- Home

- Our Stories

- Doug McWilliams’ photographs for Topps have become part of history at the Hall of Fame

Doug McWilliams’ photographs for Topps have become part of history at the Hall of Fame

Doug McWilliams spent nearly a quarter of a century photographing players for Topps baseball cards.

Millions of those cards have been lost to bicycle spokes, flipping games and ultimately the trash can. But the pictures remain. Those images, many of which are preserved in Cooperstown and can be found in the Museum's Shoebox Treasures exhibit, are McWilliams’ impressive legacy.

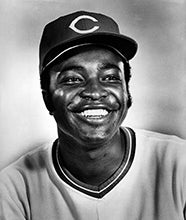

“I think Pat Kelly (the former photo archivist with the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum) said it best: ‘It looks like they all know you!’ That was important to me,” said the 81-year-old McWilliams, whose career with Topps ranged from 1971 through 1994. “I wanted to make the best portraits that I could – by being prepared, and knowledgeable – and being friendly to all that I met.”

McWilliams’ goodwill also extended to an impressive and generous donation to the Cooperstown baseball institution’s Photo Archives, which contains more than 250,000 wide-ranging iconic images of the National Pastime.

“The collection of over 10,000 color negatives that Doug McWilliams donated in 2010 has been invaluable to the Photo Archives,” said Hall of Fame Manager of Photo Archives Kelli Bogan. “These photographs document a period of time that was particularly weak in our archives and McWilliams’ images both fill that void and elevate our entire collection. Since their donation, these have become some of our most requested images from researchers and enthusiasts alike.”

A modern baseball card, at its most basic, is a small, rectangular piece of cardboard, about the size of a credit card, with an image of a ballplayer on one side and biographic and statistic information on the other. Though their intrinsic value is small, their currency often lies in the memories they conjure.

“A card collection is a magic carpet that takes you away from work-a-day cares to havens of relaxing quietude where you can relive the pleasures and adventures of a past day – brought to life in vivid picture and prose,” wrote Jefferson R. Burdick, often referred to as the father of baseball card collecting in America, in the introduction to his seminal text, The American Card Catalog.

Bob Uecker humorously explained a card’s importance.

“I knew when my career was over,” said the former big league catcher and 2003 Ford C. Frick Award winner for broadcasting excellence. “In 1965 my baseball card came out with no picture.”

According to Hall of Fame pitcher Goose Gossage, the thrill of seeing oneself on a baseball card is a cherished memory.

“It kind of legitimizes you. It makes you feel that you’ve made it,” Gossage said. “Once they’re established, a lot of guys say they don’t care about cards, but they still want to look good when their pictures get taken.”

Born and raised in Berkeley, Calif., McWilliams began collecting cards when he was a 9-year-old with money from a newspaper route. But it wasn’t long until – thanks to a fortuitous gift from his father – a youthful passion of taking pictures at nearby Oakland Oaks Pacific Coast League home games in 1950 become a lifelong occupation.

“I had a little folding Kodak my father had given me that I used to take pictures during the games,” McWilliams said. “Some of the pictures were OK, most were pretty bad. But after a while, some of the players began asking if they could buy some of them.”

Soon after earning a degree in photography from the Brooks Institute in Santa Barbara, Calif., McWilliams was doing industrial photography for the University of California’s Lawrence Berkeley Lab.

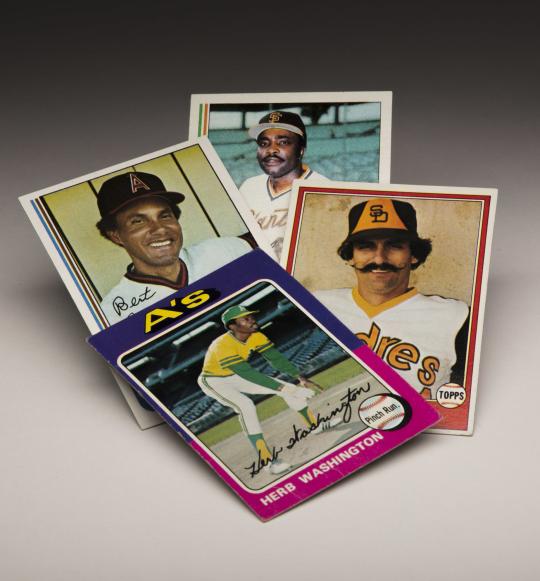

Some of Doug McWilliams' favorite images on Topps card include (clockwise from top center) Joe Morgan's 1982 card, Rollie Fingers 1981 card, Herb Washington's 1975 card and Bert Campaneris' 1982 card. (Topps baseball cards photographed by Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

After the Athletics relocated to Oakland in 1968, McWilliams’ love for the game was rekindled and he found himself again taking photos of the players from the stands. In 1971, a relationship with A’s pitcher Vida Blue led McWilliams’ to producing thousands of color postcards for the eventual American League MVP and Cy Young Award winner to give out to fans.

One of these Blue postcards soon found its way to Topps and a part-time job offer shooting for the top sports card manufacturer was in the cards.

“Until 1981, about all my shooting was in Arizona. Occasionally I would be sent to Los Angeles or San Diego to pick up players new to the team in September,” McWilliams said. “After that, I worked all season long in Oakland and San Francisco. I was the only baseball card photographer in Spring Training until 1981; my last year there were 65 baseball card photogs in Arizona.”

In the spring of 1972, McWilliams’ initial Topps assignment was to head to Arizona and shoot four teams – Athletics, Giants, Cubs and Brewers. Initially a Spring Training photographer, McWilliams’ assignments eventually took him all across the West Coast.

“For the posed shots I used a brand new camera on the market in 1972: A Mamiya RB67. It would give me an image almost as big as the picture on the card, so the quality was outstanding. I had to provide five or six posed images of everyone in camp – players, managers and coaches,” McWilliams said. “Full color transparencies – Ektachrome 120 roll film/ASA 64 film – basically a very large ‘slide’ with electronic flash fill balanced to the sunlight (same exposure for both light sources).

“Also, I had to shoot 15 rolls of Ektacolor 100 ASA negative film – 36 exposures of every game that I saw. So that would be 540 images of candids and game-action shots. For that I used an Asahi Pentax camera at the beginning. Later I went with all Nikon camera and lenses: Model FE and FE2 bodies and 50mm, 90mm, 320mm, 400mm and 800mm lenses with extenders.”

Capturing these baseball figures with color photography is an important aspect to the story.

“The only baseball photographers I generally saw were newspaper photographers, and they only shot black-and-white. Color wasn’t done in printed newspaper back then,” McWilliams said. “I did occasionally see magazine photographers, who would be shooting color, but only a few times a year.”

McWilliams’ role and Topps’ needs evolved over the years.

“When I first started, I was given one day per team to do all that work. I would generally get to the Spring Training site around 8 a.m. Some sites required me to leave my Sun City, Ariz., house at 4:30 in the morning,” McWilliams remembered. “Later on toward the late ‘80s, I would go for three weeks because of so many players and teams as well as the requirements for the eight or 10 different sets being done by Topps.

“My first 10 years I had to have the film processed and identify everyone, then send in the processed film to Topps in Brooklyn. In later years, I would send my exposed film to a lab in New York City every three days via FedEx.”

While the process McWilliams adhered to in producing these historic photos was important, what made them memorable cardboard wonders was often more personal.

“It was a long time before I realized these guys were just regular people – and that came as a great shock to me. I wanted to make images of the players that were as good as I could do, so the fans could see their personalities,” McWilliams said. “I always introduced myself and tried to get to know them in the short time I had with them – although I was there for some of their whole careers. I would only take about a minute to do five or six posed shots.

“I personally liked the rookies. They are always thrilled to pose for you.”

Topps photographer Doug McWilliams takes a picture of San Diego Padres manager and future Hall of Famer Dick Williams during Spring Training in Yuma, Ariz., in 1983. Over more than two decades, McWilliams took photographs of thousands of players and managers, many of which became images on Topps card that are now a part of the Hall of Fame's Shoebox Treasures exhibit. (Fred Kaplan/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

According to McWilliams, it was the intimate relationships formed in these short time periods that often distinguished his shots from the work of others.

“By being friendly, prepared and efficient in my work. I always extended my hand and told them my name, who I was with, and what was needed,” McWilliams said. “Being nice and creating friendships was the most important thing that I brought to the ballpark, my work, and to Topps. And not just the players, managers and coaches, but the batboys, the people in the front office, etc. It would take me about one minute to take the portraits. I was required to do two headshots, two waist-up poses, and two full-length poses. Simulated action, generally, of just have them being casual, I would know before I shot what I was going to ask of them.

“I got to know some of the players very well. I was asked to do their family pictures, weddings, and bar mitzvahs, etc. Of course that did not having any connection to Topps baseball cards – just friendships I developed along the way.”

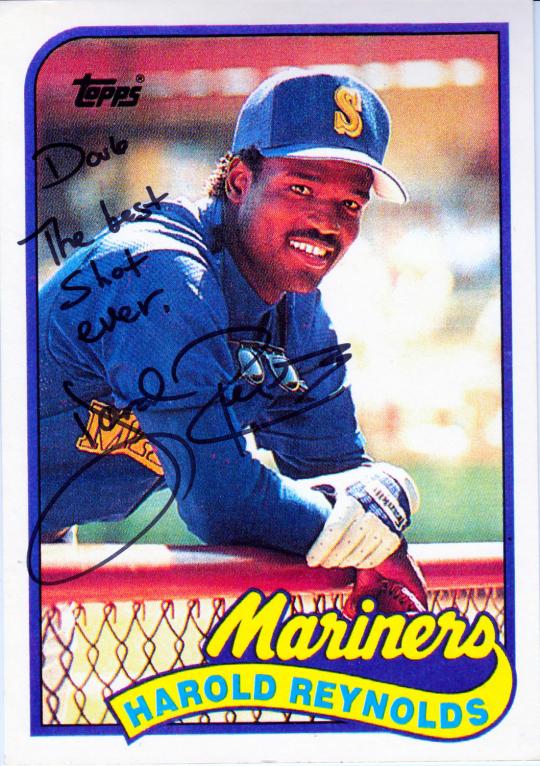

Asked for his favorite card in which he provided the image, McWilliams doesn’t hesitate to mention the 1989 Topps Harold Reynolds (No. 580).

“Harold was a wonderful friendly person. He took time to talk with me, and I think it shows in his expression,” McWilliams said. “I generally like a card because it is a good image or it has a good memory for me with the player. The Harold Reynolds card fits both those categories.”

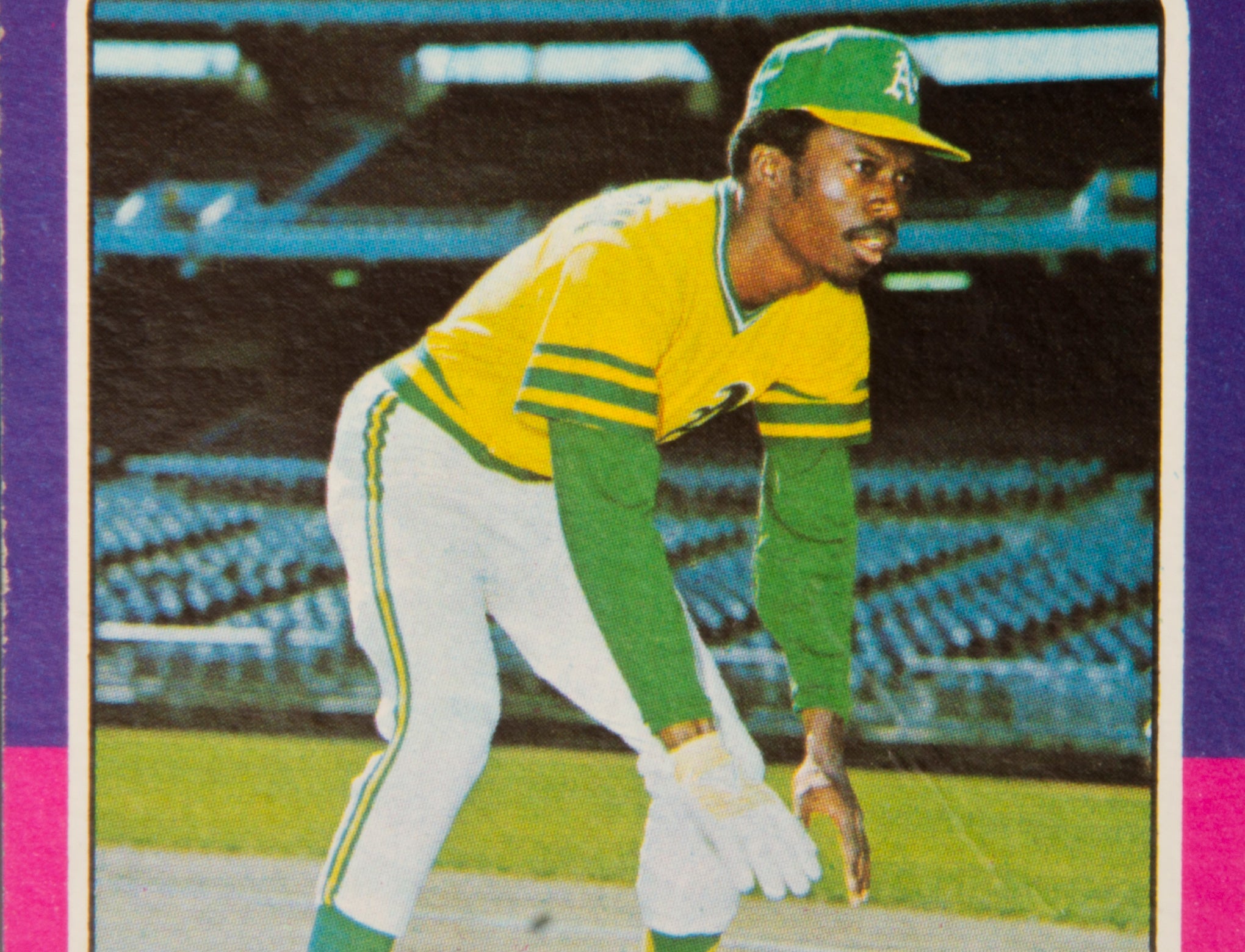

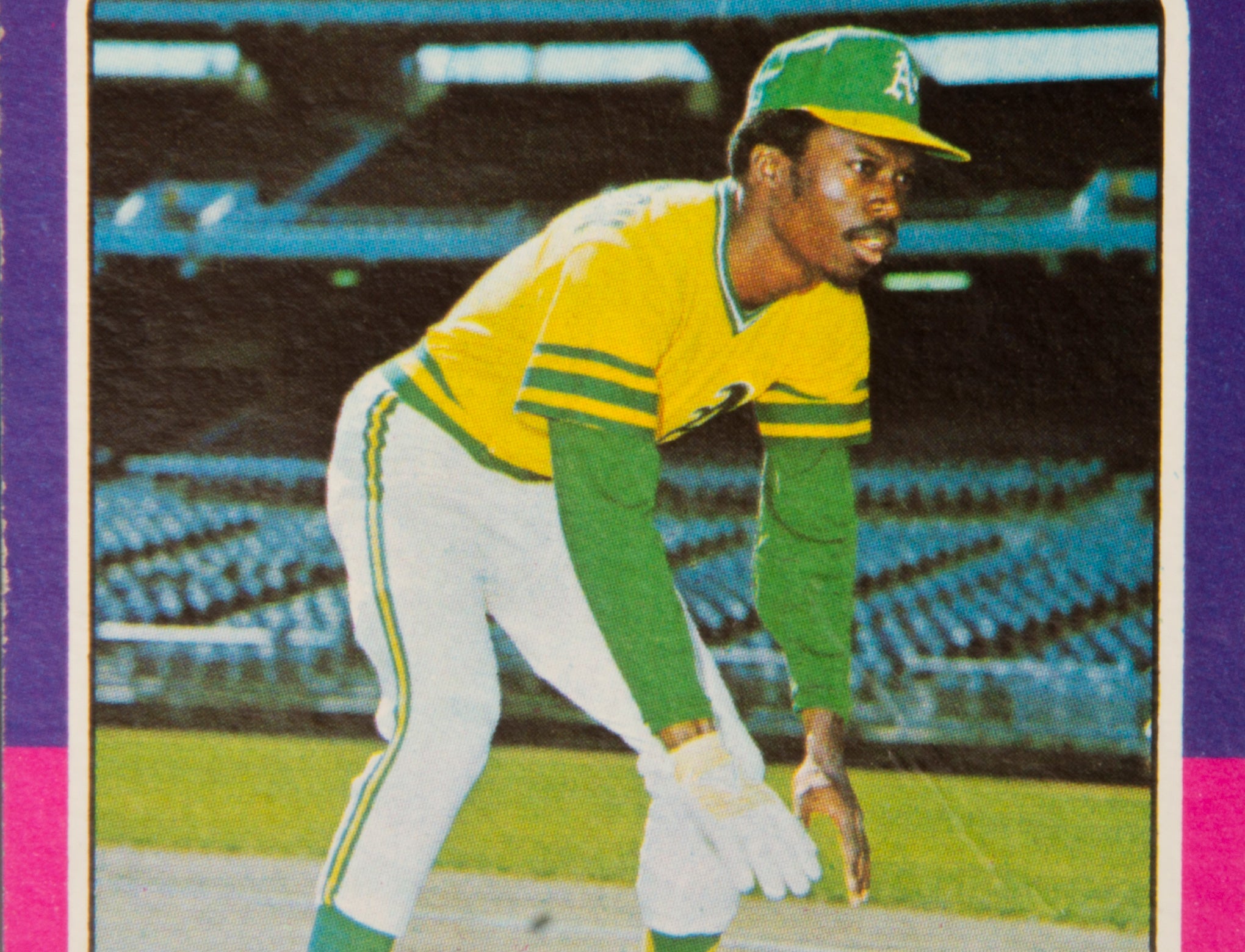

McWilliams also is sure to mention another favorite: The 1975 Topps Herb Washington (No. 407). “He was the first player who agreed to go out on the field – leading off first base for a stealing pose – mainly because no one was working out before the game.”

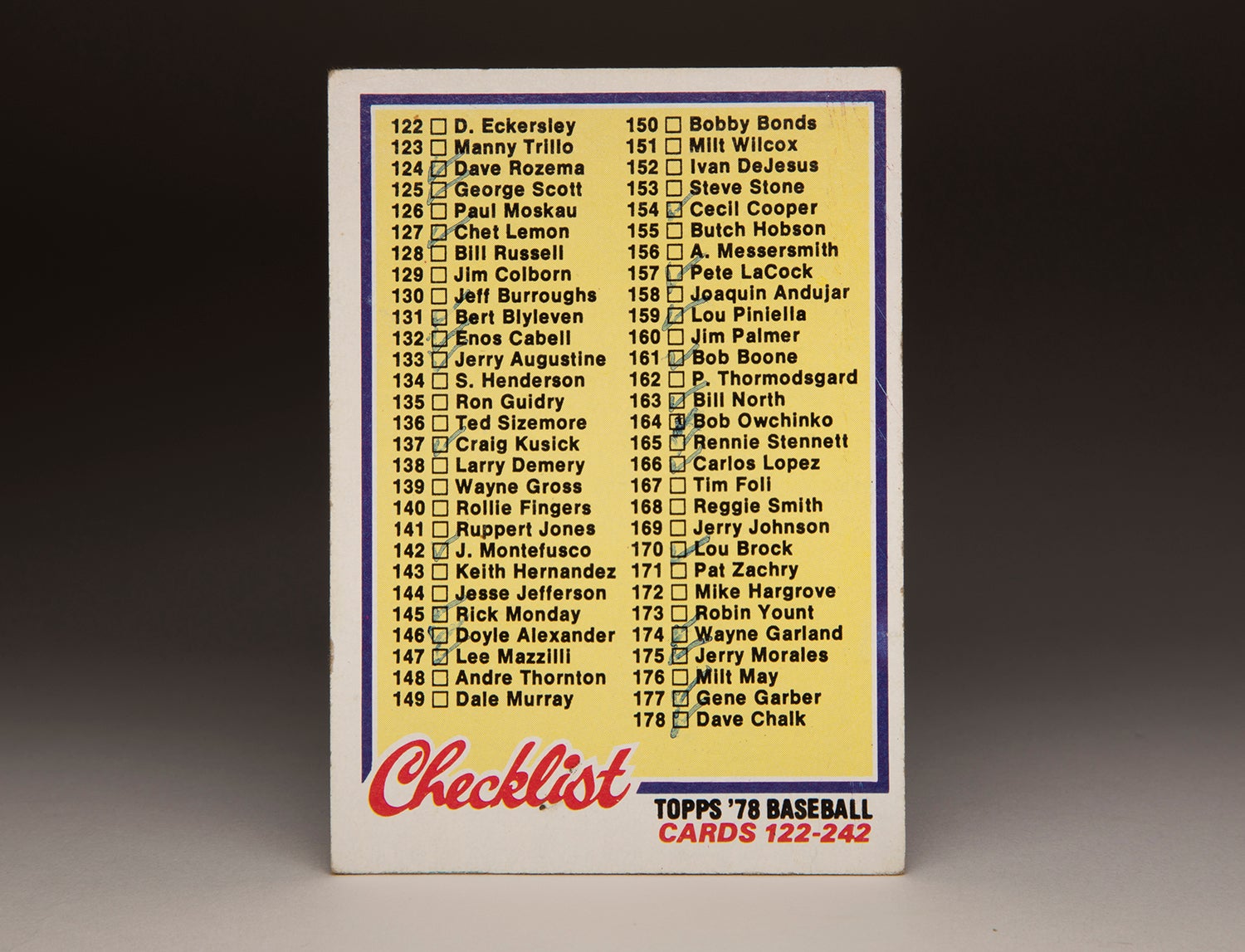

Others baseball cards McWilliams said he was proud to have provided the image for include, in no particular order: 1974 Topps Bert Campaneris (No. 155); 1975 Topps Gaylord Perry (No. 530); 1976 Topps Hank Aaron (No. 550); 1981 Topps Rollie Fingers (No. 229); 1982 Topps Joe Morgan (No. 754); 1982 Topps Bert Campaneris (No. 772); 1976 Topps Mickey Rivers (No. 85); 1976 Topps Dave Winfield (No. 160); 1976 Topps Robin Yount (No. 316); 1993 Bowman Dennis Eckersley (No. 485); 1993 Stadium Club (Topps) Andre Dawson (No. 810); 1987 Topps Rich Gossage (No. 380); 1975 Topps Harmon Killebrew (No. 640).

Looking back on his many successful years behind a camera viewfinder, McWilliams commented on the historic importance of his baseball images.

“Ozzie Sweet was a sports photographer that I admired and tried to emulate his technique,” McWilliams said. “I believe I succeeded maybe a dozen times, where if someone saw one of those images that I made they would say, ‘Ozzie Sweet shot that,’ even though I did it.”

Please consider making a gift today toward the Doug McWilliams Photograph Collection project to ensure these historic images are preserved for generations of fans to enjoy. Click here to learn more and make a donation.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Hall of Fame to Salute Fans’ Timeless Love of Baseball Cards in ‘Shoebox Treasures’

#CardCorner: An Interview with Doug McWilliams

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Herb Washington

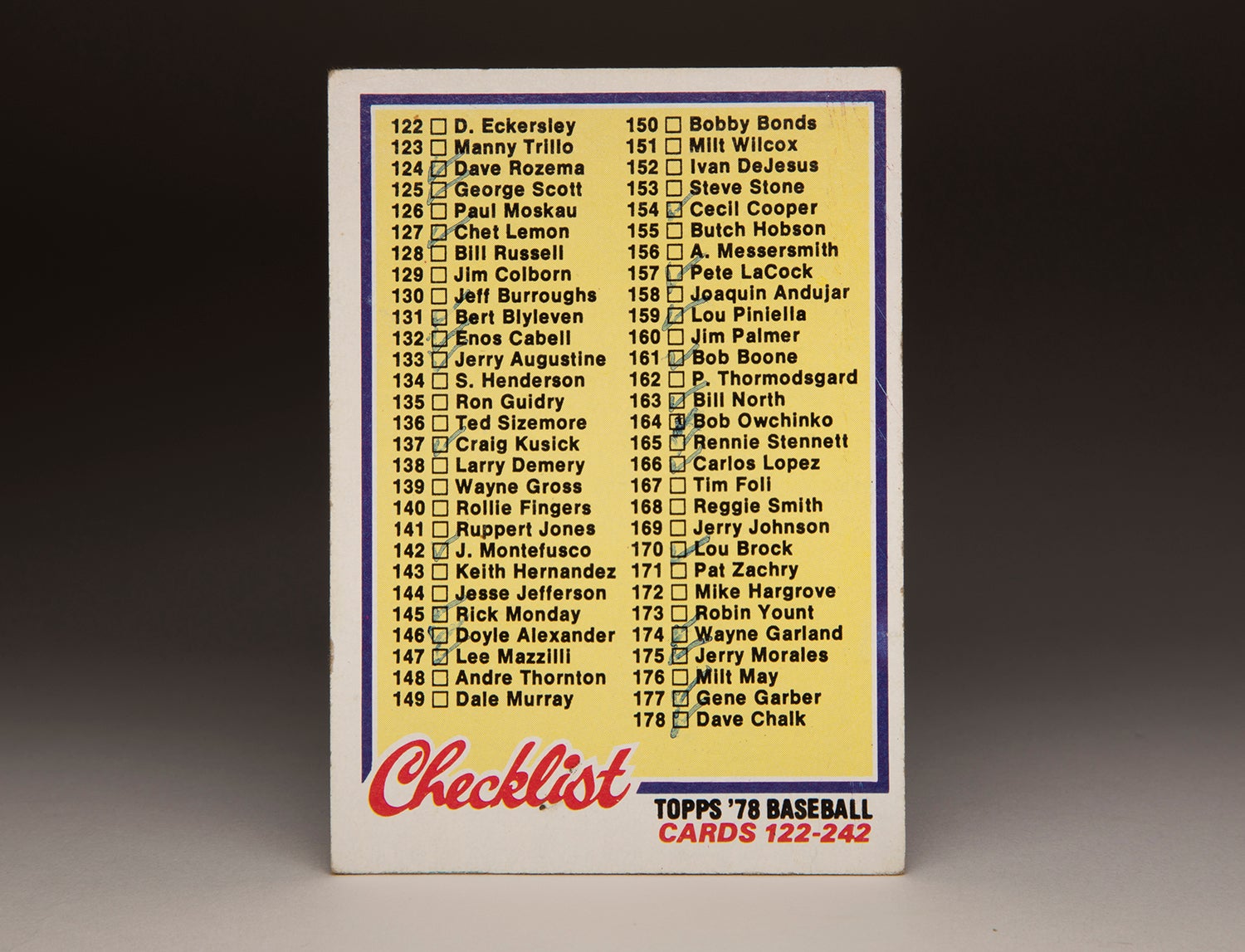

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Checklist

Hall of Fame to Salute Fans’ Timeless Love of Baseball Cards in ‘Shoebox Treasures’

#CardCorner: An Interview with Doug McWilliams

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Herb Washington