Topps called me, and asked did I have pictures of George Hendrick? Of course I did, and sent it in, and received a check for its use. It was my very first sale to Topps. I was delighted.

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps George Hendrick

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps George Hendrick

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

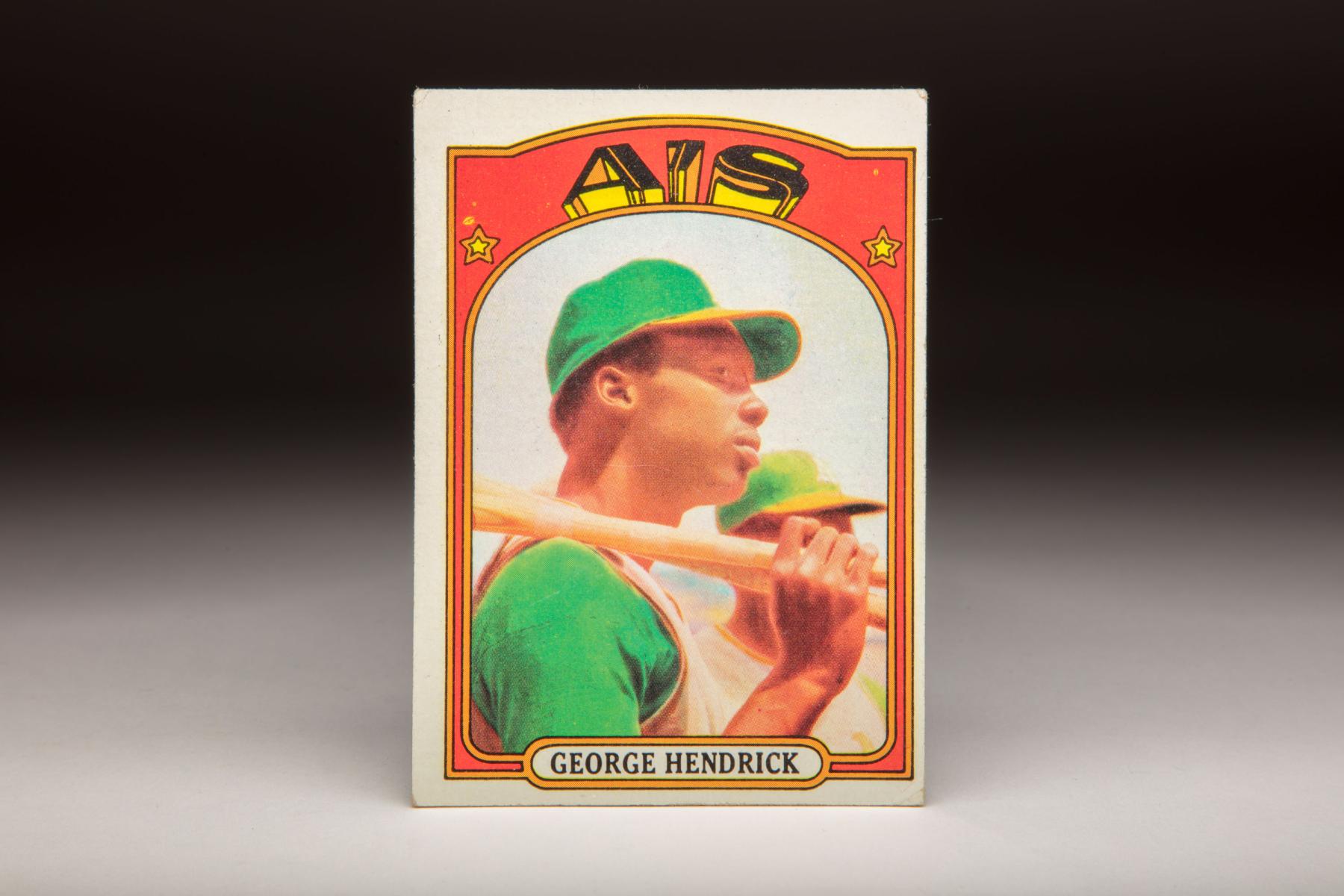

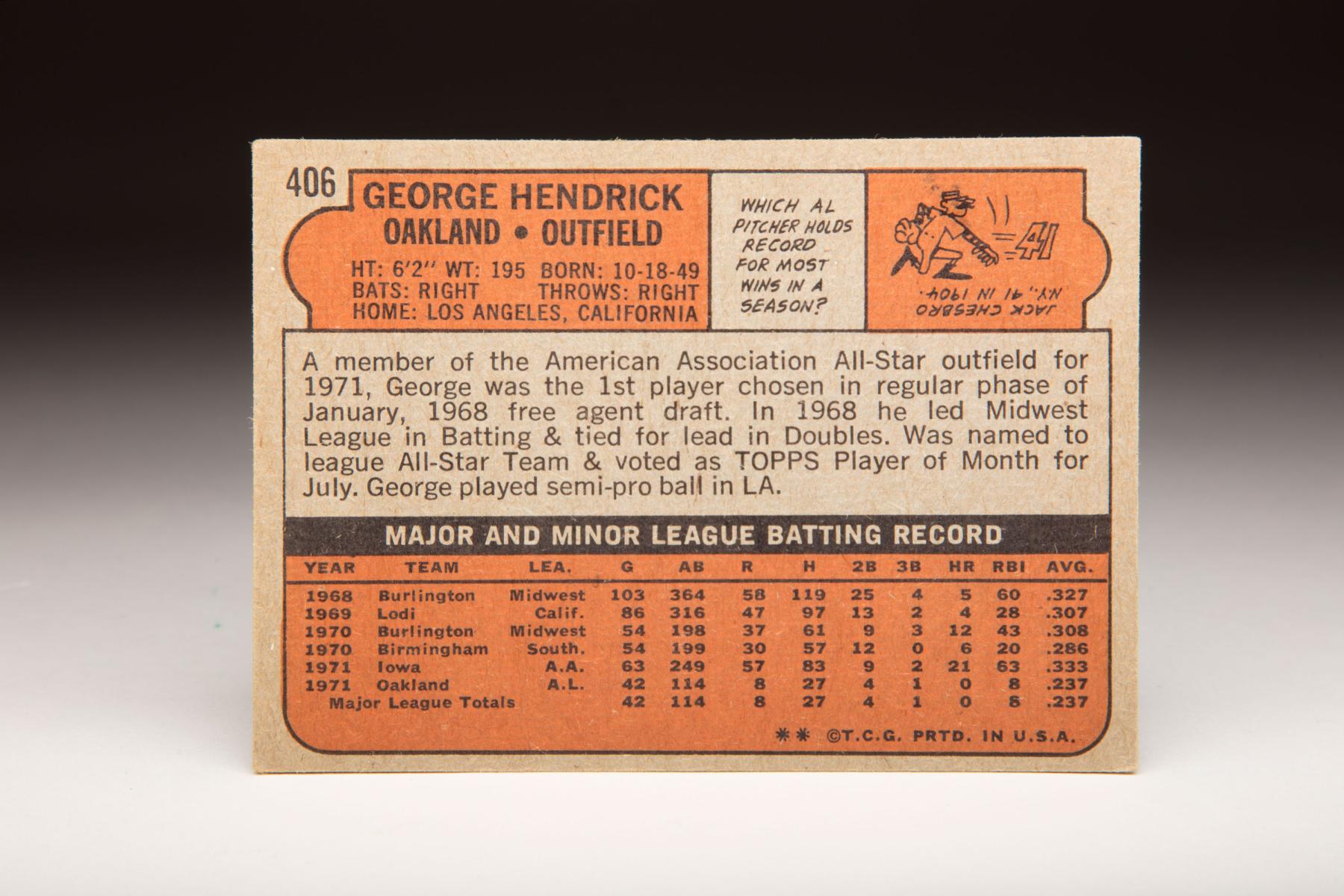

A baseball card takes up little space, two-and-a-half by three-and-a-half inches. It’s the same size that has been in place since Topps standardized cards in 1957.

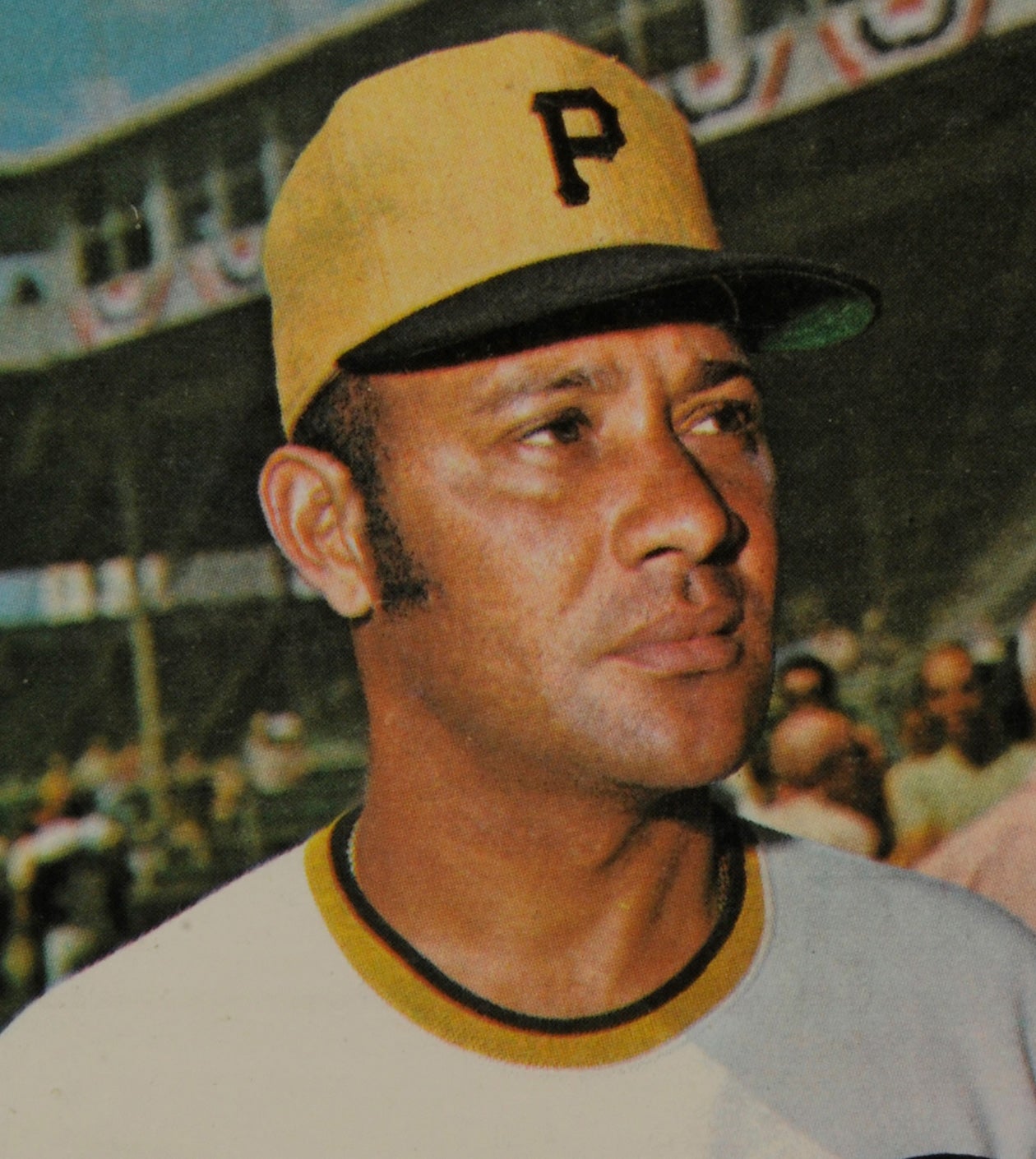

While there is little physical space contained on the surface of a card, the stories behind some cards can sometimes go on for paragraphs (or pages). That is certainly the case with George Hendrick’s rookie card, released 45 years ago as part of Topps’ 1972 set.

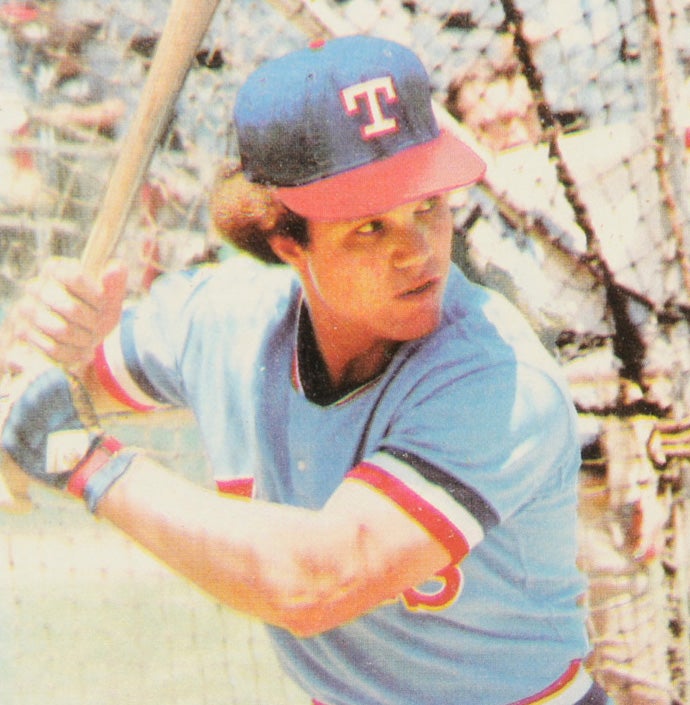

At first glance, the card takes on a surreal look. The green colors of the Oakland A’s’ cap and sleeveless uniforms appear to be nearly glowing. At first, I thought the effect might be created by the bright sunshine of an Arizona afternoon, the setting for this Spring Training shot. (At the time, the A’s trained in Mesa, Ariz.) If a photographer catches the sun at just the right time, at just the proper angle, the effect can be something that appears almost supernatural.

Not satisfied with that explanation, I decided to contact Doug McWilliams, the now retired but once prolific freelance photographer for Topps who has donated over 10,000 of his photo negatives to the Hall of Fame’s collection. I asked Doug if he had taken this photograph of Hendrick at the start of his Topps tenure, which began in 1971. Doug said he had not. So I asked him about the card, and why it looks so bizarre.

“You have asked a question that has puzzled me for 46 years,” said McWilliams, who then proceeded to explain the situation fully. “The very first image I ever sold Topps was at the end of the 1971 season. The regular Topps photographer, from New York, George Heyer, was wary of George Hendrick. Why, I don’t know. George Heyer was a terrific photographer who had a long career with the Saturday Evening Post and Look magazine. George [Heyer] used to spend his summers in Palo Alto, Calif, with his daughter, and shoot in San Francisco and Oakland. I got to know him well.”

McWilliams also knew George Hendrick, a young outfielder who was advancing through Oakland’s farm system. “I had photographed George Hendrick ever since he came up to the A’s from the Iowa Oaks. He was, and is, always very nice to deal with and friendly.

“Topps called me, and asked did I have pictures of George Hendrick? Of course I did, and sent it in, and received a check for its use. It was my very first sale to Topps. I was delighted.”

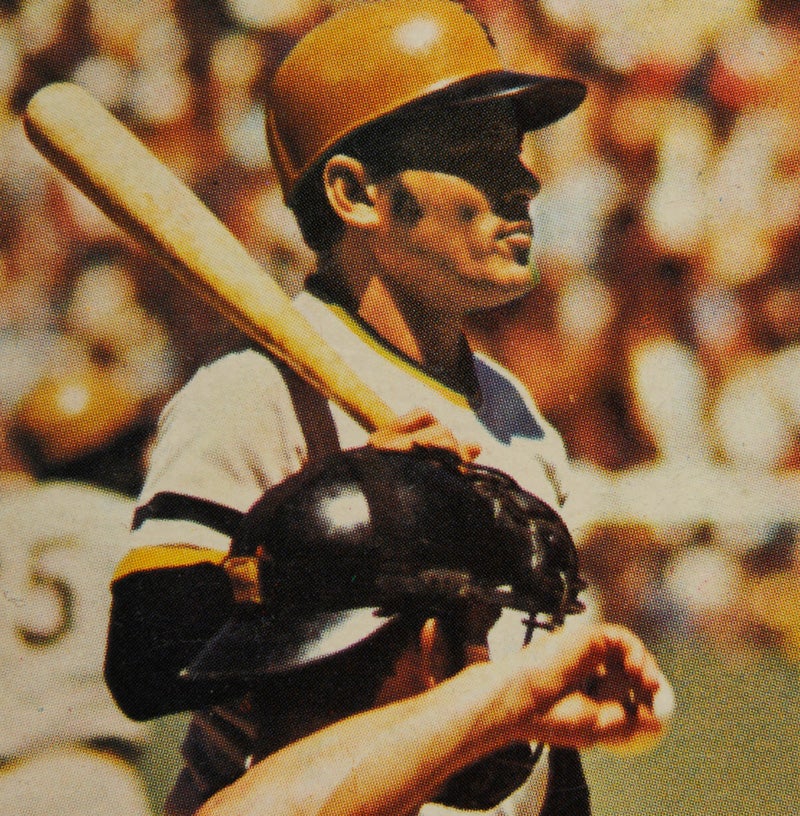

McWilliams felt so proud of his Hendrick shot that it became the impetus for a special creation. “Later on, I made a faux 1972 card of George, using the image that I shot of George. George liked the image so much at the time, that I made color postcards for him to send out to his fans.”

Fully expecting to see the photo used in the new set of Topps cards, McWilliams soon received a jolt. “When the card came out in 1972, I was shocked and surprised.” For some reason, Topps chose not to use the McWilliams shot, but instead relied on the Arizona photograph of unknown origin.

“They had taken a black-and-white shot and colorized it,” McWilliams recalls. “You have to realize that this was way before computers and ‘Photoshop.’ I would guess that it was done with ‘photo’ transparent water colors, which was the way people made color prints easily, compared to the dye transfer process, which was also in use at the time.”

The colorization technique explains why Hendrick’s 1972 card looks so surreal, as if it were photographed in The Twilight Zone. To this day, McWilliams has no idea where Topps came up with the photograph. “I [still] don’t know where the black-and-white image came from. It’s not one I’ve seen in the ‘A’s files’ of photos over all these years.”

Perhaps no one knows. What we do have is a memorable rookie card for a player who went on to enjoy a long major league career that lasted 18 seasons. As it turned out, his career would be delayed at the start of the 1972 season. Hendrick failed to make Oakland’s Opening Day roster, instead sent back to Triple-A Iowa for additional apprentice work in the minor leagues.

The move surprised some in Oakland, given Hendrick’s high ranking as a prospect. Scouts loved Hendrick’s bat speed, particularly his quick hands. As Hendrick swung, he snapped his wrists, in a way that reminded some talent evaluators of Ernie Banks in Chicago. The comparison to Banks placed Hendrick in special company.

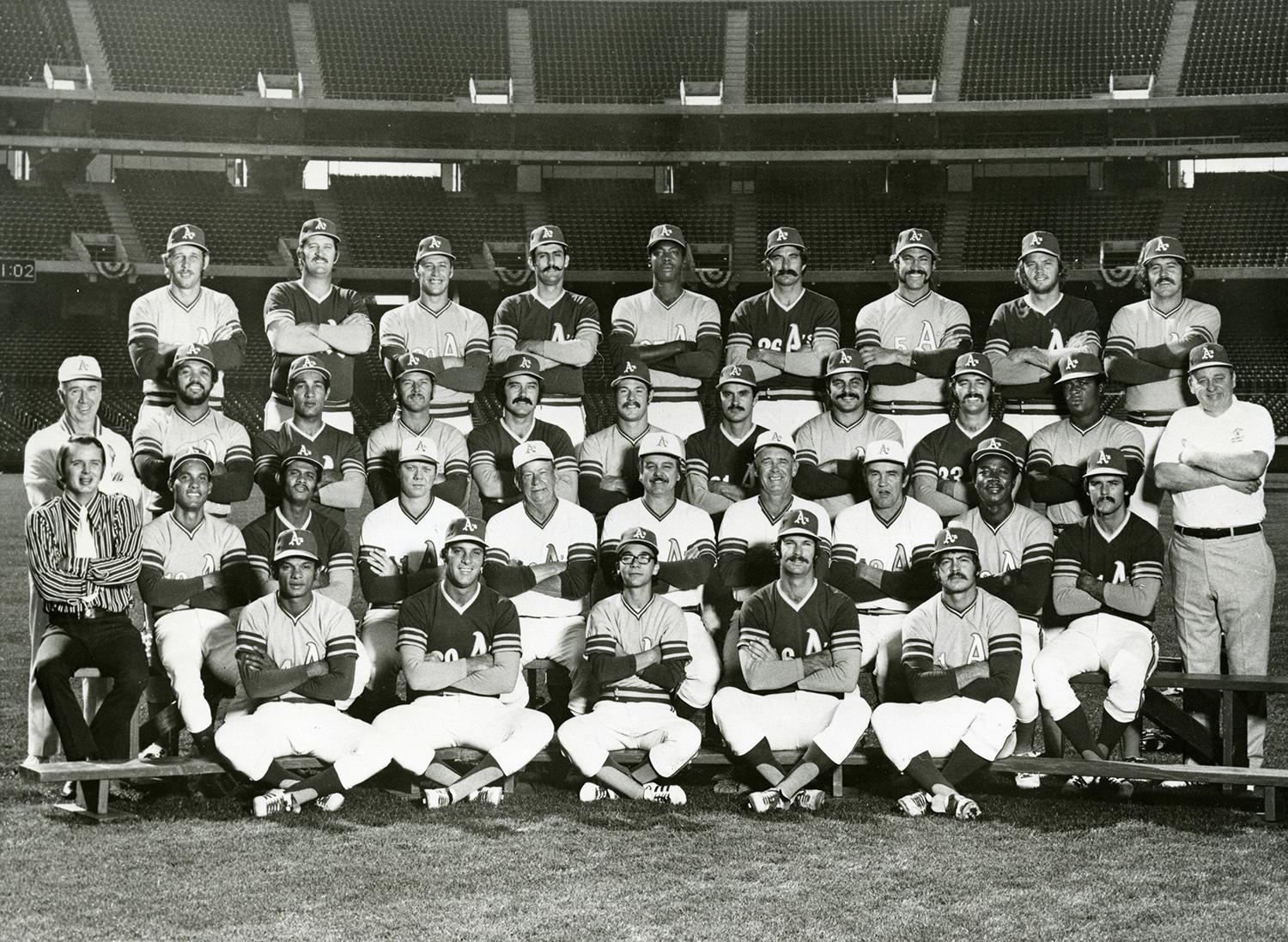

Later that summer, the A’s recalled Hendrick, in time to make him eligible for the postseason. Fast forward to Game 5 of the American League Championship Series. When Reggie Jackson tore his hamstring in that decisive matchup, manager Dick Williams summoned Hendrick as his replacement in center field. In the fourth inning, Hendrick reached base on an error and then came racing home on a Gene Tenace single. Detroit Tigers catcher Bill Freehan tried to apply the tag, but he bobbled the ball, allowing Hendrick to score what turned out to be the pennant-winning run. With that, Hendrick and the A’s moved on to the World Series, where they upset the Cincinnati Reds.

The following spring, Hendrick reported to training camp in Arizona, believing that he would have a chance to compete for the center field job. A’s owner Charlie Finley told Hendrick that would not be the case; instead, Hendrick would report to Triple-A for a second consecutive season. In response to Finley’s message, Hendrick asked to be traded. On March 24, Finley obliged, sending Hendrick and catcher Dave Duncan to the Cleveland Indians for former All-Star catcher Ray Fosse and utility infielder Jack Heidemann.

Unlike the A’s, whose outfield was stocked with Jackson, Joe Rudi, and Billy North, the Indians had openings in their outfield. They made Hendrick their starting center fielder and watched him hit 24 home runs while slugging a respectable .452.

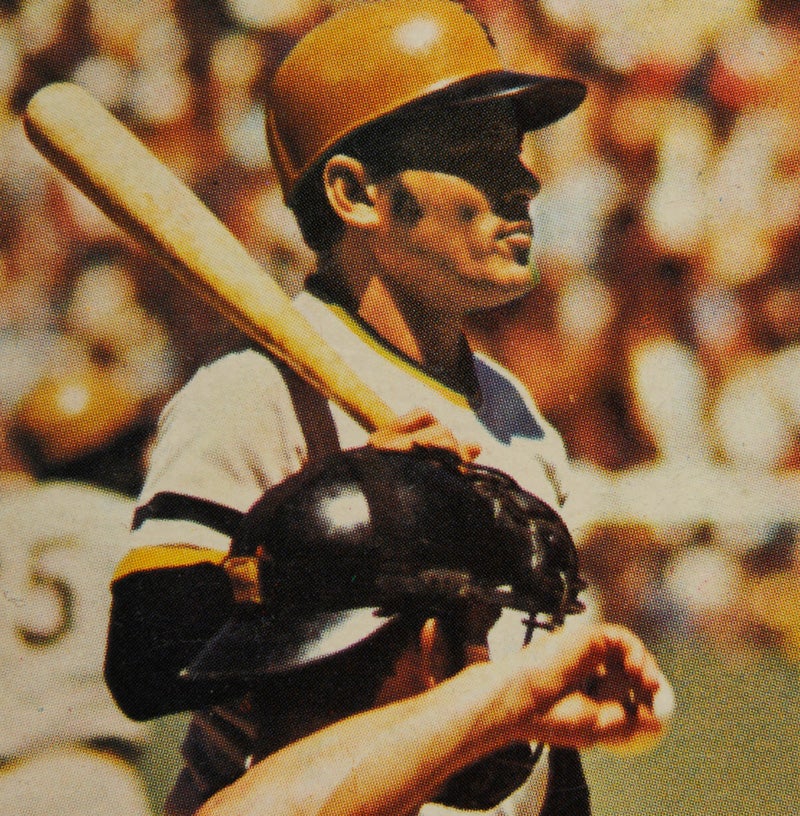

The following spring, McWilliams had a chance to again make acquaintances with Hendrick. “I took my Dad with me to Tucson to shoot the Cleveland Indians for Topps,” says McWilliams, recalling that day from over 40 years ago. “While I was taking George’s pictures, he asked me: ‘Is that your Dad, over there?’ I said yes, finished with him, and continued to photograph other Indians players.

“When I had a slow spot in shooting, I looked around for my Dad. I couldn’t find him anywhere, and began to worry. Then I looked up in the stands, and there was my Dad sitting with George Hendrick having a long conversation. It was wonderful to see, as my father had no interest in sports or baseball.

“On the way home, he was all enthusiastic, and said to me for the first time: ‘You have a very interesting job with these fellows.’ He had never said anything to me up till then about me being a professional photographer. I had been one for 13 years or so. It made my day, and I will be forever thankful for George H., taking the time to speak with my Dad and treating him so nicely.”

While Hendrick made friends with his personality, he also won over the Indians with his hitting, putting up good numbers in 1974 and ’75, and making the All-Star team each season. In contrast, he struggled with his fielding. His defensive play in center field left something to be desired, so the Indians shifted him, at first to right field and then to left field.

All in all, Hendrick became a highly productive player for the Indians, but his style of play irritated Cleveland management. In a 1974 game, he failed to run hard on two ground balls, prompting manager Ken Aspromonte to bench him for the next 10 days. In 1975, his new manager, future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, expressed regard for Hendrick on a personal level but also became irritated with him over his lack of hustle. Hendrick also heard boos from fans at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium.

After the 1976 season, the Indians ran out of patience and peddled Hendrick to the San Diego Padres for outfielder Johnny Grubb and two others. Hendrick put up big numbers for the Padres in 1977, hitting .311 with a .381 on-base percentage. It was his best season, but to the surprise of many, Hendrick found himself moving on again that winter; this time, the Padres traded him to the St. Louis Cardinals for right-hander Eric Rasmussen.

The move to St. Louis turned out to be the break that Hendrick needed. His game, which featured a line-drive approach to hitting more than a reliance on pure power, fit St. Louis’ Busch Memorial Stadium perfectly. He hit .300 or better three times for the Cardinals, while reaching the 100-RBI mark twice. He also received votes in the MVP balloting on four occasions. In 1982, he became an important part of the Cardinals’ world championship effort, as St. Louis defeated Milwaukee in a hard-fought World Series. For his efforts, Hendrick earned his second world championship ring.

Hendrick also connected with his manager, Whitey Herzog, who persuaded him to hustle more consistently. One day, Herzog reprimanded Hendrick for not running hard. This time, the message was heard. The veteran outfielder started to run out grounders and fly balls with more passion than he had shown in the past.

Whitey Herzog, manager of the St. Louis Cardinals from 1980-1990, led the Redbirds to three NL pennants and one World Series title. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

Hendrick also showed himself to be a team player. When the Cardinals made the controversial trade that sent Keith Hernandez to the New York Mets, Herzog asked Hendrick to switch positions and replace their longtime first baseman. Hendrick made the move willingly; in fact, he had earlier approached Herzog about the possibility of taking grounders at first base because of his fear that one day he would no longer be able to play the outfield. Moving to first base without a complaint, Hendrick reinforced a reputation as a popular member of the Cardinals’ clubhouse.

Although Hendrick played the best ball of his career for the Cardinals, he remained somewhat of an overlooked player. That was partly his own doing; a private man, Hendrick did not grant interviews to members of the media. That’s why some writers nicknamed him “Silent George.” Other critics referred to him as “Jogging George” or “Captain Easy,” names that referenced his earlier reputation as a player who did not always hustle.

Hendrick also became known for doing things his way. In contrast to other players from the 1980s, he stretched his pant legs all the way down to his ankles, so that they would cover his stockings. In today’s game, the majority of players do this, but as I recall, Hendrick was the very first, making him a pioneer in the arena of baseball fashion.

After the 1984 season, the Cardinals traded Hendrick, not because of any dissatisfaction with him, but because they needed pitching. Dealt to the Pittsburgh Pirates for lefty John Tudor and catcher/outfielder Brian Harper, Hendrick had a forgettable tenure in Pittsburgh, where the Bucs were headed to a 104-loss season in 1985. In need of a complete rebuild, the Pirates sent the aging outfielder and two veteran left-handers, John Candelaria and Al Holland, to the California Angels for three younger players. Hendrick played well in 1986, but struggled the next two seasons. In the winter of 1988, he became a free agent, but ended up retiring and eventually turned to a career in coaching. He now works in the front office of the Tampa Bay Rays, where he serves as a special advisor to baseball operations.

A few years ago, I learned a little bit more about Hendrick from one of my co-workers at the Hall of Fame, Pat Kelly, who used to head up the Library’s Photo Department. Pat had met Hendrick while he was playing minor league ball for the Burlington Bees in the late 1960s. They talked for two full hours at the ballpark, engaging in a pleasant and wide-ranging conversation. Later on, Hendrick sent Pat an autographed baseball.

Just as Doug McWilliams once learned, the real life George Hendrick was far different than his reputation within the game. In a similar way, Hendrick’s rookie card gave us a distorted view of what he actually looked like, a mystery that is now solved thanks to the insight of the legendary Doug McWilliams.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan