Fighting for Equality on the Baseball Grounds

Prior to the Civil War, baseball had largely been restricted to cities and states in the Northeastern and Midwestern United States. However, during the conflict, the game spread quickly, as teams of soldiers from both the Union and the Confederacy would play games of baseball at their camps. Even prisoners of war used the game to pass time while awaiting their release.

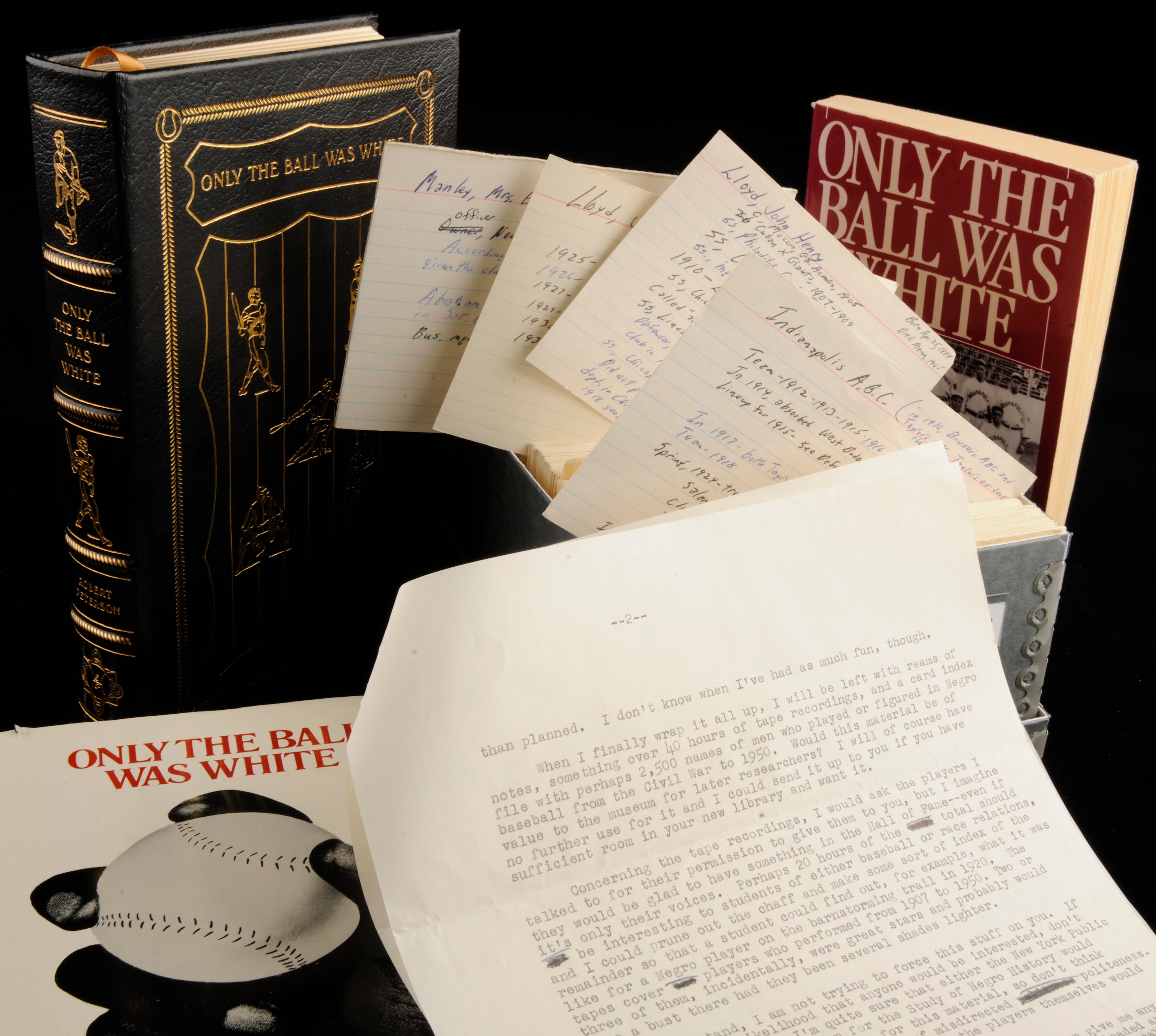

After the war, baseball proliferated across every corner of the re-unified nation, reaching all interested audiences, regardless of race, ethnicity or socioeconomic status. But as was the case among day-to-day affairs on a national level, though slavery no longer existed, inequality was still pervasive in baseball.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

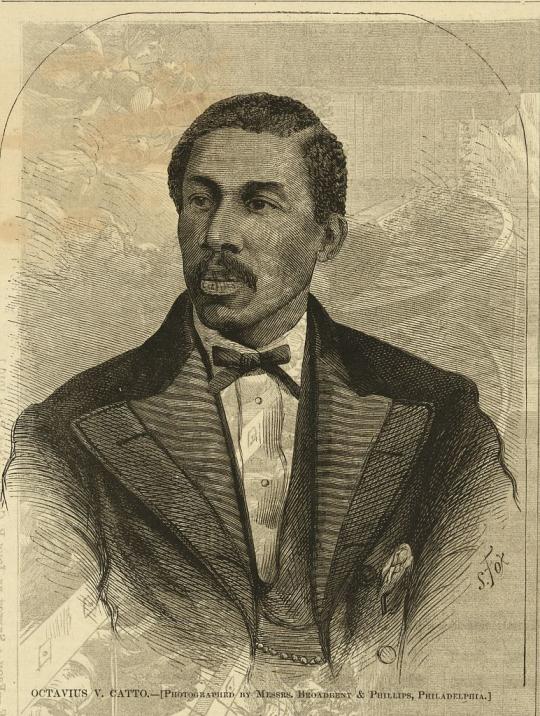

Octavius V. Catto was born – as a free man in a prominent mixed-race family – in 1839 in Charleston, S.C. Not long after his birth, Catto’s parents moved their family north, first to Baltimore and then to Philadelphia. Educated mostly in Philadelphia, Catto would attend the Institute for Colored Youth (ICY) and later become a prominent member of the institute’s staff. He also was a major figure at the Banneker Institute, another mainstay of African-American life in Philadelphia.

In 1866, faced with restrictions against joining white baseball clubs in Philadelphia, the city’s first African-American team, the Excelsior Base Ball Club, formed. Encouraged by this move, Catto and his friends, particularly Jacob C. White, Jr., created their own team. Comprised of individuals from the ICY, the Banneker Institute, as well as other leading social and educational organizations, they called this team the Pythian Base Ball Club.

Despite Hayhurst’s help, the Pythians – the only African American club – were the only club to not receive entry out of the 266 clubs seeking to be a part of the association. Their representative, Raymond J. Burr, withdrew the Pythians’ application when it seemed likely the deciding committee would bow to opposition pressure.

Another application submitted later in 1867, this time to the National Association of Base Ball Players, failed to receive the consideration the Pythians received from the Pennsylvania association, much less approval. It is said they would not admit “any club which may be composed of one or more colored persons.”

In the face of being barred from joining the ranks of white baseball clubs, Catto and the Pythians persevered on the field. Public outcry grew in Philadelphia for a game between the Pythians and a white counterpart. On Sept. 3, 1869, such an event would come to fruition, as the Pythians squared off against the Olympics club. Though the Pythians would take an early lead, the Olympics handily won. Yet the African American showed themselves to be more than worthy competition, and the Pythians would later compete against other white clubs.

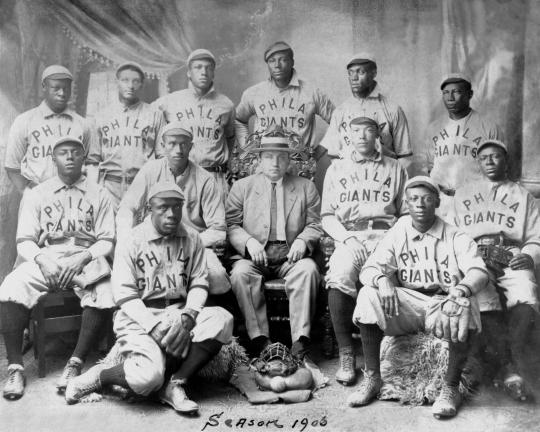

After Catto’s death, the Pythian Base Ball Club ceased to compete, citing the loss of its leader, though individual members continued to play. The Pythian name would reappear in 1886, linked to a baseball team in the National League of Colored Baseball. That team, however, would be short-lived, folding the following year.

Schools and other organizations honored Catto’s memory by placing his name on their buildings. More than 130 years following his death, a headstone was placed at Catto’s burial site in a cemetery outside Philadelphia, ensuring that he will not be forgotten by those dedicated to improving the lives of others.

Matt Rothenberg was the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum