- Home

- Our Stories

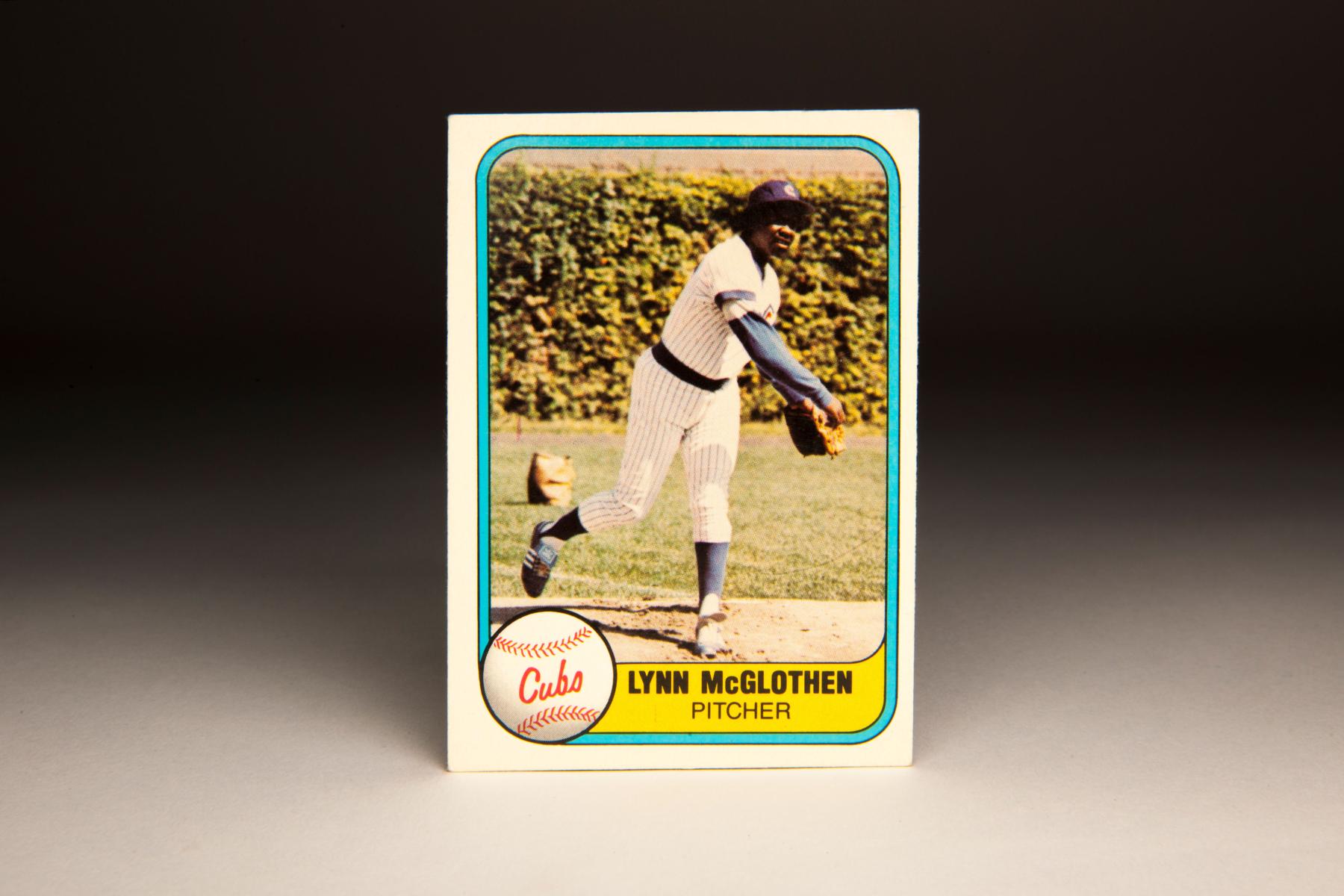

- #CardCorner: 1981 Fleer Lynn McGlothen

#CardCorner: 1981 Fleer Lynn McGlothen

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

As I look back at my own personal history of collecting baseball cards, two years stand out above all of the others. The first was 1972, the year that I started collecting, picking up Dave Cash and a few other cardboard goodies from Pickwick’s Stationery Store. The second year was 1981. That was the year when the landscape of collecting changed - and for the better. For the first time in my young lifetime, more than just one company was producing a full set of baseball cards. For years, it had been Topps and only Topps. Now, two other companies entered the fray, as Donruss and Fleer came out with inaugural sets that would challenge the established kings of the industry at Topps.

