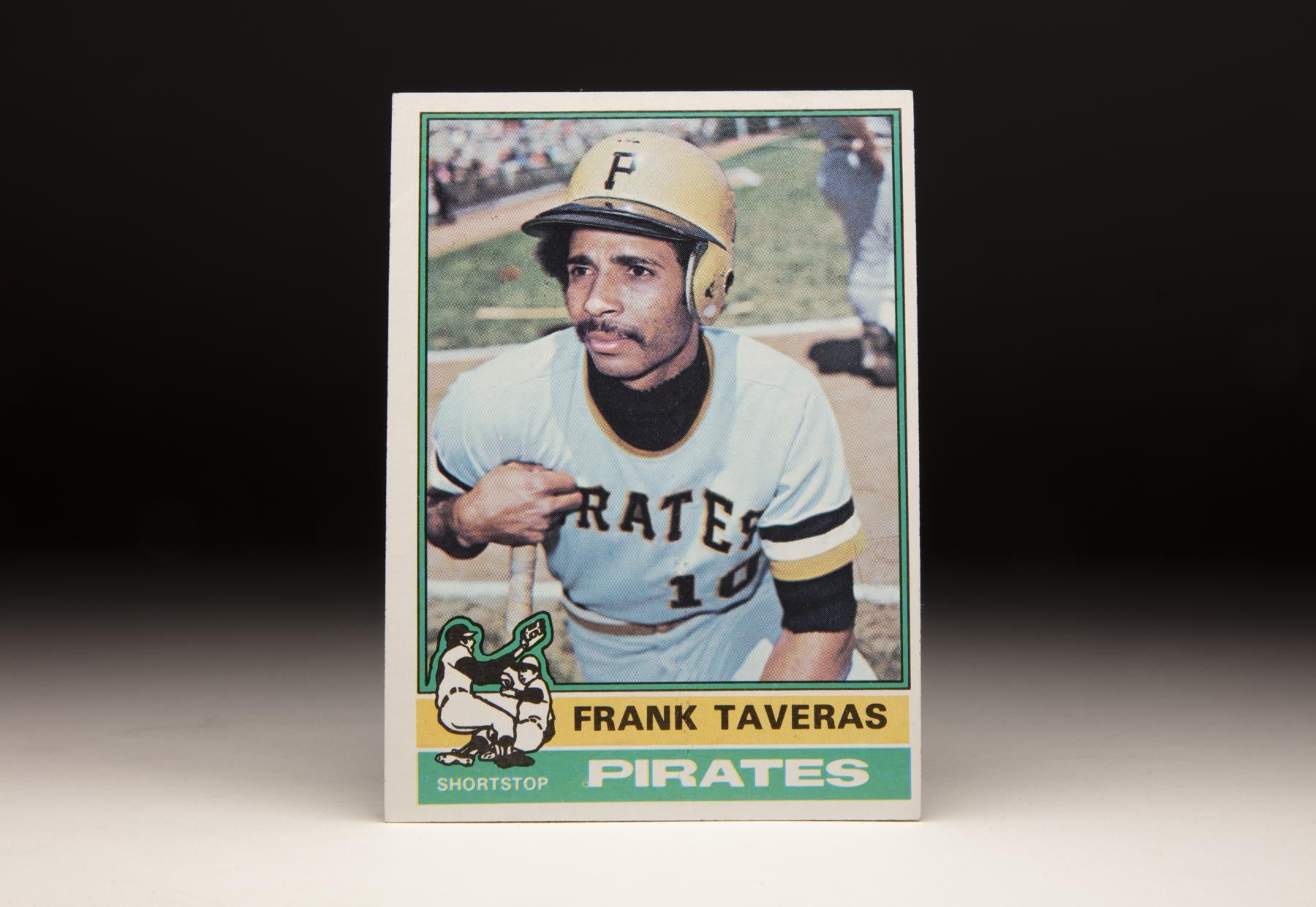

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Frank Taveras

Through a timely trade and a quirk in the schedule, Frank Taveras played in 164 games in 1979 – becoming one of only six players to top the 163-mark in a single season.

That trade also cost Taveras a chance to play in a World Series. But as the Pittsburgh Pirates’ primary shortstop of the 1970s, Taveras left his mark on one of the most successful teams of the era.

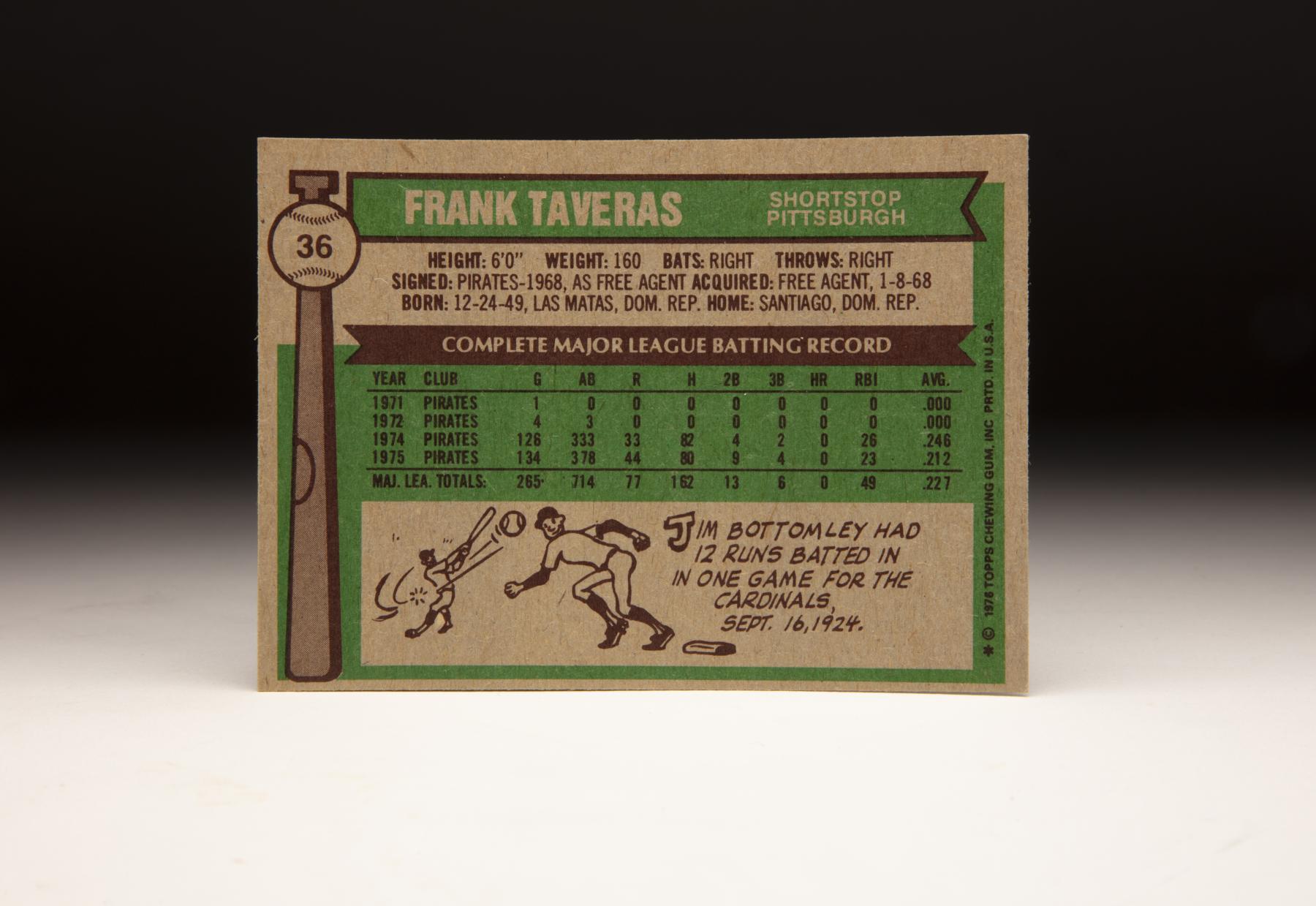

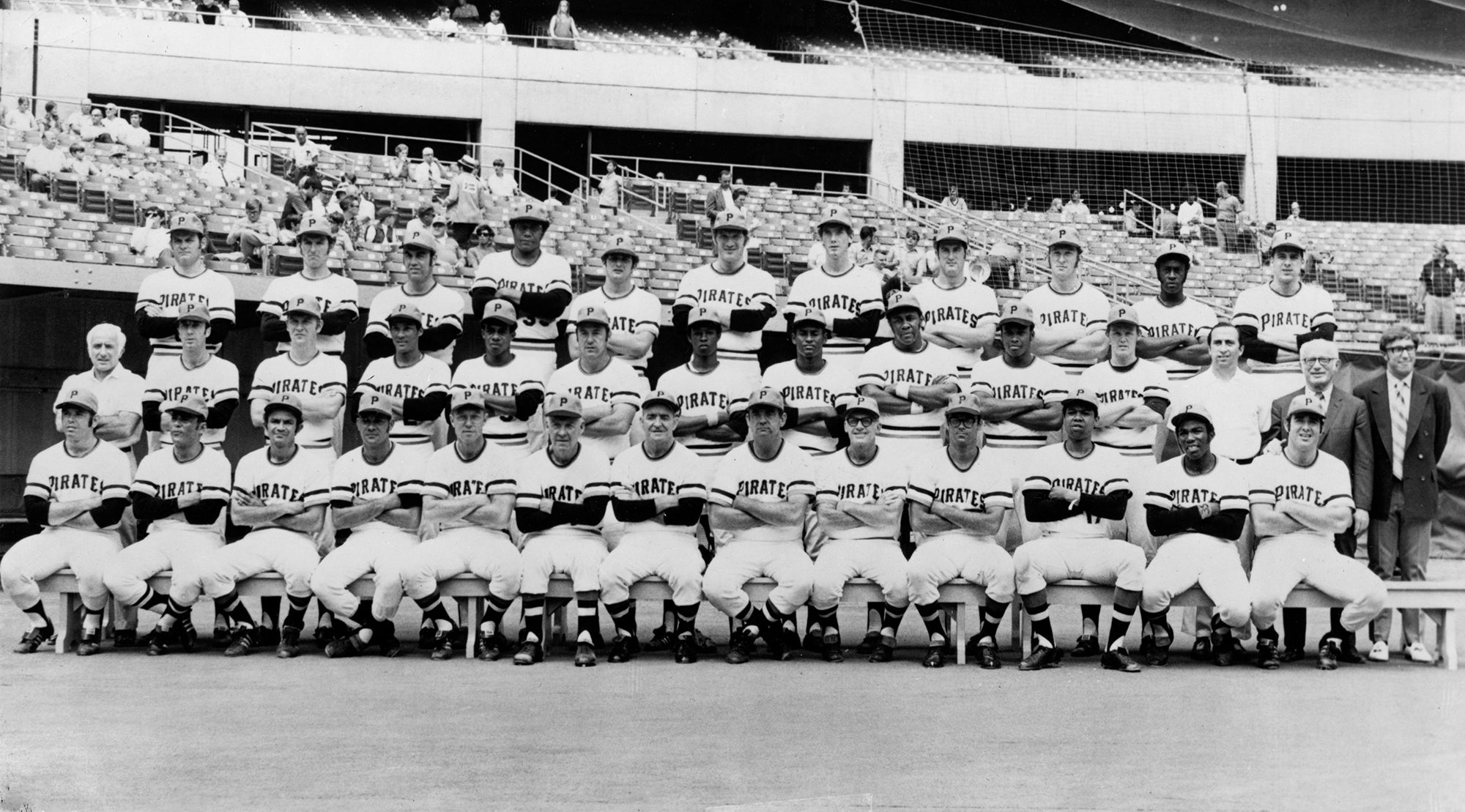

Born Dec. 24, 1949, in Las Matas de Santa Cruz in the Dominican Republic, Taveras – like many of his countrymen – played sandlot ball in the hopes of being discovered by a big league scout. Howie Haak, who became legendary for signing Latin American players like Manny Sanguillén, Omar Moreno, Rennie Stennett and Tony Peña to Pirates contracts, brought Taveras into the Pittsburgh system on Jan. 8, 1968.

Taveras played at three low-level minor league stops in 1968, hitting .254 with 14 stolen bases in 49 games. Then in 1969, Taveras again played for three teams – this time all at Class A – hitting .222 in 113 games. But defensively, he averaged almost 4.75 chances per game, showing off the range that would become his calling card.

In 1970, Taveras spent the entire season with Gastonia of the Class A Western Carolinas League, hitting .260 with 35 steals and 67 runs scored in 122 games. And while he made 37 errors at shortstop, those came in an impressive 567 chances – earning Taveras a berth on the league All-Star team.

Following the season, the Pirates put Taveras on the big league roster. He started the 1971 campaign with Double-A Waterbury of the Eastern League, hitting .207 in 87 games before being called up to Triple-A Charleston.

After hitting .267 in 48 games with the Charlies, Taveras was summoned to Pittsburgh on Sept. 1. The Pirates were sailing toward a second straight National League East title but had received little production from shortstops Gene Alley or Jackie Hernández.

Taveras appeared in one game for Pittsburgh, pinch-running for Willie Stargell in the 15th inning against the Mets on Sept. 25 before being erased on a double play ball. He was not included on the postseason roster as the Pirates beat San Francisco in the NLCS and Baltimore in the World Series, with Hernández making several key plays.

Taveras, however, was considered the Pirates’ shortstop of the future.

“I like that Taveras kid,” said Danny Murtaugh, who managed the Pirates to the 1971 World Series title but stepped aside in favor of Bill Virdon after the Fall Classic. “He covers the ground at shortstop. Good fielders are hard to find.”

Taveras, meanwhile, was hopeful that he would soon have a starting job in Pittsburgh.

“I feel good about my chances,” Taveras told the Charleston Daily Mail in the spring of 1972. “I am hitting the ball well. If I keep it up, who knows?”

But Taveras spent almost the entire 1972 season in Triple-A, hitting .246 with 12 steals in 133 games while recording 411 assists – along with 30 errors – at shortstop. He appeared in four more games with the Pirates that September but again did not see action in the postseason, where the Pirates lost to the Reds in the NLCS.

By this time, many scouts had rated Taveras as the best fielding shortstop in the minor leagues. But the Pirates kept him in Triple-A for all of 1973, and Taveras hit .242 with 17 steals in 145 games for Charleston.

In 1974, Murtaugh – back as Pittsburgh’s manager – had a tough decision at shortstop. Veteran Dal Maxvill was in camp, but most observers felt either Taveras or young Mario Mendoza would eventually win the job. With Taveras out of minor league options and Mendoza still optionable, Murtaugh kept Taveras on the Opening Day roster, played Maxvill in the first game and then moved Taveras into the starting lineup.

Taveras again fended off Mendoza for the starting shortstop job in 1975, and he cut his errors from 30 to 28 while accepting 75 more chances in the field. But Taveras’ batting average dropped to .212 as Murtaugh continued to pinch-hit for him in key situations.

Taveras was the target of frequent boo birds in Pittsburgh and feuded with them at times. On other days, Taveras seemed hurt by the booing.

“The fans pay their money, they’re entitled to boo,” Taveras told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “I don’t understand sometimes why they come after me.

“What really matters is that my teammates, my manager and the general manager know and like what I’m doing.”

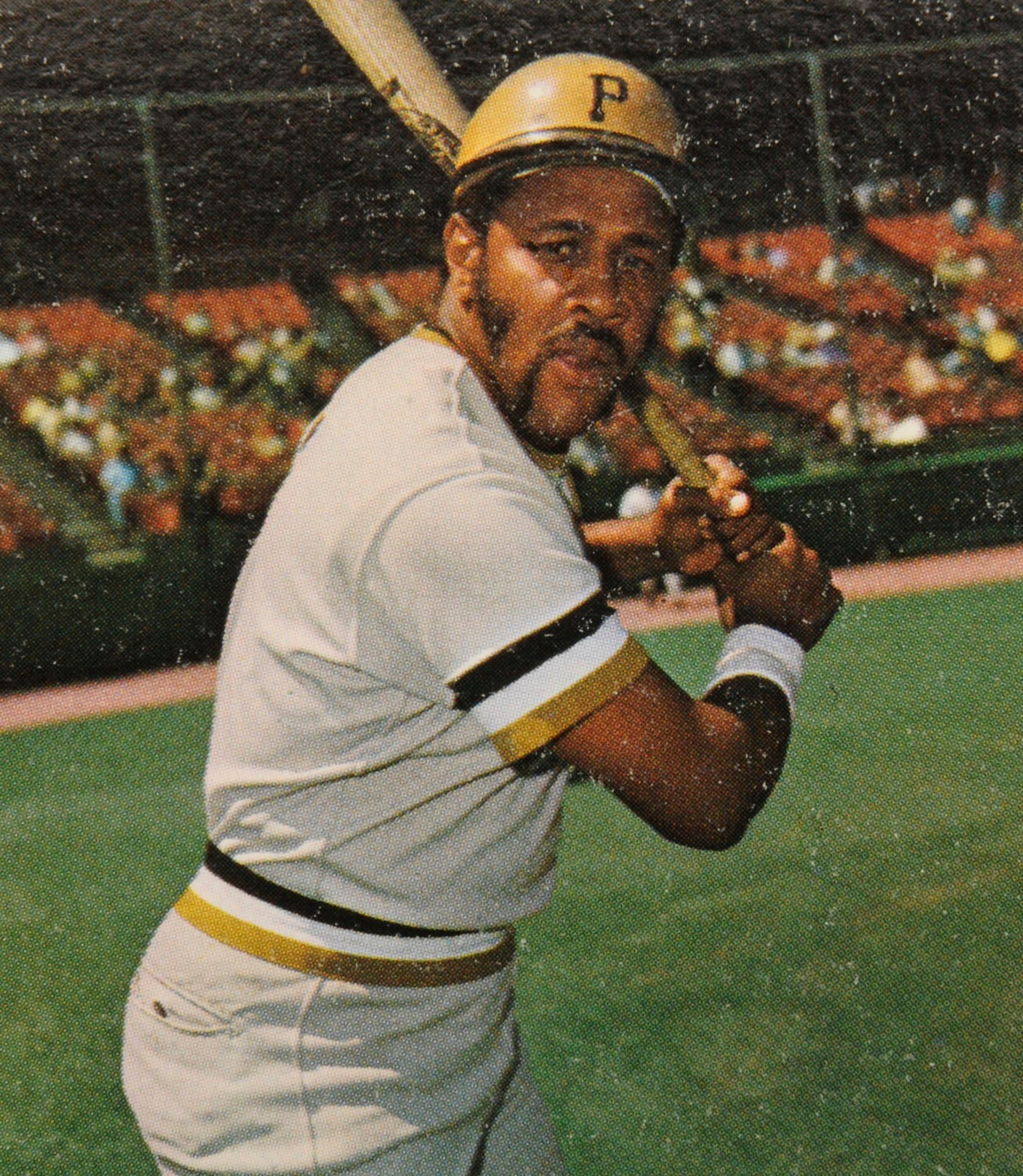

But in 1976, Taveras began to find some traction at the plate. Tagged “The Lumber Company” in a new advertising campaign to start the season, the Pirates lineup featured sluggers like Al Oliver, Dave Parker, Richie Zisk and Stargell – and only Taveras, among the eight position-player starers, went unmentioned in the new ad. But Taveras began using his speed to his advantage and totaled 58 stolen bases, just five short of the Bucs’ modern era record set by Max Carey in 1916.

“He was the most improved player in (Spring Training),” Tanner said of Taveras on Opening Day of 1978. “He was a different man.”

Taveras had his best season in 1978, hitting .278 in 157 games with 182 hits, 81 runs scored, 31 doubles, nine triples and 46 steals.

“I’ve never felt as good as I do now,” Taveras told the Pittsburgh Press at the start of the 1978 season. “Before I always played baseball in the winter. That always killed me. Now I feel strong. I also feel more relaxed.

“My goal for this season is not to lead the league in stolen bases but to help my team. I can do that by scoring more runs.”

But the Pirates didn’t win the NL East in either 1977 or 1978 and opened the 1979 season with a sluggish start. On April 19 – looking for a spark – Pirates general manager Harding Peterson sent Taveras to the Mets in exchange for Tim Foli and minor league pitcher Greg Field.

The trade was not met with much enthusiasm in the Pittsburgh media, where many bemoaned the trade of Mendoza following the 1978 season and others felt Foli – who was on the bench with the Mets – would not provide the offensive lift that Taveras could.

Meanwhile, Howie Haak – the scout who signed Taveras – immediately rated the deal as favoring the Mets.

“I thought we were giving up too much range in Taveras,” Haak told UPI. “As it turned out, people in New York say that Taveras is playing the best shortstop the Mets have ever seen.”

But Foli hit .291 with 65 RBI in 133 games for Pittsburgh, stabilizing the infield – he made only 15 errors all season compared to 38 for Taveras in 1978 – while making a habit out of clutch hitting. And the Pirates won the World Series.

Taveras, on the other hand, was as busy as almost anyone in the history of the game. He appeared in each of Pittsburgh’s first 11 games of the season before heading to New York, where the Mets had played just nine games through April 19. Appearing in New York’s 10th game of the season on April 20, Taveras played in 153 games for the Mets, including 17 doubleheaders. He missed only one game the rest of the season – the Mets played 163 games that year due to a tie – and joined a small list of players who have appeared in more than 163 games in any campaign.

Taveras finished the season with a .262 batting average, 93 runs scored, 29 doubles and 44 stolen bases. He set a career high with 779 chances in the field, committing 28 errors while stringing together an errorless streak covering 38 games. His .964 fielding percentage was a career-high.

“Frankie was part of us,” Stargell told The Record of Bergen, N.J., in the spring of 1980, “as much as anyone else.”

But Taveras seemed much more at ease in New York.

“I got a new start here,” Taveras told The Record. “New city, new team, new teammates. I needed to start again.”

Taveras had another productive season in 1980, batting .279 with 27 doubles and 32 steals in 140 games while committing only 25 errors. But the Mets lost better than 94 games for the fourth season in a row and were starting a rebuild that would result in their powerhouse teams of the mid-1980s.

Taveras slumped to a .230 batting average in 1981 and was charged with 24 errors in just 79 games at shortstop. On Dec. 11 – with prospect Ron Gardenhire ready to take over at shortstop – the Mets sent Taveras to the Expos in exchange for pitcher Steve Ratzer and cash.

“They say I didn’t field well in New York, but we had a bad field,” Taveras told the Ottawa Citizen about the playing surface at New York’s Shea Stadium. “The (NFL’s) Jets were on it all the time chewing it up. I know every time I played in Montreal, I fielded the ball well.”

But with veteran shortstop Chris Speier returning on a multi-year contract, Taveras found little playing time. He hit .161 in 48 games before the Expos released him on Aug. 13, 1982. In October, the Pirates offered Taveras a minor league contract and an invitation to Spring Training in 1983, but the parties could not come to an agreement and the Pirates ultimately withdrew the invitation.

Taveras would never again play in the big leagues.

Returning to the Dominican Republic, Taveras worked as a scout for several years. His status among his countrymen was powerful: At the point where Taveras played his last big league game, only six players born in the Dominican Republic – Felipe Alou, Matty Alou, Jesús Alou, Rico Carty, César Cedeño and Julian Javier – had more at bats in the big leagues than Taveras.

He finished his 11-year career with a .255 batting average, 1,029 hits and 300 stolen bases.

“I’m going to show people,” Taveras told UPI in 1976 as he was entering the best years of his career. “Just practice and do the best you can.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum