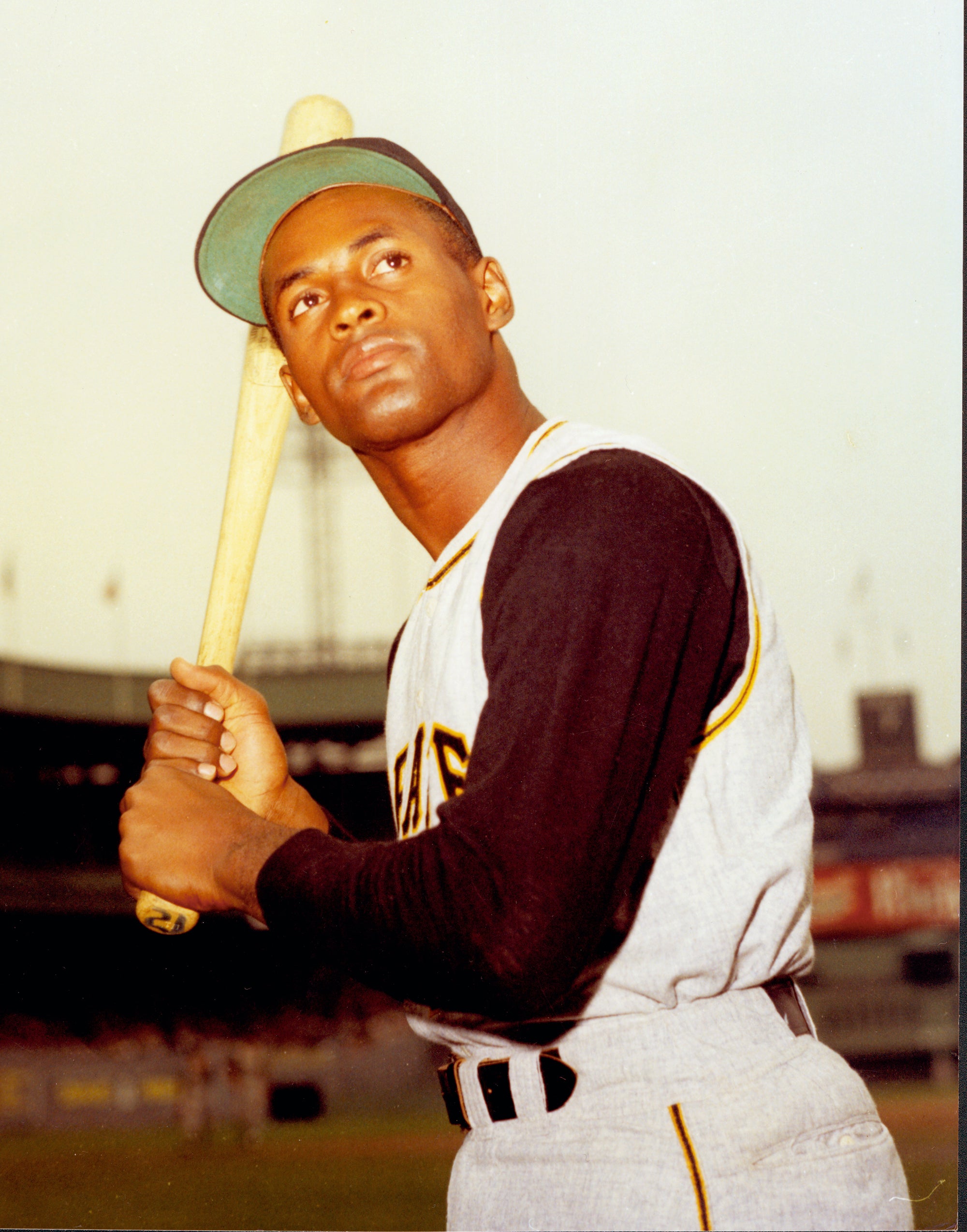

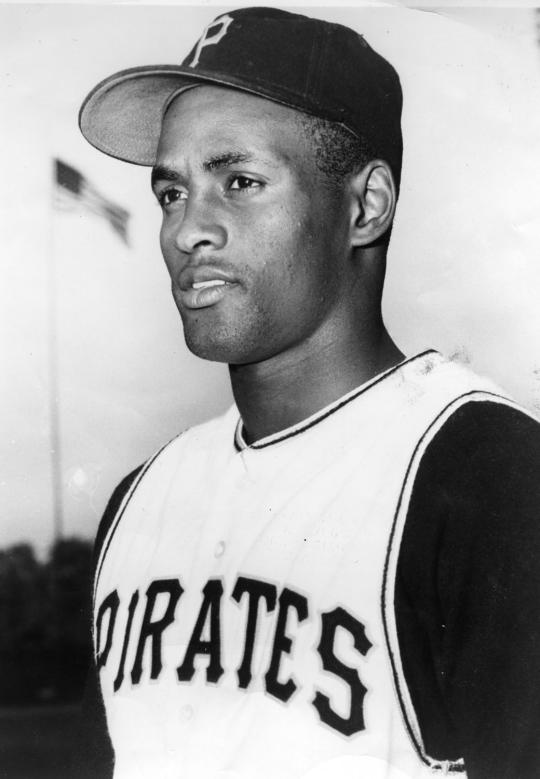

Clemente overcame societal barriers en route to superstardom

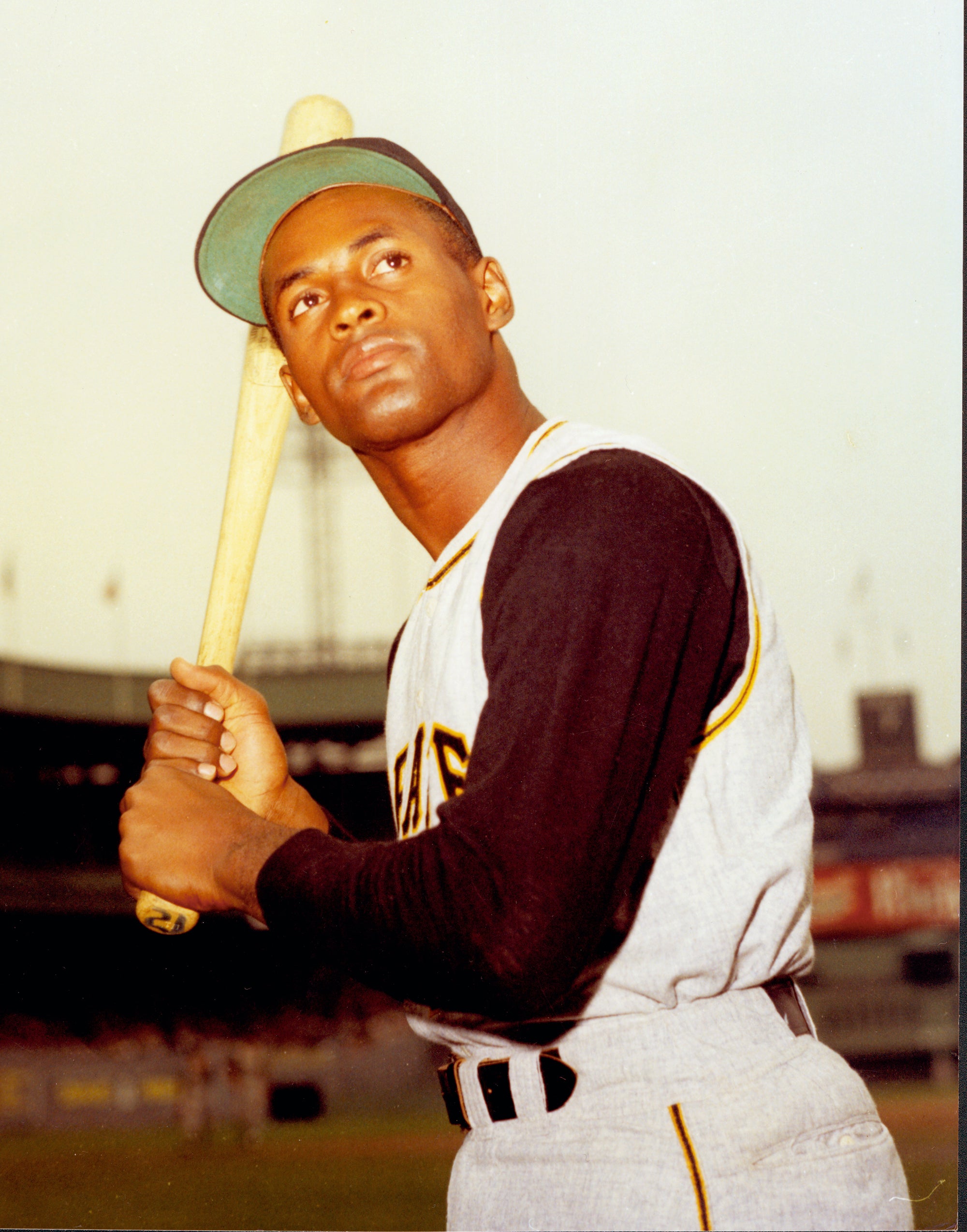

While we think of Roberto Clemente as a true superstar, one of the greatest players of the 1960s, the early years of the decade brought with him a number of difficulties. Some involved his relationships with the media. Others involved his Pittsburgh Pirates teammates.

