- Home

- Our Stories

- Blockbuster trade brings Maranville to Pittsburgh

Blockbuster trade brings Maranville to Pittsburgh

For nearly two decades, beginning in 1900, the Pittsburgh Pirates enjoyed a standard of excellence at shortstop. They won two pennants in that span, dropping the World Series in 1903 before winning it six years later.

Pirates Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

But Honus Wagner, outstanding as he was, couldn’t play one of the sport’s most physically demanding positions or dominate at the plate forever. For the first time in his Pirates career, The Flying Dutchman failed to hit .300 in 1914, and by 1917 he was mostly a utility player. Wagner, 43, retired after that season.

Three years of uninspiring shortstop play followed. Then on Jan. 23, 1921, Pittsburgh pushed in its chips to acquire the franchise’s next Hall of Fame shortstop, dealing infielder Walter Barbare, outfielders Fred Nicholson and Billy Southworth and a reported $15,000 to the Boston Braves in exchange for Walter “Rabbit” Maranville, a 29-year-old with more than 1,000 National League games under his belt.

With the expectation that Boston would part with Maranville, several franchises had been eager to trade for the star shortstop.

“While many followers of the Buccaneers are rejoicing over the acquisition of one of the best and most peppery shortstops in the country, fans in other cities, where he was much wanted, are in mourning,” wrote the Pittsburgh Press. “Especially is this true of New York and Cincinnati, the Giants and the Reds having been ardent bidders for the little fellow.

“Considering the monetary value of the players involved, this transaction ranks as one of the biggest ever consummated.”

Yes, the Pirates had paid a hefty price for Maranville, dealing promising, productive players, the additional cash and even a future Hall of Fame manager in Southworth, but manager George Gibson was eager to fill his hole at shortstop.

“One man’s loss is another man’s gravy,” wrote the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

That said, the Braves, too, were satisfied with their returns.

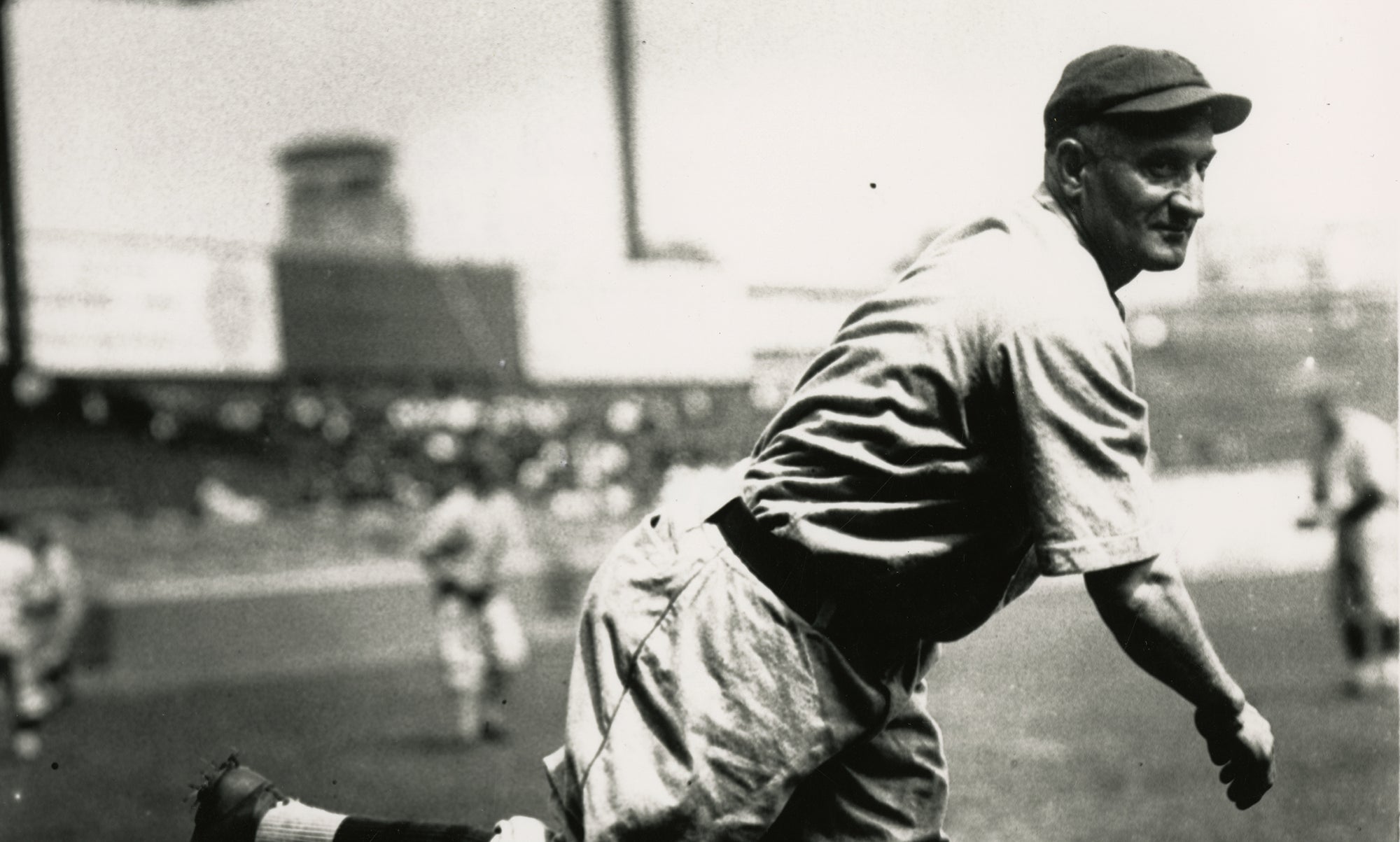

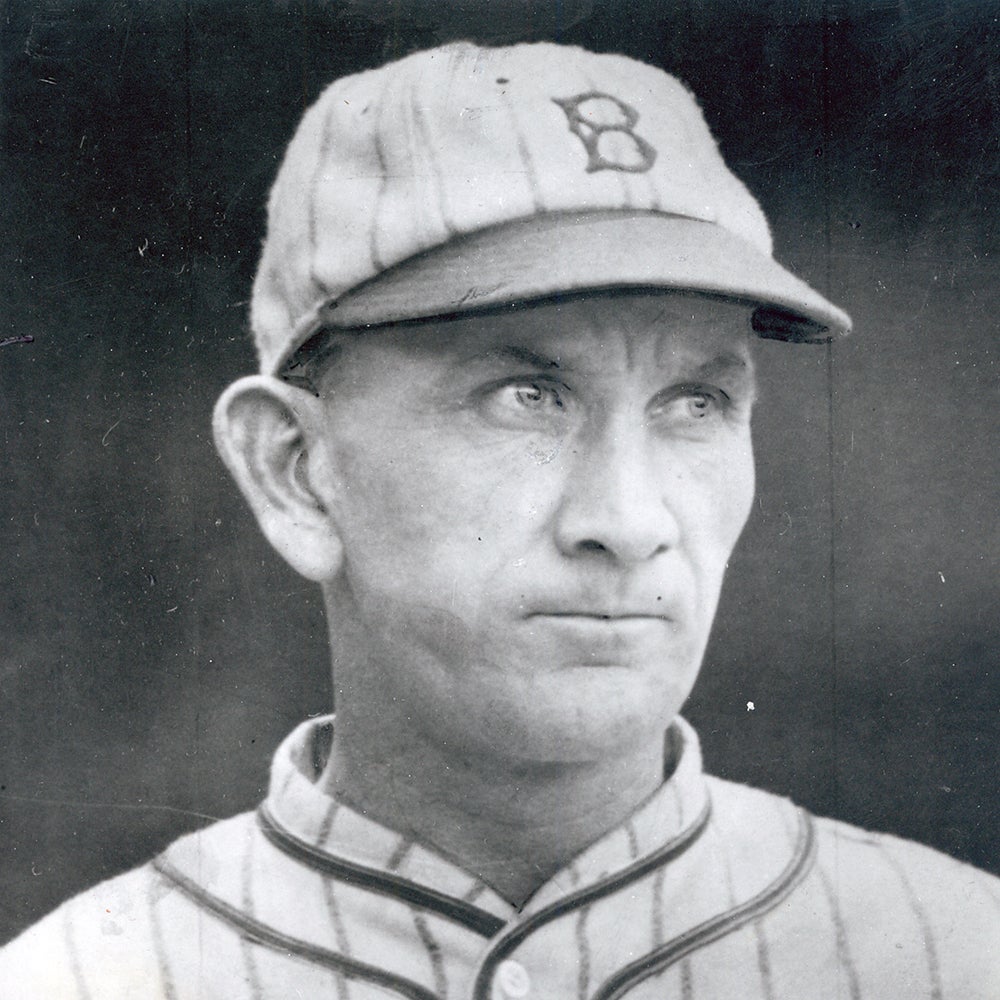

Rabbit Maranville began and ended his career with the Braves, hitting .252 with 194 stolen bases and 558 RBI across 15 seasons in Boston. (Charles C. Conlon/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“Nobody loves the Rabbit more than I,” said Boston manager Fred Mitchell. “But since we ought to build a baseball team we cannot allow sentiment to stand in the way… We have, I believe, obtained three great players for one.”

Maranville, meanwhile, hardly approved of the deal at first. “I want to play baseball in Boston more than in any other city,” he told the Associated Press. “I do not want to leave Boston and I do not want to go to Pittsburgh, and I don’t think I’ll go.”

Judging by his performance, Maranville certainly warmed up to the idea of playing for the Pirates. His 180 hits in 1921 were a career-best at that point, his .294 average second-best. Pittsburgh won 90 games, an 11-win improvement over 1920.

The returning assets played well for Boston, too. Barbare hit .273 with the Braves, Nicholson .291 and Southworth .315, but they were, at best, a fourth-place team in the 1920s.

And the trade provided nothing more than short-term gains for either side. By 1924, Nicholson and Barbare had retired while Southworth had been dealt to the Giants in a trade that returned another Cooperstown-bound legend, Casey Stengel.

Offensively and defensively, Maranville performed as advertised through the 1924 season, after which he was dealt to the Cubs in another multi-player trade. On Dec. 8, 1928, following brief stints in Chicago, Brooklyn and St. Louis, Maranville was reacquired by the Braves.

Back in Boston, he played out the final six seasons of his career before being inducted to the Hall of Fame in 1954.

Justin Alpert is a digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Story

Related Story

Related Stories

Marty Marion - No shortage of talent

Baseball, boxing intersected famously at Forbes Field in 1941

Writers Elect Four to the Hall for the First Time in 60 Years

Blockbuster trade brings Maranville to Pittsburgh

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

'Fastball' Headlines Tenth Annual Baseball Film Festival

With deliberate speed, the 1950s saw the reintegration of the white major leagues

When the First Five Were Chosen