- Home

- Our Stories

- Tracks of Cardinals heroes

Tracks of Cardinals heroes

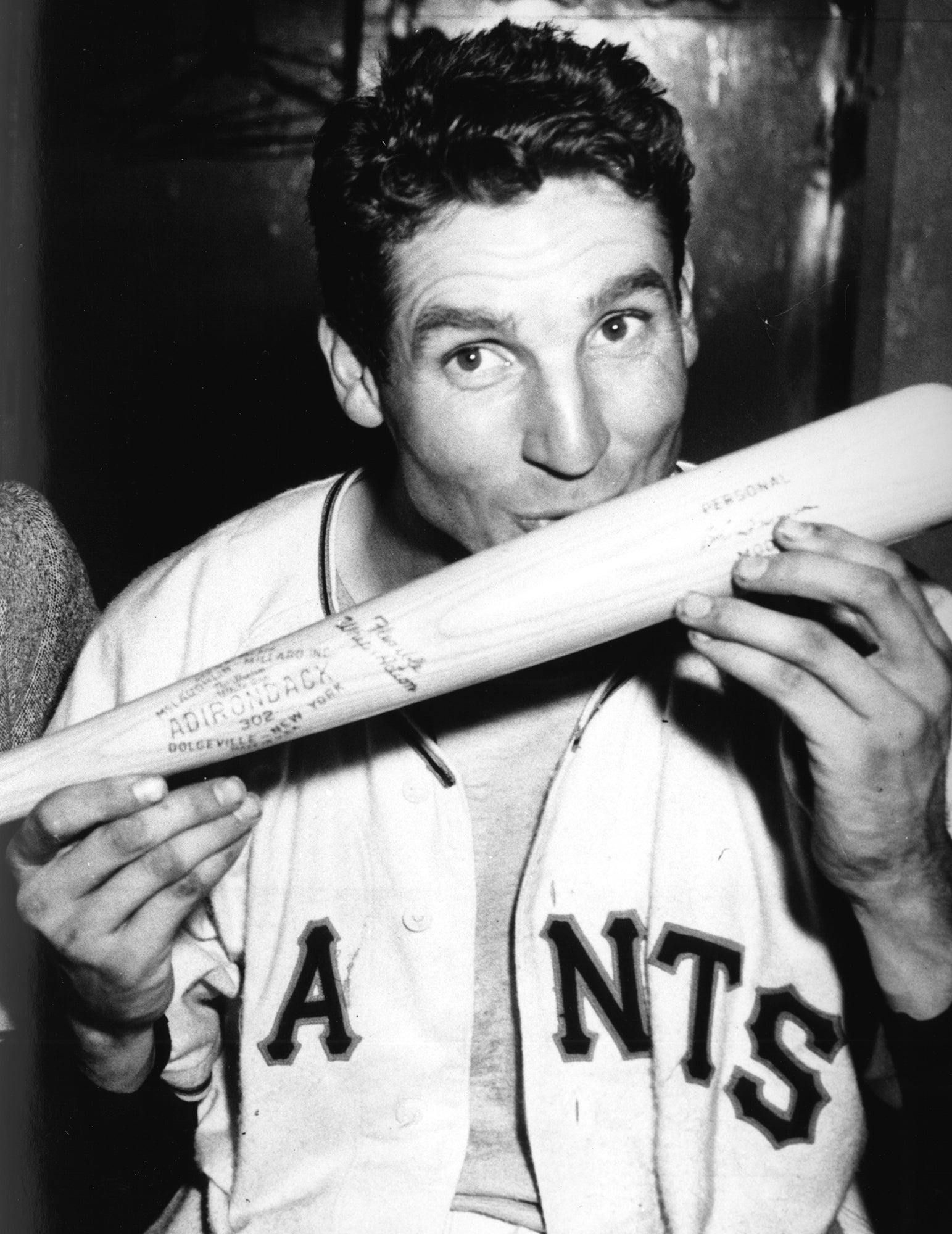

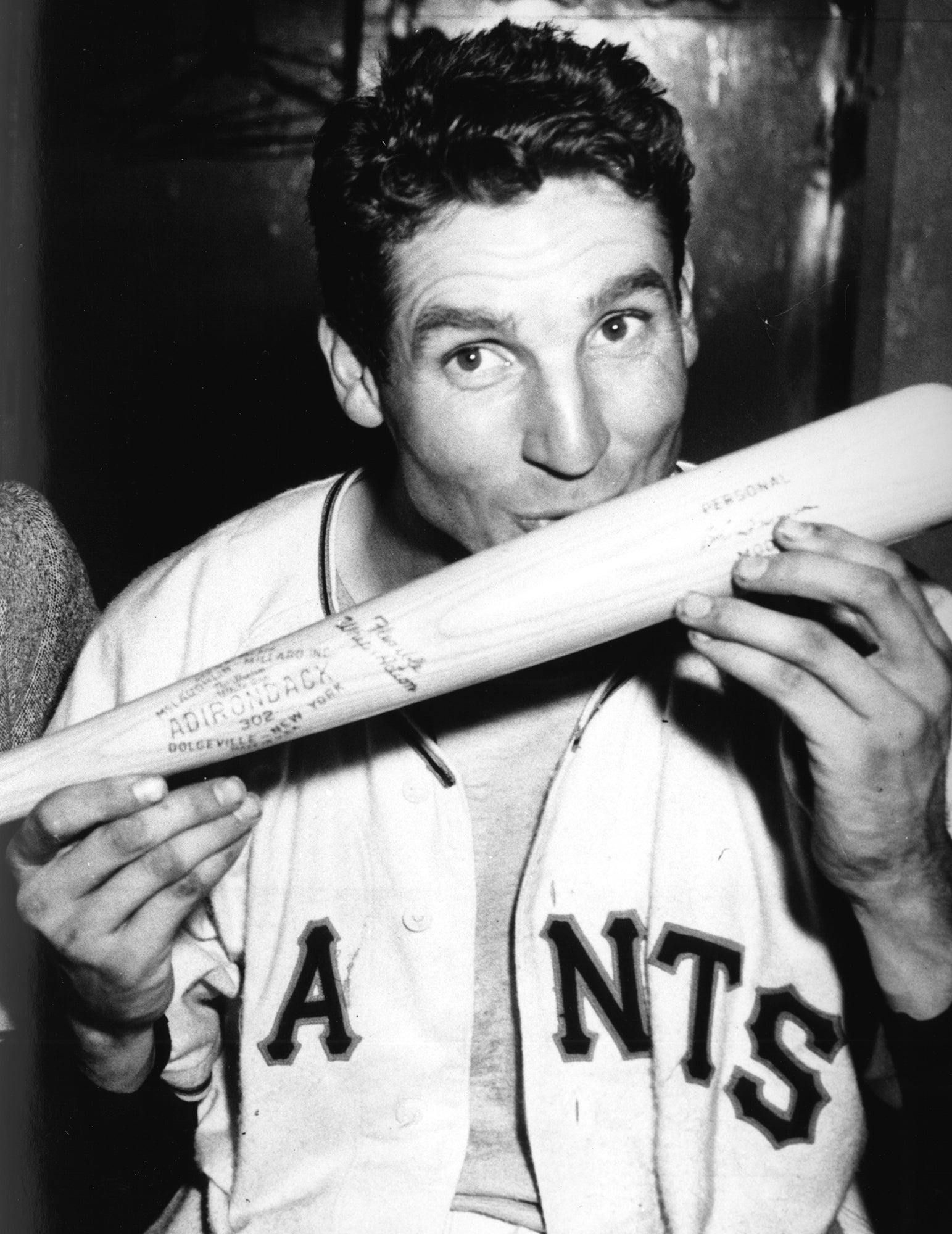

On July 11, 1911, Cardinals player-manager Roger Bresnahan sent the following telegram to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

Every car on train demolished except our two Pullmans in rear.

All my men safe. We called off game with Boston because we lost our baggage and had no uniforms to play in.

R. BRESNAHAN

The story of the train wreck referenced in that telegram – involving the future Hall of Famer and his St. Louis teammates – is a remarkable tale of tragedy, fate and heroism ... and it all began one night earlier.

Before the days of practical air travel, baseball clubs made trips between Washington D.C., Philadelphia, Boston, and New York, on board the “Federal Express” of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad line. On the evening of July 10, 1911, after completing a four-game series against the Phillies, Bresnahan, his Cardinals players, the club treasurer, and a pair of St. Louis sportswriters boarded that very train at Philadelphia’s Broad Street Station for the 10-hour ride to Boston.

Originally, the ballplayers occupied a pair of Pullman sleepers located near the front of the train, close behind the 10-wheel locomotive and a U.S. Fishery coach. The position wasn’t ideal. Amid the sweltering heat that saw the mercury rise to 100 degrees earlier that day, it was nearly impossible to sleep with the car windows closed. But opening the windows only made matters worse, letting in the unpleasantness of engine cinders and the stench of baby trout.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Well past midnight, after taking the Jersey City ferry, the cars were repositioned, with the Cardinals’ Pullmans moving to the very rear of the 10-car arrangement, while a day car and four other sleepers moved closer to the front. Contemporary sources differ on why the cars were rearranged. Some state that the move was in response to Bresnahan complaining about their position, while others claim that a simple mix-up occurred when the cars were coupled back together. Whatever the reason, the alteration proved lucky for the ballplayers but deadly for more than a dozen others.

At 3:32 in the morning of July 11, the Federal Express roared through West Bridegport, Conn., barreling through a crossover at an estimated 60 miles per hour, four times the regulation speed called for at the switch. The locomotive failed to negotiate the curve, jumped the tracks and plunged off the embankment into the street below. A frightful procession of derailed cars followed the mighty engine for some 400 feet as it plowed forward, demolishing telegraph and trolley poles, the girder of a steel bridge and everything else in its relentless path.

The engine had been reduced to a mound of twisted metal and glowing coals. As Cardinals pitcher Slim Sallee observed: “The locomotive looked like a tin can that had been placed under a pile driver. Only a cylinder and the cow-catcher remained to tell what had landed on the pavement.” Behind the ruins of the engine lay a melee of crushed cars haphazardly strewn about, their structures mangled into splinters of wood and piles of iron.

Miraculously, the last two cars, the very ones that carried the Cardinals’ entourage, remained on the rails and escaped serious damage, as did the individuals within. The rest of the scene, however, was one of calamitous destruction and horrifying injuries.

Once Bresnahan realized what had taken place and found that none of his players were seriously injured, the St. Louis manager led his players in rescue attempts. As detailed the next day in the Washington Herald, the Cardinals “hustled out without taking time to change their pajamas for more formal attire. They grabbed their shoes and slid down the embankment without asking instructions from anybody. Bresnahan shouted orders above the chorus of cries and groans that came from the battered cars, and the ballplayers attacked the debris with tremendous energy. ... From the ruins of the day coach, they removed fifteen or twenty men, women, and children who were badly hurt.”

Center fielder Rebel Oakes described the harrowing sight: “The cars that had fallen to the street were piled up like a monster kindling pile. Men, women, and children were sticking out of the debris. Among the passengers was a man who was returning from the funeral of his sister. He was accompanied by his wife and two children. Only himself and one of the children escaped. It was pitiful to hear him crying aloud for his wife and child as he dashed about the wreck.”

Rookie Otto McIvor recalled that, “after taking a survey of the scene ... I pointed to signs that someone had painted on the walls of the viaduct and asked Captain Bresnahan, ‘What do you know about that?’ The signs were as follows: ‘Watch and Pray,’ ‘Obey the Lord,’ and ‘Prepare to Meet Thy God.’ I thought it something to ponder over, that they had painted at just the place our fellow passengers’ lives were to be crushed out.”

Though police and volunteers soon arrived, the ballplayers continued their valiant efforts for nearly three hours before eventually taking leave of the scene to catch another train for Boston. When they arrived shortly after noon, the exhausted men collapsed in their hotel rooms. The baggage car having been destroyed, some had nothing more than the clothes on their back. Meanwhile, Boston granted Bresnahan’s request to postpone the day’s game and reschedule it as a doubleheader the following day.

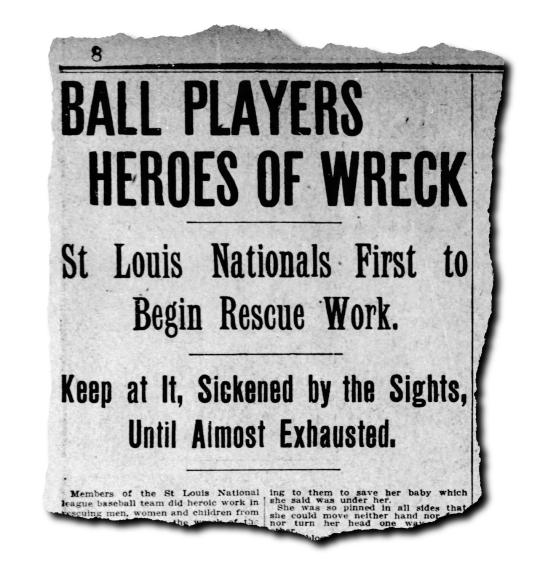

The news of the disaster spread quickly, most every story noting the important and selfless work of the young athletes. The Boston Globe, for example, reported that “members of the St. Louis National League baseball team did heroic work in rescuing men, women, and children from the debris caused by the wreck of the Federal Express at Bridgeport yesterday morning. The ball players regard their own escape from death as miraculous and there is no doubt but what many others who escaped owe their lives to the rapid thought and quick action of these same men.”

All told, of the 150 passengers aboard the Federal Express, 14 lost their lives and another 47 were seriously injured. Just why the train sped recklessly as it approached the Bridgeport Station remains a mystery to this day, the engineer unable to shed light on the cause as he perished in the accident. But the lucky circumstances that spared the lives of the Cardinals players allowed them to perform gallant duties in the wee hours of that fateful morning.

On July 12, Boston hosted the Cardinals for the hastily arranged double-header. Despite the home team’s dismal record of 18-56 and a stifling heat wave that gripped the Northeast, nearly 4,000 fans passed through the turnstiles at Boston’s South End Grounds. There the local rooters saw the St. Louisans take the field, but not in their usual visiting team uniforms of gray with red highlights. Those outfits, along with most of the club’s equipment, had been lost in the smoldering ruins of the Federal Express.

Instead, the Cardinals strode onto the diamond wearing Boston’s dark blue road duds, each bearing a white, old-English “B” on their left sleeves where the red “STL” should have been. And when Bresnahan stepped to the plate in the top of the first (after his teammates had already pounded out four runs), the crowd showed their appreciation for the heroic manager by giving him a rousing and heartfelt cheer.

Tom Shieber is the senior curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

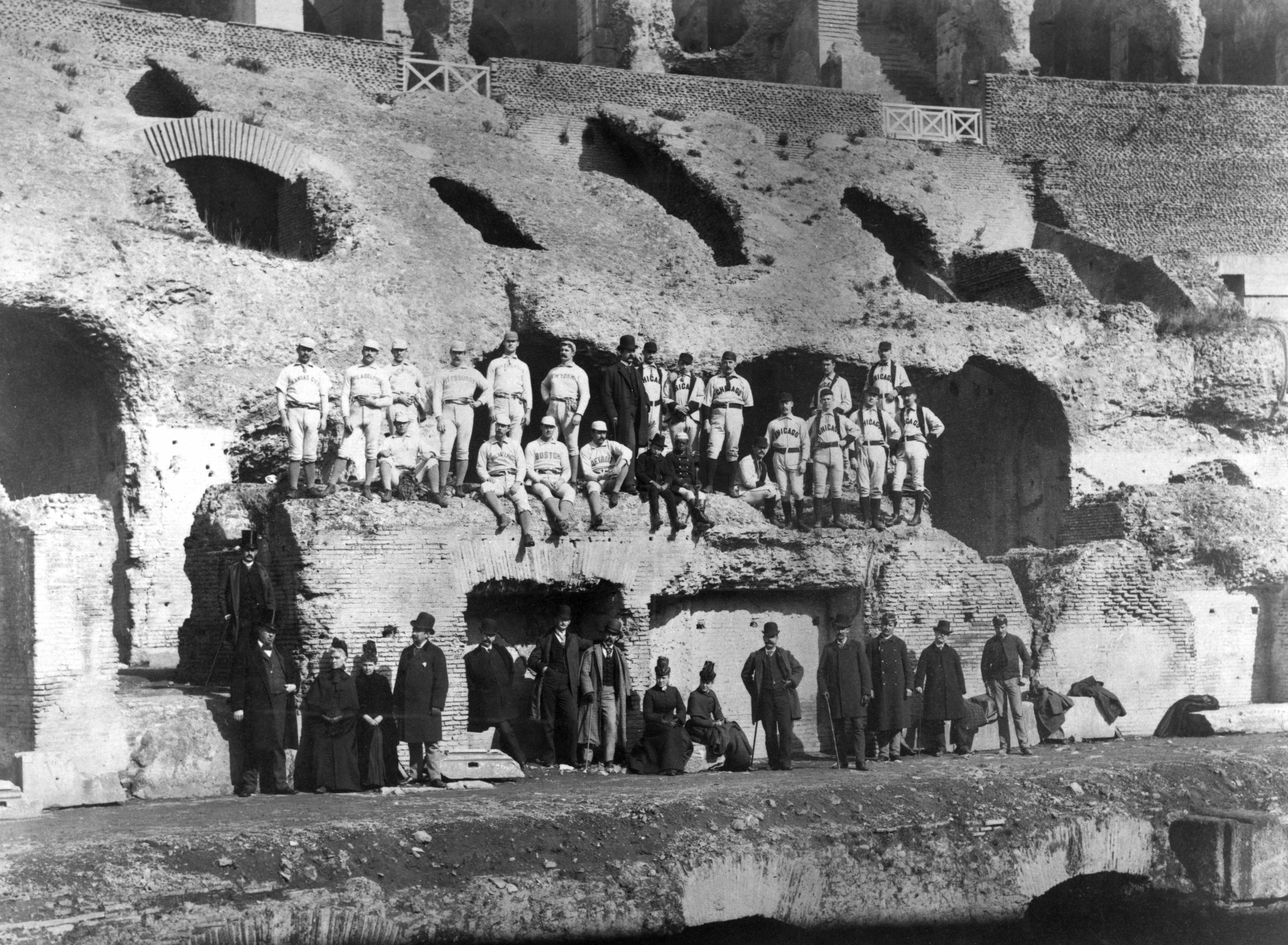

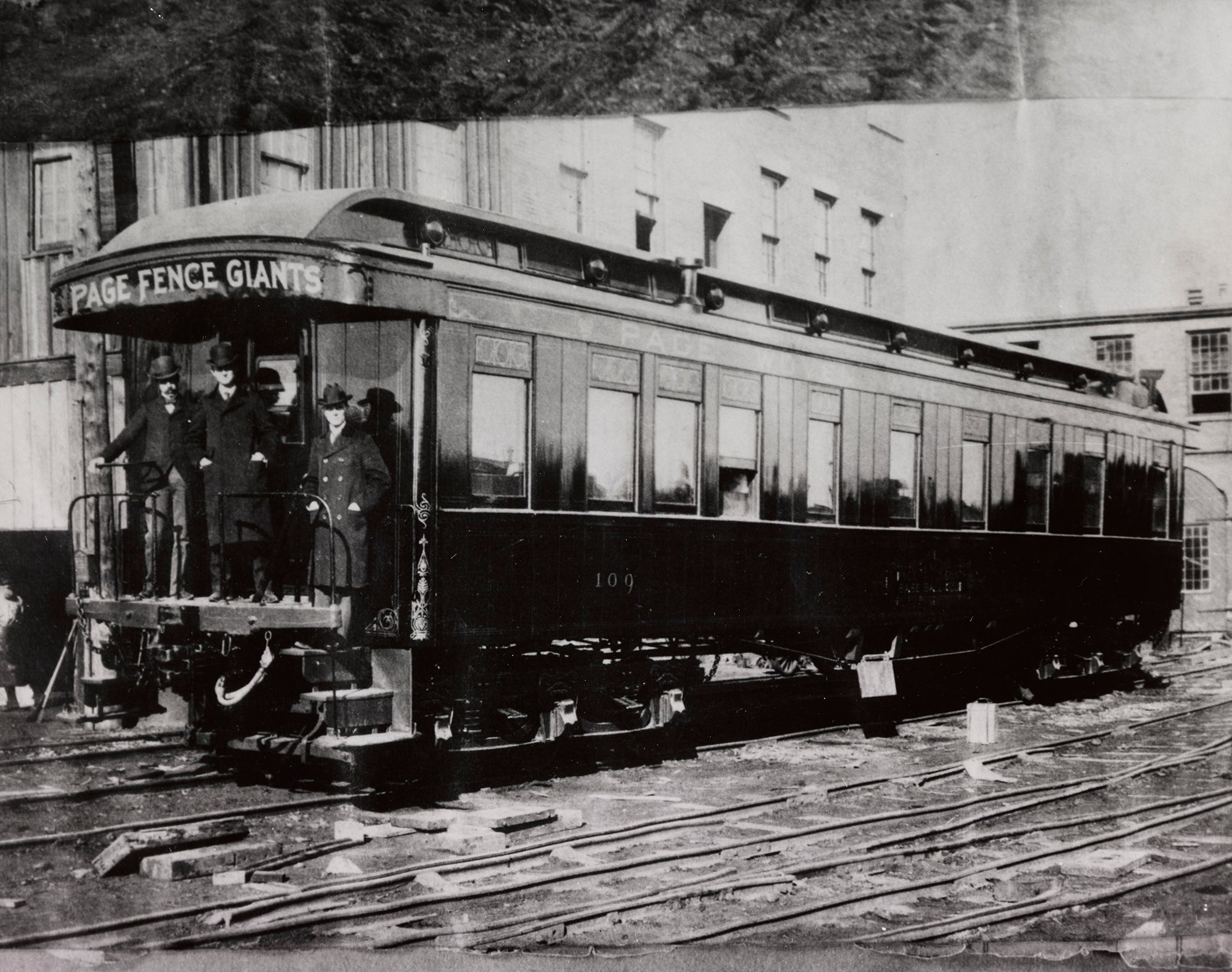

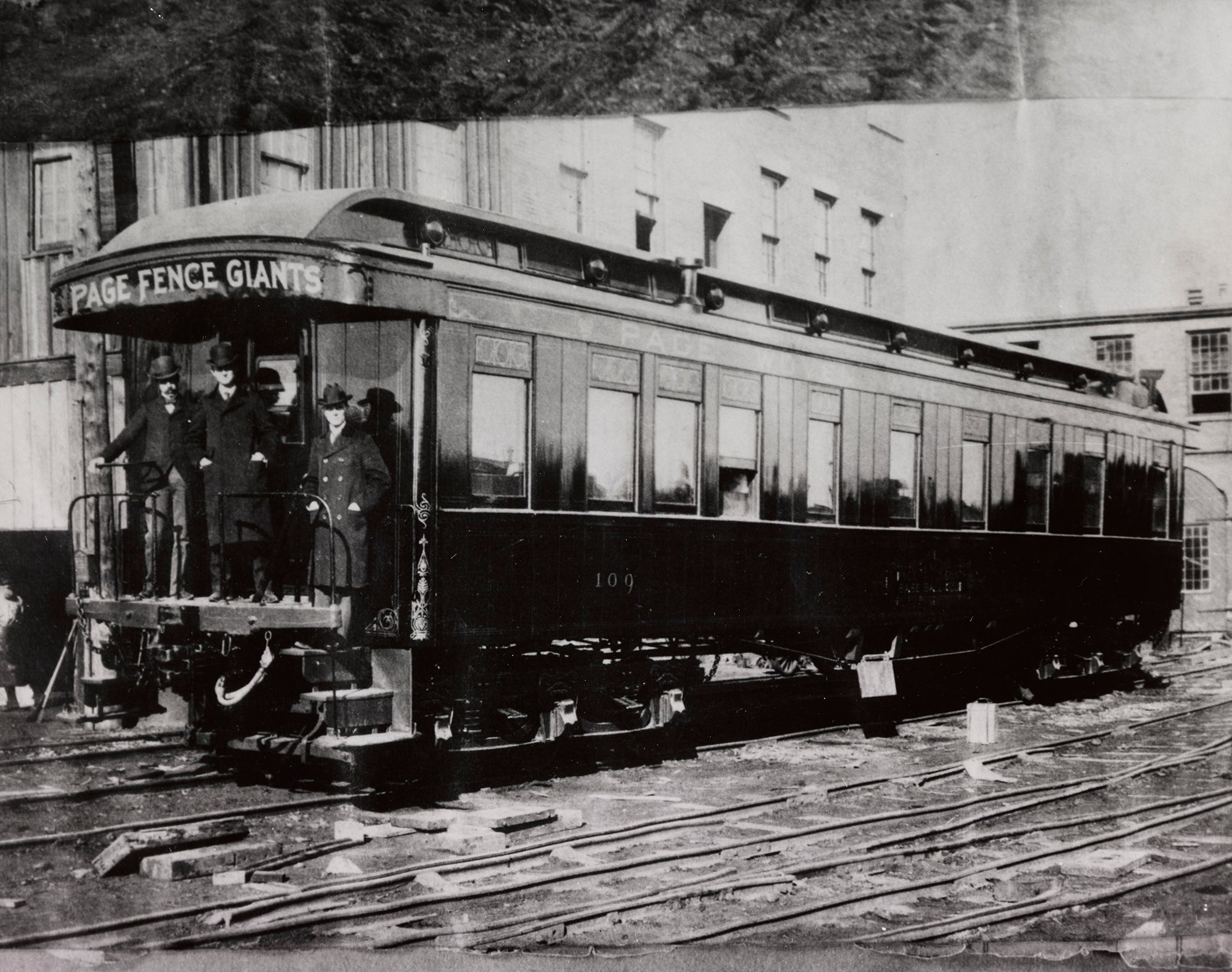

Advent of regional rail service made baseball possible

Sound on Paper

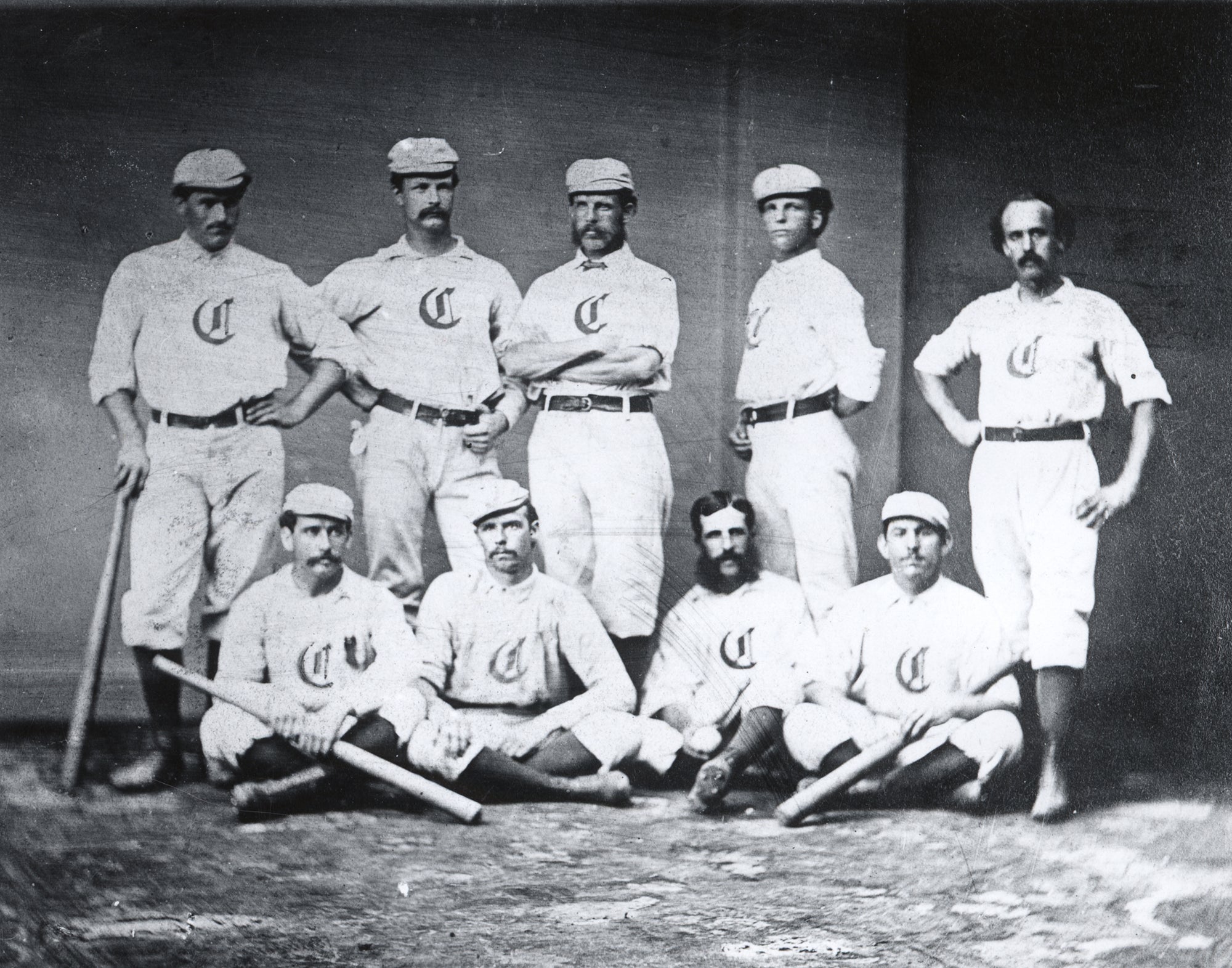

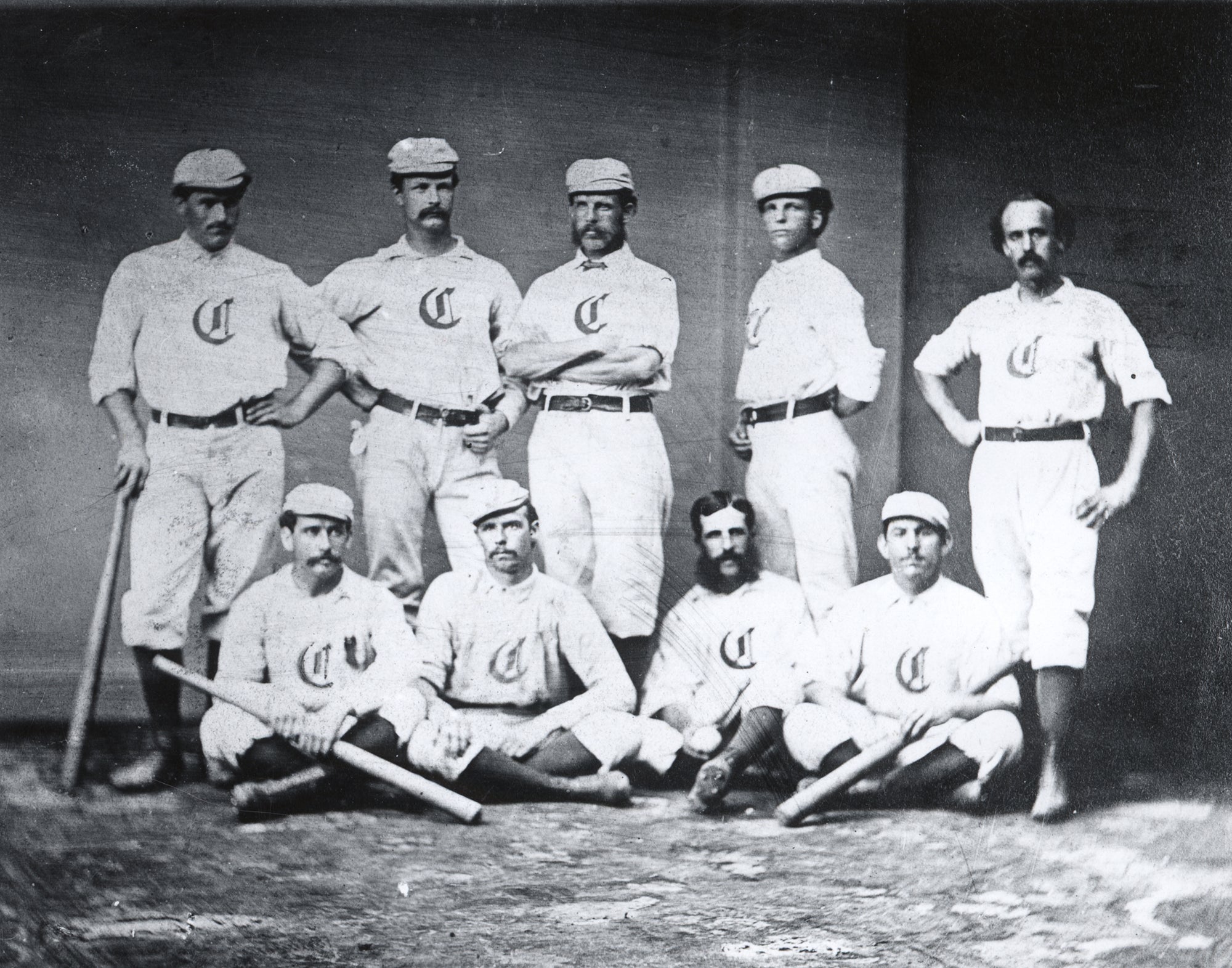

Trips by the 1869 Cincinnati team made the game famous

Advent of regional rail service made baseball possible

Sound on Paper