- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Brooks Robinson

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Brooks Robinson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

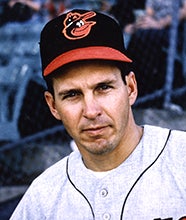

Fifty eight Hall of Famers have made their way to Cooperstown for the 2018 Induction Weekend. Among the returning Hall of Famers is an old favorite by the name of Brooks Robinson. Since his own induction in 1983, some 35 years ago, Brooks has become a regular at the weekend festivities. It’s safe to say that Brooks, who is as friendly and cordial as they come, makes each induction that much more inviting.

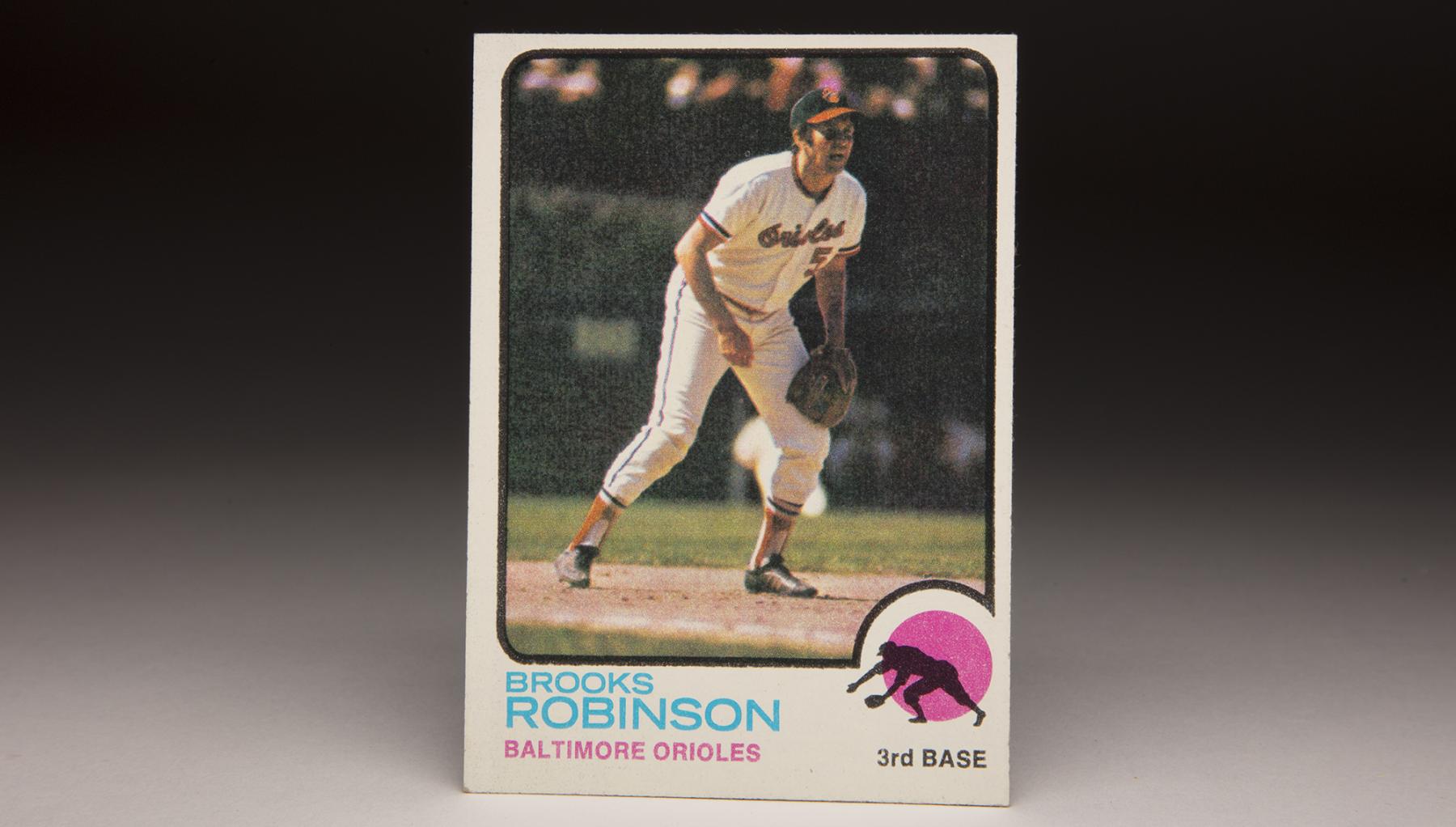

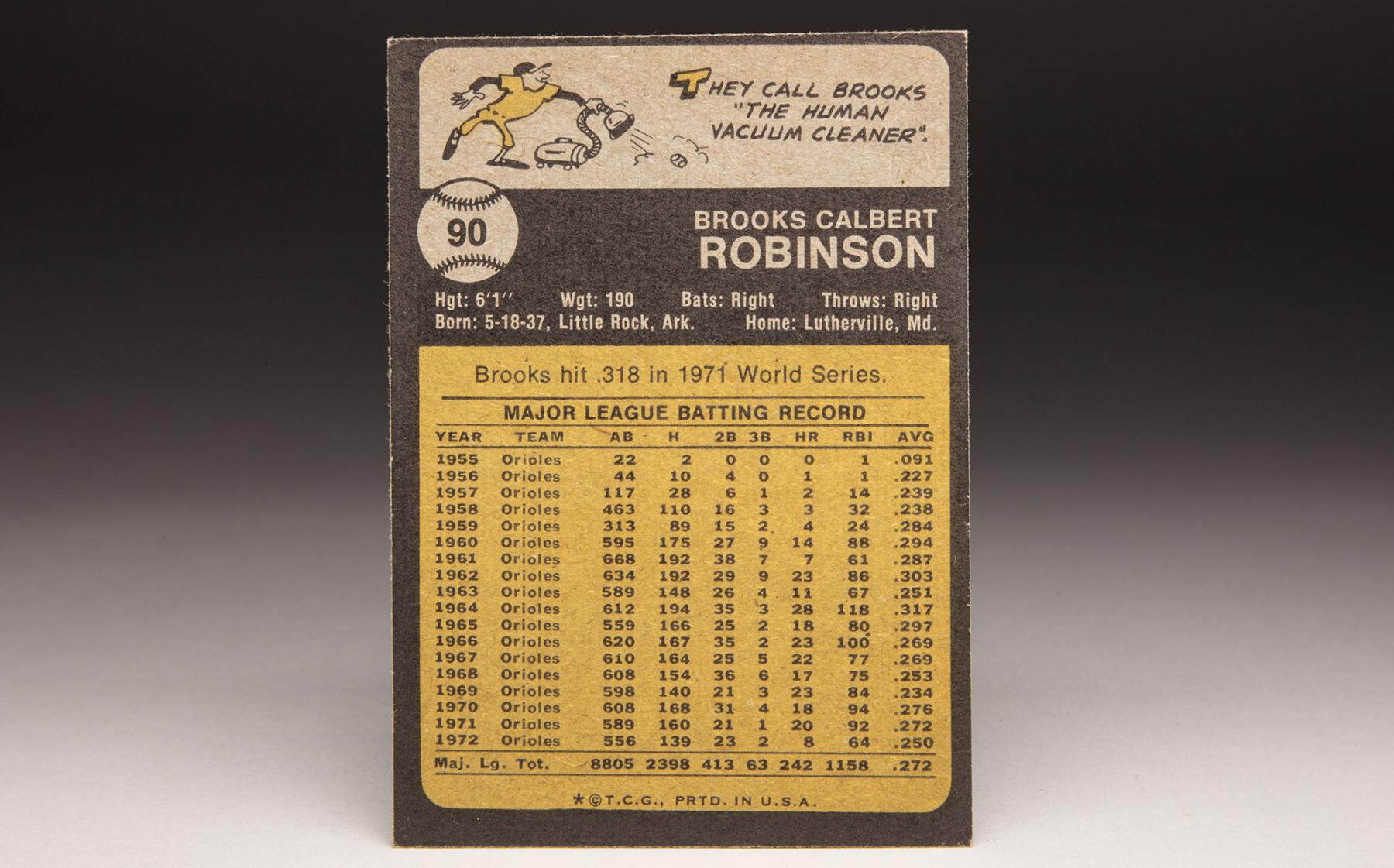

From 1957 through 1978, Brooks Robinson appeared on a bevy of cards produced by the Topps Gum Company. Remarkably, only one of the cards showed Robinson taking a defensive position in actual game action. (His 1976 card shows him holding a glove and a ball, but it is clearly a posed sideline shot, and not one taken from game action.) Given Robinson’s status as the standard bearer for third base play, there is something highly incongruous about the relative absence of cards showing him fielding the position known as the hot corner.

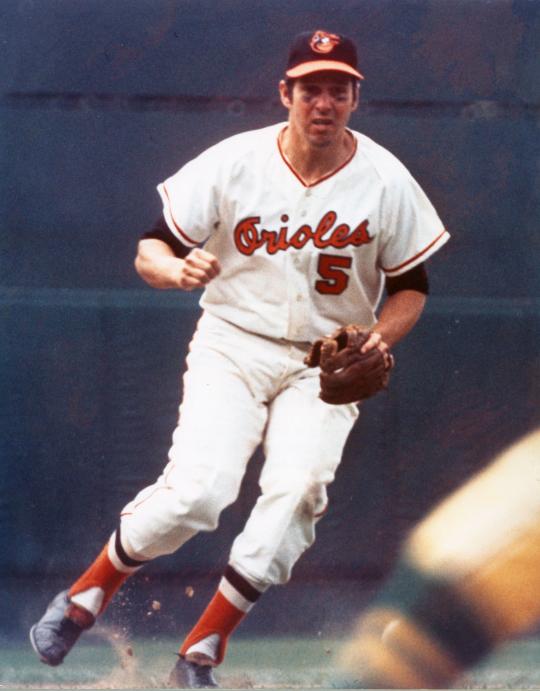

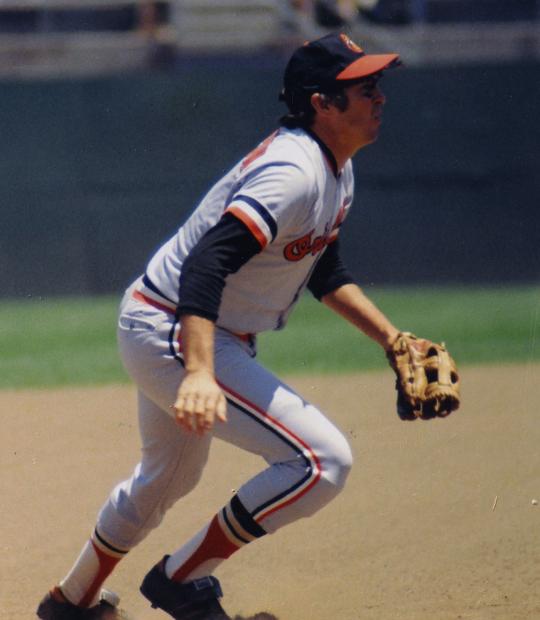

The only card that shows him playing third base comes from 1973 Topps. Perhaps that is why the ’73 card is my favorite depiction of Robinson. Seen in an unknown game from the 1972 season, Robinson appears ever alert in the field, his head up, and his body on the verge of crouching down, so that he can take his at-the-ready defensive stance. His right foot is perched on his toes, not on his heel, while his arms are anxious to embrace the next batted ball. Clearly, he is fully prepared to play the position that he has mastered, the one that fit his unique skills to seeming perfection.

Amazingly, third base eluded Robinson at the beginning of his career. When the Baltimore Orioles signed Robinson for $4,000 in 1955, they found him playing another position – second base – in a local church league. Paul Richards, the Orioles’ general manager, received two reports on Robinson’s talents – reports that conflicted directly with each other. “One of (the scouts) said he couldn’t run, throw, or hit, and couldn’t play,” Richards later told the Baltimore Sun. “The other scout said he could play.” Fortunately, Richards listened to the latter scout.

All of the scouts agreed that Robinson ran slowly, but Richards felt that his relative lack of footspeed was a minor concern, and not a complete indictment of his talents coming out of high school. Originally, the Orioles played Robinson at second base in the minor leagues, but they realized that he lacked the range for the position. In the middle of his first pro season, they moved him to third base, a better fit for a player who could move quickly (if not fast) and could make the long throw across the diamond.

In 1955, the Orioles assigned the 18-year-old Robinson to Class B York of the Piedmont League. Robinson was hardly a heralded can’t miss prospect; in his first at-bat, the public address announcer introduced him as “Bob Robinson.”

Brooks laughed that off and proceeded to hit .331 at York, playing so well that he earned a quick call-up to Baltimore at the end of the season. But he struggled for the Orioles, an indication that he was clearly not ready. The same pattern continued in 1956: a strong minor league campaign followed by a late and unimpressive cup of coffee with the Orioles.

In 1957, Robinson started the season with the Orioles before being sent back to the minor leagues. In 1958, the Orioles again rushed Robinson and made him their Opening Day third baseman, even though he was still only 21 years old. The Orioles badly needed help at the position, given the retirement of incumbent George Kell, the future Hall of Famer.

As a rookie for the Orioles, Robinson hit only .238 with a mere three home runs. Wisely, the Orioles sent Robinson back to Triple-A Vancouver to start 1959; he proceeded to tear up the Pacific Coast League, hitting .331 in 42 games, despite a freak accident in which he caught his elbow on a dugout hook and opened up an enormous cut on his arm. By midsummer, the Orioles felt that he was healthy – and ready. They brought him back to Baltimore and watched him hit a respectable .288 over the balance of the season. That summer, Brooks met a stewardess named Connie Butcher, who would soon become his wife.

Then came the professional breakthrough of 1960. Starting the season at third base, Robinson hit .294 with 14 home runs. More impressively, he played third base with acrobatic flair, while displaying the range of a middle infielder. He not only won the Gold Glove Award, but also earned his first All-Star Game berth. Even more impressively, he finished third in the American League MVP race.

In 1961, Robinson played in all of Baltimore’s 163 games (including a tie) while often batting out of the leadoff position, an odd spot for a player with little speed. He batted .287 and continued to play a sublime third base, but his power at the plate dipped. He finished with seven home runs, an uncharacteristic total compared to the prime years of his career. Even with the lack of power, Robinson still made the All-Star team and again earned some votes in the MVP balloting.

After not hitting with power in ’61, Robinson looked like a new man in ’62. He hit a personal best 28 home runs, batted a tidy .306, and won his third consecutive Gold Glove Award.

After a downturn in 1963, Robinson assembled the season of his career in 1964. Playing in every Orioles game, he batted .317, hit 28 home runs and compiled 128 RBI, leading the league in the latter category. For the first time in his career, Robinson raised his power hitting to the same level as his all-world defense. Not surprisingly, the league’s beat writers voted him the MVP Award.

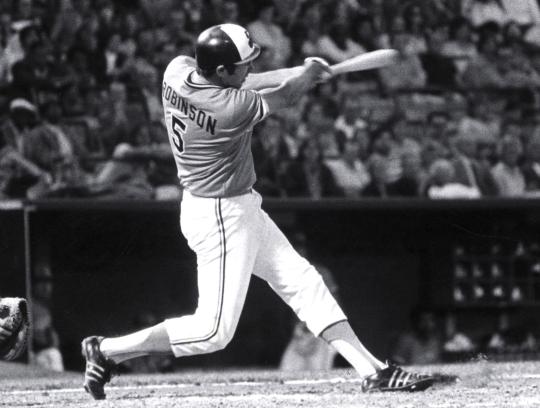

Robinson was now an established star and a household name. He was also becoming a recognizable player who wore a piece of equipment that was singularly unique. Early in his career, he had suffered a beaning on a high fastball; he felt that the incident occurred because the bill of his helmet obstructed his view of the pitch. In response, Robinson made an unusual change to his helmet, sawing off the outer edge of the bill and reducing its size.

The adjustment not only cleared up Robinson’s ability to track pitches, but it also left him with his trademark look at bat: an unusually short-billed helmet that could be spotted from hundreds of feet away.

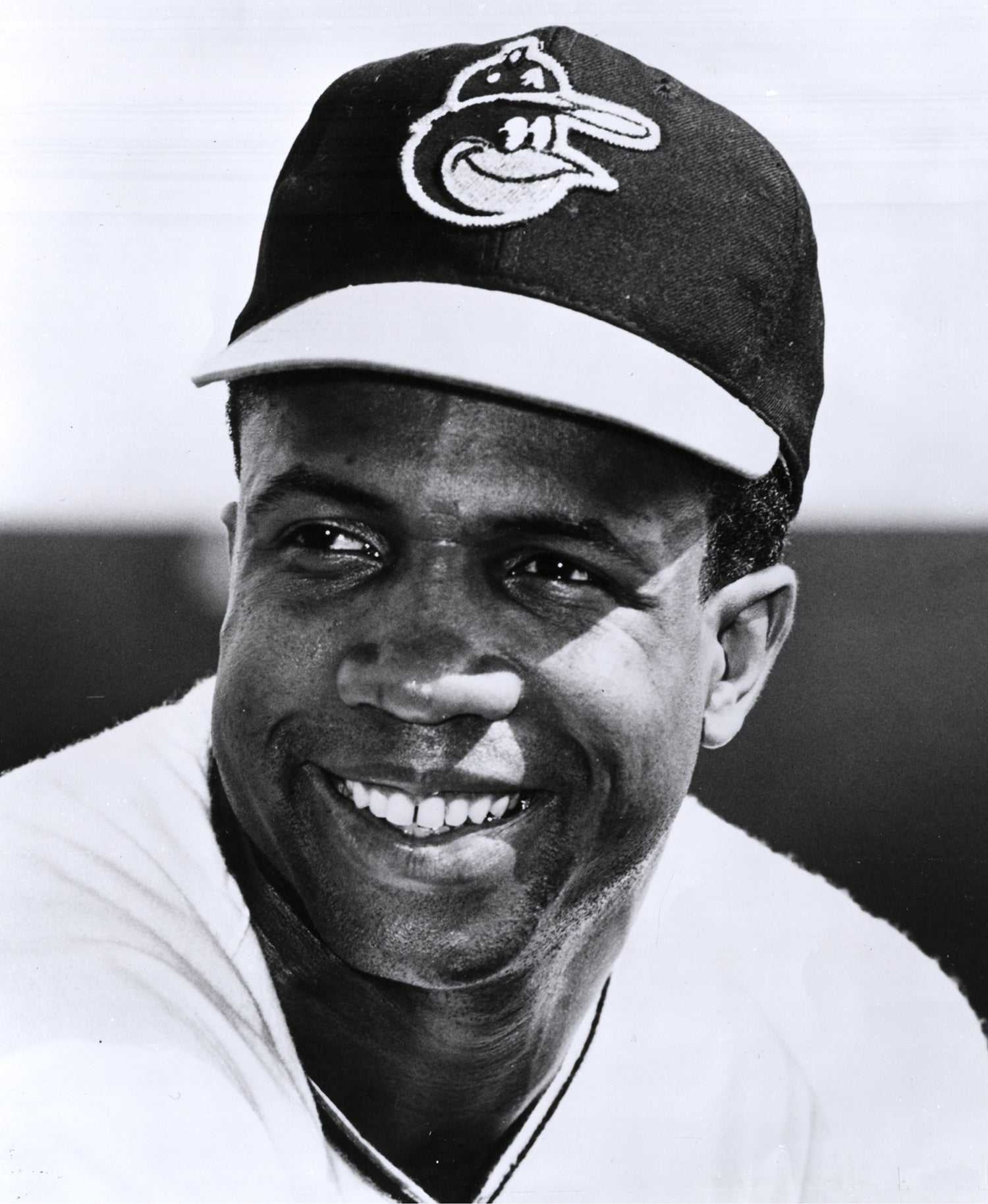

In 1966, Robinson received additional attention when he emerged as the standout player at the All-Star Game. He picked up three hits, leading the American League to victory and earning the game’s MVP Award. Even more significantly, he hit well during the ’66 regular season, reaching the 100-RBI plateau for the second time in his career. Brooks teamed with Boog Powell and the newly acquired Frank Robinson to anchor the middle of the Orioles’ order. Together, Brooks and Frank became known as the “Robinson Boys,” even though they bore no actual relation to each other.

After winning the American League pennant in a runaway, the Orioles faced the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series. Led by the two Robinsons and Powell, the O’s swept the Series. Offensively, Robinson hit a home run against Don Drysdale in the first game, helping Baltimore to a 5-2 win. Defensively, Robinson’s presence at third base discouraged the Dodgers from using the bunt, an important part of their offensive attack, throughout the Series. The Orioles won the Series, giving the franchise its first world championship since the move from St. Louis a decade earlier.

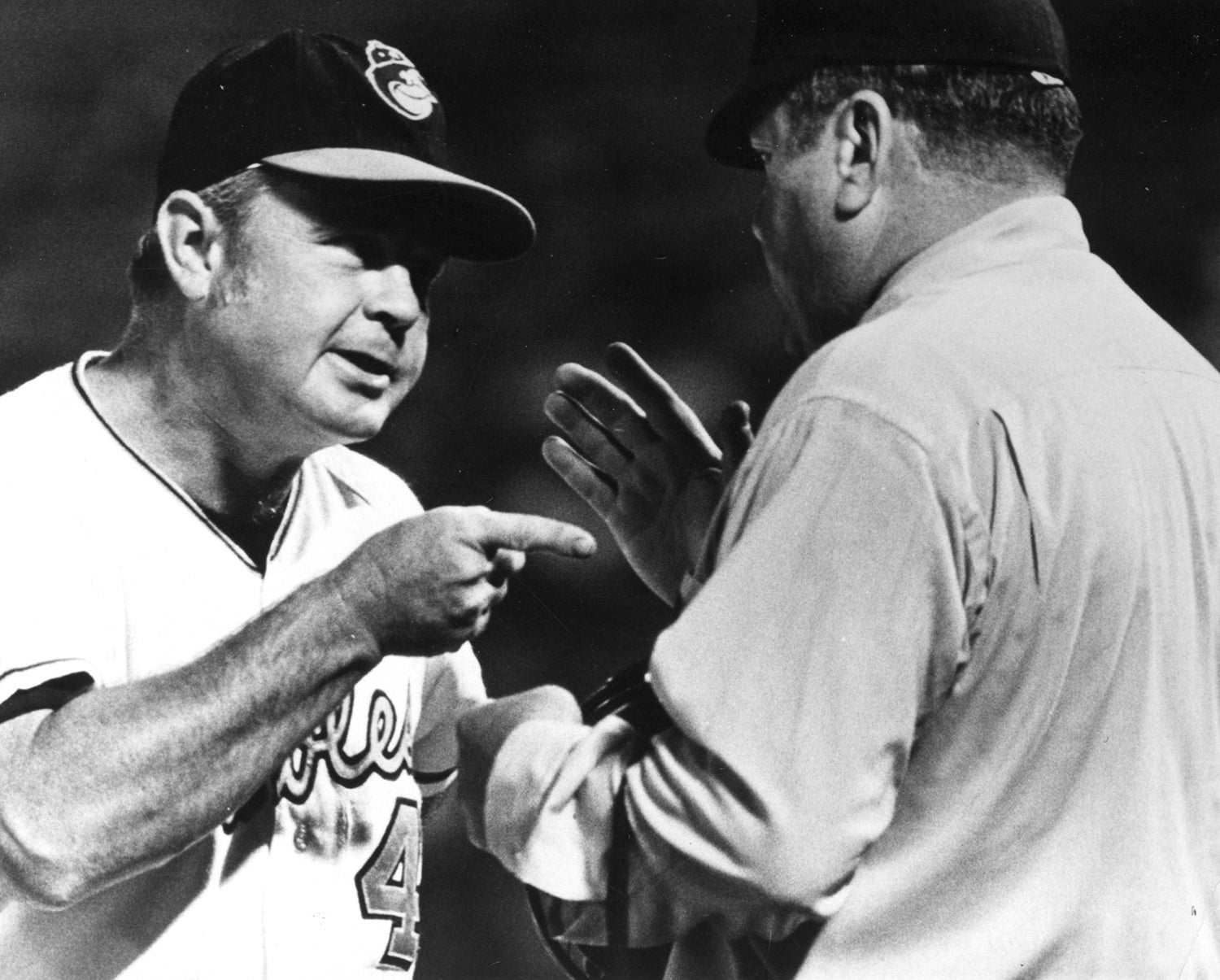

Playing in the World Series provided Robinson with national exposure. In particular, his fielding exploits took center stage. On the surface, Robinson didn’t appear particularly athletic, while also lacking the cannon arm of some third basemen. But a deeper look revealed a player with a quick first step on ground balls and the most accurate of throwing arms. And then there were his hands. Robinson gobbled up ground balls as if his hands were suction cups. Some people within the game began referring to Robinson as the “Human Vacuum Cleaner.”

From 1960 to 1969, Robinson won the Gold Glove Award every year, completing his domination of the third base position for the entire decade. In 1969, his fielding exploits helped the O’s return to the World Series, where they faced the upstart New York Mets. Like most of the Orioles, Robinson struggled against a Mets pitching staff headlined by Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Nolan Ryan, and Ron Taylor. Shockingly, the Orioles lost the Series in five games.

Robinson would gain some redemption in the 1970 postseason. The Orioles ran away with the American League and swept Minnesota in the ALCS. That set the stage for a World Series matchup between the Orioles and the Cincinnati Reds. With an overload of right-handed pull hitters who had enormous power, a group that included Johnny Bench, Lee May and Tony Perez, the Reds tested the 33-year-old Robinson with one searing line drive after another.

The 1970 World Series turned into the Brooks Robinson Flying Circus. In Game 1, Robinson somehow made a backhanded snare of a hard-hit grounder off the bat of May. The momentum of the play carried Robinson’s body into foul territory, but he stopped, spun around completely, and threw to first to finish off the remarkable play.

In Game 3, with runners on first and second and no one out, Perez hit a high-hopper that appeared headed toward left field. Robinson leapt, grabbed the ball at the peak of his jump, and stepped on third base to start a 5-3 double play. The next inning, Robinson charged a slow roller and made an off-balance throw to first base. And then in the sixth, Robinson robbed Bench by making a diving catch of a line drive.

By now Reds manager Sparky Anderson had experienced more than enough of Robinson. “I’m beginning to see Brooks in my sleep,” Anderson told reporters during one of his pregame press conferences. “If I dropped this paper plate, he’d pick it up on one hop and throw me out at first.”

Just on fielding alone, with nine putouts and 14 assists, Robinson ranked as the Series’ standout player. But he also provided an ample supply of hitting. For the Series, Robinson batted .429, hit two home runs, and totaled 17 bases. The writers made Robinson the logical choice to win the Series MVP. The Hall of Fame also showed its respect of Robinson by asking for his glove, which he gladly donated to the Museum. That glove remains on display in the Hall’s Autumn Glory exhibit.

As Robinson put on his one-man fielding extravaganza during the World Series, Lee May and several other Reds began calling him “Hoover,” a reference to the popular vacuum cleaner of the early 1970s. It was a natural way to shorten his previous nickname of The Human Vacuum Cleaner. Perhaps if Robinson played in today’s game, he would be known as “The Shark.”

As much attention as the 1970 World Series brought Robinson, he remained a top-tier player in 1971. In helping the Orioles win their third consecutive pennant, he hit 20 home runs, won his 12th consecutive Gold Glove Award, and finished fourth in the MVP balloting.

Robinson would never again reach double figures in home runs, but he remained an excellent fielder, even as his range diminished. He won four additional Gold Glove Awards from 1972 to 1975, giving him a total of 16 trophies for his collection.

By 1975, Robinson’s hitting skills had diminished. He hit only .201, marking the end of his days as an everyday player. The Orioles brought him back as a reserve in 1976 and ’77, mostly to serve as a tutor to his replacement, a young Doug DeCinces. On Aug. 13, Robinson played in his final major league game. A little more than a month later, the Orioles honored him with “Thank Brooks Day.”

With the finish of his career, Robinson had played 23 major league seasons, all with the Orioles. That stretch of longevity tied him with another Hall of Famer, Carl Yastrzemski of the Boston Red Sox, for the most years played with one big league club.

Six years after his retirement, Robinson entered the Hall of Fame, making his induction speech before a throng of people that filled Cooper Park, outside of the Hall’s Library. An extremely popular player with fans, he drew thousands of Baltimore residents to Cooperstown, at a time when the induction usually drew smaller crowds than it has in more recent years.

As a player, Robinson had a reputation for being the All-American boy, a model of behavior and honesty. He was close to his teammates, considerate and respectful with reporters, and always friendly with fans. So it should come as no surprise that Robinson, long since retired and long since enshrined, maintained that high level of character over the years.

It was through his election to the Hall of Fame that I eventually became fortunate enough to meet Robinson. Meeting Brooks is one of those wonderful experiences that only confirms why fans love the game. Whether it is merely saying hello as he enters the front door of the Hall of Fame, or conducting a full-length interview in the Grandstand Theater, Robinson always makes staff members feel welcome, as if we’ve known him since childhood.

As Orioles broadcaster Chuck Thompson once told Curt Smith in the book, "The Storytellers": “When fans ask Brooks Robinson for his autograph, he complied while finding out how many kids you have, what your dad does, where you live, how old you are, and if you have a dog.” Brooks simply wants to know.

Robinson passed away on Sept. 26, 2023, at the age of 86. He was an American treasure, not only as a pillar of playing third base, but as an ambassador for the game. Just how good of a man was Brooks Robinson? There’s an old saying that goes something like this, “They don’t make them any better than him.” Without question, that saying applies to Brooks Calbert Robinson Jr.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital & outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Brooks Robinson records 2,000th career hit

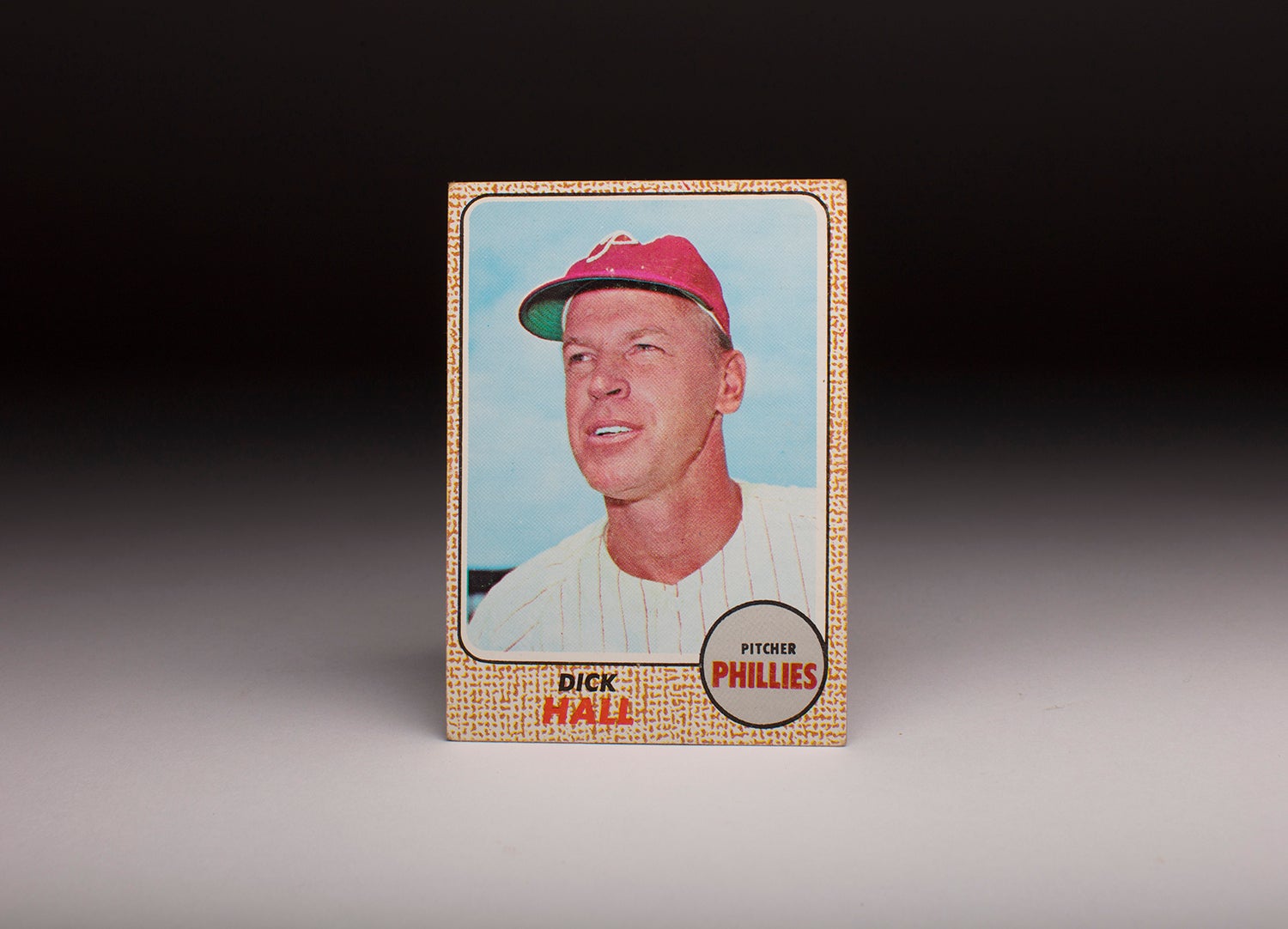

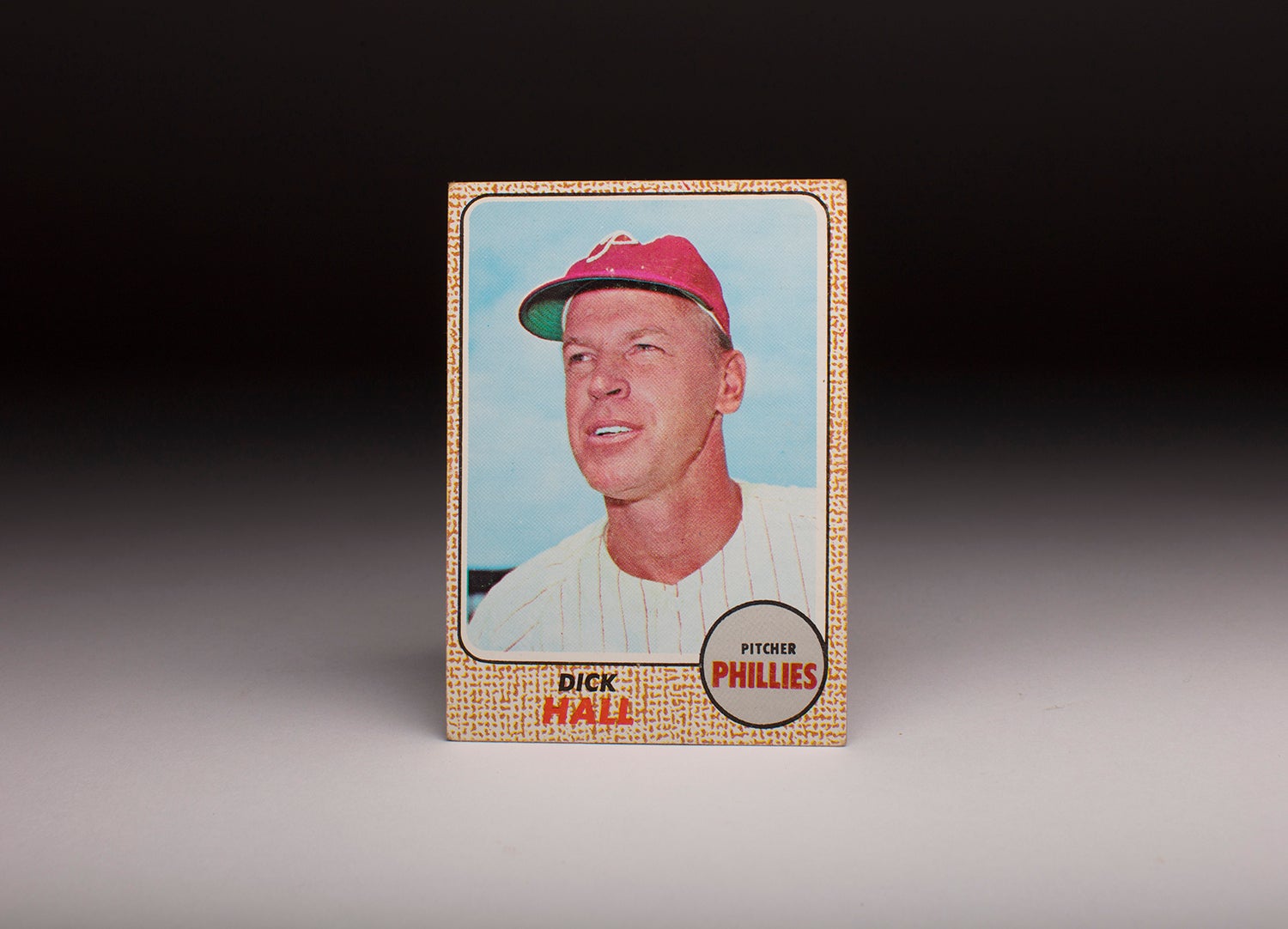

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Dick Hall

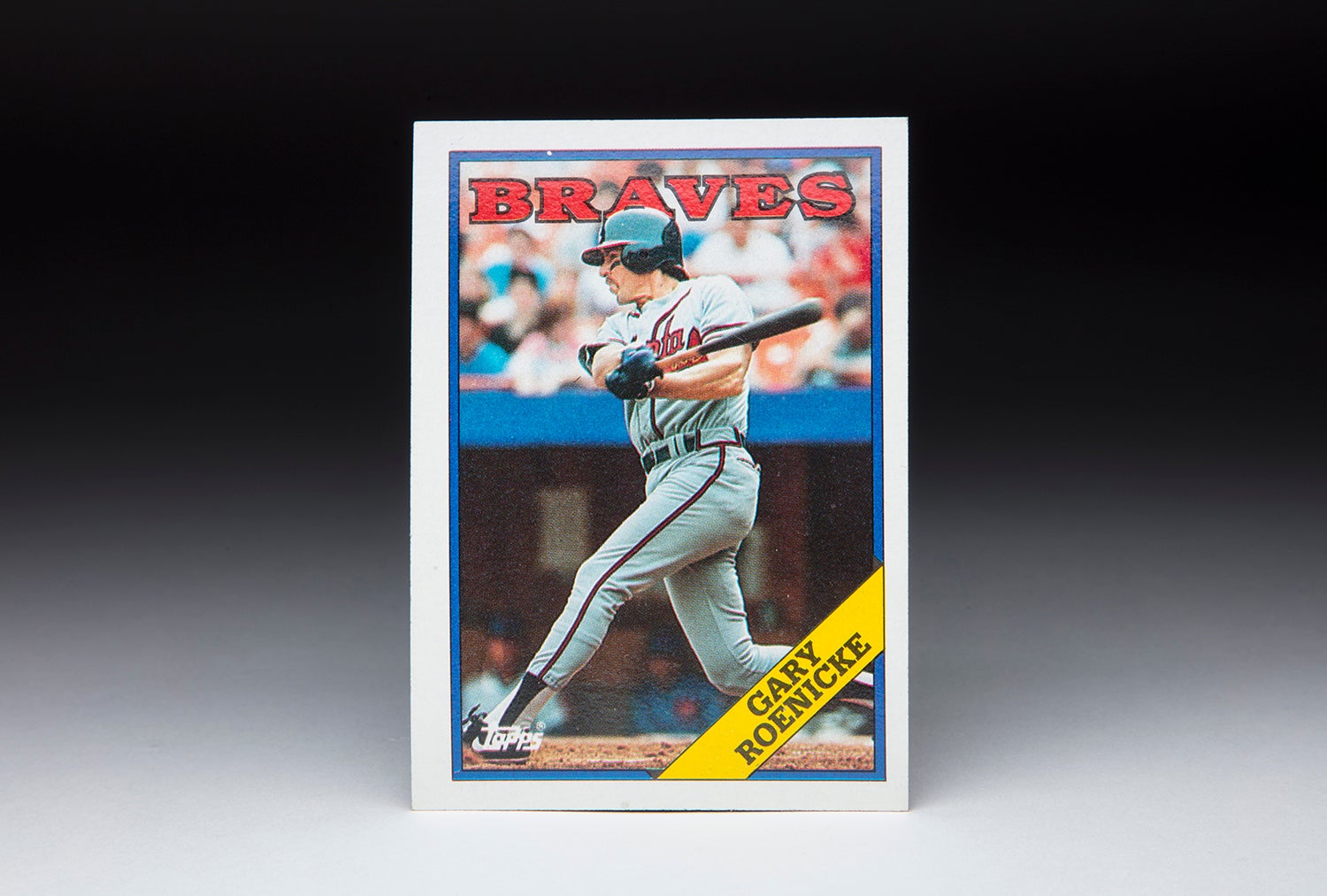

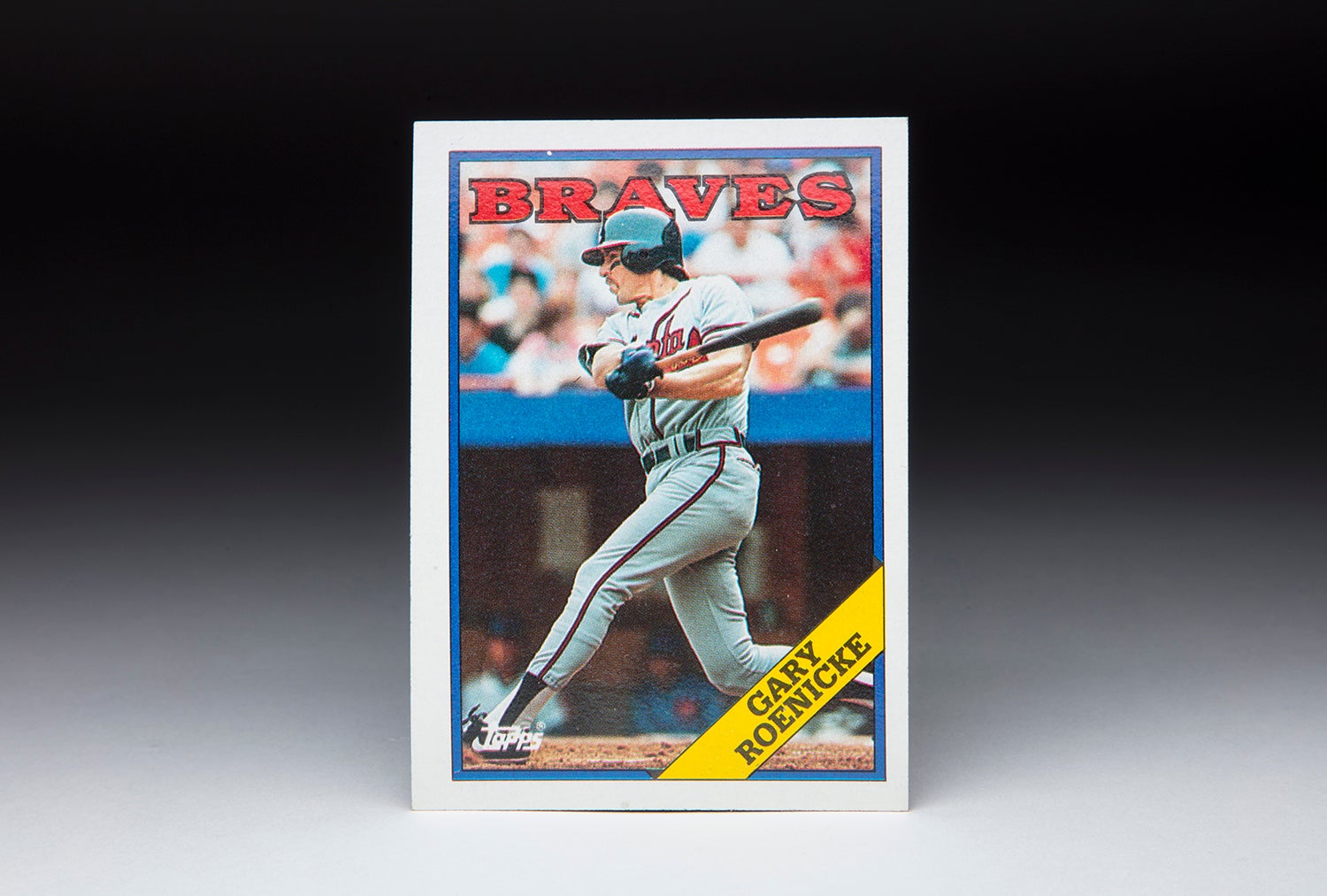

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Gary Roenicke

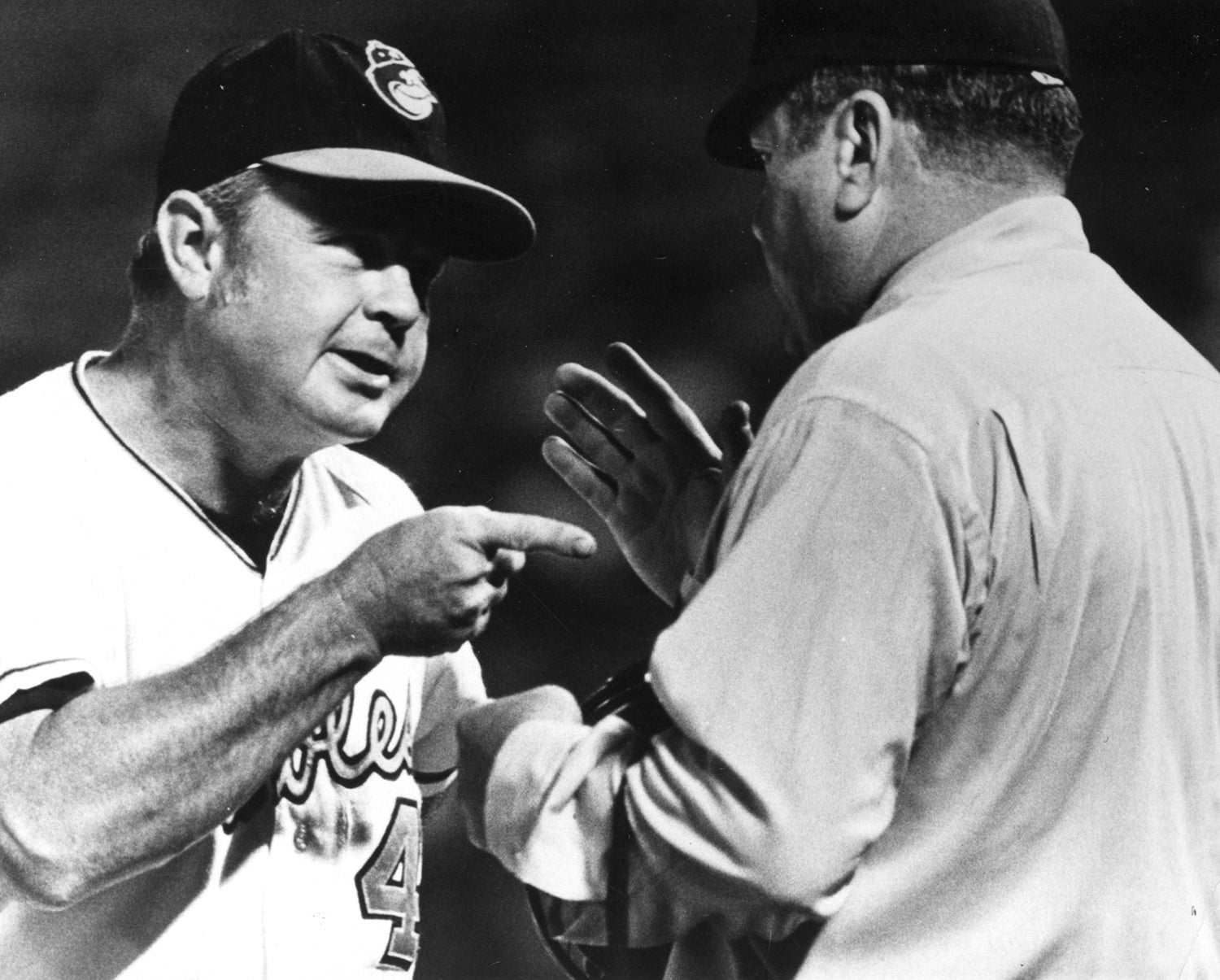

In 1968, Weaver began The Oriole Way in Baltimore

Brooks Robinson records 2,000th career hit

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Dick Hall

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Gary Roenicke