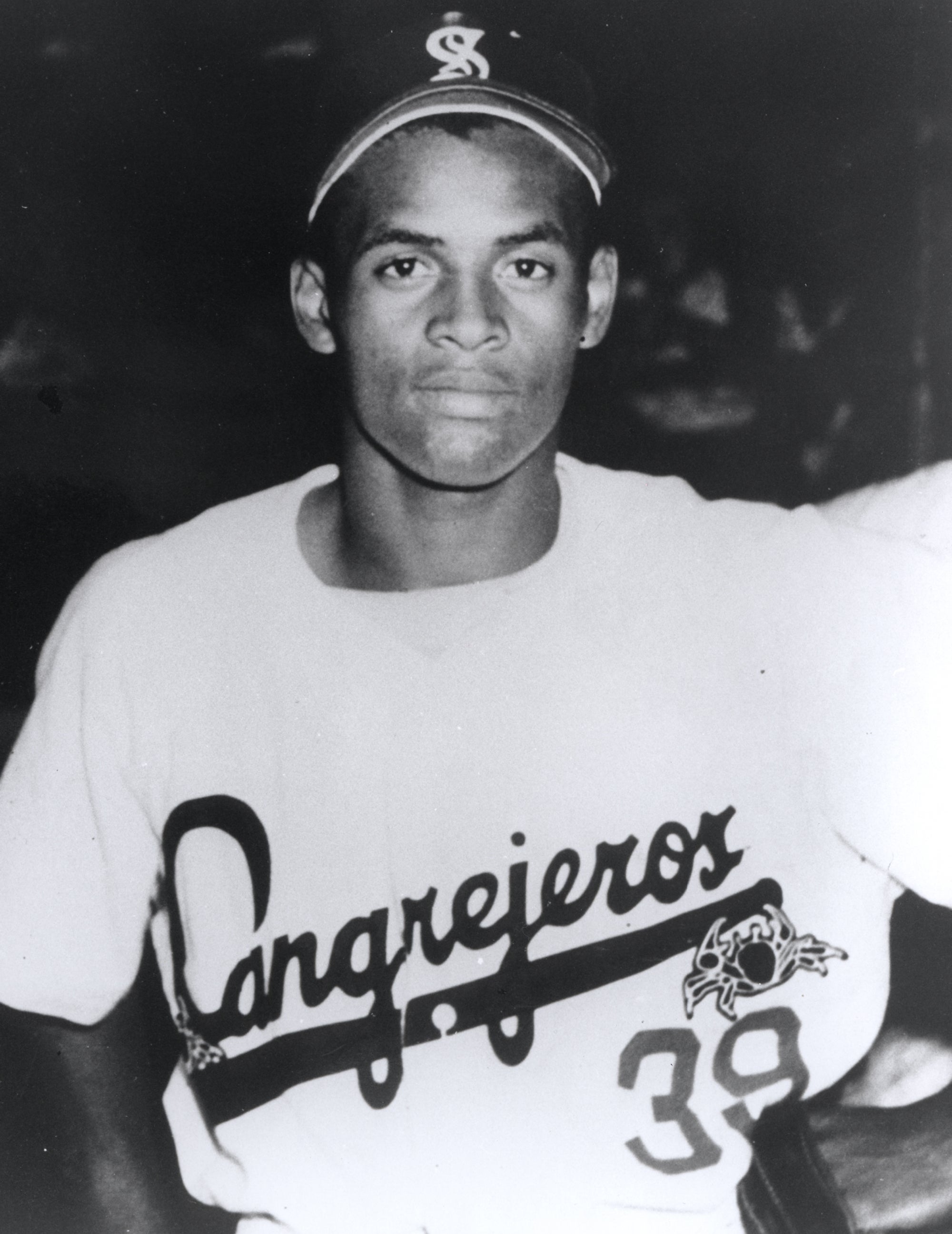

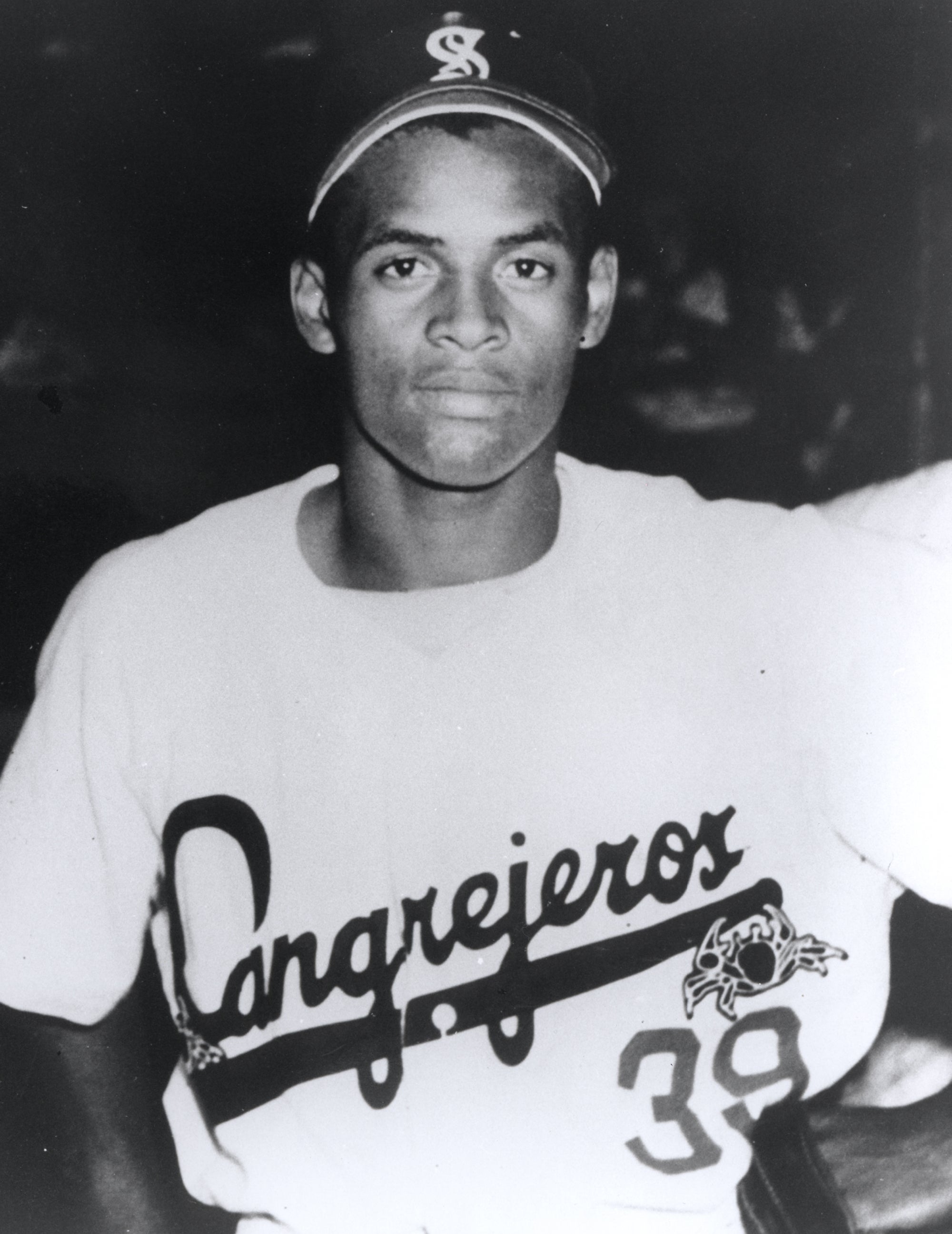

In the early years of his career, Clemente was one of the few Latino or Black players on the Pirates. He was a man who felt little in common with most of his teammates. He was also quiet and reserved, and did not socialize with many of the other Pirates after games. The young Clemente was not yet the spirited team leader and spokesman that we would come to know.

“He was sort of an outsider on the team. He didn’t mix well with the older players,” said Roy McHugh, a venerable Pittsburgh writer who worked for the Pittsburgh Press for parts of five decades. “After (Dick) Groat and (Don) Hoak and some of the others left Pittsburgh, and Clemente became the acknowledged team leader, then the new players looked up to Clemente and the whole atmosphere changed.” With the Pirates also adding more Latino players throughout the 1960s, Clemente would become more comfortable in his surroundings, allowing his natural personality and charisma to emerge.

