- Home

- Our Stories

- Hack Wilson, Art Shires mixed baseball and boxing more than 80 years ago

Hack Wilson, Art Shires mixed baseball and boxing more than 80 years ago

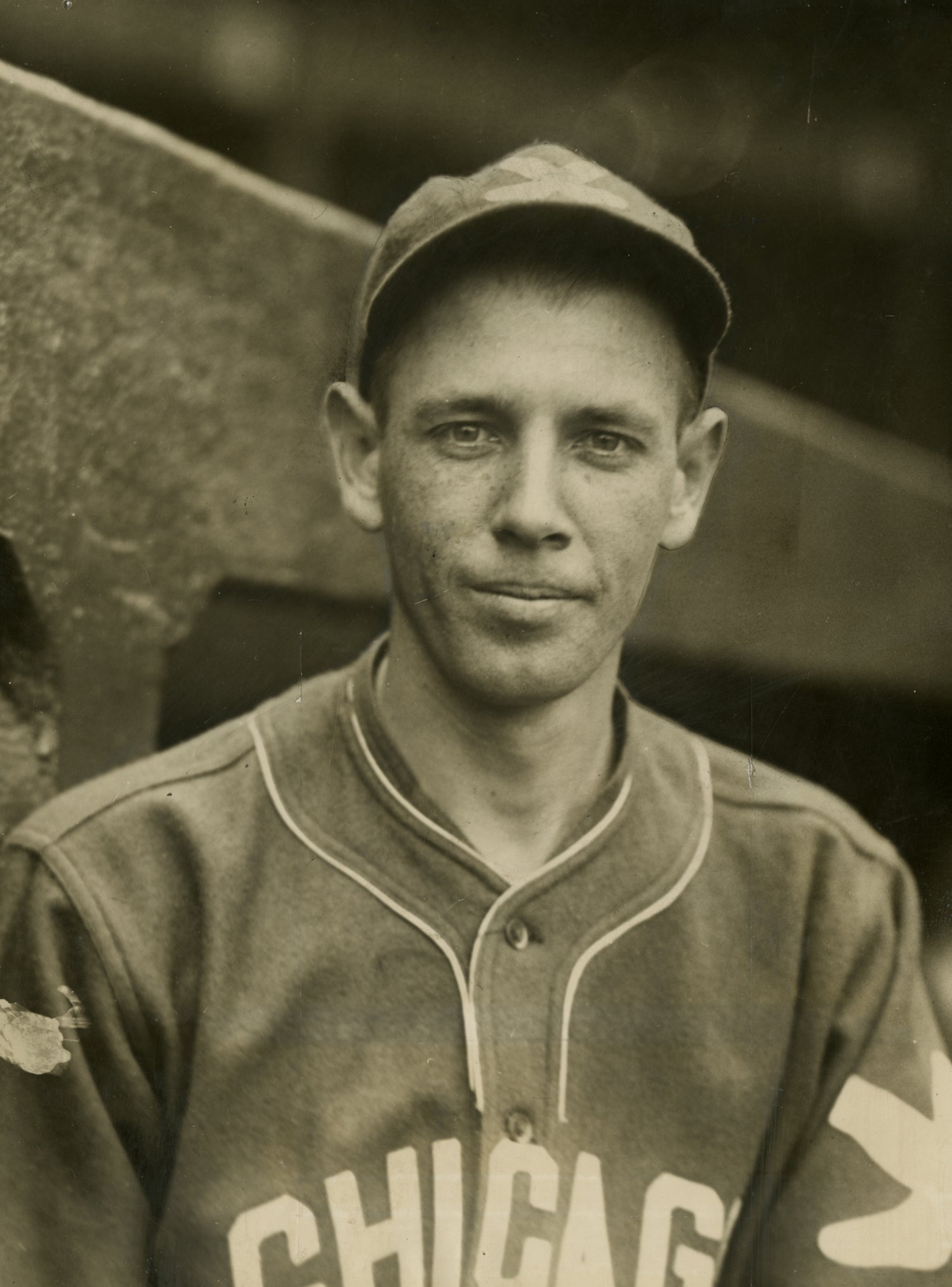

When Art Shires passed away 50 years ago, obituaries for the former big leaguer called him “brash,” “boastful” and “a hard-hitting athlete on and off the baseball field.” He was also fined and suspended by beating up his manager, tried and acquitted of the murder of a longtime friend and gained a national profile for a potential boxing match with a future Hall of Famer.

While the sports world is breathlessly anticipating an Aug. 26 bout between mixed-martial artist Conor McGregor and Floyd Mayweather, newspapers almost nine decades ago – with the Roaring Twenties coming to an end – were also touting a possible fistic curiosity, this one between Shires, a Chicago White Sox first baseman known as “The Bad Boy of Baseball,” and a fellow Windy City slugger, Cubs centerfielder Hack Wilson, who was considered by some “The Dempsey of the Dugouts.”

In the early throes of the Great Depression and in the midst of the Golden Age of Sports, this possible pugilistic World Series, at a time when baseball and boxing reigned supreme on the sporting landscape, was gaining momentum.

Shires, a bragging blond Texan, was just 23 and coming off a season in which he batted .312 in 100 games. He explained that he gave himself the moniker, “Art the Great,” his first day in the majors after getting four hits in five times at bat. “So this is the great American League I’ve heard so much about,” the rookie said. “I’ll hit .400.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

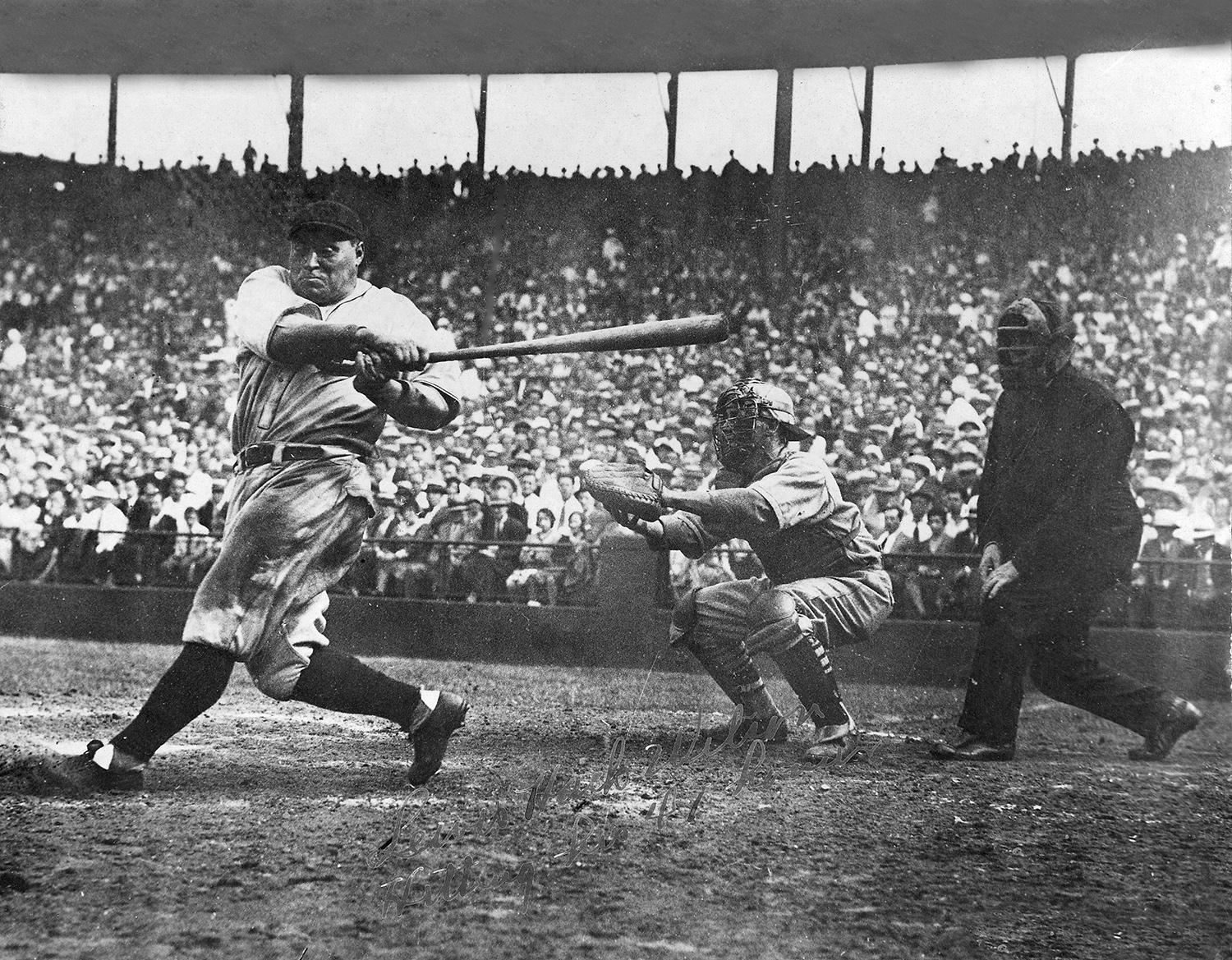

Wilson, his National League counterpart, was, at 29, one of the game’s top players, having led the Senior Circuit in homers for three straight season, from 1926 to ’28, and in 1929 the topped the majors with 159 RBI and led his club to the pennant. Unfortunately for Wilson, though he would hit .471 in the World Series, he gained the derisive nickname “Sunny Boy” for losing a couple fly balls in the sun in his team’s five-game Fall Classic loss to the Philadelphia Athletics.

While the two were successful ballplayers, their physiques were quite different. Both weighed about 190 pounds, but Shires stood at 6-foot-1 and Wilson 5-foot-6. Shires claimed to have persistently turned down requests of nationally famous sculptors to pose for them; Wilson was called “pudgy,” “rotund,” “barrel chested and broad shouldered” but “from the waist down he’s built like a dancer with piano legs.”

Both Shires and Wilson had gained notoriety with their fists during the 1929 campaign so it came as no surprise when speculation arose about a boxing championship of major league dugouts.

In a July 4, 1929 doubleheader at Wrigley Field, Wilson hit three singles and two Reds pitchers. In the fifth inning of the second game, the Cubs outfielder attacked Ray Kolp after the Cincinnati hurler criticized him from the dugout. After the game, as both teams were milling around a train station heading back on the road, Wilson and Pete Donahue went at it after the twirler told the slugger to not pursue another confrontation with Kolp.

“We caution our players against unmanly tactics on the playing field, but in Wilson’s case, it was an exception,” said Cubs President William L. Veeck the next day. “Kolp called him vile names and Hack just couldn’t stand them. He jumped off the field and went into the Cincinnati dugout to stop it. Any man would have done the same thing.

“Wilson, like the rest of the baseball players, takes plenty of insults, but there is a limit to what any human being must or can endure. We are back of him and intend to fight his case to the limit if necessary. He is a gentleman and a conscientious baseball player and has enough red blood in him to resent vile insults such as Kolp hurled at him yesterday.”

Wilson also made fisticuffs news in 1928 when got the better of Edward Young, a milk wagon driver, at Wrigley Field when he jumped into a box and took down the fan who had called him a “fat so and so.”

On July 6, National League President John Heydler announced Wilson was fined $100 and suspended three days for his attack of Kolp. “Whatever your provocation may have been, you were not justified in leaving your base during the game to take the law into your own hands,” Heydler said. “Your actions might easily have started a riot.”

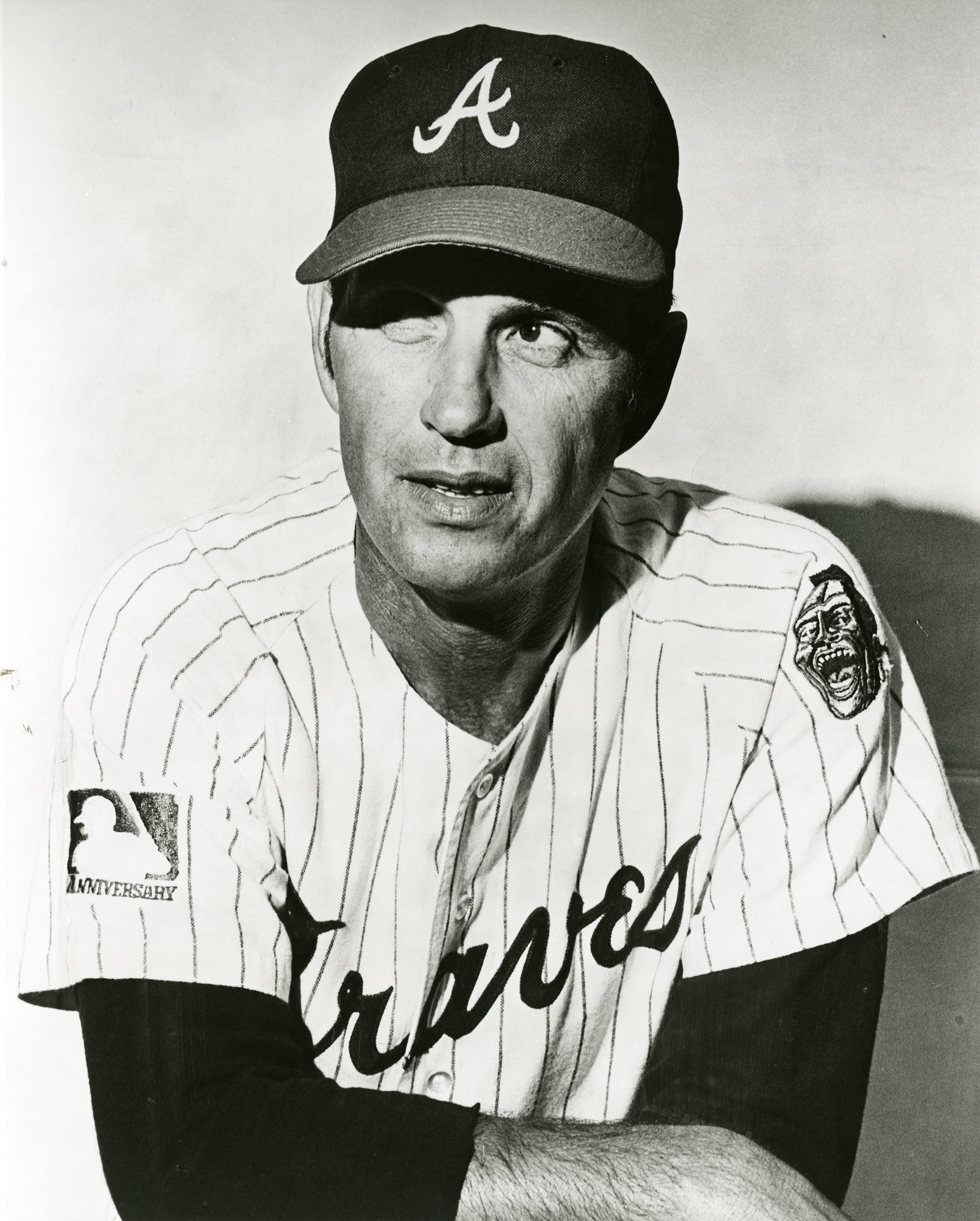

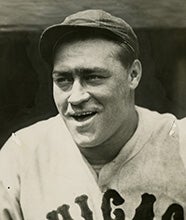

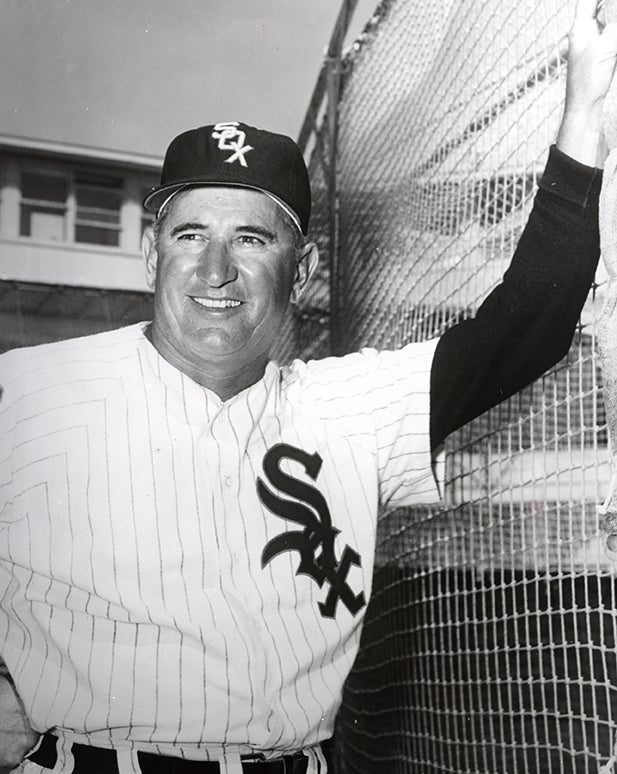

Hack Wilson, pictured above, patrolled center field for the Chicago Cubs for six seasons. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Shires’ 1929 season came to an end when he was indefinitely suspended as the result of a Sept. 13 licking he put on his manager, the White Sox’s Lena Blackburne. In a post-midnight encounter in a Philadelphia hotel, the first baseman blackened his skipper’s eye and attacked traveling secretary Lou Barbour. This episode resulted in Shires’ third suspension on the season and the second time he and Blackburne had fought.

“I regret this whole affair. I am not a fighting ballplayer and I don’t look for trouble. I am considerably embarrassed and worried about the way this will affect my friends and relatives,” Shires said later. “The White Sox club has cost me close to $3,000 this season in fines and suspensions without pay. I am now indefinitely suspended again and I suppose that means for the rest of the season. Well, I’m going into training for professional football now.

“I’m not so sorry about Blackburne’s eye. I don’t believe I ever gave a man such a sweet shiner. It was a masterpiece.”

Instead of a pursing a gridiron career, though, Shires and his fast fists soon find themselves in a professional boxing ring. By late November, news reports stated Shires’ first fight was scheduled for Chicago on Dec. 9 and he admitted unabashedly he had a good chance to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

In his professional boxing debut, and after entering ring sporting a raspberry and deep purple robe that read Art “The Great” Shires, he knocked out Mysterious Dan Daly in 21 seconds before a capacity crowd at the White City Arena. A subsequent investigation found that Mysterious Dan Daly was 18-year-old James Gary from Columbus, Ohio.

“That is how I sock when I’m in good humor,” Shires said. “I’d hate to think what’ll happen if I get mad.”

By mid-December, newspapers across the country had blaring headlines reporting a possible fight between Shires and Wilson in early January, with fight promoter Jim Mullen agreeing to pay Hammering Hack $10,000 with another $1,000 for training expenses. There was even talk that Babe Ruth would referee the fight. Before long, the two potential gladiators were full of confidence in their ability.

“I am no fighter, but if there is $10,000 in it for me, I am ready,” said Wilson from his home in Martinsburg, W.Va. “Sure, I’ll fight. I’m in good shape from hunting and I’m going to start tomorrow strengthening my ring muscles. I’m going to get some of the best fighters in the East to help me brush up on boxing and I’ll give Art a good fight.

“I haven’t thought up any mean things to say about Shires yet, but I guess, with the Cubs-Sox angle, we won’t have to smoke up any grudge stuff.”

Shires wasn’t as kind in his assessment of Wilson.

“Hack will lose sight of my gloves just like he lost sight of the ball in the World Series. But instead of looking at the sun, he’ll be seeing more stars than there are in the heavens,” Shires said. “The fact that Hack belongs to the National League, which really is a minor league, doesn’t prod my major league pride. The worst thing I have against Sunny Boy is that he’s an outfielder and outfielders for the most part are a worthless lot.

“Just another one of those amateur pugs trying to cash in on my reputation. If he lasts one round, which is highly improbable, he won’t have to take off weight this summer. I’ll knock it off,” he added. “Wilson will be alone in that ring after the fight starts. Nobody can help him. He will have to care of himself. If I knock him out I promise to take good care of him by dragging him to his corner instead of leaving him lay alone in the center of the ring.”

According to the Chicago Tribune, “The coming battle of the ages will be basically a fight but beyond that it will bring forth the rivalry of the south side and north side baseball bugs – a veritable city series indoors.

“It will embody all the drawing power of personal appearances in vaudeville – a carnival for the curious.”

Cubs President William Veeck made it clear he opposed a Wilson-Shires battle and said he would refuse permission, but added he could not stop Wilson from going through with the match.

“Wilson is a great ballplayer, but I do not think it is within the province of any ballplayer to become a boxer,” Veeck said. “We cannot prevent a man doing what he pleases in the offseason. His contract, which has yet to be renewed, covers athletic endeavors, and if he fights he will violate that clause. Also, he will be fighting as plain Hack Wilson, and not as the Cubs’ centerfielder.

“This is a free country and Wilson is a free citizen. Wilson if he chooses can go through with the fight on his own volition, but will not have our permission.”

With Cubs officials trying to persuade Wilson not to fight, Mullen boosted his offer from $10,000 to $15,000. Wilson was receiving a reported salary of $17,000 per season with the Cubs at the time.

“Don’t do that,” pleaded Hack to Mullen. “I didn’t sleep a wink last night because I was too busy counting $10,000. Now I won’t be able to sleep again tonight, for there’s $15,000 to count this time.

“I think I can convince Mr. Veeck that I won’t get hurt even if Shires knocks me out, which he won’t do, of course. I know from experience that I haven’t got a glass chin, but I have been knocked out by better men than Shires ever will be and it wasn’t so bad – just seeing canaries and rainbows and pretty stars – rather pleasant in fact.”

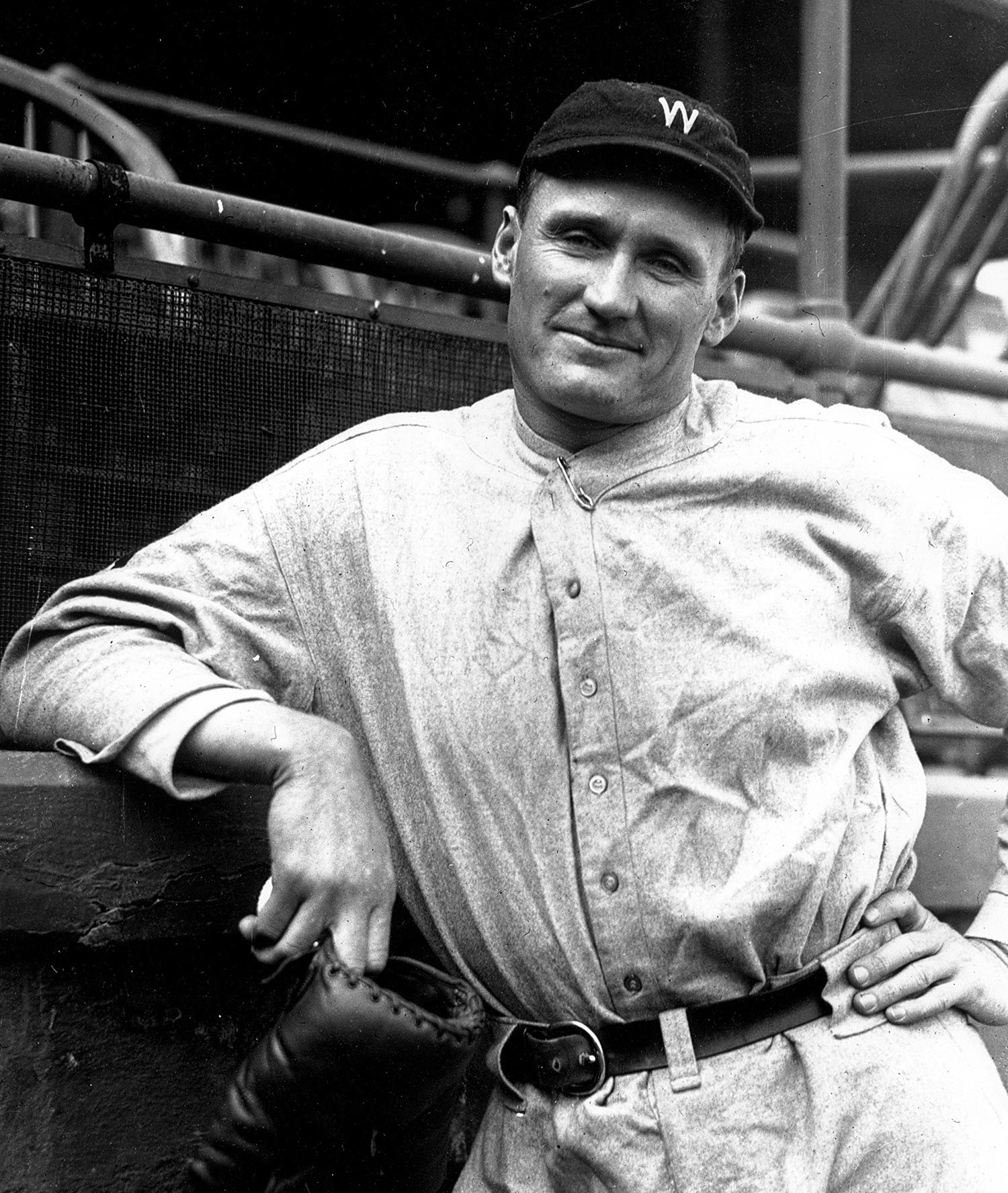

Washington Senators pitcher and future Hall of Famer Walter Johnson made his thoughts clear regarding Shires’ boxing future.

“Shires is just a loud speaker,” Johnson said. “Nobody ever heard of the fellow Shires knocked out recently and the promoters probably will build him up by matching him with a few setups. The first time he meets a real fighter, he’ll probably be knocked back into baseball again. Once he is beaten, interest in him in the ring will burst like a bubble, for boxing fans want to see good boxing the same as baseball fans want to see a team put up a good game.”

Before his fight with Wilson came to fruition, though, Shires had an ill-advised boxing match with Chicago Bears center George Trafton. Trafton, then in the midst of a 12-season career with the Monsters of the Midway, would eventually be elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1964.

“Shires thinks he is a great fighter because he knocked over that pushover a week ago, but the folks can quit worrying about a Shires-Wilson go after I get through with him tomorrow night,” Trafton said on Dec. 15. “I’ll take care of that sucker like he took care of Dan Daly.”

Trafton would prove prophetic, knocking a much lighter Shires to the canvass three times in five rounds in a decisive decision before 5,000 boisterous patrons at a sold-out Chicago’s White City Arena on Dec. 16. Shires, in his second appearance as a professional fist fighter, weighed 179 ¼ pounds and Trafton 218 ¾ pounds. And for all intents and purposes, the White Sox first sacker’s defeat ruined any chance of a big-money bout with Wilson.

“I didn’t want to fight Trafton anyhow,” Shires said. “Think how much the guy weighs – 40 pounds more than I do. If I knocked him out, what credit would I get? He was too big for me, he weighed too much. It was a sucker match. I’m going to tell my manager that when I see him, and if he gets fresh, I’ll punch him in the eye. I still can fight. Get Wilson for me.”

Trafton was overjoyed after his triumph.

“Licking Shires was easier than getting kicked around a football field,” said Trafton. “If I had been in better shape the Great Man would have been stretched on the canvas, dead to the world, before the second round was over.”

Reached at his West Virginia home with the news of Shires’ beating, Wilson sounded relieved.

“Well, you can tell the world,” Wilson said, “that there needn’t be any more talk about me going to Chicago to fight Shires. I’ve been undecided all along, what with wanting to grab that $15,000 and yet not wanting to offend Mr. Veeck or cross my wife. Now I know what I’m going to do. I’m going to stay right here in Martinsburg and get ready to play some great baseball next summer.

“If Shires had licked Trafton I guess I might have had to go to Chicago to talk Mr. Veeck into seeing my point. But there’s no use in me bucking the Cubs and making my wife mad just to floor a guy who has already been licked.”

While Wilson seemed content to forget about stepping in the ring, Shires continued in pursuit of boxing glory. After knocking out Bad Bill Bailey in 82 seconds in Buffalo on Dec. 26, Shires took on Al Spohrer of the Boston Braves and came away with a fourth-round technical knockout of the backstop before a capacity crowd of 18,000 at the Boston Garden on Jan. 10, 1930.

“Folks, I didn’t want to hurt Al Spohrer,” said to the crowd after the fight. “I want to hurt Hack Wilson.”

Shires made his career intentions clear before the Spohrer fight. “My interest is in baseball. I came into this boxing racket to make some money. I have got seven brothers and three sisters back home and my ambition is to go back home sometime with a quarter of a million dollars.”

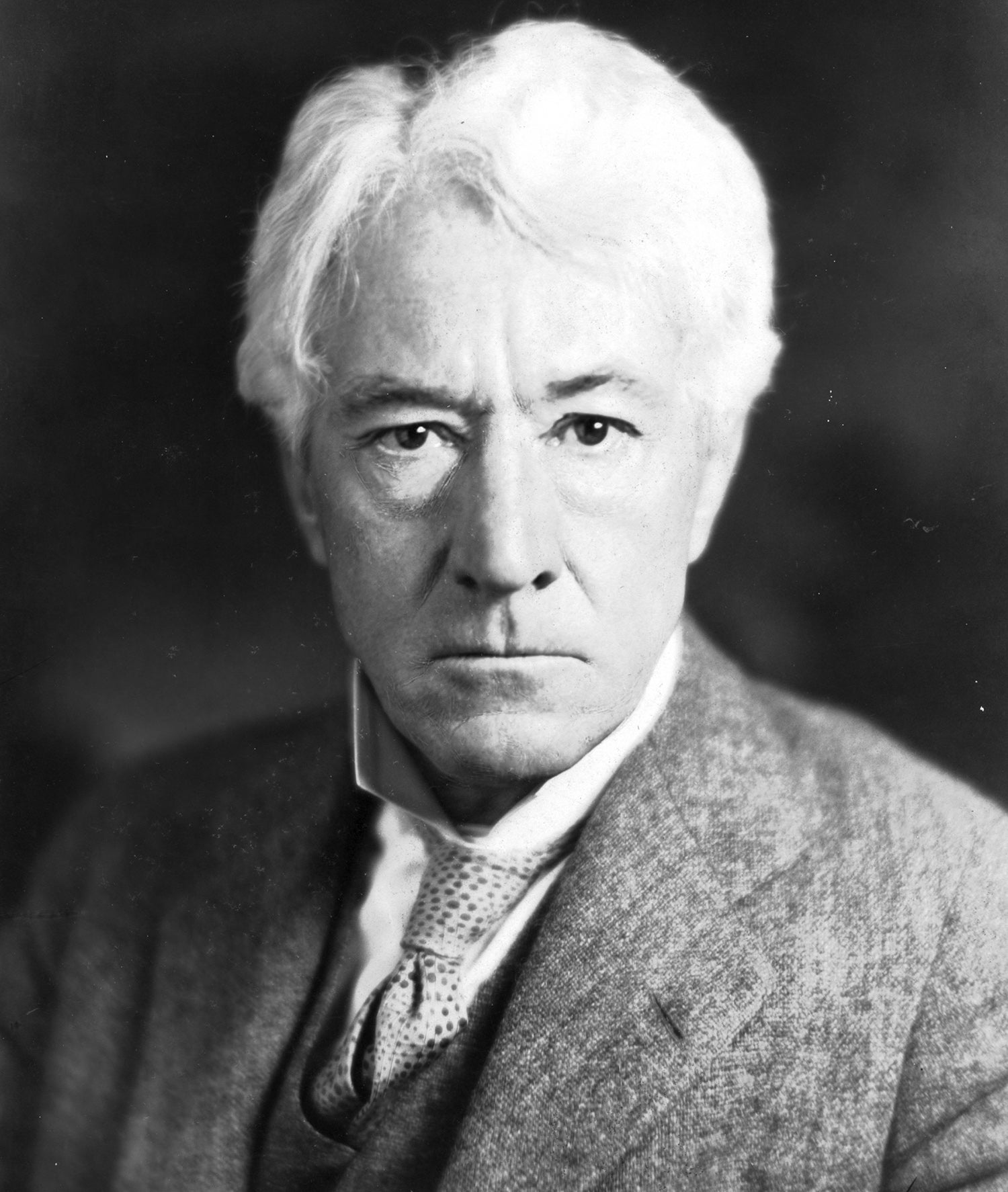

But Shires’ hopes of a major payday with a Wilson fight were soon dashed by a ruling from a higher authority. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, after a Jan. 18, 1930, meeting with Shires, declared ballplayers who engage in professional boxing will be considered retired from baseball.

Landis’ 33-word statement was clear and to the point: “Hereafter any person connected with any club in this organization who engages in professional boxing will be regarded by this office as having permanently retired from baseball. The two activities do not mix.”

Thus Shires was forced to retire from the fight game with a 4-1 record.

“We had a nice talk,” Shires said. “Landis let me tell my story and my story was that I took to boxing because I was broke. I also told him that I was convinced I would never be much more than a chump in the ring, but that I would like to continue for a time at least because of the money in sight.

“Landis was not especially worked up over my case. Every ballplayer in the country was breaking into print with a demand that I give them a date. It was becoming a regular epidemic, so I guess Landis figured he’d better stop the thing before it got beyond control.”

After his flirtation with boxing during the offseason, Wilson returned to baseball and had arguably his greatest season in 1930: 191 RBI (still the all-time major league record), 56 home runs (a National League record for 68 years) and a .356 batting average. Lewis Robert Wilson, who would pass away at the age of 48 in November 1948, would be elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979.

The year Wilson died, Shires announced his candidacy for the Texas legislature. A knee injury had ended Shires’ big league career in 1932 after four seasons. He finished with a lifetime batting average of .291.

“Labor’s going to be for me and so will all the people in sports,” said the 41-year-old Shires, who was then operating a restaurant in Dallas. “And the sportswriters all ought to back me; I’ve furnished them enough copy.”

Though Shires would be defeated in his political race, the former slick-fielding first baseman would soon find himself in life-or-death fight. In December 1948, he was charged with the murder of Hi Erwin, a friend for 25 years. The charge said Shires willfully and with malice aforethought killed Erwin by beating him with his fists and stomping him with his feet during a fight on Oct. 3. According to detectives, Shires said he went to Erwin’s place of business to give him a steak.

“He hit me across the face with a telephone receiver and I knocked him down without thinking,” the detectives quoted Shires as saying. “I had to rough him up a good deal because he grabbed a knife and started whittling on my legs.”

After a February 1950 trial, a jury found Shires guilty of simple assault and fined him $25. The court found that Erwin’s death was caused by pneumonia and cirrhosis of the liver and not by the fight injuries.

Shires himself would pass away on July 13, 1967, one month before his 61st birthday. His obit in the Washington Post, appropriately enough, wrote of the “death to the so-called Bad Boy of Baseball,” one who had a brief but colorful career in and out of big league baseball.

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

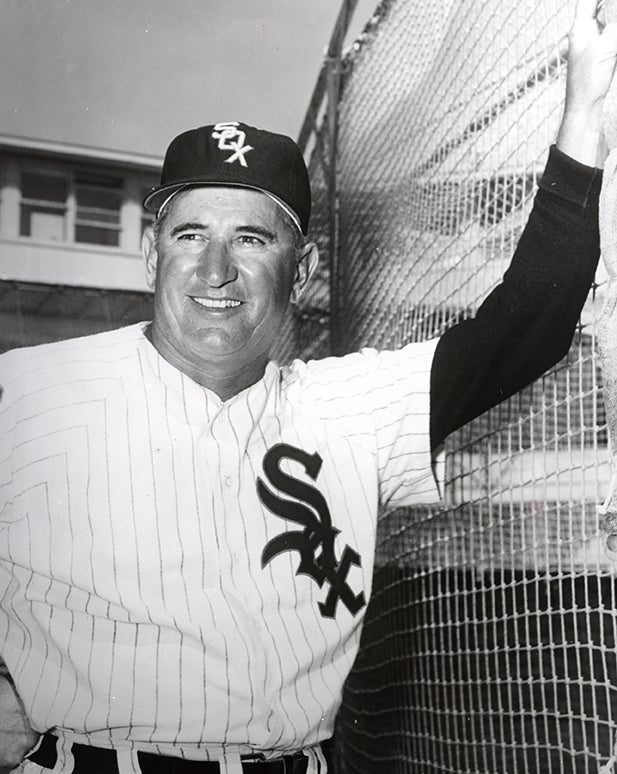

Future HOFer Al López named manager of Chicago White Sox

Bill Veeck Returns as White Sox Owner

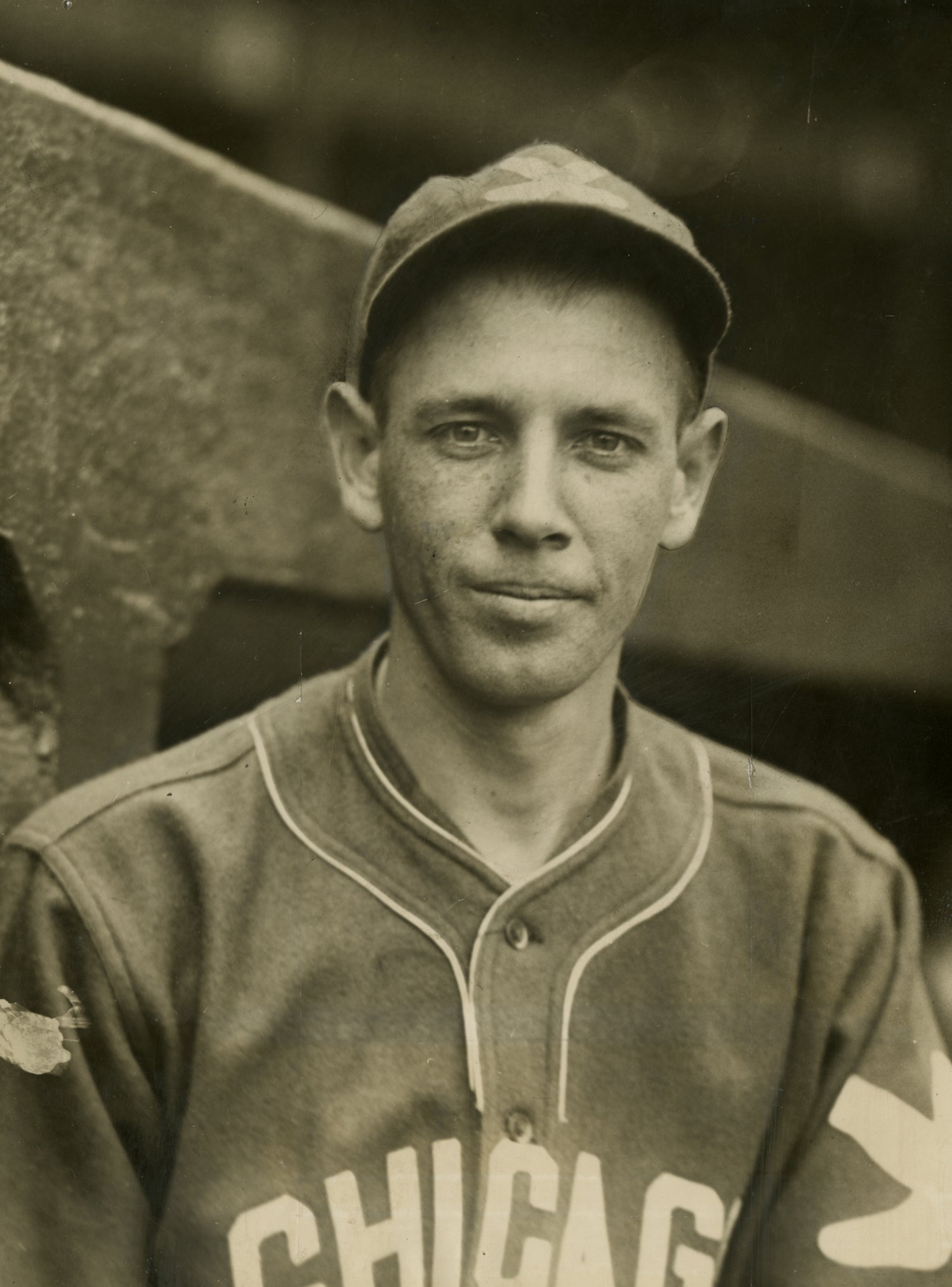

Steady Ted Lyons thrived as White Sox ace

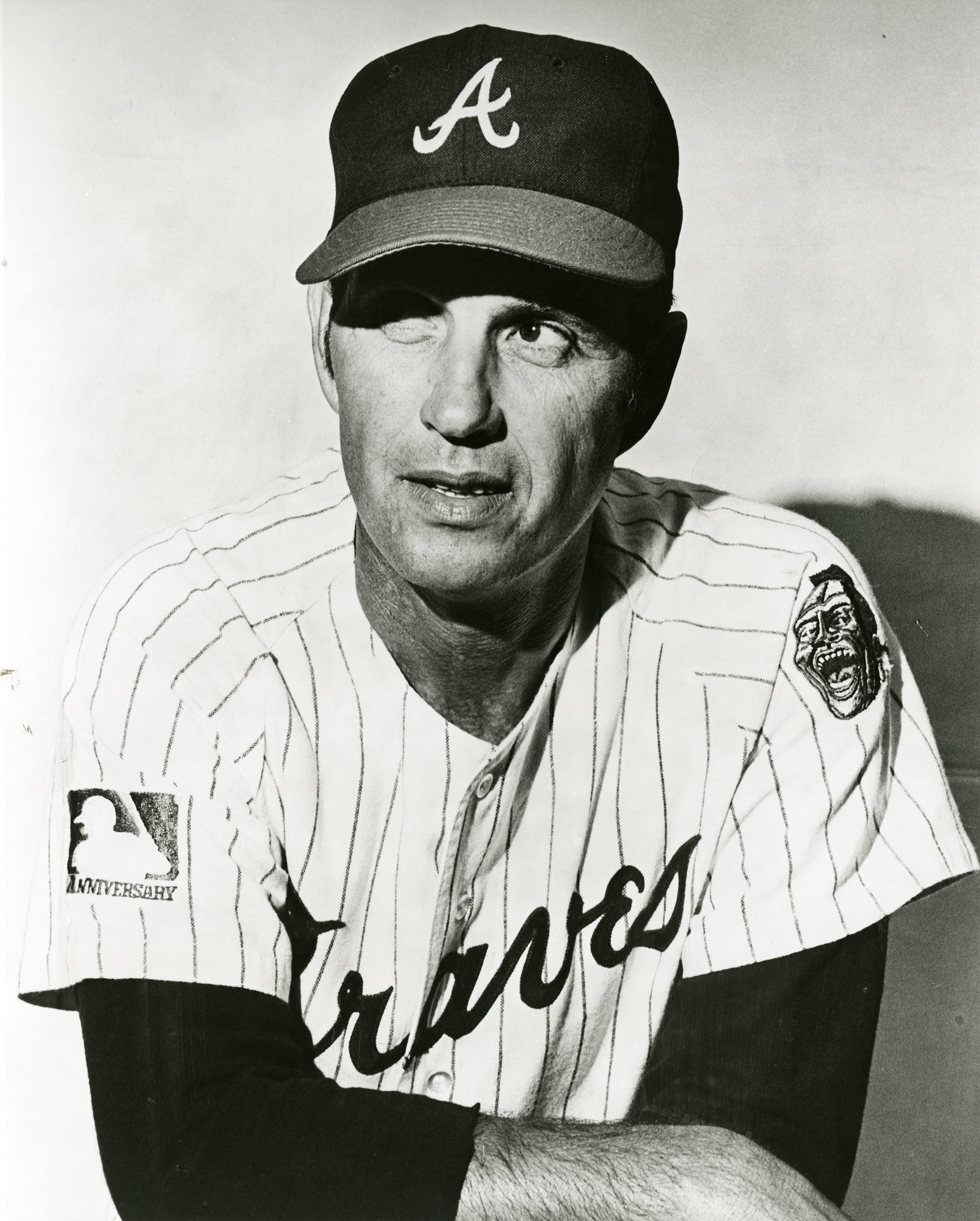

Cubs trade Hoyt Wilhelm to Braves for Hal Breeden

Future HOFer Al López named manager of Chicago White Sox

Bill Veeck Returns as White Sox Owner

Steady Ted Lyons thrived as White Sox ace