- Home

- Our Stories

- Night games gave access to baseball to millions

Night games gave access to baseball to millions

It was an idea born almost the moment the incandescent light bulb became a reality. Its execution, however, required more than five decades of perseverance – as technological advances, economic necessity and a few brilliant men finally wore down the opposition.

Today, baseball fans born after 1935 have grown up knowing almost nothing but night baseball. But for more than 70 years, big league baseball was played exclusively during the day.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

In some circles, the debate of its merits still lives. But the impact of baseball under the lights is beyond question, as one of the game’s most important innovations of the 20th century.

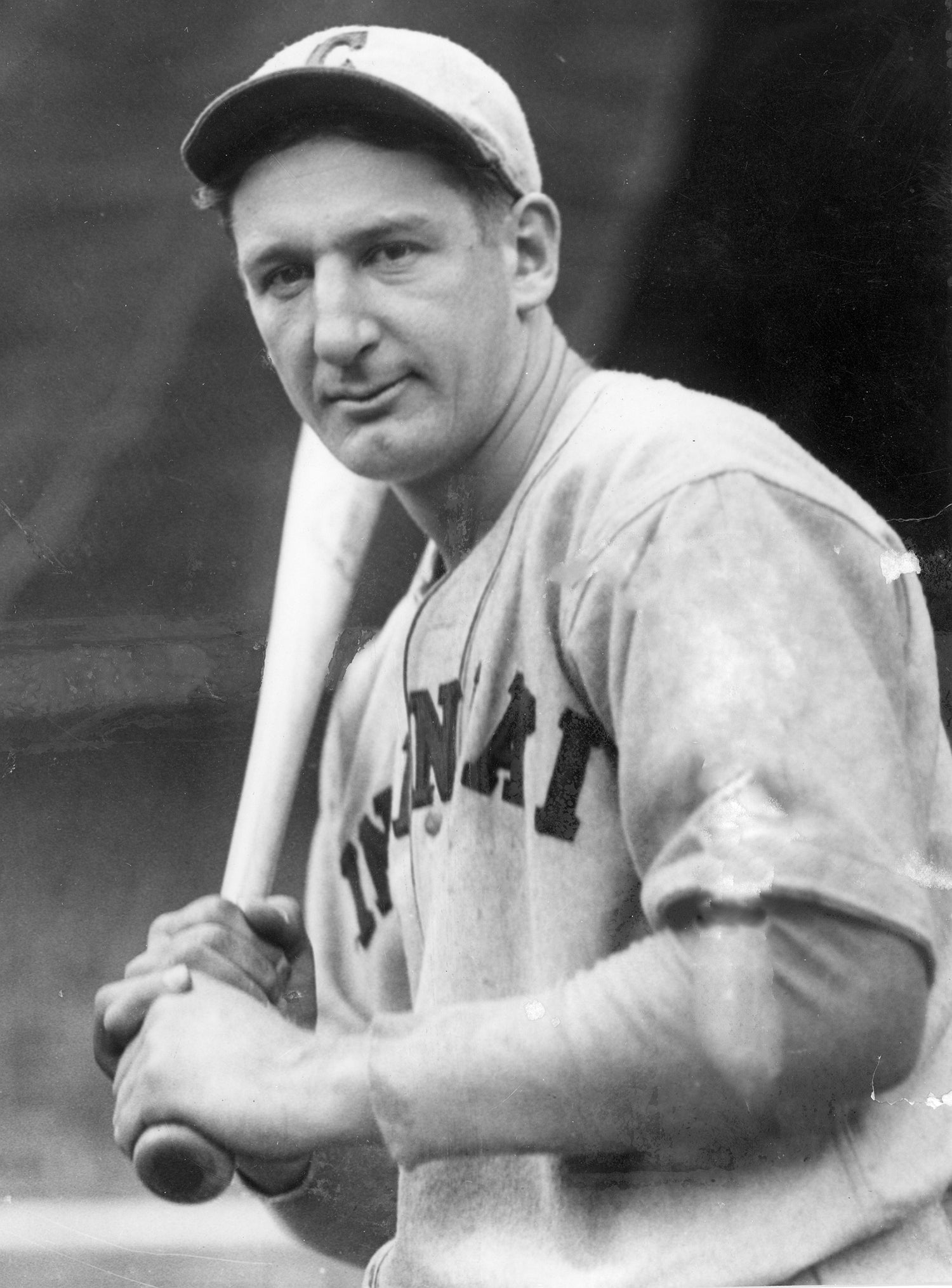

On May 24, 1935, the first night game in major league baseball history was played at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, where the home team defeated the Phillies, 2-1. At 8:30 p.m., President Franklin D. Roosevelt threw a ceremonial switch at the White House in Washington, and the lights went on in Cincinnati.

“As soon as I saw the lights come on, I knew they were there to stay,” recalled the late-Red Barber, the Reds broadcaster at the time, who would win Ford C. Frick Award in 1978. “The lights were perfect. There were no shadows. Everything was lovely.”

It was a tightly, played, exciting pitcher’s duel, held before a crowd of 20,422 – the third largest crowd of the season for the financially struggling Reds. The average attendance for day games in Cincinnati in 1935 hovered around 2,000.

“No pun intended, but there was electricity in the air – on the field, in the stands, and in the dugout,” said Reds first baseman Billy Sullivan at the time.

Several papers reported that there was an excitement in the air akin to an All-Star Game, itself a recent invention in 1933. Ballpark usher Ralph Ploews recalled in a later article that the audience was mesmerized: “People were in utter joy. They gasped.”

Cincinnati Enquirer reporter James T. Golden, Jr. wrote that the field looked far greener at night than during the day, and that balls hit high in the air “stood out against the sky like a pearl against dark velvet.”

Despite the fanfare surrounding the first major league game under the lights, night baseball was by no means a new concept when it came to the majors 75 years ago. The first experiment in night baseball transpired 130 years ago, on Sept. 2, 1880, when two department store teams pioneered the concept in Hull, Mass., just a year after Thomas Edison perfected the design of the electric light bulb. Another night game first occurred on June 2, 1883, when visiting Quincy (Ill.) defeated a local team at Fort Wayne (Ind.). Several more minor league night games were held in the 19th century.

The first night game in Cincinnati, between two Elks Club teams, was actually held in 1909, at the Palace of the Fans – the Reds ballpark prior to construction on the site where Crosley Field would later stand. The following year, a night contest was held at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, between two local semi-pro teams, before 20,000 fans. Ironically, the White Sox themselves were in New York, playing to a 6-6 tie in a game called on account of darkness.

Yet none of these pioneering efforts gained much traction, and the true advances in night baseball lighting were made in the minors, the Negro Leagues and by barnstorming clubs, such as the House of David team.

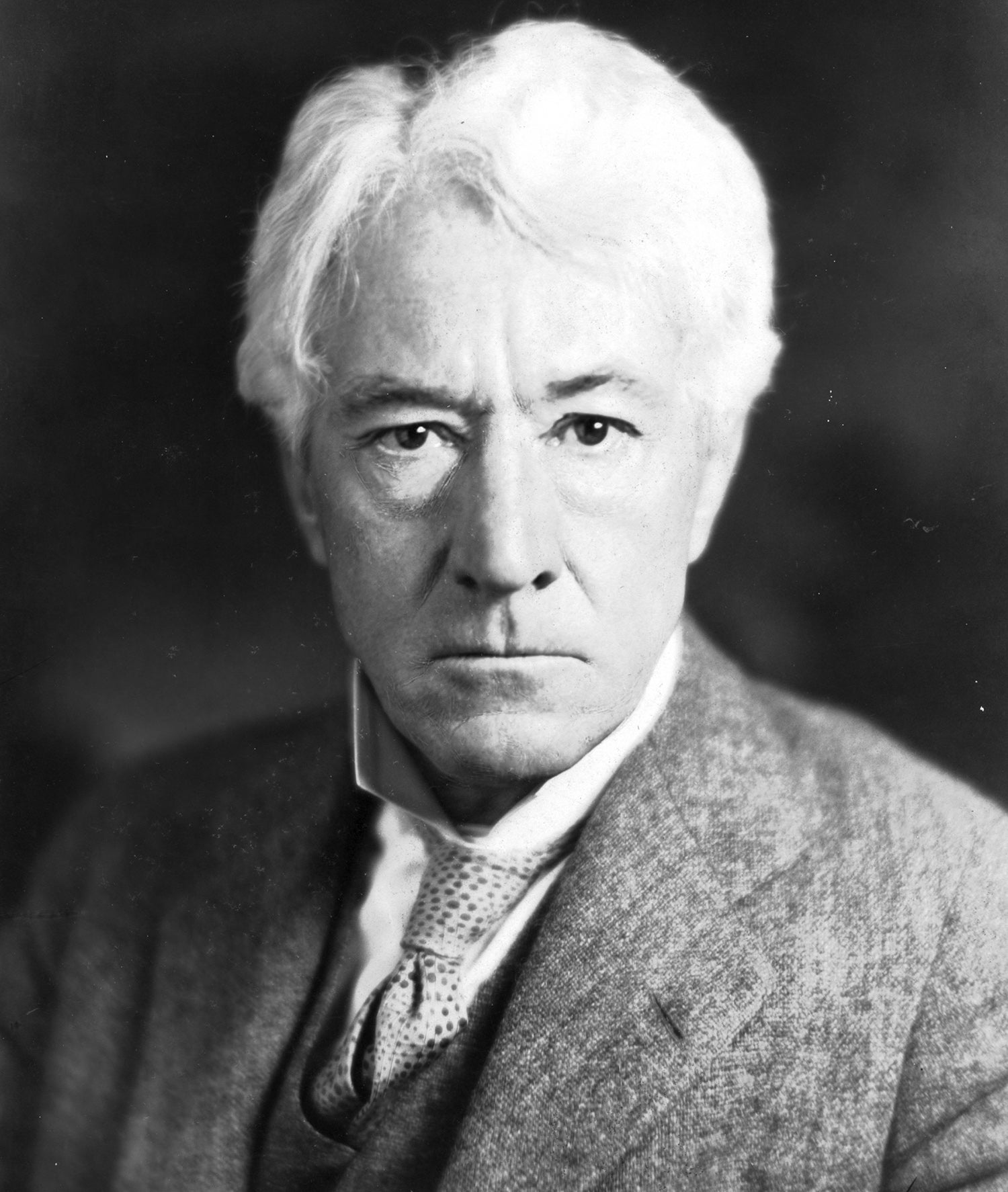

“What talkies are to the movies, night baseball will be to baseball,” prophetically said J.L. Wilkinson, owner of the Kansas City Monarchs, one of the Negro Leagues’ flagship franchises, and a 2006 Hall of Fame inductee. In the early 1930s, Wilkinson created a portable lighting system that could be towed behind the team bus and set up almost anywhere, allowing his teams to play more often and earn more money to ensure their survival.

The first professional baseball night game held under a permanent lighting system took place May 2, 1930, at Des Moines, Iowa, where the hometown Demons beat the Wichita Aviators, 13-6. The game was broadcast nationally by NBC radio, and Demons owner Lee Keyser told the nation that the players and fans were happy, and the night game “means that the Minor Leagues will now live.” Twelve thousand fans came out that night, 20 times the average 600 in attendance for a day game.

Night baseball quickly caught on in the minors and did much to reinvigorate attendance, helping draw fans out into the cooler night air in the days before home air conditioning was widespread.

The rapid growth of night baseball in the minors in the first half of the 1930s did not go unnoticed in Major League Baseball circles. The Depression hurt the coffers of all businesses, and baseball was no exception. But an aura of gimmickry seemed to some to be part and parcel of the night baseball experience.

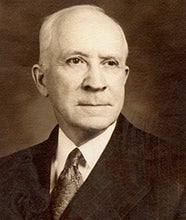

Hall of Famer Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators, once said: “There is no chance of night baseball ever becoming popular in the bigger cities. People there are educated to see the best there is and will only stand for the best.

“High class baseball cannot be played at night.”

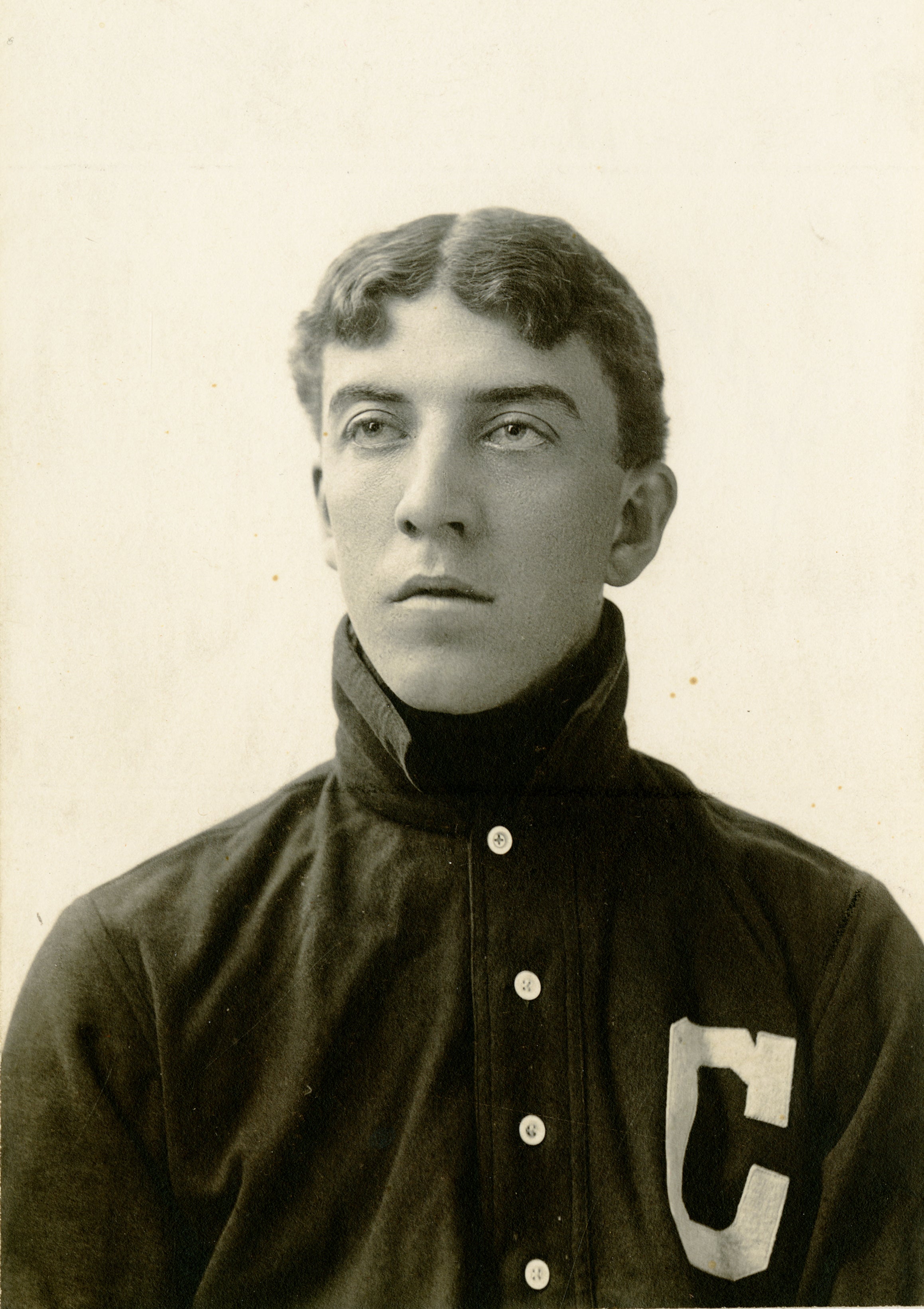

Commissioner Landis initially said to future Hall of Famer Larry MacPhail, general manager of the Cincinnati Reds at the time of the first night game: “Young man…not in my lifetime or yours will you ever see a baseball game played at night in the majors.”

Yet faced with a dire financial outlook in Cincinnati, MacPhail and Reds owner Powell Crosley changed the Commissioner’s mind, and he allowed the Reds to host seven night games in 1935. The numbers quickly grew, and 11 of the 16 major league clubs had installed lights by the time the United States entered World War II.

By the end of the War, only the Red Sox, Tigers and Cubs were holdouts. The Red Sox installed lights in 1947, and the Tigers in 1948. Phil Wrigley of the Cubs held out until 1988, saying that baseball was meant to be played in the sunshine. Wrigley had actually ordered lighting materials after the 1941 season, but when Pearl Harbor was attacked, he immediately donated all the material to the War Department for use in lighting “flying fields, munitions plants, or war defense plants.”

The Cubs finally added night baseball to their offerings on Aug. 8, 1988, though many of their home games are still played in the day.

There was a night baseball doubleheader played at Wrigley Field long before 1988, however. On July 1, 1943, two all-star teams from the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League, Wrigley’s brainchild, played a shortened doubleheader under a temporary lighting system.

The Hall of Fame’s collections have been vastly enriched by donations related to the first major league night game at Crosley Field. In 1970, the Reds donated their files and records relating to the development of lighting at Crosley Field to the Hall of Fame. The collection includes ball park diagrams, correspondence, and proposals from three companies to handle the installation: Westinghouse, Giant Projectors, and the ultimately successful bid from General Electric.

The following year, the National League gave the Museum a scrapbook containing press clippings, photos, and editorial cartoons documenting the development of night baseball in each of the original eight NL cities.

The Hall of Fame Library additionally houses a collection of 30 photographs of the first night game from Major Bob Payne, a retired Army chaplain and author of a book about night baseball, whose father, Earl D. Payne, was one of the Cincinnati Gas and Electric lighting engineers who worked on illuminating Crosley Field.

The Hall of Fame has two baseballs from Crosley Field from the night of that historic game. One was kept by future Hall of Fame umpire Bill Klem, and the other is signed by a host of players and others, and includes the statement: “The lights are swell.”

Hall of Famer Lee MacPhail donated a beautiful painting entitled, “The First Major League Game Ever Played Under Floodlights,” painted by H.M. Mott-Smith for General Electric’s 1936 promotional calendar.

It seems that the words of J.L. Wilkinson have proved to be true: Lights are to baseball what talkies are to the movies.

Tim Wiles was the director of research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Joss, MacPhail elected to Class of ’78

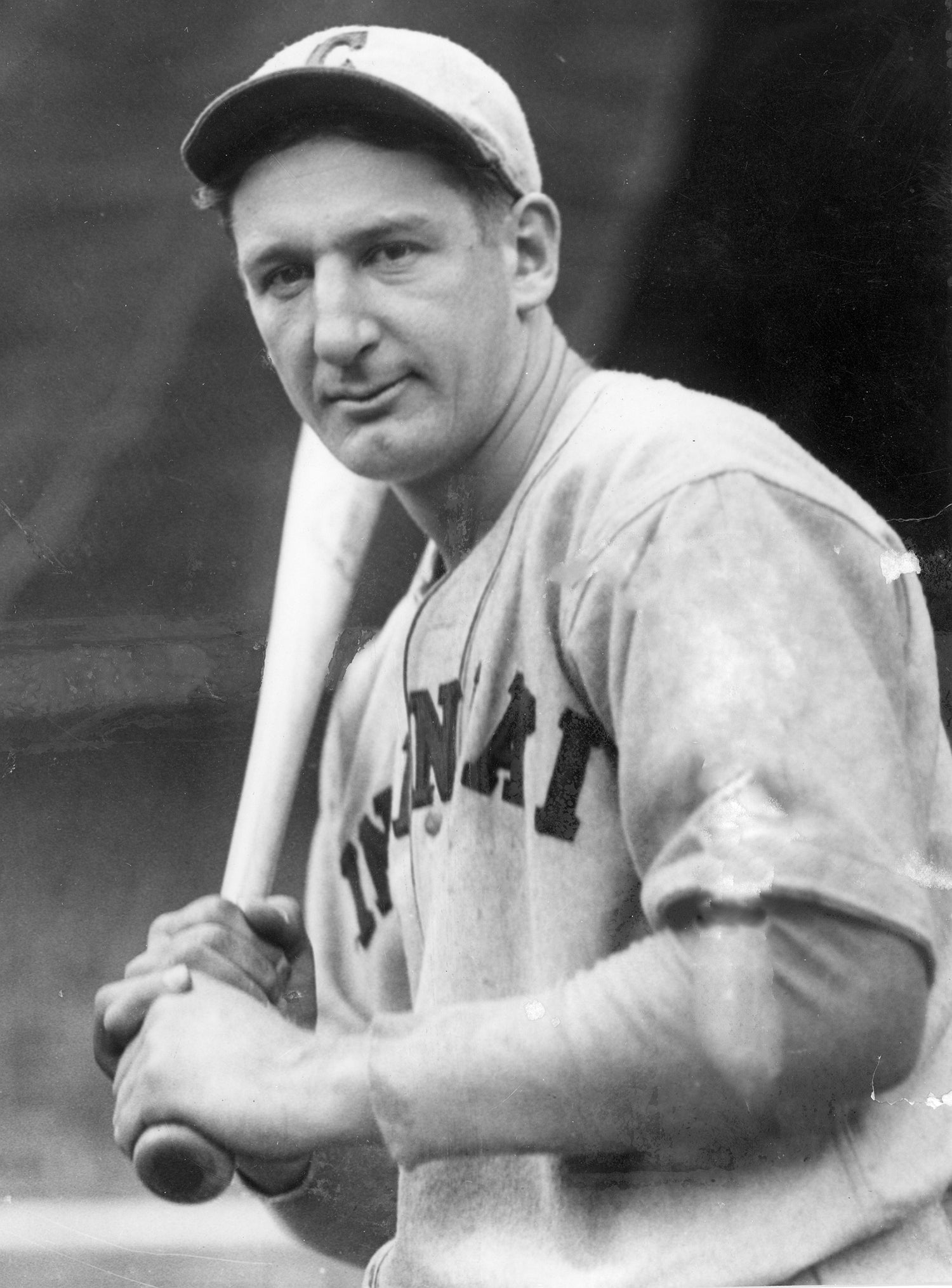

Reds sell Lombardi’s contract to Braves

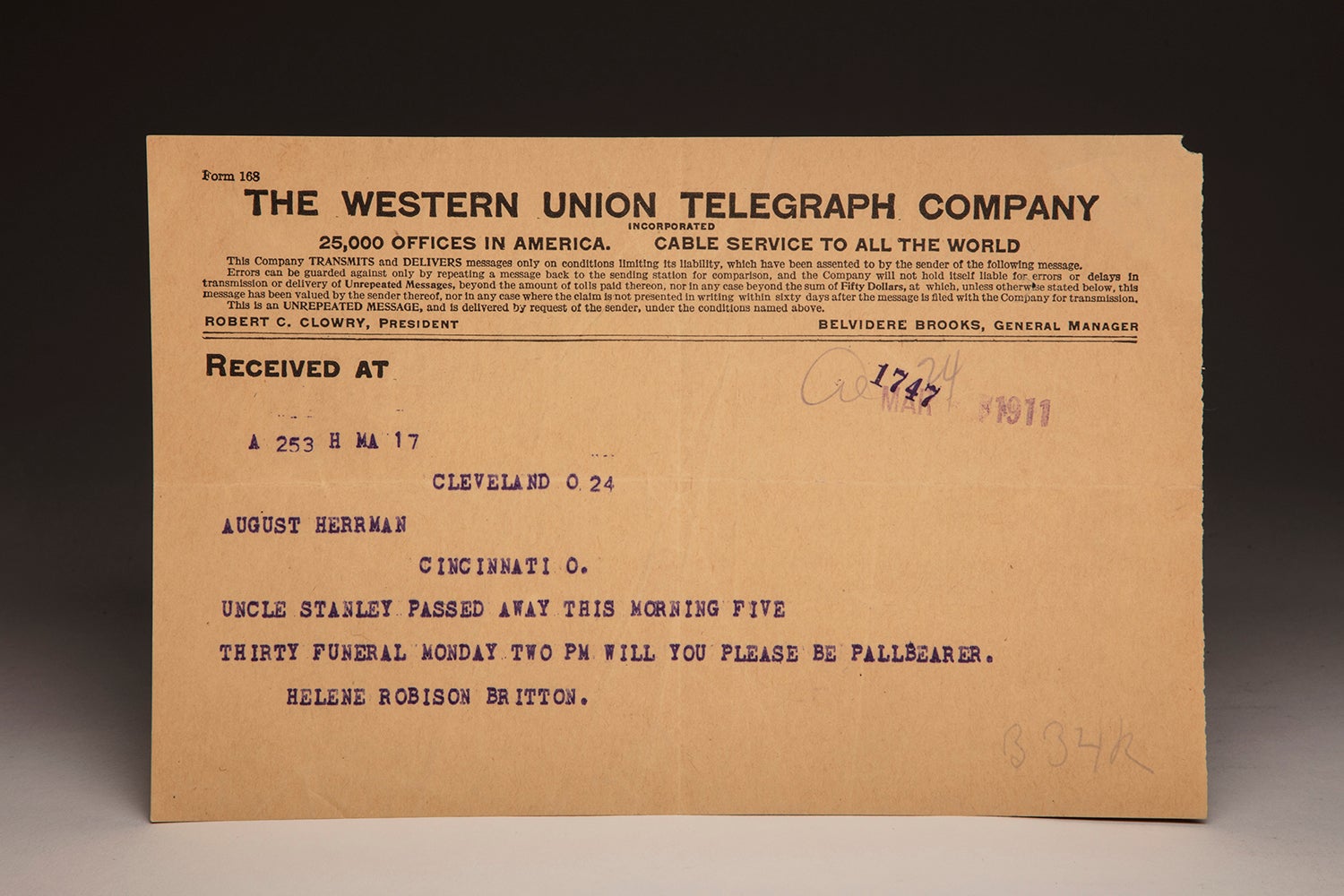

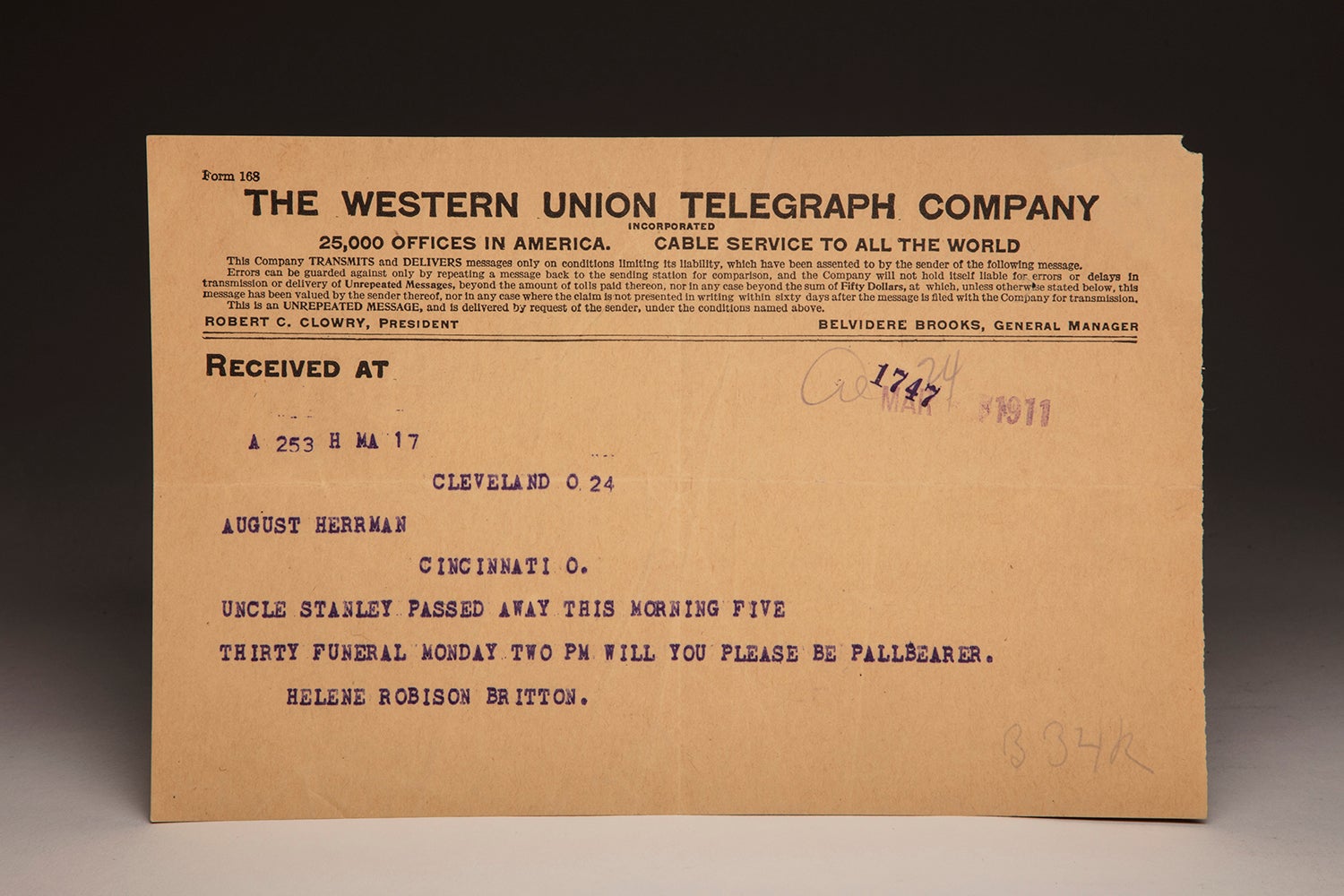

A telegram that changed baseball history

AAGPBL shined a light at Wrigley Field in 1943

Joss, MacPhail elected to Class of ’78

Reds sell Lombardi’s contract to Braves

A telegram that changed baseball history