- Home

- Our Stories

- Dock Ellis’ journey helped him shine a light for others

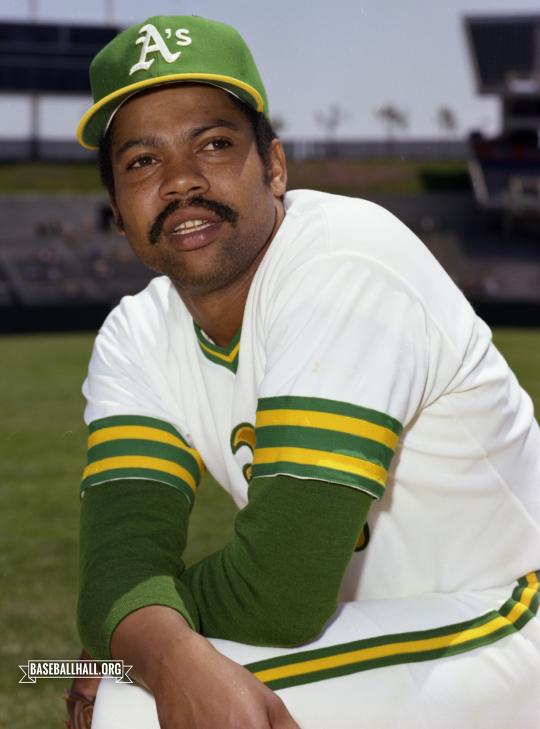

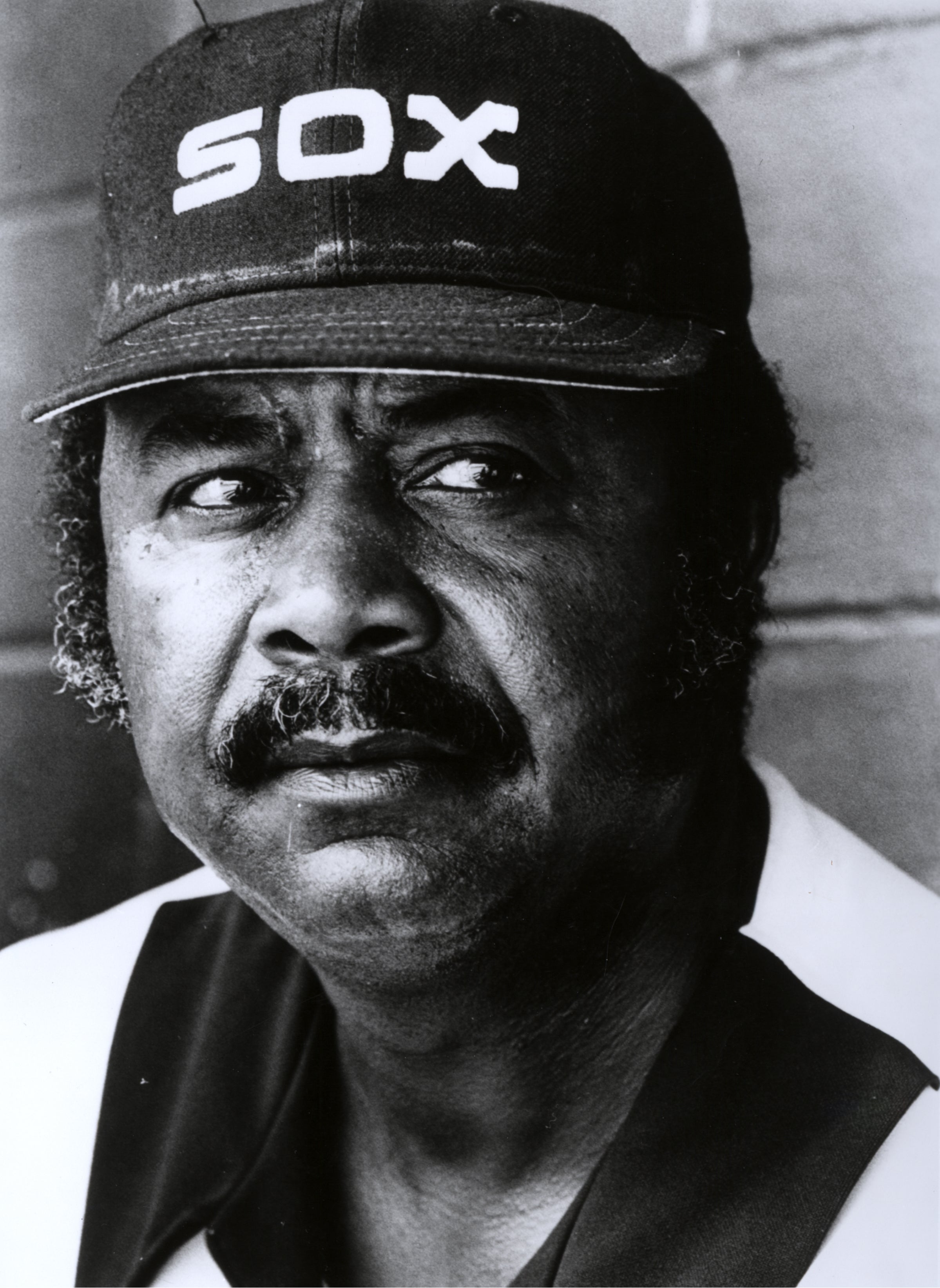

Dock Ellis’ journey helped him shine a light for others

Sometime in 1984, Dock Ellis told a reporter for the Pittsburgh Press that he had pitched a no-hitter 14 years earlier while under the influence of LSD.

In the years since that revelation, some skeptics have cast doubt on the validity of the story. Yet, the former Pittsburgh Pirates’ ace, one of the most vocal Black players of his era, never backtracked from any of his initial claims.

“I can only remember bits and pieces of the game,” Ellis told the Pittsburgh Press in ‘84 “I had a feeling of euphoria. I was zeroed in on the glove [of catcher Jerry May], but I didn’t hit the glove too much. I remember hitting a couple of batters and [that] the bases were loaded two or three times.”

In actuality, Ellis hit only one batter that night at San Diego Stadium, but he was certainly wild against the Padres – incredibly wild. Ellis walked eight Padres during his June 12, 1970, no-hitter, an unusual occurrence for a pitcher who usually featured more than decent control. Although it’s impossible to say with any certainty, Ellis’ lack of control that night may have stemmed from the effects of LSD.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

While there remains uncertainty over Ellis’ use of LSD immediately prior to that historic game, he did not romanticize his drug abuse and its alleged connection to the no-hitter. He was not proud of it. But there’s little doubt that his abuse of drugs and alcohol persisted throughout his major league career.

Ellis’ problems with addiction may serve as an explanation for at least some of his behavior, which was often controversial, or in some cases, simply bizarre. In one of his most memorable incidents, which took place at Wrigley Field in August of 1973, Ellis made his way out onto the field during pregame warmups in an unconventional manner. Emerging from the clubhouse, Ellis walked out onto the field en route to the bullpen, all the while sporting a head full of hair curlers. While such a look might not prompt much news coverage in today’s game, baseball remained a remarkably traditional sport in the early 1970s. Ellis’ appearance shocked several of his Pirates teammates and his manager, Bill Virdon. The Pirates skipper instructed one of his players, first baseman Bob Robertson, to walk out to the bullpen and tell Ellis to remove the hair curlers from his head. Ellis refused the request.

The Commissioner of Baseball, Bowie Kuhn, did not appreciate Ellis’ stunt any more than Virdon did. Kuhn threatened to fine and suspend Ellis if he repeated the on-field hair curler incident again. The Pirates’ organization, including Virdon and team scouting director Harding “Pete” Peterson, echoed that sentiment. In response to the directive, Ellis felt that a double standard was being applied to him and hinted that it involved the issue of race.

“They didn’t put any orders about Joe Pepitone when he wore a hairpiece down to his shoulders,” Ellis said, referencing the former New York Yankees outfielder and first baseman. After initially threatening to make the curlers a more regular occurrence, Ellis eventually backed off, restricting their use to his home.

