- Home

- Our Stories

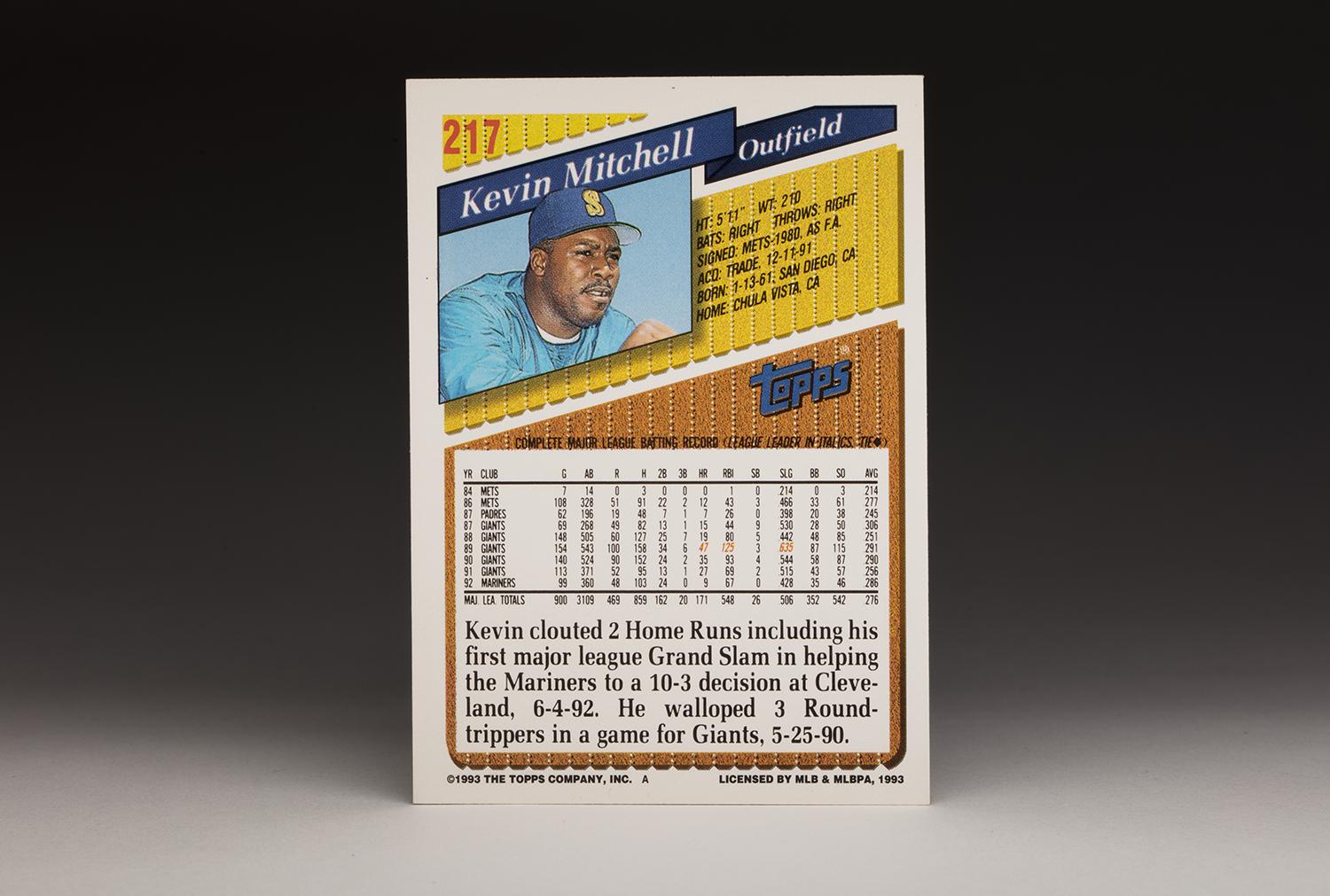

- #CardCorner: 1993 Topps Kevin Mitchell

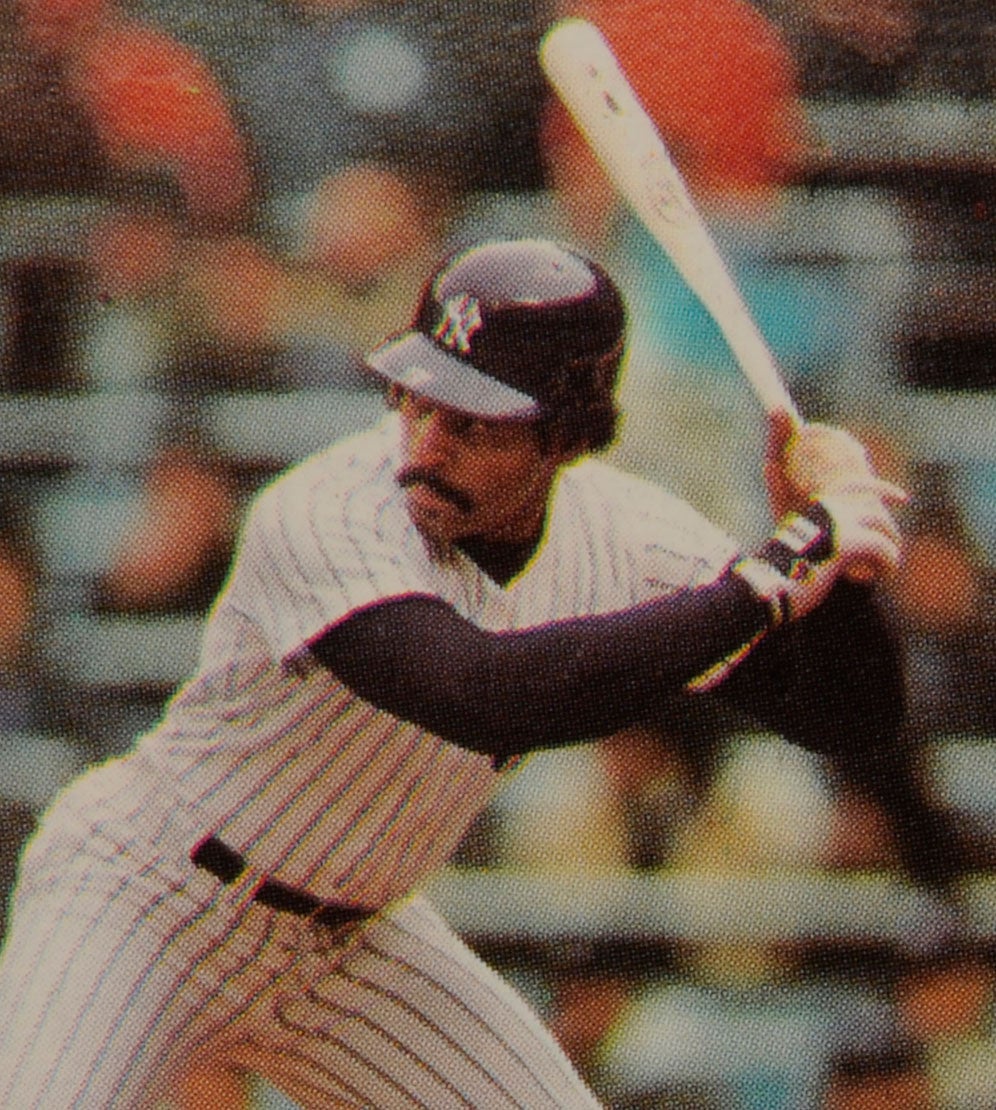

#CardCorner: 1993 Topps Kevin Mitchell

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

I must confess that I’m not sure what Kevin Mitchell is doing on his 1993 Topps card. If I had to guess, I would say that Mitchell is preparing to hit a fungo to one of his Seattle Mariners teammates. Then again, Mitchell is not using a fungo bat, but what appears to be a regulation game bat.

Furthermore, he is leaning so far back that he looks like he could fall over with one wrong move. He’s in an oddly contorted position, one that I’ve never seen from another player on any other card.

It’s also worth noting how Mitchell seems to be holding the ball in his left hand. He appears to be making an exaggerated show of it, as if to indicate to one of his teammates that he’s about to hit a fly ball his way. Or perhaps Mitchell is calling his shot ala The Babe, an unusual tact to take during pregame fungoes.

Whatever the truth, it’s an appropriate image for the unconventional Mitchell, who was often seen in memorable situations and poses on his baseball cards. One of my favorite Mitchell cards is his 1987 Topps card, which shows him completing a slide into home plate, eluding a tag from Montreal Expos catcher Mike Fitzgerald and creating a large cloud of dust for the Topps photographer. Another good one is his 1994 Topps selection, which shows him wearing the sleeveless uniform of the Cincinnati Reds while signing autographs for fans at Riverfront Stadium. And then there’s his 1995 card, which shows him kneeling in the on-deck circle, but leaning so far back that he appears close to losing his balance and falling backward onto the turf.

All of these cards were fitting for Mitchell, a man who did not fit into any of the game’s preconceived notions or stereotypes. Prior to Mitchell’s rookie season with the New York Mets, I had never heard much of a connection between the game and street gangs. That changed with Mitchell, who had grown up on the streets of San Diego, a poor kid from a broken home who became a member of a violent gang. As a youth, Mitchell suffered three gunshot wounds, including one to his leg and one to his wrist. A third gunshot occurred at a carnival when he was all of 14.

“Some guy just walked up in back of me with a sawed off shotgun,” Mitchell told longtime Mets beat writer Jack Lang. “He fired and left a lot of buckshot in my back.” The incident left him with a long, crescent-shaped scar, something that could be seen by teammates each day in the clubhouse.

Not only did Mitchell survive those wounds, but he somehow found a way to continue his baseball endeavors. With his parents separated and Mitchell only two years old, his grandmother, Josie Whitfield, took on the enormous task of raising the young boy. She steered him away from the streets and toward baseball, in part by taking him to Little League games. She would remain with Mitch throughout his career, even advising him about flaws in his hitting mechanics. “You’re front side is opening up too wide,” Mrs. Whitfield would tell her grandson.

Perhaps because of his difficult upbringing in San Diego, Mitchell was not a highly touted player coming out of high school. He played very little ball in high school, instead spending his time on co-ed softball. No major league team drafted him, leaving the Mets the opportunity to sign him as an amateur free agent in 1980. The following summer, they assigned Mitchell to Kingsport of the Rookie League, where he proceeded to torment pitchers to an average of .335. For the most part, Mitchell kept hitting throughout his minor league career.

Then came a road bump in 1984; it turned out to be a nightmarish year for Mitchell because of the death of his stepbrother, Donald. While playing for Triple-A Tidewater, Mitchell learned that Donald had been gunned down in a gangland shooting in San Diego, his body found lying on a set of railroad tracks. Devastated by the news, Mitchell wanted to quit the team and head home. Only the words of two of his teammates, Clint Hurdle and Herm Winningham, convinced Mitchell that he should remain with Tidewater and continue his career.

Distracted by the loss of his stepbrother, Mitchell went into a deep slump that summer. Still, the Mets promoted him in September, giving him his first taste of the major leagues. It was during his first trip to New York that he received a calling card from Mets batting instructor Bill Robinson. An old school coach, Robinson told Mitchell that he had the “worst attitude of any young man that I had ever seen.”

Robinson’s words registered with Mitchell, who began to change his approach toward the game. Two years later, Mitchell came back to New York, this time leaving the minor leagues for good. I happened to be living in New York in 1986, and remember hearing little about Mitchell at the time. He was not a heralded prospect, not a “can’t miss” phenom like a Darryl Strawberry or a Dwight Gooden.

Additionally, Mitchell brought an unusual appearance, thick and muscular, to the leisurely game of baseball. He did not look like anyone else in the game. Big and burly, Mitchell looked like he should be playing linebacker for the New York Jets or fullback for the New York Giants, not a finesse game like baseball.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Against the odds, Mitchell managed to make the Mets’ Opening Day roster. Mitchell’s first manager, Davey Johnson, took an immediate liking to the young slugger. Johnson did not care about appearances or stereotypes. He just knew that Mitchell could hit, while giving the Mets depth at six different positions, including hard-to-fill spots like shortstop and third base. If someone needed a day off, Johnson could plug Mitchell into that position and expect a few lethal swings accompanied by a hit or two, often for extra bases.

Mitchell became an important part of a great Mets team in 1986. Playing six different positons, including his more accustomed left field, he hit .277 with 12 home runs in 108 games. Mitchell did so well that he received ample support in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting, finishing third behind reliever Todd Worrell and second baseman Robby Thompson.

At only 24 years old, Mitchell should have had a long career in New York. Unfortunately, the Mets’ front office did not share the same optimistic view. Not forgetting his street gang background, the Mets’ brass worried that Mitchell would cause problems, either for himself or team chemistry. They felt he might be a bad influence on other young players. That’s why they included him in a blockbuster deal with Mitchell’s hometown San Diego Padres, who took him as part of a package for All-Star outfielder Kevin McReynolds.

The Padres made Mitchell their Opening Day third baseman, but he flopped in San Diego. Not only did he struggle to hit, but he also clashed with manager Larry Bowa, a hardline sort who believed in discipline far more than Johnson. Mitchell also began to associate with some of the bad elements in San Diego, friends of his that remained gang members. By July, the Padres realized that the decision to bring him back to San Diego was not a good one. So on July 5, the Padres announced a massive trade, sending Mitch and left-handed pitchers Dave Dravecky and Craig Lefferts to the San Francisco Giants for third baseman Chris Brown and a parcel of pitchers.

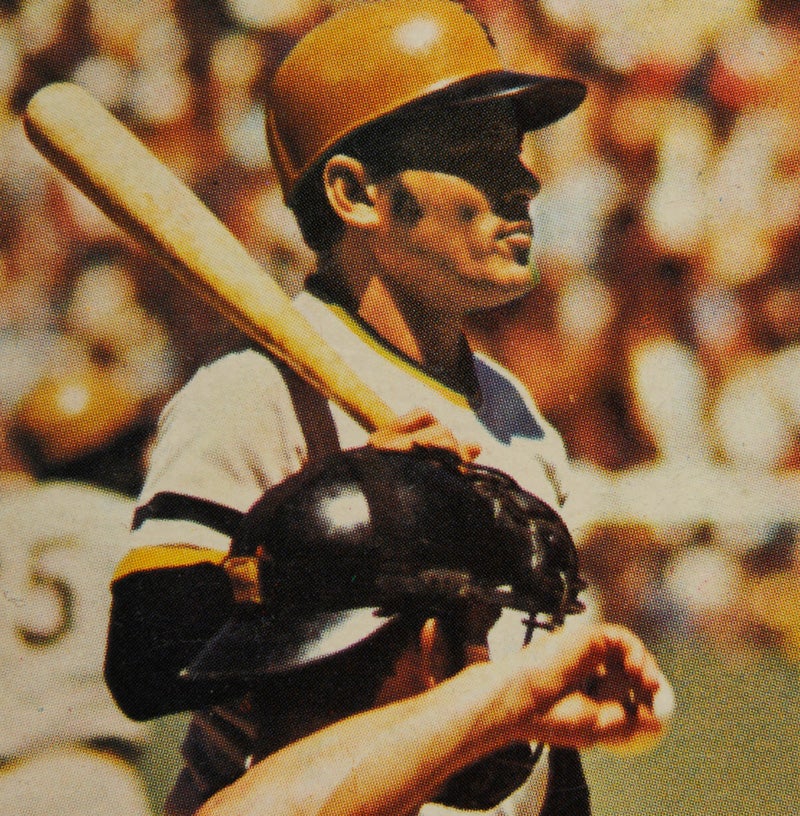

Mitchell found a comfort zone in San Francisco, where he enjoyed the benefit of a player’s manager like Roger Craig. By 1989, he had become a star. That summer, Mitchell led the Giants to the National League Western Division title and led the NL in just about everything: Home runs, RBIs, slugging percentage, OPS, and total bases. For the first time in his career, he made the All-Star team. And he took home the MVP Award, beating out his talented teammate, Will Clark. Some writers referred to the tandem of Mitchell and Clark as the best hitting duo in the major leagues.

A few of his former teammates noticed a change in Mitchell’s game. “Mitchell is so much quicker with the bat than he used to be,” one Mets pitcher said anonymously in an interview with Bob Klapisch of the New York Daily News. “I heard in the past you could get the ball by him up and in. Not this year.”

That same year, Mitchell made national highlight reels when he tracked a fly ball by Ozzie Smith into the darkness of the left-field corner at Busch Stadium, temporarily overran the play, and then made a remarkable catch with his right hand, his bare hand. The play drew a shocked reaction from ballpark observers, including Giants catcher Terry Kennedy, who could be seen laughing openly in disbelief. It’s a play that can easily be found on Internet video, a play that is still fondly remembered nearly 30 years later.

A well as Mitchell played for the Giants in 1989 and into the early 1990s, the Mets were not completely wrong about him. Developing a reputation as someone who sometimes showed up late to the ballpark, Mitchell became a divisive influence in the clubhouse. His difficult upbringing in San Diego also appeared to contribute to some violent behavior. In 1999, Mitchell confronted his father, an alcoholic, after he pawned his 1986 World Series ring. The two men became engaged in a nasty argument, Mitchell threw his father off the property, and ended up getting arrested for assault. One year later, while playing in independent minor league ball, Mitchell became involved in a bench-clearing brawl and actually punched out the owner of the opposing ballclub. That incident brought Mitchell a nine-game suspension.

Mitchell could be colorful in a lighter way, too. He became known by the nickname of “Boogie Bear,” a tribute to his fun-loving ways. He liked to wear crocodile-skin combat boots, valued at roughly $1,800. He also collected vehicles; at one point, he had 11 all-terrain vehicles, a pair of dune buggys, two pickup trucks, two utility trailers, a Humvee, and a 1964 Chevy convertible.

Even Mitchell’s health seemed to be governed by offbeat forces, as he developed a penchant for sustaining injuries in bizarre ways. On one occasion, he suffered a strained ribcage while vomiting. Another time he put some eyewash into his eye, unaware that someone had put rubbing alcohol in the bottle; that resulted in some nasty burning. He also broke a tooth after taking a bite out of a donut that he had overheated in a microwave. The circumstances of some of the injuries were often funny, but they became less amusing in the context of his chronic inability to stay healthy. Often overweight, Mitchell simply could not keep himself away from the disabled list. As Mitchell aged into his 30s, he became more and more brittle, just like the tooth that met its match from the overheated donut.

Injuries and controversies sapped potential superstardom from Mitchell. He had a fine career, putting up huge numbers for the Giants in 1989, ’90, and ’91, and earning two All-Star Game selections. But once he reached the age of 30, he never appeared in more than 99 games in a season. His conditioning left something to be desired; at one point, he put on 40 pounds, topping out at roughly 250 pounds. Still, he hit very well for the Reds, capped off by a 1.110 OPS in 1994, but the season-ending strike limited him to only 95 games. The Reds allowed him to become a free agent, but rather than sign with another big league team, he took his talents to Japan for a season. After only 130 at-bats for the Daiei Hawks, he suddenly left the team in a dispute over whether the condition of his knee would allow him to play.

In 1996, Mitchell returned to the major leagues with the Boston Red Sox, but soon found himself on the move again, this time traded back to the Reds. As with Boston, Mitchell hit well for the Reds, but he could no longer play a position in the field. Without the DH option in the National League, it became difficult for Mitchell to find playing time. That’s why the Reds allowed him to hit free agency that winter.

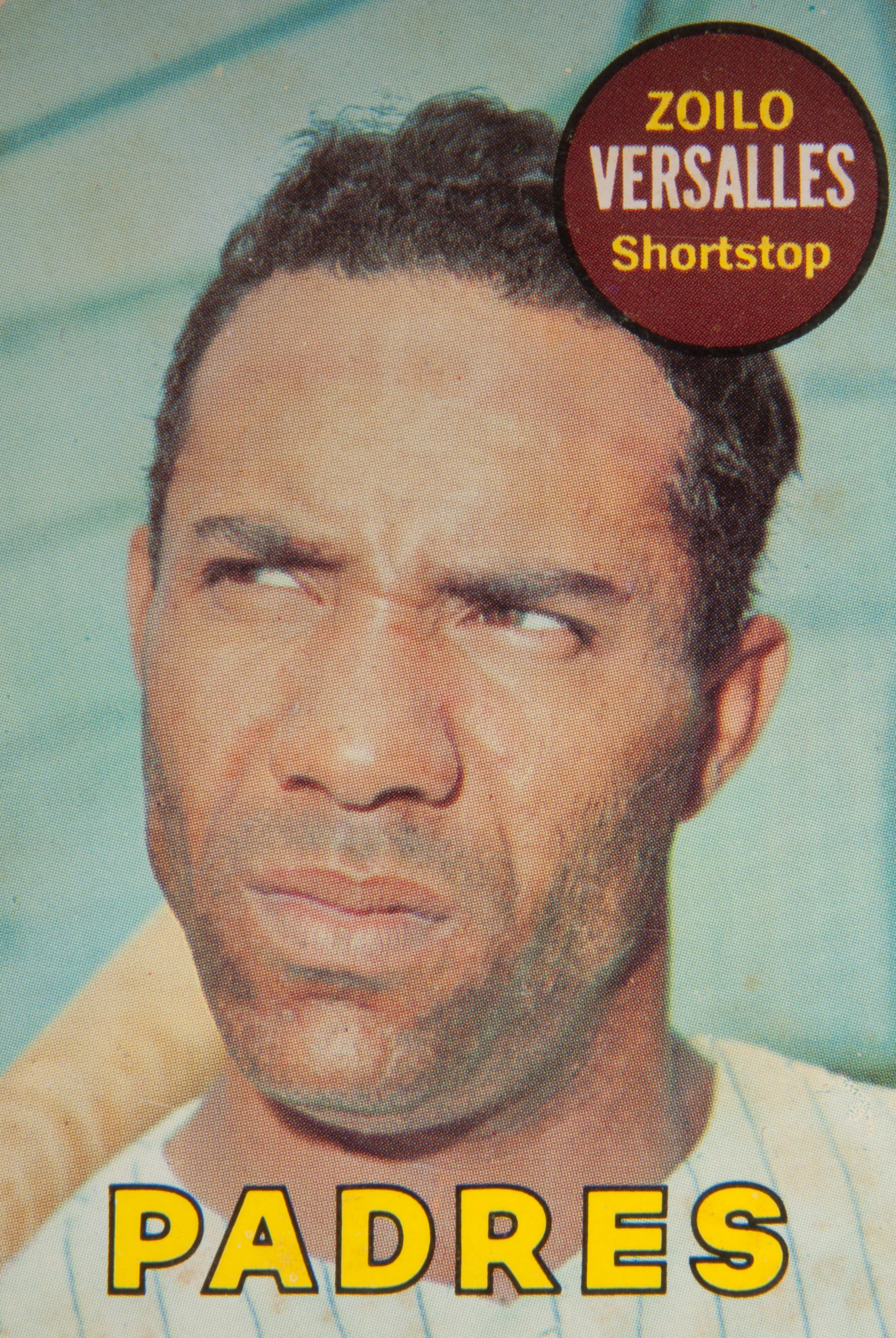

Bill Robinson, a former outfielder, first baseman and third baseman, gave Kevin Mitchell the wake-up call he needed while Robinson was serving as a batting instructor for the Mets. After Robinson referred to Mitchell as having the "worst attitude of any young man that I had ever seen," Mitchell changed his behavioral approach to the game. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

Davey Johnson, pictured above, took an immediate liking to Kevin Mitchell because of his prowess at the plate. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

After an 1989 season in which Kevin Mitchell narrowly beat out teammate Will Clark (pictured above) for the National League MVP Award, the two players were viewed as one of the best hitting duos in the major leagues. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

Over his final two seasons, Mitchell bounced from Cleveland to Oakland, but failed to hit in either spot. At 36, he was done as a big leaguer and looking for work in the Mexican League, leaving many observers wondering how productive he might have been had he kept himself in better shape and avoided the bug of injuries.

Now the owner of a barber shop, Mitchell has seen his physical health change him in another way. In 2008, he was diagnosed with diabetes. Mitchell said the diagnosis changed his attitude, making him committed to improve his own health while also helping others. Losing 40 pounds in a matter of few weeks, Mitchell decided to become a big brother to troubled inner-city youths.

As part of his work for the non-profit “Athletes for Education,” he has counseled children against the pratfalls that he had encountered while growing up in San Diego. He also gives free batting instruction to 10 and 11-year olds at the Brickyard batting cages in San Diego.

For many in baseball, Mitchell’s epiphany comes as a welcome surprise. Some believed that Mitchell would die young, becoming victim to the tough lifestyle that he first learned growing up in San Diego. But he’s overcome that, along with a diagnosis of diabetes, and seems to have found his way.

It hasn’t been easy, but Kevin Mitchell has survived.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

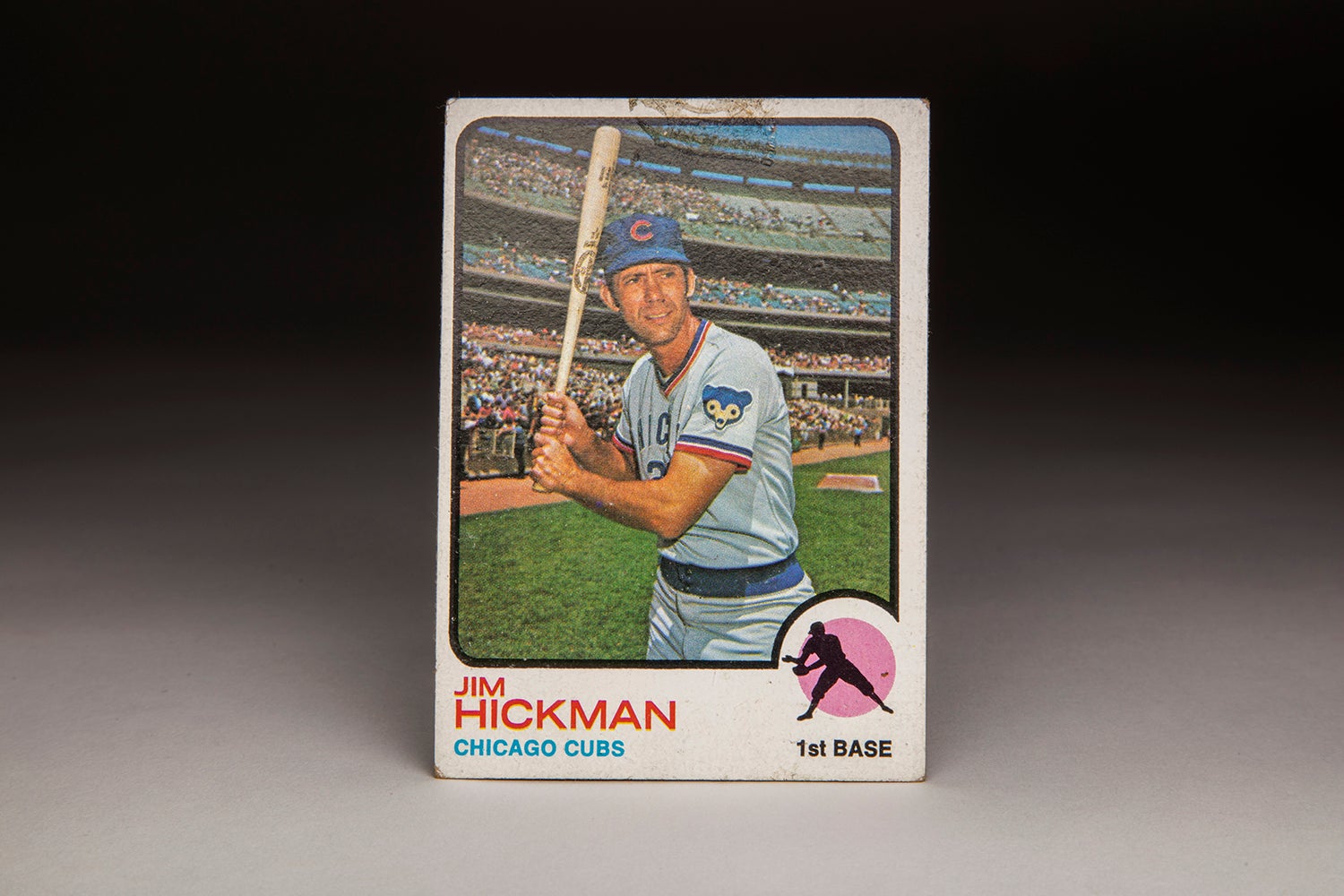

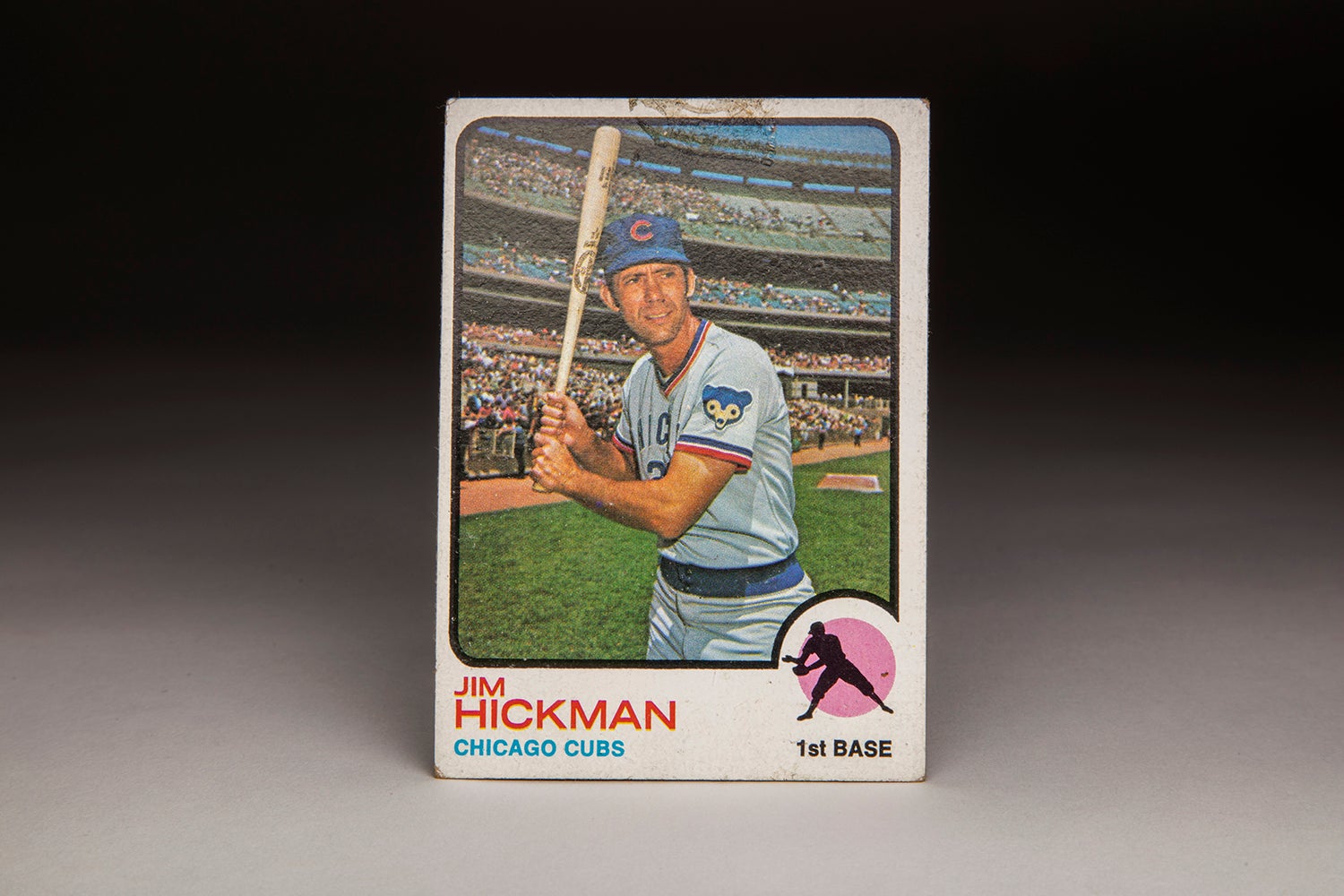

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

1963 Hall of Fame Game

Gary Herrmann - A King in Queen City

Ready for the Weekend

#CardCorner: 1993 Topps Kevin Mitchell

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Pagliarulo

#PopUps: Meb's First Pitch

Remembering Joe Garagiola

Treasures from Cooperstown Coming to Capital Region for Tri-City ValleyCats Game on Wednesday

01.01.2023