- Home

- Our Stories

- Mays’ Candlestick Park locker a priceless addition to Hall of Fame

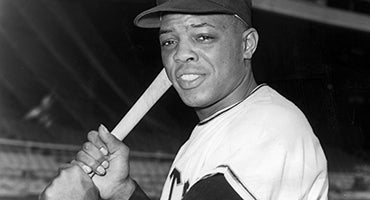

Mays’ Candlestick Park locker a priceless addition to Hall of Fame

The Candlestick Park locker used by Willie Mays for more than a dozen seasons, a place where he spent countless hours with teammates and the press, is now part of a historic new exhibit at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

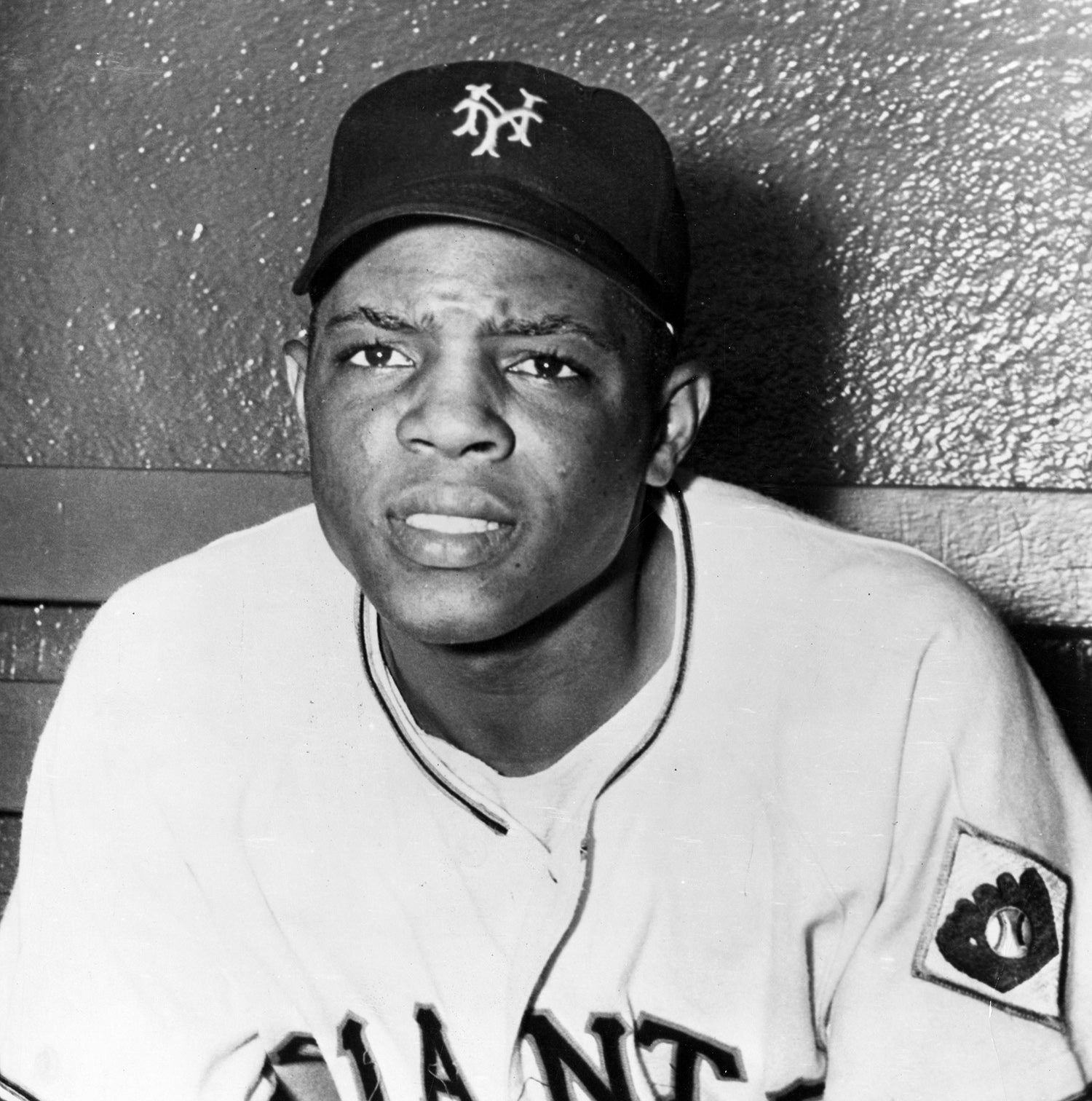

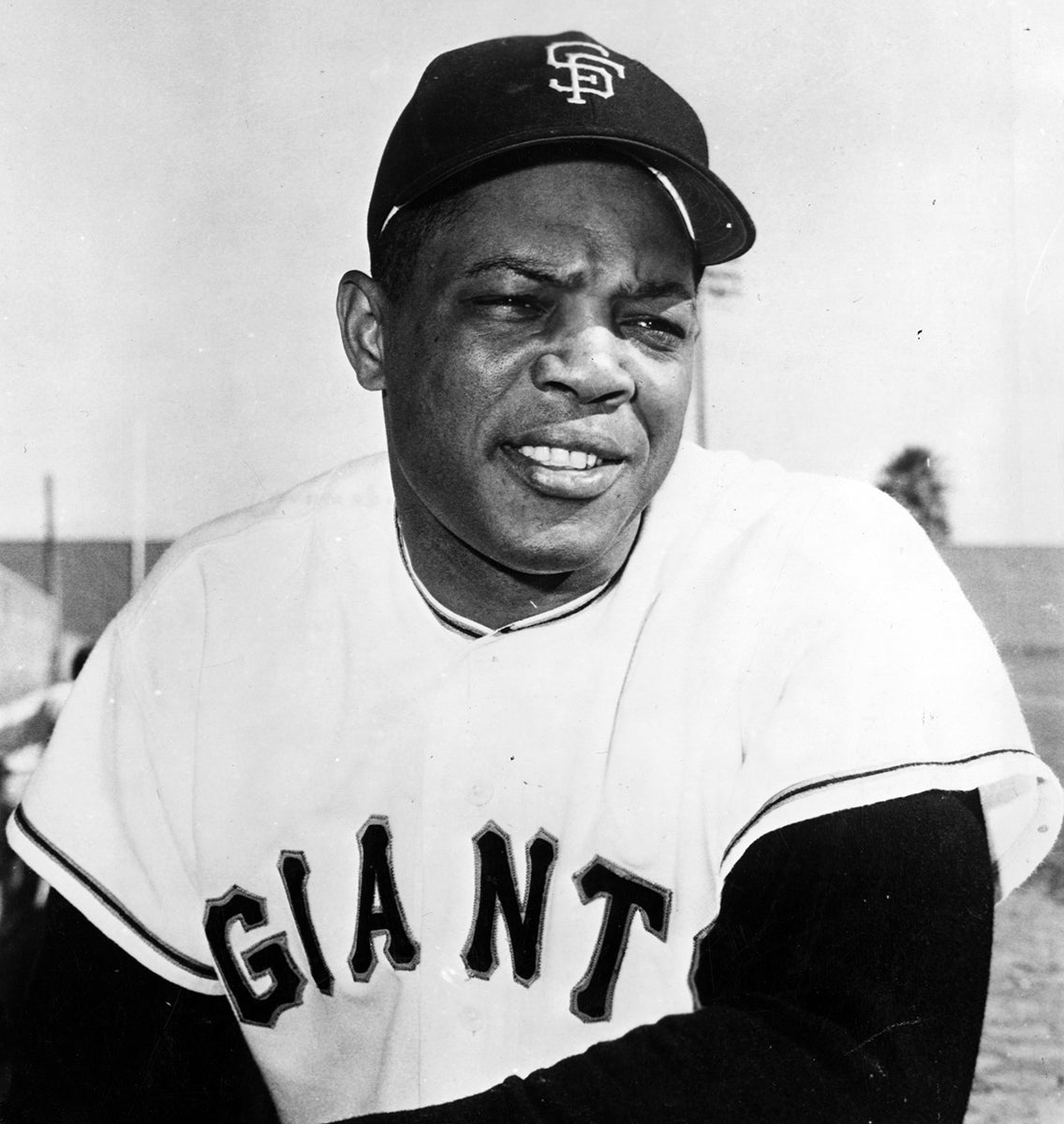

Mays, who passed away on June 18 at the age of 93, was one of the sport’s most electrifying and beloved players. The center fielder, known for his trademark basket catch, was a five-tool player whose passing reverberated both inside and outside the baseball world.

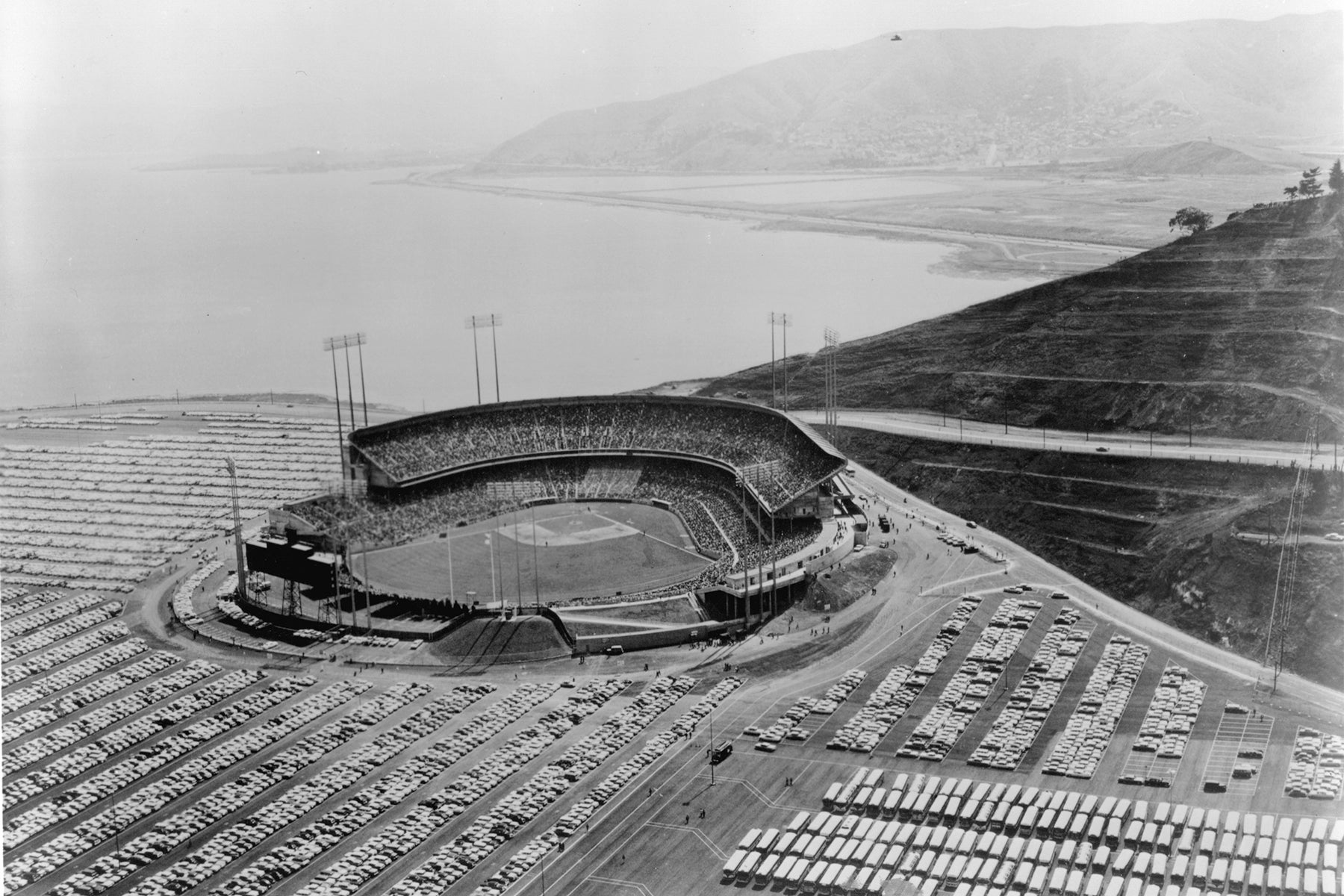

In 2023, longtime football coach and current broadcaster Steve Mariucci generously donated the Candlestick Park locker used by Mays while a member of the San Francisco Giants from 1960 to ’72. It was later the locker used by Barry Bonds, Mays’ godson, from 1993 to 2000.

Today, Mays’ locker can be found in The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball, a groundbreaking exhibit on the Museum’s second floor that opened Memorial Day weekend. It shares the decades-long history of Black baseball prior to the formation of the Negro Leagues, through the complexities of baseball’s re-integration, to the challenges that remain today.

“We are so grateful that Steve thought of us as the perfect spot to donate this incredibly unique artifact,” said Hall of Fame President Josh Rawitch. “In just a single object, we are able to accomplish all three things we set out to do in our mission: Preserve History, Honor Excellence and Connect Generations.”

The wooden locker’s dimensions: 7 feet, 1 inch tall; 4 feet, 3 inches wide; 4 feet, 5 inches deep.

After the Giants left Candlestick, then known as 3Com Park, following the 1999 season for Pacific Bell Park (currently called Oracle Park), the Mays locker was removed and stored during a locker room remodel in 2002 under the supervision of the 49ers, who had shared the ballpark with the football team since 1971. Mariucci, who was the head coach of the 49ers from 1997 to 2002, was then offered the Mays locker.

“The Black baseball experience has always been about more than just what is found on the scorecard,” said Hall of Fame curator RJ Lara. “This locker is emblematic of the lasting relationships that are forged between budding stars and veterans as they pass the torch from one generation of Black ballplayers to the next.

“Just as Willie Mays served as a cornerstone of baseball for over 70 years, the Mays/Bonds locker will serve as a cornerstone of the Black baseball exhibit for decades to come.”

Mariucci, 68, who has appeared as an analyst on the NFL Network for two decades, was an NFL coach for nine years, spending six with the 49ers and three with the Detroit Lions while compiling a career record of 72 wins and 67 losses. He led the 49ers to four playoff appearances including a trip to the NFC Championship Game in 1997.

“When the Giants moved, they picked up and left, so we, the 49ers, took over their locker room,” said Mariucci in a telephone interview from his home in Northern California. “Our locker rooms were kind of adjacent to each other. It was an old stadium, and our locker room was very small, so they blew out a wall and we took over the Giants locker room and that made it just football.

“In the process of the renovation, all the lockers were in there still. And the guy that was in charge of the stadium, he said, ‘Hey, Coach, we're just getting rid of all this stuff. Would you like to have this locker, Willie Mays’ locker?’ And I said, ‘Of course I would.’”

The locker, after being sent to the Mariucci home, has been in the family garage for more than 20 years.

“And it was awesome. It used up a whole garage space. I walked by it every time I parked my car. But my wife was asking, ‘What are we going to do with that thing?’” Mariucci said. “There were a lot of people that were interested in buying it, but there was no way I was going to sell it. I didn't feel right about that. Then I thought, ‘You know what? It would even be better off in Cooperstown.’ So, then I decided to donate it to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

“I have a colleague at the NFL Network, Chris Rose, who is friends with Hall of Fame President Josh Rawitch. I said, ‘Hey, call your buddy up and see if they would be interested in having this.’ It just made all kinds of sense. As much as I loved owning it, I just felt that it was more beneficial for other people to enjoy. It became a very easy decision. I'm proud that it's there. He’s one of the greatest players of any sport of all time, so it needs to be there.”

Mariucci’s connection with Mays goes back to his childhood in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

“Iron Mountain is 500 miles north of Detroit, but I was not a Detroit Tigers fan even though I was in Michigan. I saw Willie Mays on the cover of Sports Illustrated and I started reading about this guy. I might have been 12 years old at the time,” Mariucci recalled. “And for some odd reason I became a Willie Mays and San Francisco Giants fan. And I would watch them and Willie McCovey and Juan Marichal and all these guys from Michigan when I was a kid growing up. But I was just obsessed with Willie Mays. I literally grew up a Willie Mays fan as a kid.”

While Mariucci made his name in football, first as a college quarterback then as a successful coach, his relationship to baseball is limited to youthful pursuits. One famous story involved friend Tom Izzo, the longtime men’s basketball coach at Michigan State, and was recalled in a 2005 issue of Sports Illustrated.

“We played Little League against each other," Mariucci said. “Once I was on third, showing off, and he was catcher, and he fired the ball to the third baseman and got (me) out. I hated his guts.”

The two competed against each other until they both attended Iron Mountain High School and Northern Michigan University together, ultimately living together for seven years.

Mariucci later talked of spending time with Mays at a bocce ball tournament the onetime football coach has run in the Bay area for 26 years. During the interview, he said he was glancing at a photo on his office wall the two took standing together at the tourney.

“I just idolized that guy,” Mariucci said. “I'm looking at it now and he’s got such big, strong hands. He was just something else. He could do everything.”

Two days after Mays’ passing, in a follow-up conversation, Mariucci said: “As a kid from Iron Mountain, Mich., my boyhood heroes and who I followed were Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers and Willie Mays. That's what got me started and interested in sports. I've been a Willie Mays fan for 60 years, essentially.

“I hope that kids that aspire to be an athlete, whatever the sport, I hope they have a hero, a mentor, a role model, like Willie Mays. Somebody that they really admire and look up to. That right person that can help motivate them to be the best they can be. Willie Mays was that guy for me.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

RELATED STORIES

Willie Mays redefined what was possible on diamond

Bats from Black baseball stars tell incredible stories in Cooperstown

Gibson's powerful swing through Puerto Rico showcased in The Souls of the Game

Museum’s new The Souls of the Game exhibit debuts to rave reviews

RELATED STORIES

Willie Mays redefined what was possible on diamond

Bats from Black baseball stars tell incredible stories in Cooperstown

Gibson's powerful swing through Puerto Rico showcased in The Souls of the Game