For more than 20 years, Topps had owned the monopoly on baseball cards through the exclusive contracts the company negotiated with major league and minor league players. An indication of a coming change occurred in 1975, when the Fleer Company filed a lawsuit against Topps and the Major League Baseball Players’ union, contending that the monopoly was illegal. It took a while, five years in total, but the courts eventually ruled in Fleer’s favor. According to the 1980 decision, Topps could no longer have exclusive long-term rights to baseball players’ images. The court ruled that the union would have to allow at least one other company to produce cards by 1981.

In 1981, two companies joined Topps in the changed marketplace. Fleer and Donruss reached agreements with the Players’ Association to produce full sets of cards. Once those sets made their ways into stores, the Topps monopoly had come to an official end, some 25 years after it began.

Due to their relative inexperience with cards (Fleer, for example, hadn’t produced baseball cards since the early 1960s), and the short time frame given to produce a set for the 1981 season, Donruss and Fleer experienced growing pains. The Donruss set was full of out-of-focus photography, a number of misidentified players, and a slew of typographical errors on both the front and back of the cards.

Fleer also made some mistakes, particularly in terms of typos and proofreading, but the design of their cards, with a firm colored frame and a baseball neatly tucked into the lower-left corner, was more striking and more polished than Donruss. Fleer’s photography, while lacking in excitement, generally featured crispness that was better than Donruss’ initial offering. It’s a good set from Fleer - a very solid first effort from a company re-entering the field of baseball cards for the first time in roughly 20 years.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

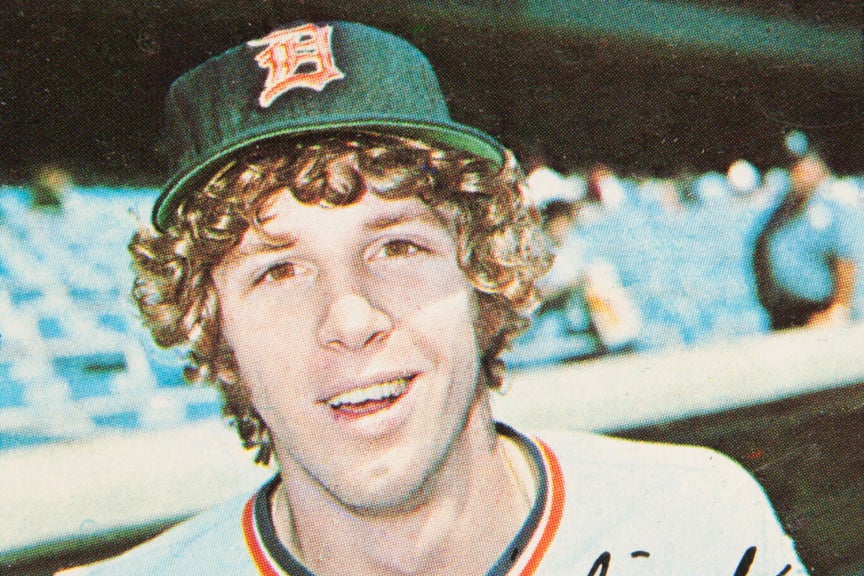

Among my favorites in the set is this card, one that features a player who has become mostly forgotten. It’s a card for journeyman right-hander Lynn McGlothen, a once-promising pitcher with the Boston Red Sox who found himself struggling in the early 1980s and would soon become one of the game’s tragic figures.

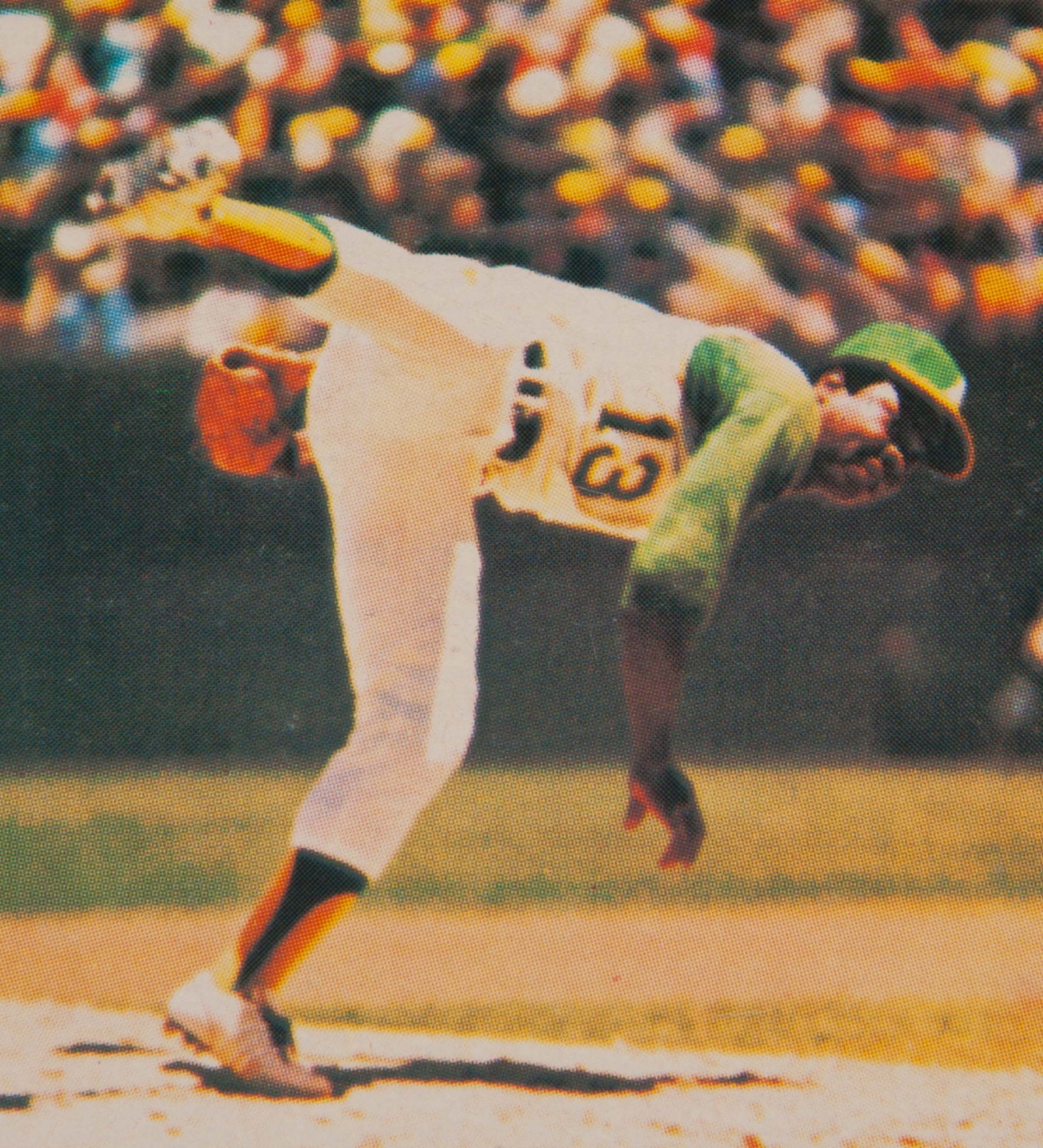

The McGlothen card has several attractive features, beginning with the beautiful home uniform of the Chicago Cubs. That uniform has changed somewhat since then, but it’s very similar to what the team wears today, and it remains an iconic uniform - attractive, distinctive, and dignified. Second, the photo was taken at Wrigley Field, a venue that makes almost any baseball card look more appealing and inviting. We can see the outfield ivy in full blossom behind McGlothen, an indication that this shot was taken somewhere in the middle of the summer, sometime during the 1980 regular season.

Fleer also gives us something unusual here. Rather than show McGlothen during game action, or in one of those contrived sideline poses, Fleer has opted for a photo of McGlothen warming up in the Wrigley Field bullpen. It’s something different, something refreshing. Another note of interest is the large brown bag that can be seen behind McGlothen in left field. Some collectors have jokingly referred to the bag as a “potato sack,” but it’s likely nothing more than a ball bag, a standard piece of equipment seen during pregame workouts. With the ball bag in full view, and in fair territory, it becomes obvious that McGlothen is throwing pitches during a pregame or off-day workout at Wrigley, and not in the middle of an actual game.

