- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1991 Upper Deck Ron Gant

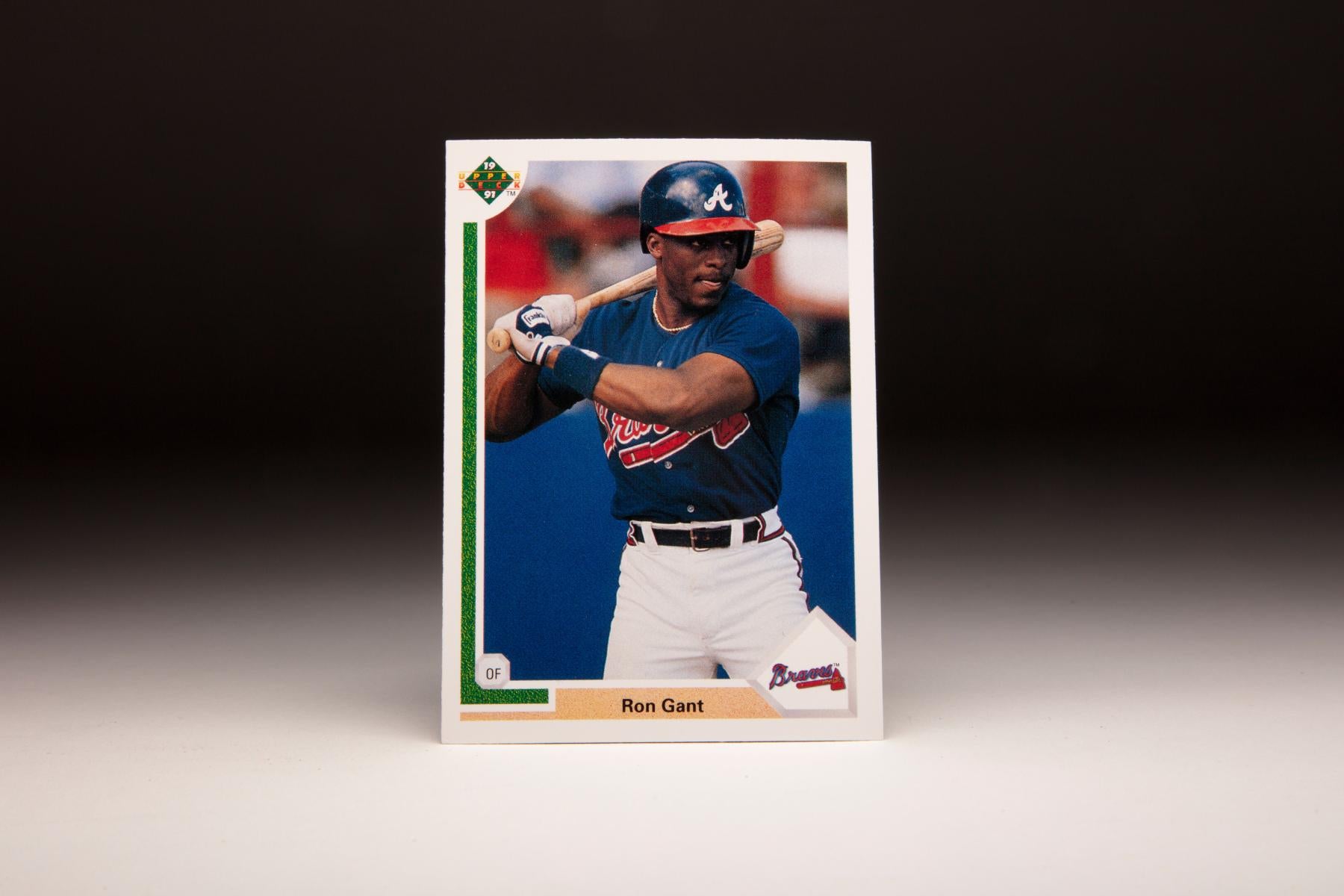

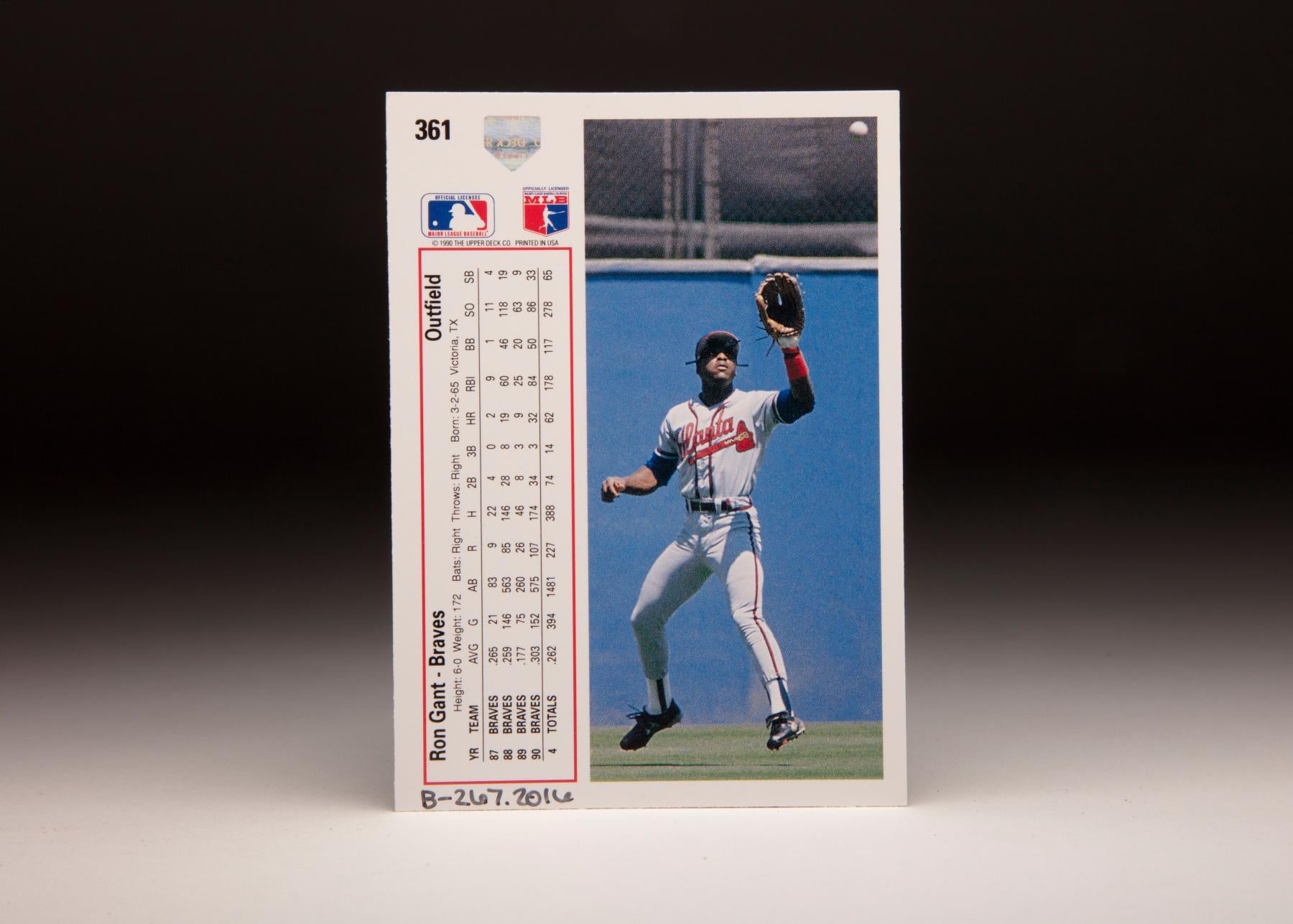

#CardCorner: 1991 Upper Deck Ron Gant

He became only the third player in history with back-to-back 30 homer/30 steal seasons, and Ron Gant remains one of only seven to reach that level in consecutive years.

And while he did not become the face of the franchise his talent may have predicted, Gant carved out an Atlanta Braves legacy before helping three other teams reach the postseason.

Born March 2, 1965, in Victoria, Texas, Gant excelled in youth sports and played shortstop for Stroman High School in Victoria before a family move across town landed him at Victoria High School for his junior and senior seasons.

“Ronnie is a pressure player,” Victoria coach Robert Tripson – a man Gant often described as more of a father than a coach – told the Victoria Advocate after Gant led the Stingarees to a win over Stroman in a critical game during the spring of 1982.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

But though Gant batted over .500 for much of his junior season, his defense – he moved from shortstop to third base when he switched schools – was a work in progress that included a four-error game. But Gant returned to shortstop as a senior and hit .424 with five home runs and 19 steals, earning the team’s Most Valuable Player Award.

On June 7, 1983, the Braves took Gant in the fourth round of the MLB Draft.

“Gant is very quick and fast,” Braves scout Charlie Smith told the Advocate, “and there is a distinction. Gant…can play the interior of the infield, and players like that are hard to find.

“You could tell that Ronnie was born to be a major league player.”

Gant quickly signed and reported to the team’s Gulf Coast League affiliate that summer, hitting .233 in 56 games. He moved up to Class A Anderson of the South Atlantic League the next season and hit .237 with little power – and the Braves sent him back to the same league in 1985, this time with Sumter.

After hitting .256 with 19 steals in 102 games, Gant was invited to the Braves fall instructional league post in West Palm Beach, Fla. There, he was involved in an altercation with fellow players and others at a local night spot, and in the melee Gant was shot in the left leg in the parking lot.

“I was in the wrong place at the wrong time, exactly,” Gant told the Atlanta Constitution. “By that happening, I worked really hard with weights to get my leg back in shape. When I started getting in shape, I felt strong. I worked it so much. My upper body was strong because it was the first time I’d really lifted weights. I felt like Superman.”

With his newfound strength, Gant tore up the Carolina League at Durham in 1986, batting .277 with 26 homers, 102 RBI and 35 steals to earn the Braves’ Minor League Player of the Year Award. He hit .247 with 14 homers, 82 RBI and 24 stolen bases for Double-A Greenville in 1987 to earn a late-season promotion to the big leagues, where he hit two homers and stole four bases in 21 games.

His first career home run came against 40-year-old Nolan Ryan, who was en route to NL-best marks in ERA (2.76) and strikeouts (270).

Gant started the 1988 season with Triple-A Richmond, but after hitting .311 over 12 games he was brought back to Atlanta.

“Ronnie’s played well for us before, and we think he’s ready,” Braves general manager Bobby Cox told the Constitution. “We don’t think this is rushing him. This will help us.”

Gant proved to be ready for the challenge, leading all big league rookies in 1988 with 19 home runs, 60 RBI, 85 runs scored, eight triples and 55 extra base hits. But 31 errors, including 26 in 122 games at second base, may have soured some NL Rookie of the Year voters – and he finished fourth in the balloting behind Chris Sabo, Mark Grace and Tim Belcher.

“Ron’s one of our foundation players,” Braves manager Russ Nixon told the Advocate. “We maybe brought him up a year too soon. But he came through with flying colors.”

Gant’s play as a rookie immediately caught the attention of the Braves’ marketing team, which put him on the cover of the club’s 1989 media guide. But Gant’s struggles in the field necessitated a move to third base to start the 1989 season.

“It’s a good feeling knowing the organization likes me as a player and a person,” Gant told the Advocate. “I like playing third base. I’d like to play there the rest of my career. But wherever they want to put me, I’ll play. I’ll do anything as long as it helps us get some (wins).”

Gant worked on his new position in the Puerto Rican Winter League, but he soon clashed with Nixon after the errors and strikeouts piled up. Hitting .172 with 16 errors through 60 games, Gant was sent to Class A Sumter to learn how to play the outfield on June 21, 1989.

“I didn’t get along with the manager,” Gant told the Constitution. “But the manager didn’t go out to play third base and make errors and not hit. That was my fault.”

After two weeks in Class A ball, the Braves promoted Gant to Triple-A Richmond before bringing him back to Atlanta in September. This time, Gant was stationed in center field.

He finished the year hitting .177 in 75 games with the Braves, then rededicated himself to the weight room and added 11 pounds of muscle in the offseason.

“I felt I had to do something,” Gant told the Palm Beach Post in Spring Training. “I did it for my confidence.”

Gant began the 1990 season in a bench role but began finding traction in early May. By June 3, Gant was hitting .349 as the Braves’ starting center fielder. But Atlanta lost 40 of its first 65 games, prompting Cox to dismiss Nixon and take over the managerial duties himself. Cox kept Gant in center field – and though Gant cooled down during the heat of the Atlanta summer, he still finished with a .303 batting average, 107 runs scored, 32 homers, 84 RBI and 33 steals.

The Braves finished in last place in the NL West with a record of 65-97. It would be the last time the team finished out of playoff position for 15 seasons.

In 1991, Gant’s batting average dropped more than 50 points but his other numbers remained strong as he hit .251 with 101 runs scored, 32 homers, 105 RBI and 34 steals – finishing sixth in the NL MVP race and winning a Silver Slugger Award. Batting out of the third, fourth or fifth spot in the order for most the year, Gant powered the Braves to a worst-to-first run that saw them win the NL West title for the first time in nine seasons.

In his first postseason action, Gant hit .259 with a homer, four runs scored and seven stolen bases in the Braves’ seven-game win over the Pirates in the NLCS. In Game 7, Gant’s first-inning sacrifice fly scored Lonnie Smith to give Atlanta the only run it would need in a 4-0 victory, and his seven steals set a record for a player in the NLCS.

In the World Series vs. the Twins, Gant batted .267 with four RBI, including a run-scoring groundout in the seventh inning of Game 6 that tied the game at 3. But with the Braves one run from a title, Kirby Puckett homered in the bottom of the 11th to force Game 7, and Jack Morris’ 10 shutout innings the next night gave Minnesota the championship.

Morris retired Gant with two men on in both the third and fifth innings to end Atlanta scoring threats.

The Braves and the Pirates met again in the NLCS in 1992 following a season where Gant hit .259 with 17 homers, 80 RBI and 32 steals. Despite failing in his pursuit of a record third straight 30/30 season, Gant – who moved to left field that year – was named to his first All-Star Game.

In the NLCS, Gant’s fifth-inning Game 2 grand slam off Pittsburgh’s Bob Walk gave Atlanta an 8-0 in an eventual 13-5 win, and his ninth-inning sacrifice fly in Game 7 cut the Pirates’ lead to 2-1 in a contest that was eventually decided on Francisco Cabrera’s two-run, two-out, pinch-hit single in the ninth inning.

“Right now, I’m swinging the bat as well as any time in my career,” Gant told the Associated Press during the NLCS as he emerged from a slump that saw him bat .199 from June 8 through Sept. 9. “It took a lot of hard work.”

But in the World Series, Cox elected to go with Deion Sanders as his starting left fielder in Games 2, 3, 5 and 6 – and Gant hit just .125 in four games in the Braves’ six-game loss to Toronto.

Gant redoubled his training efforts in the offseason, adding another 10 pounds of muscle to his already sculpted frame – reporting to camp at 205 pounds. But what he found in camp was the same logjam that existed in the World Series, with Sanders, Otis Nixon and Dave Justice all fighting for time with him in the outfield.

“My attitude is I’m not going to let anything stop me,” Gant told the Palm Beach Post. “My free agent year is next year. This is my most important year and I’m not going to let anything stand in the way.”

Gant was as good as his word, putting together his best season with a .274 batting average, 113 runs scored, 36 homers, 117 RBI and 26 steals. He finished fifth in the NL MVP voting as the Braves won another NL West title before falling to Philadelphia in the NLCS.

Gant and the Braves came to an agreement on a one-year, $5.5 million deal for the 1994 campaign. But on Feb. 3, 1994, Gant broke two bones in his right leg in a dirt bike accident. The Braves then chose to release Gant rather than risking him miss the season, playing him about one sixth of the contract in termination pay.

Suddenly, one of the game’s top players was on the open market.

On June 21, 1994, the Cincinnati Reds signed Gant to a two-year deal that was worth the minimum salary for 1994 and then as much as $3.5 million in 1995. But Gant was not yet healthy enough to play by the time the strike ended the season, wiping out his entire 1994 campaign.

Gant returned to full strength the next season, hitting .276 with 29 homers, 88 RBI and 23 steals as the Reds won the NL Central title. Gant hit .231 with a homer, two RBI and three runs scored in the Reds’ sweep of the Dodgers in the NLDS. But against his old teammates in the NLCS, Gant hit just .188 as Cincinnati was swept by Atlanta.

Following the season, Gant signed a five-year deal with the Cardinals. He hit 30 home runs in 122 games in his first season in St. Louis but suffered a torn rotator cuff in his left (non-throwing) shoulder in late August. Still, Gant managed to play through the injury and helped the Cardinals advance to the NLCS, where they fell to the Braves in seven games. Gant hit .286 with three homers and eight RBI in 10 postseason games that year.

“Ron definitely is a vital part of this ball club,” Cardinals shortstop Royce Clayton told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He’s a team leader.”

But Gant began the 1997 season in a protracted slump and never heated up, finishing the season with a .229 batting average, 17 homers and 62 RBI in 139 games. He bounced back in 1998 with 26 homers and 67 RBI in 121 games – but the Cardinals traded him to the Phillies on Nov. 19 – along with Jeff Brantley and Cliff Politte – in exchange for Ricky Bottalico and Garrett Stephenson.

“We think (Gant) can give us 30 home runs,” Phillies general manager Ed Wade told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Gant missed that mark, but scored 107 runs on the strength of a .364 on-base percentage while hitting 17 homers and driving in 77 runs. Gant hit 20 home runs in his first 89 games in 2000 before the Phillies dealt him to the Angels at the trade deadline – and Gant finished the season with 26 homers and 54 RBI.

A free agent once again, Gant signed a one-year deal worth a reported $2.05 million with the Rockies on Dec. 10, 2000. Now a bench player at age 36, Gant hit .257 with eight homers in 59 games before being traded to the Athletics on July 3, 2001. The A’s were two games under .500 at the time of the trade, but afterward Oakland went an incredible 62-18 to win the AL Wild Card before losing to the Yankees in the ALDS.

Gant hit .259 with the A’s over 34 games and added a homer in the postseason.

He returned to the National League in 2002 with the Padres, hitting .262 with 18 homers in 102 games.

On the eve of Spring Training in 2003, Gant signed a minor league deal to return to the A’s.

“I knew I could still play somewhere,” Gant told Scripps Howard News Service. “After the year I had last year I thought: ‘This is how I’m rewarded?’ I was more upset than anything.

“I never wanted to leave here (after the 2001 season). I’m sure anybody would want to play here. They always seem headed in the right direction.”

The A’s won 96 games in 2003 and captured the AL West title, but Gant was not around to see it. After hitting .146 in 17 games, the Athletics released Gant on June 4.

He would not play organized ball again. But Gant had a second career ahead in broadcasting, joining the Braves’ TV crew in 2004 and later becoming a newscaster for WAGA-TV in Atlanta.

He finished his 16-year playing career with a .256 batting average, 321 homers, 243 stolen bases, two All-Star Game selections and six appearances in the postseason. And though he never repeated his 30/30 performances of 1990-91, Gant left a reputation as one of the most athletic players of his generation.

“I think I have the kind of potential to be a 40-40 kind of guy, to do something that would get me into the Hall of Fame,” Gant said early in his career. “The ultimate goal is to get into the Hall of Fame.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps John Tudor

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Don Buford

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Doug DeCinces

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps John Tudor

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Don Buford

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Doug DeCinces