- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Bob Tillman

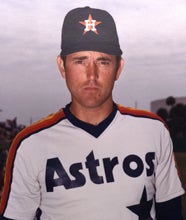

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Bob Tillman

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

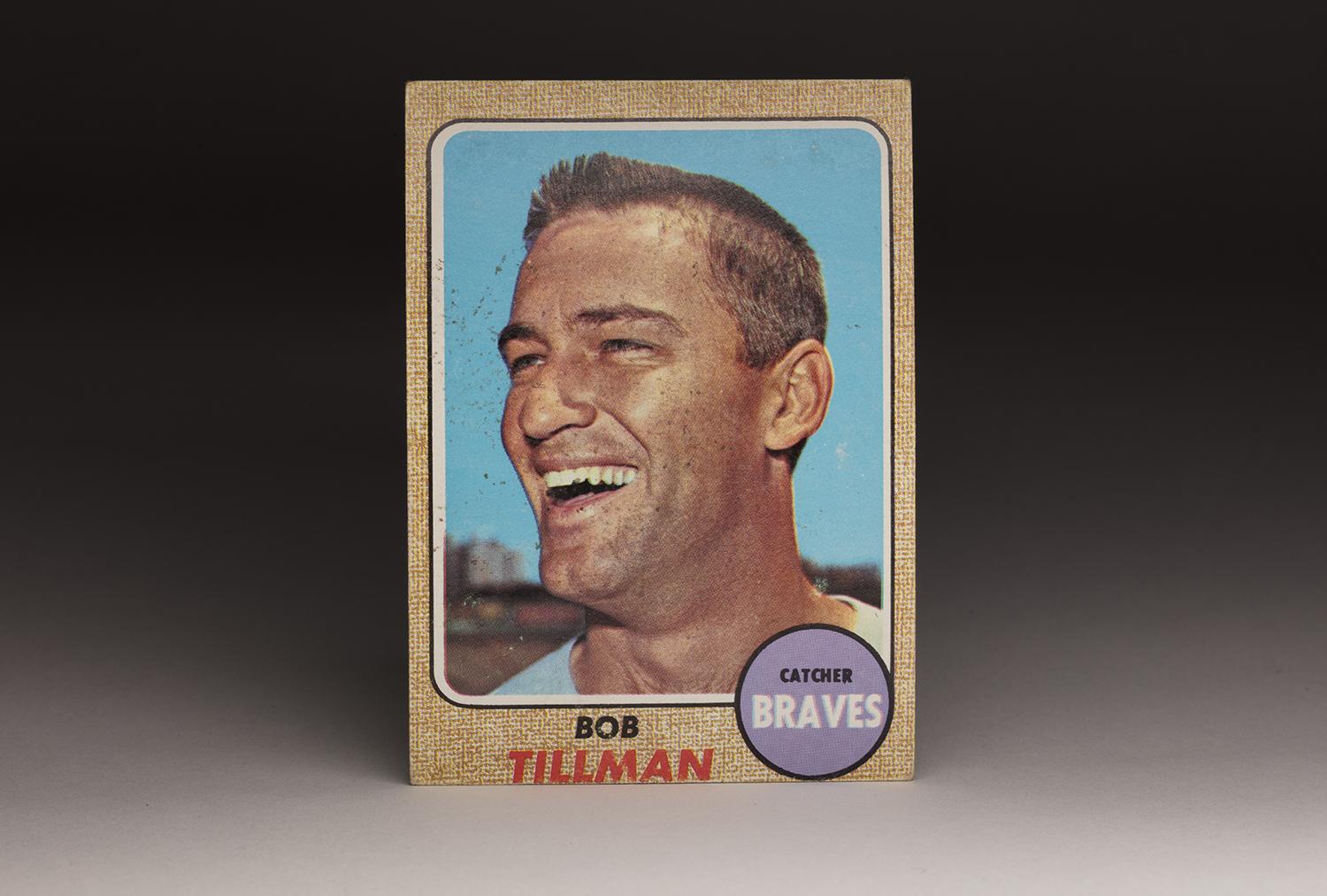

Every once in a while, you’ll stumble onto a baseball card that shows a player smiling widely. Not one of those posed “I’m just doing it for the camera” smiles. But something enthusiastic and genuine.

