- Home

- Our Stories

- Trips by the 1869 Cincinnati team made the game famous

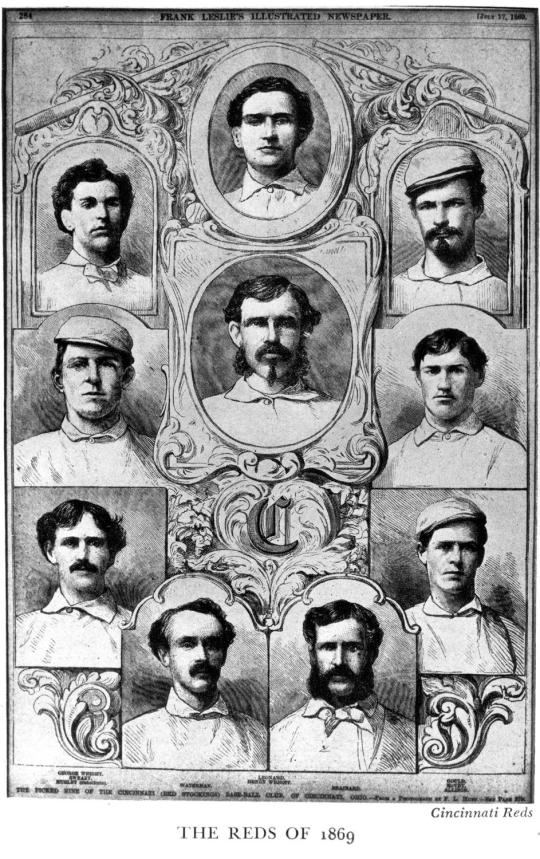

Trips by the 1869 Cincinnati team made the game famous

The greatest road trip in baseball history was arguably the one that was the most ambitious: The 20-game, June-long, 1,821-mile trip by the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings.

Three months later, they capped a 57-0 inaugural season with a 4,764-mile trip to San Francisco and back aboard the Transcontinental Railroad, which was completed only the previous May with the pounding of the Golden Spike at Promontory, Utah.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

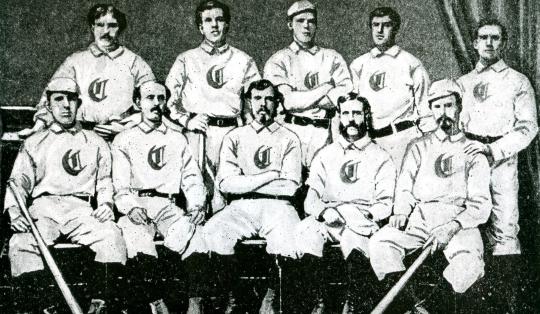

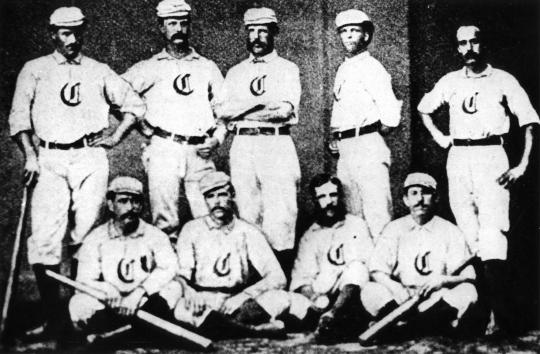

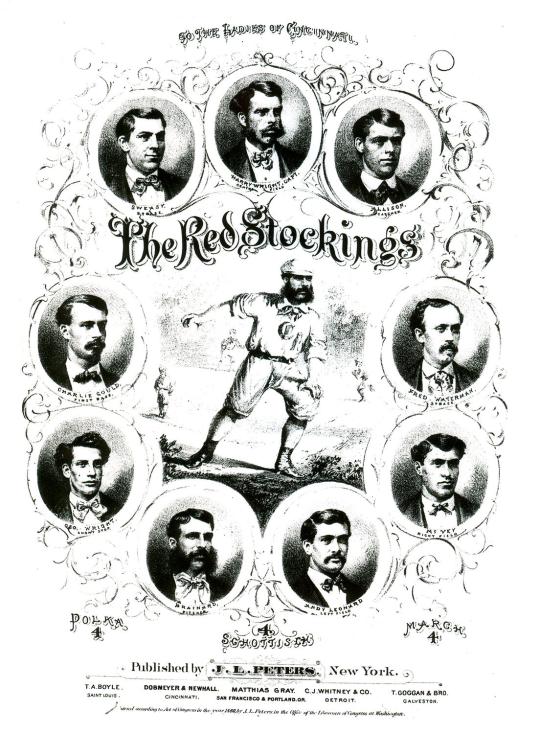

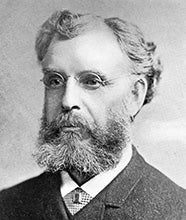

Two of those Red Stockings are in the National Baseball Hall of Fame: Shortstop George Wright, inducted in 1937, and his brother, center fielder/manager Harry, inducted in 1953. Harry is known as the “Father of Professional Baseball,” and his brother as baseball’s first superstar.

The Wrights led the team to both coasts, foreshadowing baseball’s expansion to the West Coast 90 years later. Both of the Red Stockings’ trips – East and West – turned out to be masterworks of planning, although the former was incredibly less well-“financed” than the latter. Both trips were full of all sorts of challenges along the way (the Red Stockings embraced risk-reward and on-the-go adjustments). Both trips laid a blueprint for what was to come in baseball.

The Red Stockings’ famous road trip began on May 31 at Little Miami Railroad Depot, today the site of Sawyer Point, an Ohio River park three-quarters of a mile east of Cincinnati’s Great American Ball Park.

The Red Stockings’ 32-day road trip was more like a rock ‘n roll tour than a baseball trip. Huge crowds turned out to see the handsome young men in their crimson hose and white-knicker uniforms in Cleveland, Buffalo, Rochester, Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C., where the Red Stockings received an audience with President Ulysses S. Grant.

They won all 20 games on the road trip, and every game thereafter, playing before 200,000 fans, eating lobster in Boston and Dungeness crab in San Francisco, traveling 6,585 miles by steamboat, stagecoach and train on just those two trips alone.

But things didn’t start out so promising.

The day before the Eastern trip began, a game scheduled at the home park Union Grounds to raise money for the trip had been rained out. A shareholder in the club, Will Noble, had to borrow $300 ($5,575 in today’s dollars) from his wife to get the trip started. It bought the team tickets as far as Boston. But the 10 players and two club executives needed to eat and occasionally sleep in a real bed. That same night, club president Aaron Champion visited the players in their rooms at the Gibson House to ensure they weren’t drinking. It didn’t work. The next morning, Champion found that “some of the members of the nine, forgetful of (their temperance) pledges had touched the rosy too freely.”

The Red Stockings, some grumpier than others, along with beat writer Harry Millar of the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper, boarded the train. Things didn’t improve. It was pouring in Yellow Springs, located just outside of Dayton, Ohio. The boys headed northeast for Mansfield in the smoke-filled train.

Millar: “The boys, weary after riding so many miles, with the dampness of the misty atmosphere coming in the open windows, and at intervals almost suffocating, (were) again obliged to turn up coat collars and bind handkerchiefs around the (mouth, nose and) throat to prevent catching a cold.”

Some of the players tried to sleep. George Wright, armed with a long-legged wire spider, walked down the aisle, dropped it gently on the faces of the sleeping. Unsuspectingly, those who were pranked flicked the “spider” away, drawing laughs from Wright and those players who hadn’t yet dozed off.

The Red Stockings were a team full of characters, including a pool shark who was a hypochondriac, a boxer turned right fielder and a second baseman who couldn’t stop partying. Eight of the 10 were young, 18 to 23. Harry was 34, pitcher Asa Brainard 30. All were ballers – ballers at the mercy of Champion and his right-hand man, John Joyce, who had to keep the trip financially afloat despite the rain – even accepting a loan from the beat writer. Champion knew Millar’s family, and knew that Millar’s family had advanced their son a sizeable sum for his expenses.

Champion and Joyce gave Millar a promissory note Millar kept to his dying day: “Received of Harry M. Millar $245 as a loan to the Cincinnati Baseball Club, to (be) repaid out of New York receipts of gate money… Amount of loan guaranteed by John P. Joyce, A. B. Champion.”

In Rochester, N.Y., the game had barely begun when rain soaked the teams and their eager fans. The Red Stockings broomed off the puddles, spread sawdust in the mud and played on.

When the team arrived for their game in Syracuse, the outfield grass was a foot high and the fence was in a shambles. The Red Stockings had walked into the middle of a pigeon shoot. Harry couldn’t find anybody who remembered scheduling the game, so the team settled for a salt bath at a local spa for 35-cents apiece.

The week that made baseball famous began on Tuesday June 15 and ended on Monday June 21. But first it required a setup. It came on Monday, June 7, when the Red Stockings arrived in Lansingburgh, N.Y., a village on the north end of Troy, on the east shore of the Hudson River, 80 miles from Cooperstown.

It is a direct shot – 175 miles due south down the Hudson – to New York City. Even in those days, one had to take Troy before one could take Manhattan. And the Red Stockings did, 37-31. In Boston they whipped four Massachusetts nines.

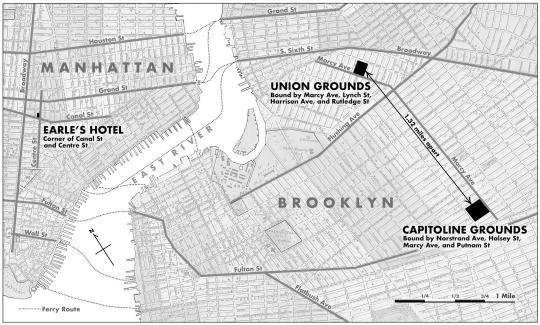

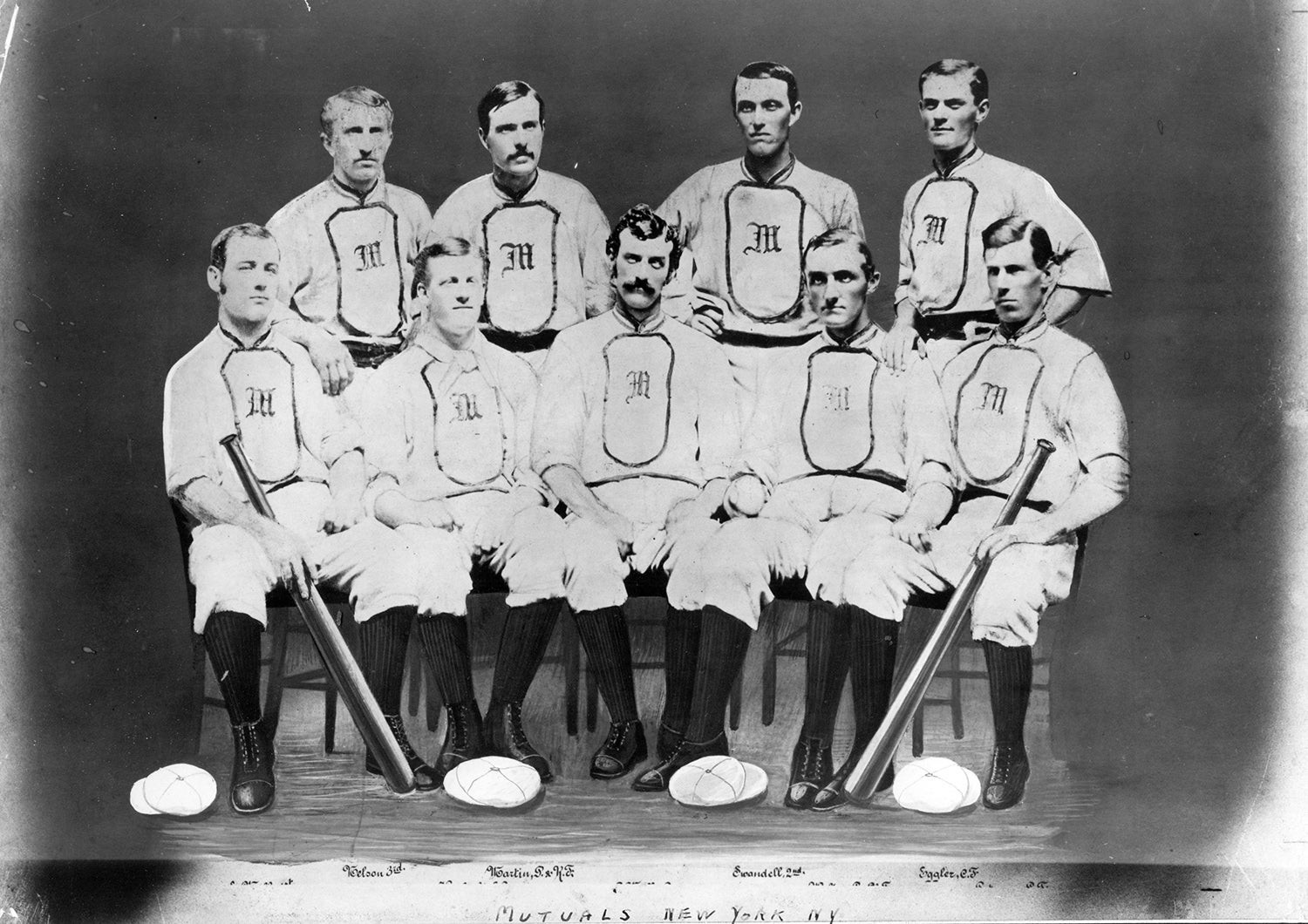

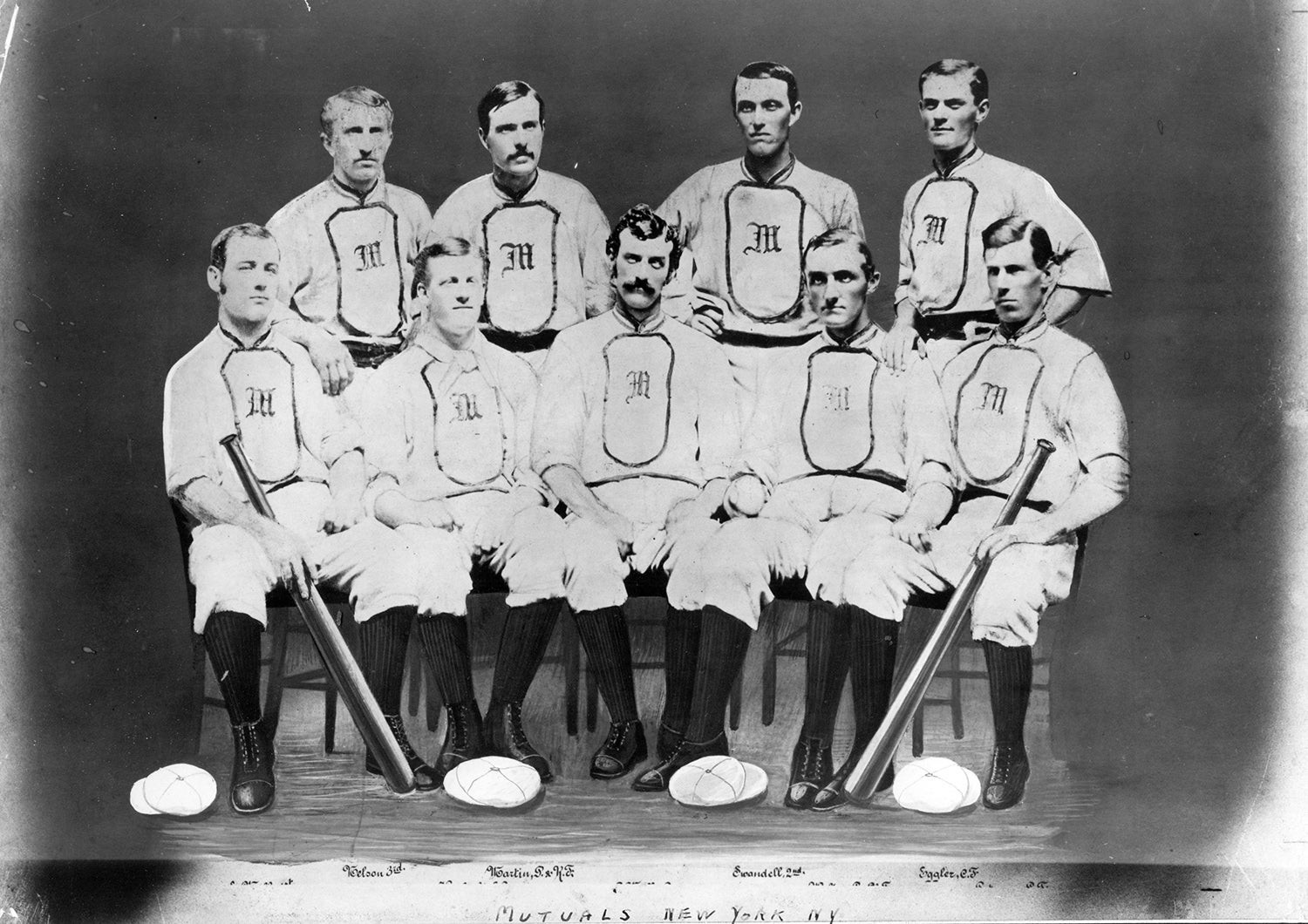

The Red Stockings arrived at Earle’s Hotel in lower Manhattan at 8 o’clock Monday night June 13. At 1:30 p.m. the next day, officials of the New York Mutuals club called upon them, several elegant coaches at the ready, to ferry the impeccably clad Red Stockings across the East River to the Union Grounds in Brooklyn, Greater New York’s most famous ballpark. The crowd was wired, eager to see the youngsters from Cincinnati who had whipped the Haymakers. The spectators roared at the first sight of red, bringing cap-tips from the players. The ensuing 4-2 game – the Red Stockings scored twice in the bottom of the ninth inning – had the crowd on its feet; even the newspapers crowed: “Bully for you boys,” wrote the New York Gazette reporter.

The greatness of the 4-2 game, defensive gem after gem, belying the underhand era in which scores of 40 and 50 runs were common, was immediately proclaimed an instant classic. It brought out a huge crowd for the next-day’s game at the Capitoline Grounds estimated at 12,000 (by far the biggest baseball crowd to date). The Red Stockings walloped the powerful the powerful Brooklyn Atlantics, 32-10, then knocked off the Eckfords 24-5 the next day back at the Union Grounds.

Three victories in three days over the best teams in New York, birthplace of the pastime, with the Red Stockings pocketing a $1,700 share of the bloated gate receipts.

One huge foe awaited, the Philadelphia Athletics, adjudged by everybody as the strongest group of hitters anywhere, one through eight. The dizzying fame of the Cincinnati nine drew the attention of female admirers. As a light rain fell on the eve of the Athletics’ game, a group of young women passed in front of the Red Stockings’ hotel. They lifted their long skirts to avoid the mud in the streets, many revealing a flash of red stockings. The Cincinnatis won the next day, 27-21.

Then home to a raucous parade, eight city blocks long, and a sumptuous banquet at the Gibson House. Club officials pondered what might come next.

A key to the Red Stockings’ decision to travel to the West Coast in September of 1869 was the earnestness of the invitation from W. L. Hatton, the proprietor of San Francisco’s new, enclosed ballpark, the Recreation Grounds, aka “The Rec,” corner of Folsom and 25th. The San Francisco clubs would pay all of the Red Stockings’ expenses and give them half of the gate receipts. Hatton himself traveled to Cincinnati to handle the details of the trip.

On Tuesday afternoon, Sept. 14, the Red Stockings departed for St. Louis, arriving the next morning, played two games, headed west, changing trains in Macon to the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad.

Millar: “The cars zig-zag (making it impossible) to stand erect . . . Not only do they zig-zag, they jump up from the track. . . In one place we counted seven freight cars in a triangular heap, with the locomotive about fifty feet in advance, alongside the track in a swampy hole.”

In Council Bluffs, Mo., a stagecoach awaited, the “whip” (driver) choosing the convivial and graceful George Wright and Cal McVey to ride the platform with him. Millar, Charlie Gould and lone substitute Oak Taylor sat on top with the baggage and the rest of the party climbed inside. What a sight! The champion ball club of America bumping and bouncing toward the next great adventure.

In Omaha, Neb., Harry and the boys boarded a special Pullman “Silver Palace” car on the Union Pacific Railroad. The operator of Cincinnati’s grand Gibson House hotel catered a party in a large, private compartment at the rear of the car that Hatton had reserved. Millar reported everyone in “jubilant spirits,” eating, drinking and carrying on. Millar noted that the team’s quartet of singers – Brainard, third baseman Fred Waterman, left fielder Andy Leonard and the writer himself – had improved considerably since the team’s Eastern tour.

As for the Transcontinental train ride itself, Millar wrote: “It is almost impossible to keep the boys inside of the car (so anxious are they) to get a glimpse of everything attractive or novel.” Sightings of buffalo, antelope and prairie dogs created an uproar and dash for the windows. Harry and some others carried pistols and rifles and – in the custom of the day – took potshots at this menagerie from the train windows. At each stop, the players would hurry outside and toss the ball about to keep their arms in shape, much to the astonishment of the locals, especially the Native Americans and the Chinese.

Darryl Brock, a painstaking researcher, described the scenery the boys would have seen in Utah Territory this way in his bestselling novel, “If I Never Get Back”: “We climbed through the rugged gorges of Echo and Weber Canyons, staring at thrusts of red sandstone towering hundreds of feet above – Devil’s Gate, Devil’s Slide, Witches’ Rock – as we passed along the ledges barely wide enough for the tracks. The Weber River was spanned by a reconstructed bridge. The original had washed away. This one swayed alarmingly as the engineer stopped in midspan so we could look straight down into a chasm where the river flowed between rock walls.”

Once in San Francisco, the Red Stockings routed the opposition. The “Frisco” clubs, however, had one custom the Red Stockings were not familiar with. At the end of the sixth inning, the teams observed a 10-minute intermission, “a dodge to advertise and have the crowd patronize the bar,” Millar wrote.

Away from the ballpark, the Red Stockings enjoyed the sights of the Bay Area. There was no Golden Gate Bridge or Coit Tower, but there was Chinatown and the Cliff House overlooking the Pacific Ocean, where sea lions perched on the rocks.

On the Red Stockings’ final night in San Francisco, they were feted at a splendid banquet, and the next morning headed for home.

The team’s exploits were reported nationally. So familiar were the nation’s ball fans with this team, that in western Illinois when the club stopped for a pre-arranged game with the Quincy Occidentals, they complained about the Red Stockings playing out of position. Harry had wanted to rest the sore hands of catcher Doug Allison. At the end of each inning, the fans called for Harry to put Asa in the pitcher’s box and Allison behind the plate.

Finally, Harry relented and the crowd cheered.

John Erardi, Greg Rhodes and Greg Gajus are the co-authors of the new book, “Baseball Revolutionaries: How the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings Rocked the Country and Made Baseball Famous."

Related Stories

#Shortstops: Cincinnati Pitcher Was Best Batter

#Shortstops: Keeping score 19th century-style

Blockbuster trade sends Morgan to Reds

Larkin’s loyalty made him the Cincinnati kid

#Shortstops: Cincinnati Pitcher Was Best Batter

#Shortstops: Keeping score 19th century-style

Blockbuster trade sends Morgan to Reds