- Home

- Our Stories

- A Game for the Ages

A Game for the Ages

One of the wonderful things about baseball is that it never ceases to amaze. Whether it’s a game from the current season or one from long ago, one constantly hears or sees things that defy logic and seem improbable as fact. On July 4, we celebrate the anniversary of one of these moments. It is a moment forever recorded as one of greatest pitching matchups of all-time.

Imagine a game featuring two future Hall of Fame pitchers, one of whom would become the winningest pitcher in the history of baseball, while the other was the biggest drawing card in early American League annals and played for arguably baseball’s best team of the era. Imagine a game that was the longest finished and untied game by innings up to that point in history. Imagine a game where both starting pitchers threw an estimated 250 to 300 pitches. Wrap that into the fact that it was the nation’s birthday with the game occurring in Boston, one of the cradles of American liberty, while the opposition represented the home of Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell. Mix that all together and you have the 20-inning classic between Boston’s Cy Young and Philadelphia’s Rube Waddell in which both went the distance at Huntington Avenue Grounds on July 4, 1905.

And that wasn’t even the first game of the day. In game one of the scheduled doubleheader, Waddell came on with one out in the ninth inning to preserve a 5-2 Athletics lead, earning a save by today’s rules. In the second game, the lanky and zany (some would say crazy) left-hander started off a bit shaky, allowing two runs in the bottom of the first. A’s first baseman Harry Davis tied things up with a two-run homer off Cy Young in the sixth inning. Then followed 13 innings of scoreless baseball as Waddell and Young went toe-to-toe. On several occasions the Americans got men to third base, but Waddell would work his way out of the jam each time. Philadelphia had its moments as well, but Young was able to beat them back.

In the top of the 20th inning, Boston’s defense finally let Young down. After some booted and misplayed balls (as well as a hit batsman), Waddell strode to the plate with the bases loaded. When his slow roller to short was misplayed, the A’s took the lead, and they tacked on another run to lead 4-2. Waddell took to the mound in the bottom of the 20th intent on preserving the team’s lead (as well as his game-winning RBI, although RBI wouldn’t become an official stat for another 15 years). With a man on second with two outs to go, he got the final two batters to pop up and the A’s won the game. Waddell did cartwheels around the mound in celebration.

He had pitched nearly 21 innings that day (with almost 20 scoreless), and had both won and saved a game. It was also sweet revenge for Rube, as the year before he was on the wrong end of Cy Young’s 3-0 perfect game victory pitched in the same park (the first perfect game of the modern era and current pitching distance). For Young’s part in the loss, he threw 18 scoreless innings and issued not a single walk in the 20-inning defeat, with the deciding runs both unearned. Waddell’s batterymate Ossee Schrecongost caught every pitch that day, with his 29 innings behind the plate still a single-day record.

Even at the time, all present knew they had witnessed something special. It became one of the most talked about games of a generation. As noted in the Philadelphia Inquirer, “the two teams kept at it with the excitement at fever beat until three hours and a half had been consumed, suppers forgotten, engagements neglected, trains and boats missed, for very few would allow anything to interfere with their presence at the finish of such a game.” The paper also called the matchup “the greatest performance in the history of the league.” Cy Young would later state that it was the greatest game in which he ever participated and “the greatest performance either of us has ever shown.” In terms of his thoughts on Waddell, Young reminisced in 1943 that “there’s no doubt about it, Rube Waddell was the best left-hander of all time.” A’s manager Connie Mack stated the same sentiment on a number of occasions. As for Rube, he immediately took the game ball home with him to Philly, which he promptly displayed in his favorite saloon, in trade for free drinks. Amazingly many bars were soon “displaying” this trophy ball simultaneously.

Young and Waddell would meet 14 times in their respective careers, and it seemed every game was a battle (including numerous shutouts). Yet their famous Fourth of July duel will rightfully go down as one of the best pitching contests of all time. In an age of specialized pitching roles, the remarkable feats of this game seem impossible by today’s standards. Yet, as we all know, truth is often stranger than fiction.

Erik Strohl is the vice president of exhibitions and collections at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Reproductions

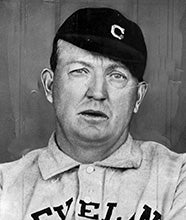

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum features a collection of nearly 250,000 photographs like this one. Reproductions are available for purchase. To purchase a reprint of this photograph or others from the Photo Archive collections, please call (607) 547-0375 or email jhorne@baseballhall.org. Hall of Fame members receive a 10-percent discount.

Online Photo Exhibits

Support the Hall of Fame

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Just the Ticket for Cobb

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

Mathewson Throws Third Shutout in Series to Take Title

Chip off the Block

Reese joined Dodgers teammates in Cooperstown in 1984

Greatness Defined

A week from Induction, Griffey & Piazza savor the moment

BA MSS 67, Folder 15, Corr_1946_4_9b

01.01.2023

Two-time Cy Young Award-winner Gaylord Perry reflects on making history in both leagues

01.01.2023