- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps Dave LaRoche

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Dave LaRoche

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

You can gauge a little bit about the age of a fan, and what generation he or she comes from, by using certain names in baseball history.

Say the name “LaRoche” to younger fans, and they will almost certainly turn to thoughts of Adam LaRoche, the now retired first baseman who played for the Chicago White Sox, Washington Nationals, and the Atlanta Braves, among other teams. But say the name “LaRoche” to a fan who is 50 or older, like me, and thoughts will gravitate to the father of Adam, former big league reliever Dave LaRoche.

If we continue the theme of word association, the name of Dave LaRoche conjures up images of blooper or “eephus” pitches. All these years later, more than three decades after he retired from pitching, the blooper pitch is what we seem to best remember about LaRoche. In a way, that’s a good thing, because the pitch is fun to watch, almost comical in nature, and brings immediate smiles to our faces. In another way, it’s somewhat unfortunate, because Dave LaRoche assembled a fine career that encompassed far more than a gimmick pitch he threw a few times in the early 1980s.

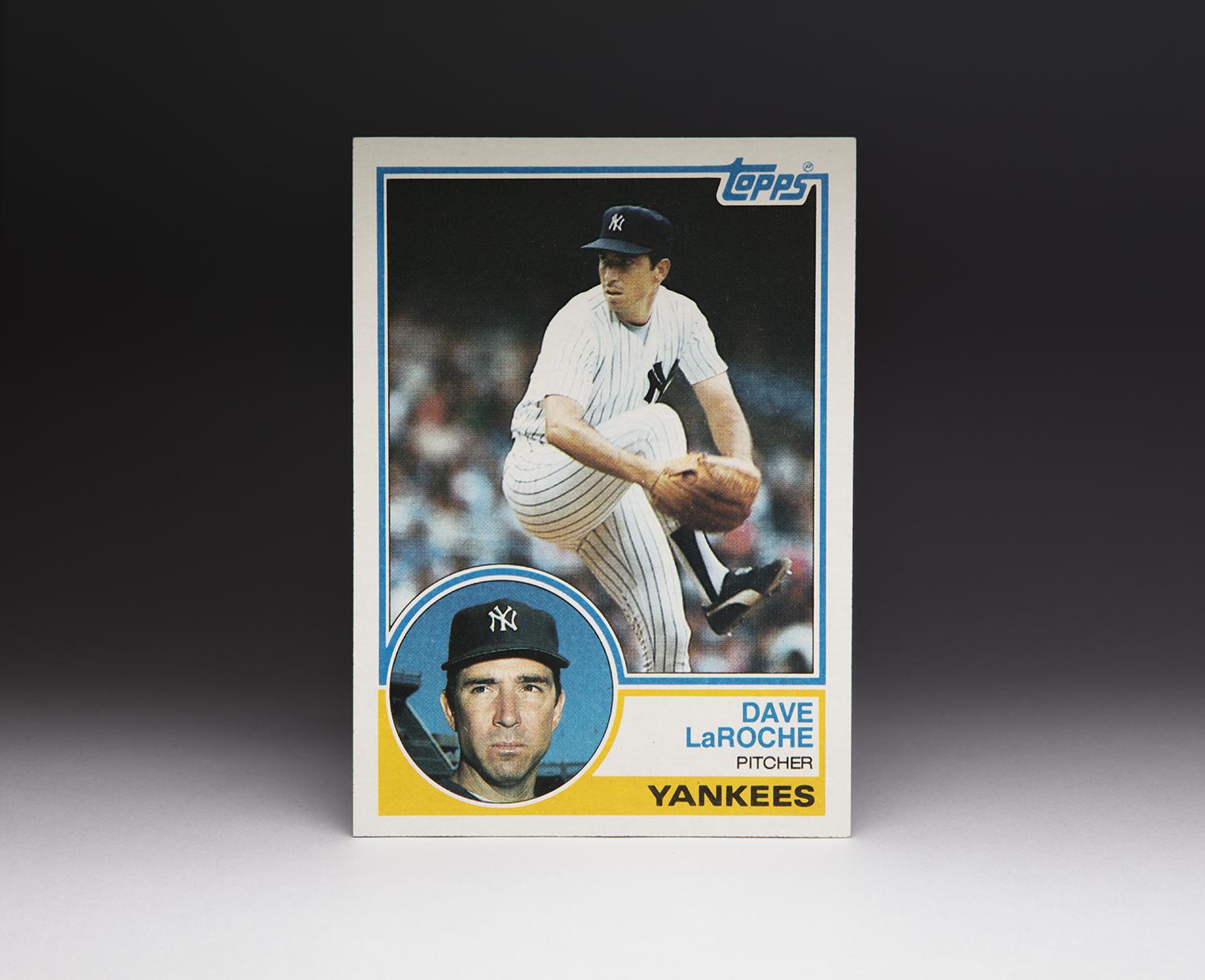

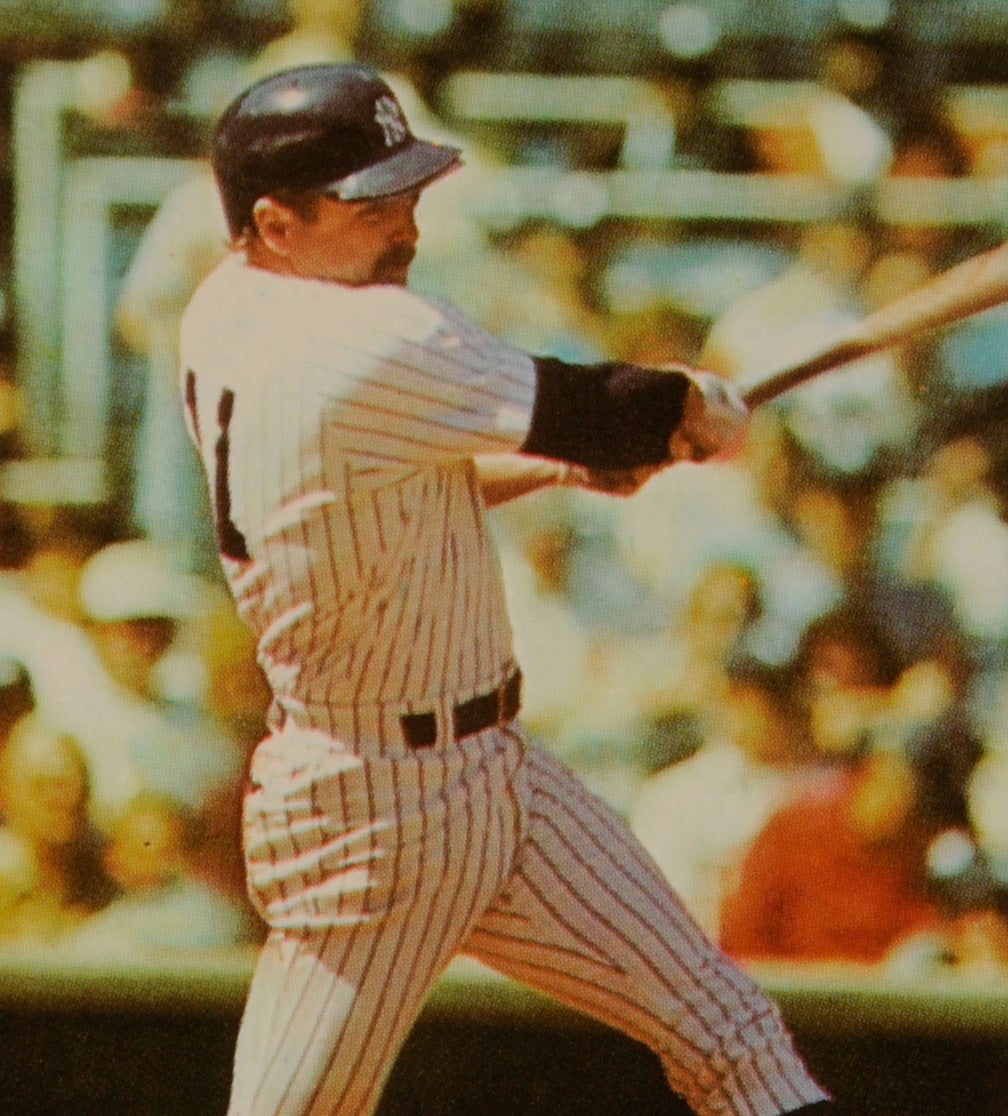

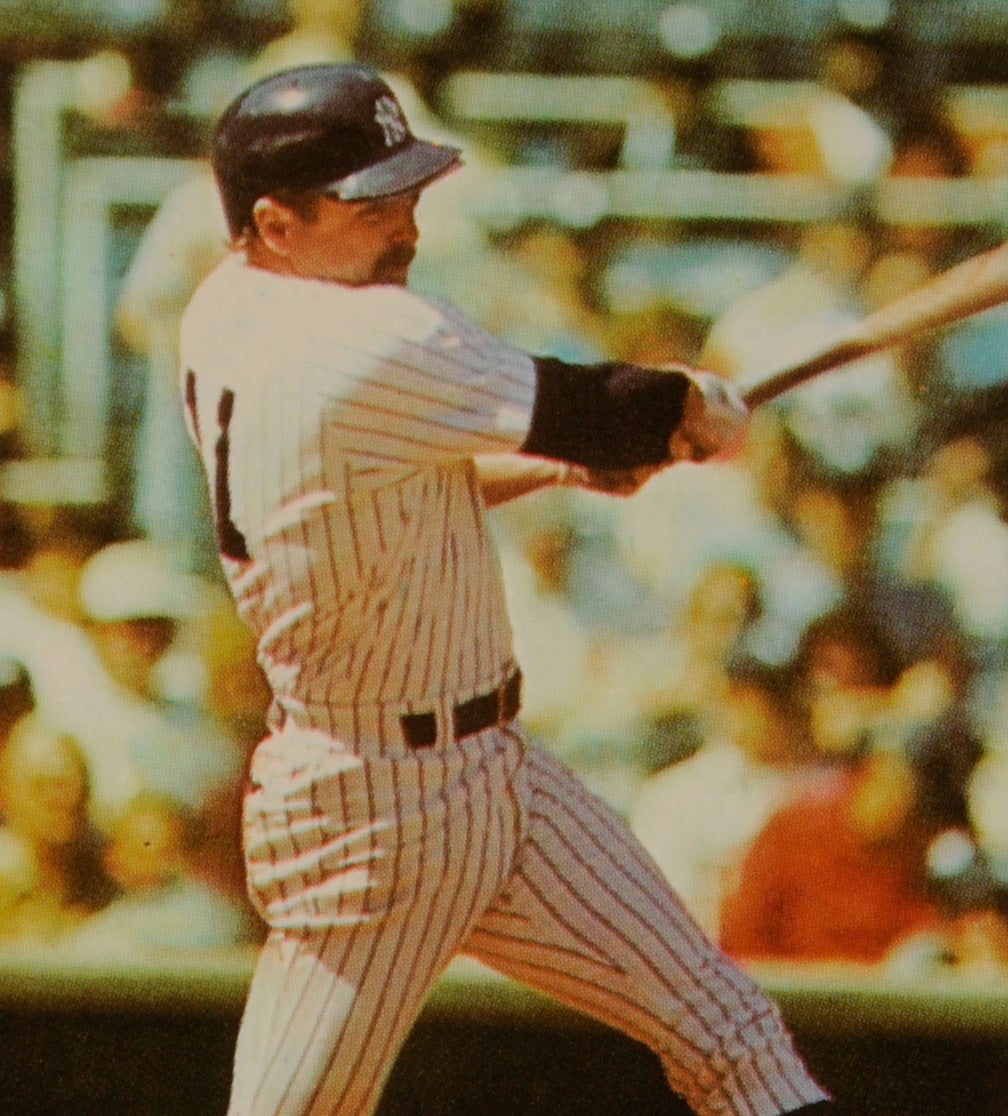

In 1983, Topps put out what turned out to be the final baseball card of LaRoche’s career. In this case, Topps saved the best for last. First off, the 1983 set is a good one to begin with, featuring clear photography, a nice design, and the added bonus of two pictures being featured on the front of each card. Second, the Topps photographer, in taking this picture during the second incarnation of Yankee Stadium, has captured LaRoche perfectly. This is exactly how I remember LaRoche, looking lean in his New York Yankees pinstripes, with that distinctive pitching motion: His back slightly hunched and his right knee tucked up in between his hands. I watched that motion many times in the early 1980s, and thanks to this card, can easily relive it in my mind again and again.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

As intriguing as the LaRoche card might be, there is much more to him than his late-career tenure with the Yankees. By this stage, he was a soft-tossing middle reliever. At one time, he was one of the game’s best left-handed relievers, a hard thrower who could close out games with the best of the American League’s top firemen.

For LaRoche, his pitching journey began many years earlier. But his intriguing backstory goes back further, to his days growing up in Colorado Springs. Of Mexican descent, he was actually born “David Garcia,” but decided to change his name because of teasing from other children in school. So at the age of seven, he formally changed his last name to LaRoche, adopting the last name of his stepfather. For years, people within the game believed that LaRoche was French, but he later admitted that he had no French ancestry whatsoever. LaRoche didn’t publicly reveal his original name until the spring of 1978, when it so happened that his manager with the Indians, in a strange coincidence, shared the same name with him: Dave Garcia.

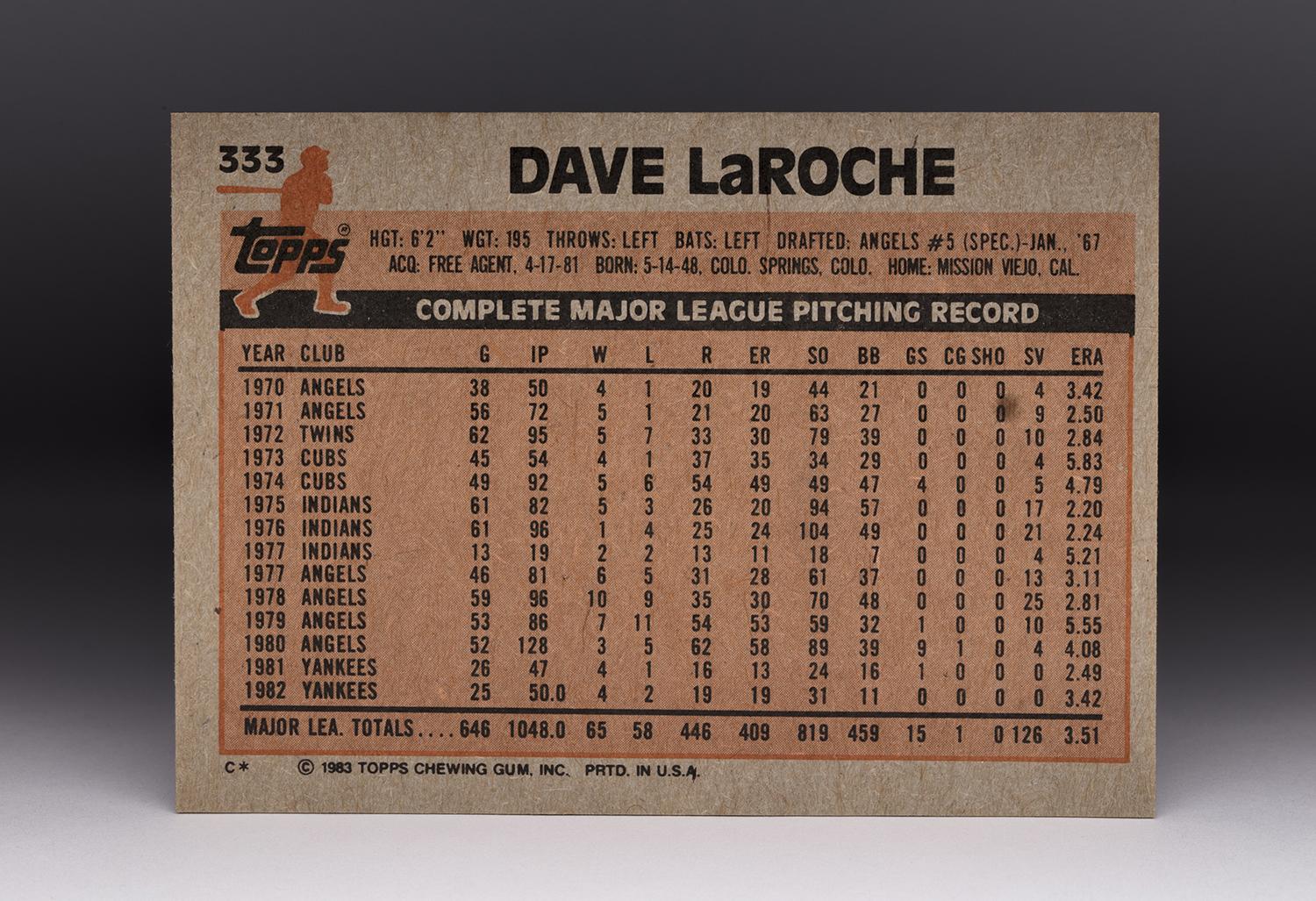

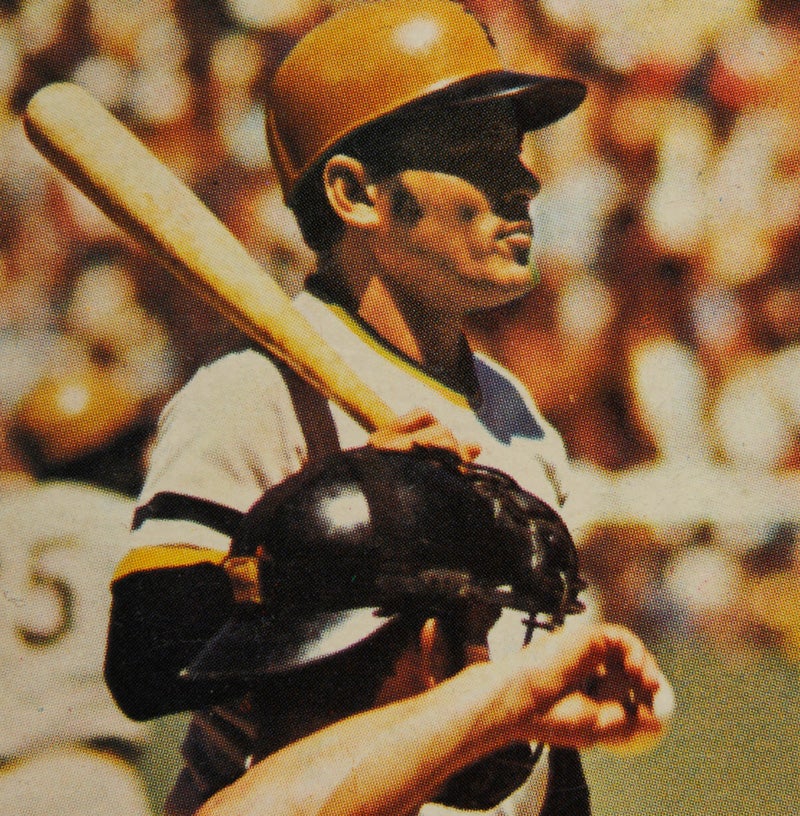

After being drafted by the Angels as an outfielder in 1967, LaRoche switched to pitching in 1968. Two years after making the transition from the outfield to the mound, LaRoche arrived in California. He pitched well as a rookie, striking out 44 batters in 49 innings and putting up an ERA of 3.44. He fared even better as a sophomore, lowering his ERA to 2.50 and sharing fireman duties with right-hander Lloyd Allen.

As well as LaRoche pitched in his first two seasons, he carried a high trade value. In desperate need of some middle infield help, the Angels gave in to the temptation of trading LaRoche, sending him to the Minnesota Twins for veteran shortstop Leo Cardenas. The trade was short-sighted; Cardenas, a fine player, turned out to be past his prime and lasted only one year with the Angels.

LaRoche would last only one year with Minnesota, as well, but not because of how he pitched. Splitting relief ace chores with sidewinding right-hander Wayne Granger, LaRoche saved 10 games and struck out 79 batters in 95 innings. Off the field, LaRoche and the Twins experienced difficulties. LaRoche ruffled feathers, developing a reputation as something of an agitator. As the Twins’ player representative, he frequently filed complaints against the organization. He also clashed with teammates, including one of the team’s stars, who eventually challenged him to a fight.

The Twins’ front office decided to cut LaRoche loose. In what turned out to be another short-sighted deal, the Twins sent him packing that winter, trading him to the Chicago Cubs for three right-handed pitchers, including veteran starter Bill Hands.

Unfortunately, LaRoche did not pitch well for the Cubs, gaining no advantage against National League hitters who had never seen him before. At first, he was bothered by tendinitis. Then the Cubs’ coaching staff urged him to throw his fastball as hard as he could, challenging him to match the velocity of Nolan Ryan. That approach did not work. After two subpar seasons in Chicago, including a temporary demotion to minor league Wichita, the Cubs dealt him, marking his third trade in four seasons. This time, the deal saw him staying in the Midwest, but heading back to the American League, to the Cleveland Indians for right-hander Milt Wilcox.

The trade to the Indians reunited LaRoche with his former Angels teammate, Jeff Torborg. Now the Indians’ bullpen coach, Torborg understood LaRoche’s mechanics better than just about anyone. Torborg realized that LaRoche needed to throw from an over-the-top motion, which allowed his power fastball to remain high in the strike zone. The Indians soon slotted the hard-throwing left-hander into the closer’s role and watched him strike out 94 batters in 82 innings. He was a bit wild, issuing 57 walks, but allowed only 61 hits and posted an ERA of 2.19. At the end of the season, the team’s beat writers voted LaRoche “Man of the Year” honors.

In 1976, LaRoche put up nearly identical numbers, but with an increased workload, as he pitched 96 innings. He also lowered his walk total. Then came the contentious spring of 1977. LaRoche and Indians general manager Phil Seghi failed to come to an agreement on a long-term contract. LaRoche expressed bitterness toward Seghi, accusing him at one point of failing to negotiate.

The Indians feared that LaRoche would leave at season’s end, cashing in on free agency. Rather than take a chance on losing him for nothing in October, the Indians included LaRoche in a trade with the Angels, sending him and minor league hurler Dave Schuler to California for lefty reliever Sid Monge, first baseman/outfielder Bruce Bochte, and a large sum of cash.

LaRoche was now back with his original major league team, but he noticed a far different atmosphere than what he had seen during his first tenure with the Angels.

"When I was here in ’71, [manager] Lefty Phillips was having problems with Alex Johnson,” LaRoche recalled in an interview with Angels beat writer Dick Miller. “There were problems with things other than baseball.” One of those problems had involved a clash of teammates, specifically Johnson and Chico Ruiz, a utility infielder. At one point, Ruiz threated Johnson by brandishing a gun at his locker. "

By 1978, the Angels had a far more harmonious clubhouse. LaRoche himself had changed, becoming more at ease with the industry and gaining a reputation as somewhat of a prankster. On the field, LaRoche gave the Angels exactly what they needed: A competent closer. Prior to his arrival, the Angels’ bullpen had become known as “The Arson Squad.” LaRoche changed all of that, saving 13 games and bringing stability to the back of the California bullpen.

In 1978, LaRoche put together arguably his finest season. Pitching 95 innings, he saved 25 games and won 10 decisions. American League beat writers though enough of his performance to give him some back-of-the-ballot support in the Most Valuable Player voting.

That turned out to be the high point of his Angels tenure. LaRoche struggled badly the next two seasons, perhaps because he had averaged nearly 100 innings per year over a three-year-stretch. At one point, the Angels used him as a spot starter, but the experiment didn’t help the situation. LaRoche also clashed with Jim Fregosi, the Angels’ manager, who had taken him out of the bullpen against his wishes.

The Angels hoped that LaRoche would bounce back in the spring of 1981, but he continued to struggle, his mechanics becoming completely fouled up. Just before Opening Day, the Angels released him. Two weeks later, he found work with the Yankees, who needed help in the middle innings. Making adjustments in his approach, LaRoche worked on making the transition from power to finesse. He also fully unveiled his blooper/eephus pitch, which reached remarkable heights before sinking fast as it descended toward the strike zone.

The pitch gained prominence on a September night, as the Yankees played host to the Milwaukee Brewers. Bob Lemon, recently hired as manager to replace Gene Michael, summoned LaRoche from the bullpen. Lemon asked LaRoche if he wanted to pitch to slugger Gorman Thomas or walk him intentionally. LaRoche responded by saying that he would try to retire Thomas with his curveball. Little did Lemon know that the LaRoche curveball was actually a pitch that his teammates called “La Lob.”

Much to Thomas’ surprise, the pitch came in at a height of roughly 20 feet before descending. Shocked at what he saw, Thomas took the first pitch. Then LaRoche threw another, Thomas swung hard, and pulled it foul down the third base line. LaRoche threw another, which Thomas attempted to bunt, but the ball went foul. After spotting a fastball outside of the strike zone, LaRoche returned to the blooper pitch. Once again, Thomas swung hard, completely missing the pitch and nearly corkscrewing himself into the ground.

LaRoche was not the first Yankee to have ever thrown a blooper pitch. That honor belonged to Steve Hamilton, a reliever from the 1960s who featured what he called the “Folly Floater.” Going back further, the eephus pitch dated back to the 1940s, when Rip Sewell threw it for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

LaRoche had actually debuted his trick pitch one year earlier, while closing out his final season with the Angels. He came up with the idea while pitching slo-pitch softball during the offseason. But no one seemed to notice the blooper ball until he unveiled the pitch with the Yankees and struck out Thomas. Scouts, using radar guns, clocked the pitch at 28 miles per hour. Fans loved it. So did the Yankee infielders. Whenever LaRoche threw the pitch, Willie Randolph, Bucky Dent, and Graig Nettles giggled into their gloves, attempting to hide their laughter from the opposing hitter.

“La Lob” overshadowed LaRoche’s fine work as a middle innings man for the Yankees. In 47 games, he put up a 2.49 ERA. He continued to pitch creditably through the 1982 season, but also had to endure several demotions to Triple-A Columbus. LaRoche became a vaunted member of the “Columbus Shuttle,” making a total of four round trips between Columbus and New York during a stretch of three months.

The highlight of his 1982 season came on Aug. 6, when the Yankees hosted the Texas Rangers. With two strikes, LaRoche unleashed his eephus pitch on slugging first baseman Lamar Johnson, who swung so hard that he lost his balance. Several of Johnson’s Ranger teammates began to laugh so hard that they ran from the dugout into the showers, so as to hide themselves from the already embarrassed first baseman.

In 1983, LaRoche failed to make the Yankees’ Opening Day roster, largely because he did not have a guaranteed contract and because the Yankees had five other left-handers on their roster. LaRoche agreed to go back to the minor leagues, where he pitched decently, and earned a recall to New York in August. On Aug. 23, he pitched poorly in a relief outing against the Oakland A’s. Even though it was only one game, the Yankees decided to release the 35-year-old veteran, ending his career.

It did not take long for LaRoche to move on after the end of his pitching days. He found work as a college coach, before eventually returning to Organized Ball as a pitching coach. After putting in time with a number of organizations, including the Yankees and Toronto Blue Jays, LaRoche joined the New York Mets. In his last job, he served as the pitching coach for their Class A affiliate, the Brooklyn Cyclones, until stepping aside at the end of the 2015 season.

LaRoche is 68 now and enjoying retirement in Kansas. Given that his trademark pitch barely reached 30 miles an hour on the radar gun, I imagine that even in retirement, he still might be able to unleash one of those wonderful La Lobs, just for old time’s sake.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

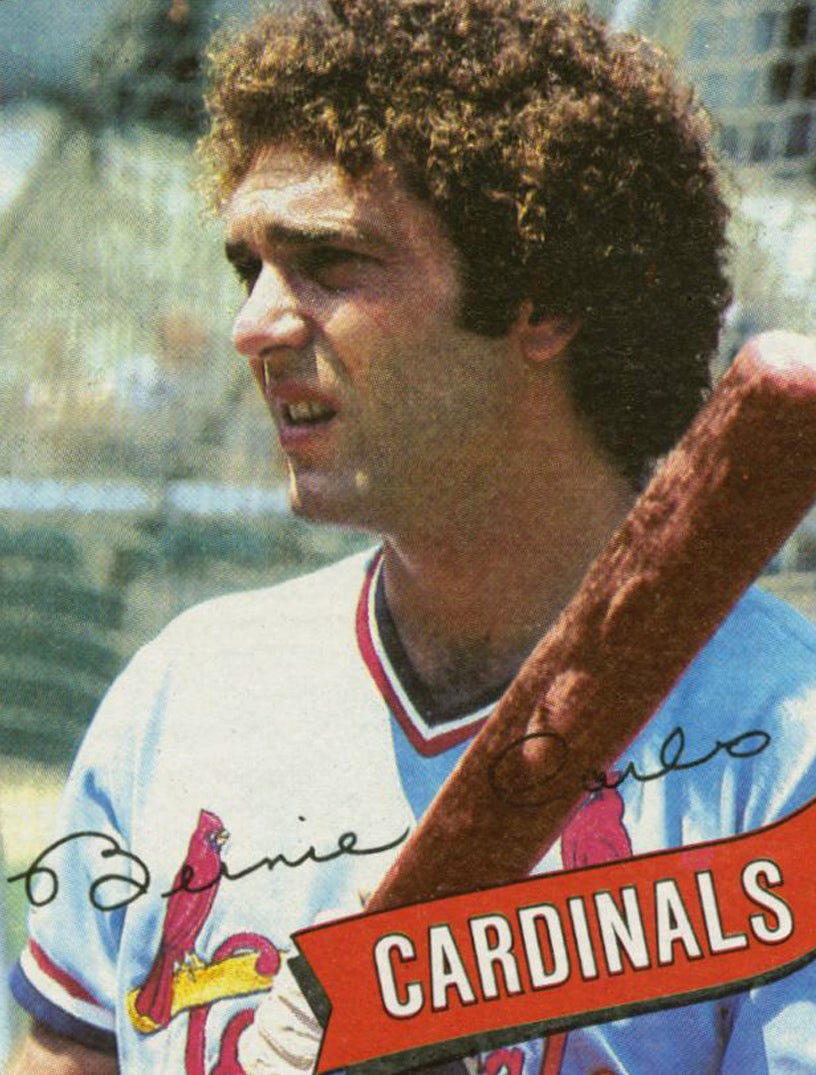

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah