- Home

- Our Stories

- Willie Mays redefined what was possible on diamond

Willie Mays redefined what was possible on diamond

The debate over baseball’s greatest player likely will never be settled, but one truth will always remain: Any discussion invariably includes Willie Howard Mays.

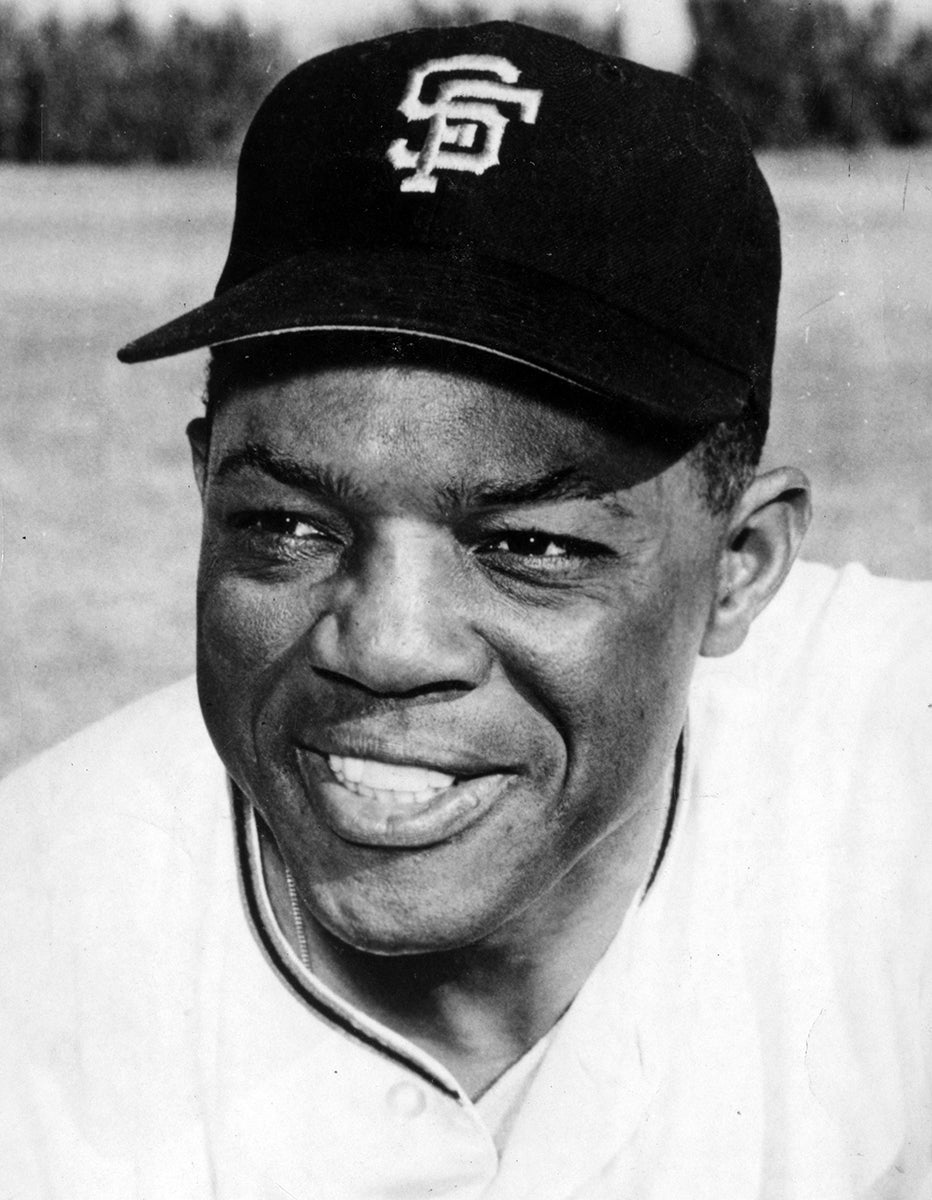

Mays passed away Tuesday, June 18, at the age of 93 – leaving behind a legacy of greatness. Few ever witnessed a better all-around player, and his election to the Hall of Fame in 1979 was the coronation of a man who was baseball for millions of fans of the postwar generation.

"Willie Mays’ passion for the game and incredible talent made him the embodiment of baseball for millions of fans and one of the most beloved players in history,” said Jane Forbes Clark, Chairman of the Board of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. “More than a half century after his playing days, he remained an American treasure and a baseball icon synonymous with love of the game. His ever-present smile and joyous presence radiated throughout Cooperstown, and we will forever cherish his legacy. For teammates, opponents and friends, Willie Mays exemplified excellence.”

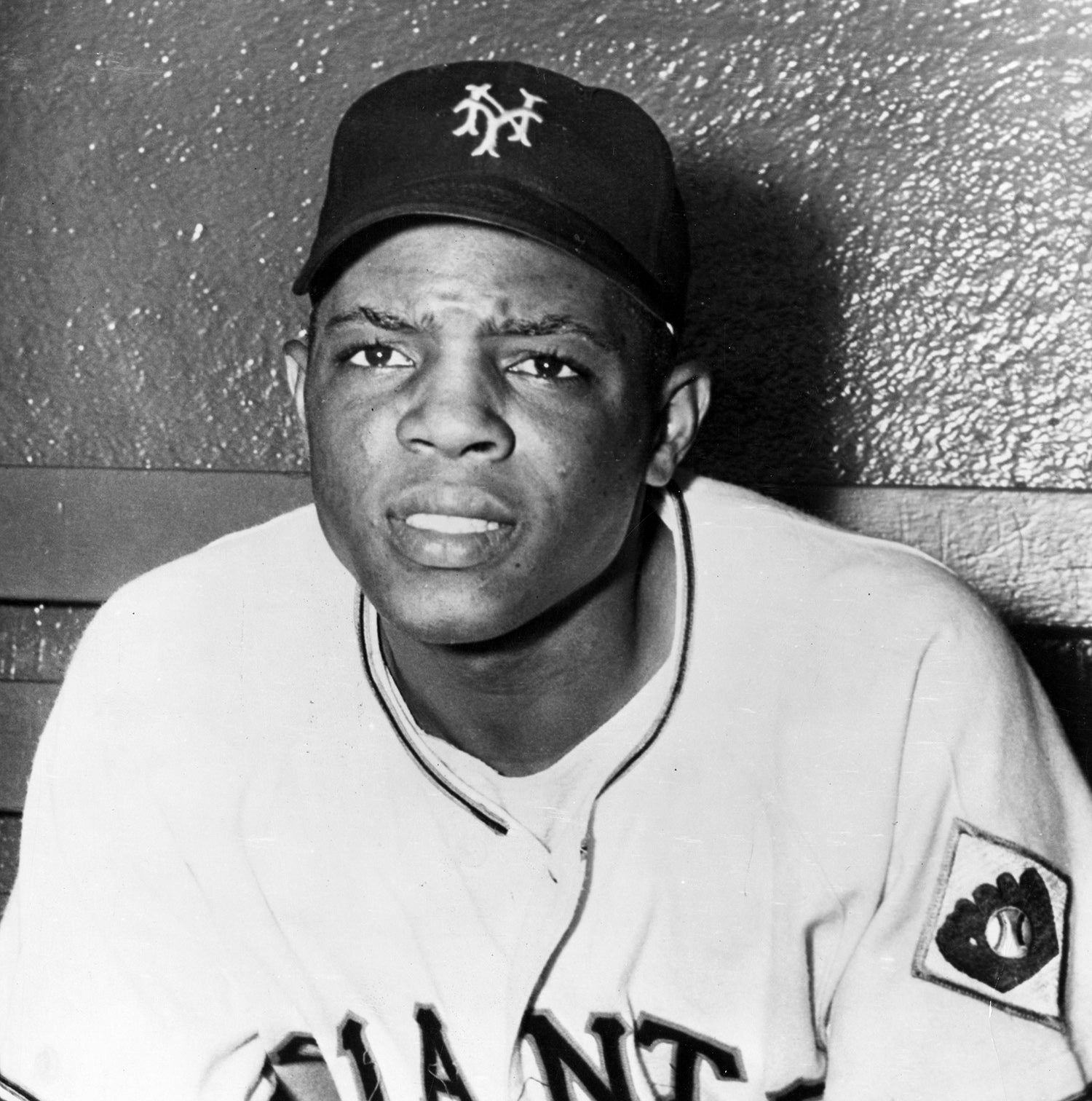

Born May 6, 1931 in Westfield, Ala., the man who would become The Say Hey Kid took New York by storm when he debuted with the Giants in 1951.

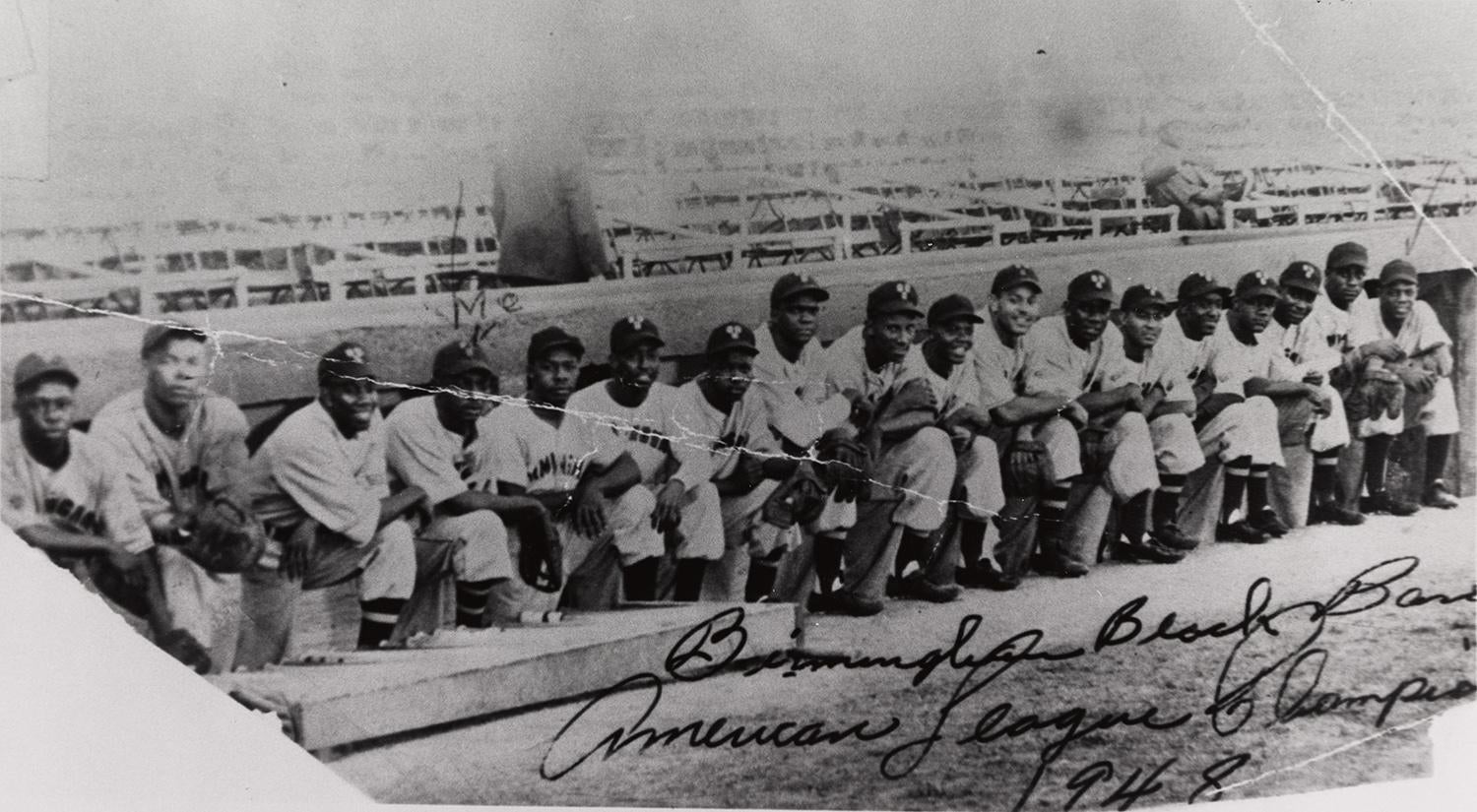

The son of a track star mother and semi-pro ballplayer father, Mays showcased his athletic talent at a young age. Playing alongside his father, Mays competed in semi-pro baseball and played for a Negro League minor league team before the age of 16 before debuting for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League in 1948.

He eventually signed with the New York Giants for $250 per month and a $4,000 signing bonus. Fighting racism, he quickly moved up to the top minor league club and developed a reputation for his style of play.

Showing a rarely-before-seen combination of speed, power and flair, Mays powered the Giants’ improbable run to the pennant during his rookie season before missing most of the next two seasons while serving in the Army.

“If somebody came up and hit .450, stole 100 bases and performed a miracle in the field every day I’d still look you in the eye and say Willie was better,” Hall of Fame manager Leo Durocher once said. “He could do the five things you have to do to be a superstar: Hit, hit with power, run, throw and field.

“And he had that other magic ingredient that turns a superstar into a super superstar. He lit up the room when he came in. He was a joy to be around.”

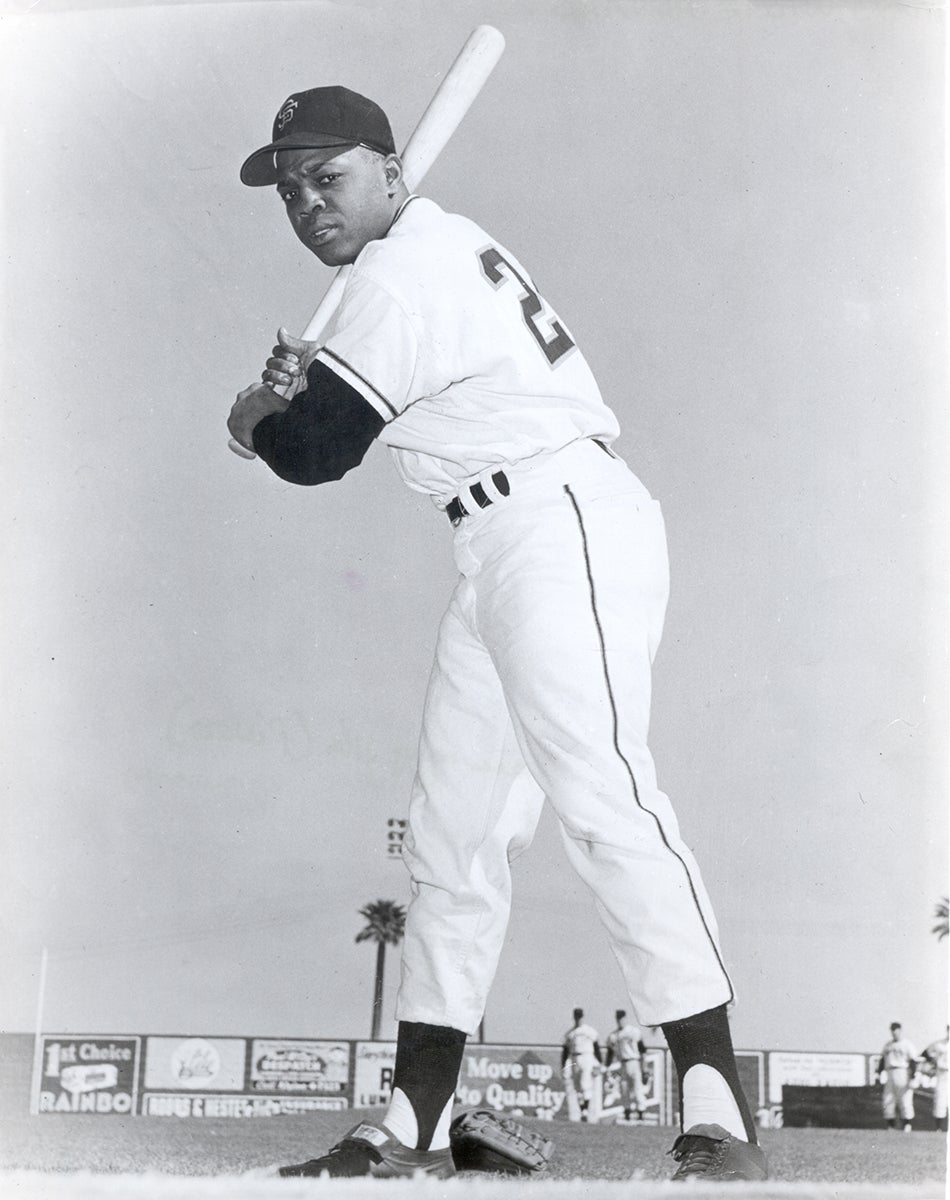

Back on the field in 1954, Mays began a string of seasons that saw him evolve into the game’s most versatile performer. That season, Mays led the National League with a .345 batting average en route to league Most Valuable Player honors while helping the Giants win another pennant.

In the World Series, Mays authored one of baseball’s signature moments with an over-the-shoulder catch on a ball hit by the Indians’ Vic Wertz to the Polo Grounds’ cavernous center field, preserving a 2-2 tie in a Game 1 contest the Giants would go on to win in extra innings.

New York swept the Indians in four games, marking Mays’ only World Series title.

For the next decade-plus, Mays remained a five-tool threat who seemingly could do anything on the diamond. His consistent power at the plate resulted in six 40-home run seasons, and his speed on the bases produced four stolen base titles.

Defensively, Mays won 12 Gold Glove Awards in center field – and likely would have had more had the award existed during the early part of his career.

Off the field, Mays’ infectious enthusiasm for the game won the hearts of a generation of fans who were the first to experience baseball through television. First in New York City and later in San Francisco, Mays embodied the youthful zest for a children’s game that had become a nation’s pastime.

Mays won his second Most Valuable Player Award in 1965, hitting a career-best 52 home runs. A regular in center for the Giants through his age-40 season, Mays was traded to the Mets midway through the 1972 campaign – and helped New York capture the NL pennant as a part-timer in 1973.

When he retired following the ‘73 season, Mays had accumulated 660 home runs, 3,293 hits and 24 All-Star Game selections.

Mays was the first player in history with at least 500 home runs, 3,000 hits, 2,000 runs scored and 300 stolen bases.

“Mays,” said Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, “is the greatest baseball player that ever lived.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum