- Home

- Our Stories

- Museum’s Shoebox Treasures exhibit features stuff of collectors’ dreams

Museum’s Shoebox Treasures exhibit features stuff of collectors’ dreams

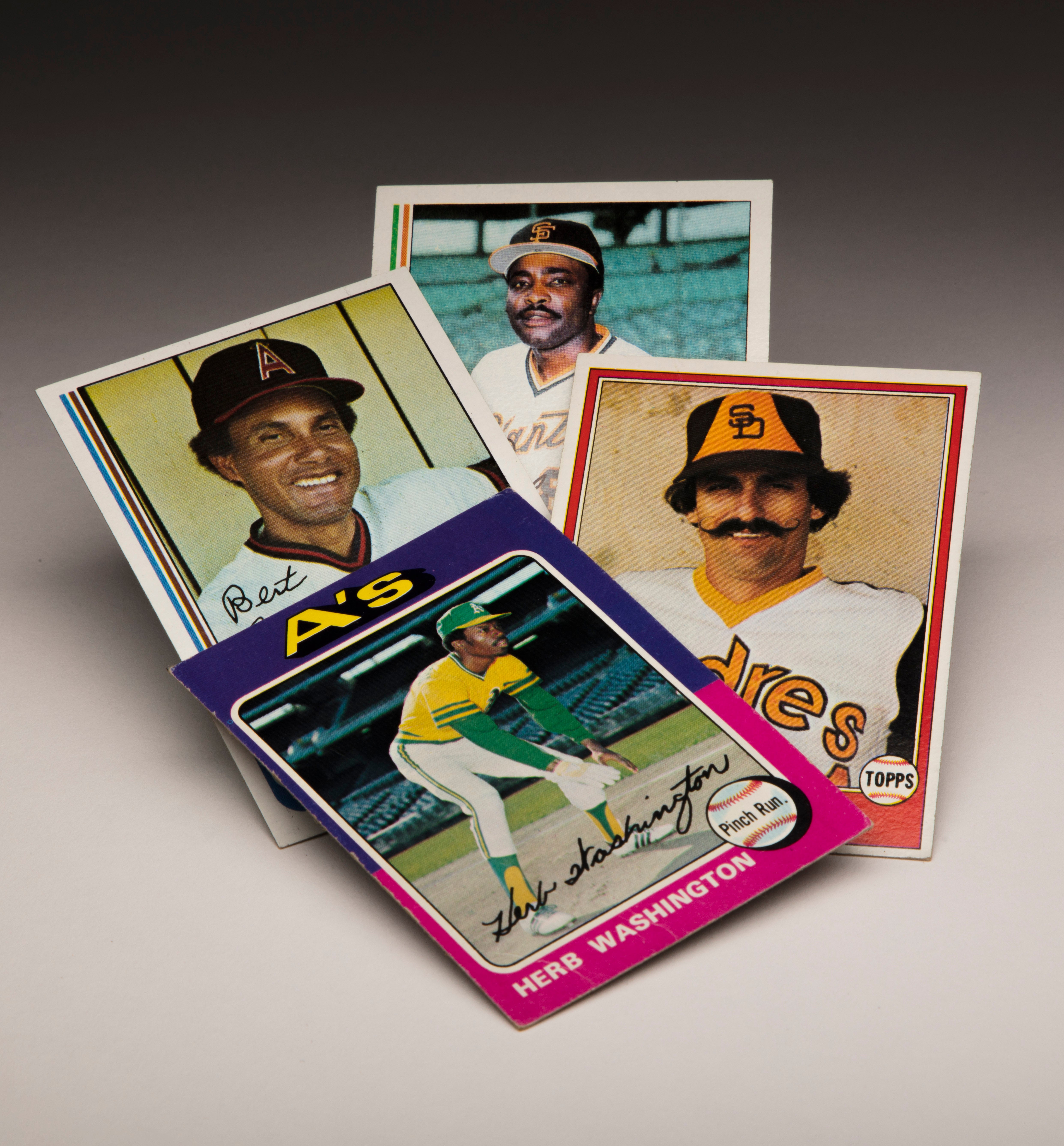

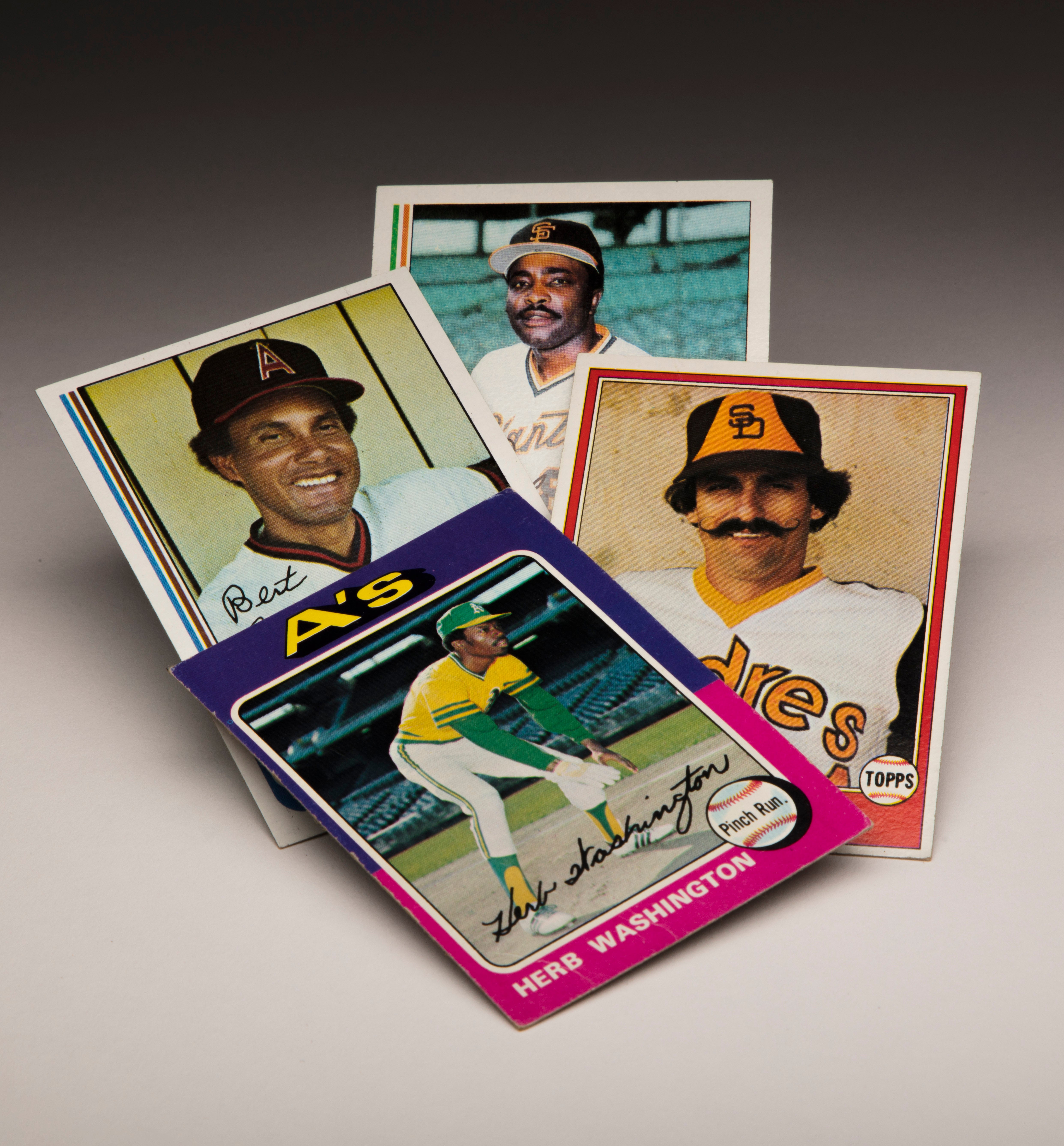

The Hall of Fame’s Shoebox Treasures exhibit showcases some of the most prized cards in the history of one of America’s most beloved hobbies.

While no individual collection can stake claim to possessing every baseball card ever made, the collection at the Hall of Fame and Museum features many of the most iconic pieces of cardboard ever produced.

Some of the cards are noteworthy because of their rarity. Others stand out because of their unusual nature, one in particular for showing a player that never actually existed. All of the cards are essential in telling the story of a hobby that is almost as popular as the sport itself.

Here are a few such gems from the Museum’s collection.

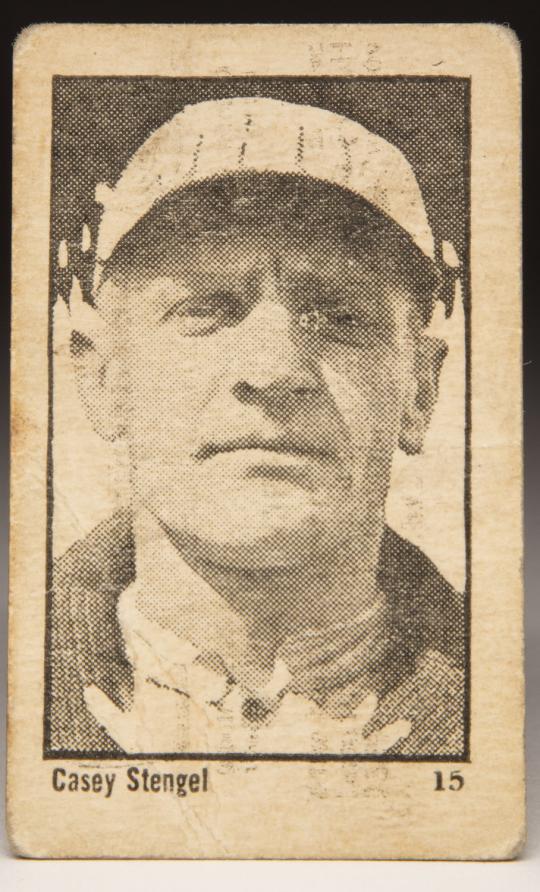

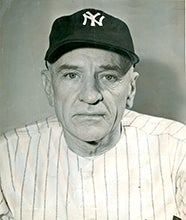

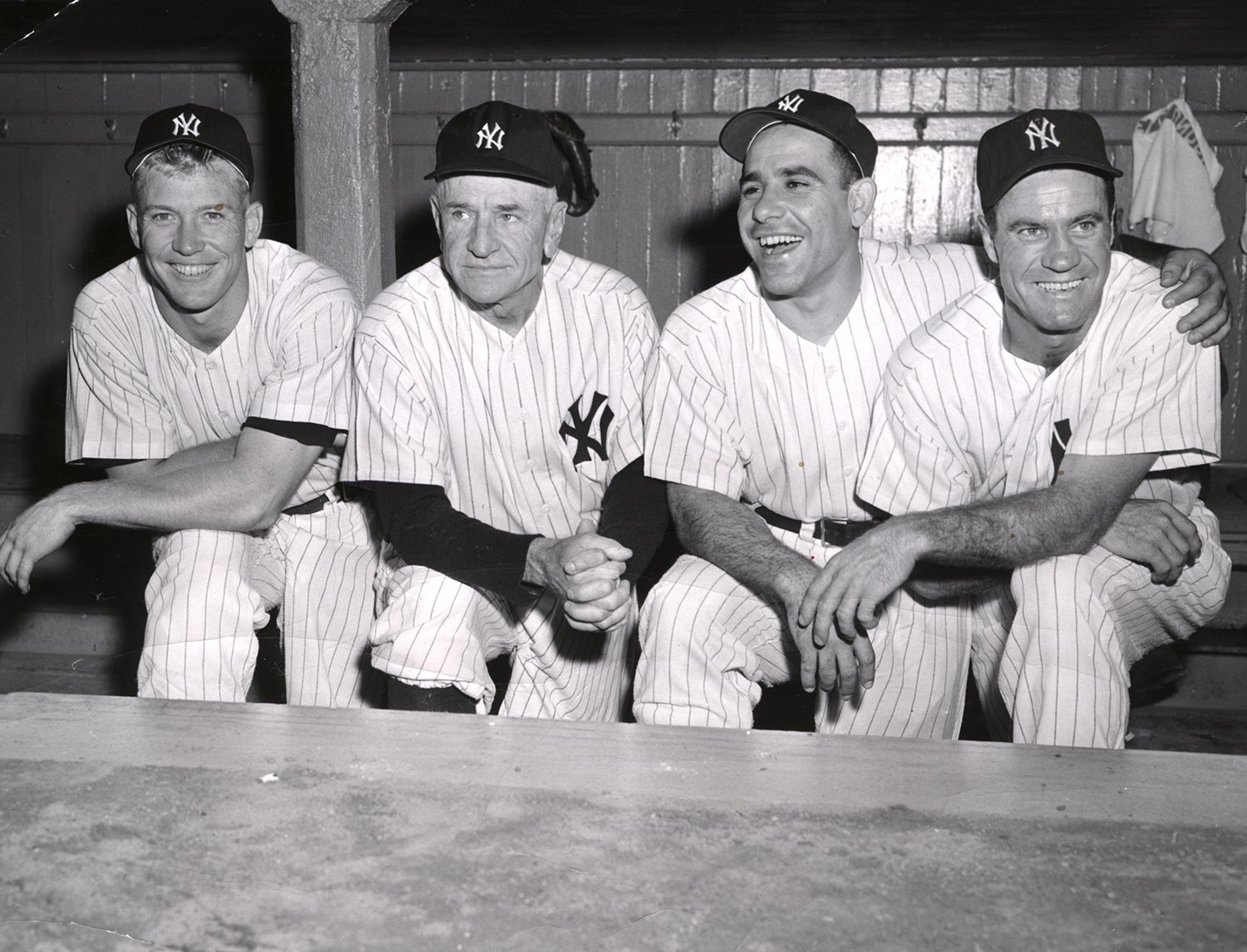

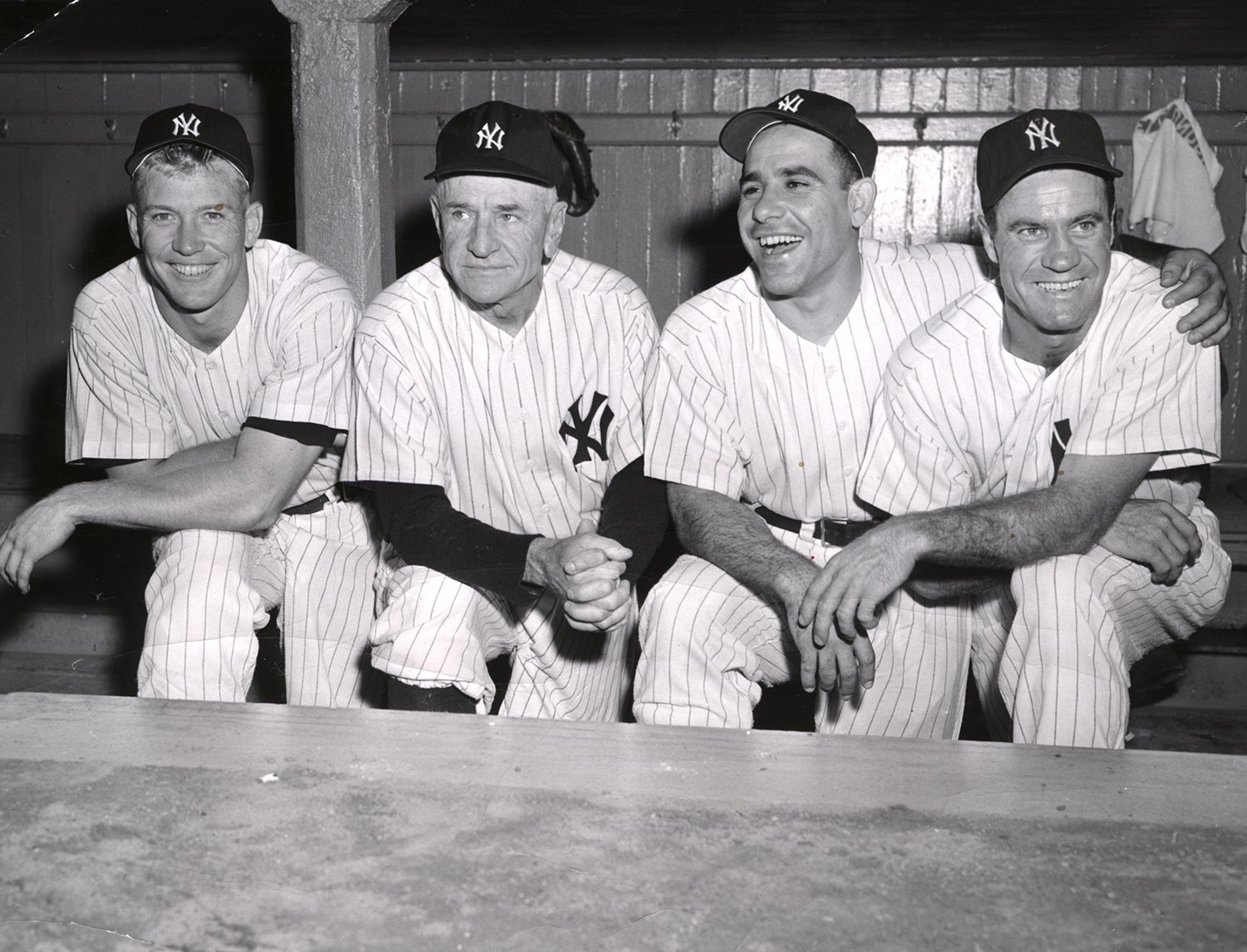

1923 Maple Crispette: Casey Stengel

If you’re not a diehard collector of cards, you might never have heard the words “Maple Crispette.” Those words refer to the name of an old-time candy company based in Montreal. For years, Maple Crispette had produced a variety of candy, popcorn, and marshmallows, but in 1923, the company decided to include cards with some of their snack purchases.

The inaugural set featured 30 cards, including heavy hitters (and pitchers) like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth and Walter Johnson. But none of those cards would become the most valuable in the set. That honor would belong to Casey Stengel, at the time an outfielder with the New York Giants but who would gain far more fame as a Hall of Fame manager.

As an incentive to buy the candy, Maple Crispette put together a promotion. Fans who collected the entire set of 30 cards could turn them in for sporting goods equipment. Not wanting to hand out too much baseball-related hardware, the company intentionally short-printed the Stengel card, making it difficult to assemble the entire set.

Since their publication in the 1920s, the already short supply of Stengel cards became diminished because of time and other circumstances. In fact, the number of Stengel cards has dwindled to one – and it is part of the collection at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

That’s it – one Stengel card. You won’t find it anywhere else but Shoebox Treasures.

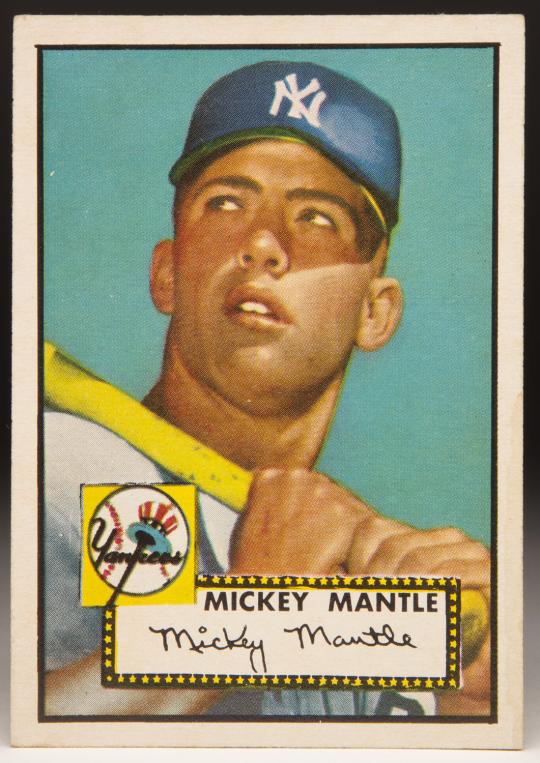

1952 Topps: Mickey Mantle

Rather famously, Frick Award-winning broadcaster Bob Costas has long carried in his wallet a 1952 Topps card of his idol, Mickey Mantle. That gives us a small taste of the iconic impact of Mantle, a generational player of rarified appeal.

Given the love of Mantle, and given that 1952 Topps represented the company’s first successful venture into trading cards, it’s no wonder that the Mantle card has achieved its status as one of the industry’s most prized items. Some collectors refer to it as the “most recognizable card in the hobby.”

Even though it’s not a rookie card, the ’52 card has become the most desired of all the Mantles. It features a beautifully colorized black-and-white photo; the colors, particularly the blue and the yellow, are vibrant and lively, making it an aesthetically pleasing card.

Several years after producing the 1952 set, Topps executive Sy Berger decided to discard the unsold cards, literally dumping them into the Atlantic Ocean. Little did Berger know that he was creating a smaller supply for the future secondary market, one that Berger and the rest of Topps did not even realize would come to fruition; with fewer cards, including the Mantles, available to future collectors, the card became rarer and more valuable.

How rare? In terms of cards graded 9 or better, only nine of the ’52 Mantles are said to exist. How valuable? In 2018, one of the ’58 Mantles sold at auction for $2.8 million.

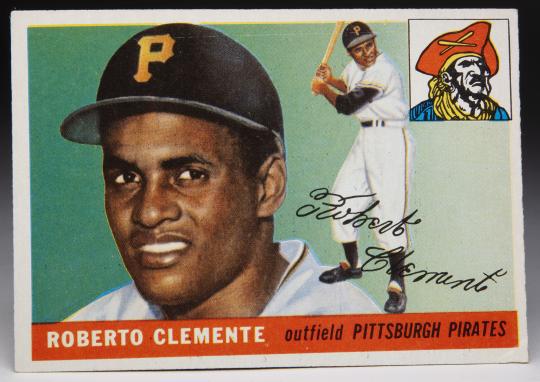

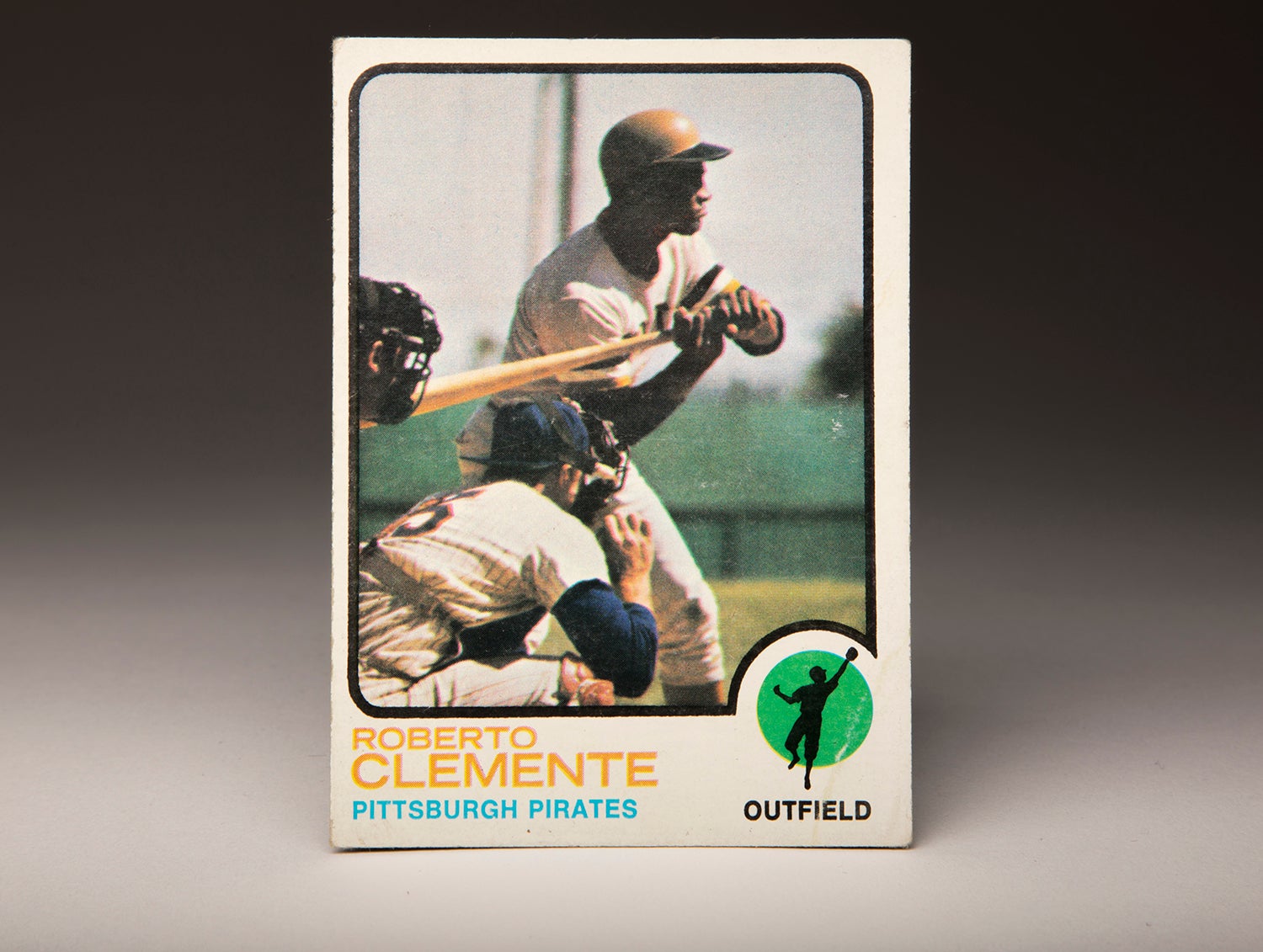

1955 Topps: Roberto Clemente

Few players have become as beloved as Roberto Clemente, a true American hero who lost his life at 38 while trying to perform humanitarian work for the earthquake-ravaged citizens of Nicaragua. Given his heroism and selflessness, along with his status as a Hall of Fame right fielder, it’s no surprise that his rookie card, issued in 1955, has become one of the most hotly desired items in the hobby.

The card’s appeal is only enhanced by its inclusion in the 1955 Topps set, with its against-the-grain landscape format, its vibrant colors, and the inclusion of a stylish facsimile autograph. The ’55 card also stands out because it identifies Clemente by his proper first name of Roberto. After the ’55 card, Topps attempted to Americanize Clemente by referring to him as “Bob,” a practice that continued through the 1968 set, before finally ending in 1969.

The 1955 set also features rookie cards of two other Hall of Famers, Harmon Killebrew and Sandy Koufax. But the Clemente card is harder to find in mind condition; only 11 such Clemente cards are said to exist at a grade level of at least 9, compared to 23 such cards for Koufax and 19 for Killebrew.

The appeal and popularity of Clemente shows no sign of abating. In 2018, a ’55 Clemente card sold for $264,000 at auction.

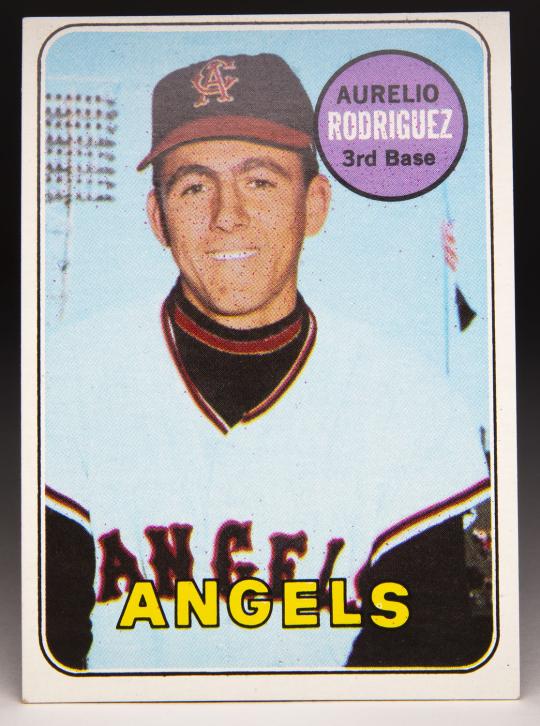

1969 Topps: Aurelio Rodriguez

Some cards are not particularly rare or difficult to obtain. But they are no less intriguing. One such example can be found in the 1969 Topps set; it’s the card purporting to show California Angels third baseman Aurelio Rodriguez. Sometimes called the “original A-Rod,” Rodriguez emerged as the Angels’ Opening Day third baseman in 1969, but he wasn’t so well known that he could avoid a case of mistaken identity.

In a mistake that was not initially noticed, not even by avid collectors, it is not Rodriguez who appears on the card. In later years, the mystery man on the card would be identified as Leonard Garcia. Who was Leonard Garcia? He was the Angels’ batboy in 1968. (Garcia would later become a trainer in the Pacific Coast League.)

For a number of years, some within the industry claimed that Rodriguez had pulled a prank on the Topps photographer. But no evidence has ever been found to show that Rodriguez did anything deceiving.

It was eventually discovered that a stray photograph of the batboy had been mixed in with the other photos in the Rodriguez file, which had all been purchased from famed photographer George Brace. At a time when most major leaguers were refusing to pose for new photographs because of a dispute between Topps and the Players Association, someone at Topps mistakenly chose the Garcia photo, instead of an actual photo of Rodriguez, for the ’69 set.

In retrospect, the error is easy to understand, simply because Garcia and Rodriguez did share some resemblance to each other.

No prank, no plot, simply an honest mistake.

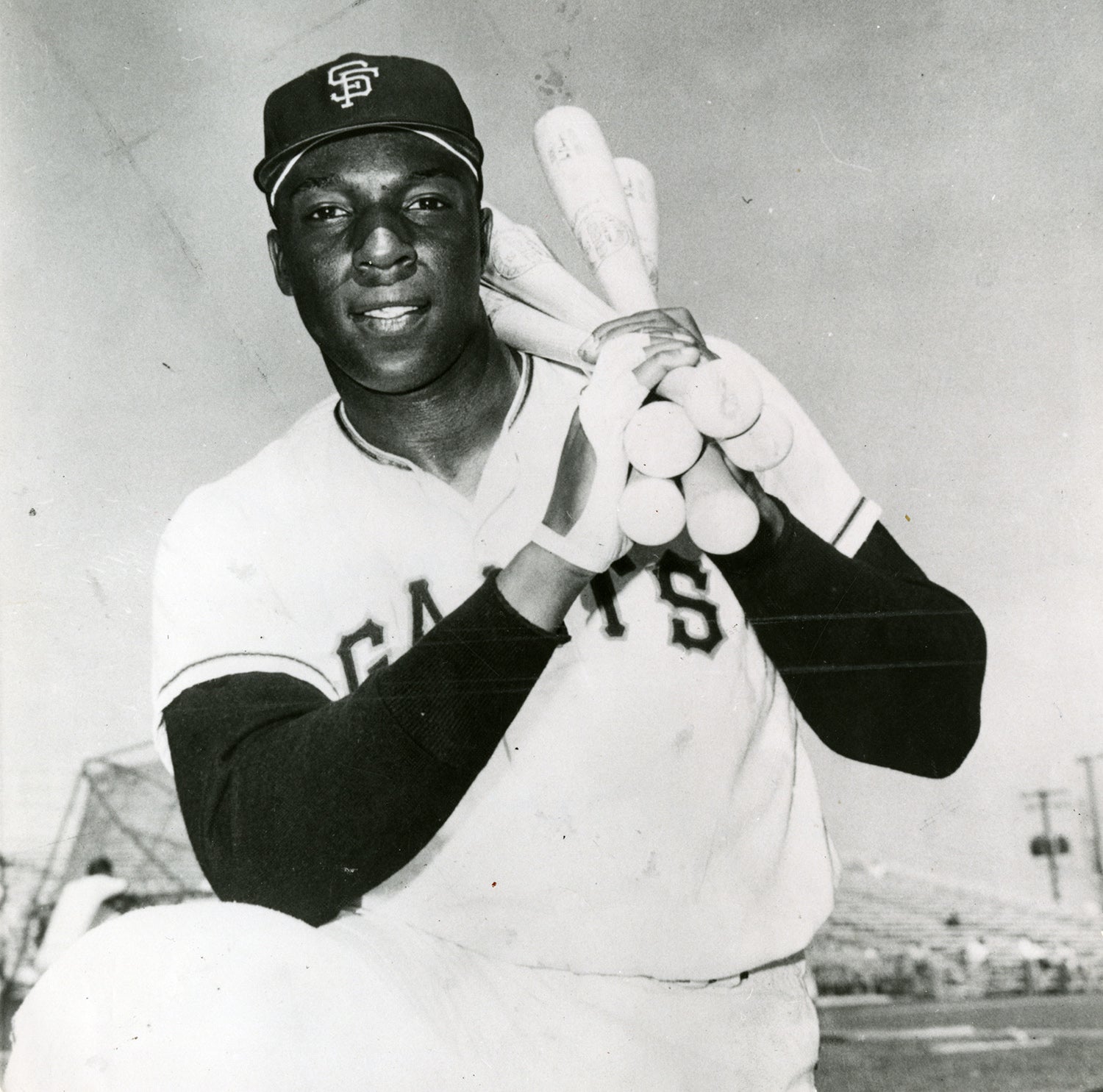

1974 Topps: Willie McCovey

During the 1973 season, rumors circulated about a possible sale of the San Diego Padres. Facing severe cash flow problems, Padres principal owner Arnholt Smith reached a tentative agreement with Joseph Danzansky, a food company magnate, in May of ’73. A number of news organizations reported the sale as a done deal, even though it required the approval of National League owners.

By early December, the sale to Danzansky seemed inevitable. The National League released its 1974 schedule, which showed the city of Washington hosting an Opening Day game on April 4. Over the winter, the Padres acquired several high-priced veterans, including Matty Alou, Glenn Beckert, and Willie McCovey, a further indication of the imminent sale of the franchise to the wealthy Washington owner. Danzansky even began production of new Washington uniforms. But the franchise sale was not official and had not been approved.

Facing a dilemma with regard to its production of a set of 1974 cards, Topps decided to roll the dice. The company printed 13 of the Padres player cards, along with a manager card and a team card, with “Washington” and “Nat’l League” inscribed on banners on the fronts of the cards. Those cards became known as the “Washington Nationals.” One of those cards included an airbrushed shot of McCovey, the Hall of Fame first baseman who passed away in 2018.

Shortly after the cards hit the stores, Arnholt Smith announced the sale of the team to McDonald’s co-founder Ray Kroc. Kroc announced that he had no intention of moving the team out of San Diego. Executives at Topps began to scramble. They halted production of the existing cards and replaced the “Washington Nationals” with cards that featured “San Diego” and “Padres” on the banners of the cards.

As it turned out, Topps produced fewer of the “Washington Nationals” cards than it did the San Diego version of the card. So that makes McCovey’s Washington card rarer. Couple that with McCovey’s status as a Hall of Famer, and the fact that the sale and franchise move never happened, and you have a particularly valuable piece of cardboard.

You might be wondering about another Hall of Famer who played for the ’74 Padres, outfielder Dave Winfield. For some reason, Winfield was one of a number of Padres who was not included in Topps’ “Washington Nationals” adaptation. Winfield’s appearance on 1974 Topps only included the Padres’ version of the card, allowing the McCovey to stand in more exclusive territory.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

Casey Stengel announces his retirement

Doug McWilliams’ photographs for Topps have become part of history at the Hall of Fame

McCovey becomes first player to homer twice in one inning two times

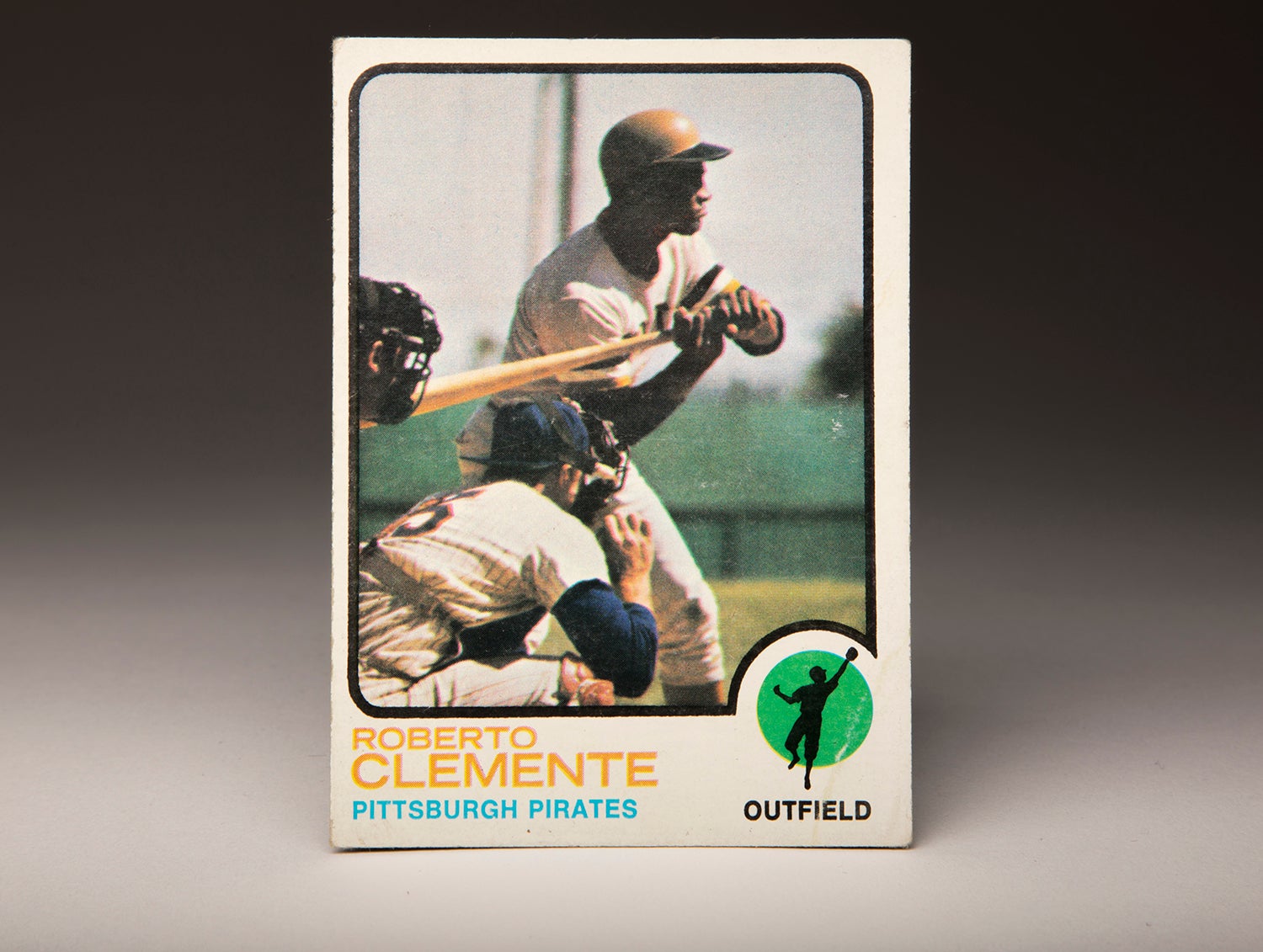

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Roberto Clemente

Casey Stengel announces his retirement

Doug McWilliams’ photographs for Topps have become part of history at the Hall of Fame

McCovey becomes first player to homer twice in one inning two times