- Home

- Our Stories

- Pre-Negro Leagues stars laid the foundation for integration

Pre-Negro Leagues stars laid the foundation for integration

On April 20, 2013 – a century and two months after his death – a Black baseball pioneer was memorialized with a homecoming ceremony in Cooperstown, the place where he had learned to the play the game during his formative years.

Believed to be the first Black player to suit up with a white professional baseball team, way back in the spring of 1878, John “Bud” Fowler was feted with the naming of a street in his honor next to Doubleday Field. Additionally, a plaque denoting his trailblazing achievements was affixed to the brick wall near the ballpark’s entrance, just down the block from the Baseball Hall of Fame. Fowler became a Hall of Famer as part of the Class of 2022.

A man nearly forgotten by history finally had been remembered, fittingly during the same week as Major League Baseball’s annual celebration of Jackie Robinson’s historic debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Robinson’s courage in breaking the 20th century color barrier is celebrated every year by MLB, as National and American League players all wear Jackie’s No. 42 during designated games in homage to his pioneering moment.

But Robinson’s monumental feat would not have been possible without the paths blazed by determined men like Fowler. Long before Branch Rickey’s “Great Experiment,” and even before the formation of the Negro National League in 1920, Black baseball flourished against daunting, racist odds.

The first documented game between Black teams was played in 1859 – four years before President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation ending slavery and six years before the conclusion of the Civil War. In the ensuing decades, players such as Fowler, Sol White, Frank Grant, Moses Fleetwood Walker and Rube Foster would take a bat to bigotry.

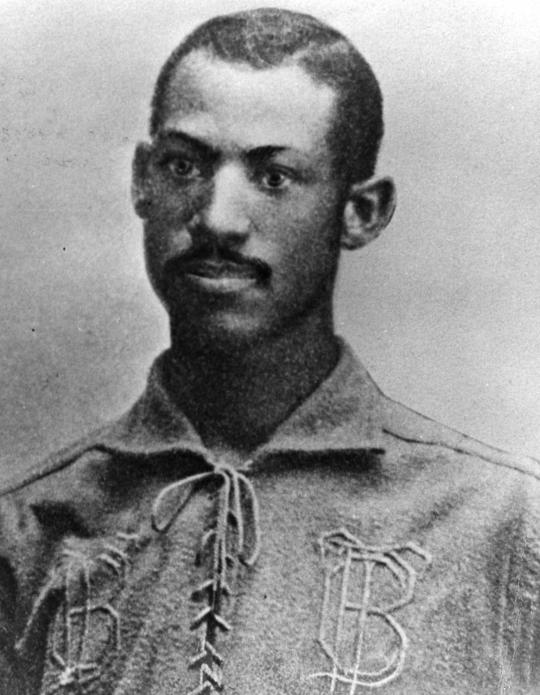

Moses Fleetwood Walker played for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association in 1884. He was the one of the last openly Black players in the segregated major leagues until Jackie Robinson debuted with the Montreal Royals in 1946. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“The history of pre-Negro League baseball is lesser-known, but no less significant,’’ said Dr. James Brunson, a noted Black baseball scholar who has authored several seminal books on the subject. “Without the perseverance of numerous 19th century and early 20th century African-American players, managers and businessmen, the integration of baseball and America for that matter would have been delayed years, if not decades.”

Fowler clearly was at the forefront of desegregation. A man of mystery – and many hats – his legacy includes not only his achievements as a pioneering player, but also as a flamboyant organizer, entrepreneur and marketer of Black teams.

Born John W. Jackson in Fort Plain, N.Y., 25 miles northeast of Cooperstown, it is not known why he changed his name, though, some historians surmise it was because he didn’t want his parents to stop him from pursuing a career in baseball at a time when there weren’t any prominent Black pro teams. His father was a barber – a profession that gave the family middle-class status – and he taught Bud those skills in hopes he would follow in his footsteps. Throughout his life, Fowler would make money on the side providing shaves and haircuts, but his main livelihood would come from baseball, a game he fell in love with in the 1860s after his family moved to Cooperstown.

A white amateur all-star team in Chelsea, Mass., brought him on as a pitcher when he was 20, and on April 24, 1878, he tossed a three-hitter in a 2-1 exhibition game victory against Boston, the reigning National League champs. Within weeks of that sterling performance, Fowler signed a professional contract with the Lynn, Mass., club in the International Association, one of the first two loosely defined minor leagues. That history-making, color-line breaking moment would mark the beginning of an odyssey that saw him play for 18 teams in 13 seasons, including one calendar year when he suited up for four-to-five different teams.

His gypsy career had nothing to do with his talent – he was a slick-fielding second baseman who batted .308 in more than 2,000 Organized Baseball at-bats – and everything to do with the color of his skin. Teammates often objected to playing with a Black man, and opponents objected to playing against one.

Like the handful of other Black players on predominantly white teams in that era, Fowler was peppered with epithets, and was frequently the target of pitches to the head and ribs and spike-high slides. It got so bad that Fowler and his contemporary, Grant, reportedly designed wooden shin guards to protect themselves from “leg-slashing” base runners.

Despite the unrelenting bigotry, Fowler continued to play on integrated teams, even captaining one. But by 1899, color bans were firmly established throughout Organized Baseball.

“My skin is against me,’’ he wrote four years earlier. “If I had not been quite so black, I might have caught on (in the white majors) … The race prejudice is so strong that my black skin barred me.”

This sentiment was echoed by The Sporting Life, a 19th century baseball bible, which proclaimed: “With his splendid abilities, he would long ago have been on some good club had his color been white instead of black. Those who know say there is no better second baseman in the country.”

Fowler’s historical impact would go beyond his color-breaking moment. As Society for American Baseball Research member Brian McKenna wrote: “He was also one of the first significant black promoters, forming the heralded Page Fence Giants and other clubs and leagues. Wherever there was an effort to form a black league during the 19th century, Fowler could be found in the mix … white field managers and business managers through the country sought Fowler’s advice on fellow black players, at times hiring a man sight unseen for their roster on his say-so. Moreover, Fowler was the one who organized the first successful black barnstorming clubs, a subsequent staple of their industry.”

Cooperstown High School baseball team members wore “Fowler” nameplates on their jerseys during the 2013 season in honor of Bud Fowler, who grew up in Cooperstown and later became one of the earliest Black professional baseball players. The players dressed in uniform as the Village of Cooperstown dedicated “Fowler Way” on April 20, 2013. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum).

Share this image:

King Solomon White, better known as Sol White, also would wear many caps. He earned fame as a hard-hitting infielder, innovative manager and founder of some of the top independent all-Black teams of the 19th century, including the powerhouse Philadelphia Giants, which often beat all-white major league teams in exhibition games and became the forerunners of the organized Negro Leagues.

But White’s greatest contribution – and a huge reason he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2006 in a special vote by Black baseball historians – was the work he did with a pen rather than a bat.

In 1906, White wrote the “History of Colored Baseball,” the only known book about 19th century Black baseball. This invaluable, 128-page guide featured hundreds of photographs and numerous articles, including “How to Pitch,” by Negro Leagues founder Rube Foster, who was regarded as the “Black Christy Mathewson” after recording 44 consecutive victories for the Philadelphia Cuban X-Giants in 1902.

White contributed several articles, too, and in one of them he wrote about a completely integrated game down the road: “Baseball should be taken seriously by the colored player, as honest efforts with his great ability will open an avenue in the near future wherein he may walk hand-in-hand with the opposite race in the greatest of all American games – base ball.”

Noted historian John Holway credits White, Foster and others for holding “black baseball together throughout 60 years of apartheid, making Jackie Robinson’s debut possible.” White, who died in 1955, lived long enough to see Robinson break baseball’s color barrier once and for all.

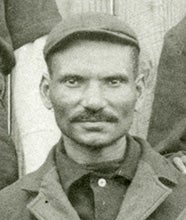

One of the players that White played with and managed was Ulysses “Frank” Grant. Though he never played in the white majors, Grant is regarded by many historians as the greatest Black player of the 19th century. Wrote White of his fellow 2006 Hall of Fame inductee: “Frank Grant … in those days, was the baseball marvel. His playing was a revelation to his fellow teammates, as well as spectators. In hitting, he ranked with the best and his fielding bordered on the impossible. Grant was a born ballplayer.”

As evidenced by his batting averages of .344, .353 and .346 during his three seasons as a second baseman with the Buffalo Bisons of the International League from 1886-88, it was clear Grant would have excelled in the white majors had there not been a color ban.

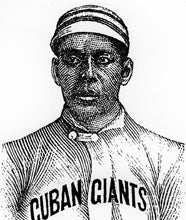

Though small in stature (5-foot-7, 155 pounds), Grant packed a wallop, leading the IL in home runs (11) and extra-base hits (49), while also topping the Bisons in stolen bases (40). After Organized Baseball outlawed Black players in 1889, Grant joined the Cuban Giants, and continued his diamond domination with Black baseball’s preeminent teams until his retirement in 1903. William Edward White is believed by some to be the first Black player in the majors (1879). His mixed heritage and light complexion reportedly enabled him to pass himself off as a Caucasian and avoid the racial prejudice future Black players would encounter. His MLB career, though, lasted just one game. Five years later, catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker joined the Toledo Blue Stockings and became one of the last Black players to appear in a game in the segregated major leagues. Walker would be subjected to constant abuse from opponents, fans, the press and even some of his teammates. Blue Stockings pitcher Tony Mullane made no secret of not wanting to play with Walker, routinely throwing pitches that weren’t signaled just to cross up his catcher. Despite being an avowed segregationist, Mullane conceded years later that Walker “was the best catcher I ever worked with.” Injuries would limit Walker to just 42 games, and he was released before the end of the 1884 season, finishing with a .263 batting average, third best on the team and 23 points above league average. His brother, Welday Walker, also played a handful of games for Toledo that year. The man known as “Fleet” would hook on with the International League’s Newark Little Giants, and in 1887 teamed with pitcher George Stovey to form the first Black battery in white professional baseball. Stovey would win 35 games that season. Walker spent the following two seasons with the Syracuse Stars before being released. He would be the last Black player in white professional leagues until Robinson suited up for the Montreal Royals, Brooklyn’s top farm club, in 1946.

Scott Pitoniak is a freelance writer from Penfield, N.Y.

Related Stories

The Negro National League is Founded

#Shortstops: Words on pictures tell fascinating Negro Leagues story

Pictures tell tale of Negro League legends

The Negro National League is Founded

#Shortstops: Words on pictures tell fascinating Negro Leagues story