For example, on his 1969 card, Ernie Banks is smiling like he’s just won the lottery. We see a similar expression from Ron Klimkowski on his 1972 Topps card. Jim Kern’s 1979 Topps card, in which he looks to be laughing, gives us another example. Then there is Doug Rader’s 1989 Topps Traded card, which captures him in full chuckle.

Frankly, that’s the way it should be. Being a major league ballplayer, particularly during the relaxing days of Spring Training, and having your picture taken so that it can be placed on a card, should be a joyous occasion. How many of us would love the chance to be on an authentic baseball card, even once?

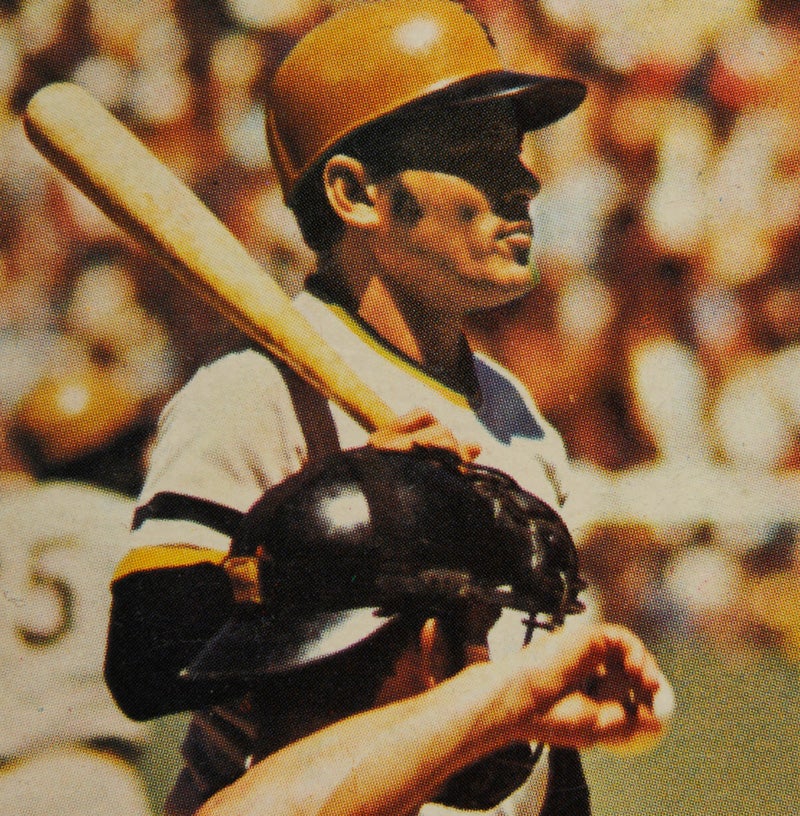

I’m not sure that anyone can top Bob Tillman’s facial expression on his 1968 Topps card. He’s not just smiling, but laughing and doing so quite demonstrably. It’s as if someone, perhaps the photographer from Topps, just told him the most amusing joke he had heard in weeks. Or perhaps Tillman was simply in a good mood that day, fully appreciative of his status as a member of a major league team. At the time, there were only 20 big league clubs, with approximately 500 available jobs for the players known as “the best of the best.” For a player like Bob Tillman, the awareness of being a major leaguer might have brought the following realization: “I’m a big league ballplayer, and somehow I’m being paid to do this.”

Of course, I’m reading a lot into this Tillman card. I wasn’t there on that Spring Training day, likely in February or March of 1967, when Topps snapped this picture of Tillman. But I’d like to think he was a good guy who was happy about his fate in life. Just seeing the joy of Tillman on this old card made me want to learn more about a journeyman player who has long since been forgotten by most fans. And as I came to learn, Tillman was regarded as one of the game’s nice guys, a man who was always popular with teammates.

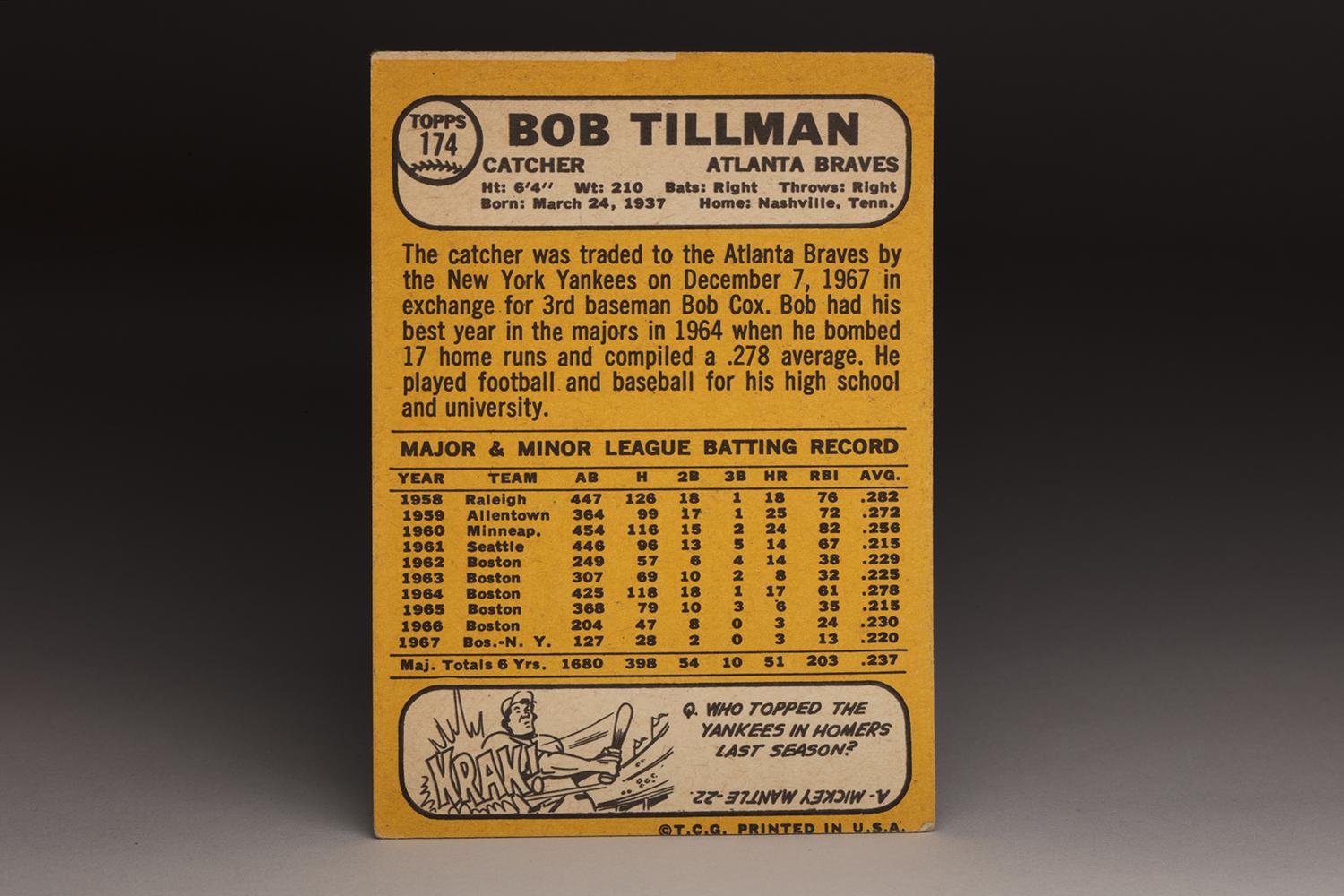

Bob Tillman, pictured above, was still on the Boston Red Sox when his Topps card was taken. So Topps featured an image of Tillman without a hat, and for his 1968 card designated him as a member of the Atlanta Braves, a team he had been traded to in December of 1967. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame)

It’s also worth noting that Tillman’s card designated him as a member of the Atlanta Braves, but he appears hatless on his 1968 card. This was a trick that Topps used frequently with ballplayers who moved from team to team. Assuming that the photograph was taken during the spring of 1967, Tillman was still with his original team, the Boston Red Sox. In August, the Red Sox sold him to the New York Yankees, where he finished out the season. Come December, the Yankees traded Tillman to the Atlanta Braves in a deal for future Hall of Famer Bobby Cox.

For a middle-of-the-road player like Tillman, the frequent travels that sent him from Boston to New York to Atlanta should have come as no surprise. For most players, making the major leagues is a struggle to begin with, and staying with one team can become an achievement of titanic proportions.

Tillman’s well-traveled journey began in 1958, when the Red Sox signed the right-handed hitting catcher out of Middle Tennessee State and assigned him to Raleigh of the Class B Carolina League. Within two years, Raleigh would become well-known in American culture through The Andy Griffith Show. Raleigh was the city that Andy and his friends often mentioned while living out their lives in tiny Mayberry. For Tillman, Raleigh became a real-life place where he first showed his talents on the professional stage. Tillman played well enough to earn a place on the Carolina League All-Star team and pick up a promotion to the Eastern League the following spring.

By 1962, the Red Sox had seen enough of Tillman to bring him to the major leagues. They raved about his defensive skills, with some in the organization calling him the best defensive catcher in the minor leagues. The Sox used him as a third-string catcher – in an era when teams typically carried three receivers – employing him as a backup to Jim Pagliaroni and Russ Nixon.

Tillman improved his status quickly, graduating from third-string catcher to part-time starter. By the end of his rookie season, he appeared in 81 games, hitting 14 home runs and slugging a respectable .454. In fact, Tillman played so well as a rookie that the Red Sox felt comfortable trading Pagliaroni during the winter. The Sox sent “Pag” to the Pittsburgh Pirates for slugging first baseman Dick Stuart and pitcher Jack “Tomato Face” Lamabe.

Even with his rookie success, Tillman remained his harshest critic. He lamented his .229 batting average. In a later interview, he admitted that he “couldn’t hit a curveball with an oar.” In light of his problems with the curve, the Red Sox sent him to the fall Instructional League for additional work.

The Red Sox clearly liked Tillman, with their only criticism having to do with his status as one of the game’s nice guys. “He’s too polite,” Red Sox batting coach Rudy York told the Sporting News. Just watch him. He apologizes in the clubhouse… You can carry this gentleman stuff too far.”

Whatever the reasons, Tillman continued to struggle against breaking pitches in 1963. Not only did his batting average fall further to .225, but his power disappeared, as he hit only eight home runs. Defensively, Tillman became a liability against the running game, throwing out only 16 percent of opposing baserunners. Due to his lack of hitting and throwing, Tillman ended up splitting time with Nixon and failed to place a stranglehold on the position.

In 1964, Tillman reported to Spring Training in better physical condition and proceeded to regain the No. 1 catching job. He also assembled the best season of his career, batting .278 and clubbing 17 home runs. The Sporting News referred to him as “Tillie The Terror.” As a right-handed hitter with power, Tillman seemed like a perfect fit for Fenway Park. He also showed improvement in his throwing, which had become a problem the previous summer.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Unfortunately, Tillman couldn’t sustain his offensive improvement. A slow start to the 1965 season buried his batting average under .200, where it remained in late June. Fans at Fenway Park booed him. He lost playing time to Nixon and newcomer Mike Ryan, a stronger defensive catcher. By 1966, Tillman was reduced to a backup role, behind Ryan. When Tillman started the 1967 season slowly, Tillman found himself in the doghouse of manager Dick Williams. In particular, Tillman’s throwing problems became a concern for Williams. Tillman often sat on the bench for weeks at a time, with seemingly his only purpose to serve as an extra bullpen catcher.

Later that summer, the Red Sox acquired Elston Howard in a trade, giving them a glut of four catchers. Someone had to go. That would be Tillman. Thus began the merry go round of transactions that sent Tillman to New York and then Atlanta in a matter of months.

By the spring of 1968, Tillman knew that he would fill the role of second-string catcher, behind All-Star Joe Torre, and ahead of Bob Uecker. Tillman played sparingly, hitting only .220, but became a favorite of manager Lum Harris, who praised the veteran catcher for his clutch hitting. “Luman’s made my job easy, really,” Tillman told Hal Hayes of the Atlanta Constitution. “I seldom go to the ballpark without knowing if I’m going to be playing or not. He always lets me know beforehand, so I’ll have a chance to prepare myself mentally.”

With Torre, one of the best hitting catchers in either league, entrenched behind the plate, Tillman likely figured that his backup duties would continue in 1969. That all changed during Spring Training. Torre held out of camp, unhappy with his contract situation. And then Tillman asked the Braves’ permission to leave camp for what he called “personal reasons.” Tillman never publicly specified what the personal reasons entailed, but his announcement immediately spurred rumors that he was about to retire.

In the meantime, the Braves fielded trade offers for Torre. At one point, they asked the Mets for a package of three players: catcher Jerry Grote, outfielder Amos Otis, and a young right-hander named Nolan Ryan. Understandably, the Mets said no.

On March 17, the Braves announced a blockbuster trade, sending Torre to the St. Louis Cardinals for All-Star first baseman Orlando Cepeda. The move left the Braves without their starting catcher and without their primary backup. All that was left were two rookies, Bob Didier and Walt Hriniak.

Even with the announcement of the trade, Tillman stayed out of camp. Finally, on March 24, after a layoff of two and a half weeks, he announced his return. Once again, he chose not to reveal specific reasons for his departure, but said the trip home proved beneficial. “That time off helped me. I know it did,” Tillman told Wilt Browning of the Atlanta Journal.

Back in camp, Tillman began the battle with Didier and Hriniak for the No. 1 catching job. Despite a late start to Spring Training, he beat out the two rookie receivers. For the fourth time in his career, Tillman earned an Opening Day start behind the plate. But his status as No. 1 catcher did not last long. He struggled to hit for average, eventually giving way to Didier, a superior defensive catcher with a cannon-like throwing arm.

Still, the season did produce some highlights for Tillman. For the year, he hit 12 home runs, a decent total for a part-time catcher. And for one day, he played as if his body had been taken over by Mickey Mantle. On July 30, Tillman hit three home runs at Connie Mack Stadium, victimizing Philadelphia Phillies left-hander Grant Jackson each time. The home run barrage overshadowed teammate Hank Aaron’s historic home run, a blast that moved him past Mantle for third on the all-time list.

The 1969 season also proved notable in that it gave Tillman the chance to play in his first postseason. The Braves clinched the National League West in the first year of division play. Tillman did not come to bat in the Championship Series, but did appear defensively in a three-game sweep at the hands of the Miracle Mets.

In 1970, Tillman became part of a three-man catching platoon, along with Didier and lefty-swinging Hal King. He played respectably, hitting .238 with 11 home runs. But he was now 33 and didn’t fit into Atlanta’s future. That winter, the Braves dealt him to the newly transplanted Milwaukee Brewers (formerly the Seattle Pilots) for utilityman Hank Allen, the older brother of star first baseman Dick Allen.

Brewers manager Dave Bristol announced that Tillman would play a significant role for the team in 1971. It didn’t happen; in fact, Tillman would never make it Milwaukee. Only two weeks after the trade, the Brewers changed general managers, firing Marvin Milkes and bringing in Frank “Trader” Lane, a man with a reputation for cleaning house and putting his own stamp on teams. Lane wanted a complete break from the previous regime, so he rid himself of two recent Milkes acquisitions. Lane traded outfielder/catcher Carl Taylor and gave Tillman his outright release.

Given his decent production in 1970 and the lack of catching depth around the major leagues, it seemed logical that some team would claim Tillman. No one did. He decided to pack his bags and call it a career after nine seasons.

Tillman returned to his home in Tennessee, where he worked for a luggage company and then a food distributor. He retired in 1998. In looking through his player file in the Hall of Fame’s Library, I was saddened to see that he died in 2000, having suffered a fatal heart attack. He was only 63.

Bob Tillman was one of those good guys whom you would have liked to see live into his nineties – if not longer. If there’s any consolation, it’s that we still have his 1968 Topps card, which reminds us of just how much he seemed to love his job playing in the major leagues.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

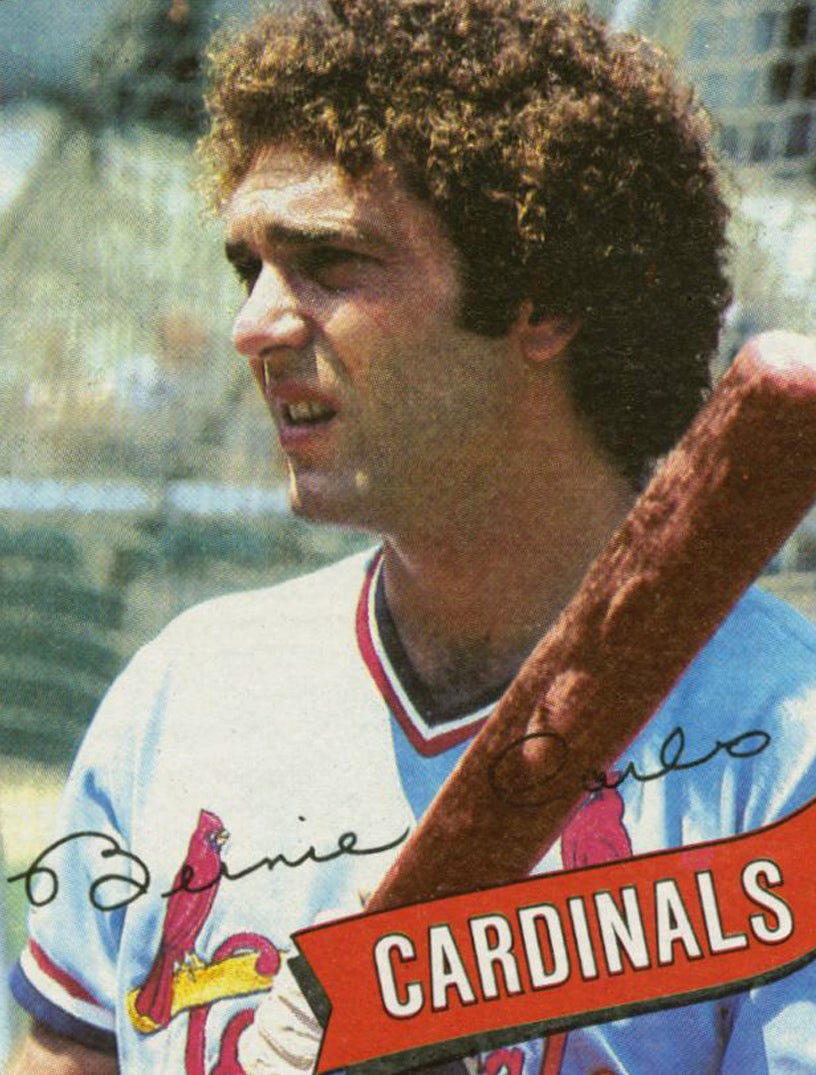

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

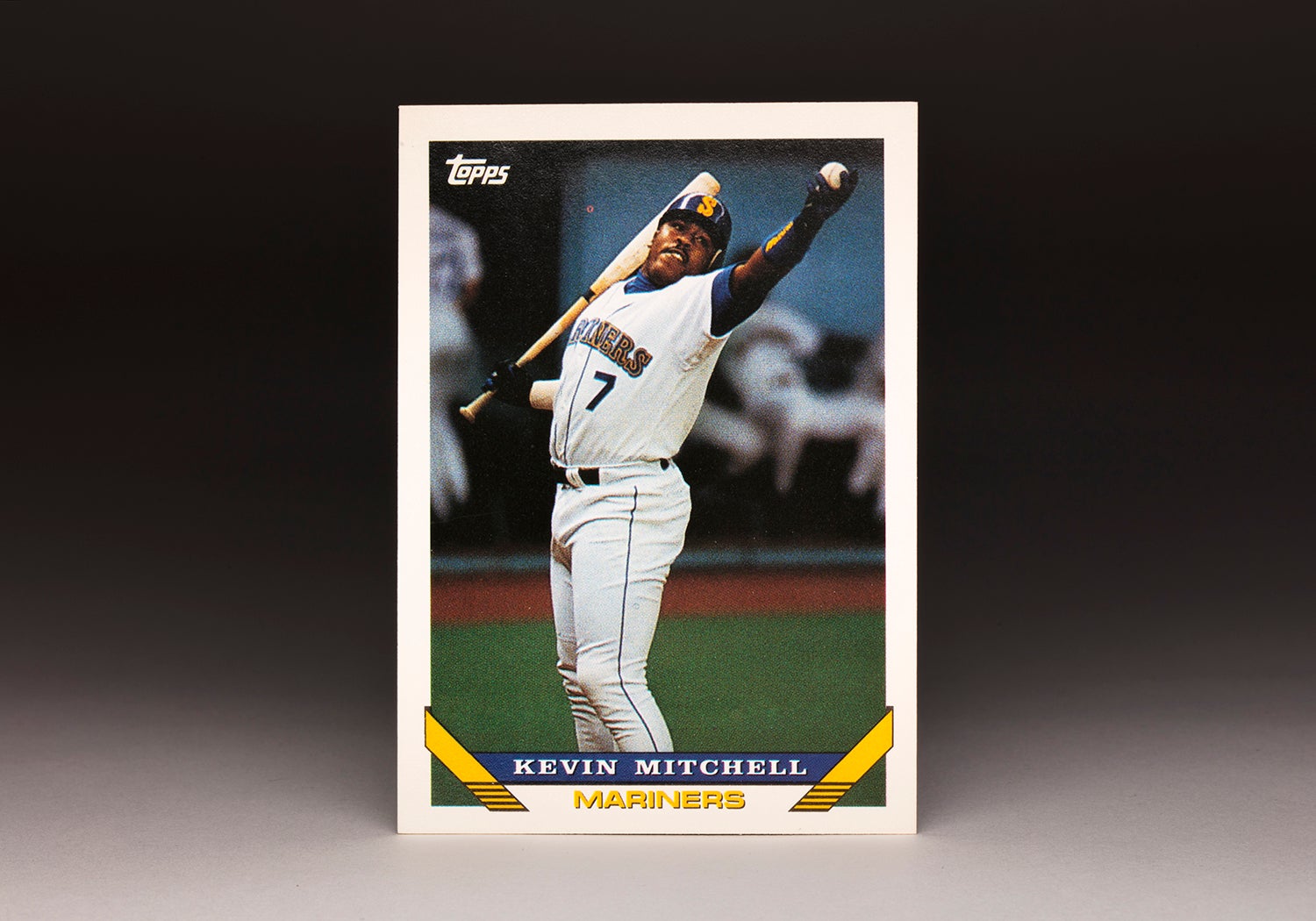

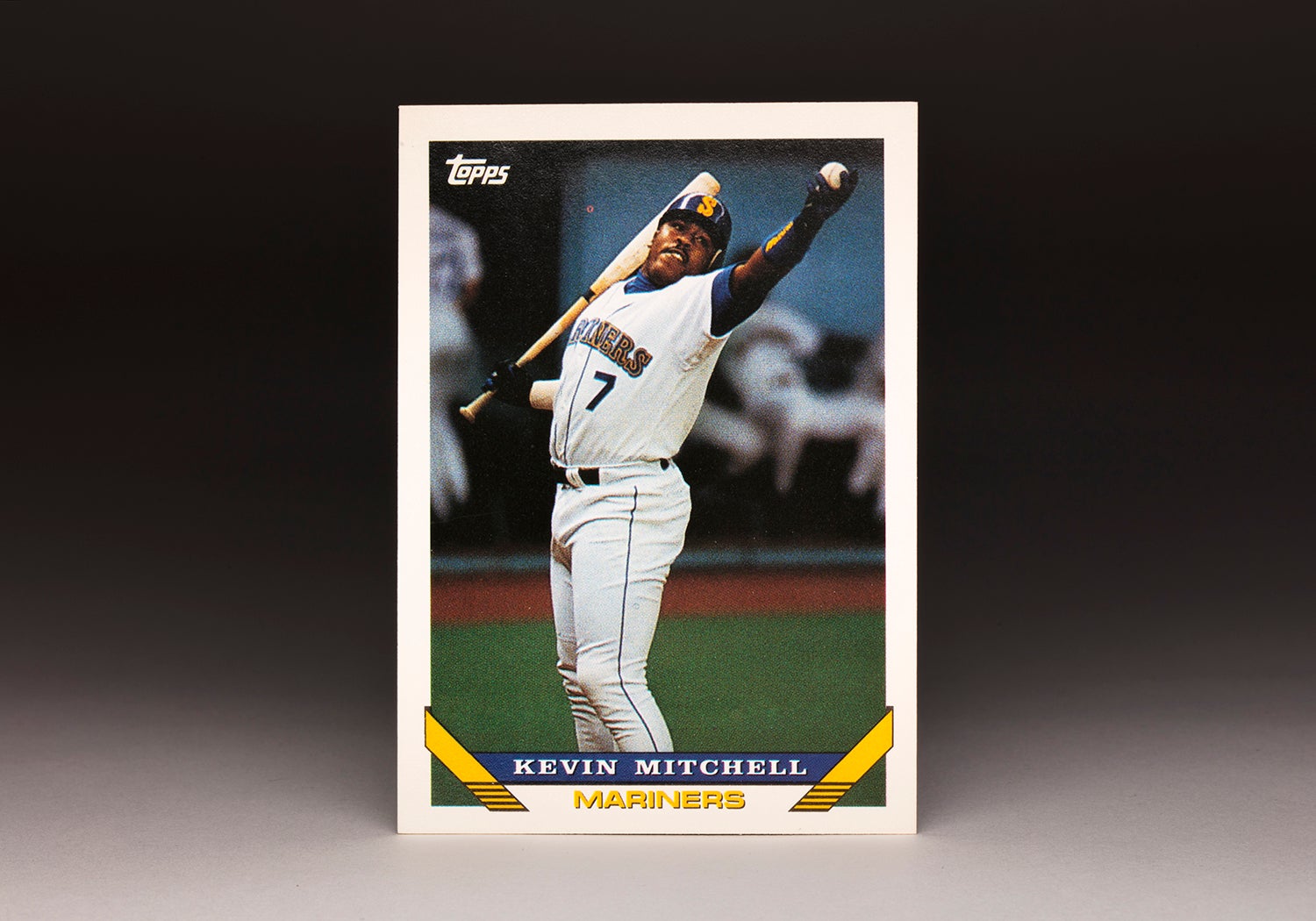

#CardCorner: 1993 Topps Kevin Mitchell

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

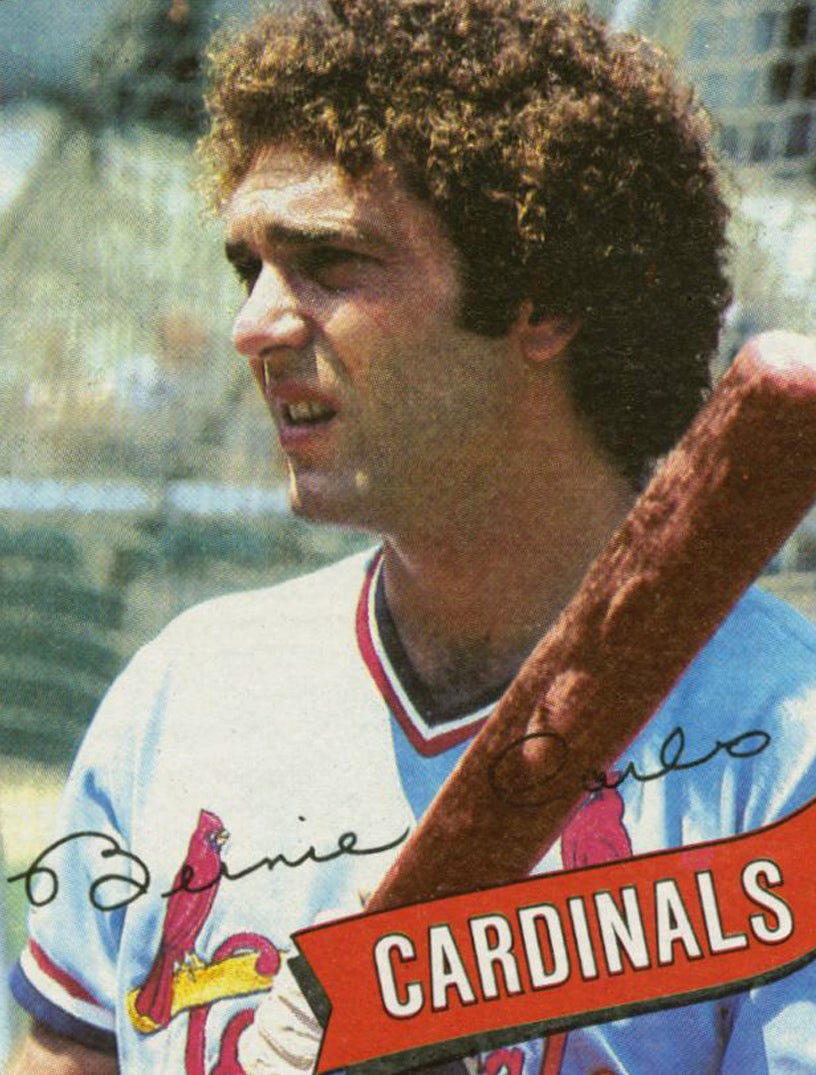

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo