- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1982 Donruss Tim Foli

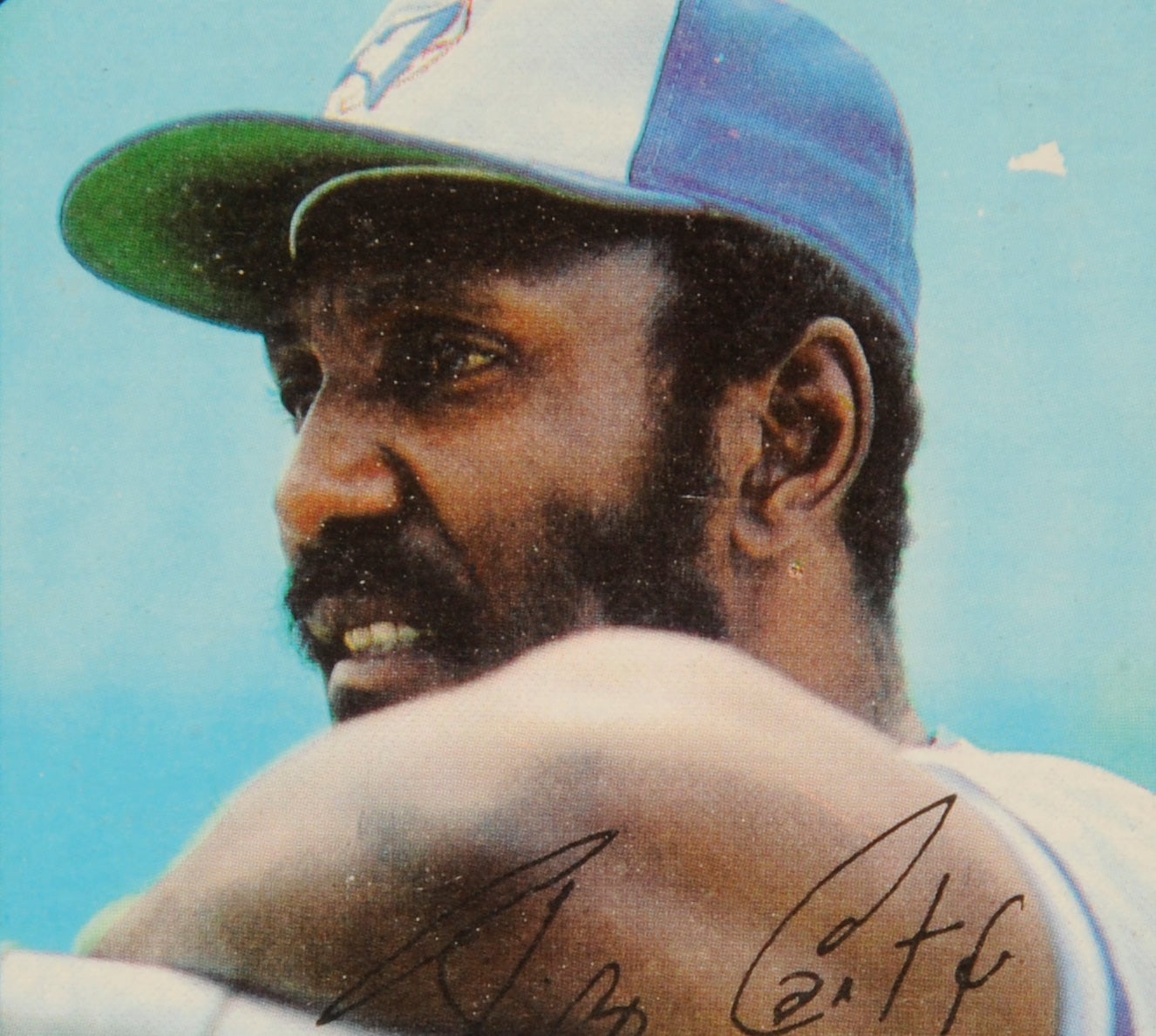

#CardCorner: 1982 Donruss Tim Foli

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

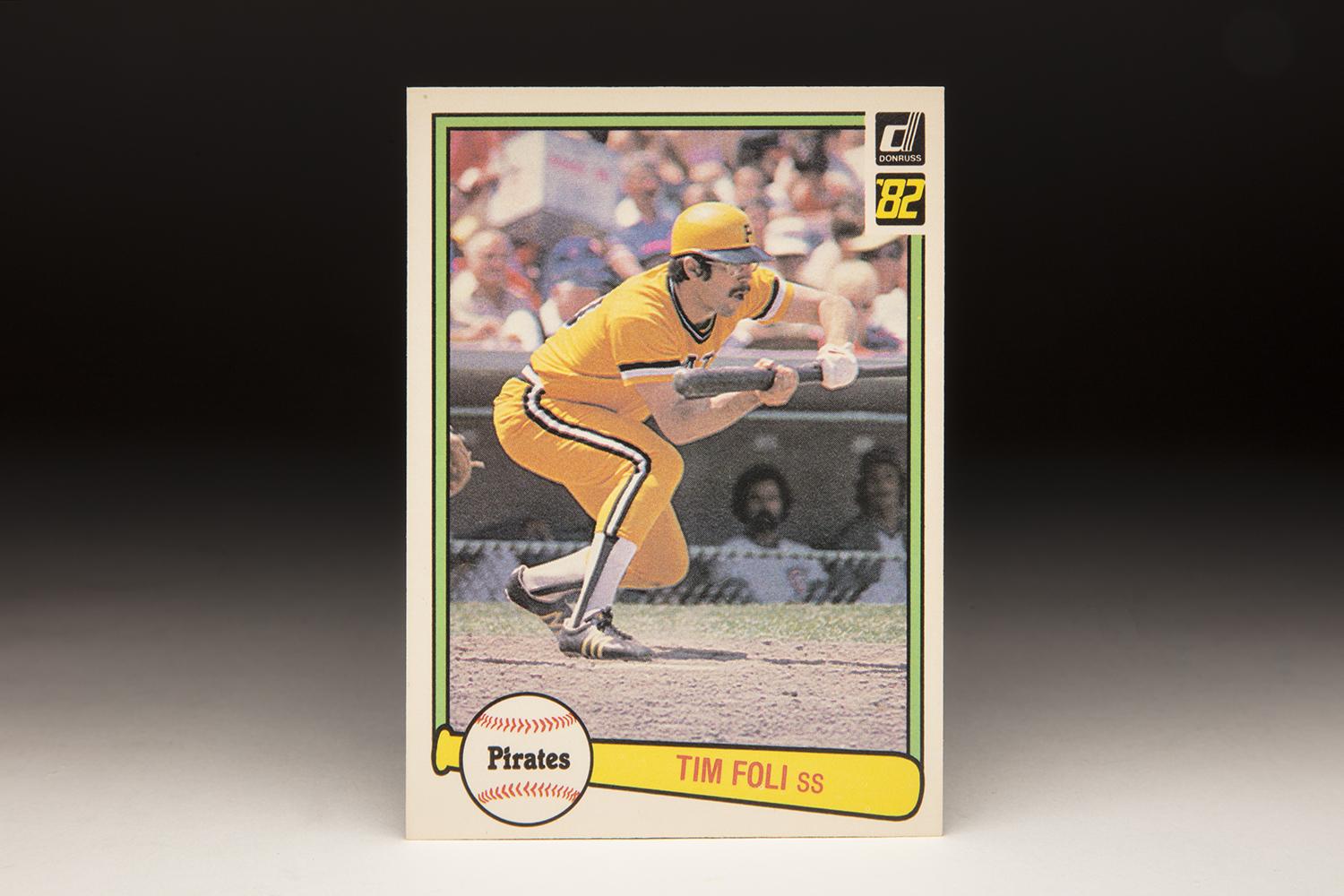

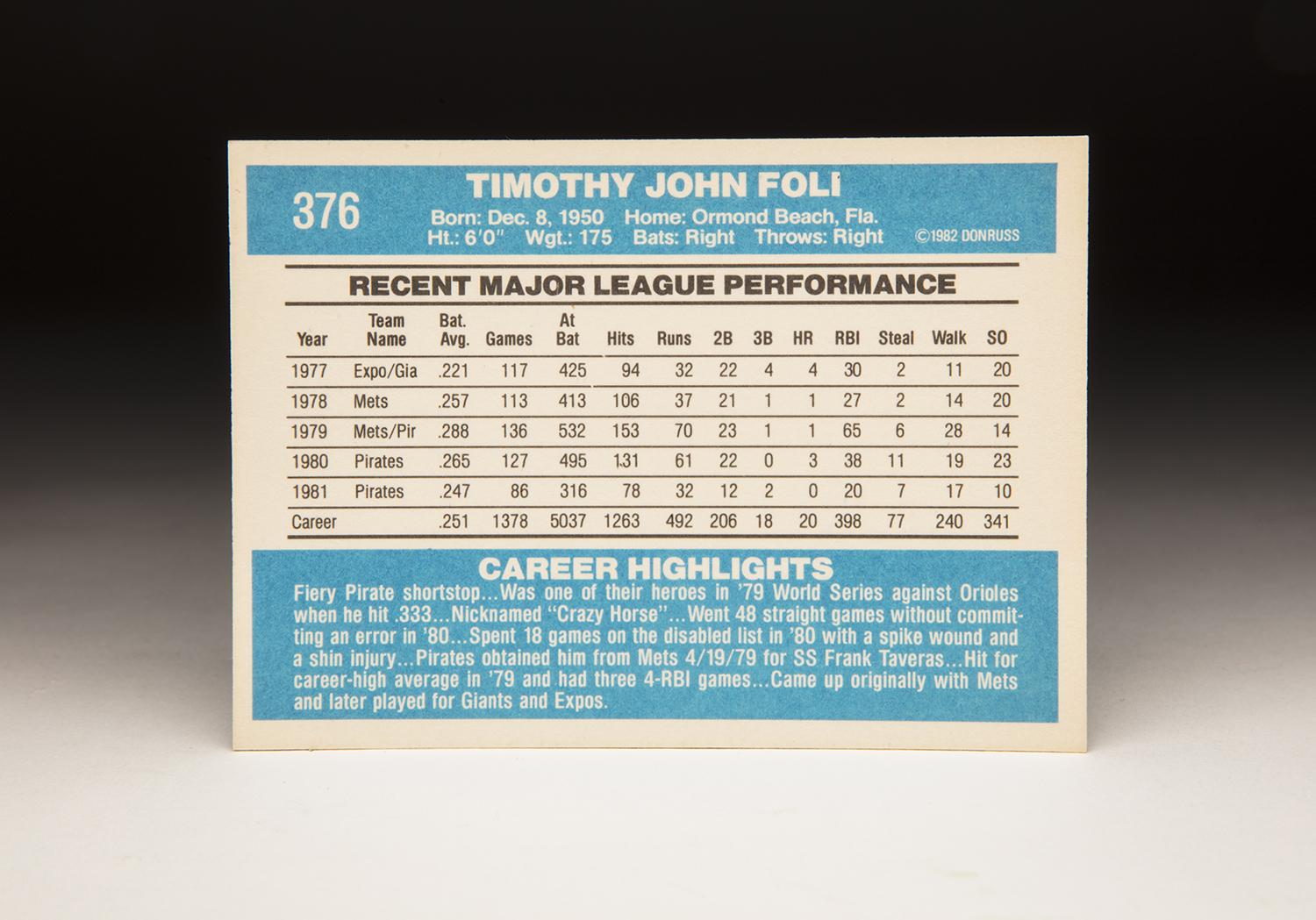

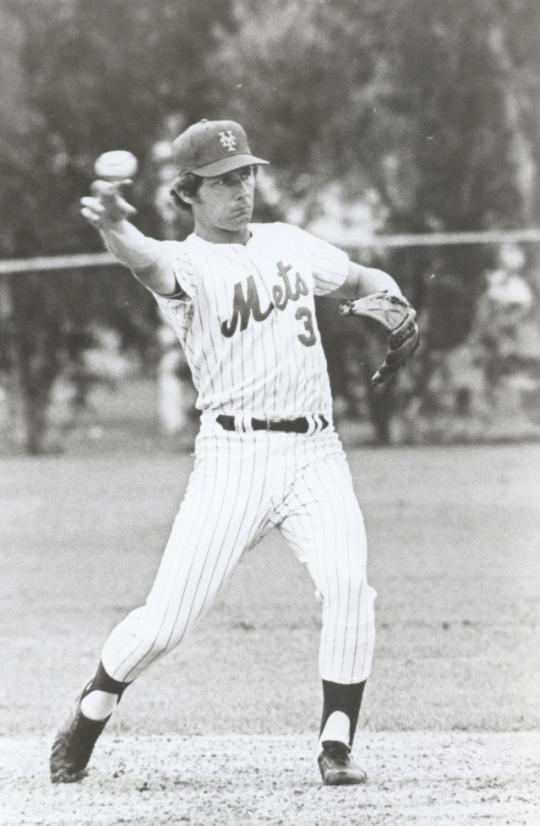

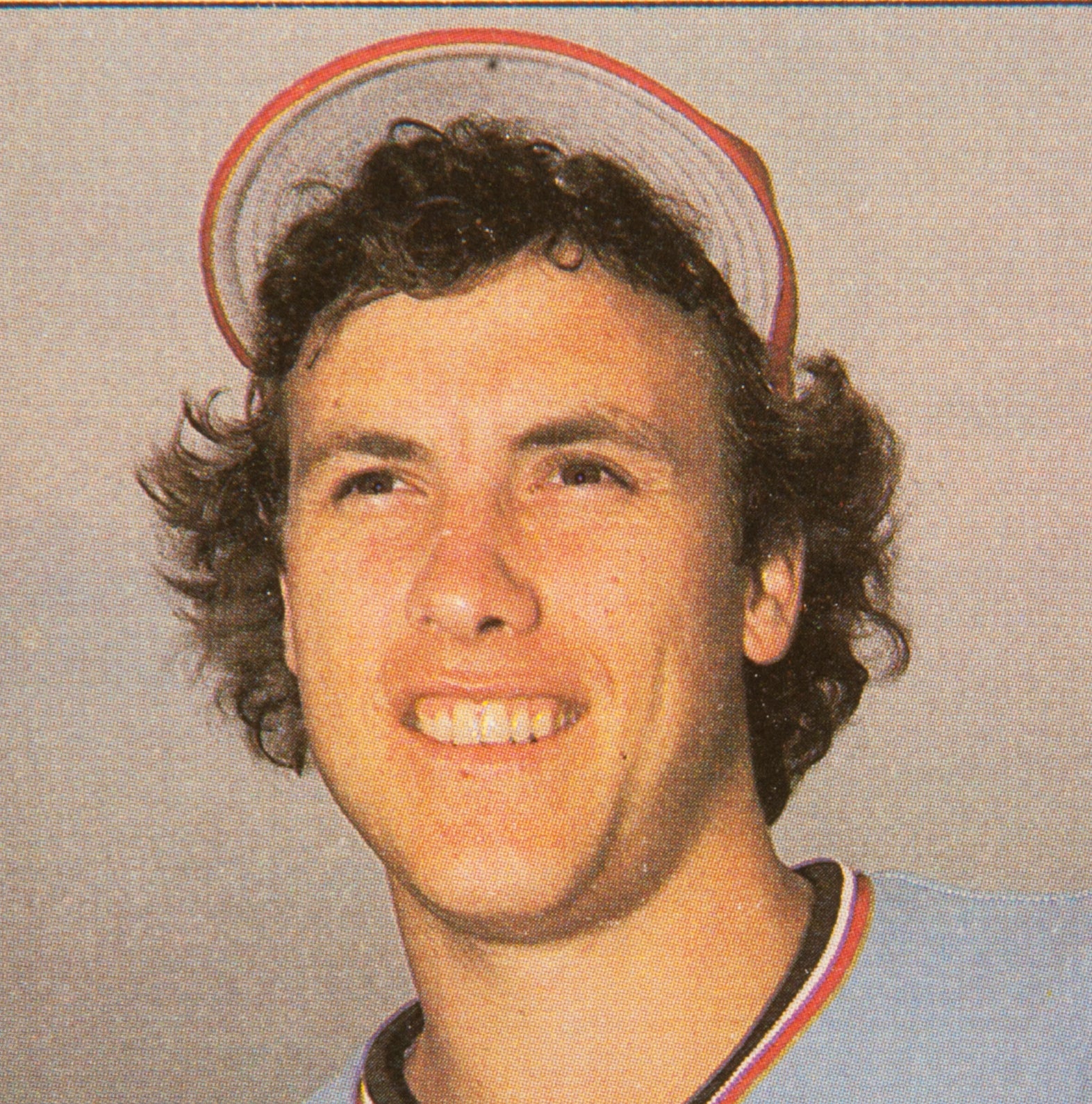

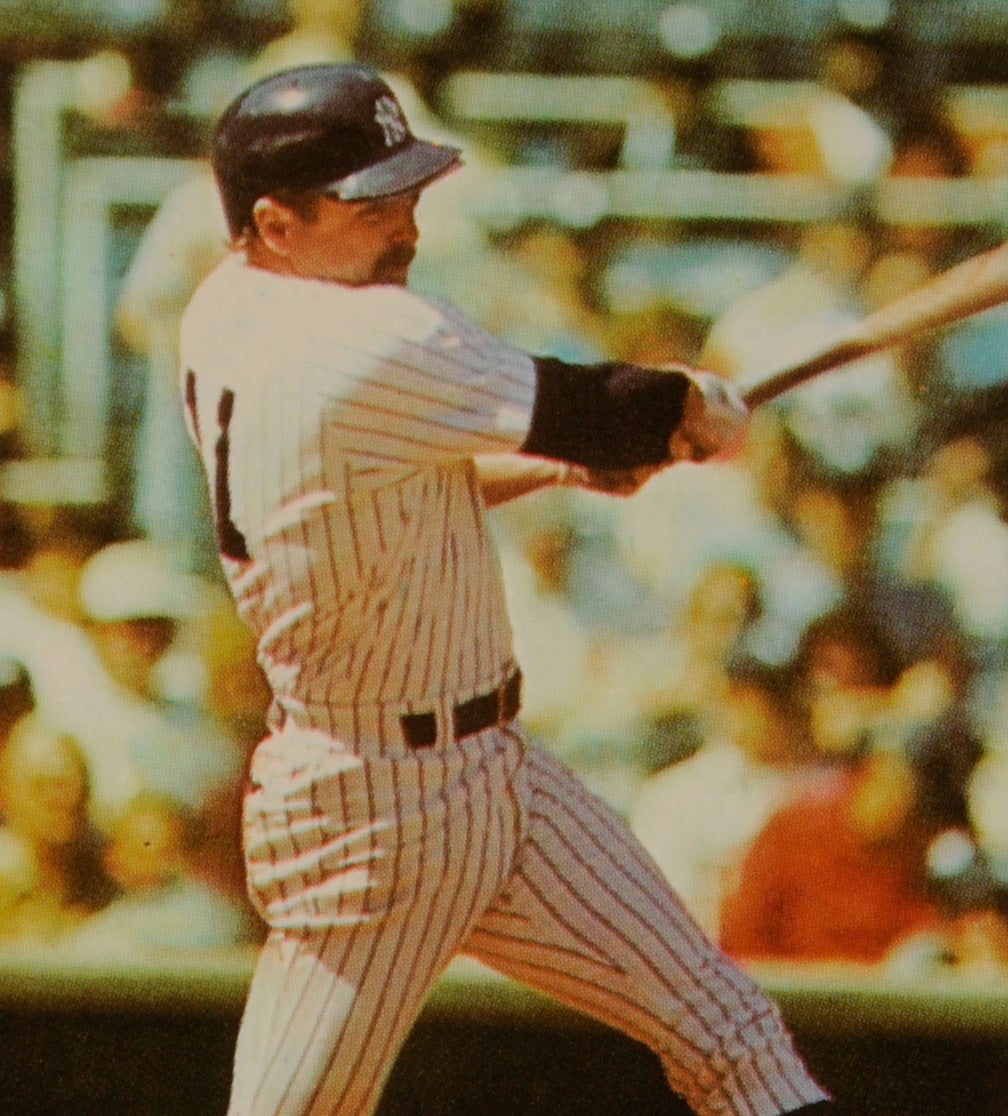

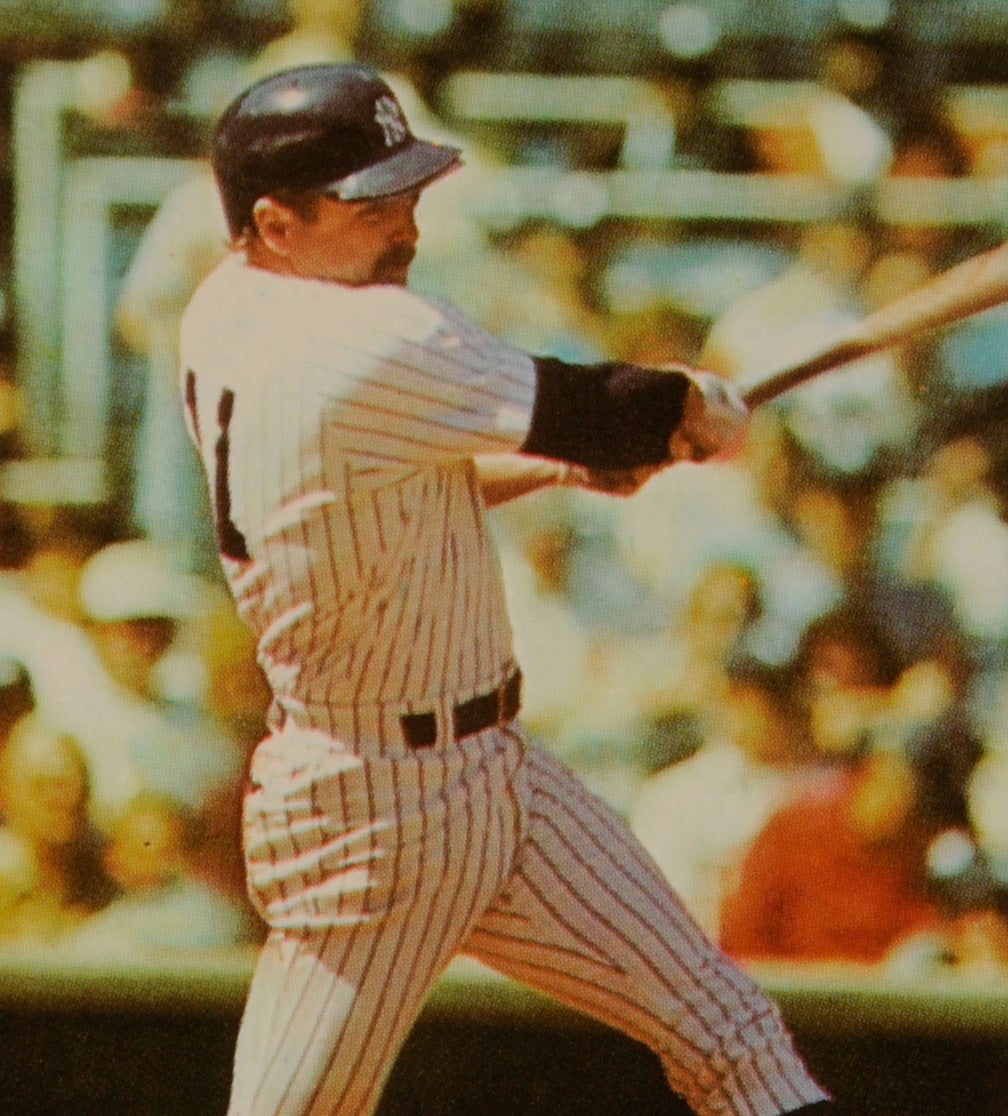

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus, and yes, there was a time when ballplayers looked like this. Tim Foli’s 1982 Donruss card epitomizes the look of the era, from the high stirrups and the tight-fitting pants to the brightly colored gold uniform worn by the Pittsburgh Pirates. Foli’s oversized wire-frame glasses and large, arching mustache (both somewhat visible here) complete the picture of the early 1980s ballplayer.

It is also fitting that the card shows Foli squaring around to bunt during a game at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. Foli was an outstanding bunter, perhaps the best in the game at the time, a player who regularly led the National League in putting down sacrifice bunts. But don’t let Foli’s tendency to lay down bunts fool you. While his offensive game might have been meek and lacking in power, his personality was not.

Nicknamed “Crazy Horse,” Foli developed a reputation as a high-strung individual whose mood could turn explosive. Those who liked him called him “strong” and “fiery,” while others who didn’t care for him described him as “overbearing.” He had a ferocious temper that often put him at odds with umpires and even teammates.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Long before establishing such a reputation, Foli’s professional career began with a degree of acclaim. In 1968, the New York Mets made him the No. 1 overall pick in the amateur draft. Most scouts viewed him as a franchise player, a shortstop who could hit, hit with power, and field. He also played the game hard, never taking a play or an at-bat off, no matter the circumstances of the game.

All of 17, Foli reported to the Rookie League, where he hit .278 with seven stolen bases in 68 games. He started to show some power the following season, when he hit 15 home runs for Visalia of the California League. He also made the league’s all-star team, but began to develop a reputation for high-end intensity. After one game, in which he went hitless in five at-bats, a frustrated Foli returned to the ballpark, camped out at second base, and spent the entire night sleeping on the infield.

In 1970, Foli became the talk of the Mets’ Spring Training camp, but was disappointed when he was sent to Triple-A Tidewater prior to Opening Day. He hit more modestly at Tidewater than he had in the lower minor leagues, batting .261 with six home runs. Still, the Mets regarded him as their shortstop of the future. In September of 1970, they gave him a taste of the major leagues. He appeared in only five games, but gave the Mets reason to be hopeful, hitting .364 in 11 at-bats.

The Mets did have a problem, however. They already featured a highly competent shortstop in Bud Harrelson, an excellent fielder who had been a part of the world championship success of 1969. Wanting to get Foli into the lineup as much as possible, manager Gil Hodges used him as a utility player in 1971. Foli played second base, third base, shortstop, and even center field, showing versatility and athleticism. Conversely, he didn’t hit much. With a .226 batting average and a .281 slugging percentage, Foli’s lack of offense gave the Mets cause for concern.

So too did Foli’s tightly wound personality. It was in 1971 that some of his Mets teammates began to call him Crazy Horse because of the intense way in which he stalked up and down the dugout while the Mets batted. He also developed a habit of telling other players what to do. Some of the veteran Mets resented this practice, especially coming from a rookie.

At one point, Foli tangled with first baseman Ed Kranepool, the team’s elder statesman. Foli became upset when Kranepool refused to throw the ball to him during infield warmups. At the end of the half-inning, a fuming Foli made his way into the Mets’ dugout, where he confronted Kranepool. Within seconds, angry words turned into fisticuffs. The fight didn’t last long, largely because Kranepool outweighed Foli by 25 pounds. Kranepool punched Foli in the face, sending the rookie infielder to the dugout floor.

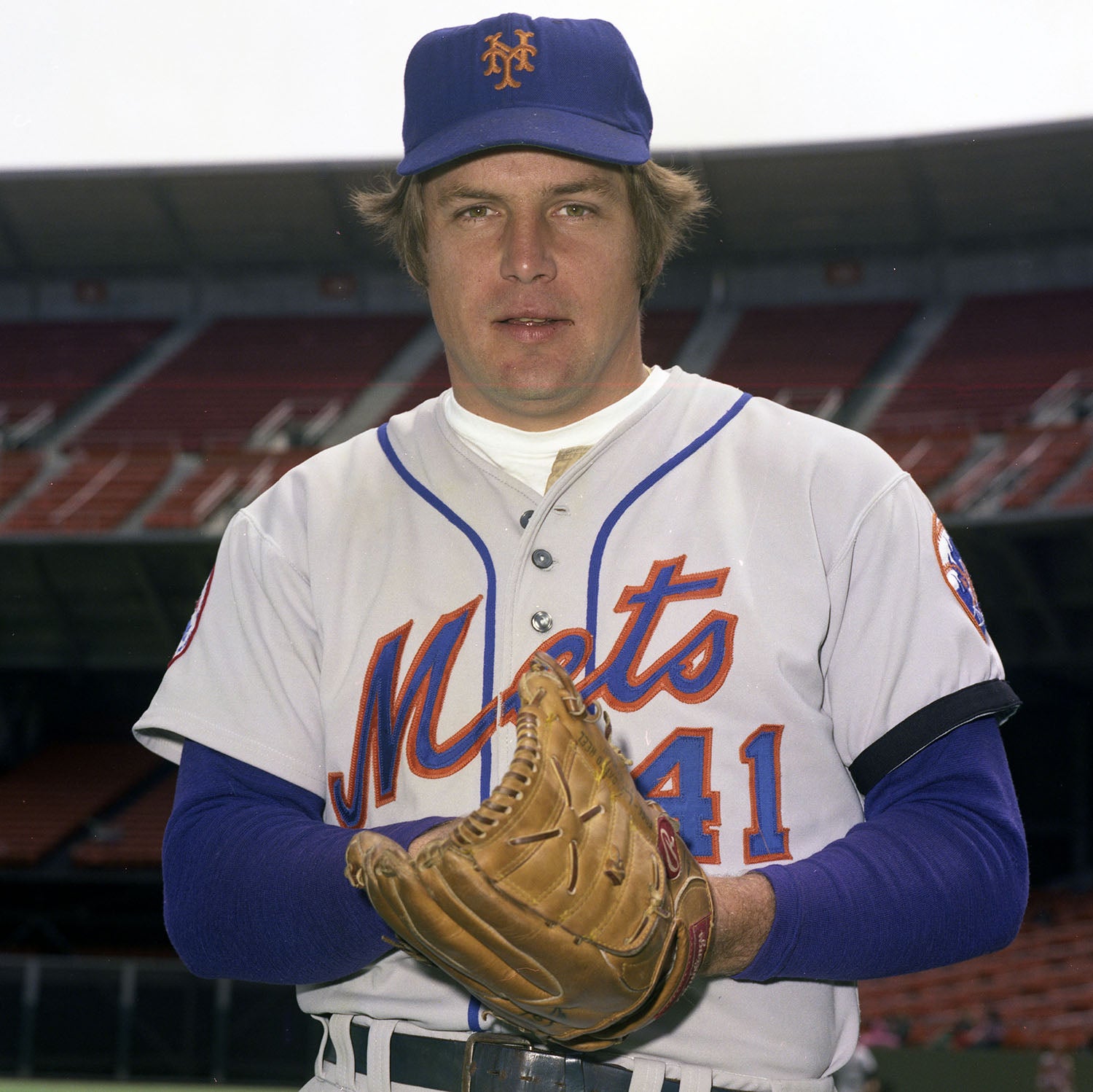

While Foli’s behavior drew the ire of several veteran Mets, he found an ally on the pitching staff, in the form of future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver. “He’s a very aggressive player, but all his actions are aimed in a positive direction,” Seaver told Jack Lang of the Sporting News. “He’s only a kid and he’s learning, but he wants to learn right.”

The following spring, Foli became involved in another confrontation, this time with a member of the Mets’ coaching staff. The dispute, which centered on a misunderstanding over the allocation of hockey tickets given to Mets players, pitted Foli against bullpen coach Joe Pignatano. The two men shouted at each other before throwing punches. The incident resulted in a pair of broken glasses for Foli. Later on, Foli received a reprimand from Hodges.

The incident with Pignatano signaled an upcoming change for Foli and the Mets. On April 5, just before the strike-delayed start of the season, the Mets announced a major trade. The deal packaged Foli with two other young players, first baseman Mike Jorgensen and outfielder Ken Singleton, all of whom went to the Montreal Expos for established star Rusty Staub.

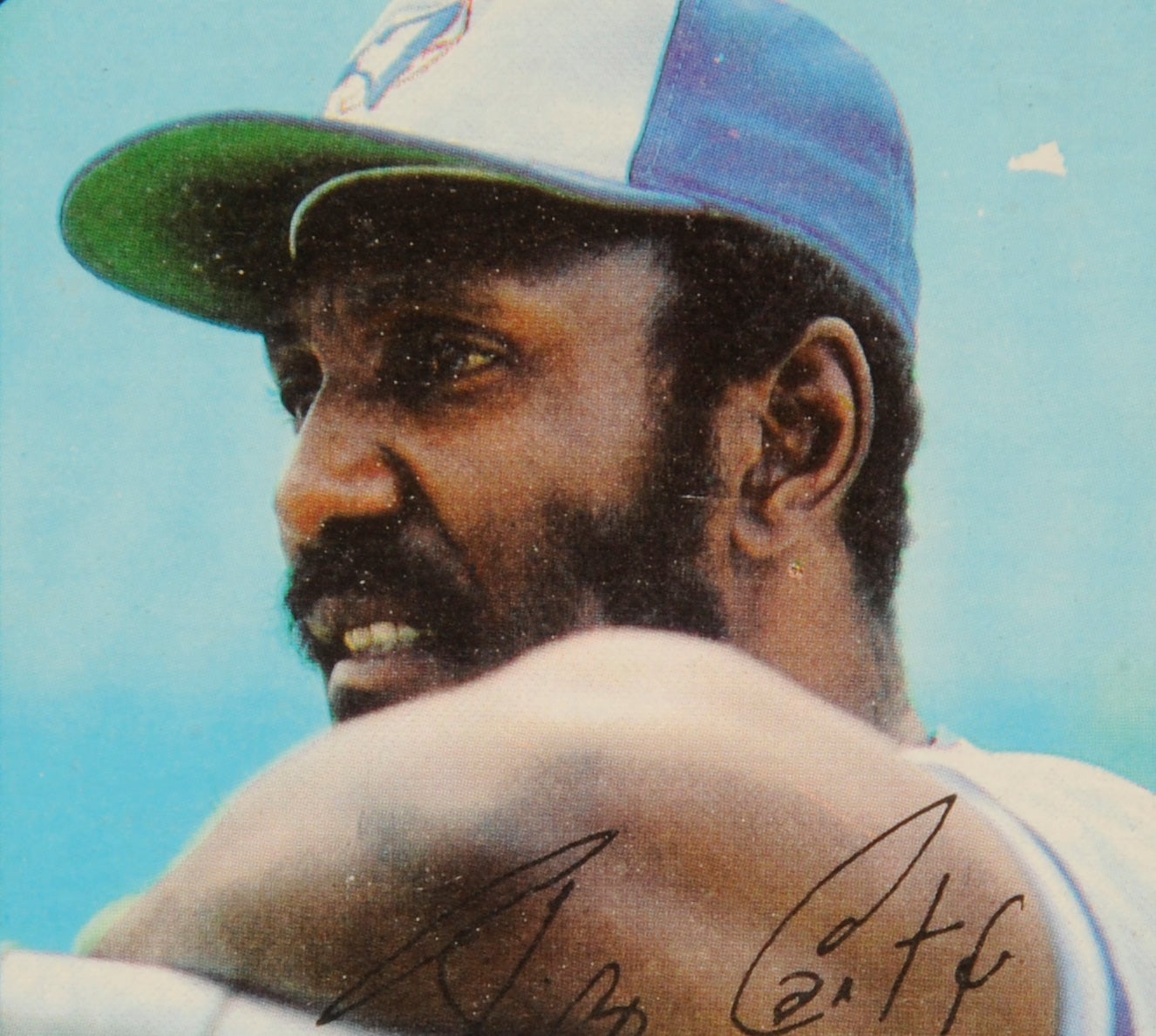

Expos manager Gene Mauch made Foli his starting shortstop. As he had done with the Mets, he continued to lag at the plate in 1972, hitting only .242 with no power. Over the span of five seasons with Montreal, Foli never hit higher than .264 and didn’t draw more than 36 walks in a season. But he did blossom into an outstanding defensive shortstop, a position that he played with range, smoothness, and efficiency.

The Expos liked the defensive stability that Foli brought to the infield, but they bristled at his exchanges with teammates, coaches, managers, and umpires. In May of ‘72, Foli received a three-game suspension for an argument with umpire Dick Stello. And then in 1973, he made physical contact with another umpire, Ken Burkhart, resulting in another three-game ban.

During a tumultuous 1976 season, Foli openly defied the two managers who succeeded Mauch: Karl Kuehl and Charlie Fox. Foli cursed out Kuehl in view of his teammates and later called a press conference where he questioned whether Kuehl should even be managing in the major leagues. Shortly thereafter, the Expos fired Kuehl and replaced him with Fox.

On the final day of the season, Foli refused to sit in the dugout with the rest of his teammates. Instead, he watched the game from the stands in Wrigley Field. Foli’s anger was directed mostly at the Montreal writers, who had chosen not to vote him as the Expos’ player of the year. But the move by Foli clearly embarrassed Fox, who was furious that one of his players had refused to sit with the team.

More trouble came Foli’s way in 1977. He feuded with newly signed free agent and double play partner Dave Cash, in whom the Expos had invested a large sum of money. The Expos regarded the strained relationship as the last straw. They worked out a deal with the San Francisco Giants. In a one-for-one swap, the Expos sent Foli to San Francisco for veteran shortstop Chris Speier.

Exorcized from the Expos, Foli found little consolation in San Francisco. Some of his Giants teammates, noting his frequent fits of anger, began calling him “Rubber Room” behind his back. Knowing that he was not liked in the clubhouse, Foli did not play well for his new team. He batted only .228 and compiled an OPS of just .571. Not surprisingly, the Giants parted ways with Foli. In December, they sold Foli to his original team, the Mets.

By this time, Foli had become legendary for his abilities as a bench jockey. He loved to ride opponents from the dugout, picking up on any perceived weakness. Foli also made it obvious that he disliked umpires. If he felt that an umpire had wronged him early in the game, he carried a grudge until the final out, regardless of the score.

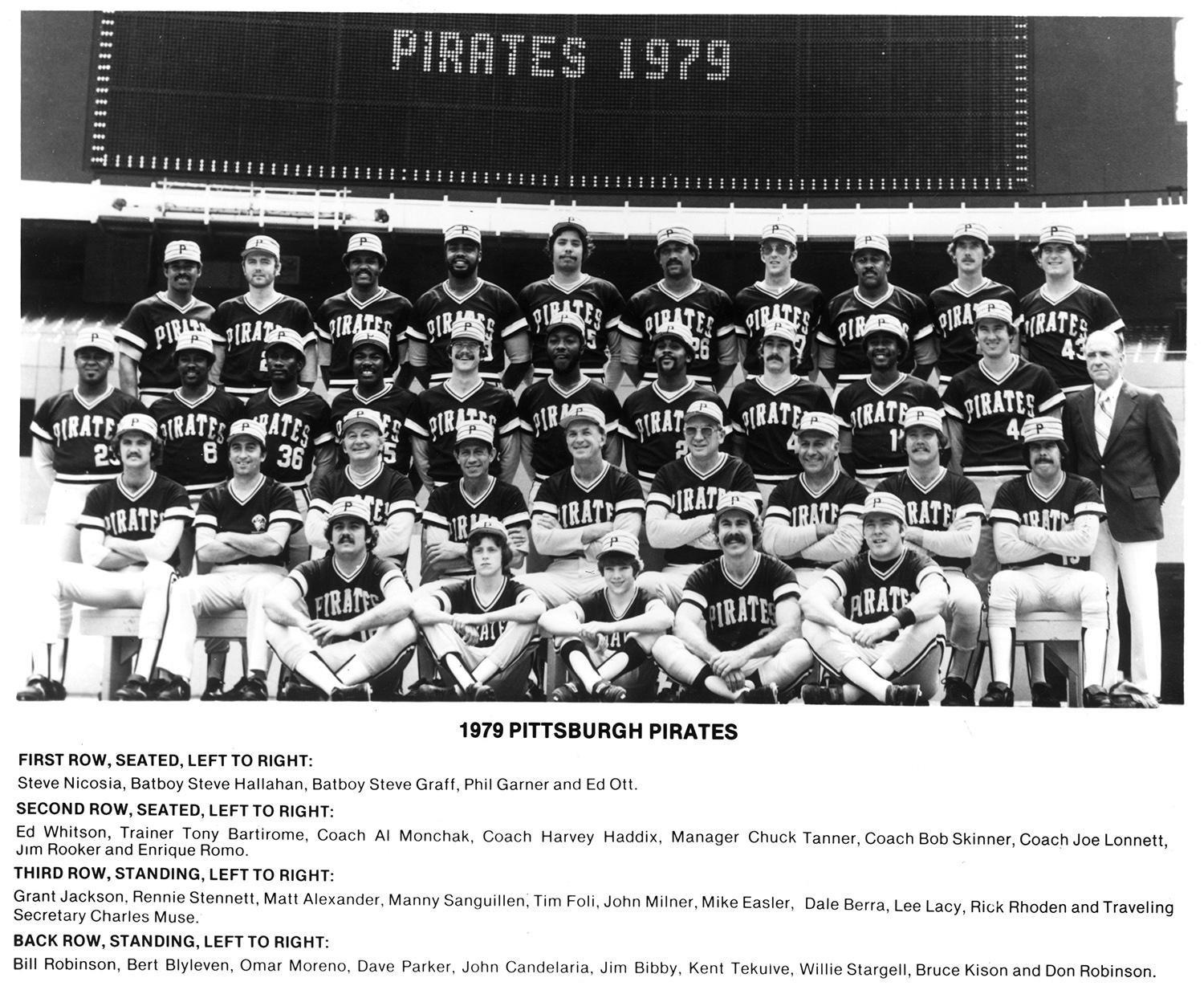

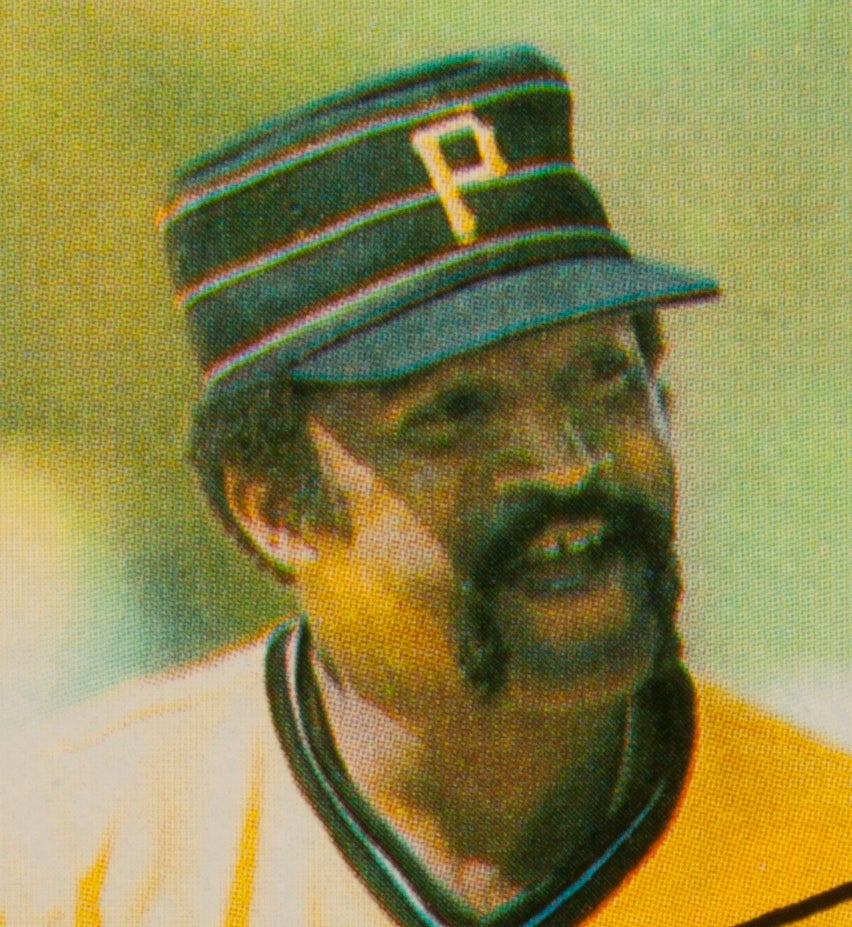

Foli lasted one season as the Mets’ shortstop before finding himself on the move again in the opening days of the 1979 season. That’s when the Mets made the career-changing decision to trade Foli to the Pittsburgh Pirates for a younger shortstop, Frank Taveras. The trade gave Foli the chance to play for a manager who suited him well, the upbeat and optimistic Chuck Tanner. Under the positive influence of Tanner, and surrounded by a group of free-spirited teammates, Foli began to relax. He played the best ball of his career in 1979, hitting .288, driving in a career-high 65 runs and serving the Pirates as an effective No. 2 hitter behind leadoff man Omar Moreno.

The additions of Foli and Bill Madlock, another trade acquisition, helped stabilize the Pirates’ infield. After a slow start to the season, the Pirates won the National League East. Foli played his part, and continued to do so in the postseason. Hitting .333 in both the Championship Series and the World Series, Foli helped the Pirates win the world championship over the favored Baltimore Orioles.

Foli would never match that level of production again, in part because of injuries. In 1980, an infection in his leg limited him to 127 games. In 1981, some minor injury concerns, along with the player strike of 1981, held him down to 86 games.

By now, the Pirates were an aging team in decline. After the 1981 season, the Pirates traded Foli, sending him to the California Angels for young catcher/outfielder Brian Harper. The trade afforded Foli a reunion with Mauch, his former manager in Montreal. Foli played well for Mauch, fielding his position almost flawlessly and leading the American League in sacrifice bunts. The Angels won the American League West before losing to the Milwaukee Brewers in the Championship Series.

The 1982 season turned out to be last productive year of Foli’s career. In 1983, his season came to an end in August because of an injury to his rotator cuff. He also created a bit of controversy in September, during a game that was being delayed by rain. Breaking team rules, Foli took off his uniform and donned his street clothes during the delay. The Angels hit him with a brief suspension and a fine for the transgression.

For the most part, Foli had learned to calm his temper by the time he played for the Angels in the early 1980s. He credited his renewed faith in Christianity, something that had happened during his days in Pittsburgh. “Everything used to get to me, but then I changed my priorities,” he told the Arizona Republic. “Jesus Christ became the lord of my life. Baseball is still important to me, but it’s not the only thing I have now.”

Now 33 years old, Foli had adopted a better mindset to play the game, but also had trouble staying healthy. Given that shortcoming, Foli became trade bait after the 1983 season. At the Winter Meetings, the Angels found a taker; they sent him to the New York Yankees for minor league reliever Curt Kaufman. The move seemed like a strange one for the Yankees, given the crowd that they had already assembled at shortstop: veteran Roy Smalley and prospects Bobby Meacham and Andre Robertson. Unlike Smalley, Foli had little power. He also lacked the range of either Meacham or Robertson.

Foli started the 1984 season as the Yankees’ regular shortstop, but soon found himself in a platoon with Meacham, before being demoted to a utility role. By the end of the season, Foli appeared in only 61 games, and achieved a statistical oddity, hitting .252 for the third consecutive year. One of the few consolations from his season in the Bronx was his relationship with Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. He took a liking to “The Boss,” praising him for his intense desire to win.

Steinbrenner liked Foli, too, but the mutual admiration could not keep him in pinstripes. After the season, the Yankees packaged Foli with Steve Kemp, sending them both to the Pirates in a deal for a young Jay Buhner, Dale Berra and Alfonso Pulido. Foli would play part of one season for his old team before being released. He attempted a brief comeback in the minor leagues, but decided to call it quits after only one game.

Foli made a quick transition from playing to coaching, putting in time on the staffs in Texas and Milwaukee. Although Foli had clearly mellowed, his fiery side still blazed from time to time. As a coach, he continued his habit of bench-jockeying opposing players. On one occasion, he so infuriated an opposing player – Don Baylor – that the slugger had to be restrained from physically retaliating against Foli. Foli also brawled with Oakland third base coach Tommie Reynolds during a bench-clearing fight that became particularly nasty.

In the year 2001, Foli became the bench coach of the Cincinnati Reds. His tenure would turn out to be somewhat tumultuous, most notably for a physical confrontation with fellow Reds coach Ron Oester. Much like his scrap with Ed Kranepool years earlier, Foli came out on the short end. He lost the fight and required a series of stitches afterward.

I’m happy to say that Foli is a much calmer man these days. I had the chance to meet him during the summer of 2009, when he was working as the manager of the Syracuse Chiefs, the Triple-A affiliate of the Washington Nationals. The Chiefs happened to be playing an exhibition game at Cooperstown’s historic Doubleday Field. Prior to the game, I asked Foli if he might be available for an interview. He graciously agreed. We talked for 10 minutes, with Foli supplying calm, level-headed, and thoughtful answers about his days in baseball and his managerial beliefs.

There was no sign of anger, no hint of temper. Instead, Foli came across as a solid, even-keeled voice of reason. I thought to myself, “This is a good guy.”

It seems the days of Crazy Horse are no more.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty