- Home

- Our Stories

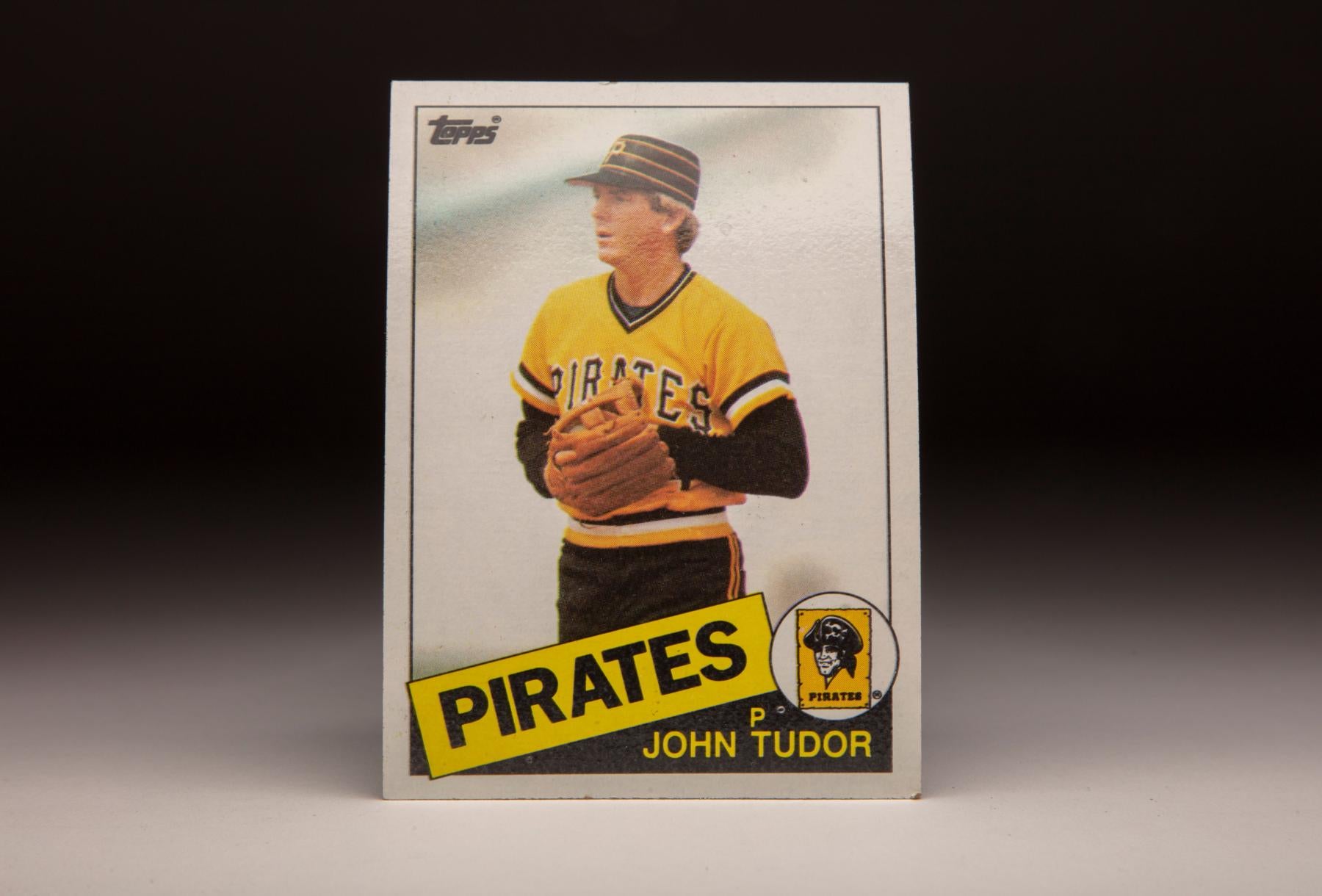

- #CardCorner: 1985 Topps John Tudor

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps John Tudor

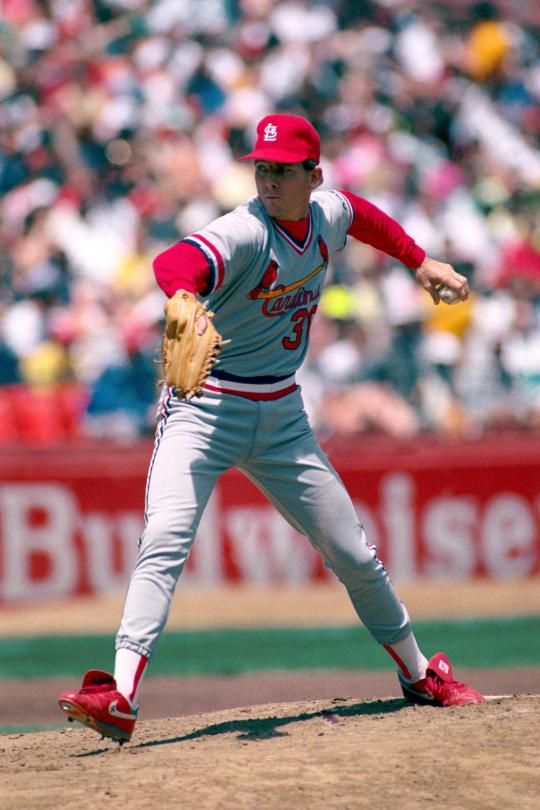

Over 26 starts in the last four months of the 1985 season, John Tudor was nearly untouchable.

Consider Tudor’s 20-1 record, 1.37 ERA, 0.871 WHIP and 10 shutouts over those 210 innings. Maybe Lefty Grove in a similar period in 1931 (23-3, 2.19 ERA) was better. Maybe Sandy Koufax in 1963 (18-3, 2.00). Maybe Bob Gibson in 1968 (19-4, 0.96).

Maybe. But maybe John Tudor’s stretch was the best of them all.

“He’s something, isn’t he?” Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog told the Associated Press. “He’s the best or second-best there is. Let’s say he’s the best left-hander.”

Herzog’s qualification on Tudor’s performance was in deference to Mets ace Dwight Gooden, who was on his way to a 24-4 season and the 1985 National League Cy Young Award. And though Gooden was the unanimous winner, many observers felt Tudor’s effort may have been more impressive – given Tudor accomplished it all with a fastball that rarely topped 85 miles an hour.

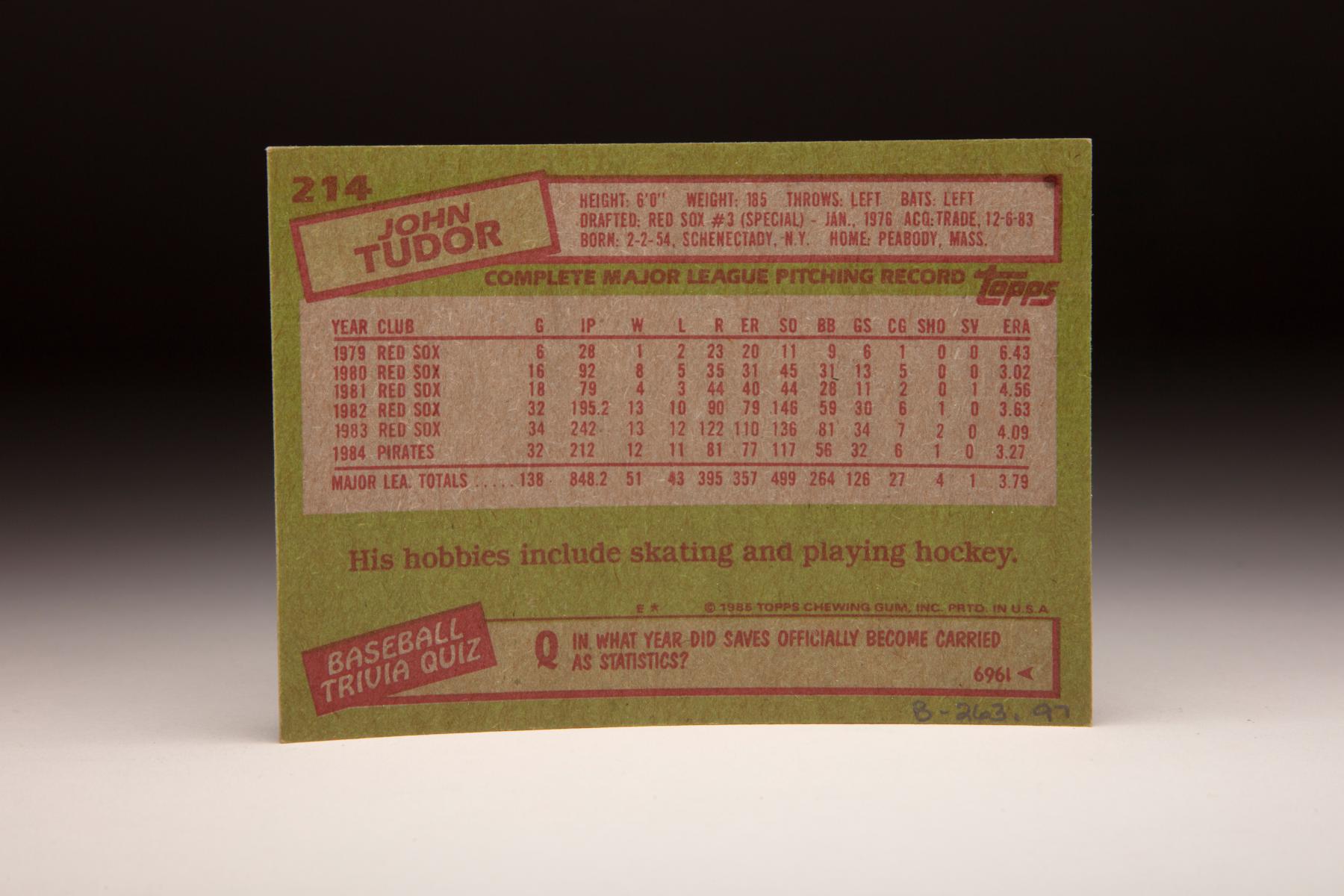

Born Feb. 2, 1954, in Schenectady, N.Y., Tudor was raised in the Boston area. He played hockey, basketball and baseball at Peabody High School before enrolling at North Shore Community College in Danvers, Mass. From there, Tudor pursued his dreams at Georgia Southern University, where he made the team as a walk-on.

After a successful spring season in 1975, Tudor was picked for a U.S. team that played in People-to-People International Games in Colombia. By now, he was on the radar of big league teams – and the Mets selected Tudor in the 21st round of the June 1975 MLB Draft. Tudor did not sign, but was draft-eligible again in the January 1976 Secondary Phase MLB Draft, where he was taken by the Red Sox in the third round.

This time, Tudor signed. Of the 56 players selected ahead of him, only Hubie Brooks compiled a big league career WAR of better than 10.0. Tudor finished his 12-season career with a mark of 34.2.

Tudor’s first stop in the minor leagues was with Class A Winston-Salem in 1976, where he went 5-2 with a 2.74 ERA – mostly out of the bullpen. He was promoted to Double-A Bristol of the Eastern League the following year, where he was 6-5 with a 3.52 ERA before a late-season promotion to Triple-A Pawtucket.

Tudor spent the entire 1978 season in Triple-A, going 7-3 with a 3.09 ERA as a starter and reliever – earning himself an invitation to Spring Training in 1979.

“Boy, he’s got a good fastball,” Red Sox manager Don Zimmer told the Boston Globe after watching Tudor in an exhibition game. “He’s got that nice, easy motion. (He) flips the ball and really gets it up there in a hurry.”

Tudor had pitched winter ball in the Dominican Republic following the 1978 season and developed a sore arm. And though he didn’t make the Red Sox Opening Day roster in 1979, he regained his velocity during the spring, going 10-11 with a 2.93 ERA with Pawtucket before he was called up to Boston in August.

Tudor made his big league debut on Aug. 16 against the White Sox, and after allowing 20 earned runs in 21 innings in his first five starts, Tudor picked up his first win in his last game of the season – permitting just one unearned run over seven innings Sept. 21 vs. Detroit.

Tudor was the only left-hander to start a game on the mound for the Red Sox in 1979, as prevailing opinion said that the Red Sox – with half their games at Fenway Park and its inviting left field wall for right-handed batters – were better off with right-handed pitchers on the mound.

He began the 1980 season back in Pawtucket and was recalled in June after going 4-5 with a 3.65 ERA in 12 games. He dealt with a sore left shoulder for most of the rest of the season but still went 8-5 with 3.02 ERA, inserting himself into the discussion for the Red Sox’s rotation in 1981.

“I realize I’m at a crossroads of my career,” Tudor said during the 1980 season. “If I pitch well, I’ll make it. If I don’t, they’ll probably put on my tombstone: ‘Just another left-hander who died in Fenway Park.”

Tudor won a spot in the Red Sox’s rotation in 1981 but was scuffling with a 2-3 record and 4.11 ERA when the strike hit in June. After two more rough starts in August, Tudor was moved to the bullpen – and he finished the year with a 4-3 record and 4.58 ERA.

But Boston manager Ralph Houk believed in Tudor’s talent. And Tudor was once again in the Red Sox’s rotation to start the 1982 season.

“I’m trying to make him realize just how good an arm he has,” Houk told the Tampa Tribune during Spring Training. “And the big thing for him is to get ahead of the hitters. They don’t hit him much when he gets ahead.”

Tudor shut out the Orioles in Boston’s third game of the 1982 season and completed his first full year as a regular starter with a 13-10 record and 3.63 ERA over 195.2 innings. In 1983, Tudor led all Red Sox pitchers with 242 innings pitched while going 13-12 with a 4.09 ERA.

But with fellow lefties Bruce Hurst and Bob Ojeda also in the rotation, the Red Sox felt they could afford to trade some pitching. So on Dec. 6, 1983, Boston shipped Tudor to Pittsburgh in a one-for-one trade for outfielder Mike Easler.

“You hate to give up a pitcher of Tudor’s quality,” Houk told the Associated Press. “But we need some left-handed punch, and we think Easler’s got it.”

Easler would post two very productive seasons with the Red Sox, including hitting .313 with 27 homers and 91 RBI in 1984 as Boston’s everyday DH. Tudor, meanwhile, joined a Pittsburgh team long on starting pitching but short on bats.

“The pleasing thing,” Tudor told the Pittsburgh Press after his first outing for the Pirates, a 3-1 win over the Dodgers on April 6, “is that to get what (the Red Sox) wanted, they had to trade me.”

But Tudor and the Pirates endured a strange season in 1984 where Pittsburgh led the big leagues with a 3.11 ERA and outscored opponents by 48 runs but still finished last in the NL East with a record of 75-87. Tudor was 12-11 with a 3.27 ERA over 212 innings.

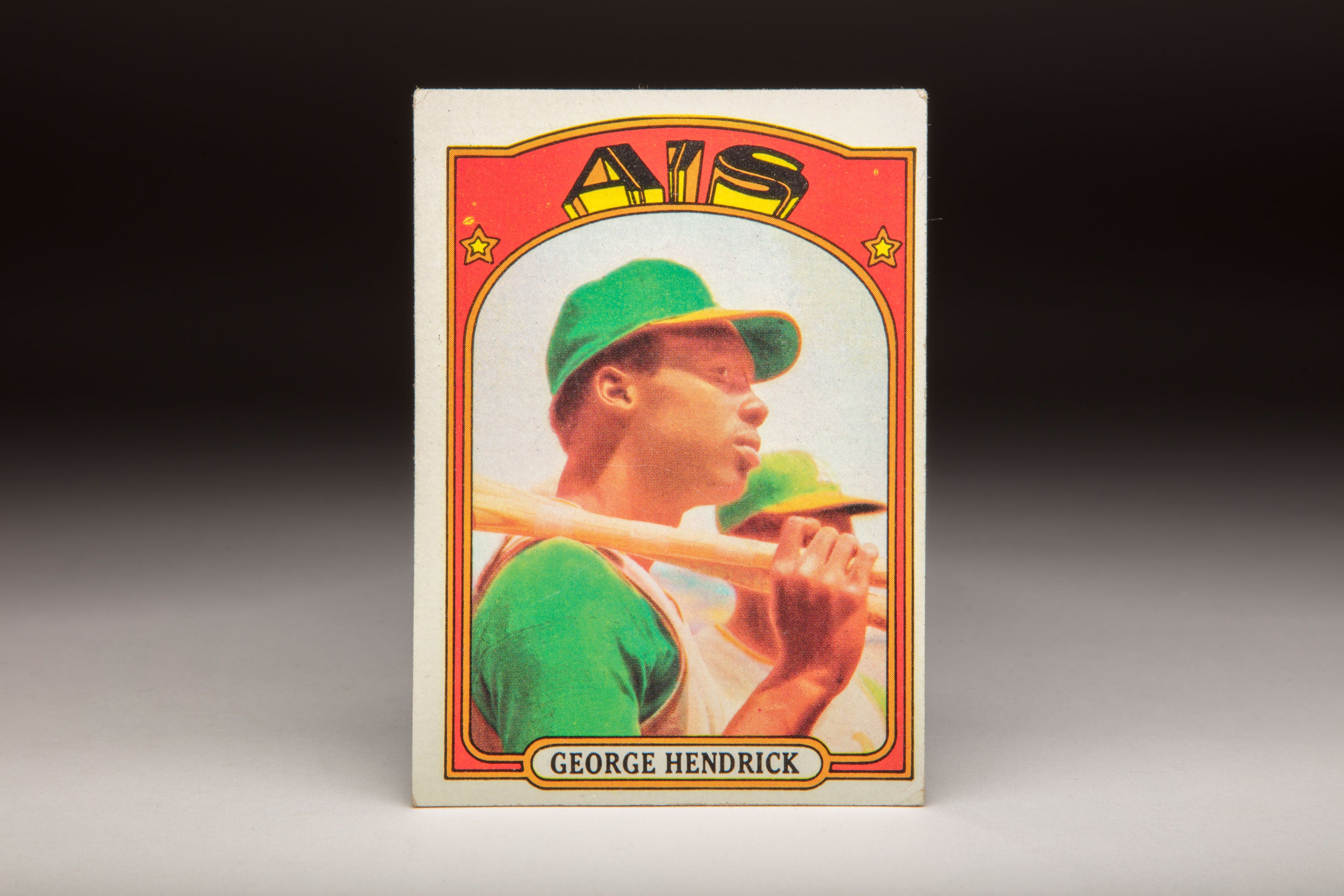

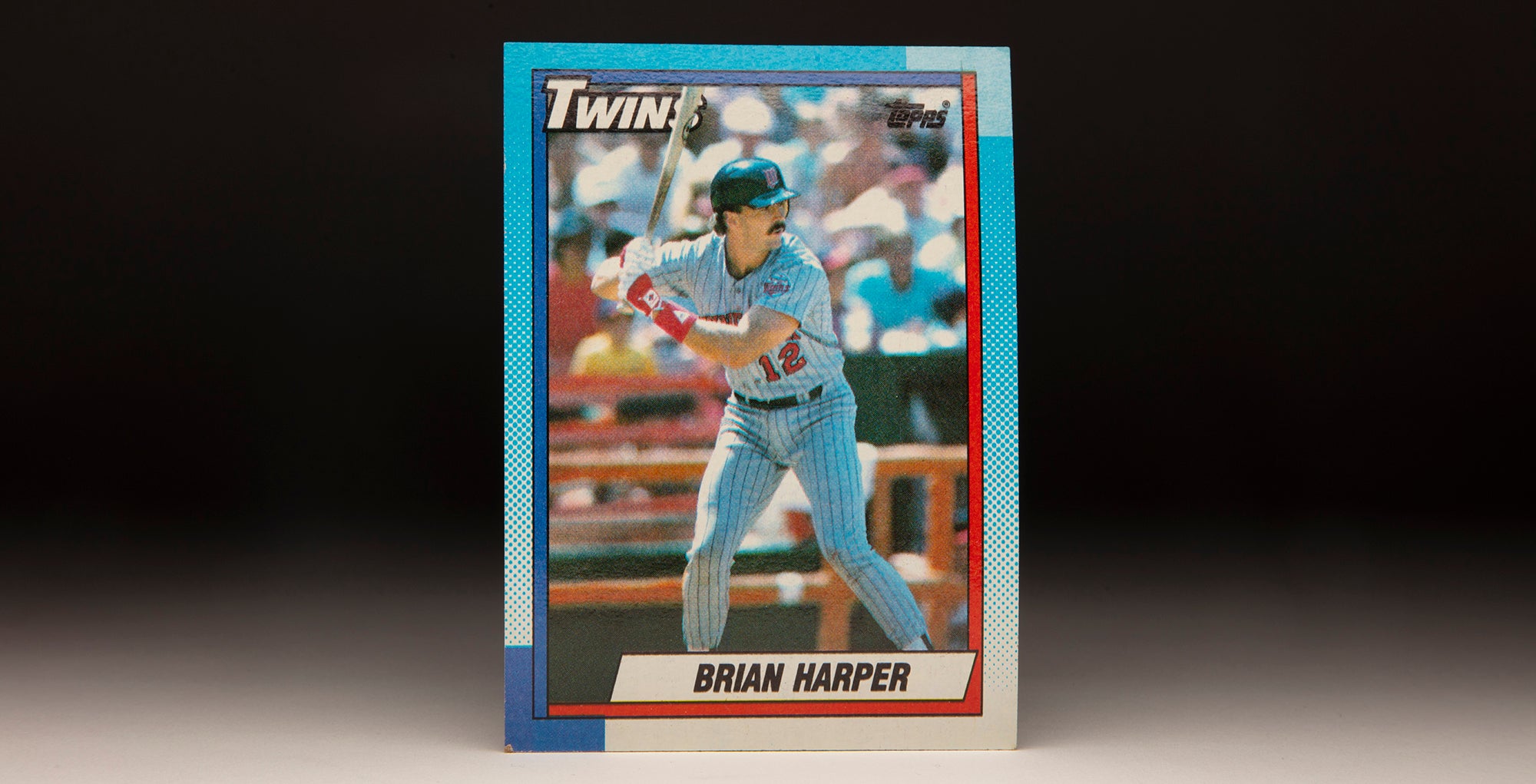

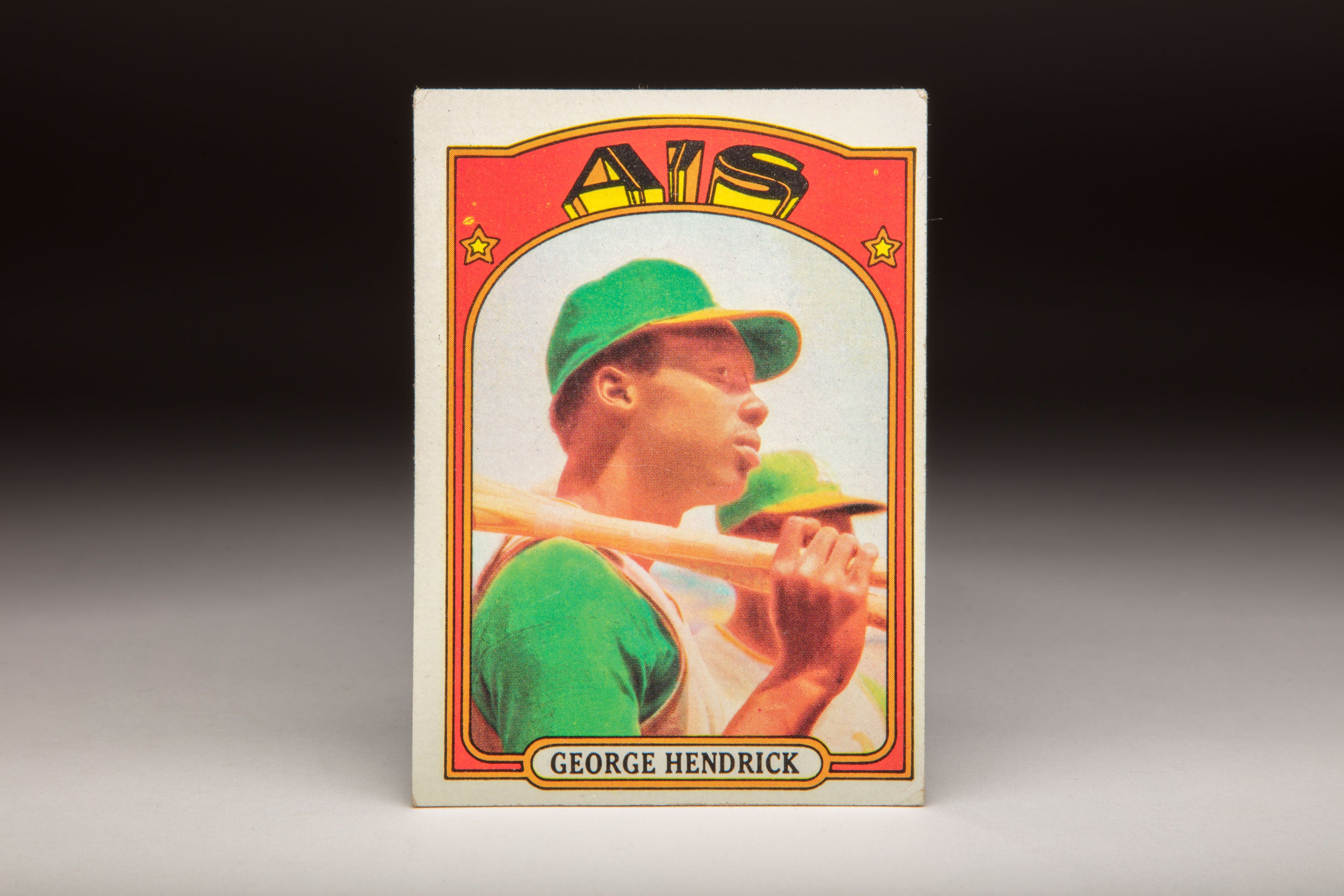

Feeling they could afford to part with pitching, the Pirates traded Tudor and catching prospect Brian Harper to the Cardinals for George Hendrick and minor leaguer Steve Barnard on Dec. 12, 1984. It would be a trade that Pittsburgh would long regret – and one that would put St. Louis back in the World Series.

The trade seemed to be a wash for both teams at first as Hendrick was hitting just .222 with one homer and nine RBI through May while Tudor was 1-7 with a 3.74 ERA in the same stretch. But at that point, Tudor’s former high school baseball teammate Dave Bettencourt called Tudor and told him his delivery was out of synch.

“I said: ‘I know you don’t want to hear this but what you’re doing is you’re not gathering at all,’” Bettencourt told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of his conversation with Tudor. “’Your arm doesn’t catch up with your leg.’

“He’s given me a lot of credit. Sometimes, his quietness leads people to believe he’s cocky. But he’s just quiet and he’s very competitive.”

Tudor’s drive pushed the Cardinals to an unexpected NL East title that year. By the time his amazing 26-game stretch was done, Tudor was 21-8 with a 1.93 ERA and a big league-leading 10 shutouts. He finished second to Gooden in the NL Cy Young Award race and was eighth in the NL MVP voting. Despite Gooden’s dominating numbers, it was Tudor who led the NL in WHIP with a mark of 0.938 compared to Gooden’s 0.965.

“Both Whitey and I felt he would be a good, solid starter who would always keep you in the ballgame,” Cardinals pitching coach Mike Roarke told the Southern Illinoisan in Carbondale, Ill. “(But) if you say anyone will pitch 10 shutouts, I don’t think you can expect that. More than anything, he’s made the great pitches when he’s had to make them.”

Tudor started Game 1 of the NLCS vs. the Dodgers and absorbed the loss in his first postseason action, allowing three earned runs in 5.2 innings in Los Angeles’ 4-1 win. He returned on three days’ rest in Game 4 and allowed just one run over seven innings in the Cardinals’ 12-2 victory. The next day, Ozzie Smith’s dramatic ninth-inning, walk-off homer gave the Cardinals a 3-games-to-2 lead – and St. Louis wrapped up the pennant with a win in Game 6.

Tudor started Game 1 of the World Series against the Royals and allowed just one run over 6.2 innings in the Cardinals’ 3-1 win. He picked up his second win of the series in Game 4, shutting out the Royals on five hits in a 3-0 St. Louis victory that put the Cardinals one win from the title.

“If the series does go seven games,” Herzog told the Chicago Tribune after Tudor’s Game 4 masterpiece, “I want Tudor to pitch that game.”

But what happened over the next three games broke Cardinals fans’ hearts. Kansas City won Game 5 by a score of 6-1 but trailed Game 6 1-0 in the bottom of the ninth inning. Pinch hitter Jorge Orta led off with a ground ball to first, and Jack Clark’s flip toss to pitcher Todd Worrell appeared to beat Orta to the bag. But umpire Don Denkinger called Orta safe, starting a rally that saw the Royals win the game on Dane Iorg’s two-run, pinch-hit single.

The next day, Tudor started Game 7 but labored from the start – allowing a two-run homer to Darryl Motley in the second inning and another in the third before being relieved by Bill Campbell with the bases loaded. Tudor would be charged with three hits, four walks and five runs over 2.1 innings in a game the Cardinals lost 11-0.

In frustration, Tudor punched an electric fan after being removed from the game, opening a wound on his left index finger that required stitches to close.

“It was just a stupid mistake on my part,” Tudor told the Sacramento Bee. “The whole season came down to one game and it was a complete disaster.

“I didn’t pitch well. Call it a choke. Call it what you want.”

At the beginning of Spring Training the following year, Tudor signed a three-year deal with the Cardinals worth a reported $3.4 million. He pitched well in 1986, going 13-7 with a 2.92 ERA. But the wear and tear on his shoulder – he worked 275 innings during the 1985 regular season, plus 30.2 more in the postseason – began to take its toll. He started only two games in September and underwent shoulder surgery following the season.

He won two of his first three starts in 1987 but was the victim of terrible luck on April 19 when he was hit by Mets catcher Barry Lyons while Lyons was diving into the Cardinals dugout at Busch Stadium in pursuit of a popup. Tudor suffered a broken right leg that would sideline him until August.

“Tudor’s going to be all right,” Herzog told the Post-Dispatch. “I think he’ll be back sooner than people think.”

Tudor made his return Aug. 1 and went 8-1 down the stretch, including a 5-0 mark in September as the Cardinals won the division title. He finished the year with a 10-2 record and 3.84 ERA then started Game 2 of the NLCS vs. the Giants, allowing three earned runs over eight innings in the Cardinals’ 5-0 loss.

But Tudor returned in Game 6 with 7.1 shutout innings, outdueling San Francisco’s Dave Dravecky in a 1-0 victory. The Cardinals won Game 7 the next day to advance to the World Series.

Tudor was masterful in his next start, allowing just one run over seven frames in a 3-1 S.t Louis win over Minnesota in Game 3 of the World Series. But in Game 6 – with the Cardinals one win from clinching the title – Tudor was charged with six runs over four innings in the Twins’ 11-5 win. Minnesota won the title with a 4-2 win in Game 7.

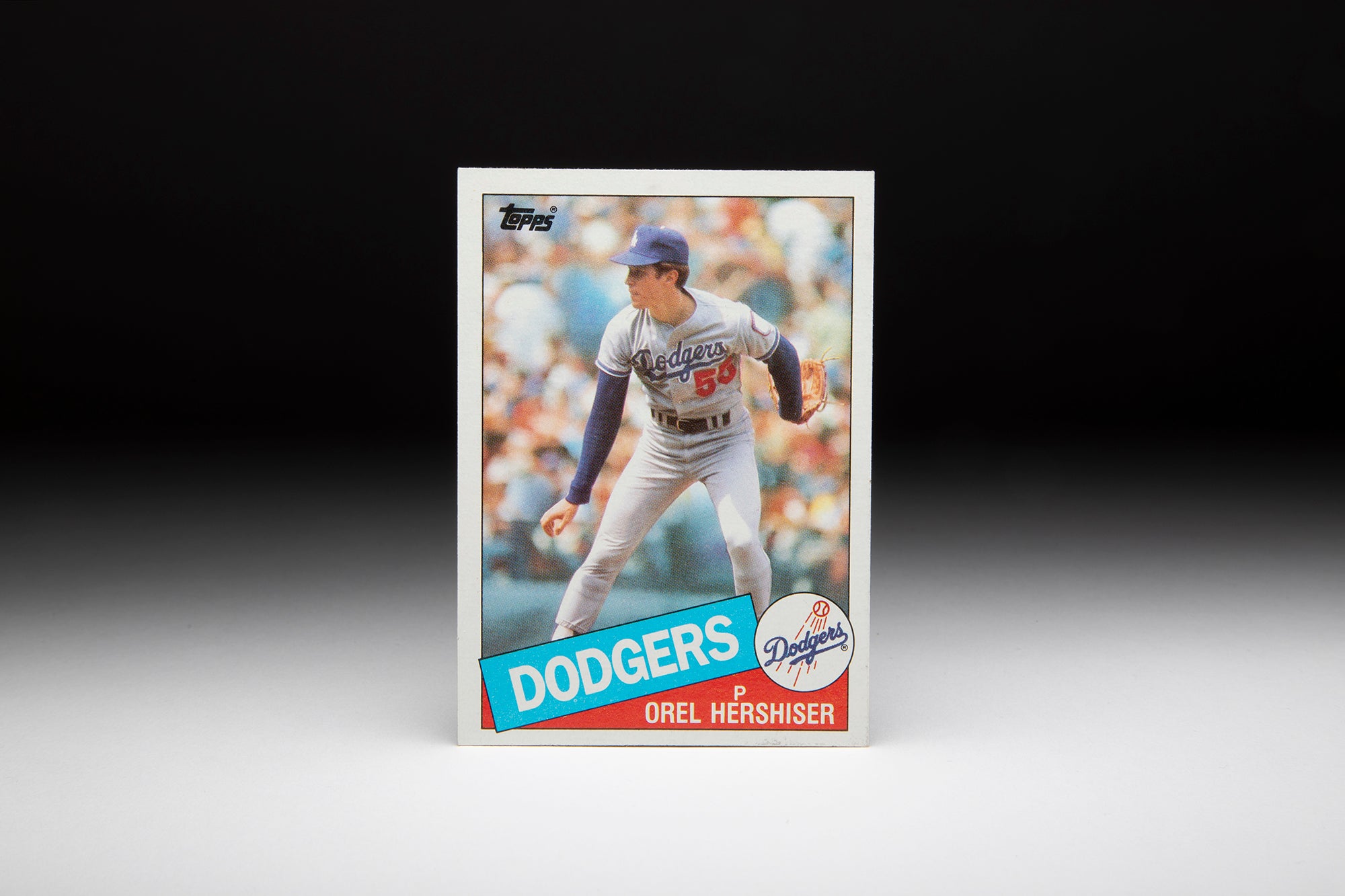

Tudor underwent knee surgery after the season, another result of his collision with Barry Lyons. The injury limited Tudor to one start in April, but he allowed no runs in his first 12 innings of the year and was 6-5 with a 2.29 ERA when the Cardinals traded him to the Dodgers on Aug. 16. Los Angeles, in need to pitching to support Orel Hershiser during a surprise pennant push, sent Pedro Guerrero to St. Louis.

Tudor went 4-3 with a 2.41 ERA in nine starts for the Dodgers as Los Angeles won the NL West. He allowed four runs over five innings in Game 4 of the NLCS vs. the Mets – a game the Dodgers won 5-4 in 12 innings en route to a seven-game victory over New York.

“I have the body of an 80-year-old,” Tudor told Newsday before his start against the Mets. “But I’ll be all right. I can’t guarantee wins or losses, but I can guarantee that I’ll be on the mound.”

In the World Series, Tudor started Game 3 and retired all four batters he faced before he was removed in the second inning. Dodgers team physician Frank Jobe quickly diagnosed Tudor with a sprained ligament in his left elbow, ending his season.

The Dodgers, however, would win the World Series in five games, giving Tudor his first World Series ring.

A week after the World Series ended, Tudor underwent Tommy John surgery. He returned to the Dodgers in June 1989 but made only six appearances and did not post a win or a loss.

With his contract expired, Tudor returned to St. Louis, signing a one-year deal worth $450,000 on Dec. 14.

“I’d take him right away,” Herzog told the Associated Press while campaigning for Tudor to sign with St. Louis. “If he says he can pitch, he can pitch.”

Armed with a fastball that barely broke 80 miles per hour, Tudor pitched and pitched well – allowing no runs in three of his first four starts in 1990. He was 11-3 with a 2.49 ERA on Aug. 10. But that night against Pittsburgh, Tudor faced only six batters – retiring each one but yelling in pain during a pitch to the Pirates’ Barry Bonds. Tudor returned in September but made only one start and three relief appearances, finishing the season with a 12-4 record and 2.40 ERA over 146.1 innings.

Rather than face another shoulder surgery, Tudor announced his retirement soon after the 1990 World Series.

He finished his career with a record of 117-72 and a 3.12 ERA over 1,797 innings and served as a minor league instructor for the Cardinals, Phillies and Rangers during the 1990s. For a 6-foot, 185-pounder who wasn’t even a prospect until he got to college, Tudor had a remarkable big league career.

And for one unforgettable four-month stretch in 1985, John Tudor made pitching look easy.

“I probably want to win more than the next guy,” Tudor told the Post-Dispatch in 1988. “Whatever it takes to win, you do it. I just hate to lose, and I hate to see guys accept losing.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

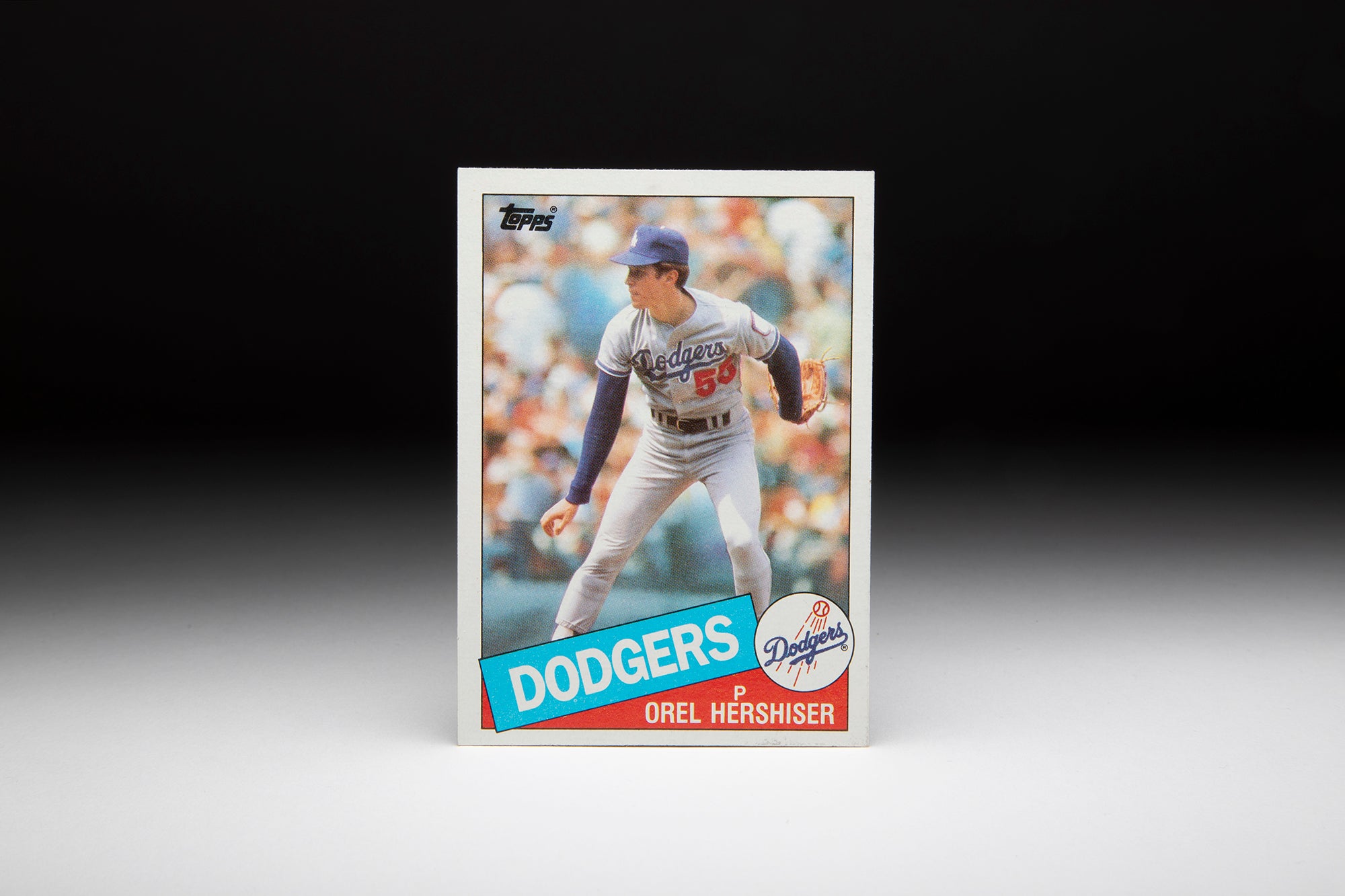

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Orel Hershiser

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

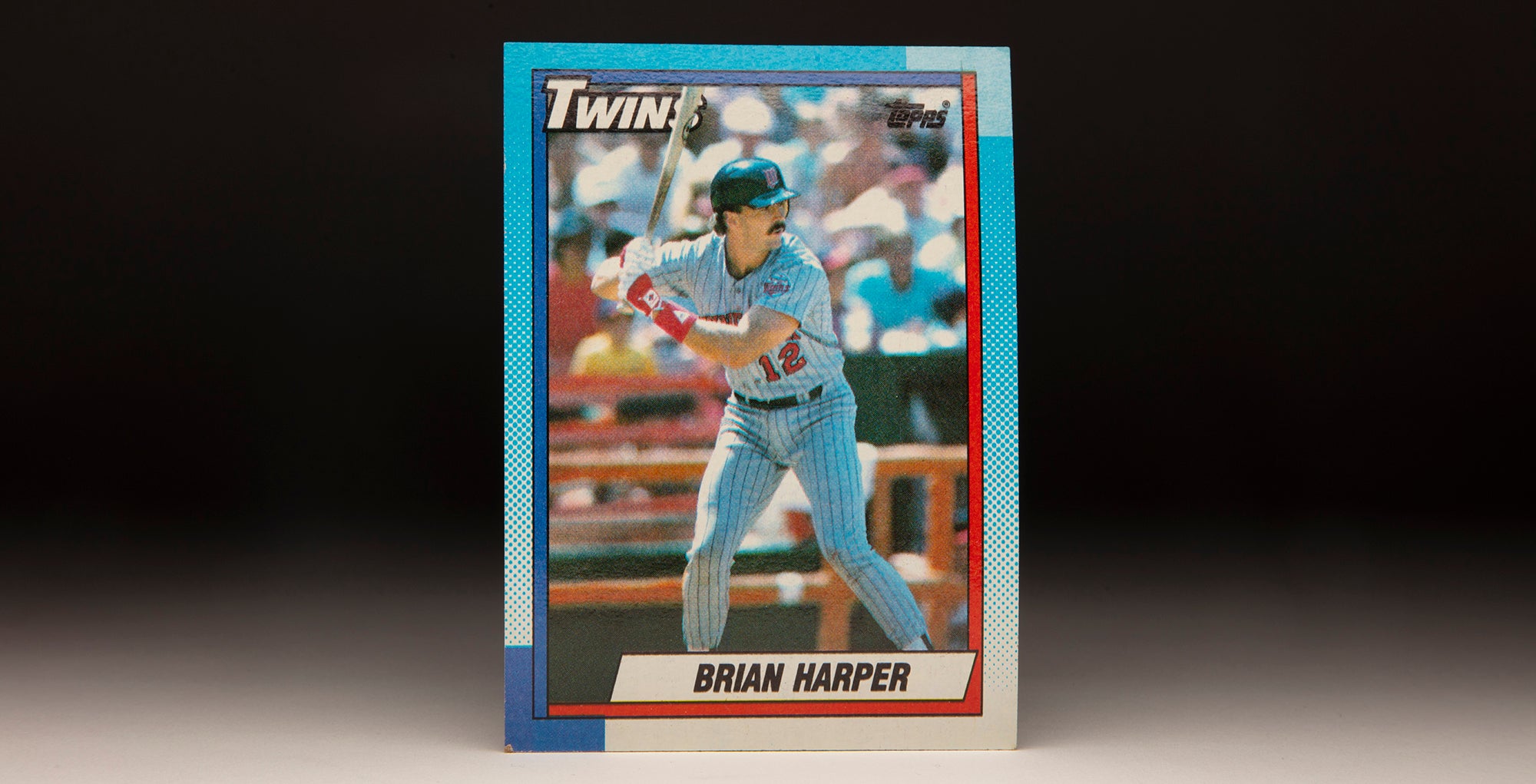

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Brian Harper

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps George Hendrick

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Orel Hershiser

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Brian Harper