While Clemente’s standing in the clubhouse would change dramatically over the course of the 1960s, another obstacle would prove more difficult to solve: His contentious relationship with the media. Some of the tension stemmed from the 1960 National League MVP Award balloting. Shortly after the Pirates stunned the world by defeating the New York Yankees in the World Series, the league announced the results of the MVP Award voting, which were based on regular season performance. Pirates shortstop Dick Groat, who had batted .325 and played well in the field, won the MVP Award. Clemente, who had batted .314 with 16 home runs and 94 RBI during the regular season, finished eighth in the balloting.

Clemente harbored no resentment toward Groat and understood why the veteran shortstop won the award. No, Clemente’s complaint had everything to do with finishing eighth in the balloting. He considered it an insult. At the very least, Clemente felt that he deserved a higher place in the voting. When asked about his low finish, Clemente cited “political reasons,” which were code words for his belief that racism against Latino ballplayers had a played a part in the writers’ thinking process.

“He was convinced that it was due to that,” says Luis Mayoral, the longtime writer, broadcaster, executive, and friend to Clemente. “To the day of his death, he was convinced of that.”

Angered by his low finish in the balloting, Clemente chose not to wear his 1960 world championship ring when it was given to him in 1961. Instead, he would start wearing another ring, an All-Star Game ring that came to him in midsummer of ‘61.

The MVP voting snub only made Clemente more motivated to play well in 1961. (And that he did, batting .351 to win the first of his four batting titles.) But his tense relations with the media persisted. During the 1962 season, a question from a reporter left Clemente feeling like he was being set up to criticize a teammate. “One of the sportswriters came in [to the clubhouse],” said Nellie King, a former Pirates pitcher who became a broadcaster with the club. “He said to Roberto, ‘You know, Bob Friend just can’t beat the Giants and the Dodgers. The only teams he can beat are the Mets and the Cubs.’

“Instead of diplomatically trying to sidestep the question, Clemente put the writer on the spot. ‘Why are you talking [over] here, talking to me?’ Clemente said. ‘Bob Friend is over there. You can go tell him [yourself].’”

Clemente decided to carry his point further. As King explained, Clemente walked over to Friend, and while pointing to the writer, said to Friend, “ ‘Bob, he does not think you can beat the good teams, you can only beat the bad teams.’”

Clemente’s demonstration angered the writer, who felt embarrassed, but Roberto had made his point clearly to the writer and the rest of the assembled media: If you have something to say to someone, tell him directly. Don’t expect me to knock a teammate.

Another practice of the media also upset Clemente. It did not involve his teammates, but rather had to do with his heritage and ethnicity. A number of writers and broadcasters insisted on calling Clemente “Bob” or “Bobby,” instead of his given name of Roberto. Even Clemente’s baseball cards listed him as “Bob Clemente,” a practice that persisted through the 1969 Topps set. Clemente did not like this practice, an effort at Americanizing him. He felt that it was disrespectful to his Puerto Rican and Latino heritage. When members of the media interviewed him and called him Bob or Bobby directly, he would correct them. “My name is Roberto Clemente,” he said repeatedly. In spite of his complaints, the practice of referring to Clemente as Bob, especially in print, would continue throughout the 1960s.

And then there was the writers’ tendency to quote Clemente and other Latino players phonetically, emphasizing their Latino accents in newspaper and magazine stories. When Clemente would say a word like “this,” it would sometimes be printed as “deez.” Or a word like “give” would be spelled out as “geev.” Clemente felt that by overemphasizing his Spanish accent throughout their published stories, writers were attempting to make him – and other Latino ballplayers – look foolish. While writers tended to do this with Latino players, they rarely quoted ballplayers with heavy southern accents in a similar way.

“It makes him sound like he’s dumb,” Nellie King once said in complaining about the practice. “And you know he was a very intelligent man… I don’t know why the media did that. It sure made him seem less than intelligent. I mean, how would you like to go to Puerto Rico, [speak Spanish], and have guys quote you the way you sound?” It was a practice that some writers continued as late as 1971, nearly to the end of Clemente’s career.

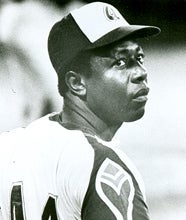

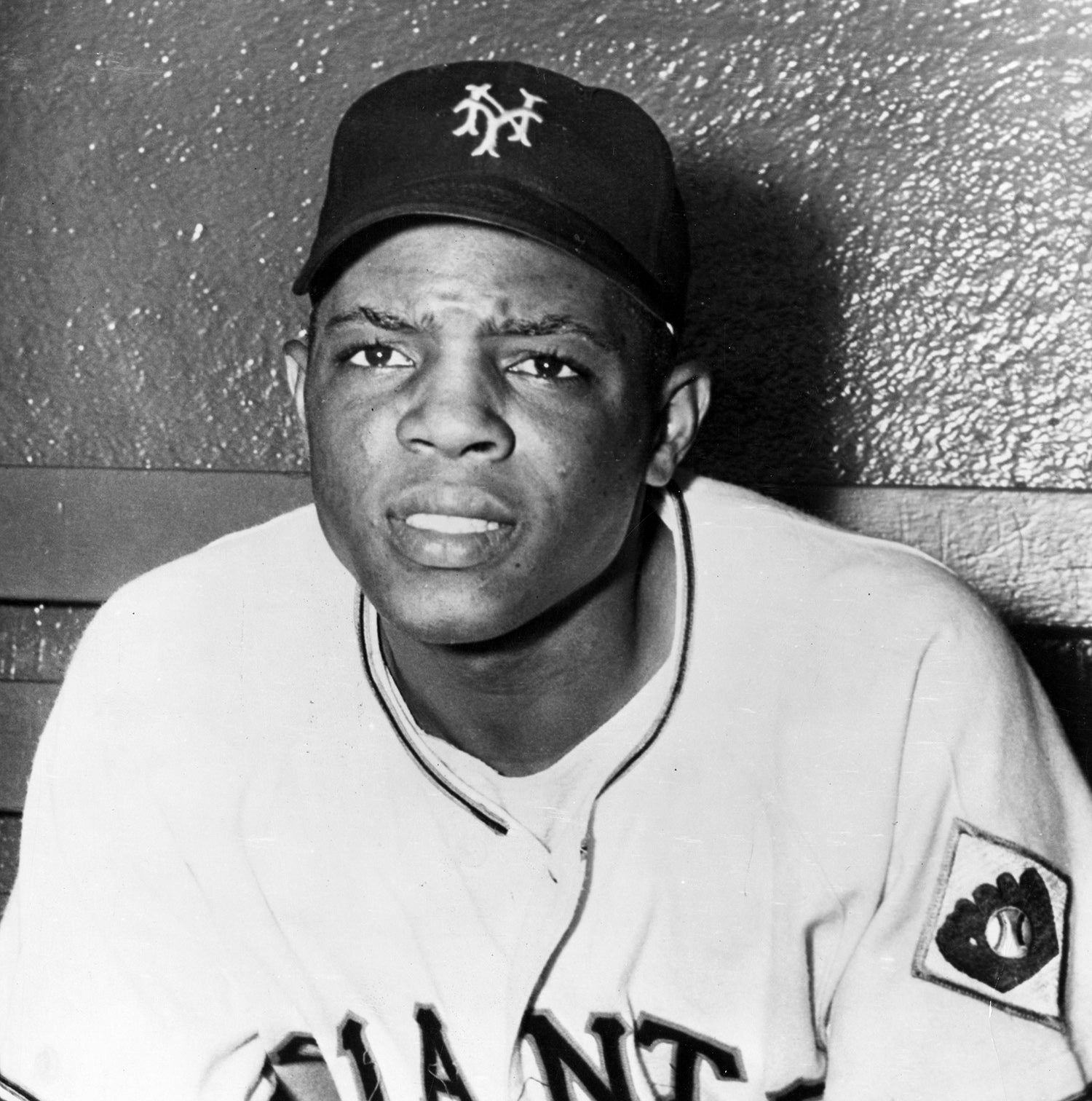

For Clemente, it was just another in a series of roadblocks that he faced during the 1960s. Somehow, he pushed aside those problems, using them as motivation to become a better and more refined player. Over the course of the decade, he would win four batting titles and a much-desired MVP Award. By the end of the 1960s, there was little doubt that Clemente had become one of the game’s superstar outfielders, a player mentioned in the same conversation as the likes of Aaron and Kaline and Mays and Robinson.

All that was left to achieve was another world championship, one that would come in 1971.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Clemente’s remarkable life explored throughout ’21

Clemente’s legacy transcends mere sport

Roberto Clemente’s destiny was shaped as a youngster in Puerto Rico

Clemente’s lone minor league season put him on a path to Pittsburgh

Clemente’s remarkable life explored throughout ’21

Clemente’s legacy transcends mere sport

Roberto Clemente’s destiny was shaped as a youngster in Puerto Rico