- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: An Interview with Doug McWilliams

#CardCorner: An Interview with Doug McWilliams

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

There have been a handful of giants in the baseball card industry over the years. In looking at the Topps Company alone, a few men stand out, including Sy Berger, a high-ranking executive who became the Father of the Modern Day Baseball Card. Another key player was Woody Gelman, the company’s art director and the artistic genius behind those early cards.

Then there is Doug McWilliams. From the early 1970s to 1995, McWilliams served as one of Topps’ photographers, becoming arguably the finest photographer of portrait and posed shots the company has ever seen. (A number of his card photographs have been featured in Card Corner.) In 2010, McWilliams traveled to Cooperstown to personally donate more than 10,000 negatives from his collection to the Hall of Fame’s Photo Archive. Mostly color shots, those negatives span the years that McWilliams worked for Topps, bringing to the Hall of Fame much of the game’s iconic photography from the 1970s, 80s, and 90s.

We talked to McWilliams about his career, including his trips to Spring Training, the friends that he made with the Oakland A’s, the obstacles that he faced, and the card photograph that he considers his favorite.

Bruce Markusen

Doug, I understand that famed photographer Ozzie Sweet was one of your major influences. Tell us more about Sweet and what you liked about his photography.

Doug McWilliams

My father was an avid amateur photographer, and gave me cameras early on. In 1948, when I was 10 years old, I discovered baseball. By listening to the games on the radio (games of the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League), receiving a subscription to Sport Magazine, and getting my first pack of baseball cards (the 1948 Bowman black-and-white cards), that did it for me.

Then I got a Signal Oil card of Ray Hamrick, also in 1948 - going to my first game ever, in Emeryville’s Oaks Park, and getting it signed soon after we got there. I was hooked for the rest of my life.

I was amazed by the portraits that Ozzie Sweet made, on a full page and in color, which came each month in Sport Magazine. And I wanted to do that when I grew up. Nice clean images that showed the players as attractive people that you wanted to know. I papered one wall of my bedroom, with those pictures - floor to ceiling. My Mom was very understanding.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

BM

Give us an overview of what you did for Topps. Where and when did your regular assignments take place?

DM

Initially I sold one image to Topps - of George Hendrick with the A’s in 1971. They didn’t use it. Then Sy Berger saw a postcard that I did of Vide Blue, and I was given a tryout in the spring of 1972, just from Sy seeing that one picture. I went down to Arizona after the regular Topps photographer had finished shooting. I was told to pick four teams and shoot pictures of the manager, all the players, and the coaches in camp, then process the film, identify the images, and send them in.

I was using a Mamiya RB67, which shot a transparency that was about the size of the finished card. It gave great quality. However, the printing process hadn’t caught up yet. That would happen in 1982, when Upper Deck came along with beautiful printing. For my trial session [in 1972], I shot the A’s, Giants, Cubs, and Brewers. I passed the test, and stayed for 23 years. I was mainly a Spring Training photographer, but as the years went on, and more images were needed, I shot everywhere on the West Coast and Arizona.

One year (1976) I was flown down to Dodger Stadium just to take pictures of one player. Bob Owchinko, a pitcher with the Padres. He was just out of college, and a whiz, so it was important to have him in next year’s set. They didn’t use what I shot that day. My first image of him came out in 1979 Topps (No. 488), which was shot at Yuma (Ariz.), during Spring Training.

Also for Topps, I shot the Golden State Warriors for one year, and the NFL for two years. I didn’t care for it, so I stayed with baseball exclusively. Basketball and football players have no time for themselves or photographers. Baseball players had lots of time, so I could get to know them, and they [could know] me. Which I enjoyed a lot.

BM

You mentioned that you first did a photograph for Topps in 1971, though it wasn’t used. That was also the year that Topps began using action cards in their sets. What were some of the difficulties that photographers faced in trying to come up with quality action shots in that era?

DM

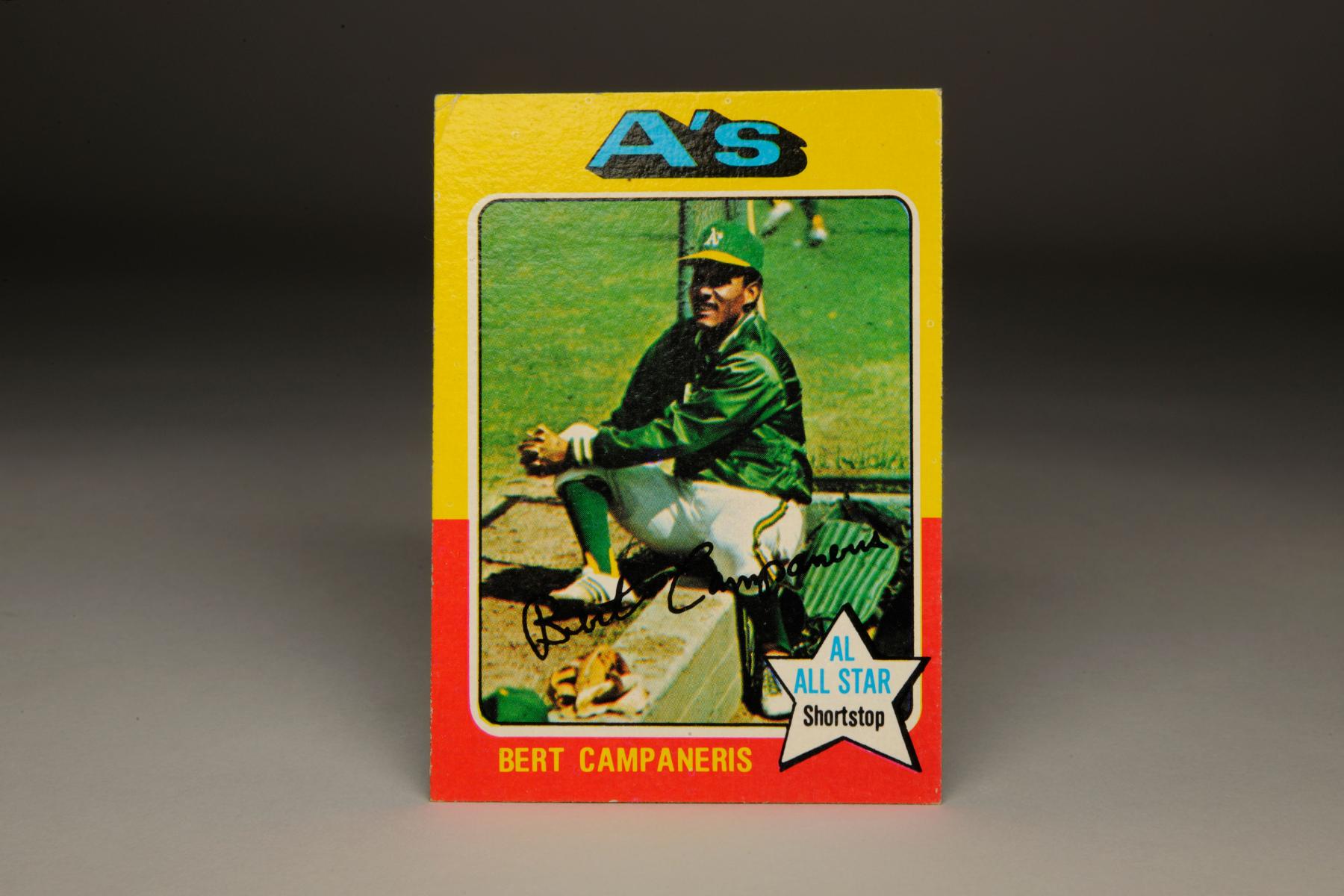

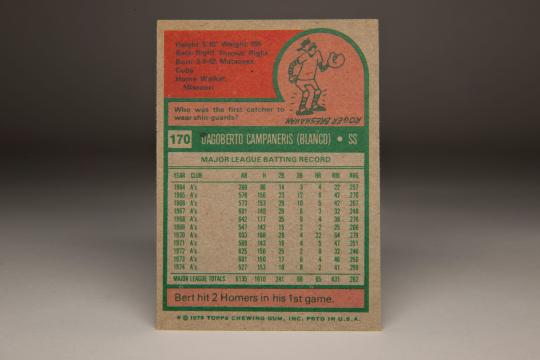

My first 35mm [action] shot used was a picture of Bert Campaneris sitting at the edge of the dugout. That was in 1975. Not much action, really just a candid shot. Topps required us to only shoot 100 ASA film [the speed of the film]. The lenses were not fast enough, nor long enough to do good work. That came later. The action shots used at first were not very good. My strong point was doing portraits and posed pictures of the players, and like Ozzie Sweet, I wanted them to look good. It was my strong suit.

One of the vice presidents at Topps once told me that no one shoots posed pictures better than me, and [as a result] I would always have a job with them. A few years later, I never heard from them again. I worked on a yearly retainer, one year at a time. Never knew if I was working the coming season, until they called me in January.

I had to assume I was [getting the call], as the setup took a long time, what with cleaning cameras, lenses, obtaining film, and getting rosters, etc. Not to mention figuring out the itinerary and the schedule of games and where I was staying. I started that work here at home in December. They didn’t realize how much work it was, and is.

BM

What did you like better, photographing spring training in Arizona, or regular season games in the Bay Area?

DM

I loved going to Spring Training in Arizona. Beautiful weather, the sun was out most mornings. Maybe one day was lost to rain, but only once in a while. I was the only baseball card photographer there for 10 years. Fleer and Donruss began to show up in 1981. Both those photographers became good friends of mine, over the years. There is a nice picture of the three of us, in the article about me in the Hall of Fame’s Memories and Dreams (Summer, 2010 - Vol.32, No. 3, page 29)

Shooting at ballparks started in earnest for me when Topps added small [inset] portraits to the front of the cards in 1983 and ‘84. In the beginning I went to spring training for only a week; by the time I was finished [with Topps] it was for three weeks, usually. I spent a year of my life in Arizona in February and March, if you add them all up.

BM

As someone who did a lot of his work at the Oakland Alameda County Coliseum, I imagine there were some players on the A’s who became favorites of yours to work with? Who were they, and why did you like them?

DM

Many of the A’s became good friends: Reggie [Jackson], Joe Rudi, Jim Todd, Paul Lindblad, Alfredo Griffin, and on and on. You just hit it off with people, for no particular reason. Some I'm still in touch with, like Ray Fosse, Vida Blue, and Ted Kubiak. I also became friends with players from other teams, like Ken Brett and Sid Monge and Jerry Reuss. I also got to know many of the clubhouse men.

BM

Billy Martin, rather infamously, once made an obscene gesture toward a Topps photographer. Did you have any difficult experiences along the way in trying to get players to pose for you?

DM

Billy Martin was no problem for me. He didn’t know me, but we both went to Berkeley High School, nine years apart. I’ve known his sister Pat, well the past five or six years.

I could count [the difficult players] on one hand. But I don’t care to mention names.

One had trouble with the race of the owners of my company being Jewish. A terrible rant! Right in front of me and [pitcher] Paul Lindblad, who told him to knock it off! I saw [the unnamed player] later in Yuma, and he came and apologized to me. I still don’t accept it, nor believe him.

One player was so impressed with himself, it was ridiculous to see. I could not believe how rude he was to media folks - even with his father, a former player, standing nearby.

And two players, when they got their time in, and received their first million dollar salaries, made like they didn’t even know me. Earlier, one of them was so ecstatic when he found out I was the Topps photographer. It was his first year up, and he could hardly stand it; he became a friend on a first-name basis for four years or so, then the big money really changed him. Sad! I never shot his picture again for Topps.

Goodness, I guess I have shown my colors. Sorry about that. But only four or five out of thousands. Not bad!

BM

Typically, when you took photographs of a player in Spring Training, how many photos of each player would you submit to Topps? Did you have any input on which photo would be used in the new card set?

DM

I was required to take six posed images of each player at camp: two head-and- shoulders, two from the waist up with the player posed and kneeling, and two full-length posed of the player kneeling or standing. I had no input as to what was used. Just what the poses were. That was Butch Jacobs’ job at Topps; he was an editor. After the film was processed, or later sent to a lab in New York City undeveloped, I was finished. I only worked three to maybe five weeks a year.

Tony Gwynn was just furious with his rookie Topps card, when he saw me later. I had to agree! The past five or 10 years Topps has been issuing old cards in the former formats, and they have done three more of Tony, that were shot at, or near the same time, and they are really nice images. It was all the editor’s choice. Although I shot it, it wouldn’t be my choice.

In the mid-1980s, almost all shooting went heavy with 35mm cameras, and long lenses. I was required to shoot 15 rolls of 36 exposure film (still 100 ASA film), so that gave them 540 more pictures to use, although not all were usable.

BM

Topps photographers regularly used to take photographs of players without their caps, or with their caps turned upward so as hide the logo. This made it easier for Topps to adjust when a player changed teams. Did you do this with all players, or only with players who were more likely to change from team to team?

DM

I was never asked to do that. I think that went out maybe my first year in 1972. I did have an assignment to do Matty Alou and Dal Maxvill late in 1972 with the A’s, and when the cards came out, Matty was wearing a Yankees uniform, badly airbrushed. They had sent me some cards during that winter, to show me some samples of what my cards would look like, as it was my first year shooting for them, with no printing on the back side. One was of Matty Alou, in an A’s uniform. I think it has a good dollar value.

BM

Did you ever have a case of mistaken identity, where you photographed a player and thought that it was someone else entirely?

DM

Fortunately I never made that mistake. I had a very good set routine to keep everyone in order and correctly identified. And it worked well. The editor made one dandy mistake with a rookie player who I had known for about four years,Jeff Cox. I made a habit of shooting Pacific Coast League and California League teams, so the players would know me when and if they finally arrived. I had shot Jeff with Vancouver, Modesto, San Jose, and at A’s Spring Training, so he was very excited to make the A’s one year and finally have a card. Well, when his card came out, the picture was actually Steve McCatty. I made some custom cards for Jeff, to give to his family to make up for the mistake.

Some of the players tried to play tricks on the photographers, but I was too old and wise, I guess. I was 35 when I started with Topps. Many of the photographers were a bit green behind the ears. A favorite trick was to stick a match in your shoe while you were busy shooting, so you wouldn’t notice - and then light it. Always good for a laugh! Ha ha. You have to remember that many of the players were really still kids!

Another favorite trick was to yell out to you as you passed the dugout, that you had dropped something. Hoping that you would come back and look everywhere. One day I saw them doing this to some new guys. So before I got there, I put a $5 bill in my hand, and when they yelled at me, I turned around, and reached down and pretended to pick up the bill. I got the last laugh, and a good hurrah from the players all around.

BM

Sometimes Topps airbrushed different colors onto existing photographs, often with mixed results. How did you feel about that?

DM

I thought it looked awful, as far as I was concerned. They just didn’t have a very good airbrush artist. It can be done well. But there is no need for airbrushing these days with Photoshop and computers.

BM

Is there a particular Topps card that you shot that you’re most proud of, or perhaps you feel is best emblematic of your work?

DM

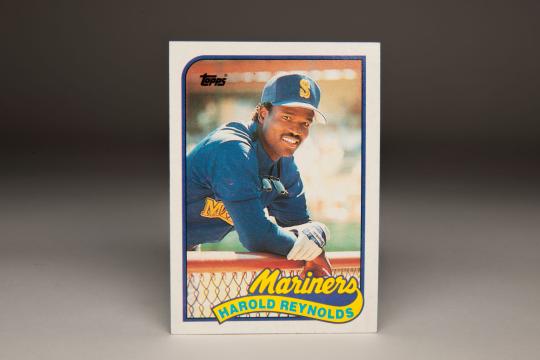

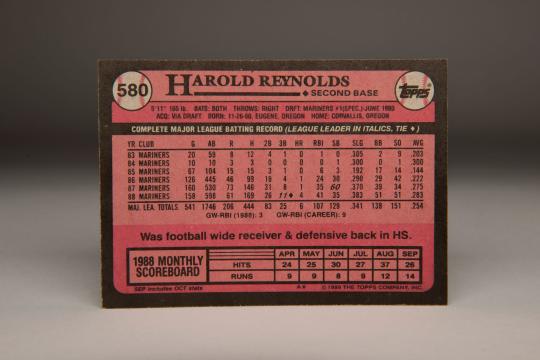

Yes! I think the card that pleases me the most is one I did of Harold Reynolds, while he was with Seattle, for his 1989 Topps card. He told me that it was the best card ever made of him. He was and is a wonderful person. I admire him very much, and enjoy still seeing him on TV. One day he talked with me about half an hour at Spring Training. It was marvelous experience for me. His father was a minister up in Corvallis, Ore.

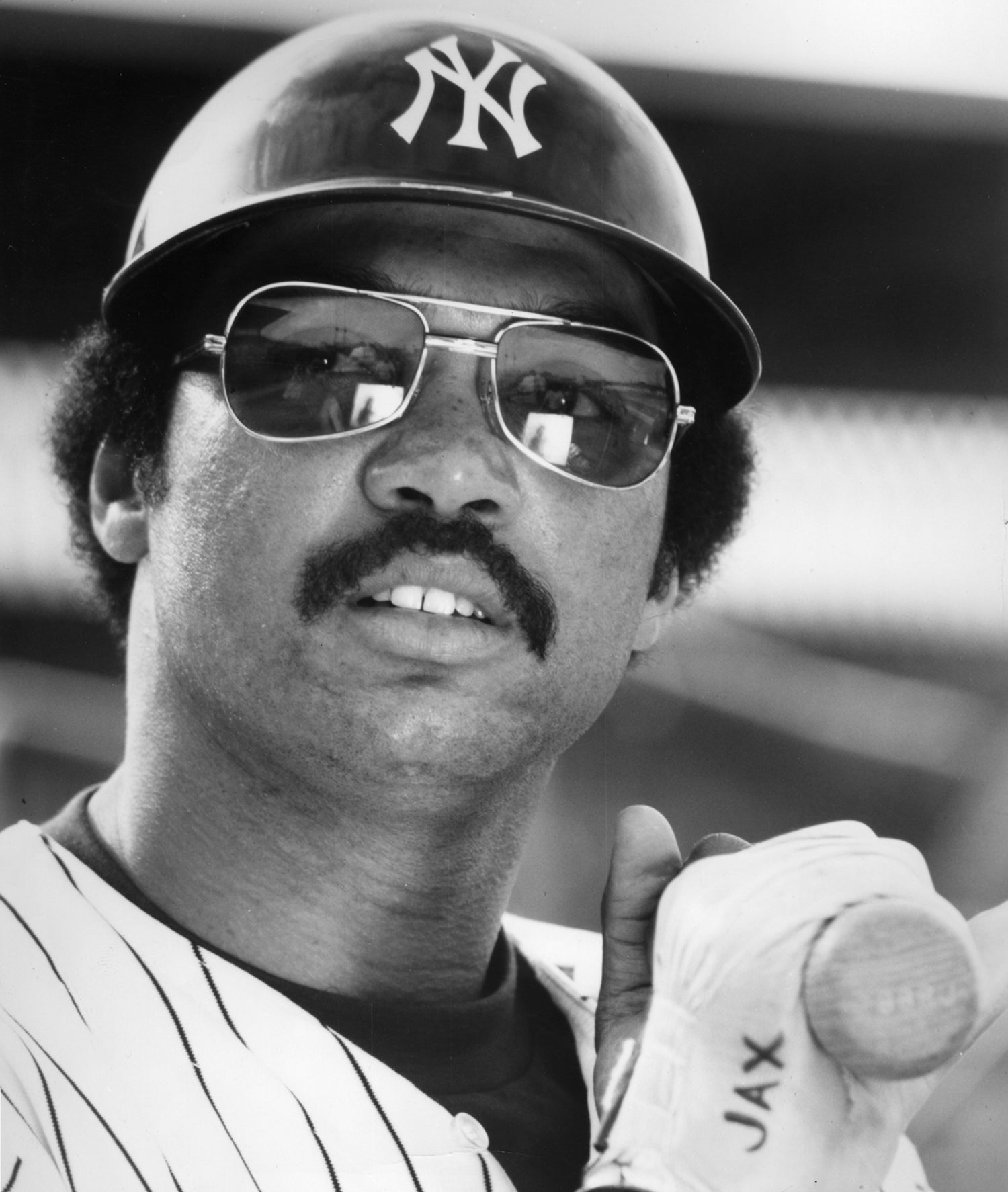

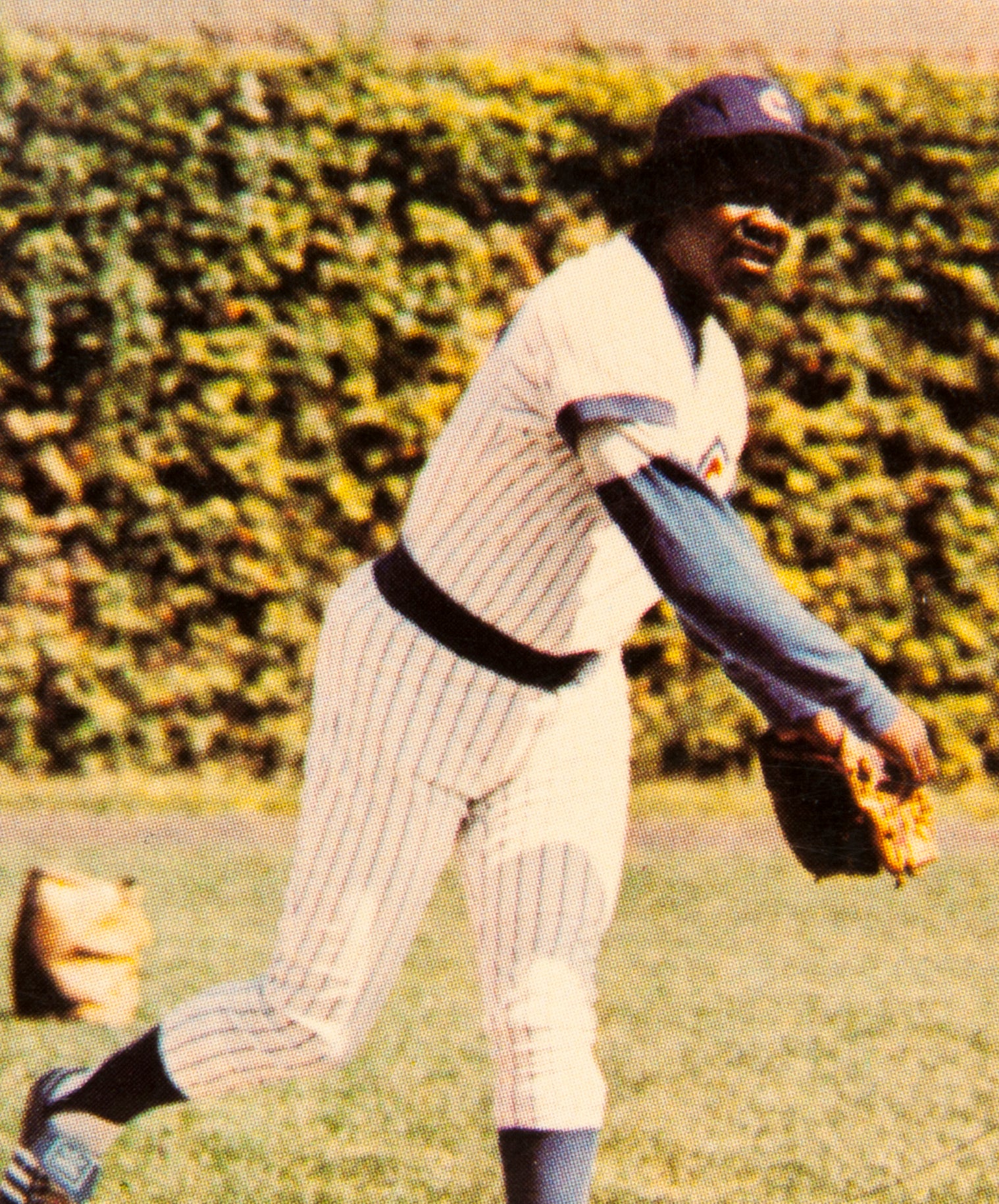

I've shot thousands of baseball cards, though I’ve never actually counted them, but a few others I like are Herb Washington (1975 Topps), Lloyd McClendon with the Cubs (1989 Bowman), Benito Santiago with the Padres (1988 Topps), Billy Martin with the A’s (1983 Topps), Mike Norris (2005 Topps Fan Favorite) and Reggie Jackson with the A’s (1987 Mother’s Cookies).

BM

As a Topps photographer for so many years, what would you like your legacy to be?

DM

That I loved the game, and the folks connected to the game, and derived much pleasure making them happy with the results of my work, while making them look good.

Pat Kelly, formerly the head the Hall of Fame’s Photo Archive, told me while I was there delivering my life’s work, that it appeared to her that everyone I photographed knew me. That is what I strived for, and to have her say that to me, was wonderful to hear. I realized that I had succeeded.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

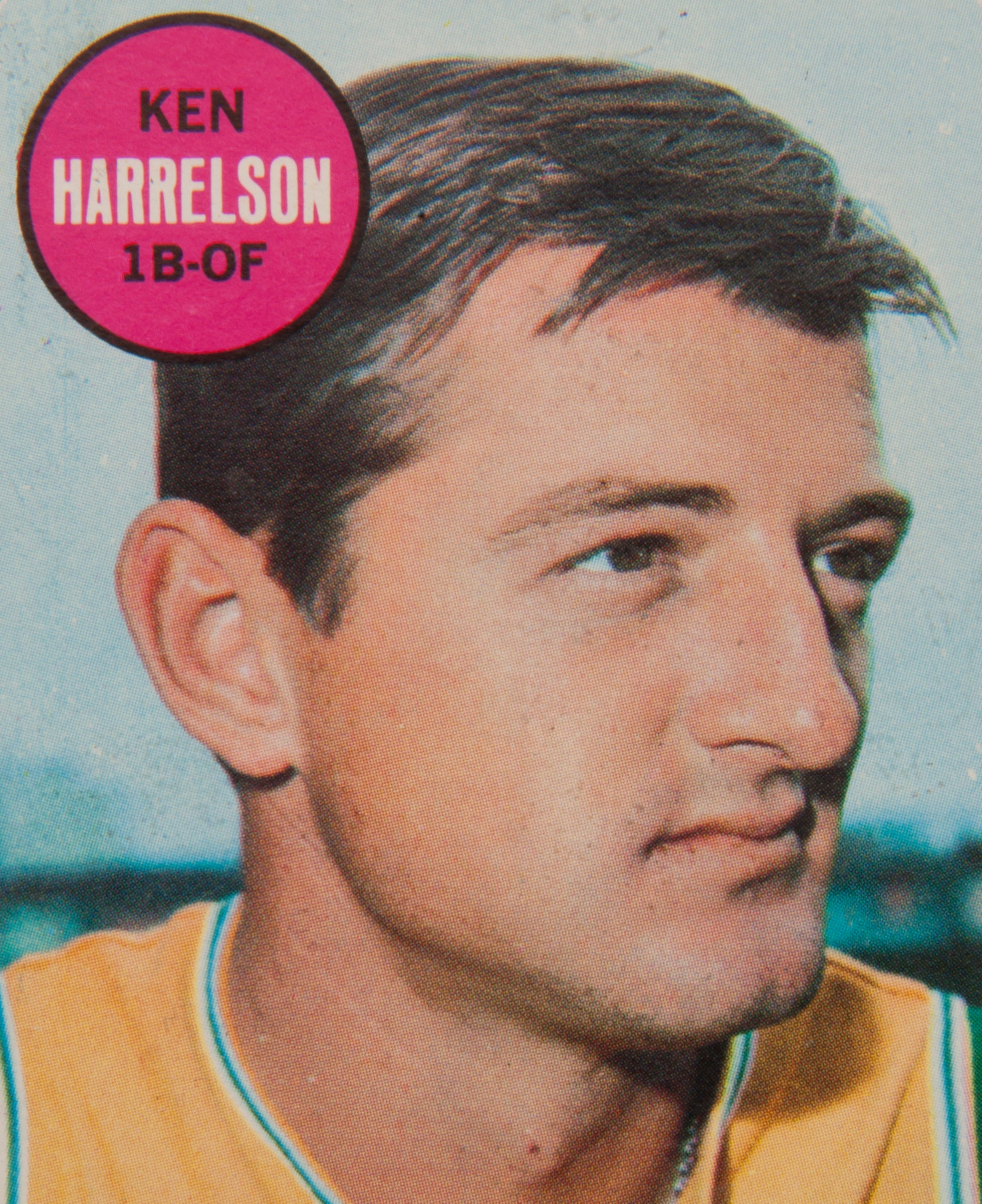

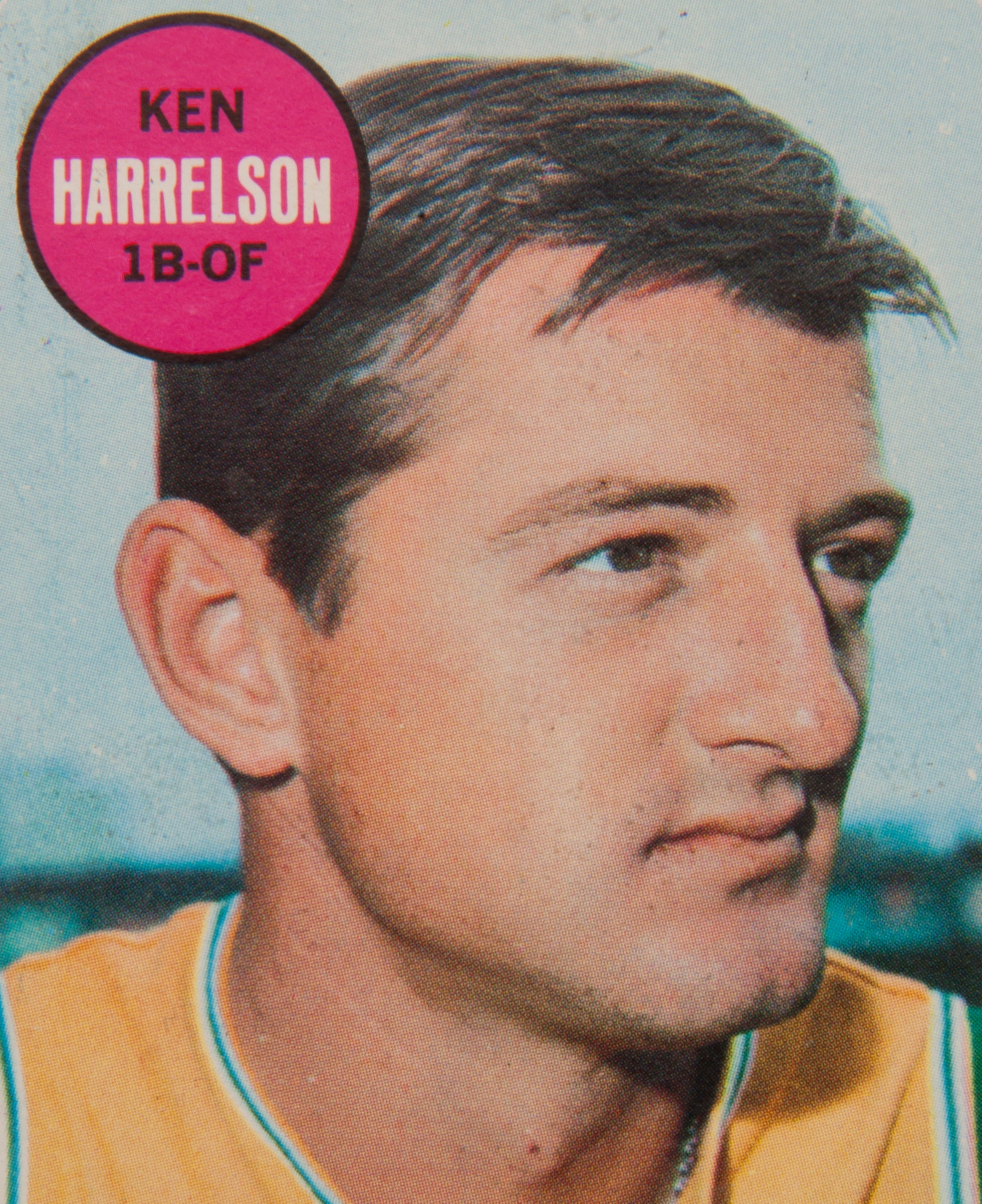

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Hawk Harrelson

#CardCorner: 1981 Fleer Lynn McGlothen

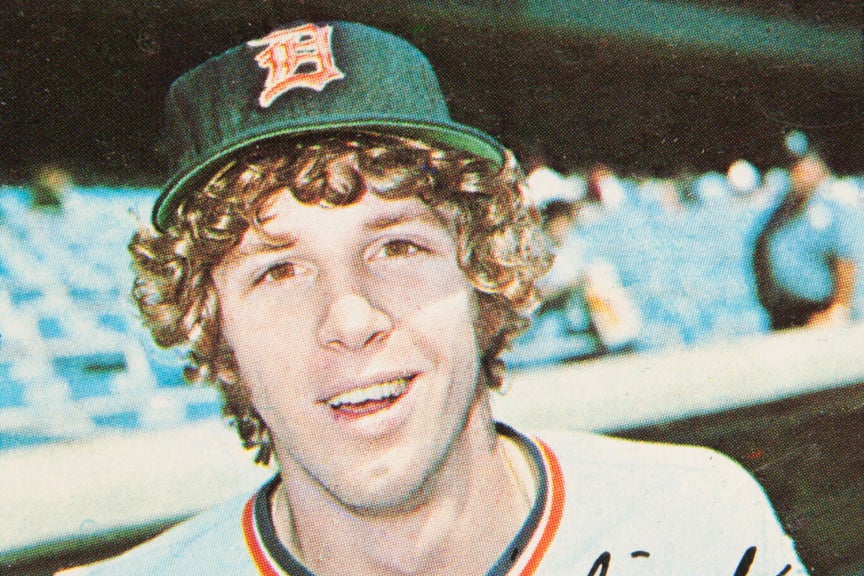

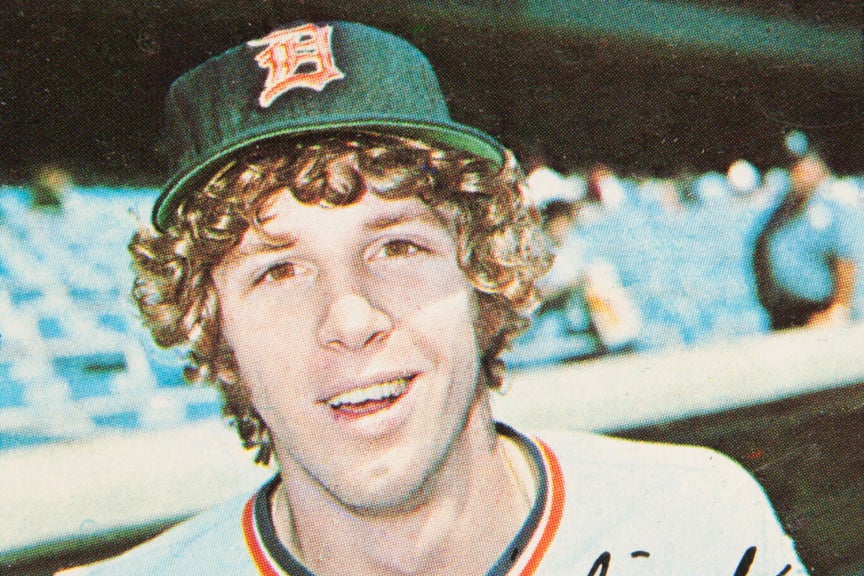

#CardCorner: 1977 Topps Mark Fidrych

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Hawk Harrelson

#CardCorner: 1981 Fleer Lynn McGlothen