In retrospect, the hair curler episode seems more amusing than it does controversial. But an incident during the following season carried more dangerous and potentially damaging overtones. It occurred during a series with the Cincinnati Reds in May of 1974. At the time, the Reds and Pirates were embroiled in an intense rivalry. Prior to the series, several Reds, noting the team’s recent success against Pittsburgh, made condescending remarks about the Pirates.

Most of the Pirates players sloughed off the comments, at least publicly. But not Ellis. The words of the Reds’ players burned inside of him. He felt that the Reds needed to be punished for what they said. And he decided to inflict that punishment on May 1, the night that he started against the Reds.

In the first inning, Ellis prepared to face the top of the Cincinnati order: Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Dan Driessen. Of Ellis’ first five pitches of the game, three of them resulted in hit batsmen. Ellis hit each batter with a fastball. Even with the bases now loaded, Ellis was not satisfied. He continued the onslaught, aiming a pair of pitches behind the head of cleanup batter Tony Pérez. Unable to connect with Pérez, Ellis walked the Reds’ first baseman, forcing in a run.

Still, Ellis refused to let up on his game plan. He threw two pitches in the direction of Johnny Bench, each pitch barely missing his intended target. Remarkably, home plate umpire Jerry Dale allowed Ellis to continue his performance and chose not to eject the pitcher from the game. In contrast to the umpire, Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh had seen enough. He walked to the mound and removed Ellis from the game before he could do any more damage, either to the Reds batters or to himself.

The incident against the Reds carried no connotations of amusement or silliness. Though none of the Reds’ players suffered any kind of injury, Ellis’ recklessness could easily have resulted in serious physical damage. For a player who often seemed to seek out conflict, his rampage against the Reds represented a low point in his career.

Another ugly incident took place in 1975, shortly after Murtaugh moved Ellis to the bullpen. On at least three occasions, Murtaugh summoned the veteran right-hander to pitch in relief, but Ellis refused each time. After the third refusal, Murtaugh suspended Ellis for one game. The next day, Ellis called a team meeting, at which time he was expected to apologize to Murtaugh and the team. Instead, he began to berate Murtaugh, who was generally beloved by the Pirates’ players. The manager, normally a mild-mannered sort, responded by cursing at Ellis. A fight between the two men nearly ensued, but several players interceded before punches could be thrown.

Ellis’ verbal tirade resulted in a 30-day suspension. Ellis finally apologized to Murtaugh, ending the ban.

Ellis was naturally rebellious and outspoken, and at times he did channel those qualities into laudable efforts. He often spoke out about racial injustice, both in and out of the game. And in the early 1970s, he regularly visited Pittsburgh’s Western Penitentiary, which featured an inmate population that was 70 percent Black. Ellis offered advice to inmates while also advocating for prison reform, where he felt some prisoners were being treated like they were in “a concentration camp.”

At other times, Ellis’ behavior turned erratic and unpredictable, seemingly exacerbated by his involvement with drugs and alcohol. Those chemical habits did not begin during his playing career. Instead, they found roots as far back as his days at Gardena High School in Los Angeles, when Ellis was caught smoking marijuana and drinking alcohol in one of the school bathrooms. The school contemplated expulsion, but ultimately allowed Ellis to remain a student – and pitch for the Gardena varsity baseball team.

Ellis’ drug addiction continued after the Pirates signed him in 1964 and assigned him to their minor league system. As with many Black players of the era, Ellis endured heckling from fans, often racist in nature. In one particularly nasty incident, Ellis was taunted so severely that he picked up a baseball bat, made his way into the stands, and attempted to track down the heckler.

Ellis also faced pressure to succeed, largely because he was regarded as one of the Pirates’ “can’t-miss” prospects. In addition to his recreational drug use, he began taking amphetamines. Prior to his starts, Ellis typically used amphetamines like Benzedrine and Dexamyl (known as greenies). “I was into the ‘speed’… to hurry up and get to the big leagues,” Ellis told the Los Angeles Times in 1985. “I had a no-miss tag on me… That’s a lot of stress.” Ellis became so addicted to amphetamines that he claimed he could not take the mound without them. For the rest of his career, Ellis consumed pep pills on the day that he was scheduled to start.

By the late 1960s, Ellis had added cocaine to his list of preferred drugs. And if we are to believe the story of his no-hitter, he would add the use of LSD to the list by the time that the 1970 season began. In a 1985 interview with USA Today, Ellis recounted his path of addiction. “I went from liquor to marijuana, from marijuana to cocaine, to amphetamines and everything else,” Ellis told writer Mark Celender. “Then something started going on inside of me. I cut back on drugs and started drinking. But then I found myself drinking stuff I didn’t like. It took me months before I realized how much I was drinking.”

As Ellis made more money in the major leagues, his abuse of drugs grew, gradually and steadily. “I was on drugs every time I took to the field,” Ellis revealed to Celender. “Quite frankly, I had a chance to injure a lot of lives… Thank God, I didn’t hurt anyone [on the field].”

But Ellis did hurt himself. The heavy consumption of drugs and alcohol affected Ellis’ health, both physically and mentally. It also took a damaging toll on his personal life, especially his various marriages. Ellis was married four times, with three of them ending in divorce. Two of those divorces occurred with Ellis in the throes of drug abuse.

In November of 1979, the Pirates released him, a move that essentially signaled the end of his career. Ellis took out his frustrations at home. He flew into a rage and reportedly brandished a gun. His loud and violent outburst so traumatized his wife, Austine, that she left the house and went to a local hospital. She would never return to Ellis.

With both his marriage and his playing career over, Ellis had reached rock bottom. He realized that he needed to make a substantial change to his life. In 1980, he sought help from former major league pitcher Don Newcombe, who had overcome his own problems with alcoholism. Newcombe arranged for Ellis to enter The Meadows, a famed rehabilitation center in Arizona. Ellis stayed at The Meadows for 40 days, beginning his commitment to end his use of drugs and alcohol.

Not long after his successful rehabilitation stint, Ellis decided to turn his experiences with drugs into a positive effort aimed at assisting others. He started working as a counselor through psychotherapy sessions and eventually became the director of the substance abuse program at the California Institute for Behavioral Medicine in Los Angeles. At times, he counseled major league ballplayers struggling with addiction.

As part of his work, Ellis became a motivational speaker who pushed forth his message to younger generations. Often becoming emotional during his talks at schools and with prison inmates, Ellis implored his audiences to stay away from drugs. He urged them not to repeat the mistakes that he had committed during his years in baseball. He pointed out how his constant abuse of drugs and alcohol had affected his behavior, created conflict with his managers and teammates, and ultimately cost him his marriage.

“What we need to educate our young about is the abuses of drugs and alcohol,” Ellis told USA Today in 1985. “When I say young, I mean starting with kindergarten. That’s the time when little bitty kids with little bitty eyes start watching and following adults.”

Ellis’ efforts undoubtedly helped many younger people that he met over the years. Unfortunately, his crusade against drugs never received the kind of publicity that had been generated by his many controversies in the 1970s. Little was reported about Ellis by the national media until 2007, when a national newspaper article brought news about the retired right-hander. The article detailed shocking revelations about Ellis’ health, which had deteriorated badly over the last six months. According to the article, Ellis was suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, resulting in a loss of over 60 pounds. Doctors informed Ellis that if he were to survive long-term, he would need a liver transplant.

Sadly, the transplant never came. Later diagnosed with heart disease, Ellis was no longer regarded as a viable candidate for a liver transplant. In 2008, Ellis’ body gave out. He died on Dec. 19, at only 63 years of age.

Not only did liver disease take Ellis at a young age, but it served as a reminder of the damage that his use of alcohol had almost certainly caused to his body. As Ellis himself admitted many times, he had made more than his fair share of mistakes over the years, including his alleged use of LSD prior to a game, his attempts to injure several players on the Cincinnati Reds, and his repeated efforts at undermining his managers. Much of that behavior came about, either directly or indirectly, because of the haze created by alcohol and drug abuse.

But to Ellis’ credit, he did not allow that to become his legacy. Instead, he committed himself to making a change and did his best to make amends – by helping younger generations learn from his failures. He did that for roughly 25 years, or about 40 percent of his life.

Over those last 25 years, Dock Ellis found his way.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

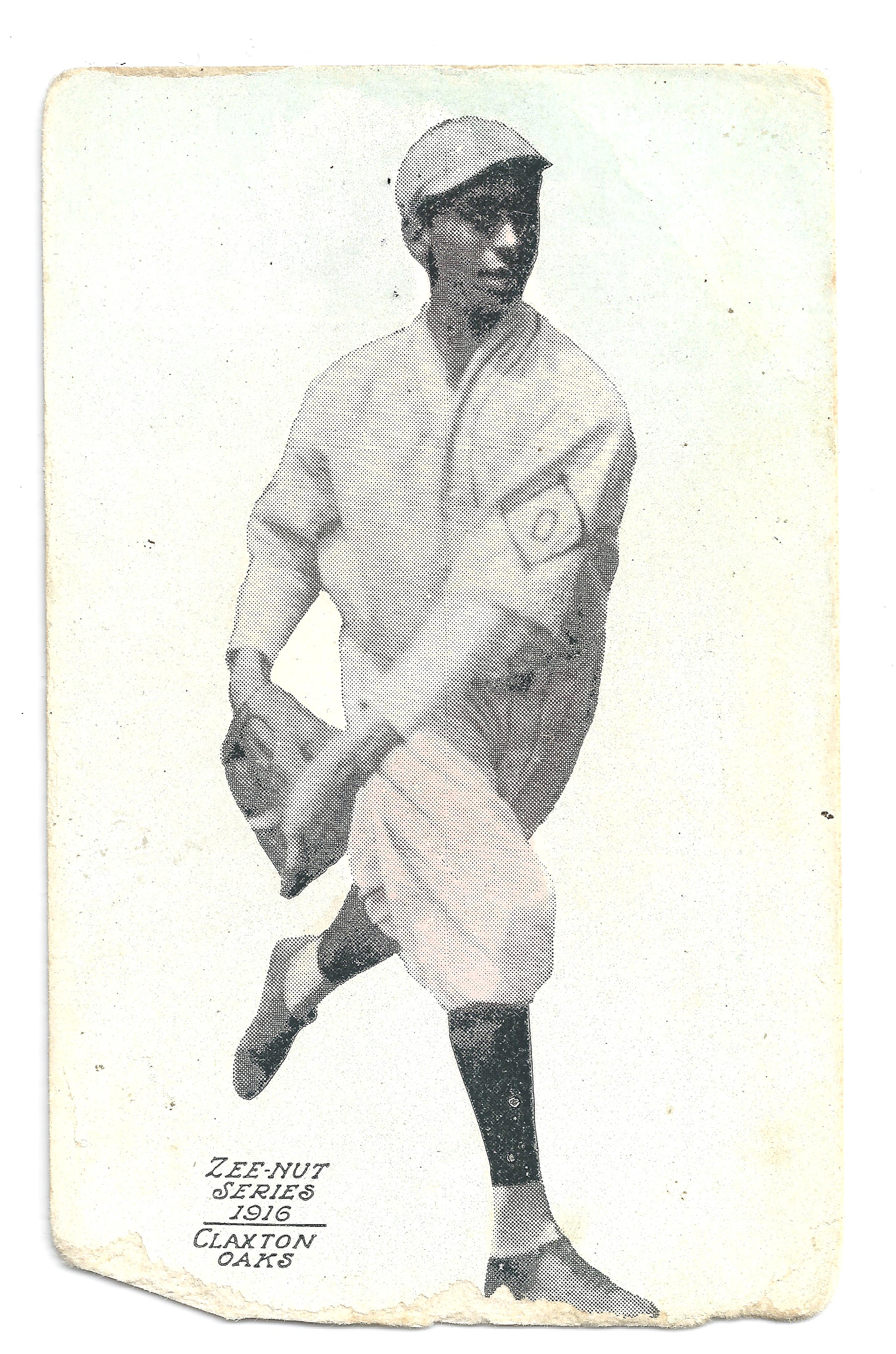

Jimmy Claxton blazed trails via baseball cards

Rickwood Field features baseball’s past and present

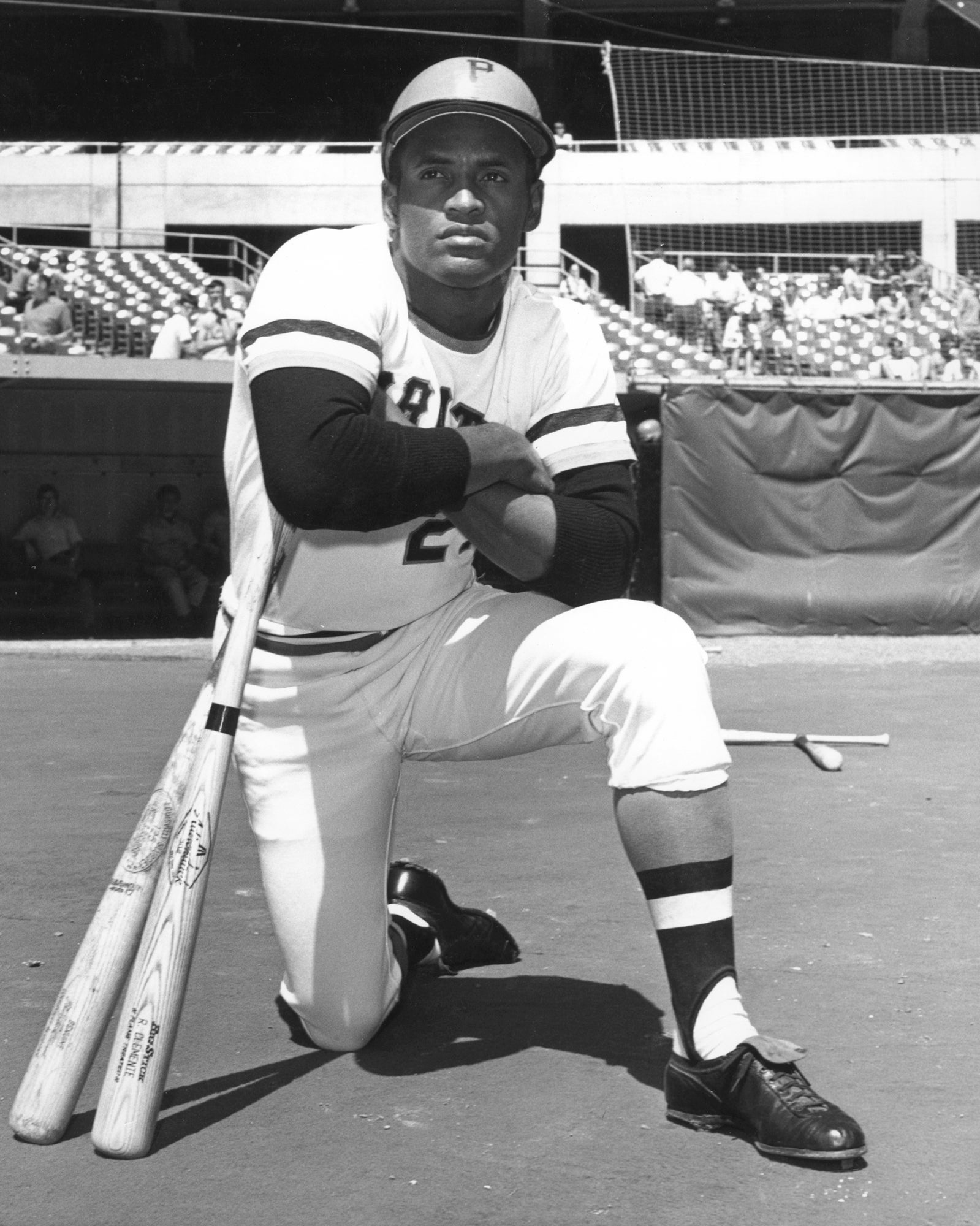

Clemente’s home run powers Pirates to World Series win

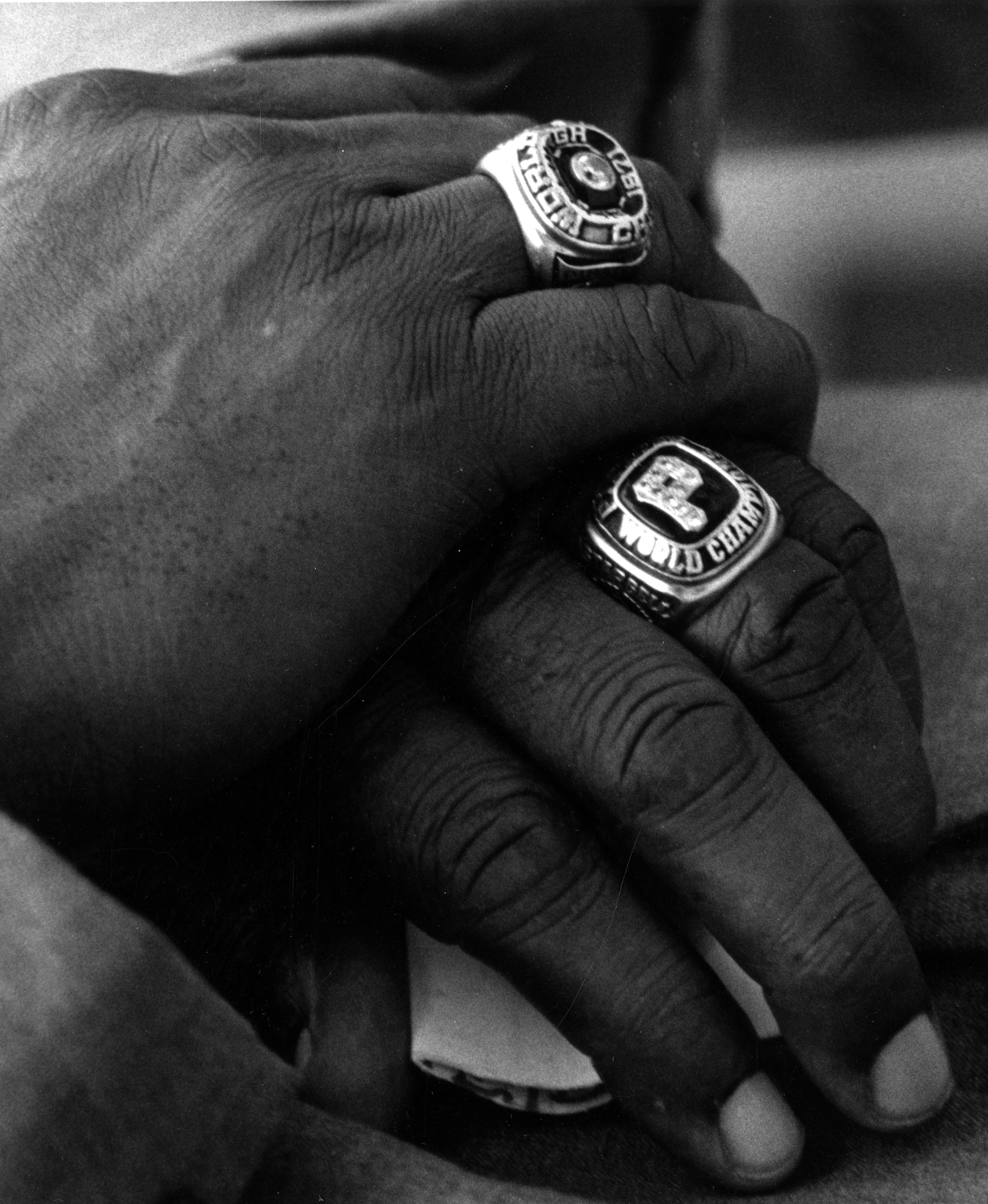

Stargell’s home run powers Pirates to Game 7 win in 1979 World Series

Doby blazed trails on, off field

Related Stories

Dock Ellis’ journey helped him shine a light for others