- Home

- Our Stories

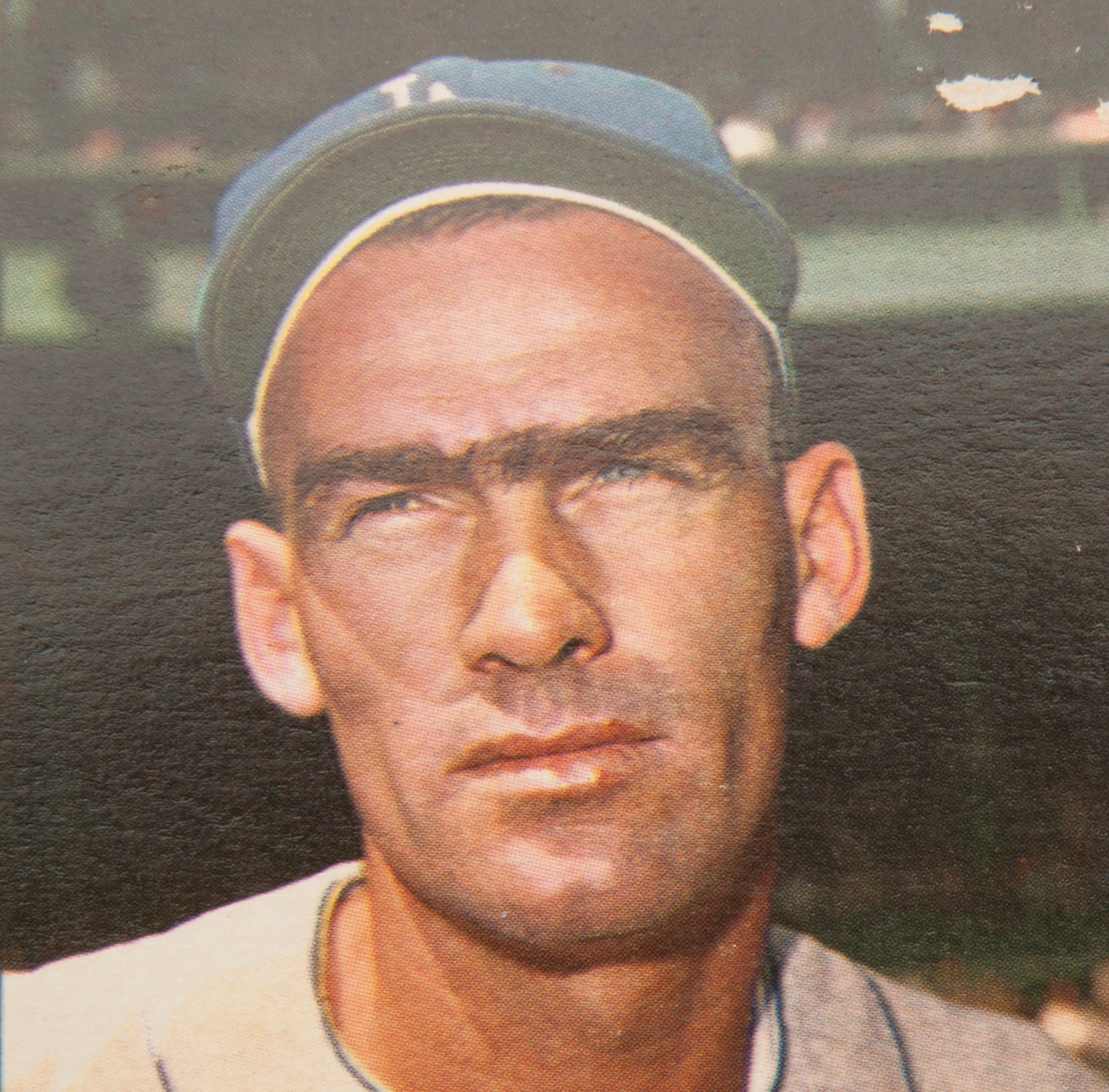

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Herman Franks

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Herman Franks

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

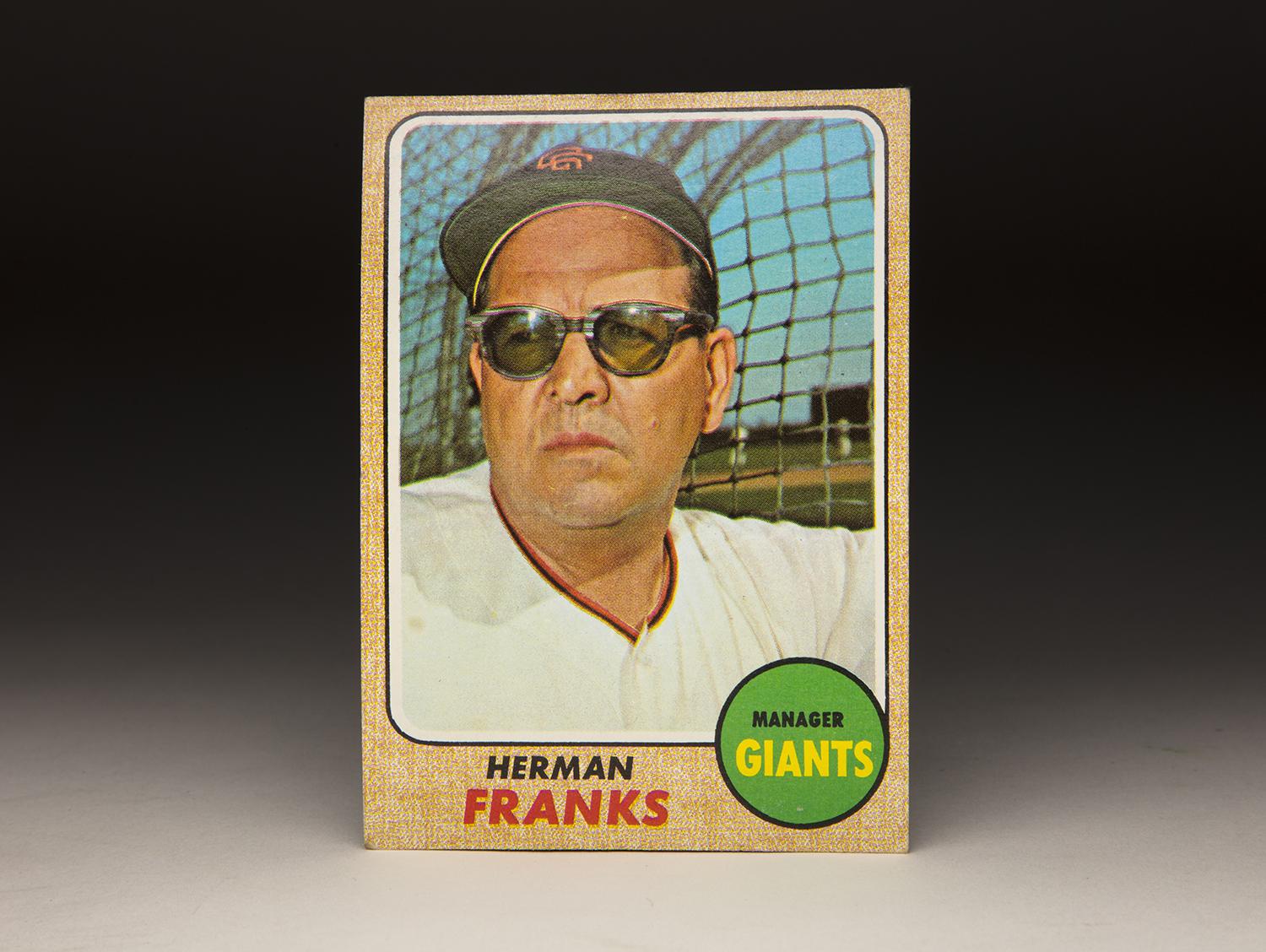

It’s not often that you’ll find cards that show ballplayers wearing sunglasses. It’s even more difficult to find cards of managers wearing shades. Thankfully, Herman Franks provides us with one of those exceptions, courtesy of his 1968 Topps card.

With those dark glasses, along with something of a scowl, Franks looks pretty darn intimidating in this Spring Training photograph. Clearly, Franks was a serious man, one who meant business. He could get mad at his players for making mistakes, and let them know in no uncertain way about it. But don’t let the photo fool you; he could forgive his players very quickly, too. For the most part, his San Francisco Giants liked to play for him.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The Franks card is one of the more intriguing selections to be found in the 1968 set. I’ve become a big fan of ’68 Topps, mostly because I like the distinctive speckled border that the company introduced that spring and summer. The speckled border is unusual but attractive; for some reason, the nature of the border gives the cards some three-dimensionality. I also like the colored circle that Topps showcases in the lower right-hand corner of the card. Thanks to the splash of color, the speckled borders, and the generally solid photography, 1968 Topps remains an appealing set that is attractive to collectors.

The Hall of Fame’s collection features the complete set of 1968 Topps, which always gives me a good reason to venture into the basement and check out the binders containing these wonderful cards. In turn, the discovery of these cards give me a good excuse to do some research and learn more about the players – and the managers – from this time period.

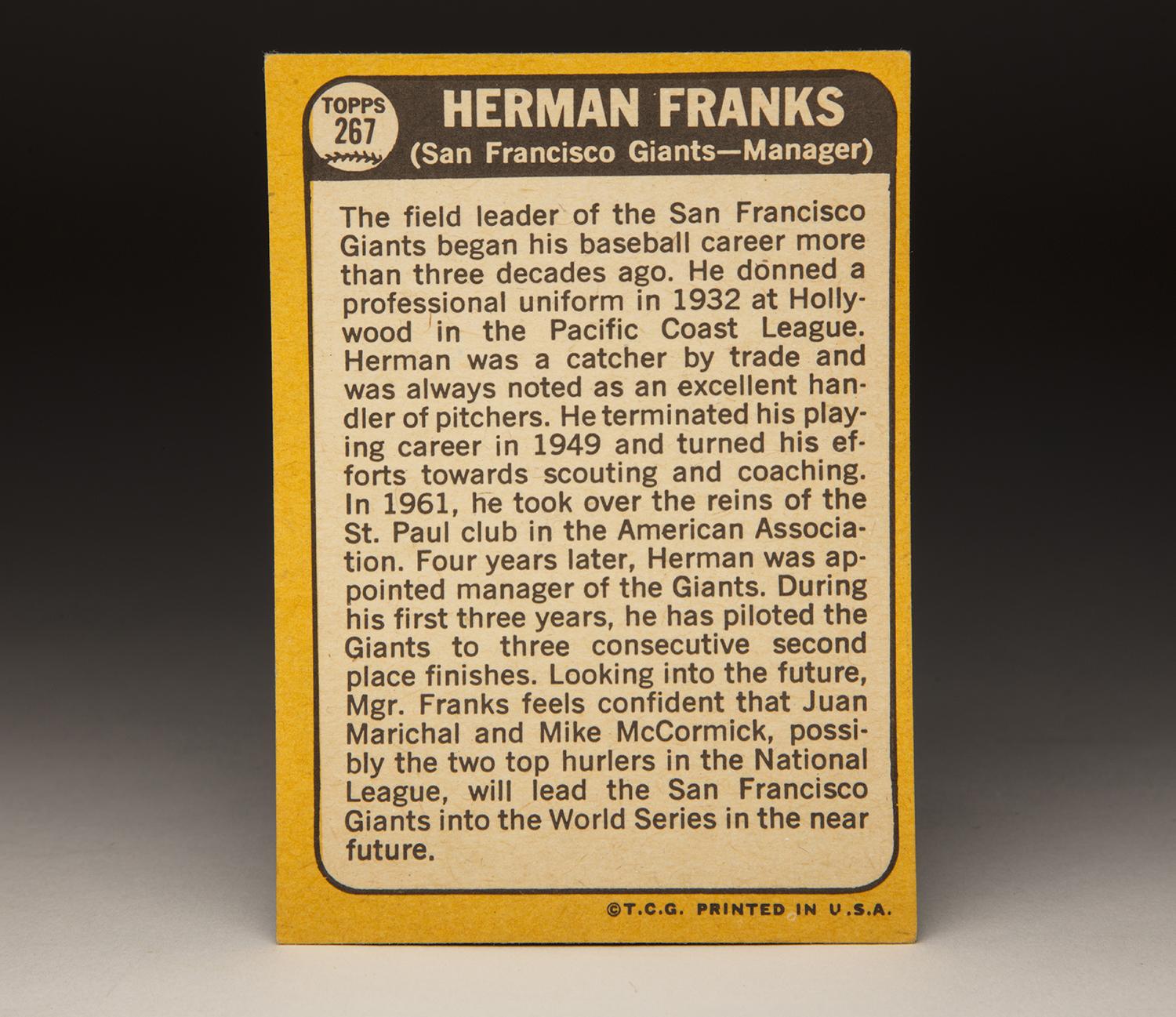

The back of the Franks card gives us a nice bonus, too. Rather than simply show us Franks’ managerial won-loss record (which can be a pretty dry summary of a manager’s career), the reverse contains a well-written biography of the player-turned manager. (The back’s color scheme of white and yellow makes the bio easy to read, too.) If you knew nothing about Franks prior to picking up this card, you would come away with a good snapshot of a man who was clearly a dedicated baseball lifer.

As a ballplayer, Franks put in time as a backup catcher with the St. Louis Cardinals and Brooklyn Dodgers. His career appeared to end in 1941, not so coincidentally with the start of World War II. But five years later, after his discharge from the Army, he made a comeback with the Montreal Royals, where his teammates included a young Jackie Robinson. Franks played the entire season as the Royals catcher and put up an excellent year, hitting .280 with 14 home runs.

After a stint as player/manager with the St. Paul Saints, Franks returned to the major leagues with the Philadelphia A’s, beginning the second phase of his career. That phase lasted parts of three seasons with the A’s and New York Giants, before finally ending in 1949. With the Giants, Franks became a player/coach; he was personally recruited by manager Leo Durocher, who wanted Franks to work with the Giants’ young pitchers. For the better part of the next decade, Franks coached and scouted for the Giants, maintaining a strong relationship as one of Durocher’s lieutenants.

The most famous incident of Franks’ coaching career occurred during the 1951 season, when the Giants rallied from 13-and-a-half games back to force a three-game playoff against the Brooklyn Dodgers. Franks spent at least part of the final game of that playoff – the famed Bobby Thomson game – in the Giants’ clubhouse, which was located in center field. Publicly, Franks never admitted to what he was doing in the clubhouse, but several of his teammates claimed that he had been positioned there by Durocher. Armed with a telescope, Franks allegedly stole the signs of the Dodgers’ pitchers and then relayed them to Giants catcher Sal Yvars through a buzzer system.

Remaining with Durocher for the rest of his Giants tenure, Franks retained his coaching position under new manager Bill Rigney. Franks stayed on as a coach for one season, but ultimately Rigney wanted his own coaches. That was no problem for Franks, who was already starting to experience success in private business, largely through his real estate holdings. Some writers speculated that Franks was worth at least $1 million, which was simply unheard of for an ex-ballplayer in the 1950s.

By the 1960s, he was doing well enough to make a bid to own the New York Yankees. Backed by the Lehman Brothers, Franks’ bid for the Yankees fell short to the competing bid from CBS.

Prior to his interest in the Yankees, Franks did become the owner and general manager of a minor league team, the Salt Lake Bees. In 1961, Franks took on the added burden of being the team’s manager, as well, but after eight games, he decided that the workload was too great. He resigned the post, so as to concentrate fulltime on his primary role of running the team as the GM.

Franks returned to the major leagues in 1964, once again resurfacing as a coach with the Giants, this time under Alvin Dark. Within hours of the season’s end, the Giants fired Dark and announced the hiring of Franks. For Franks, the opportunity to manage represented the chance of a lifetime, especially given the talent on the Giants’ roster.

“This club definitely has possibilities to win the pennant. If I didn’t think they could win it, I wouldn’t have taken the job,” Franks said at the press conference announcing his hiring.

As a manager, Franks modeled himself after Durocher and believed in old school baseball. He wanted his pitchers to brush back hitters and his baserunners to take out middle infielders. But he also railed against the concept of micro-managing, believing that it was important “to let the players play.” Under Franks’ direction, the Giants posted four consecutive winning seasons, with win totals ranging from 88 to 95 games.

Among others, longtime San Francisco writer Bob Stevens became an admirer of the heart and passion that Franks showed in executing his job. “When you’ve seen him, in a burst of unrestrained joy, explode from the dugout to congratulate a winning pitcher,” Stevens wrote for the Sporting News, “then you know how much of himself he throws into the game.”

As well as the Giants played for Franks, they always fell short of the postseason. In the highly competitive National League, where talented teams like Los Angeles and St. Louis reigned, the Giants could finish no higher than second place. Prior to the 1968 season, Franks met with Giants owner Horace Stoneham, telling him that if the team did not win the pennant, he would quit at season’s end. The Giants finished second to the Cardinals, and sure enough, Franks resigned his position, despite having the best managerial record in the game over the last four seasons. According to Giants coach Joey Amalfitano, Franks regretted ever telling the owner that he would quit the job. He still enjoyed managing, but felt that it was important to live up to his word, so he carried through with his promise to resign.

Leaving managing and coaching aside, Franks continued to pursue his business interests. He also became the financial advisor to Willie Mays, one of his star players with the Giants. Franks’ strong business sense made him a natural for the position.

In 1970, Franks happened to be in Chicago meeting with Mays, who was in town for a series with the Cubs. Chicago pitching coach Joe Becker suffered a heart attack, leading him to be hospitalized, and eventually forcing him to retire from coaching. By now the manager of the Cubs, Leo Durocher contacted Franks about the possibility of stepping in as the team’s interim pitching coach. After meeting with his good friend, Franks decided to take the job, serving in that role through the end of the season.

Once again leaving the game, Franks remained on the sidelines for the next six seasons – until someone else came calling. After the 1976 season, the Cubs’ director of baseball operations, Bob Kennedy, fired manager Jim Marshall. Having known Franks from his days as a manager in Salt Lake, Kennedy contacted Franks about the Cubs’ managerial vacancy. The two men sat down and considered the possibility, with Franks deciding to take the job.

The Chicago media met the announcement with skepticism. They took note of Franks’ age; he was 63, making him the oldest manager in the game. They also wondered whether Franks, who was independently wealthy from his business dealings, really wanted to manage. Some of the writers also criticized Franks for his handling of the media while with the Giants. Franks had a reputation for snapping at writers, especially those who questioned his decisions.

Franks didn’t care about the various criticisms. He said he had two goals, to win a lot of games, and to win a pennant before he retired. Taking over a sub-.500 Cubs team that had won only 75 games in 1976, Franks did well, leading the club to a six-game improvement. The Cubs played respectably, going 81-81 and proving that Franks could still manage major leaguers. With his pot-bellied figure and his tendency to engage in epic arguments with umpires, the cigar-chomping Franks became a colorful figure in the Windy City.

In the spring of 1978, Franks showed himself to be more than capable of having fun on the job. After a Spring Training workout, the Cubs made their way into the clubhouse, where Franks took the hairpiece from Cubs third baseman Steve Ontiveros and placed it on top of his own head. (Franks himself was bald, too.) A Chicago Tribune photographer captured the surreal moment on film.

That summer, the Cubs fell back slightly, winning 79 games for Franks. Then came the fateful 1979 season, as the Cubs again played close to .500 ball. In late September, with the team one game over .500, Franks had an interesting conversation with a local reporter. Claiming to be fed up with the job, Franks criticized some of his players, calling them “crazy.” He also showed a local reporter a $24,000 check that he had written out to a Salt Lake City country club. Franks said the check was proof that he was planning to quit the team; he planned to spend most of 1980 playing golf at the club.

The reporter went public with the story, which Franks denied. A few hours later, Franks reversed course and announced his resignation. The news was greeted with more criticism from the Chicago media, which claimed that Franks had lost touch with the modern day player. For his part, Franks claimed that the age difference between him and his players mattered little. Defenders of Franks, including venerable writer Jerome Holtzman, pointed to his record, which was above .500 despite the Cubs’ many shortcomings as a team. For his career, Franks won 53 percent of his games as a manager.

After his resignation, Franks let loose with criticism of certain players on the Cubs. He specifically targeted Barry Foote, Bill Buckner, Ted Sizemore and Mike Vail. In an interview with Dave Nightingale, Franks claimed that Buckner “doesn’t care about the team” and that Vail “was a constant whiner.”

Some observers assumed that Franks, having burned his bridges, was done with baseball. Yet again, he would prove them wrong. After the Cubs endured a horrible start to the 1981 season, general manager Bob Kennedy resigned. Cubs owner William Wrigley turned to Franks, asking him to take over the job on an interim basis. Franks agreed, but only if he was given “complete control” over the operations of the team. Wrigley relented to the demand.

Franks remained on the job for the rest of the season. He expressed interest in taking over the job fulltime, but Wrigley chose a different direction, instead hiring Dallas Green. As a consolation, Wrigley offered Franks two different jobs, one as a broadcaster and the other as the head of the team’s marketing department. Franks turned down both of the offers.

Willing to leave baseball behind, Franks again turned to his private business. In addition to serving as Willie Mays’ financial advisor, he did the same for Willie McCovey and Ernie Banks, among others. He also made numerous public speaking appearances, where he spun stories from his days as a player and manager.

Enjoying retirement, Franks lived a long and happy life. He died quietly in 2009—at the age of 95. While never a household name, he managed to have an impact on the game that he loved, before leaving it on his terms. And he made life better for a few ballplayers smart enough to tap him for his business acumen.

For many ex-ballplayers and managers, life can be a struggle after baseball. But for Herman Franks, that was not the case. He found as much success outside of the game as he did inside the lines. He also brought some color to the game, with his cigars, his round belly, and a pair of dark sunglasses that would have made Dirty Harry proud.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

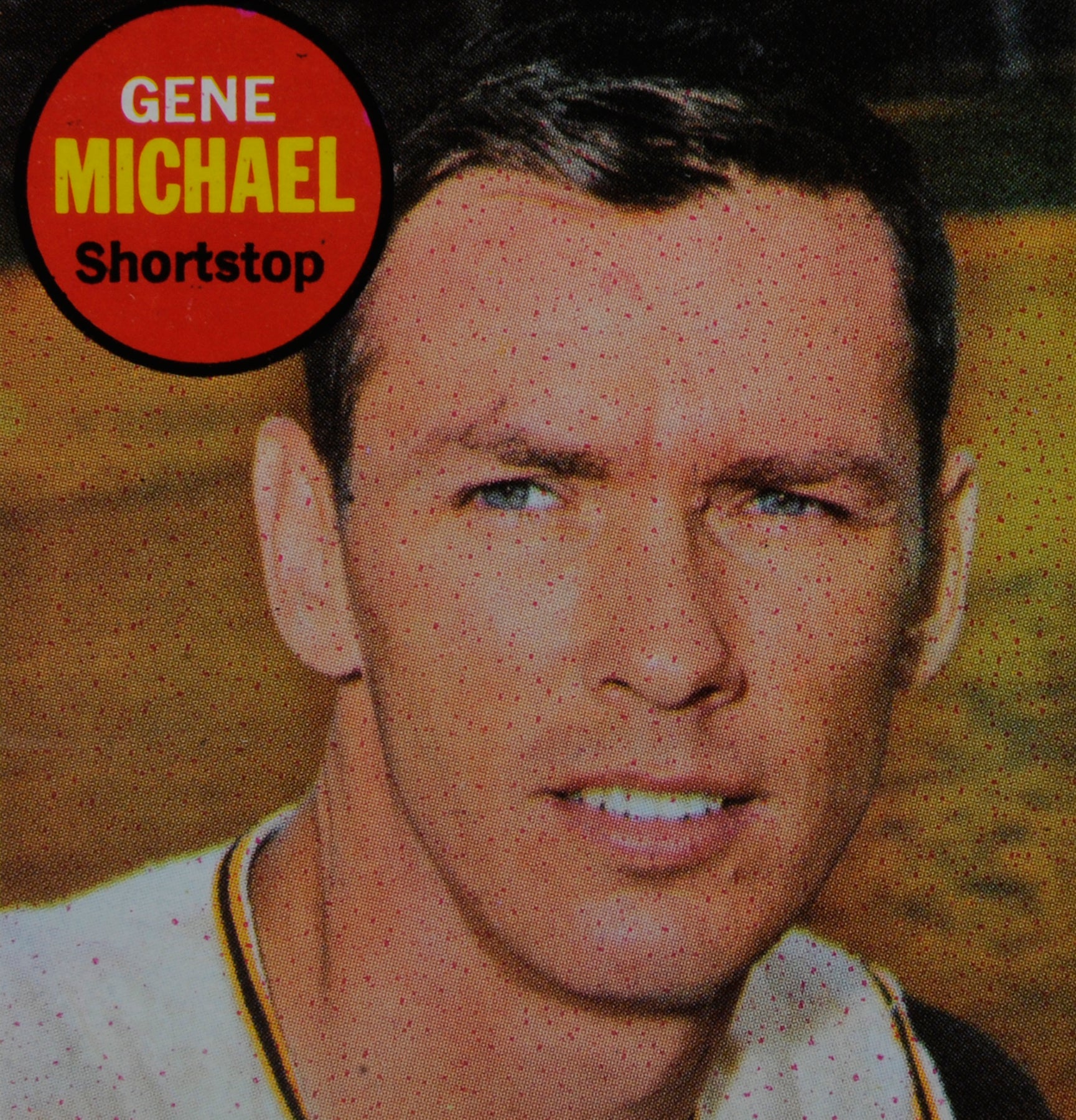

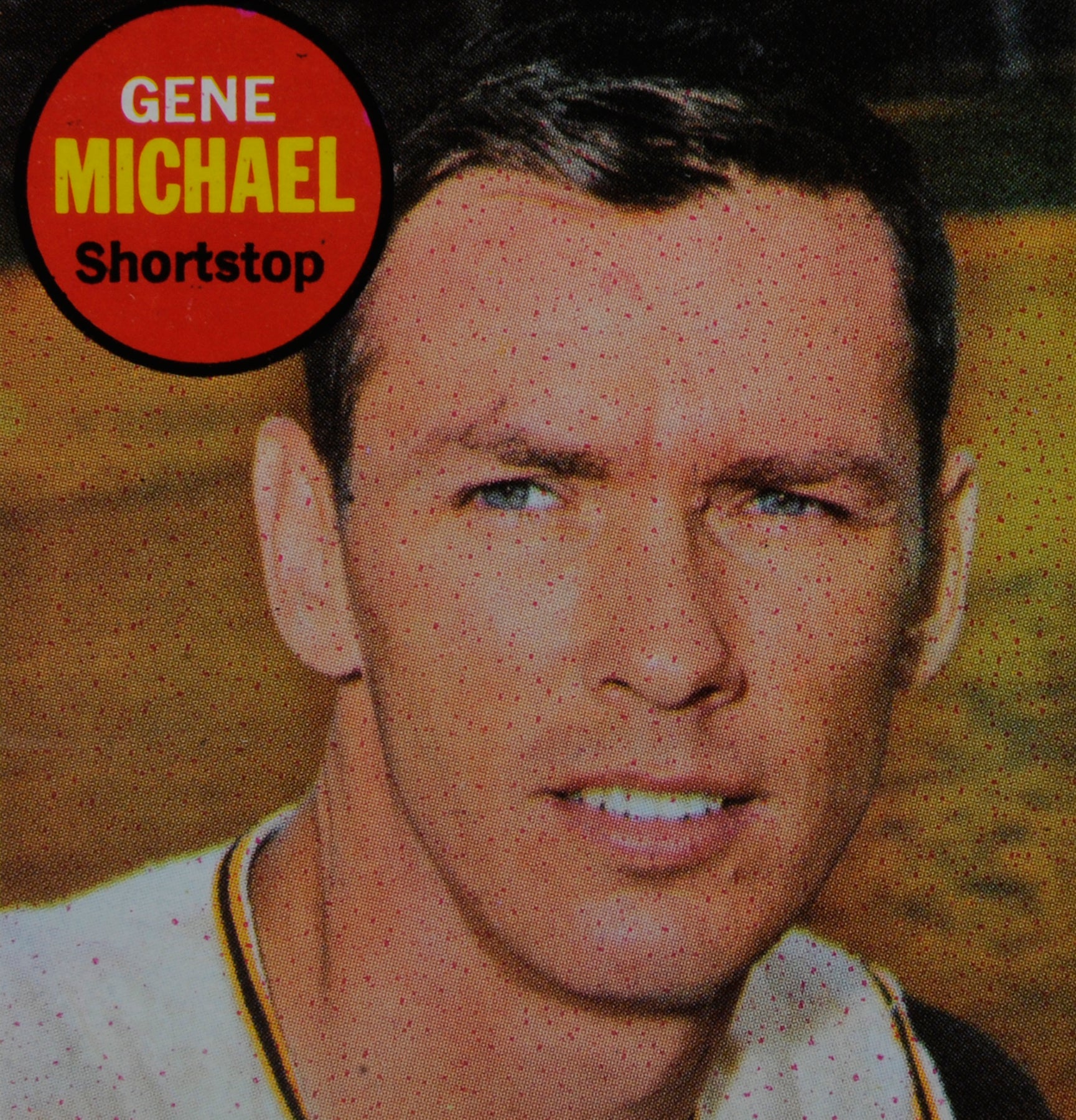

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

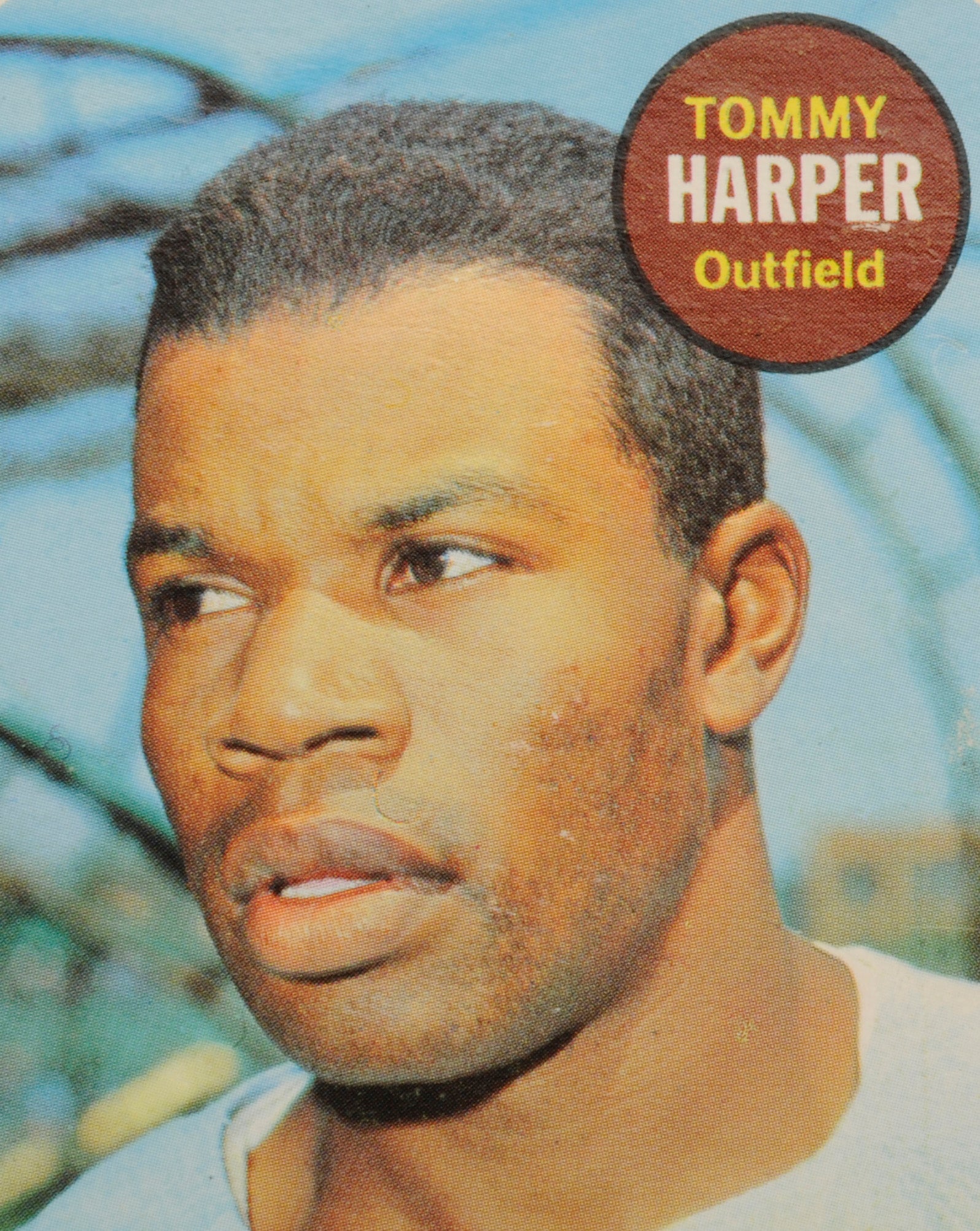

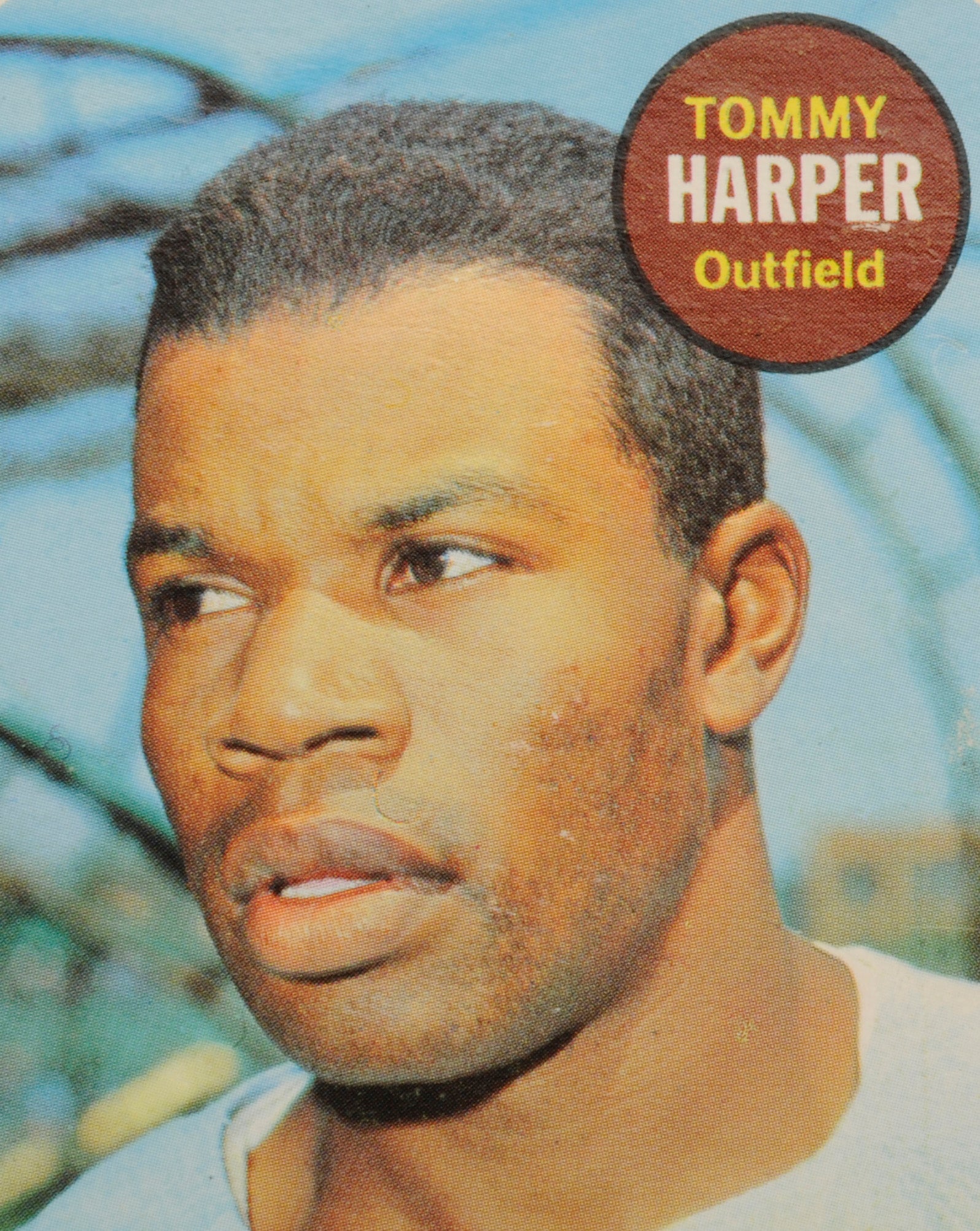

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Tommy Harper

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

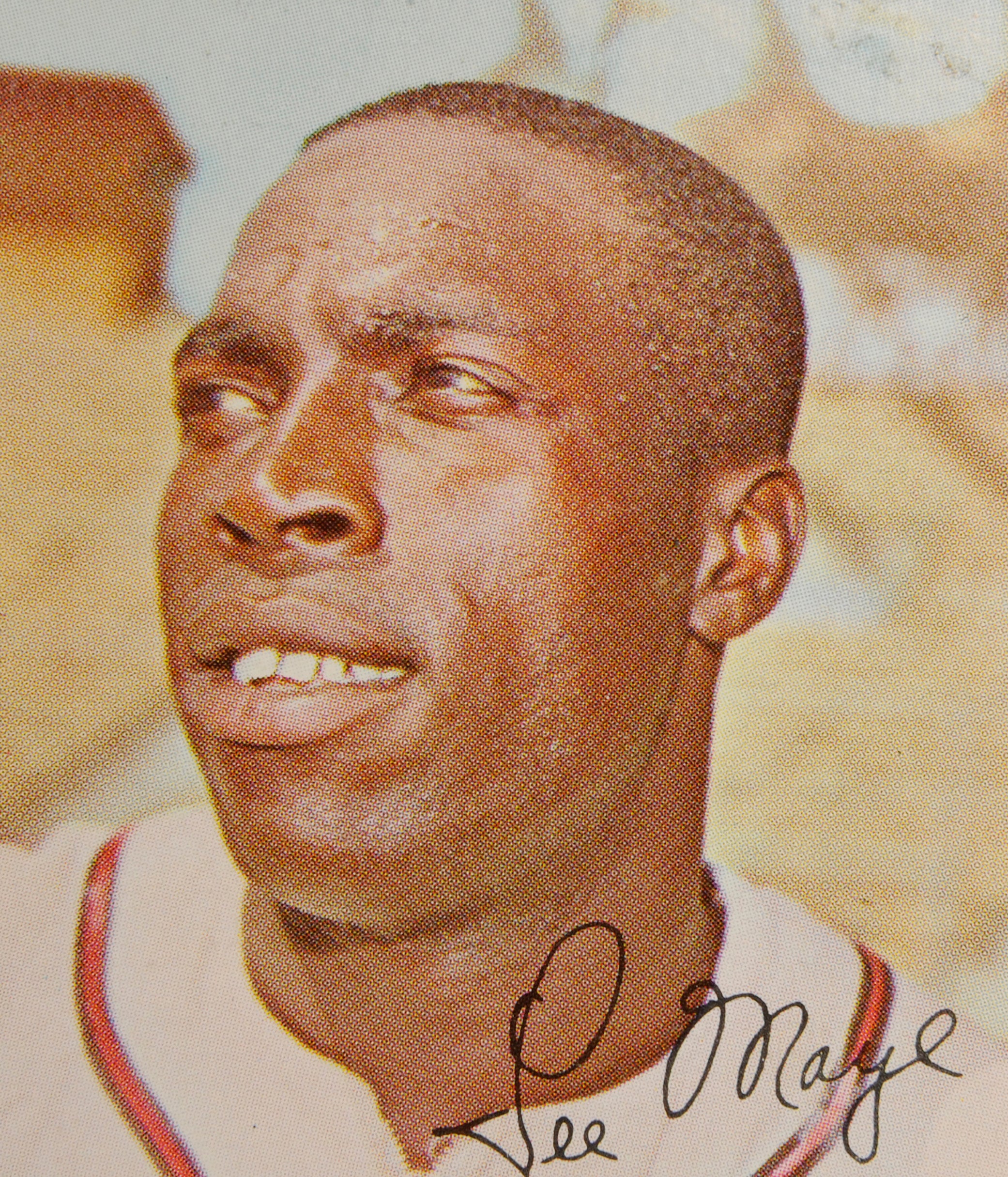

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Tommy Harper

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon