- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Don Buford

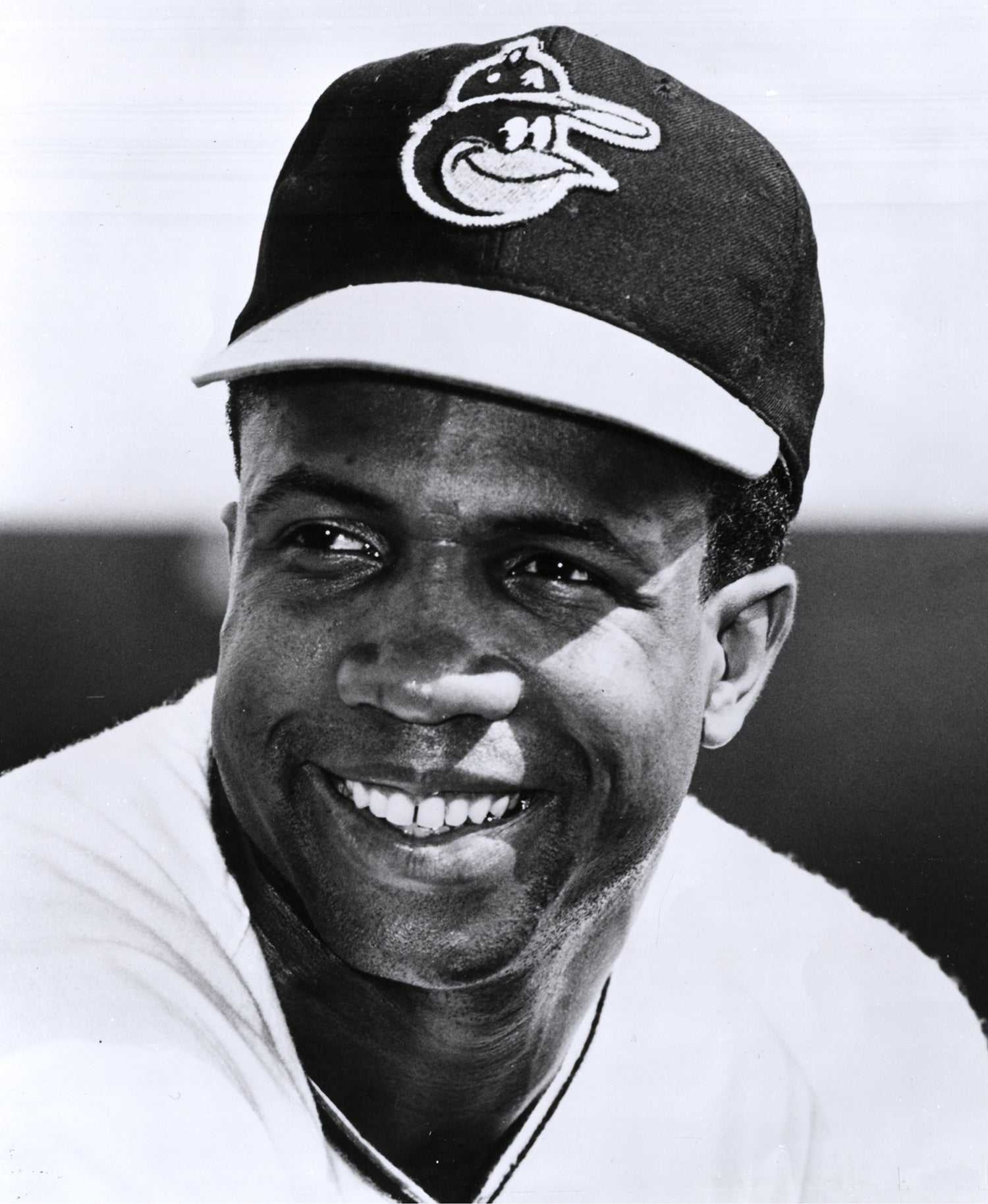

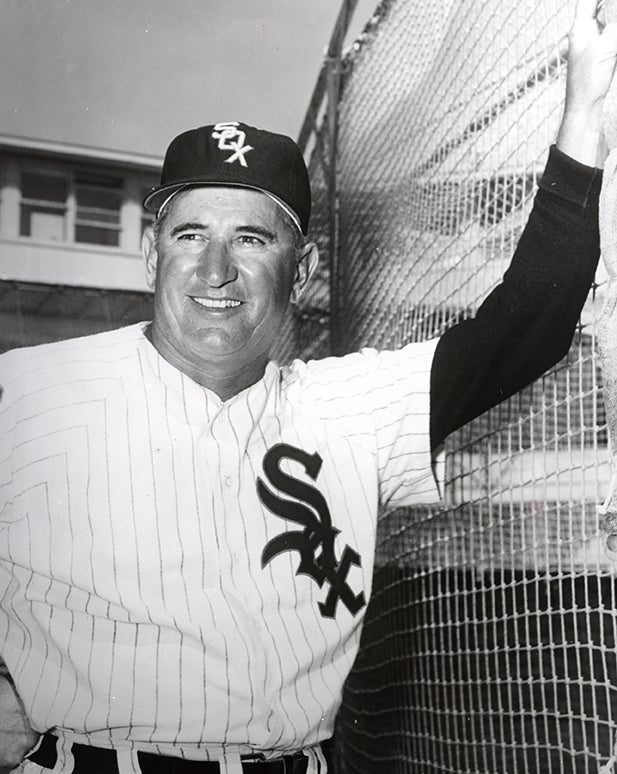

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Don Buford

Don Buford’s big league career was delayed at the start due to his success on the gridiron. And a salary dispute cost him at least a couple years in the majors in his 30s.

What was left, however, was a 10-year stretch that featured three American League pennants and a World Series title as one of the best leadoff hitters in the game.

Born Feb. 2, 1937, in Linden, Texas, Buford lost his father – who played semi-pro baseball – in a shooting accident when he was in grade school. His mother moved the family to Southern California soon after, and Buford excelled as an all-around athlete despite a frame that would only reach 5-foot-7 after he became a professional.

At Dorsey High School – which also produced big leaguers like Derrel Thomas and Chili Davis as well as Hall of Famer Sparky Anderson – Buford starred in football and baseball (and also lettered in track and basketball) while leading his team to the Los Angeles city baseball title as a senior in 1954. Buford enrolled at Los Angeles City College – earning the starting quarterback job for LACC – before transferring to the University of Southern California, where he played both baseball and football.

“I hope to make baseball my career when I graduate from college,” Buford told the California Eagle.

By 1957, Buford was excelling on both sides of the football for USC, playing halfback and defensive back while also returning kicks. In the spring of 1958, Buford played on the Trojans baseball team that won the College World Series on the strength of the hitting of future big leaguer Ron Fairly. Then in the fall of 1958, Buford led USC with 306 yards rushing while also starring on defense for a Trojans team that went 4-5-1.

“(He’s) more effective when he doesn’t get too much work,” USC coach Don Clark told the Independent Star News of Pasadena, Calif. “He’s so small that he takes quite a beating.”

Listed then at 5-foot-5 and 154 pounds, Buford knew his best bet for a pro career was on the diamond. So in 1959, Buford signed with the White Sox – who started him out with Triple-A San Diego in 1960. Buford soon was moved to Class B Lincoln of the Three-I League, where he parlayed his skill as a switch-hitter to a .289 batting average with a .416 on-base percentage (thanks to 91 walks) and 36 steals in 120 games.

“I began switch-hitting as a kid,” Buford told the Baltimore Sun. “I kept it up because I like the idea of the ball always coming toward me, especially those left-handers’ curves.”

Promoted to Class A Charleston in 1961, Buford hit just .236 but drew 78 walks while showing his advanced batting eye from both sides of the plate. He returned to the South Atlantic League in 1962, this time with Savannah/Lynchburg, hitting .323 with 91 walks in 111 games.

The White Sox brought Buford to their big league Spring Training camp in 1963 and moved him from outfield to third base. He won a spot with Triple-A Indianapolis and hit .336 in 152 games, leading the International League in batting average, runs (114), hits (206), doubles (41) and stolen bases (42) while being named the league’s Most Valuable Player.

On Sept. 14, 1963, Buford made his big league debut – doubling and scoring a run in Chicago’s 7-5 win over Washington. He would hit .286 in 12 games down the stretch for a White Sox team that won 94 games and finished second in the American League.

On Dec. 10, the White Sox traded longtime second baseman – and future Hall of Famer – Nellie Fox to Houston, opening the door for Buford at second base.

“When we traded Nellie Fox to Houston, Don Buford (became) our second baseman,” White Sox manager Al López told the Indianapolis Star.

Buford had no problem with the transition – and was the talk of White Sox camp in the spring of 1964.

“I’ve become accustomed to second base now and I like it just as well as third,” Buford told the Indianapolis Star.

Buford hit .262 in 135 games as a rookie, scoring 62 runs while helping Chicago win 98 games – good for another second-place finish behind the Yankees. The White Sox finished in second again in 1965 – this time behind the Twins – as Buford hit .283 with 93 runs scored and 17 steals while earning votes in the AL MVP balloting.

The White Sox’s string of three straight second-place finishes came to an end in 1966, but new manager Eddie Stanky turned his charges loose on the base paths – and Buford stole a team-high 51 bags, finishing just one behind league leader Bert Campaneris. Buford led the league with 17 sacrifice bunts while appearing in a big league-high 163 games – 133 of which came at third base as Stanky decided on a position switch for Buford – and hitting .244.

Buford also led all AL third basemen in errors with 26. He split time between third and second in 1967, hitting .241 with 34 steals – again finishing second in the AL behind Campaneris – as the White Sox battled with the Tigers, Twins and Red Sox in one of the most thrilling pennant races in history. Buford’s batting average tied for the team lead on a Chicago team that hit just .225 but stayed in the pennant chase until the season’s final week thanks to a 2.45 team ERA.

On Nov. 29, the White Sox – looking for more hitting – traded Buford along with pitchers Bruce Howard and Roger Nelson to the Orioles in exchange for Luis Aparicio, John Matias and Russ Snyder. The Orioles made the move with the intention of opening the shortstop job for Mark Belanger, but with Brooks Robinson and Davey Johnson set at third and second, respectively, Buford seemed to be simply a throw-in in the deal.

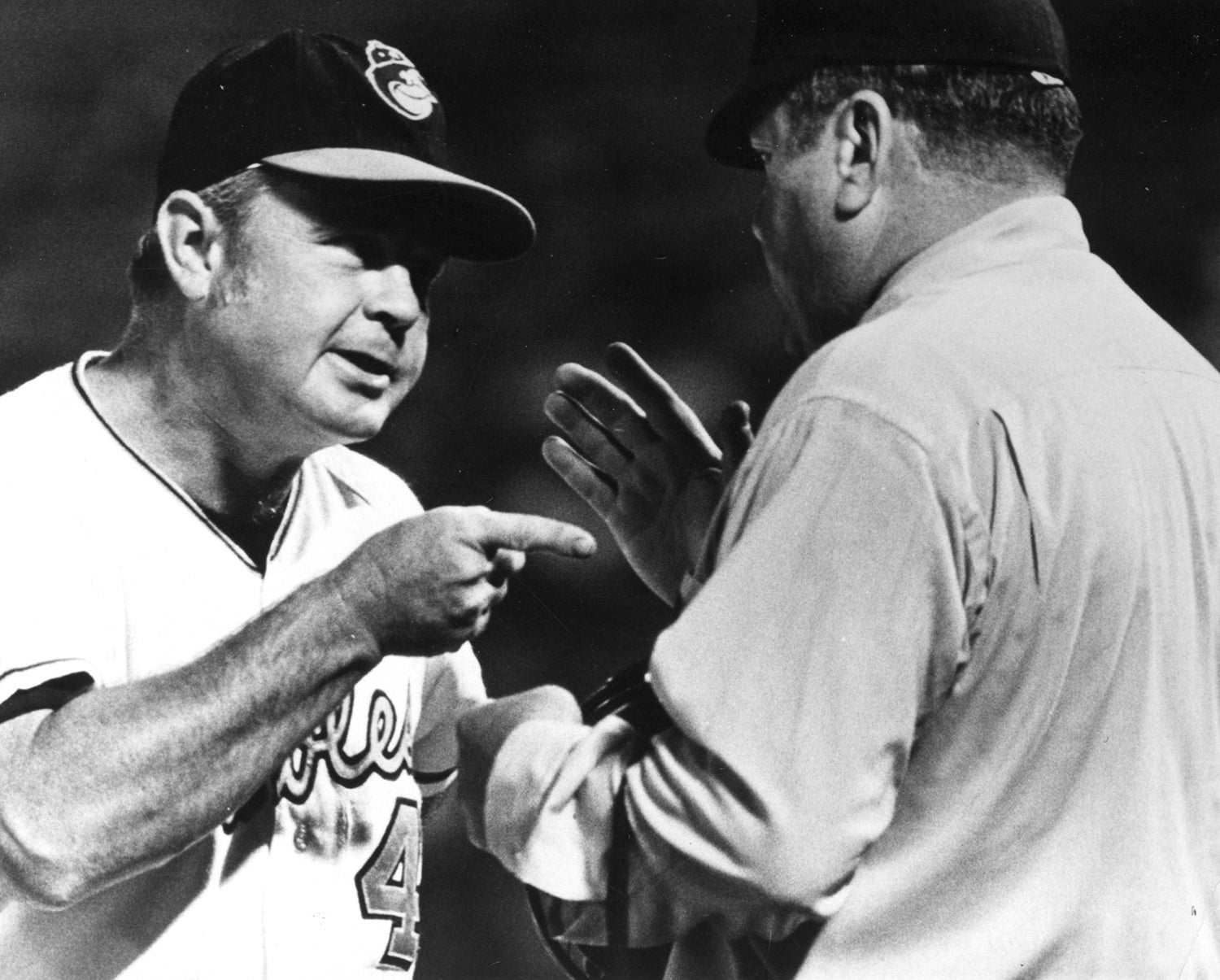

But when Earl Weaver replaced Hank Bauer as Orioles manager in July of 1968, Buford went from a bench player to starting outfielder as Weaver, who remembered Buford from their time in the minor leagues, was enamored with Buford’s ability to get on base. Buford finished the 1968 season hitting .282 with 27 stolen bases and a .367 on-base percentage in 130 games – having hit .298 with 51 runs scored in 82 games after Weaver took over.

“Buford was outstanding – great – especially over the second half of the season,” Weaver told the Baltimore Sun in Spring Training of 1969 while naming Buford the team’s starting left fielder and his leadoff hitter. “Any club would be lucky to have him as its leadoff man, the way he got on base and the way he can steal to keep you out of the double play in the first inning.”

Buford drew three walks against the Red Sox on Opening Day, the posted back-to-back four RBI games against Boston a week later. He was hitting .292 at the All-Star break and finished the year with a .291 batting average, 99 runs scored, 31 doubles, 11 homers, 64 RBI and 96 walks.

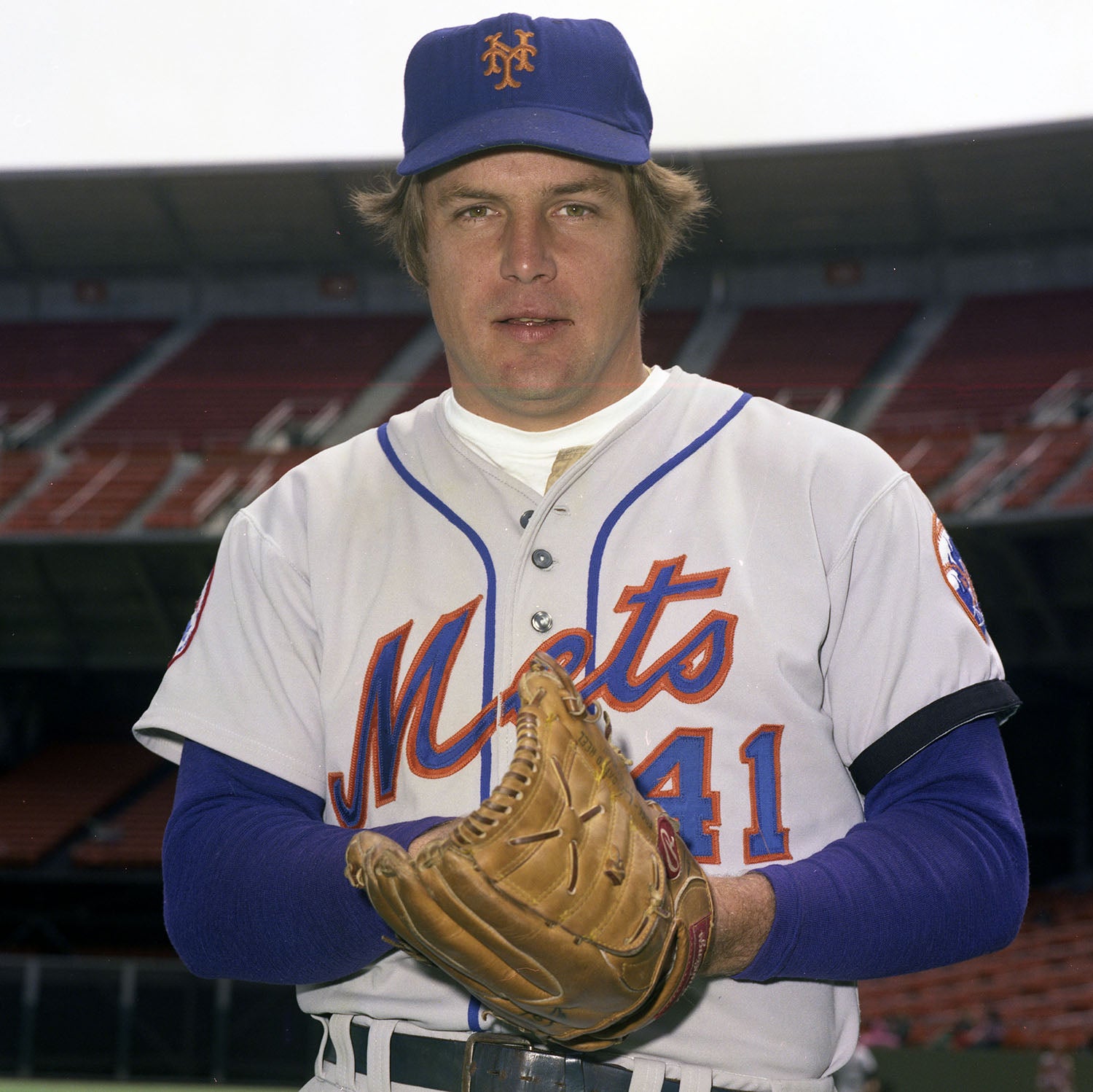

The Orioles won 109 games that season, and Buford hit .286 in his first postseason action as Baltimore swept Minnesota in the first American League Championship Series. Then in the World Series, Buford led off the bottom of the first inning of Game 1 with a home run off Tom Seaver and later doubled home Belanger, powering Baltimore to a 4-1 win.

They would be the only hits Buford recorded in the series as the Mets defeated the Orioles in five games. But the Orioles were far from a one-year wonder.

In 1970, Buford hit .272 with a .406 on-base percentage, drawing 109 walks while hitting 17 homers, scoring 99 runs and driving in 66 runs. The Orioles won 108 games and another AL East title, once again sweeping the Twins in the ALCS as Buford hit .429 with a homer and three RBI. He started in left field in the first four games of the World Series against Cincinnati, totaling three walks and three runs scored.

Weaver used Merv Rettenmund in left field in the deciding fifth game as Baltimore won its second World Series title in five seasons. Buford did not care, celebrating the victory in the winning clubhouse with enthusiasm usually reserved for Little League champions.

Buford entered the 1971 season at 34 years old, and Weaver adeptly kept all his outfielders fresh by using a “four-to-make-three” platoon of Buford, Rettenmund, Frank Robinson and Paul Blair. Buford played in 122 games and hit .290 with 89 walks, 19 homers, 54 RBI and an AL-best 99 runs scored. He was selected to his first All-Star Game that summer and received votes in the AL MVP balloting for the third time in five seasons.

Buford had four hits in seven at-bats as the Orioles swept the Athletics in the ALCS. He hit .261 in the World Series with home runs in Game 3 and Game 6, the latter cutting the Orioles’ deficit to 2-1 in the sixth inning in a game Baltimore rallied to win in 10 innings. But Pittsburgh won Game 7 – and though no one knew it yet, the Orioles’ string of dominance was at an end.

Buford’s Orioles’ career was nearly over as well. He entered Spring Training of 1972 feeling fit, but at 35 – and with top prospect Don Baylor nearly ready for the big leagues – Buford was the subject of speculation by fans and the media.

“I think I can play every game,” Buford told the Miami Herald. “But what player doesn’t?”

Buford was hitting .322 through May 10 but entered a prolonged slump that saw his average dip below .200 in mid-June. By the end of the season, the Orioles had dropped to third place in the AL East and Buford was hitting .206 with just five homers, 22 RBI and 46 runs scored in 125 games.

When Buford and the Orioles could not agree on a contract for 1973, the team sold his contract to the Taiheiyo Club Lions of the Japanese Pacific League – with the deal coming on Buford’s 36th birthday.

The two-year deal was reportedly worth $85,000 per season.

“At best, I would be a utility player next season,” Buford told the Sun about the Orioles’ youth movement after agreeing to his deal in Japan. “I hate sitting on the bench. It was tough to leave, and it was really a difficult decision to make. You have got to make it sooner or later, though. Players move on continually.”

Orioles management acknowledged the decision was tough for them as well.

“I am happy for him but sorry for the Orioles to lose a guy and a family of particularly high quality,” Baltimore general manager Frank Cashen told the Sun. “The Orioles will always have the utmost respect for Don Buford.”

Buford played for four seasons in Japan – three with Taiheiyo from 1973-75 where he averaged .279 with 18 homers, 68 runs scored and 65 walks per season. He played his final season with the Nankai Hawks in 1976 before returning stateside, where he worked as a personnel manager for the department store chain Sears, Roebuck & Co. before being hired as a Giants coach in 1981 by former teammate Frank Robinson.

Buford later served on Robinson’s staff with the Orioles and Nationals and coached his son Damon, who had a nine-year big league career with the Orioles, Mets, Rangers, Red Sox and Cubs – at the University of Southern California.

“We both play outfield, and we both have good speed and we both are quiet,” Damon Buford told the Sun about his father when he was a rookie with the Orioles. “But I’m taller than him.”

Don Buford totaled 1,203 hits, 200 stolen bases, 672 walks and 718 runs scored over a 10-year career that included three American League pennants and the 1970 World Series title.

In his nine full big league seasons, Buford played on teams that finished either first or second six times.

“I feel I’ve always been a competitor,” Buford told the Sun. “And I don’t figure anybody will take (my) job away because I’ve been lackadaisical or didn’t hustle.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

In 1968, Weaver began The Oriole Way in Baltimore

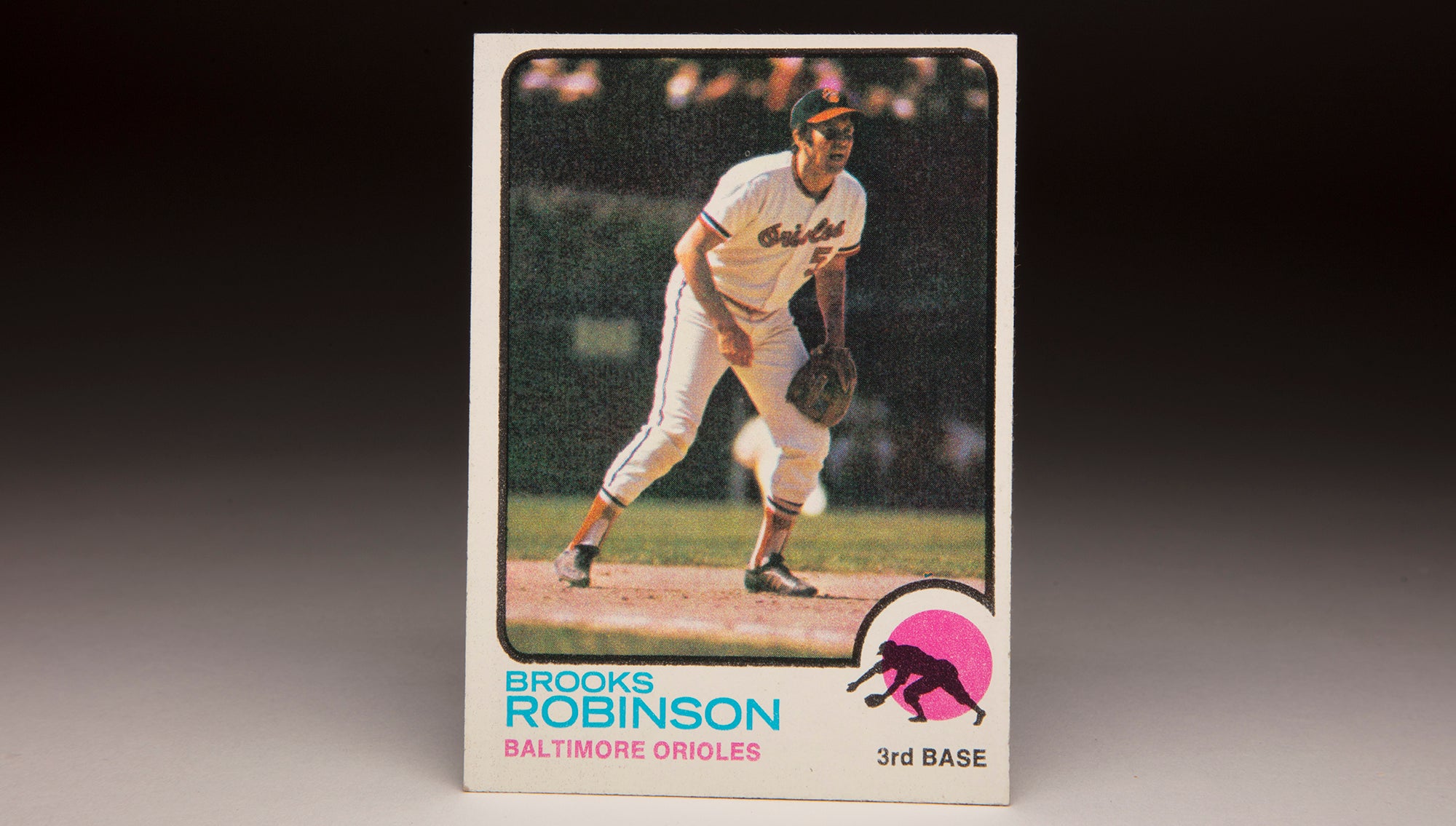

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Brooks Robinson

Future HOFer Al López named manager of Chicago White Sox

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Doug DeCinces

In 1968, Weaver began The Oriole Way in Baltimore

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Brooks Robinson

Future HOFer Al López named manager of Chicago White Sox