- Home

- Our Stories

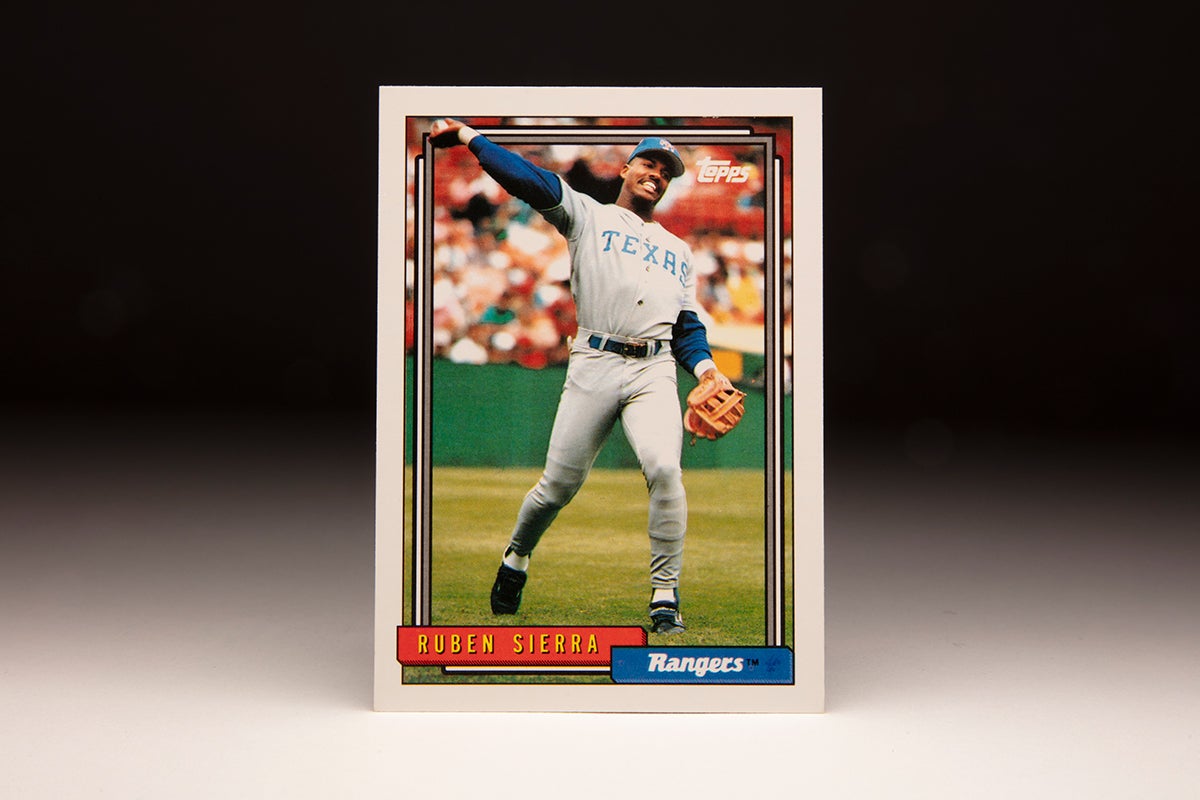

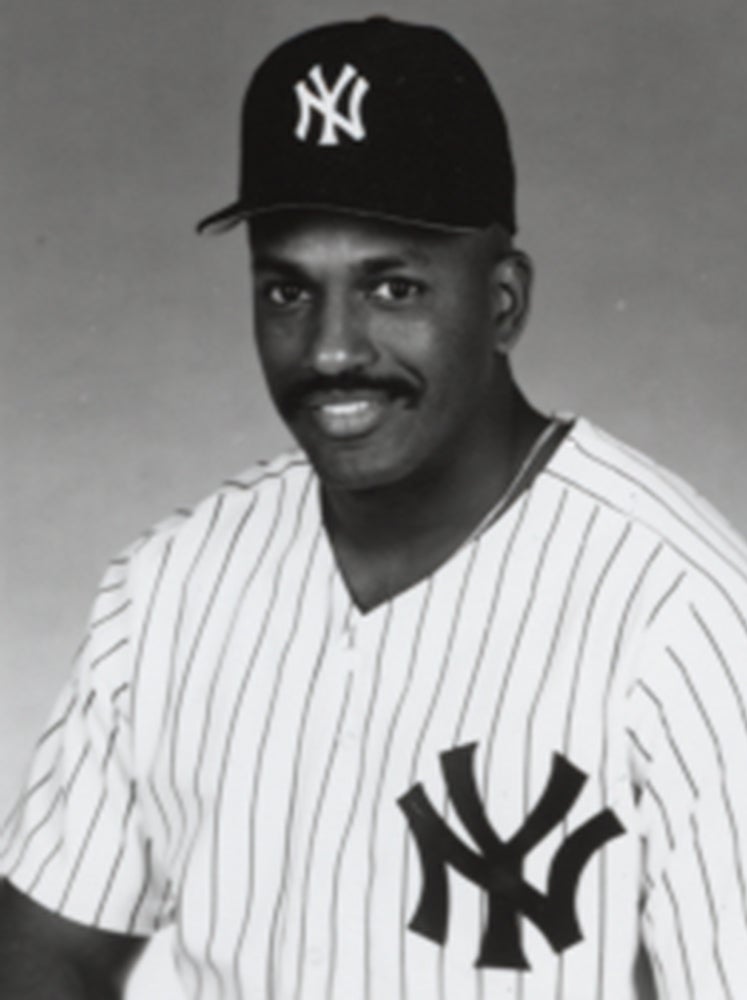

- #CardCorner: 1992 Topps Rubén Sierra

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Rubén Sierra

He was one of the game’s brightest young stars of the 1980s, and by the time Rubén Sierra ended his 20-year big league career his numbers ranked among those of the greatest players ever born in Puerto Rico.

And while his journey is sometimes regarded as unfulfilled promise, Sierra’s final record leaves him in the same category as some of the game’s most accomplished switch-hitters.

Born Oct. 6, 1965, in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico – located just south of San Juan – Rubén Angel Sierra grew up in a home that did not have heat or air conditioning. His father died when Rubén was four years old as the result of injuries sustained in a car accident, leaving his mother – who worked as a custodian – to raise four children.

Sierra’s older brother, Rey, helped him turn his attention to baseball.

“Anytime I had to play a game, anywhere, he would take me in his car, a little Volkswagen,” Sierra told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “And then he would stay and watch. If I was wrong, he’d tell me. He was like a father to me.”

When Sierra was 14, he began attracting a following from big league scouts. In 1982, Jorge Posada – an area scout with the Blue Jays and the father of the future Yankees catcher of the same name – offered Sierra $15,000 to sign with the team. But when Sierra asked for more, legendary Blue Jays scout Epy Guerrero balked at the price.

After working out for Rangers scout Orlando Gomez, Sierra signed with Texas for a reported $30,000 on Nov. 21, 1982.

Sierra debuted as a professional with the Rangers’ Gulf Coast League team in 1983, hitting .242 in 48 games and launching his career as a switch-hitter. A natural right-handed batter, Sierra was encouraged to switch-hit by minor league coach Rudy Jaramillo, who went on to serve as the Rangers’ hitting coach for 15 seasons.

By the spring of 1984, Rangers farm director Tom Grieve was already touting Sierra as a possible big league star. He moved up to Class A Burlington of the Midwest League that season, hitting .264 with 33 doubles, 75 RBI and 13 steals in 1983.

Then in 1985, Sierra hit .253 with 34 doubles, 13 homers, 74 RBI and 22 steals for Double-A Tulsa of the Texas League. After 46 games in 1986 with Triple-A Oklahoma City – where he was leading the American Association with nine home runs and 41 RBI – Sierra was brought up to the big leagues.

“I’m not a soothsayer, so I don’t know what evil lurks beyond this night,” Rangers manager Bobby Valentine told the Star-Telegram. “I’ll just say that I think Rubén has the talent to play in the major leagues. Even if it’s a short-lived stay for Rubén, I think it’s going to help him in the future and help us right now.”

The stay turned out to be permanent, as Sierra would not appear in another minor league game for more than a decade.

Sierra debuted on June 1 against the Royals in Kansas City, going 2-for-3 with a double, home run, walk and three RBI. He would start regularly the rest of the season in all three outfield spots, finishing the year with a .264 batting average, 13 doubles, 10 triples (setting a new Texas Rangers team record), 16 homers and 55 RBI in 113 games. He finished sixth in the AL Rookie of the Year balloting.

Then in 1987, Sierra hit .263 with 35 doubles, 30 homers, 109 RBI and 16 steals. He became just the sixth player in history to tally a 30 home run/100 RBI season before turning 22, joining Jimmie Foxx, Mel Ott, Hal Trosky, Ted Williams and Eddie Mathews.

Sierra accomplished all that despite a 6-for-48 slump (.125 batting average) to end the season.

“He’s as good a talent as I’ve seen – at any age,” Rangers first baseman Tom Paciorek told the Star-Telegram. “He can do so much. He might at one point hit 40 home runs and steal 30 bases.”

Sierra finished 20th in the American League Most Valuable Player voting that season, providing him with some welcome publicity. But the next time he received MVP votes would not be as pleasant.

In 1988, Sierra hit .254 with 23 homers, 91 RBI and 18 steals. Then in 1989, Sierra put it all together by hitting .306 with 35 doubles, 101 runs scored and 29 home runs to go along with league-best totals in triples (14), RBI (119), slugging percentage (.543) and total bases (344). Those totals came despite Sierra’s concern about the devastation of Hurricane Hugo – which destroyed the homes of Sierra’s mother and grandmother in Puerto Rico – weighing on his mind.

“If he stays healthy,” Valentine told the Star-Telegram, “he’s a Hall of Famer.”

Sierra earned a starting berth in the All-Star Game and a Silver Slugger Award for his play in right field in 1989. But when the MVP voting was announced, Sierra was 28 points behind Milwaukee’s Robin Yount, who got eight first-place votes compared to six for Sierra.

Modern metrics – a season Wins Above Replacement total of 5.8 for Yount and 5.9 for Sierra – are virtually even. But Sierra believed the award should have been his.

“I don’t just want to be a good player, I want to be the best,” Sierra told the Star-Telegram. “The Hall of Fame – that’s where I want to be. I want to be one of the greatest players ever.”

Sierra got a raise of more than $1.3 million for the 1990 season and spent some of it on a car collection that included a Lamborghini, a Ferrari and a Mercedes. But the Rangers were hesitant to commit to Sierra long-term, setting in motion events that would eventually lead to a trade that rocked the game.

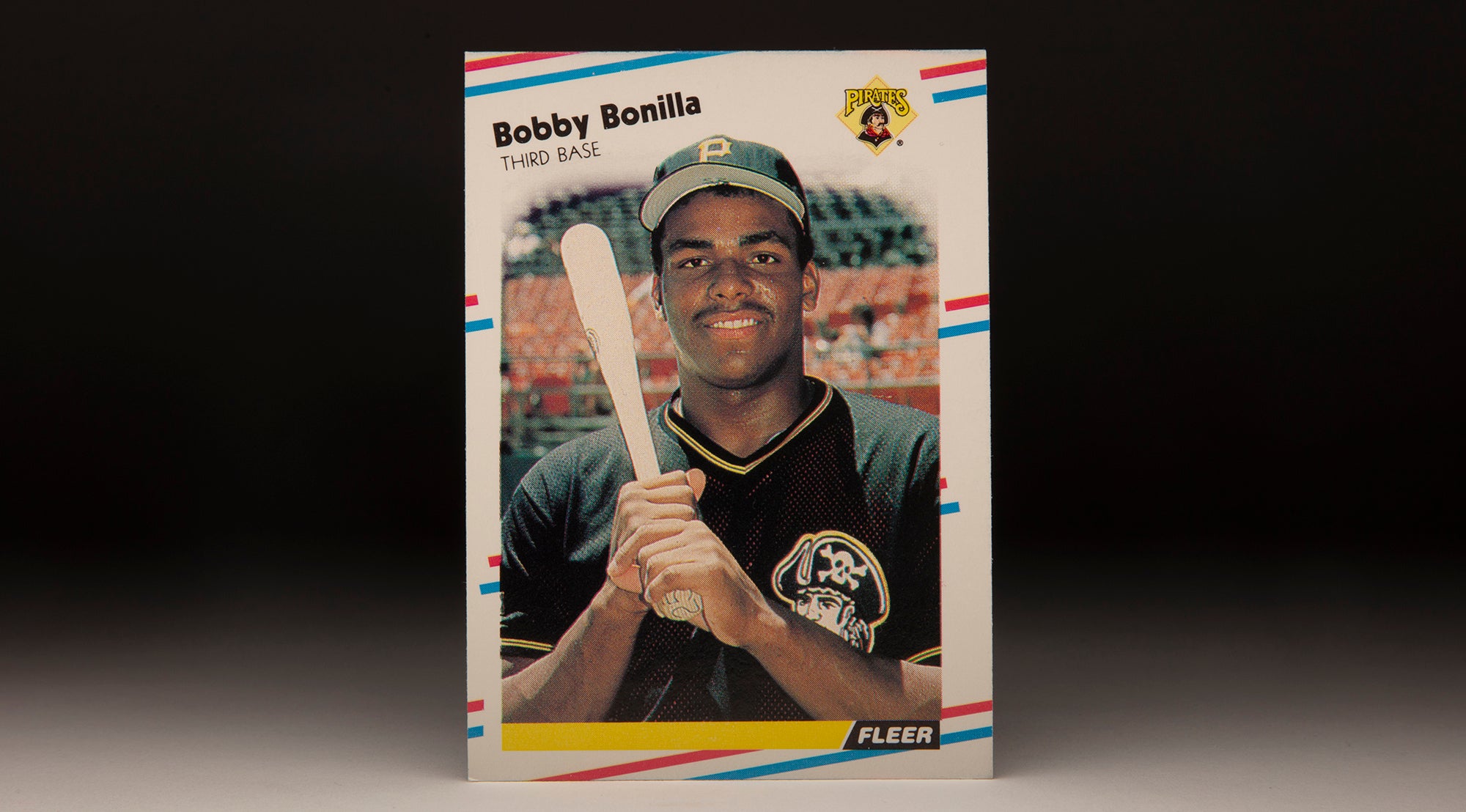

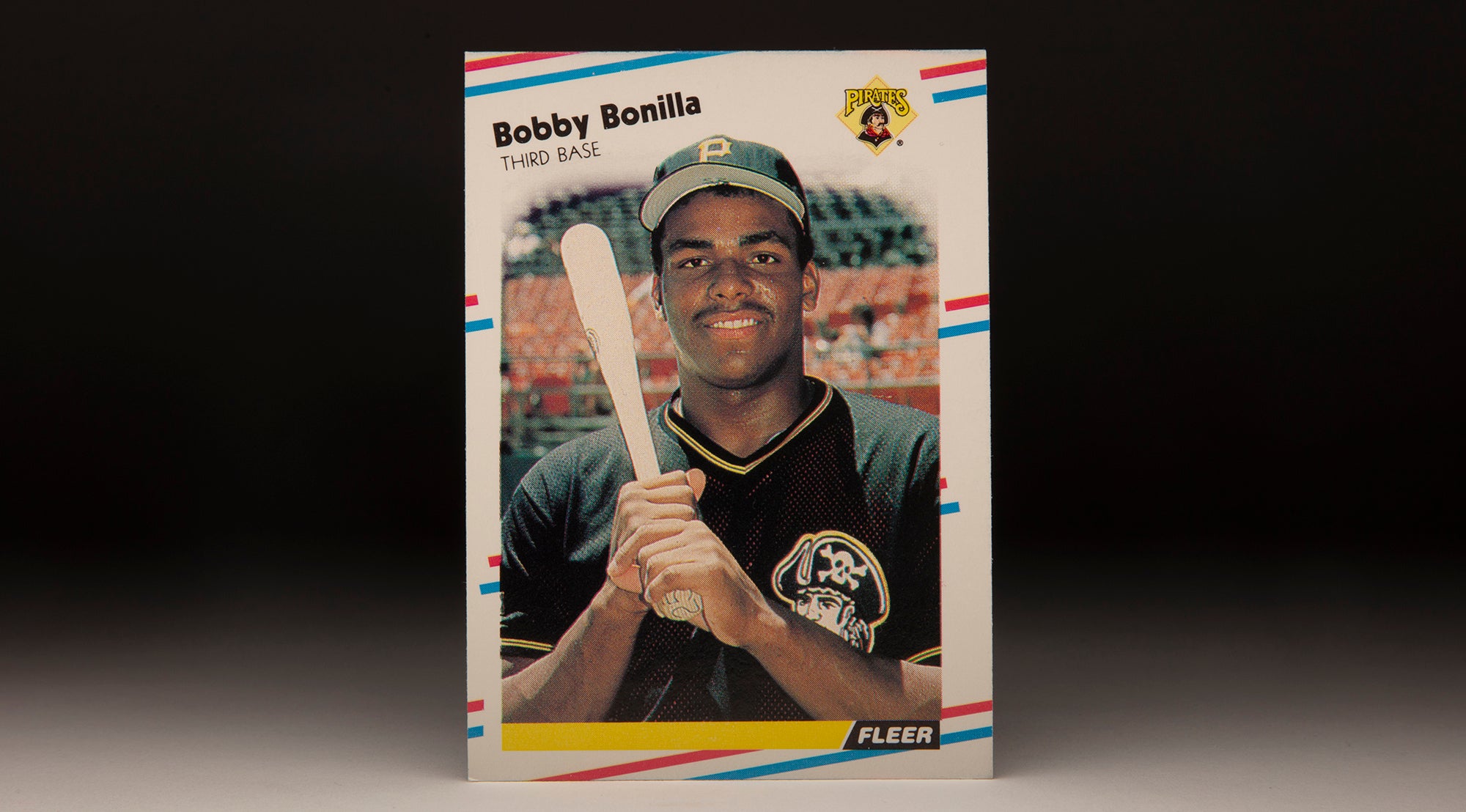

Sierra was not as productive in 1990 but still hit .280 with 16 homers, 37 doubles and 96 RBI while setting a Rangers record by playing in 325 straight games. Then in 1991, Sierra virtually duplicated his 1989 season by hitting .307 with 110 runs scored, 44 doubles, 25 homers, 116 RBI, 16 steals and 332 total bases. But with free agency looming, Sierra and the Rangers could not agree on a long-term deal – with Sierra asking for $31 million over five years, $2 million more than the record deal Bobby Bonilla had signed with the Mets a month earlier. The Rangers reportedly offered five years and $23 million.

Sierra then asked for $5 million in arbitration for the 1992 season – the Rangers offered $3.8 million – and won his case, giving him the second-largest salary in the AL that year.

“There’s a very limited market for that kind of player, with his contract situation and what a team would have to give up,” Rangers general manager Tom Grieve told Cox News Service in the winter of 1992 about potentially trading Sierra. “More likely a trade could come in August, July or September if we’re not winning. But that’s unlikely because I think we’ll be winning, hopefully with Rubén in the first year of a multiyear deal.”

But when Sierra’s numbers regressed to his 1990 levels – and the Rangers hovered close to .500 – Grieve decided a trade was necessary. On Aug. 31, 1992, the Rangers shipped Sierra, Jeff Russell and Bobby Witt to the Athletics in exchange for José Canseco. It was a deal that virtually no one could have fathomed just three years earlier when Sierra was a 23-year-old runner-up in the MVP race and Canseco was leading the Athletics to the World Series title.

“He wants the fans to appreciate him,” Rangers first baseman Rafael Palmeiro told the Modesto Bee after Sierra was traded to Oakland. “And it got to the point where they didn’t. He was hurt. He really was. He’s the kind who keeps a lot of the hurt and pain inside. He’s always been that way.”

Sierra hit .277 with three home runs and 17 RBI in 27 games for the A’s in the last month of the season, helping Oakland win the American League West title. He had eight hits in 24 at-bats (batting .333) with two doubles, a triple, a homer and seven RBI in six games as the A’s lost to Toronto in the ALCS.

On Dec. 21, 1992, Sierra got the contract he was looking for when he re-signed with the Athletics for $30 million over five seasons. He reported to Spring Training in 1993 with 20 pounds of muscle added to his frame.

“I want to see if I can take more balls out of the yard,” Sierra told the Associated Press. “I knew (Oakland) wanted to sign me. They treated me nicely and I like the club. I want to go hard and have a good year for the next five years.”

But Sierra’s time in Oakland would be brief. He was productive in 1993 with 22 home runs, 101 RBI and 25 steals but hit just .233, drawing criticism during an era where batting average was still a major yardstick for players. He bounced back with 23 homers, 92 RBI and a .268 batting average in 110 games in the strike-shortened 1994 season.

But he often clashed with manager Tony La Russa, and on July 28, 1995, the A’s sent Sierra to the Yankees with Jason Beverlin in exchange for Danny Tartabull.

“(The fans in New York) have received me like I never believed they were going to receive me,” Sierra told the San Francisco Examiner after about a month with the Yankees. “Like they never received me here in Oakland. I don’t have to be the bad guy anymore.”

Sierra drove in 44 runs over 56 games with the Yankees, helping New York advance to the postseason for the first time since 1981. He finished the season with a .263 batting average, 19 homers and 86 RBI in 126 games – then hit two home runs in the Yankees’ ALDS vs. the Mariners. But both of his home runs came in New York’s wins in Games 1 and 2 – and in the final three games Sierra was a combined 1-for-11 (.091) as Seattle rallied to win the series.

In 1996, Joe Torre replaced Buck Showalter as the Yankees manager. Sierra was the rare player who did not get along with Torre, and on July 31 – with Sierra hitting .258 with 11 home runs and 52 RBI in 96 games – the Yankees traded him to the Tigers in a deal for Cecil Fielder. It turned out to be a trade that powered New York to the World Series title as Fielder had a memorable postseason.

Sierra, meanwhile, finished the year with 12 homers and 72 RBI in 142 games. He was quoted in the media upon leaving New York as saying: “The only thing this organization cares about is winning.”

Entering the final season of his five-year deal, Sierra was traded to the Reds for two minor leaguers on Oct. 28, 1996. He appeared in only 25 games before Cincinnati released him on May 9, seemingly putting his career at a crossroads.

But the Blue Jays signed him two days later and sent him to Triple-A Syracuse before recalling him in late May. He hit just .208 in 14 games, however, drawing his release once again.

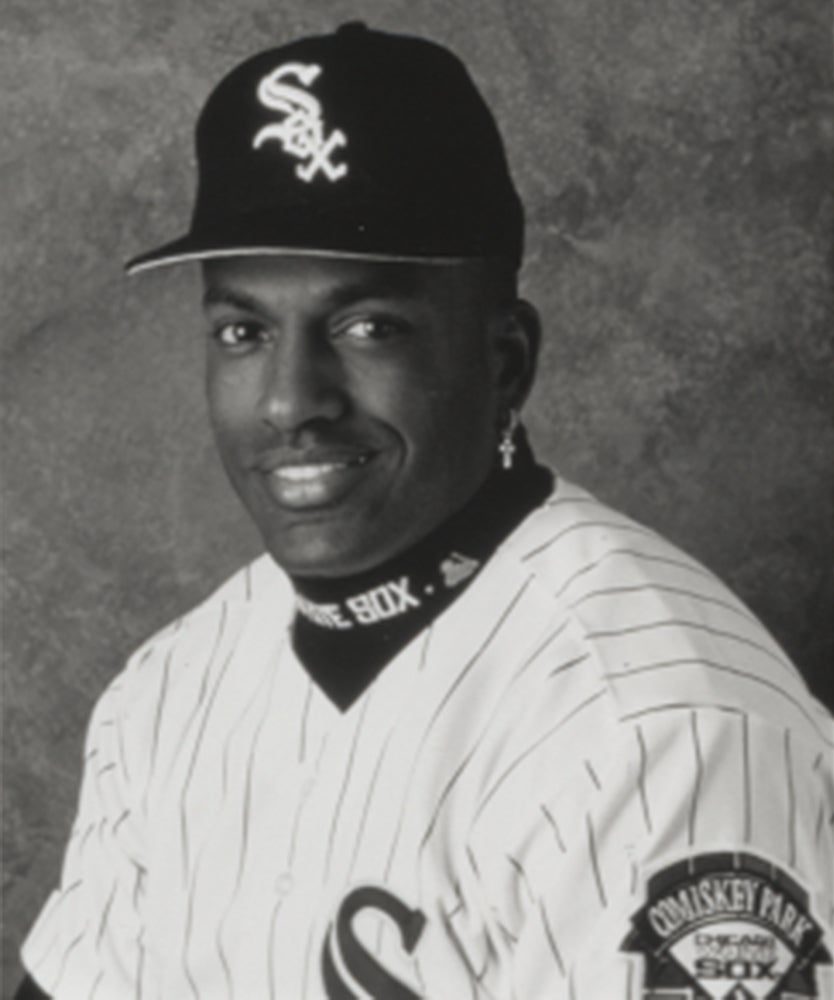

Sierra hooked on with the White Sox at the start of the 1998 season, hit .216 in 27 games and was released again. He signed with the Mets but never got out of Triple-A. Then in 1999, Sierra signed with the Atlantic City Surf of the independent Atlantic League. He refurbished his career by hitting .294 with 28 homers and 82 RBI in 112 games, earning a contract with Cleveland for the 2000 season.

“Of all the major leaguers we had – José Canseco, Pete Incaviglia and others – Rubén was the best when it came to helping young players or helping sell baseball to our new franchises,” Atlantic League president Joe Klein told the Toronto Sun.

Cleveland released Sierra at the end of Spring Training, and he went to the Mexican League before the Rangers brought him back on a minor league deal. After hitting .326 with 18 homers and 82 RBI in 112 games for Triple-A Oklahoma City, Sierra joined the Rangers in September.

“This is a blessing,” Sierra told the Star-Telegram as he hugged old friends, including Rudy Jaramillo. “I’m very happy to be here. I want to say thank you to the Rangers and thank God for bringing me back.”

Sierra hit just one home run in 20 games in September and was released after the season before returning on a minor league deal. It turned out to be a good decision for the Rangers as Sierra batted .291 with 23 homers and 67 RBI in 94 games in 2001.

Sierra signed with the Mariners for the 2002 season and played in 122 games that year, hitting 13 home runs and driving in 60 runs while batting .270.

“Right now, I feel like I’m 22 years old,” Sierra told the Toronto Sun in May of 2002 when he was leading the American League with a .358 batting average.

He returned to Texas in 2003 and was performing well off the bench when the Yankees reunited him with manager Joe Torre, trading Marcus Thames to Texas for Sierra on June 6, 2003.

“Rubén has done a good job for us, no question,” Torre told Newsday one week after he was reacquired by New York as Sierra went three for his first seven at the plate.

Sierra hit .276 in 63 games off the bench for New York that year, then added a pinch-hit home run in Game 4 of the ALCS vs. Boston and a pinch-hit, two-run triple against the Marlins in Game 4 of the World Series which sent the contest into extra innings.

Sierra returned to the Yankees in 2004 and played in 107 games, hitting 17 homers and driving in 65 runs. In the ALDS vs. Minnesota, Sierra’s three-run home run in the eighth inning of Game 4 tied the game at five, and New York went on to win the game in 11 innings to clinch the series. Sierra then hit .333 in the ALCS against Boston, appearing in five games as the Red Sox rallied from a three-games-to-zero deficit to advance to the World Series.

Entering his age-39 season in 2005, Sierra suffered a torn right biceps and strained left rib cage muscle after nine games, sidelining him until late May. He hit just .229 over 61 games and then pinch-hit three times against the Angels in the ALDS as the Yankees were eliminated in five games.

Sierra moved on to Minnesota in 2006, appearing in 14 games before being released on July 10. It would mark the final chapter of his big league career.

Sierra finished his 20 seasons in the big leagues with a .268 batting average, 2,152 hits, 428 doubles, 306 home runs, 142 steals and 1,322 RBI. Only eight Puerto Rican-born players have more hits, only five have more home runs and only five have more RBI. Among his countrymen, only Carlos Beltrán, Orlando Cepeda and Iván Rodríguez had a career with at least 2,000 hits, 300 home runs, 1,300 RBI and 100 steals.

Sierra’s relationships with his teammates, managers and the media were rarely smooth during his career. But despite a language barrier that often left him quiet around reporters, Sierra’s career stacks up well against almost any player of his generation.

“(Teams) used to be concerned about you as an individual,” Sierra told the Toronto Star in 1997. “Now, when you’re hurt, they don’t care about you as a human being.

“Maybe it’s a case where (I) didn’t say the words right. I play to win. I don’t like to lose.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

RELATED STORIES

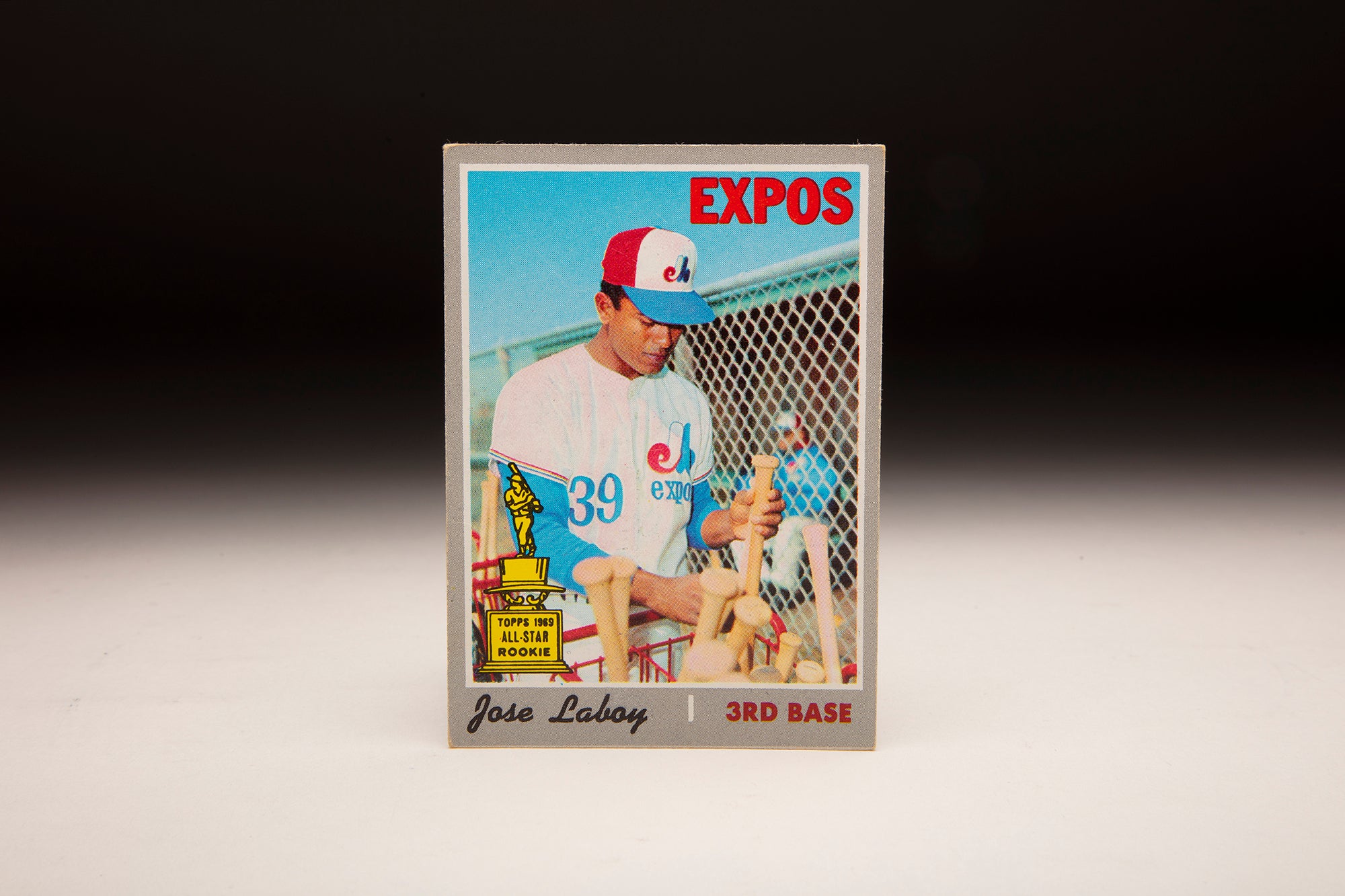

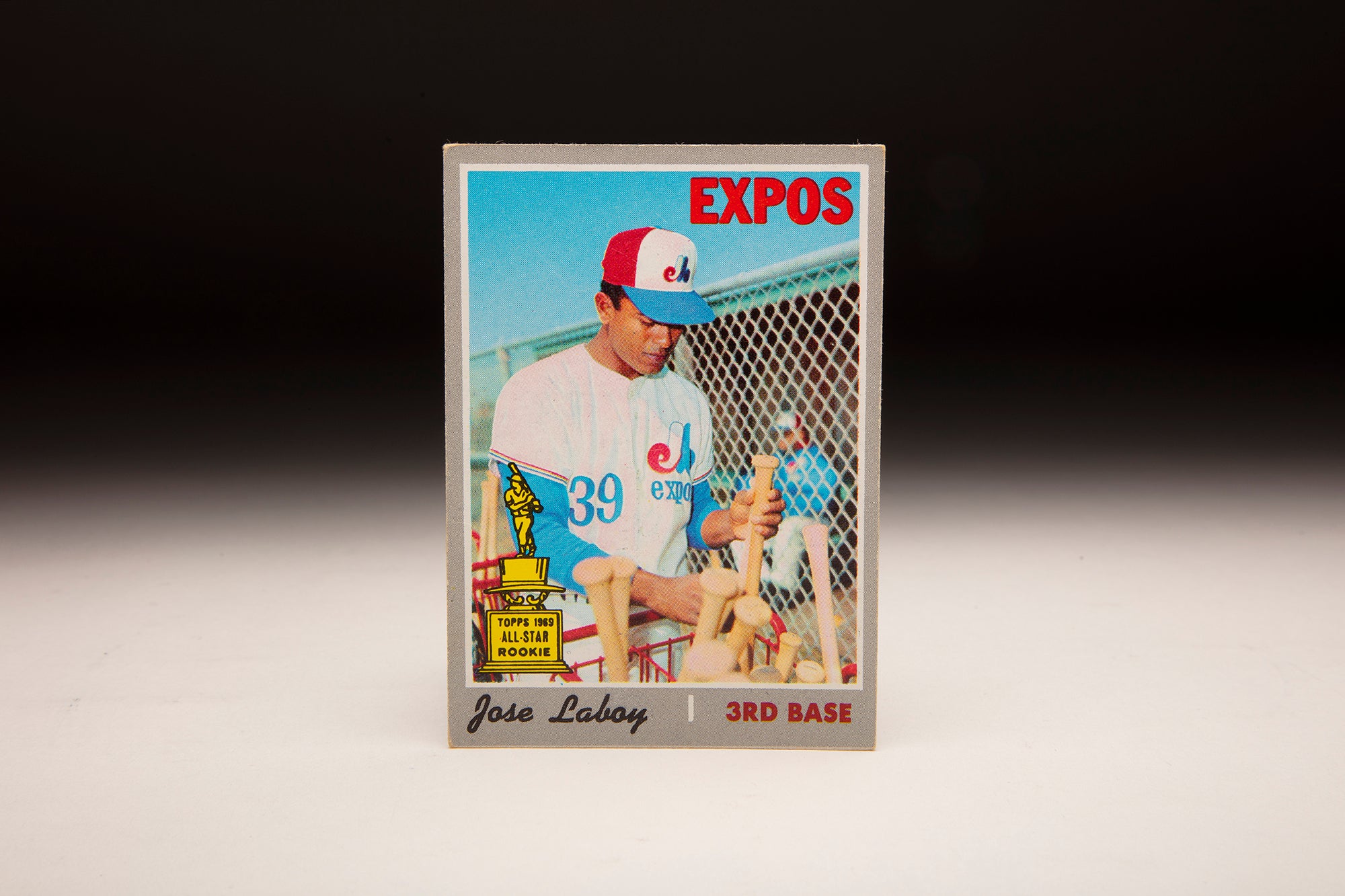

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Jose ‘Coco’ Laboy

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Juan Beníquez

#CardCorner: 1988 Fleer Bobby Bonilla

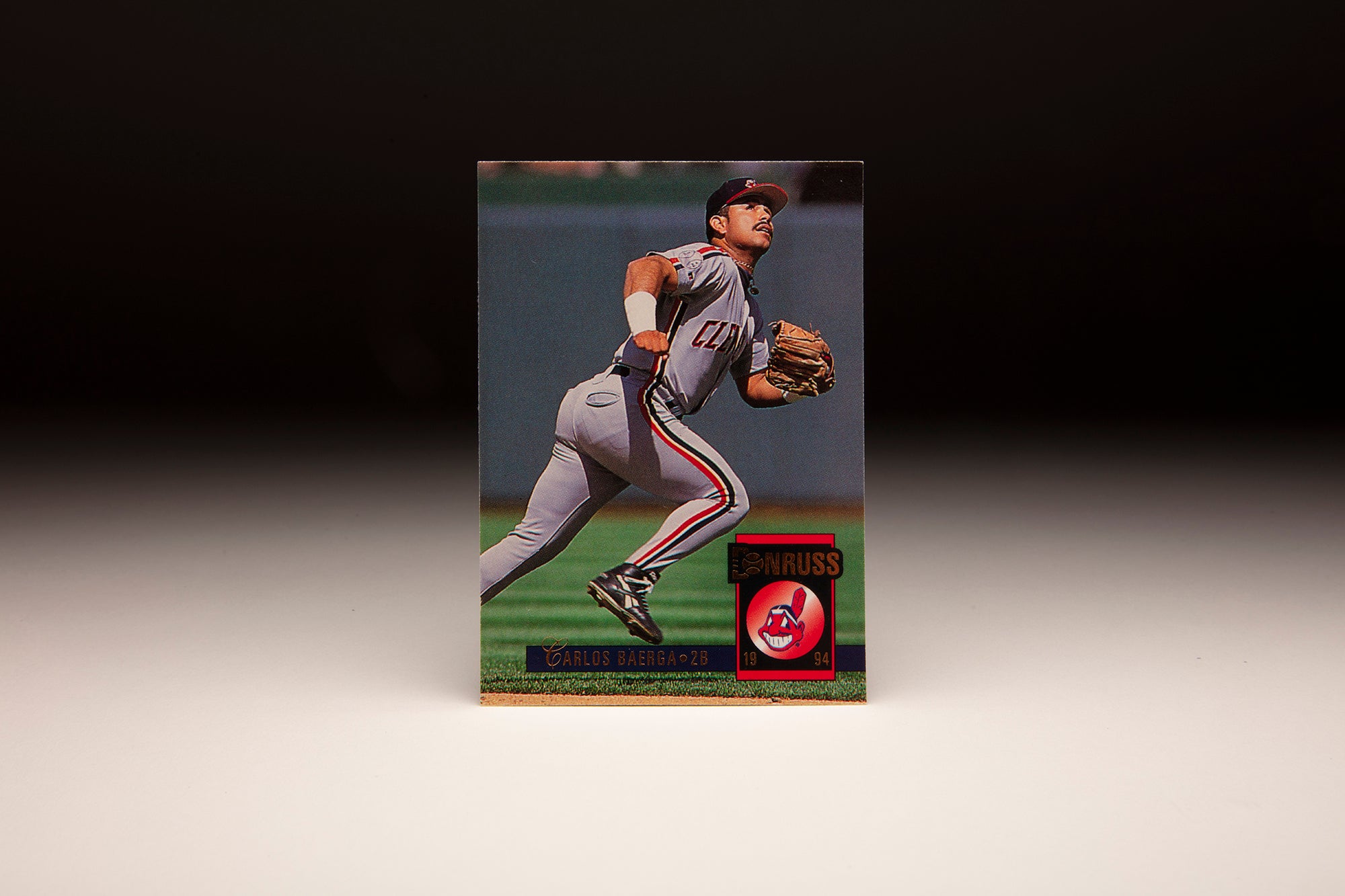

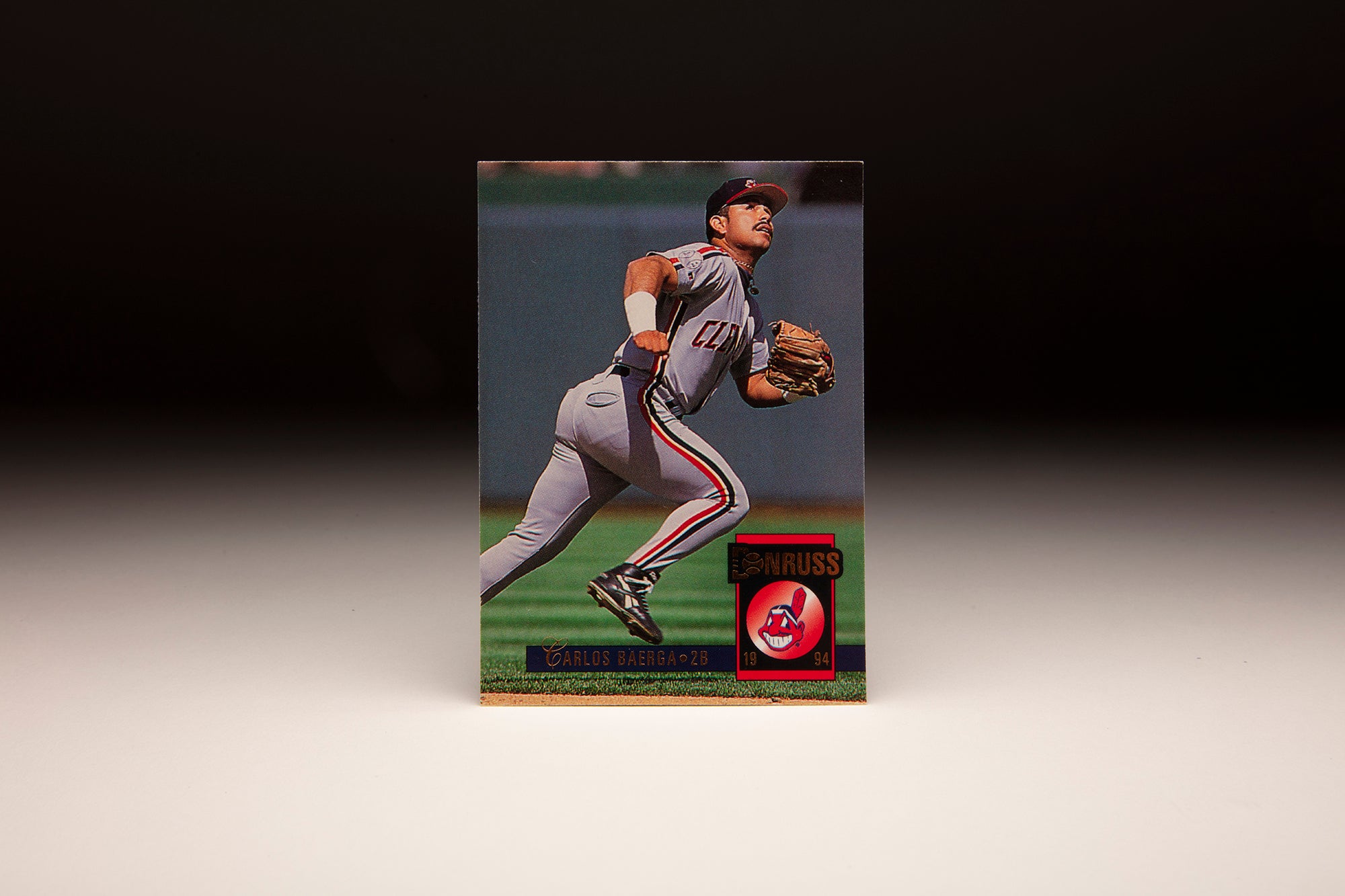

#CardCorner: 1994 Donruss Carlos Baerga

RELATED STORIES

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Jose ‘Coco’ Laboy

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Juan Beníquez

#CardCorner: 1988 Fleer Bobby Bonilla