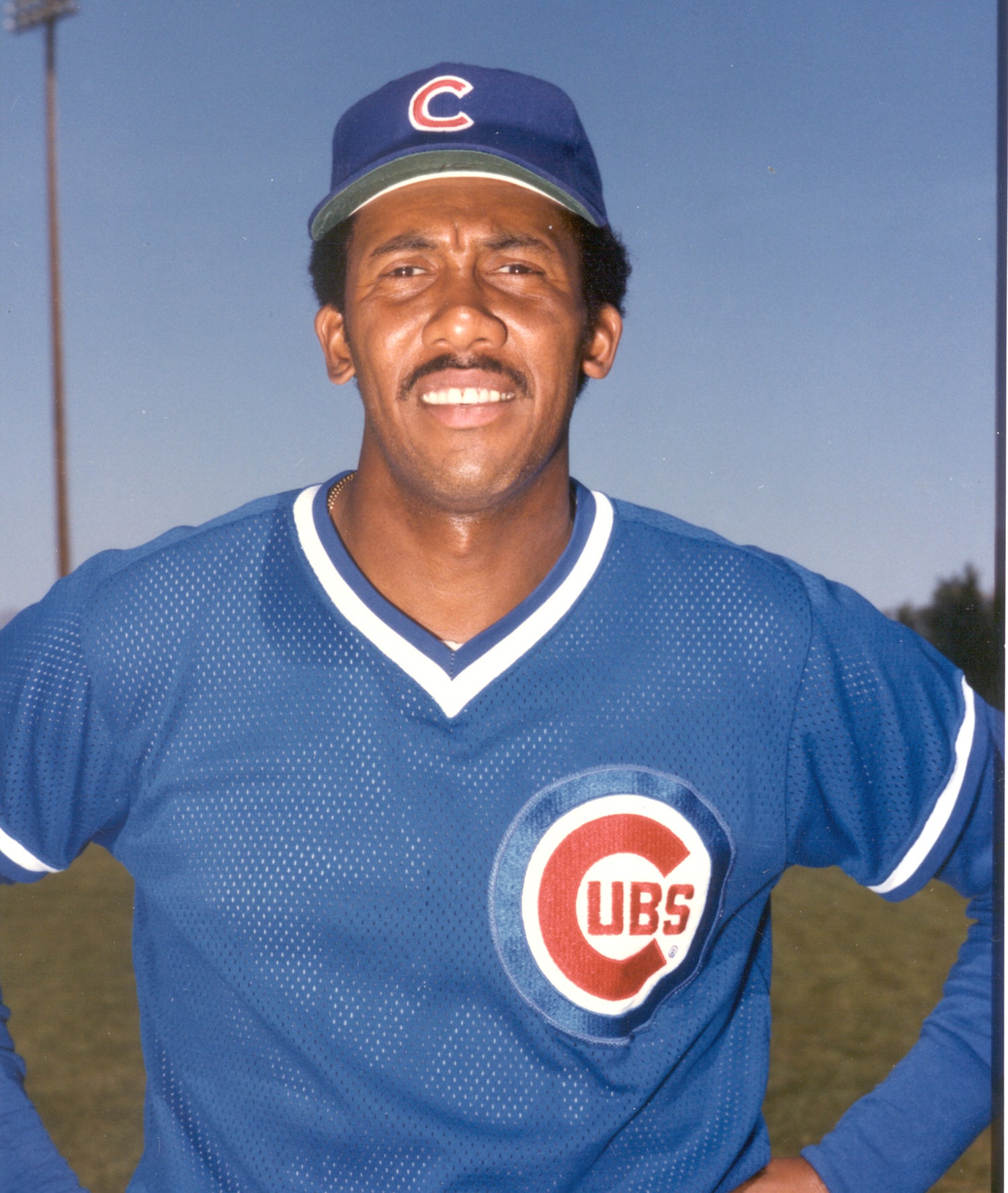

The card offers lots of fertile subject matter, as does the career of the pitcher himself. Who exactly was Lynn McGlothen? He was drafted out of Grambling University, one of the top African-American colleges in the country, and promoted to the big leagues by the Boston Red Sox in the middle of the 1972 season. Featuring a hard fastball that regularly hit the mid-90s, McGlothen showed promise by striking out 112 batters in 145 innings. But after struggling for the Sox in his sophomore season and enduring a demotion to Triple-A Pawtucket, McGlothen soon encountered a change in venue. After the season, the Red Sox sent him and left-hander John Curtis to the St. Louis Cardinals for two right-handers, Reggie Cleveland and Diego Segui.

McGlothen responded well to the deal. He was never better than in his Cardinals debut season of 1974, when he used his live fastball and big overhand curve ball to win 16 games, post an ERA of 2.69, make the National League All-Star team, and earn consideration in both the Cy Young and MVP Award voting. On a staff that featured an aging Bob Gibson and a young Bob Forsch, one could have made the argument that McGlothen was the true ace. The Cardinals regarded McGlothen as a young Gibson, in part because of the quick way in which he liked to work on the mound. As McGlothen told Cardinals beat writer Neal Russo for the Sporting News, “I once pitched a nine-inning game in an hour and 40 minutes.” Baseball could use a few Lynn McGlothens nowadays.

As a young fan at the time, I remember a couple of checklist items about McGlothen. Fans always used to pronounce his name incorrectly, saying it as Mc-Gloth-len, adding an “L” to the last syllable. Sometimes fans looking at box scores would confuse Lynn McGlothen with Jim McGlothlin, another right-handed pitcher from the era. McGlothlin was an Irish reliever nicknamed “Red” who became somewhat notable for appearing in both the 1970 and ’72 World Series. Sadly, he would also become one of the game’s tragic stories, succumbing to leukemia in 1975 at the age of 32.

Lynn McGlothen was also easy to remember because he was one of the few African-American starting pitchers at the time. Most African-American players tended to be pushed toward the “speed” positions on the diamond - the outfield, second base, and shortstop; very few found their way to the major leagues as pitchers. There were a handful - like McGlothen, Gibson, Ray Burris, Don Wilson, Ferguson Jenkins, Blue Moon Odom, Jim Bibby, Rudy May, and Vida Blue - but they tended to be the exceptions in a game where most pitchers were white.

McGlothen and Bibby stood out from the other black pitchers because of their size. All of the other aforementioned pitchers were lean and athletic; McGlothen was always pudgy, always about 10 to 15 pounds overweight. He took some criticism because of that, but continued to pitch well. In 1975 and ‘76, McGlothen put up solid numbers, though not at the level of his 1974 season. Still, he logged over 200 innings each summer, kept his ERA under 4.00, and won a combined 28 games. He also caused some controversy in 1976 when he hit two members of the New York Mets, Del Unser and Jon Matlack, with inside pitches and then admitted that he had done so on purpose. National League president Chub Feeney was not impressed by McGlothen’s honesty. He suspended the right-hander for five days and hit him with a $300 fine.

As foolish as McGlothen had been during that incident, it probably had little influence on a decision the Cardinals would make that winter. After the 1976 season, the Cardinals decided to part ways with their talented young right-hander, sending him to the San Francisco Giants so that they could reacquire third baseman Ken Reitz. On the surface, it seemed like a questionable trade for the Cardinals.

Reitz had played for St. Louis only one year earlier, before being traded to San Francisco for left-handed pitcher Pete Falcone. Reitz was an excellent defensive third baseman, but he lacked much of an offensive profile and couldn’t run at all, making him an odd fit on the artificial turf at Busch Memorial Stadium.

As it turned out, McGlothen would flop in San Francisco. Unfortunately for McGlothen, the toll of pitching more than 670 innings in three years for the Cardinals seemed to take a toll on his right arm. Sidelined by a bad shoulder for a good portion of the 1977 season, McGlothen saw his pitching performance crater, as he won only two of 11 decisions.

McGlothen finished the season in the bullpen, his ERA settling at 5.63. The situation only worsened in 1978. After a poor start to the new season, the Giants rarely used him out of the bullpen. At one point, McGlothen didn’t pitch for a solid month. Finally, at the June 15 trading deadline, the Giants peddled him to the Cubs for outfielder/third baseman Hector Cruz.

Although McGlothen struggled for the Giants, he was a popular player with both teammates and opponents, just as he had been in St. Louis. “He was a big hit in St. Louis and San Francisco, had that good personality, smiled a lot, and loved the fans,” says John D’Acquisto, who also pitched for the Cardinals and the Giants in the 1970s, but not at the same time as McGlothen. “He was a character, smiled a lot, left a good presence around the team.” On the field, McGlothen remained determined, even when he struggled. “I pitched against him a few times,” says D’Acquisto. “He was a fierce competitor.”

McGlothen took his upbeat attitude and competitive streak to Chicago, where he resurrected his career. Regaining some of his arm strength with the Cubs. McGlothen pitched well in relief and then moved into the rotation in the spring of 1979. At roughly that same time, our house obtained cable television, expanding our channel capacity from five stations to more than 50 and allowing me to watch many afternoon Cubs on WGN. I became quite familiar with the work of McGlothen, who delivered two solid seasons for the Cubs, winning 25 games.

McGlothen couldn’t sustain the success. He struggled with elbow trouble in 1981, resulting in a midseason trade to the cross-town Chicago White Sox. After a tough time on the South Side, the injury-plagued veteran drew his release and pitched briefly for the New York Yankees, but his time in the Bronx did not go well. After getting raked in two relief outings, the Yankees placed him on the disabled list with a broken finger, brought him back in September, and then released him. I followed the Yankees avidly at the time but must confess as to having almost no recollection of McGlothen pitching in pinstripes.

McGlothen’s stopover in New York would turn out to be his last in the major leagues. No one could have known what would happen only two years later, and only three years after his Fleer card came out. It was the summer of 1984. McGlothen was visiting a friend in a mobile home in Louisiana, when it went up in flames. The woman who was living there, Gloria Smith Reed, succeeded in saving her two children from the fire, but when she returned to help McGlothen, they were both overcome by smoke inhalation. Both died in the accident; McGlothen, who was found lying face down with his hand over his mouth, was just 34.

No one seems sure how the fire started. Authorities at the time did rule out any possibility of foul play. The fire appeared to have been an accident, or simply a case of bad luck.

There is relatively little information about McGlothen’s passing. Sadly, his death received such little attention that I didn’t learn about it until years after the fact. There is still a degree of mystery to his death, given that the cause of the fire remains unknown.

I wish I had a happier ending for Lynn McGlothen, who seemed to be a happy-go-lucky fellow and whose 1981 Fleer card brings back such good memories for me.

Sometimes life doesn’t cooperate with our fanciful game.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

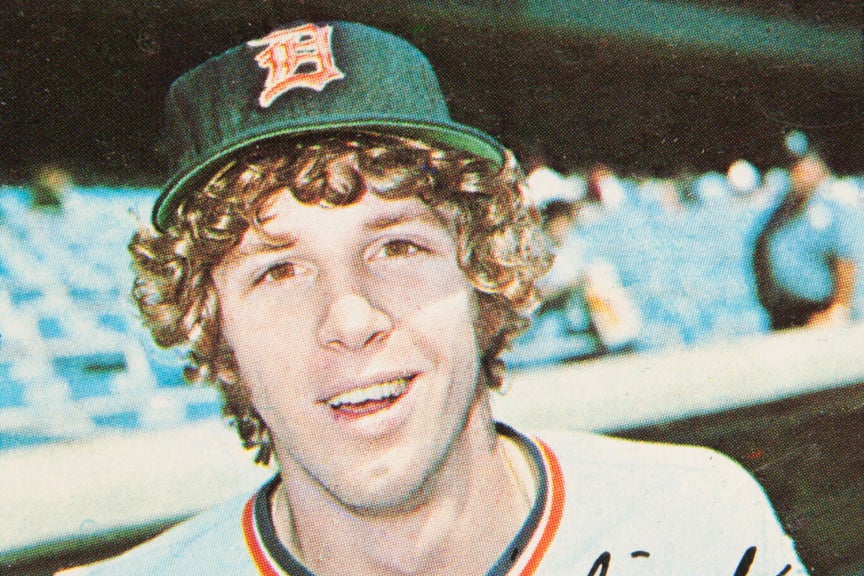

#CardCorner: 1977 Topps Mark Fidrych

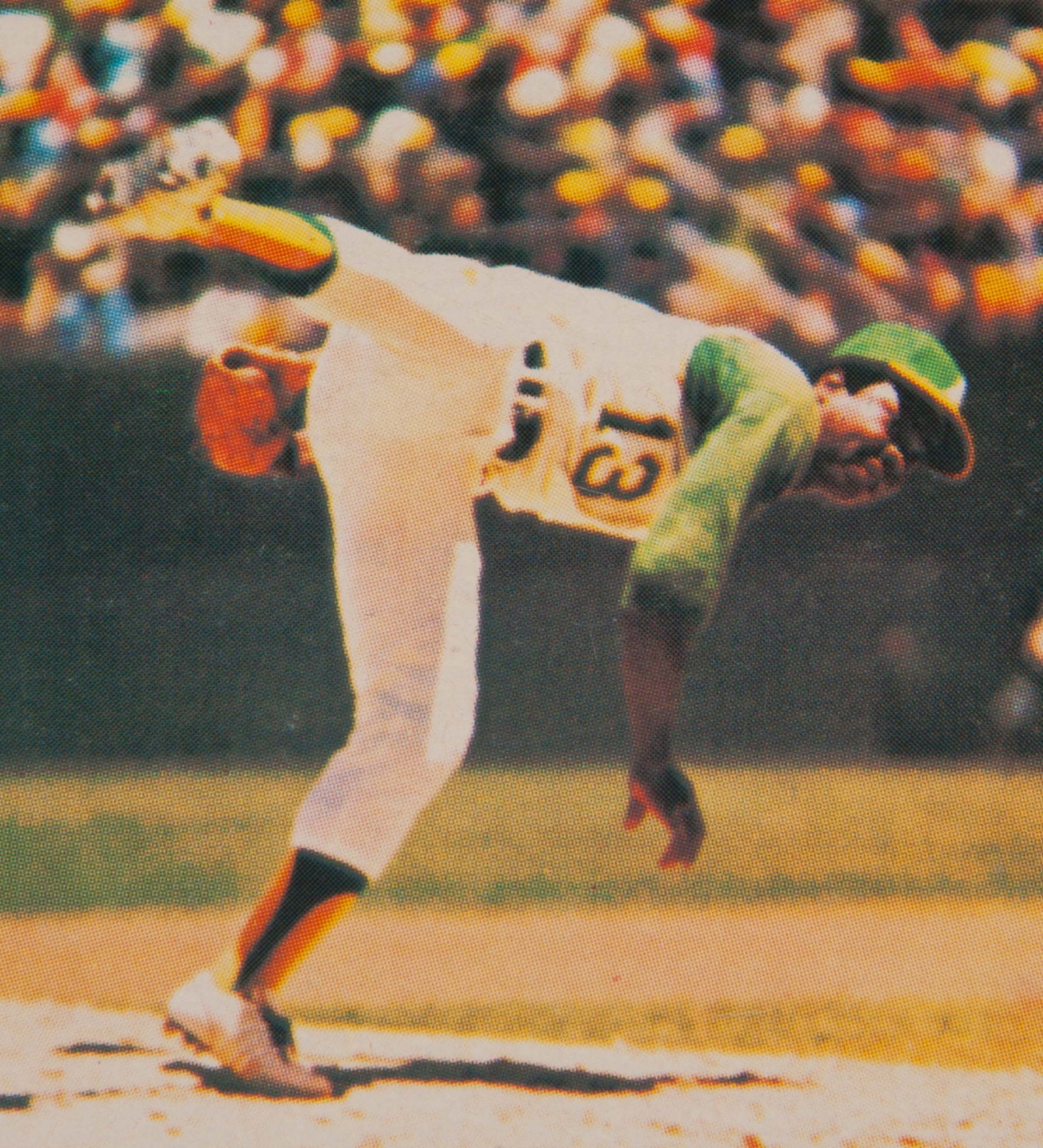

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Blue Moon Odom

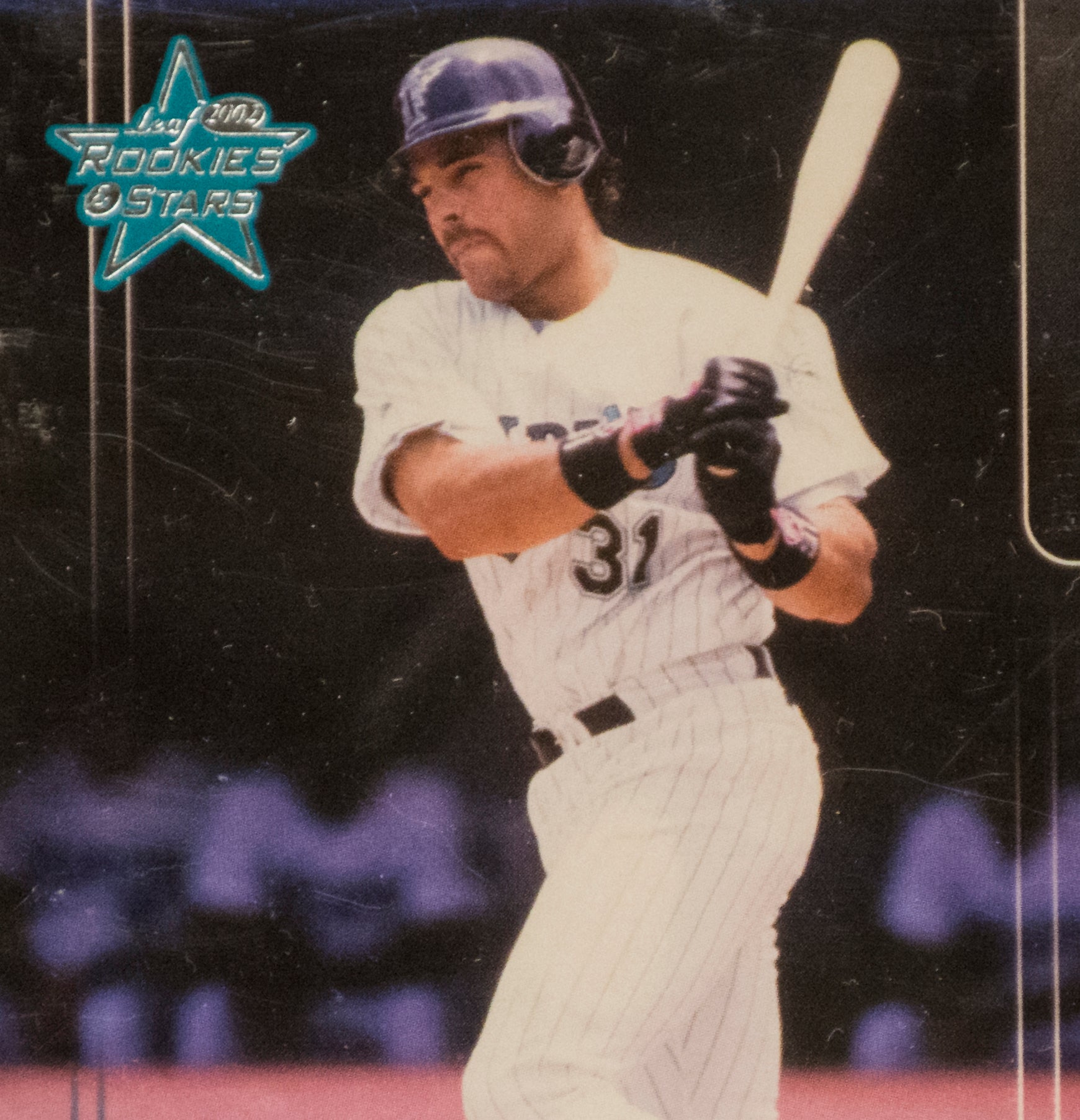

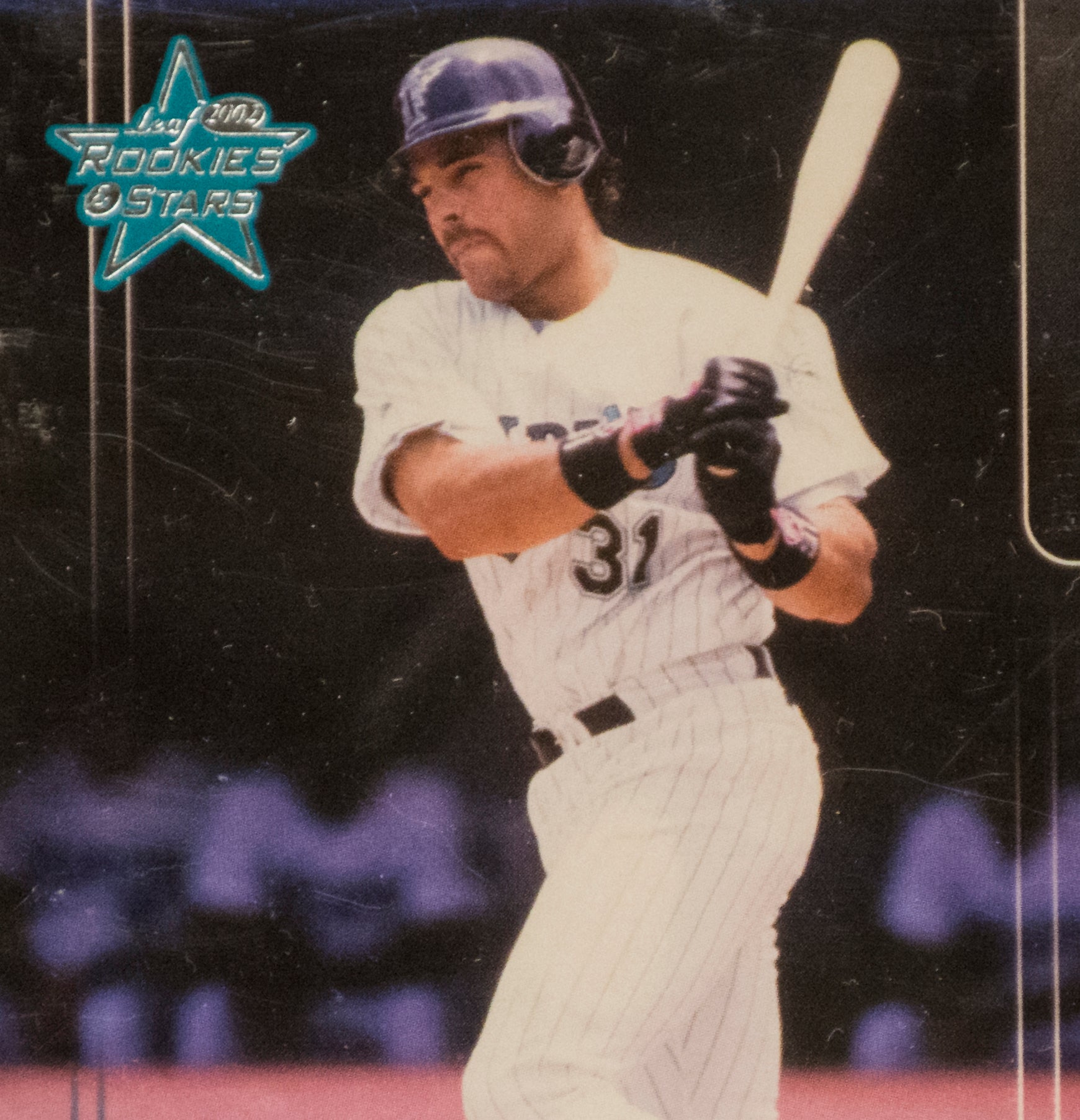

#CardCorner: 2002 Leaf Mike Piazza

#CardCorner: 1977 Topps Mark Fidrych

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Blue Moon Odom